Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Summary

Enter the mask

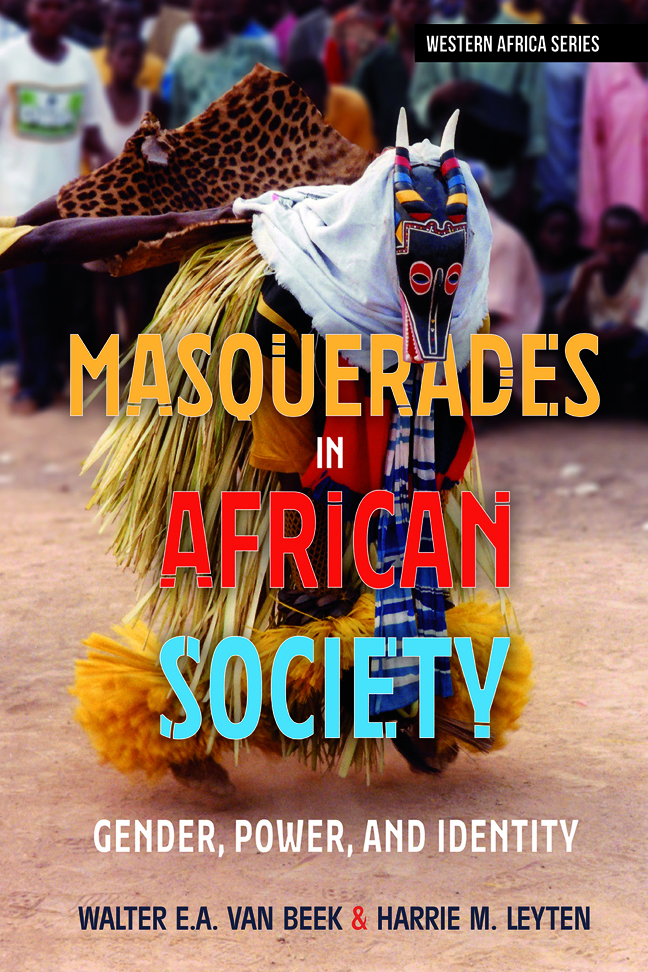

In the late afternoon the compound of Oulai Théodore is filling up with spectators eager to see the gegbadë mask, which is renowned in the Ivorian city of Man, the capital of the Dan peoples. The courtyard is lined with benches facing the raffia wall that hides the house from view, and the men, women, and children from the village gradually find their places. At sunset, three musicians move in with drums, and a singer uses a gourd rattle to set the tempo. Their first task is to call the spirits, for without their inspiration the mask cannot work. The audience appreciates this as well, clapping and singing along while they start to dance; in Africa music means movement. A small chorus of young men and girls gathers around the singer, just next to the raffia wall, singing the response lines while dancing and clapping to the rhythm. The call for the mask is followed by the getan, the music of the mask. This music is more joyful and intense, and the dancing picks up. The atmosphere grows livelier and more animated, to prepare the audience but mainly to persuade the spirits to join the performance. At this point a voice is heard from the inside, and a woman intones the song ‘The ge has arrived’; ge is the general word for the masked figure. Gegbadë is not yet in sight, but the people can hear it respond to the singer, using a variety of voices, muffled, shrill, even screeching – an entrancing range of voices. The chorus shouts out cries of encouragement into the enclosure, and gegbadë starts directing the music with its voice, singing and speaking in proverbs, while on the outside an interpreter repeats what the mask has said in a loud voice.

Benedictions flow from the house, with all present answering ‘amina’ (amen), and while the music and the singing are going full throttle, the masked figure slowly comes out of the house. First offering a view of its large striking beak, gegbadë lingers in the opening, a tantalising half-view for the crowd, invoking in song and speech its own spirits but also those of other houses. The master drummer enters the house and, walking backwards, guides the masked apparition into the courtyard.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Masquerades in African SocietyGender, Power and Identity, pp. 1 - 8Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023