Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

7 - Other Thaipusams

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Summary

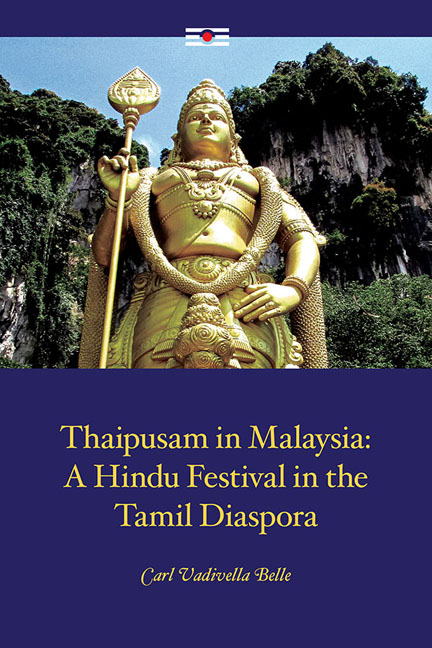

This chapter provides an overview of the commemoration of Thaipusam (or other Murugan-linked festivals) and the related incidence of kavadi worship in a variety of settings, within both metropolitan and diaspora Tamil Hindu societies. In the process it will comprehensively demonstrate that festivals of Thaipusam (or related festivals) honouring the deity Skanda-Murugan, and involving kavadi rituals, are not only widely encountered within Tamil Hindu society but in fact form a central component of the religious identity of Tamil Hindu communities, both within metropolitan India and in the broader Tamil diaspora. The cultural significance of Murugan worship and the related kavadi ritual is particularly emphasized by the examples of Fiji, where bhakti practices clearly demarcate South Indian religiosity against a backdrop of indigenous Fijian and North Indian pressures; of the Seychelles, where the recent construction of a Hindu temple and introduction of kavadi worship have fuelled a Tamil cultural and religious revival; and Medan, Indonesia, where the controversial banning of the kavadi ritual instilled a deep sense of cultural deprivation among Tamil Hindus.

In general there are several common elements found in all Murugan festivals:

A chariot procession organized by the controlling temple or religious body in which the utsava murthi is paraded and displayed to the community over which the deity exercises regnancy. (Only in two of the localities surveyed — the Seychelles and Kataragama, Sri Lanka — is the chariot ritual absent. However, as will be shown, Hindus within the Seychelles have only in recent years inaugurated the commemoration of Thaipusam as a major festival, and the community is still in the process of developing many of the key symbols of Tamil Hinduism. At Kataragama the chariot ritual is replaced by a procession involving Skanda-Murugan in the form of a yantra, that is, a mystical diagram employed to represent aspects of various deities, most commonly sakti powers, and closely identified with healing in Tamil traditions.) The chariot ceremonial is structured around the royal symbolism and kingship (in this context it should be noted that in the Brahman pada yatra described later in this chapter, members of the pilgrimage party bore all the insignia of kingship). While Murugan is typically symbolized by the Vel, his kingship at Palani, and thus in Thaipusam generally, is characterized by the danda, or staff.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Thaipusam in MalaysiaA Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora, pp. 244 - 287Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2017