Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Epilogue

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

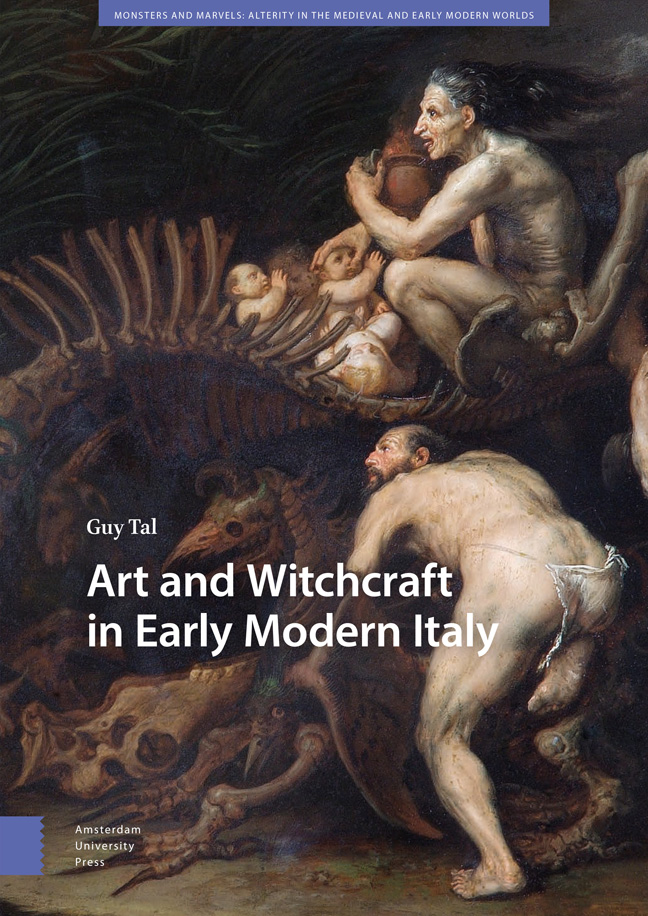

The witchcraft scenes produced by Salvator Rosa (1615–73) typically depict vibrant, bustling compositions, figuring exuberant witches performing various acts of magic. In one small canvas, however, Rosa, dispensing with eventful phenomena, chose to portray a single subdued witch kept company on a separate canvas by a soldier in full armor and martial garb in a similarly somber setting (figs. 107 and 108). These twinned pendants, sheltering today in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, were most likely produced around 1655, when Rosa lived in Rome. The witch and the soldier are each seated on a rocky ledge against a nocturnal, desolate alp hinting at a mountainside. The witch is naked from the waist up, her desiccated breasts contrasting oddly with her otherwise muscular physique. Her feet, resting on a scrap of paper inscribed with magical runes, are ringed around by lit candles. For his part, the soldier, seated on his rocky perch with his standard askew by his side, directs a melancholy look at the viewer. Residing in different planes and failing of interaction, the two figures remain physically and mentally isolated. Yet Rosa's configuration of a concatenated pair of paintings signals that the two figures, despite taking up separate residences, assume full resonance only in conjunction with one another. How, then, is this mutually enhancing yet physically discrete effect to be analyzed?

The pendant pictorial format played a vital instructive role in challenging the viewer to tease out connections between companion pieces, thus shaping and adding complexity to the viewer's aesthetic appreciation. Alive to the artistic strategies entailed by the pendant format, Rosa demonstrated his ingenuity in setting up analogies and antitheses, both compositional and iconographic, in the nearly twenty pairs of pendants dealing with a wide range of subjects. Possibilities for interpretation abound. The witch and the soldier might be drawn into a closer communion by some fitting narrative, either an idiosyncratic storytelling concocted by the viewer to satisfy the requirements of coherence, or one with classical antecedents, seeming to capture the intended visual collocation as a flow of events with mythical resonance. It is amply possible to imagine a cause-and-effect scenario, even of the simplest kind, involving a witch casting a spell on the soldier at several removes. John Callow, for example, writes that the “dramatic meaning [of the pendants] is clear.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Art and Witchcraft in Early Modern Italy , pp. 317 - 326Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023