Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Chronology

- I Ermita and Santa Cruz to Intramuros: Between Literary and Legal Career

- II To Tokyo and Back: The Making of a Diplomat

- 5 The Assistant Solicitor

- 6 From Intelligence Officer in Bataan to the Return of Ignacio Javier

- 7 Second, then First Secretary

- 8 At the Home Office: The Diplomat as Historian

- III Going In, then Out of the Political Jungle: Padre Burgos to Arlegui

- IV London and Madrid: The Philippines in a Resurgent Asia

- V New Delhi to Belgrade: The Philippines towards Non-Alignment

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- List of Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

6 - From Intelligence Officer in Bataan to the Return of Ignacio Javier

from II - To Tokyo and Back: The Making of a Diplomat

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Chronology

- I Ermita and Santa Cruz to Intramuros: Between Literary and Legal Career

- II To Tokyo and Back: The Making of a Diplomat

- 5 The Assistant Solicitor

- 6 From Intelligence Officer in Bataan to the Return of Ignacio Javier

- 7 Second, then First Secretary

- 8 At the Home Office: The Diplomat as Historian

- III Going In, then Out of the Political Jungle: Padre Burgos to Arlegui

- IV London and Madrid: The Philippines in a Resurgent Asia

- V New Delhi to Belgrade: The Philippines towards Non-Alignment

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- List of Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Summary

Guerrero did not believe that Japan would attack the Philippines because it would mean engaging the United States. Still, the radio commentator known as Ignacio Javier was critical of Japanese aggression starting in Manchuria in 1931, China in 1937 and northern Indochina in 1940. After Pearl Harbour was attacked on 8 December 1941, he was even more relentless in his denunciation of the Japanese along with Salvador “SP” Lopez, a fellow newsman. They belonged to a group of broadcast and print journalists who saw Japan as a threat; they would be loosely called “Japanophobes” along with others of similar persuasion.

His career as a solicitor was cut short the next day after the Pearl Harbour bombing and the almost simultaneous bombings on Clark Field, Baguio and Davao, putting employees of the courts and other offices in the bureaucracy in a state of panic. A few days before Manila fell however, he was still broadcasting over the air. Then, upon the advice of the Jesuit Superior, Father John F. Hurley, SJ, who told them that “the Japs will make mince meat of the two of you if they find you here” and the Jesuits’ help in securing a transport through the assistance of Mr Chick Parsons, he and Lopez fled from the burning city by clinging to the deck of a Luzon Stevedoring barge with anti-aircraft guns. It was the night of New Year's Day. The barge kept on circling the bay throughout the night until it brought them to Bataan. Americans arrested them for they suspected them to be Japanese spies. Fortunately Major Carlos P. Romulo of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) Public Relations in a visit to Bataan recognized the two familiar faces from his Herald days and got them released and commissioned. Since the Americans needed only one Filipino propaganda officer in Corregidor, Lopez who had a boil went with Romulo while Guerrero stayed in Bataan.

FROM MIS TO THE VOICE OF FREEDOM

In Bataan, Guerrero was assigned to the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) unit with the rank of first lieutenant under Brigadier General Simeon de Jesus. He did not know that in Manila the Japanese, upon their arrival in January, were looking for him and Romulo for immediate execution.

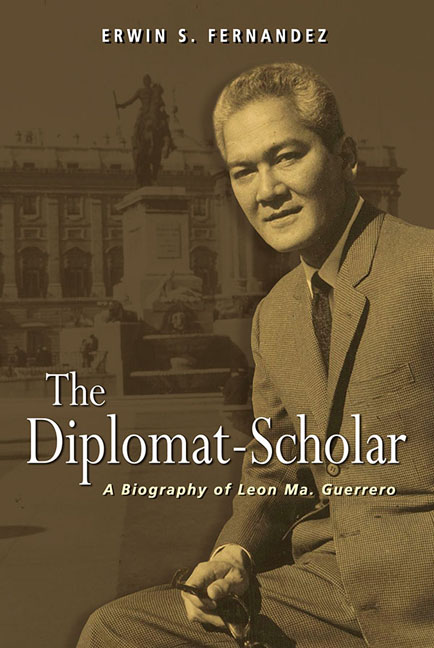

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Diplomat-ScholarA Biography of Leon Ma. Guerrero, pp. 73 - 83Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2017