Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction: Seeking Perspective on a Slow-Burn Civil War

- 2 The Culture of the Army, Matichon Weekly, 28 May 2010

- 3 Thoughts on Thailand's Turmoil, 11 June 2010

- 4 Truth and Justice When Fear and Repression Remain: An Open Letter to Dr Kanit Na Nakorn, 16 July 2010

- 5 The Impact of the Red Shirt Rallies on the Thai Economy

- 6 The Socio-Economic Bases of the Red/Yellow Divide: A Statistical Analysis

- 7 The Ineffable Rightness of Conspiracy: Thailand's Democrat-ministered State and the Negation of Red Shirt Politics

- 8 A New Politics of Desire and Disintegration in Thailand

- 9 Notes towards an Understanding of Thai Liberalism

- 10 Thailand's Classless Conflict

- 11 The Grand Bargain: Making “Reconciliation” Mean Something

- 12 Changing Thailand, an Awakening of Popular Political Consciousness for Rights?

- 13 Class, Inequality, and Politics

- 14 Thailand's Rocky Path towards a Full-Fledged Democracy

- 15 The Color of Politics: Thailand's Deep Crisis of Authority

- 16 Two Cheers for Rally Politics

- 17 Thai Foreign Policy in Crisis: From Partner to Problem

- 18 Thailand in Trouble: Revolt of the Downtrodden or Conflict among Elites?

- 19 From Red to Red: An Auto-ethnography of Economic and Political Transitions in a Northeastern Thai Village

- 20 The Rich, the Powerful and the Banana Man: The United States’ Position in the Thai Crisis

- 21 The Social Bases of Autocratic Rule in Thailand

- 22 The Strategy of the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship on “Double Standards”: A Grand Gesture to History, Justice, and Accountability

- 23 No Way Forward but Back? Re-emergent Thai Falangism, Democracy, and the New “Red Shirt” Social Movement

- 24 Flying Blind

- 25 The Political Economy of Thailand's Middle-Income Peasants

- 26 Royal Succession and the Evolution of Thai Democracy

- Index

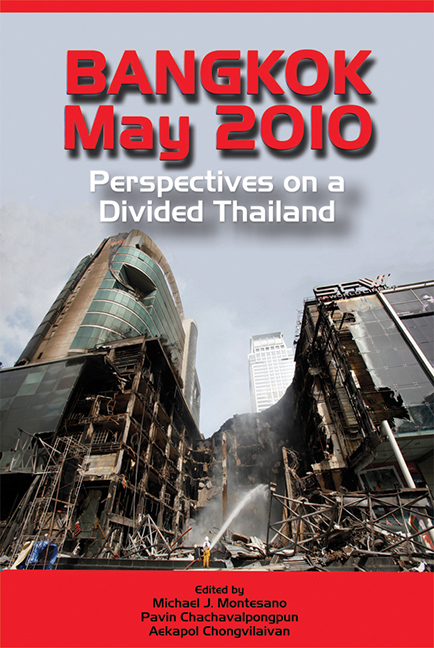

- Plate section

11 - The Grand Bargain: Making “Reconciliation” Mean Something

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction: Seeking Perspective on a Slow-Burn Civil War

- 2 The Culture of the Army, Matichon Weekly, 28 May 2010

- 3 Thoughts on Thailand's Turmoil, 11 June 2010

- 4 Truth and Justice When Fear and Repression Remain: An Open Letter to Dr Kanit Na Nakorn, 16 July 2010

- 5 The Impact of the Red Shirt Rallies on the Thai Economy

- 6 The Socio-Economic Bases of the Red/Yellow Divide: A Statistical Analysis

- 7 The Ineffable Rightness of Conspiracy: Thailand's Democrat-ministered State and the Negation of Red Shirt Politics

- 8 A New Politics of Desire and Disintegration in Thailand

- 9 Notes towards an Understanding of Thai Liberalism

- 10 Thailand's Classless Conflict

- 11 The Grand Bargain: Making “Reconciliation” Mean Something

- 12 Changing Thailand, an Awakening of Popular Political Consciousness for Rights?

- 13 Class, Inequality, and Politics

- 14 Thailand's Rocky Path towards a Full-Fledged Democracy

- 15 The Color of Politics: Thailand's Deep Crisis of Authority

- 16 Two Cheers for Rally Politics

- 17 Thai Foreign Policy in Crisis: From Partner to Problem

- 18 Thailand in Trouble: Revolt of the Downtrodden or Conflict among Elites?

- 19 From Red to Red: An Auto-ethnography of Economic and Political Transitions in a Northeastern Thai Village

- 20 The Rich, the Powerful and the Banana Man: The United States’ Position in the Thai Crisis

- 21 The Social Bases of Autocratic Rule in Thailand

- 22 The Strategy of the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship on “Double Standards”: A Grand Gesture to History, Justice, and Accountability

- 23 No Way Forward but Back? Re-emergent Thai Falangism, Democracy, and the New “Red Shirt” Social Movement

- 24 Flying Blind

- 25 The Political Economy of Thailand's Middle-Income Peasants

- 26 Royal Succession and the Evolution of Thai Democracy

- Index

- Plate section

Summary

Not five decades ago, political scientist David Wilson described Thai society in terms that offer a window into the socio-economic roots of the political crisis that has enveloped the country since 2006. Back then, Wilson observed “a clear distinction between those who are involved in politics and those who are not” — adding that “the overwhelming majority of the adult population is not.” He went on to say:

The peasantry as the basic productive force constitutes more than 80 percent of the population and is the foundation of the social structure. But its inarticulate acquiescence to the central government and indifference to national politics are fundamental to the political system. A tolerable economic situation which provides a stable subsistence without encouraging any great hope for quick improvement is no doubt the background of this political inaction.

Writing on the heels of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat's 1958 conservative revolution, David Wilson was correct to identify in the “acquiescence” and “indifference” of the vast majority of the public the fundamental basis of “Thai-Style Democracy” — a system of government that, notwithstanding the appropriation of some of the trappings of democracy, has since largely preserved the right of men of high birth, status, education, and wealth to run the country.

Indeed, it was in the interest of building this system of government that Sarit had insisted that the rural population be forever content to eke out a simple existence upcountry — the refusal of many to embrace their station in life portending the “deterioration” of Thai society. It was in the interest of preserving this system of government that the Thai people have more recently been urged to walk “backwards into a khlong” and renounce progress in favour of a simpler existence. And it was in the interest of reiterating what this system of government once expected of them that Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva promised in March 2010 that everything will be fine in Thailand, so long as the Thai people continue to “do their jobs lawfully”. In a “Sufficiency Democracy”, as Andrew Walker calls it, a good citizen is not just satisfied with whatever life has given him; equally important, he accepts a political role commensurate to the size of his barami.

“Thai-Style Democracy” was not destroyed in one day.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Bangkok, May 2010Perspectives on a Divided Thailand, pp. 120 - 130Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2012