Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

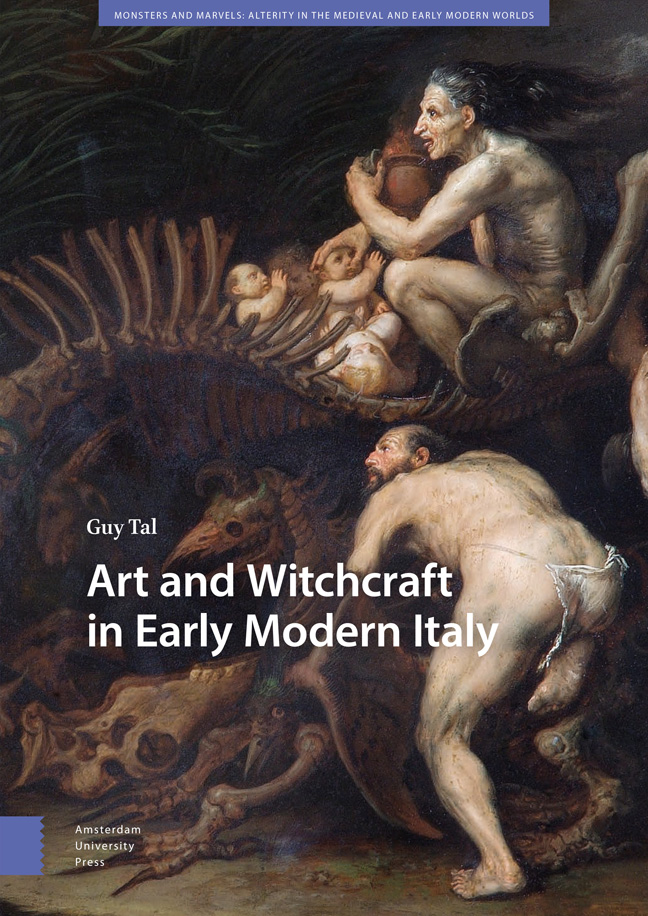

Witchcraft would seem an unexpected—even aberrant—subject matter for modern spectators to find within the rich artistic repertoire of Renaissance and Baroque Italy. How could the image of a loathsome old witch mired in necromantic depravity amidst a bevy of demonic creatures pertain to such a luminous cultural epoch, known best for intellectual prosperity, classical decorum, and ideal beauty? Art and Witchcraft in Early Modern Italy seeks to explore the diverse ways in which Italian artists responded to and engaged with the early modern idea of witchcraft. The artworks examined throughout this book relate to such aberrational topics as diabolical worship, infanticide, skull necromancy, nightmares, delusions, psychopathology, hybridity, metamorphosis, and arrant sexual deviancy. Far from presenting witchcraft as an iconographical non sequitur in the artistic canon or as evidence of a latent “Anti-Renaissance,” this book sets out to show that witchy frescoes, paintings, prints, and drawings comported with—and indeed bore out the values of—the milieu's artistic, cultural, and intellectual climate.

Witchcraft is a subject matter that foregrounds the traditional bifurcated split in early modern Europe between Northern and Italian art. Against the ample stock of Northern scenes of witchcraft produced by Hans Baldung Grien, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Jacques de Gheyn II, David Teniers II, and scores of other German, Dutch, and Flemish artists, the Italian record is significantly slimmer. Equally, pamphlets, broadsheets, and book illustrations propagating the details of witches’ deeds and executions across Northern Europe went unprinted in Italy excepting one illustrated treatise. It should be unsurprising, then, that the vast majority of scholarly publications and exhibitions devoted to witchcraft imagery are weighted towards the study of sixteenth-century German and seventeenth-century Flemish and Dutch images, whose depictions predominate this iconographic niche.

It was not until 1962 that early modern Italian images of witchcraft emerged as a subject of scholarly enquiry. This was when Eugenio Battisti included the chapter “Nascita della strega” (Birth of the Witch) in his pivotal L’antirinascimento alongside others on previously unsung topics (such as automata, astrology, and monstrous statues). Through this, Battisti aspired to uncover the true, untold heterogeneity of sixteenth-century Italian art. Thereafter, art historians sought to examine the subject from myriad directions. Most critical attention has, unsurprisingly, been paid to Salvator Rosa, who produced no less than twenty witchcraft paintings and drawings, significantly excelling other Italian artists working within the genre.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Art and Witchcraft in Early Modern Italy , pp. 19 - 40Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023