Introduction

This Element focuses on eighteenth-century manuscript forms and their functions in the literary landscape of their time. Situated at the intersection of two fields, literary history and book history, the eighteenth-century manuscript, or handwritten document, has often been acknowledged in passing, but its ongoing production, circulation, and influence have only recently begun to be studied as significant phenomena in their own right.Footnote 1 One obvious reason for this neglect is the increasing dominance of the print medium as the century progressed. In particular, the emergence in the eighteenth century of widely distributed forms like the newspaper, magazine, and cheap reprint edition, as well as the development of circulating libraries and book societies, provided an opportunity for readers of modest means and in provincial settings to engage with literature, especially poetry, essays, and fiction, in print, and so that is where we tend to encounter these forms now, especially through digital facsimiles. However, often these new venues simply mirrored and amplified existing manuscript-based practices, and the arrival of cheap, mass-produced print with the invention of the steam press became a reality only after 1820. Thus, print has cast an artificially large shadow over what was in fact a well-established, lively, and accessible culture of manuscript production and circulation.

For the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, print was not only cheap, ubiquitous, and disposable: in new codex forms like the anthology, the multivolume series, and the encyclopedia, it had also become the medium of fixity and permanence, claiming to preserve the best of human thought and achievement. By contrast, from the perspective of the eighteenth-century participant in literary activities such as poetry reading and writing, the manuscript medium was the preferred way to preserve from destruction not only anti-government poetry recited in the coffeehouses or a birthday poem enclosed in a letter from a friend but also the verse account of a local scandal or a poem by Jonathan Swift that had been printed in regional newspapers.Footnote 2 That this confidence in script’s potential for longevity could be well placed is confirmed by the many surviving literary manuscripts of the period, in multiple formats and genres, from collections of culinary and medicinal “receipts” to the working notebooks of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is not to suggest that the survival record is not mixed, as will be illustrated in this Element’s Coda by the tragic fate of Phillis Wheatley’s manuscript book of poems, sought by her husband after her death and now considered irrevocably lost, in contrast with the recent unexpected recovery of her first poem in the diary of the Rev. Jeremy Belknap.

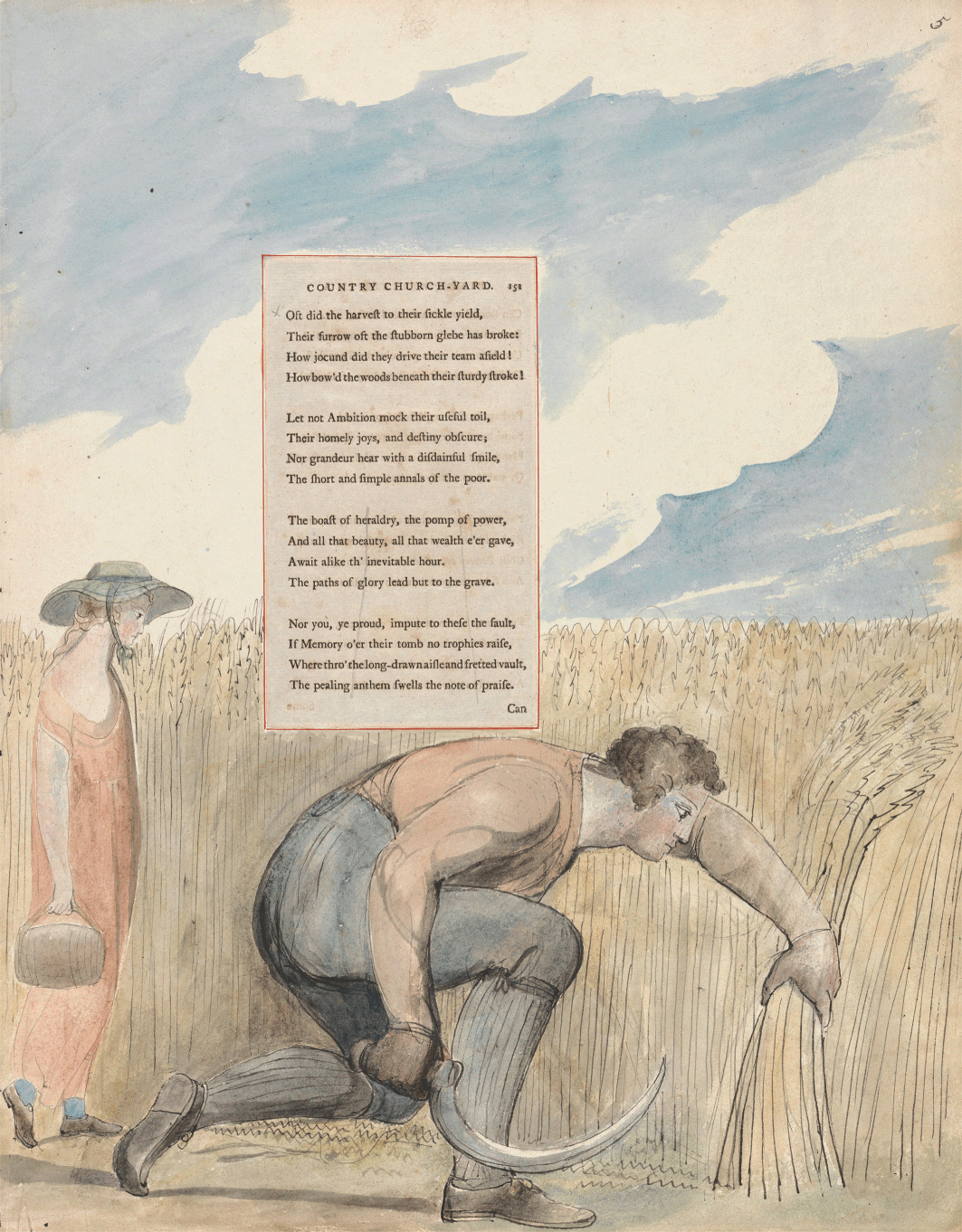

The accessibility of eighteenth-century manuscripts today is a more complicated question, as they are deposited in various archives and often available only to viewers with specialist credentials. Because all manuscripts are unique copies, they invite attention not only to survival but also to issues of remediation, that is, how they have been reproduced in different media, whether through various types of photographic reproduction or typographical representation in print editions. Even works that were printed in their own day generally come to us in remediated forms, but familiarity with the conventions of print-based remediation can blind us to the framing and potentially distorting effects of a typeset, edited, and annotated modern print edition of, for example, Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, as opposed to either the personal correspondence in which early drafts of the poem were shared or the six-penny pamphlet first published by Robert Dodsley in 1751.

As Mark Bland contends, “manuscripts are always witnesses to something other than the texts they preserve”;Footnote 3 in this Element, we are interested in the stories they have to tell about their creation, function, survival history, and ongoing importance. Above all, this Element aims to add to our growing recognition of the vigor of social and scribal modes of circulation in what has often been assumed to be the historical moment of print saturation. Looking at past centuries of print dominance, we explore a period when manuscript production was widely practiced and thriving in an interdependent relation with print – when, in fact, print had afforded new importance and variety to a range of manuscript practices.Footnote 4 We offer a guide to principal forms of literary activity carried out in handwritten manuscript forms in the eighteenth century (from the 1730s to the 1820s), beginning with an introductory section surveying the media landscape of the period from the perspective of manuscripts. The following three sections look in turn at what literary scholars can learn from three manuscript types: verse miscellanies as a distinctive manuscript genre; the familiar correspondence as an extended, collaborative text; and manuscripts of literary works that were printed early in their life cycle. These three “case study” sections are followed by a discussion of manuscript remediations from the nineteenth century to the present, focusing particularly on digital remediation. A final case study of the uneven movement of Wheatley’s poems between manuscript and print epitomizes the interpenetration of these media in the eighteenth century, as well as what manuscripts have to teach us now. While this Element has been conceived and developed as a joint endeavor, readers familiar with our work will recognize Schellenberg’s interests in the first two case studies, with the latter sections on authorial manuscripts and their remediations drawing on Levy’s expertise. Throughout this collaborative Element, we jointly aim not only to familiarize the reader with eighteenth-century manuscript culture but also to make clear the practices, challenges, and potential of manuscript study in the twenty-first century.

1 Manuscript Culture and Social Authorship in the Eighteenth Century

As noted in our introduction, manuscripts can be seen as “witnesses” to human activity, to the motivations, processes, and cultural contexts that produced them. Such an approach views the manuscript as a material object rather than simply a “text.” In the words of Jerome McGann, “documents are far from self-transparent. They are riven with the multiple histories of their own making.”Footnote 5 In addition to these histories, manuscripts also tell us about how they were used, shared, and saved. By studying manuscripts, we can learn about a range of activities first identified by Early Modern scholars as “manuscript culture” or “the manuscript system,” with characteristic practices distinct from, but still operating in tandem with, those of the world of print production.Footnote 6 Writing within this culture is sometimes described as “social authorship”:Footnote 7 manuscripts were produced, read, revised, circulated, and preserved in the context of social networks, whether held together by ties of kinship, patronage, or more egalitarian friendship – and most often, some combination of all three.

Donald H. Reiman’s threefold taxonomy of manuscripts created since the arrival of print technology is helpful here. Between the categories of private manuscript – intended for the author or only a very select few – and public manuscript – designed expressly for a large, indiscriminate, often print-based audience – lies a third category, the confidential manuscript, addressed to a social readership.Footnote 8 It is this latter category of confidential manuscript, used to create and sustain social bonds, that is central to manuscript culture in the eighteenth century. Parents wrote letters to children at school, households kept books of culinary and medical “receipts” from generation to generation; networks of women and men exchanged texts about matters ranging from religion to education to politics. Created within household libraries, schools, and clubs, literary texts were just one manuscript type among many, drafted and exchanged in notebooks and on loose sheets, sent through the postal system, copied into commonplace books and albums, and at times submitted to (or obtained clandestinely by) periodical editors or booksellers for printing in magazines or as separate pamphlets. Sometimes these works were circulated in advance of print publication; sometimes they were simply shared for enjoyment without any plan for printing them – even though a widely circulated manuscript could become “public” in its own right and would likely eventually end up in the hands of a printer.

Before moving to a description of manuscript forms, we pause to define a key term and to further explain the Element’s scope. We use the terms “publication” and “publish” to refer to print dissemination. The hand copying of texts as a commercial trade in the seventeenth century has been called “scribal publication,”Footnote 9 but the scribal profession in Britain declined considerably after 1700 (though this is less true for the American colonies and Ireland), and the copying we consider in this Element was neither centralized nor remunerated. “Publication” in this Element therefore refers to the act of publicly printing a work for distribution and, usually, sale. We confine our discussion to literary manuscripts, by which we mean manuscripts that contain recognizable literary genres – for this period, primarily poetry, fiction, and familiar letters. Although we exclude from consideration a number of genres that are not usually considered literary, such as business records and recipes, and literary forms such as drama, sermons, and essays that do not appear among our examples, this is not because any of these forms are unimportant or irrelevant to a history of the circulation of handwritten documents. Rather, we have chosen to focus on those literary genres that had significant manuscript circulation (including the travel narrative, which we will see embedded within the familiar letter) and that therefore the literary scholar will wish to take into account.

1.1 Manuscript Formats

While a unit of manuscript material – for example, a single sheet of paper with handwriting on it – may coincide with a complete “text” or “work” if that single sheet contains a complete copy, say, of Hester Chapone’s widely circulated “Ode. Occasion’d by Reading Sonnets in the Style and Manner of Spenser” and no other work, that is often not the case. A manuscript in the material sense – that single, handwritten sheet – may give physical form either to multiple texts (if it contains three or four of Chapone’s odes) or to a partial text only (if it contains only the first two stanzas of Chapone’s “Ode. Occasion’d by Reading Sonnets”). In the sections that follow, when we speak of the manuscript of a work, we will generally be discussing the complete work, such as Thomas Gray’s 1751 poem An Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard or a letter from the Bluestocking Elizabeth Montagu to her friend Anne Donnellan, whether the text is inscribed onto a folded sheet of paper (termed a manuscript “separate”) or written into a bound notebook. However, since the material state in which a manuscript work was brought into being, circulated, and preserved is often pertinent to our interpretation of its meaning and social function – its “multiple histories” – we will frequently look to its material form to guide us in studying it. Two small holes in the top corners of a letter manuscript signal that a pin was once used to bundle it together with others for subsequent reference and therefore that it was considered important in its own time. Similarly, the small size of Jane Austen’s handmade notebooks reportedly allowed her to hide her novel manuscripts when visitors entered the room. Although we attempt to distinguish clearly between these two meanings of the term “manuscript” – the handwritten version of a literary work like Frankenstein and the many notebooks filled in drafting and preparing it for printing – the reader of this study must bear the distinction in mind.

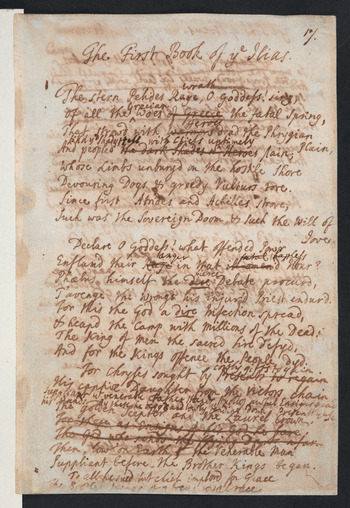

It is therefore helpful to devote some time to a preliminary discussion of manuscript formats and how these, in some cases, correlate with certain literary genres. Virtually all eighteenth-century manuscripts are made of the same material: rag paper, made from salvaged textiles. Blank writing paper could be purchased, generally from a stationer’s shop, in different formats, but most commonly as sheets of various sizes and qualities, with the finest white paper the most expensive. Although recent research has emphasized the relative affordability of single sheets of paper,Footnote 10 writers who used a great deal of it showed their awareness of its cost and what that costliness signified. The early eighteenth-century poet Alexander Pope, for example, is notorious for having drafted his translation of The Iliad on the backs of letters from his friends (Figure 1), as well as for having the prestigious and costly subscription volumes of his translation of Homer’s Iliad printed on “royal paper” (one of the largest sizes of paper for printing; 59.5 × 47 cm/23.5 × 18.5 in.) with an abundance of white space to set off the print.

Figure 1 A draft page of Alexander Pope’s manuscript of The Iliad, written on the verso of a letter to his friend John Caryll. BL MS Add. MS 4807, The British Library.

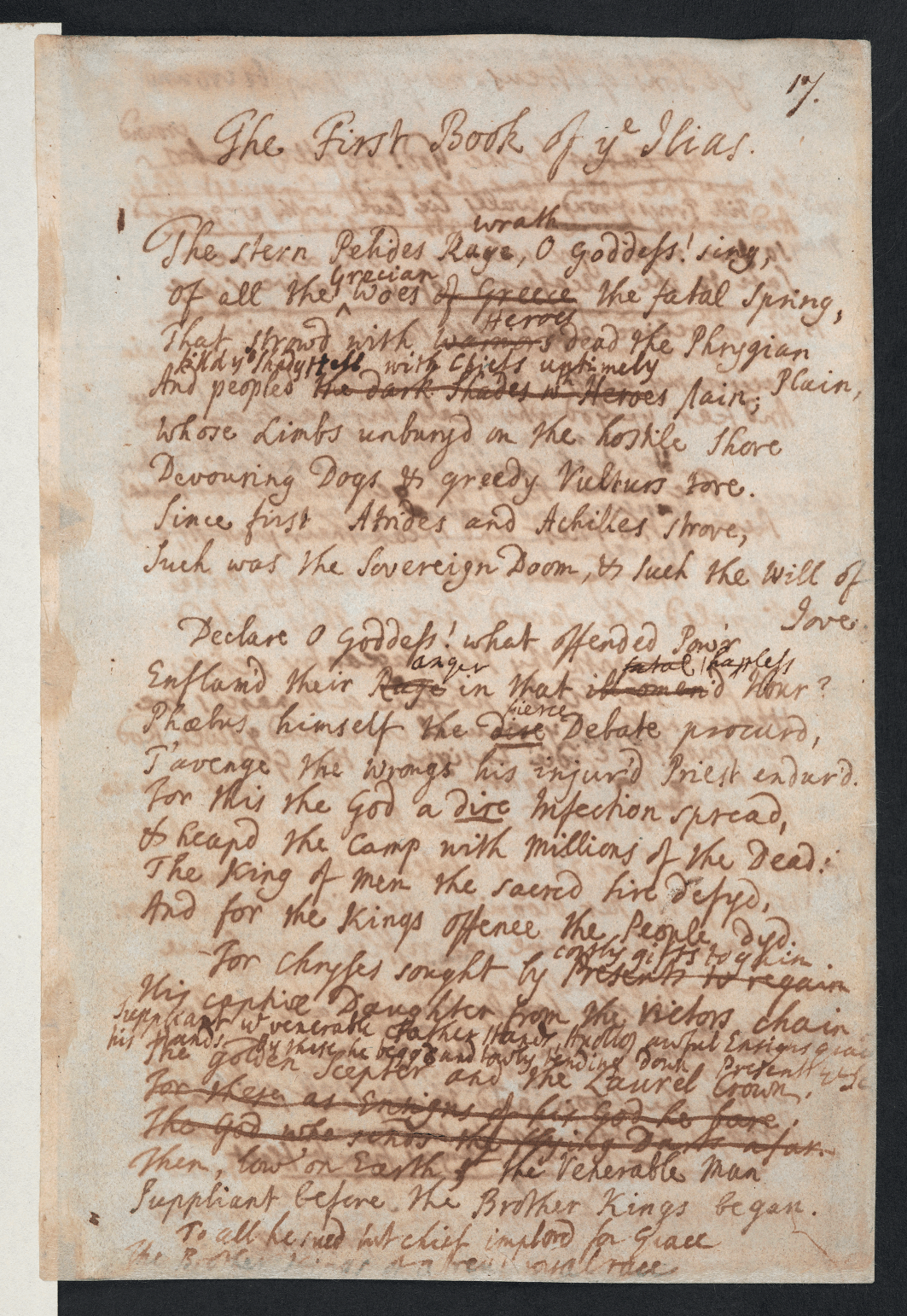

Loose sheets (also referred to as “leaves” of paper) were used for letter writing. To prepare a letter, a rectangular sheet of paper would be folded in half crosswise. This would create a two-leaf pamphlet (a bifolium), with four pages for writing. Typically, the writer would fill up to the first three pages, leaving the fourth blank or mostly blank. Folding this quarto sheet four more times created a tidy packet, which was sealed (usually with wax), leaving what remained visible of the blank fourth page to be inscribed with the address (Figure 2). Before the eighteenth century, the exchange of handwritten letters had long been an essential practice among the powerful and socially elite who had political news to convey, alliances to negotiate, and far-flung family relations to maintain. Such exchanges, however, required not only relatively sophisticated skills in literacy and handwriting (and, often, the services of one or more secretaries) but also material tools – paper, quill pens, ink, sealing wax, blotting sand (“pounce”), and so on – and, above all, the means to procure or take advantage of state or private messenger services to convey written letters safely over long and sometimes perilous distances.Footnote 11 With the development of a London-centered postal service available to the public in the later seventeenth century, the founding of the Penny Post efficiently crisscrossing the city, and significant improvements to the national network of postal routes in the first half of the eighteenth century, the “familiar letter” genre became a widely cultivated form adapted to the everyday business, social, and personal needs of a very broad spectrum of the population, making this the golden age of letter writing. A solid grounding in the conventions of what Susan E. Whyman has called “epistolary literacy” offered the means to professional and social advancement and enabled an increasingly mobile population to maintain familial and business ties over great distances, including those between Britain and its colonies.Footnote 12

Figure 2 The address-bearing page of a letter from the Duchess of Portland to Elizabeth Montagu, 24 August 1747, mo227, p. 4, Montagu Collection, The Huntington Library.

As James Daybell has noted, “the material rhetorics of the manuscript page were central to the ways in which letters communicated”; this included such physical characteristics as size and quality of paper, formatting and wording of the sign-off, amount of blank space, and type and color of the seal. Yet, in what is often called the “Republic of Letters” – that is, the sphere of wide-ranging intellectual inquiry in which the most literate individuals of European states and their colonies participated – correspondence could become more: it allowed for in-depth and extended exchanges, often spanning decades and adapting to frequent relocations, on subjects of shared literary, historical, moral, and philosophical interest. Members of sociable literary networks circulated manuscript poetry or other short texts through enclosures in letters; letters also conveyed in return the constructive criticism that their authors sought.Footnote 13 More generally, a well-written familiar letter was in itself a literary creation, offering verbal wit, clever allusions, sententious wisdom, and moral commentary for the entertainment and improvement of its readers. While the letters of celebrated print-based authors “were increasingly used to construct authorial identity,”Footnote 14 both in their lifetimes and posthumously, epistolary talent in itself could form the basis of a literary reputation, and the letters of Elizabeth Montagu, as discussed in Section 3, were copied and circulated among her correspondents from the time she was in her twenties.

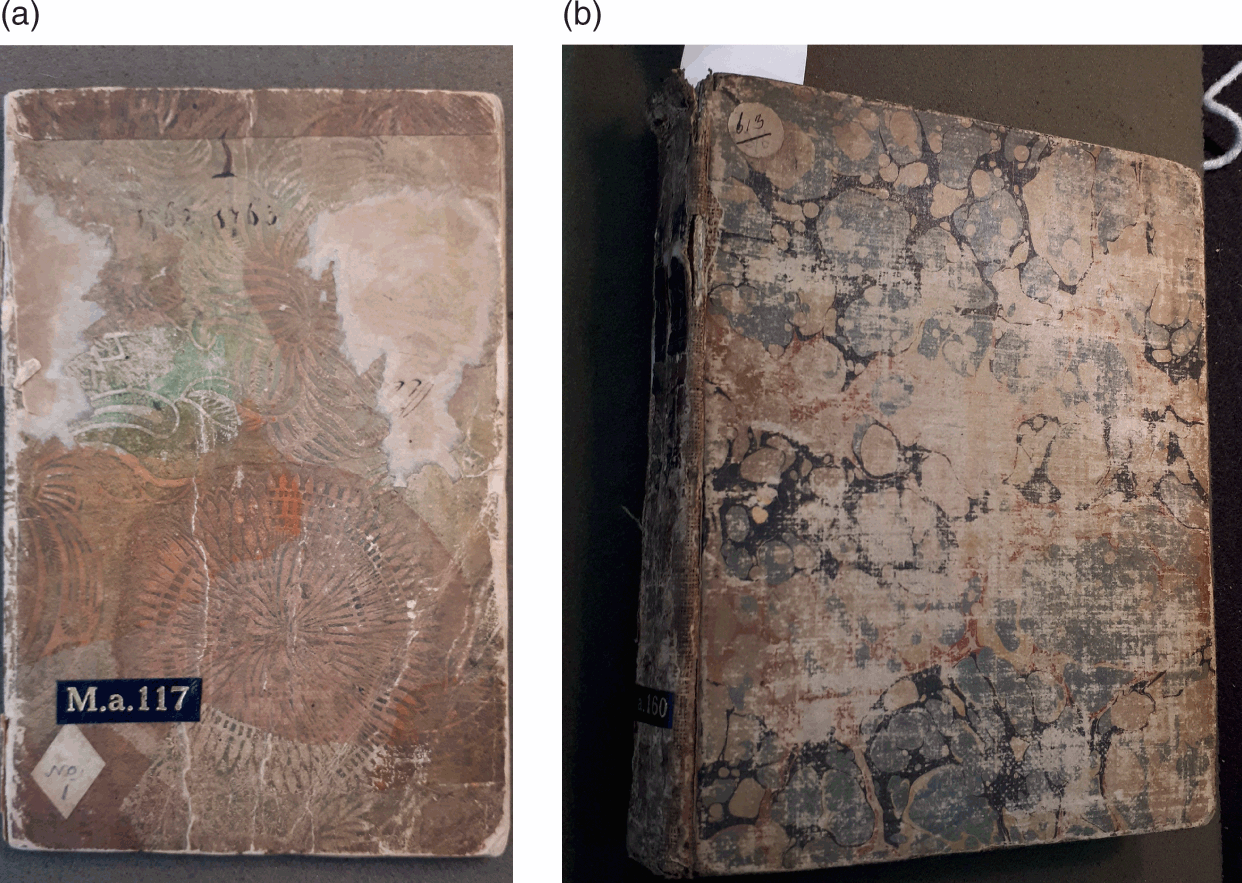

Loose sheets were also used in a variety of other ways: to compose an occasional poem (verses written to mark a particular occasion, such as a friend’s birthday or the death of an infant) for enclosure in a letter, for example; to record a sermon; or to record a poem that had been read in a book borrowed from an acquaintance or from a subscription or circulating library. Collections of these manuscript separates could be hand-sewn, pasted, or professionally bound into books, enhancing their chances of survival. More simply, multiple loose sheets could also be folded and placed into quires (sheets of paper folded once with folds placed together to create a booklet). Increasingly in the eighteenth century what we call notebooks – prebound blank paper-books – were purchased from stationers, as in the case of Sarah Wilmot’s and Dorothy Wordsworth’s books, discussed in Sections 2 and 4, respectively. Such prebound books might be of various sizes and qualities, sometimes with ruled margins and even ruled lines, with the smaller, simpler ones often covered only with a sheet of marbled paper and the quartos with stiffened cardboard covers (Figure 3). Among the most common manuscript genres for which stationers’ paper-books were used were commonplace books – organized collections of memorable or edifying quotations; miscellanies – collections, usually of poems, often sourced from print; scrapbooks – compilations of printed and manuscript materials as well as, often, watercolor sketches, fabric, pressed flowers, and so on; and albums – collections of solicited poems or other handmade items. As access to print increased and literary fashions changed through the long eighteenth century, these forms succeeded one another in general popularity, with scrapbooks and albums coming to the fore in the 1820s. However, many notebooks defy any single categorization, as they were often what Margaret J. M. Ezell has described as “messy,” “combin[ing] accounts of rents collected with copies of verses, alphabet exercises with prayers and diary entries.”Footnote 15

Figure 3 Notebooks covered with marbled paper and in the second case also with stiffened boards (Folger MS M.a.117 and M.a. 160).

For literary authors, as already noted, loose sheets were often used for enclosure of a work in a letter. The poet William Shenstone on several occasions writes to friends in an attempt to retrieve draft poems written on loose sheets that he has circulated for comment and then lost track of. In the case of a body of work or a longer work, handmade or purchased notebooks were useful for drafting, copying, and revising before the work’s wider circulation among manuscript readers or its submission to a bookseller for printing. Thus Elizabeth Montagu’s correspondence in the Huntington Library includes a folded booklet, held together by two small pins, of Hester Chapone’s poems, seemingly used to interest Bluestocking friends and influencers like George Lyttelton in Chapone’s work before she ventured into print. Some poets, such as Anne Finch, created volumes of their poetry in manuscript as an alternative to print; in Finch’s case, many of her currently most well-known poems remained unprinted until the twentieth century. Whether destined for confidential manuscript circulation or for setting into type for printing, such “fair copies,” unlike Shenstone’s working drafts of poems sent to friends for feedback, were carefully produced by the author or an amanuensis to maximize correctness and legibility.

1.2 Intermediality

If texts could take on multiple manuscript forms in the long eighteenth century, it is not surprising that they also moved back and forth between media. Poetry, in particular, inhabited a media ecosystem wherein script and print were closely intertwined. Poetry is the literary genre that appears to have circulated most widely in manuscript form in this period, alongside other popular forms such as epitaphs and riddles, both of which were often rhymed verses. The poems most likely to circulate in this way were short and could easily be copied and exchanged. Many were the kinds of occasional verse already described: highly social in nature; addressed to members of one’s social network as a means of sustaining personal relationships; and potentially copied, shared, or collected by others in the network or beyond who had gained access to the manuscripts. Other popular subgenres were topical satires, devotional lyrics, and courtship poems, all of which were of wide relevance or easily transferable to new contexts. When such a poem was submitted to a magazine or printed by a bookseller, it might achieve further circulation to a new audience. Since copying from print was also widespread, print publication of a poem did not prevent but rather stimulated more handwritten copying. Many poems were published in cheap miscellanies, short-lived periodicals, and regional newspapers; making a copy by hand could in these cases assist in the poem’s preservation and transmission. Poetry of course was also published in more substantial book forms, but such books were costly, leading to even more copying by those who could not afford the purchase.

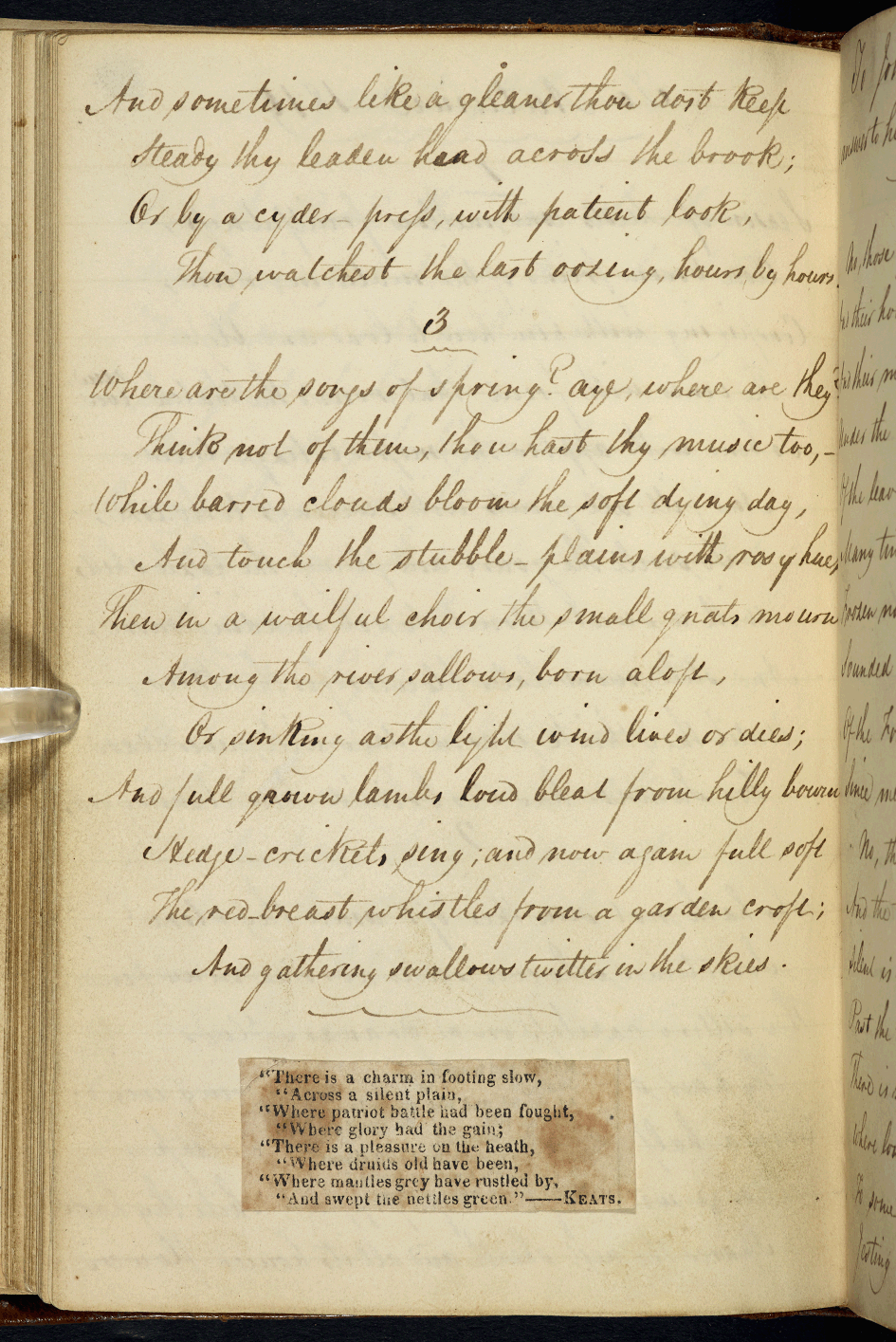

This extensive hand copying from print demonstrates that even after a poem had been published, manuscript circulation continued. Access and cost aside, copying could fill different needs than did possessing a printed version of a poem. The act of copying could involve copyists in creative activity, in the form of textual amendment (for example, readdressing a poem to a friend), arrangement in the company of other poems, and extra illustration (embellishment of a text through the addition of drawings, engravings, or other contextualizing materials). In the case of a very popular poem like Thomas Gray’s Elegy, discussed in Section 4, copying the poem by hand into a verse miscellany absorbed the poem into a personally curated collection; arranging, revising, illustrating, and/or reciting the poem made it one’s own.Footnote 16 And for a stylistically distinctive poem like the Elegy, making the poem one’s own often included copying or creating a parody of it as well.

Such forms of manuscript circulation occurred as a result of a text’s becoming public and therefore the object of widespread access. The latter half of the eighteenth century also saw printed pages become a kind of precursor to manuscript writing during the processes of literary production. Whereas in the early decades of the century, a press’s compositors generally had free rein over accidentals such as punctuation, by mid-century printers and booksellers increasingly involved authors in correcting the proofs of their works before they were published. In the case of Laurence Sterne’s 1765 novel A Sentimental Journey, we will see in Section 4 evidence of this developing tendency, though by no means a universal one. Given the limits of type and other equipment, a compositor would set a few sheets at a time, have these printed as proof sheets for correction, then solicit the author (or her agent) to make changes for the press workers to print, before proceeding to set the next section of the manuscript. The result was a print-manuscript hybrid that represented a collaboration between the compositor who had remediated the author’s manuscript into printed proofs and the author/agent who in turn remediated that proof into a marked-up manuscript for reprinting. In such cases, we can use an author’s manuscripts not necessarily to establish an authoritative text for a work but to learn more about the intermedial process of its composition.

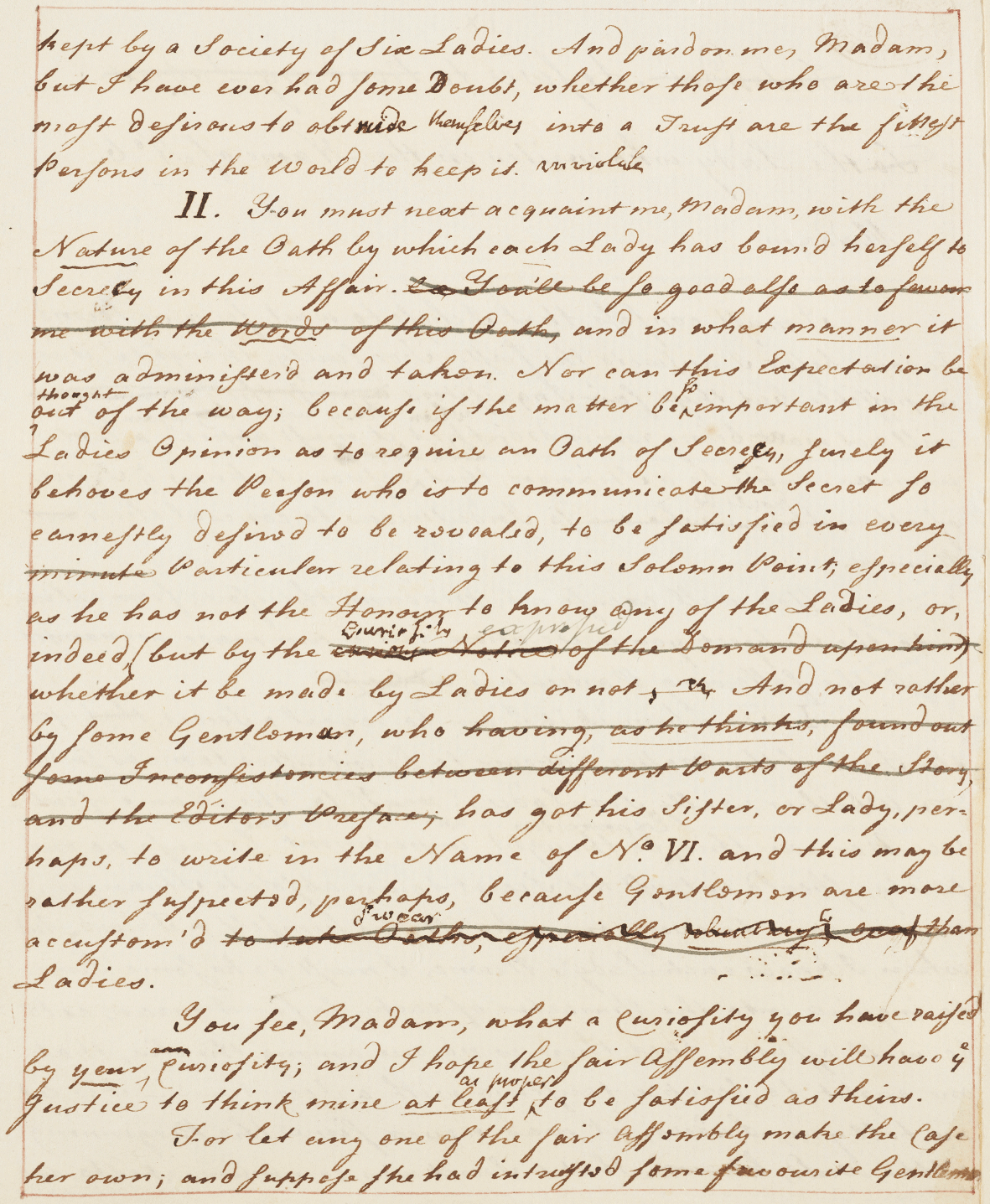

Markings on manuscripts can also reveal a less congenial movement through the publication process. In the case of Anna Letitia Barbauld’s 1804 edition of novelist Samuel Richardson’s correspondence, for example, William McCarthy has painstakingly analyzed the evidence of Richardson’s surviving manuscript letters in comparison with those in the printed edition to test the frequent accusation that Barbauld flagrantly altered, abridged, and spliced together her subject’s original manuscripts. This analysis has enabled McCarthy not only to determine which markings on the manuscripts are Barbauld’s, as opposed to those of Richardson, various family editors, and even printshop workers, but also to carry out a statistical analysis of Barbauld’s editorial actions and even to deduce the adversarial relations between Barbauld as painstaking editor and Richard Phillips as publisher insisting on speed above all. The result of McCarthy’s comparative study is a radical rehabilitation of his subject as editor and a valuable insight into the methods of a turn-of-the-century publisher.Footnote 17 McCarthy’s study of Barbauld’s editing of Richardson’s letters unexpectedly reveals as well the degree to which Richardson himself was the first mediator of his own manuscripts, altering and recopying them with imagined future print audiences in mind. Thus the example of the Barbauld edition highlights the changes to which even letter manuscripts, as textual objects existing in an intermedial ecosystem, are continually subject, whether they are reproduced in facsimile, print, or digital form. Richardson’s letters, and the additional handwriting and other marks that appear on them, demonstrate that manuscripts often reflect interventions made at various times, by various people, and that with meticulous study (and the aid of contextualizing evidence), it can be possible to decipher the different hands, the stages of revision, and the purpose behind these marks (Figure 4). These manuscripts also reveal that the concepts of “draft” and “fair copy,” terms that attempt to distinguish between incomplete and complete manuscript works, in fact exist on a continuum, as fair copies are transformed back into drafts through the processes of revision and correction.Footnote 18

Figure 4 The second page of a retained letter, in a copyist’s hand, from Samuel Richardson to “Six Reading Ladies,” c. March 1742, Forster Collection XVI, 1, f.20, showing subsequent changes in Richardson’s own shaky, elderly hand of the late 1750s and in Barbauld’s paler ink.

A manuscript page could be amended in many ways, and only some of these practices are recoverable. In one instance, a strike-through might allow us to read what was written beneath; in another, the original words might not be legible. A page could be removed entirely from a notebook, leaving no trace except possibly a stub of paper; another piece of paper could be sewn, pasted, or otherwise attached to conceal, sometimes permanently, what was originally beneath. From ink or handwriting we can sometimes discern the order in which changes were made, but we often cannot make these determinations. In these ways, manuscripts are incomplete witnesses to their history. At the other extreme, fair copy manuscripts with few markings, though they hide the writing process, can tell us a great deal about how literary texts circulated; the existence of variant fair copies of a single literary work, for example, can delineate a social circle and also point to ways literature was contextualized and personalized for different audiences over time. While the stories uncovered through manuscript study vary widely, the cases examined in this Element yield knowledge of literary sociability and production in the eighteenth century that could not be gained by any other means. These rewards, and the challenges we face in pursuit of them, are reflected throughout our discussions in this Element.

2 Manuscript Verse Miscellanies

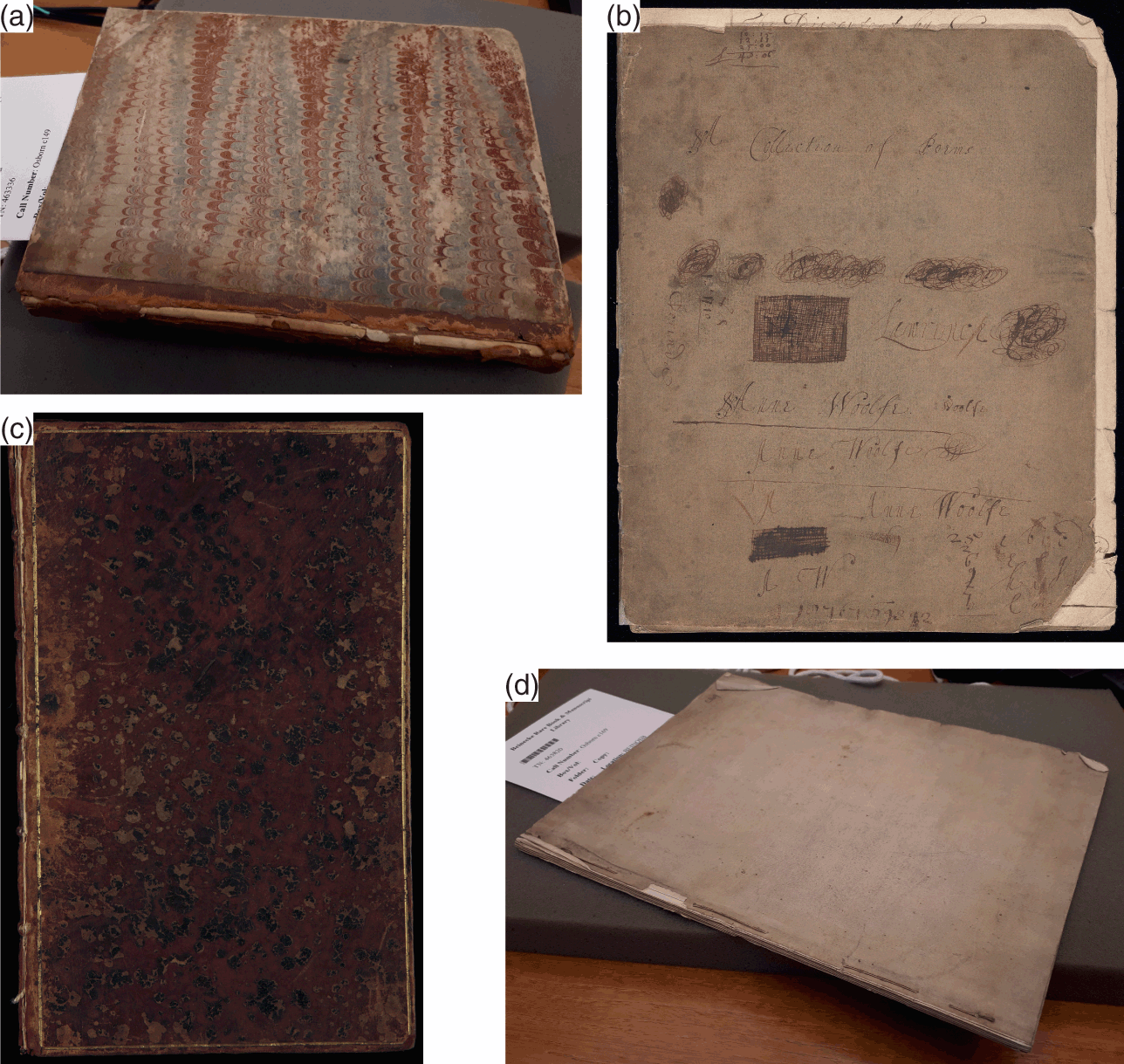

During the eighteenth century, young women, old men, and anyone in between who could read and write and had access to texts, paper, and writing implements might at some point create a manuscript verse miscellany of their own. Extant in libraries, archives, and private collections today are hundreds, likely thousands, of such volumes, each to some degree a coherent aestheticized object (Figure 5).

Figure 5 A sampling of manuscript verse miscellany covers (Beinecke Osborn c.149; c.258; c.154; c.169) from the James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Typical verse miscellanies offer a collection of predominantly contemporary, generally short poetry copied in a single hand, very often including local or “original” verse from within the compiler’s own circle alongside materials taken from print sources such as magazines. In most cases, they begin as a bound book of blank paper; the poetry is copied in a careful, fair hand, often with uniform, decorative flourishes between items, sometimes with the addition of title pages, signatures, tables of contents, and even illustrations. These shared features suggest that their compilers were working with a sense of certain common practices for creating something new from available poetic materials. However, as Oliver Pickering has written of the manuscript miscellanies in the Brotherton Collection at the University of Leeds, each book represents “a unique act of compilation arising out of a particular set of circumstances” that makes it “more than the sum of its parts.”Footnote 19 Why was this act of curation undertaken? Who was its creator, and who did they imagine as the audience for this book? What tastes or conventions guided the choice and arrangements of contents? Finally, what do these patterns make legible about poetic culture in the eighteenth century? Exploring such questions can reveal something about how individuals who were not cultural elites or metropolitan literary professionals encountered, engaged with, and created poetry.

In particular, such books reveal the inherent sociability of poetic culture, whereby the production, circulation, and reception of verse were woven into educated individuals’ social networks. Manuscript poetry books attest to their function as objects of entertainment, education, and commemoration, in the form of occasional verse addressed to immediate family members and close friends; lines discussing local events; adaptations or imitations of popular poems to make them personal; and performative works of wit and formal complexity that are clearly intended to enhance a literary reputation. When their compilers and geographical origins can be determined, manuscript verse compilations provide valuable documentation of little-known literary networks of the time, whether school- and university-based coteries, interconnected Bluestocking circles, fashionable English and Irish coteries that overlapped at the cottage of the “Ladies of Llangollen,”Footnote 20 or the far-flung Quaker movement that created an identity for itself through poetry and letters. Together, manuscript verse miscellanies demonstrate the role of verse in everyday life, providing a context for the more well-documented sociable authorship of writers such as Jonathan Swift and Jane Austen. This section will discuss a compilation found by Betty Schellenberg, one of this Element’s authors, in the Chawton House Library in Hampshire, England, illustrating how she pieced together at least some of the story of the book and the literary sociability embedded in its pages.Footnote 21 One theme of this compilation is the celebration of leading women, suggesting that scribal authorship might have sustained poetic traditions that did not welcome the more public glare of print. At another level, the miscellany reflects the affective, educational, and memorial functions of collecting poetry within the gentry and middle classes, and by extension, in the lives of individuals on the margins of public literary culture.

2.1 Engaging a Manuscript Poetry Miscellany

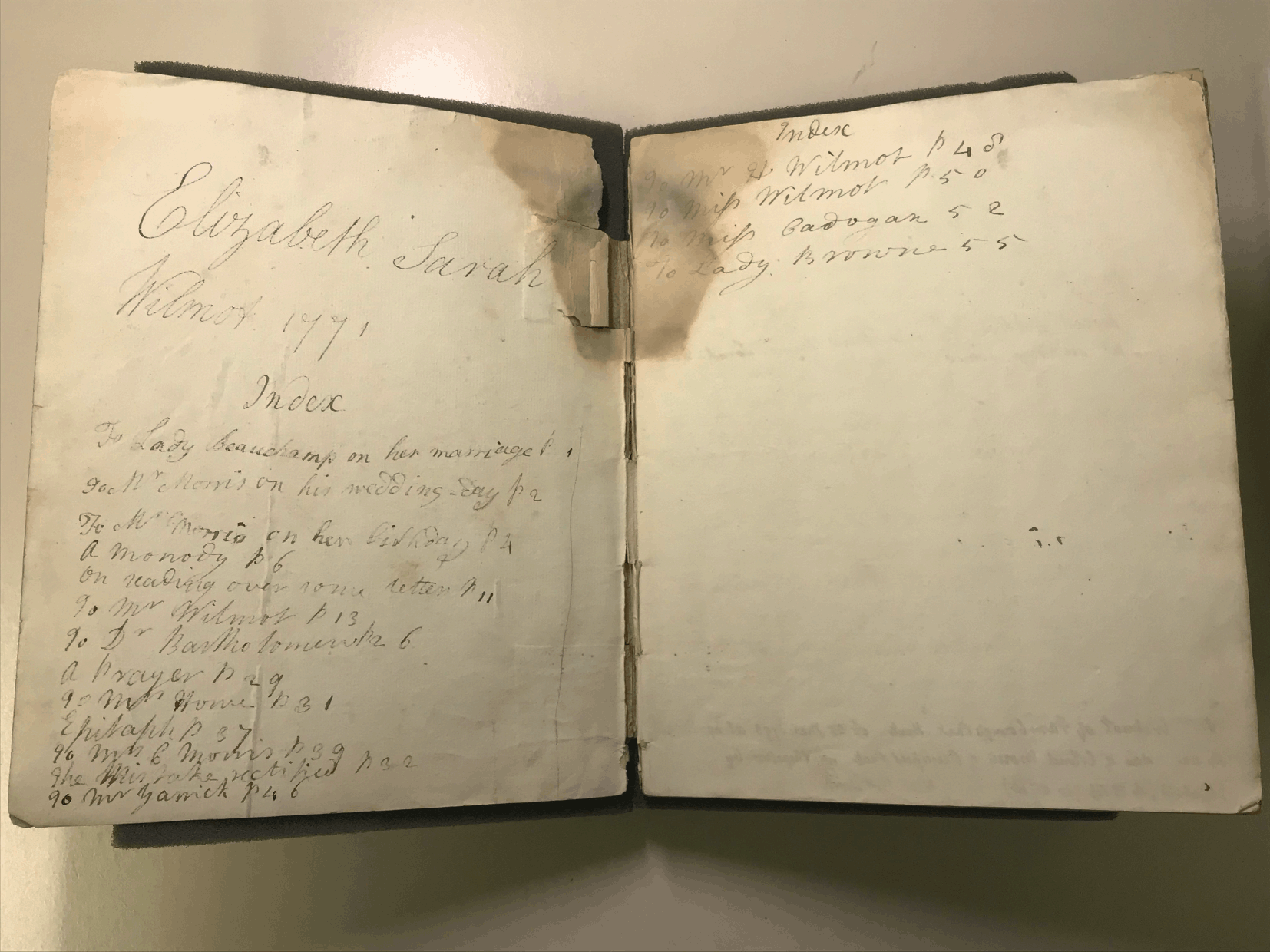

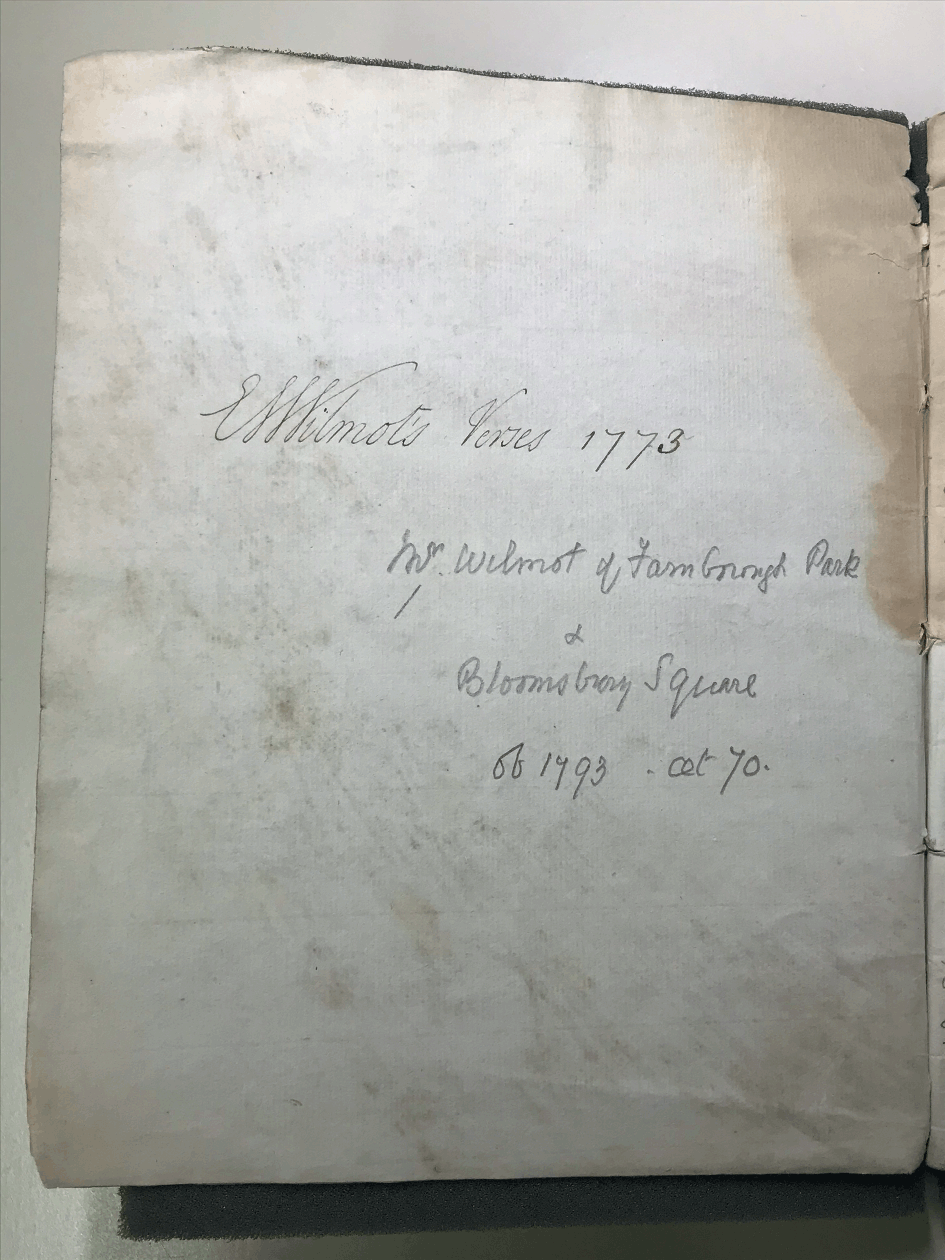

In the spring of 2017, when I was privileged to hold a fellowship at Chawton House, I was handed a package of manuscripts cataloged simply as “Wilmot, Elizabeth Sarah, Three manuscript notebooks of verse, 4946 WIL.” Opening the first notebook, a small quarto covered with marbled paper (Figure 6), I found on the inside cover the signature “Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot 1771,” followed by a list of contents in a more informal hand (Figure 7). This signature matched the hand and title of the remaining two notebooks, labeled “ES Wilmot’s Verses 1773” and “ES Wilmot 1776” (later altered to “ES Wilmot’s Verses”), respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 6 The cover of Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot’s first notebook, 4946 WIL, Chawton House Library.

Figure 7 The inside front cover of Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot’s first notebook, 4946 WIL, Chawton House Library.

Figure 8 Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot’s signature inside the front cover of the second notebook, 4946 WIL, Chawton House Library. The form of the “ESW” letters closely matches the “SW” signature at the bottom of two of the notebook 1 poems (Figure 10). The later annotation erroneously identifies “ESWilmot” as Mrs. Wilmot who died in 1793.

What ensued was a process typical of manuscript research when one encounters materials created by writers unknown to literary history. Often kept for a century or two by their creator’s family or friends, such manuscripts may come to an archive along with family papers or some other contextualizing collection, but since they were initially created for audiences who knew what they were seeing, they often do not present themselves in ways that are readily intelligible. In this case, even the context was nonexistent: Chawton House has no record of the provenance of the notebooks, which the catalog describes briefly as “verse on family matters written between 1744 and 1785 by Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot, of Farnborough Park, Hampshire.” On the verso of the second leaf of the first notebook, I read, again in the more informal hand: “Verses written by my Dear Mama Sarah Wilmot at sundry times.” A later annotation of this label told me that Mrs. Wilmot of Farnborough Park had died in 1793 at the age of sixty-nine; a similar annotation of “ES Wilmot” in the second notebook again identified the same Mrs. Wilmot. Based on the catalog entry and these signatures and annotations, I began with the assumption that the poet and compiler of the three books was a Mrs. Elizabeth Sarah Wilmot who had been known as Sarah, and whose first book had later been annotated by a daughter or son. In fact, almost every poem in the book was signed by a distinctive scrawl-like device that can be read as an “S” or “Se,” supporting the theory that Elizabeth Sarah had gone by the name Sarah or even used an inverted version of her two given names (Figure 9).

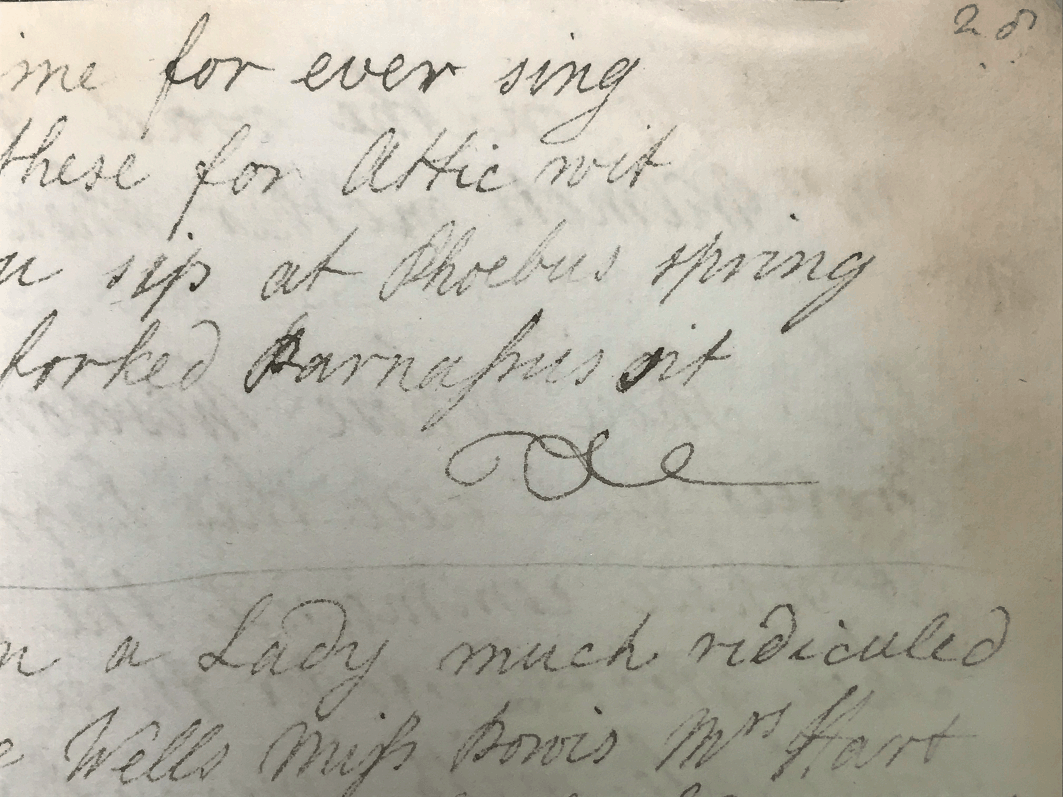

Figure 9 Sarah Wilmot’s “S” or “Se” signature, 4946 WIL, notebook 1, p. 28 detail, Chawton House Library; this mark is found at the end of most of the poems in the first notebook.

Online searches yielded transcriptions of memorials in St. Peter’s Church of Farnborough, Hampshire, including Henry Wilmot, d. 1794, aged eighty-four, and his wife Sarah Wilmot, d. 1793 at the age of sixty-nine. The dates were right, but nowhere was this Sarah Wilmot referred to as Elizabeth Sarah or Sarah Elizabeth. When the monuments at St. Peter’s yielded a further memorial for “Elizabeth Sarah Wife of James Seton of London and Daughter of Henry and Sarah Wilmot,” who died on February 5, 1803, aged forty-three, the clues realigned themselves: Elizabeth Sarah was Sarah Wilmot’s daughter, born between February 1759 and January 1760, who would have been just eleven or twelve years old in 1771 when she signed and dated the first notebook – too young to be composing such poetry, but old enough to begin to copy out her mother’s poems. This hypothesis was supported by the headers of the poems, which indicate a third-person perspective and a need to spell out the occasion of writing for the notebook’s potential readers – for example, “Epitaph / On Mrs Mary Lamb Novr: 1767 who had lived twelve years with Mrs Wilmot first as her own maid & afterward as housekeeper & married in her service.”

Returning to the puzzle of the signature, I observed that in addition to the “S” or “Se” mark, a more calligraphic device is found in notebook one. This more elaborate form appears to be an “SW,” clearly produced by the same hand as that of the “ESWilmot’s Verses 1773” of the second notebook, shown in Figure 8. The elaborate “SW” occurs twice, once alone and once, after the penultimate poem, above the simpler “S” (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Elizabeth Sarah’s notation “SW” at the bottom of her mother’s poem to her son Valentine Henry, followed by Sarah’s endorsement. Notebook 1, p. 49 detail, 4946 WIL, Chawton House Library.

I now believe that Sarah checked and endorsed with her scrawl device the copies made by Elizabeth Sarah, who in two cases marked her completed copy with her mother’s initials. It appears, then, that notebook one is in the hand of Sarah Wilmot’s daughter, Elizabeth Sarah. The booklet may well be the product of a pedagogical exercise when eleven-year-old Elizabeth Sarah was being educated at home in handwriting, poetry, and taste but had not yet begun to write poetry of her own. As Kathleen Keown has argued, the production of occasional poetry was often among the polite accomplishments considered important for genteel young women of the period; it would not be surprising that her mother, herself a practiced poet, took care to instruct her daughter in the art.Footnote 22 This interpretation is reinforced by the fact that the important final position in the notebook is given to a poem praising Elizabeth Sarah’s budding efforts to pursue the Muses. It begins: “My Dearest Child my much loved Treasure/ Your lines I read with rap’trous pleasure/ To see the sacred Sisters thus inspire/ Your early Mind with their poetic fire.” As one of my students wrote of it, “the lavish praise Wilmot gives her daughter serves as encouragement to join” the “tradition of sharing and supporting writing” that was a feature of the Bluestocking networks.Footnote 23

I have outlined the extended process of piecing together this book’s story to illustrate the false starts and imaginative engagements involved in such work. The motivation to pursue the chase, however, was what I found as I immersed myself in the contents of this first notebook. From previous work with manuscript verse miscellanies, I assumed I would be reading a sprinkling of occasional poems by an obscure provincial lady, interspersed among verse copied from contemporary print sources or contributed by members of her circle. Indeed, in this first notebook there were the verses marking family events: “To Mr Morris on his wedding-day,” “To Mrs Morris on her birth-day by her Daughter Mrs Wilmot January 7th 1746/7,” “From Mrs Wilmot in the Country to Mr Wilmot in Town Decr: 11th 1754,” and so on. While there did not seem to be any poems copied from print, there was a short, witty piece by the retired celebrity actor and theater manager David Garrick urging his physician friend William Cadogan to stop displaying his lack of taste by criticizing Shakespeare. From the start, however, I was struck by how unusually accomplished Mrs. Wilmot’s poetry was. The fourth poem, for example, “A Monody to the Memory of Mrs. Cadogan upon reading Milton’s Lycidas by her particular friend Mrs Wilmot” – opens with a strikingly rhythmic and polished invocation of the muse:

It made sense that the notebook would be almost entirely devoted to her work, unlike many others where original poetry is minimal or nonexistent; Mrs. Wilmot must have had somewhat of a reputation as a social author.

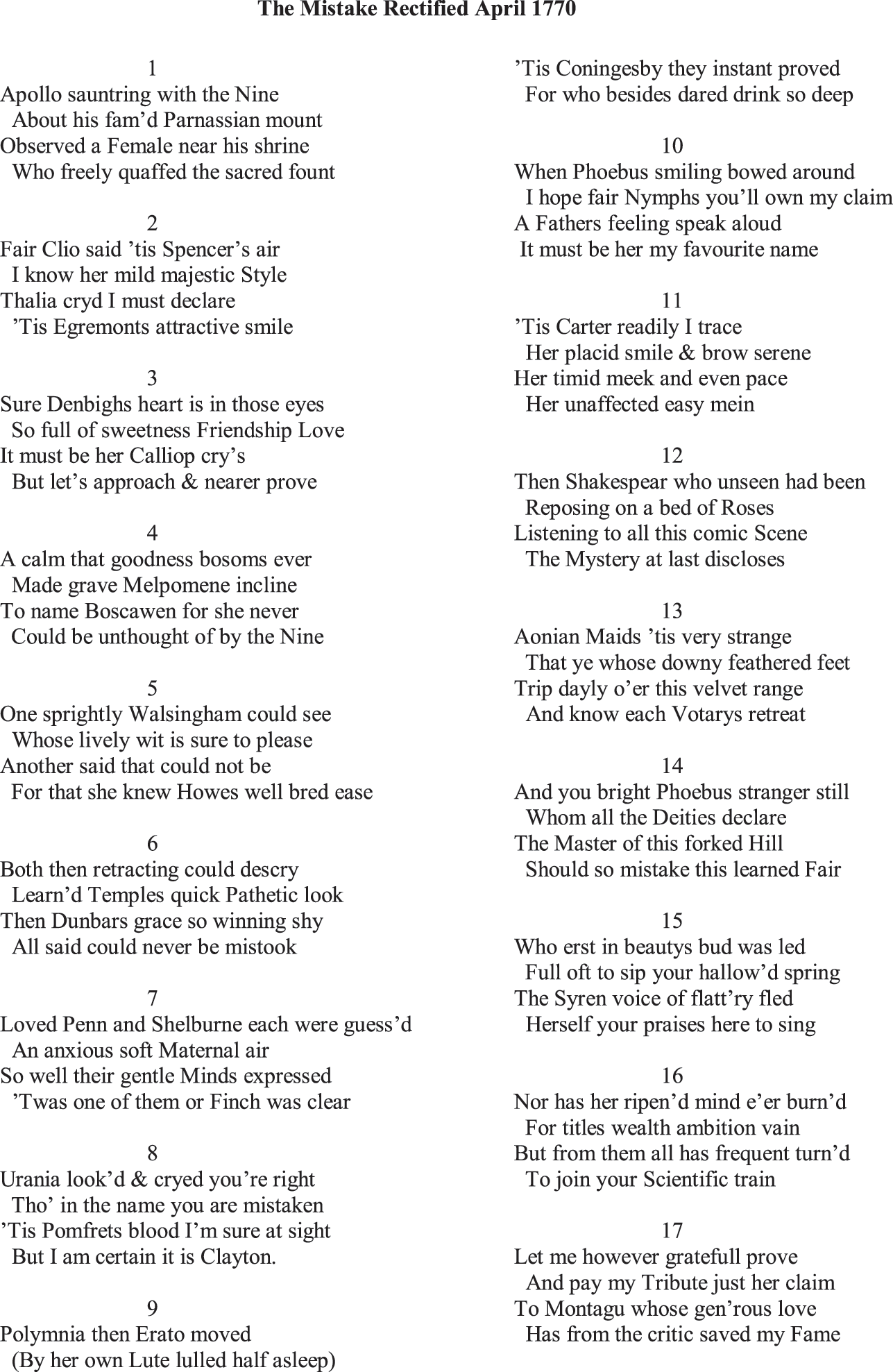

The first real shock of recognition, however, occurred in the ninth poem, a mock-epic account of a chess match addressed “To Mrs Howe” and, on the basis of internal evidence, composed in about 1760. When this poem posed a rhetorical question:

I could not miss the reference to a short-lived configuration of leading Bluestocking women – Elizabeth Carter, Elizabeth Montagu, and Anne Pitt. This inherently unstable grouping, as Deborah Heller has anatomized it, existed only between 1759 and 1761, after which Montagu turned definitively from Pitt’s brilliantly unstable wit toward the more intellectually and morally serious Carter. Wilmot is thus recording her proximity to the Bluestocking phenomenon right at the point of its emergence.Footnote 24 Poem twelve in the collection, titled “The Mistake Rectified April 1770” (Figure 11), underscored the significance of Carter and Montagu for Wilmot. In a series of seventeen carefully numbered stanzas, Apollo and the Muses, “sauntring” about on Mount Parnassus, try to identify a mysterious woman drinking from the Castalian spring. Fourteen leading contemporary women are proposed as candidates and praised in turn, before the poem deduces, with the help of Shakespeare, that the “learned fair” is “Montagu,” to whom Shakespeare is grateful for the “gen’rous love/ [That] Has from the critic saved my Fame.” The very specific dating of this poem – April 1770 – now came into focus for me: Elizabeth Montagu had published her famous Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear … with Some Remarks upon the Misrepresentations of Mons. de Voltaire in May 1769, and the work’s authorship had gradually become known through the final months of the same year; its second edition appeared in 1770. I was reading what is known as a “Sessions of the Poets” poem, a witty subgenre in which Apollo is called upon to adjudicate the claims of a competing group of contemporary writers. As this section will go on to explain, the tradition tended to be masculine and misogynistic; its use for a poem honoring Montagu and also, it seemed, a whole collection of admirable women, hinted at a possible manuscript-based resistance to this tradition. To borrow Pickering’s phrasing, the “particular set of circumstances” out of which Mrs. Wilmot’s poetry arose, what made this notebook “more than the sum of its parts,” was its apparent insider perspective on an important eighteenth-century cultural phenomenon, its hints of a hitherto-hidden network of literary exchange between country gentlewomen, and its demonstration of how a daughter might be educated in the mid-eighteenth century.

Figure 11 Transcription of “The Mistake Rectified” by Sarah Wilmot, notebook 1, pp. 42–46, 4946 WIL, Chawton House Library.

I was now keen to find out more about the talented but unknown Mrs. Wilmot, and especially about her social and literary connections. Various genealogical sources, Wikipedia, eighteenth-century travel accounts, and the Orlando textbase entries for Wilmot’s daughter-in-law all contributed insights. Sarah Morris Wilmot, born in 1723, was a close contemporary of the “Queen of the Blues” Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, born in 1718, and her younger sister Sarah Robinson Scott, born in 1720. The daughter of Colonel Valentine Morris and Elizabeth Wilmot Morris, she married her father’s cousin Henry Wilmot, a barrister and from 1768 lord of the manor of Farnborough Park, Hampshire. Sarah’s father was a West Indian planter and Sarah may have spent the early years of her life on a sugar plantation, but this origin is not mentioned in her verse. With his acquired wealth, Colonel Morris purchased the estate Piercefield in Wales, near Chepstow, and it is of Piercefield that she writes nostalgically in her extant poetry.Footnote 25 As for Elizabeth Sarah, she became a recognized pastel artist and the mother of a judge of the supreme court of Calcutta.

It is more difficult to tease out the formation of a manuscript poet’s literary networks and her standing within them, even with the help of poems referencing her connections to well-known figures such as Montagu and Garrick. The Wilmots do feature in editions of Garrick’s correspondence, although without any annotation of who they were. This friendship may have arisen with a connection between Henry Wilmot and Garrick. A collection of miscellaneous Garrick-related notes and poems at the Folger Shakespeare Library includes a short occasional poem on the 1766 appointment of Charles Pratt, Lord Camden, as lord chancellor; in these verses, Henry Wilmot serves as interlocutor and addressee of Garrick. A facetious 1771 note from Wilmot to Garrick claims that a Mr. Phillips is dunning him for a literal or metaphorical debt incurred by Garrick.Footnote 26 Subsequent correspondence makes it clear that Mrs. Wilmot herself was a conduit of news between the Garricks and their friends, as well as an influence broker, bringing authors to Garrick’s attention and working with him to assist others through her connections with aristocrats. The playwright Elizabeth Griffith, for example, writes to Garrick in 1770 that “Our good and amiable Mrs. Wilmot told me that you were involved in so many engagements to authors, that you regretted it was not in your power to receive any piece from me.” On another occasion, Garrick tells Sarah, “Your friendship and affection is all turnpike [i.e., a smooth, modern roadway], and there is not a single jog upon the whole road.”Footnote 27 The embeddedness of Garrick’s above-mentioned playful attack on Dr. Cadogan in a network of literary sociability that included Garrick, the Wilmots, and the Cadogan family is evidenced by the conclusion of a 1773 letter to Garrick from Dr. John Hoadly: “In return for this [some enclosed lines of verse], I expect you to send me the wit between Dr. Cadogan and you, which made his daughter cry at Mr. Wilmot’s.”Footnote 28 In this world, literary production is an everyday sociable pleasure, and wit and influence are wielded in tandem, leaving their traces in the manuscript forms of correspondence and the poetry miscellany.

2.2 “The Mistake Rectified”

Sarah Wilmot’s place in Elizabeth Montagu’s Bluestocking network is more difficult to trace, in part because the vast Montagu correspondence has never been published in its entirety. Montagu and her sister Sarah Scott do casually mention the exchange of books and letters to and from Mrs. Wilmot in their letters to each other, and in 1769, the Wilmots dined at least once with Montagu while accompanying their son back to Eton.Footnote 29 An anonymous manuscript poem in the Montagu Collection whose author had not previously been identified, the monody on the death of Frances Cadogan quoted earlier, can now be attributed to Wilmot on the evidence of the Chawton House notebooks. Although there was significant overlap between the Bluestocking and Garrick social circles,Footnote 30 there may have been an older, familial connection between Montagu and Wilmot. “Morris,” Wilmot’s maiden name, was also the maiden name of Montagu’s maternal grandmother; the family home of “Mount Morris” in Kent was Elizabeth’s mother’s inheritance; the name was not only adopted by the eldest Robinson brother upon his inheritance of Mount Morris but was also the given name of another of Elizabeth’s brothers. Thus “The Mistake Rectified” was surely composed to be shared with Montagu and likely Carter and other women it describes, just as an earlier manuscript poem “The Circuit of Appollo [sic],” written at the turn of the century by the celebrated poet Anne Finch, Lady Winchilsea (1661–1720), was composed to be circulated among a group of Kentish women poets Finch wanted to celebrate.

The lineage of the “Sessions of the Poets” subgenre has been traced through the seventeenth century by Claudia Thomas Kairoff.Footnote 31 Kairoff argues that Finch’s “Circuit of Appollo” breaks with the casual misogyny of this tradition to praise a circle of local female poets in an equally witty but more mutually affirmative manner. The mise-en-scêne of Finch’s poem ends with Apollo declining to award the laurel wreath to any one poet, deciding at the last moment that it is not advisable to arouse female jealousy by selecting one woman over the others. On the way, however, Finch has referenced six female poets, mentioning Katherine Phillips and assessing Aphra Behn, before praising the achievements of four contemporaries.Footnote 32 Wilmot’s poem shares with Finch’s not only a focus on an interconnected network of accomplished women but also an affirmative spirit: she finds something to praise in each of a succession of women before awarding the ultimate prize to Montagu. Although the form and meter of the two poems differ, Wilmot echoes Finch in the conversational humor of the scene, and in the prominent role assigned to the Muses. In Finch’s poem, the Nine are left to decide the question when Apollo absconds; in Wilmot’s, they conduct the initial review of women until Apollo and Shakespeare step forward to determine the identity of the mysterious female who is “freely quaff[ing]” Apollo’s “sacred fount.”

At the same time, there are significant differences between the two poems. These differences can be seen as reflective of a more public cultural role for the women named by Wilmot, one mediated through print-based celebrity. Even though, like Finch, she is apparently writing a poem for coterie circulation, Wilmot names fifteen women in all, and she does so explicitly, rather than using the typical pastoral pseudonyms that create an effect of “intentional obscurity” in the earlier poem.Footnote 33 In fact, nine of Wilmot’s fifteen subjects are identified not by Christian name but by aristocratic title, signaling their status and position through marriage in a patrilineal social hierarchy. Lady Juliana Penn; her sister Charlotte Finch; and their niece Sophia Carteret, wife of the second Earl of Shelburne, are explicitly grouped together by “blood,” as the daughters and granddaughter, respectively, of the first Earl of Pomfret. Thus, the overall effect of naming in the first half of the poem is one of public, stylized display – a red-carpet parade, or perhaps a formal court presentation – rather than intimate mutual praise and encouragement. The poem reflects Clarissa Campbell Orr’s observation that in the first decades of King George III’s reign, court culture and Bluestocking culture were very much aligned, precisely through individuals such as Lady Charlotte Finch and Lord and Lady Shelburne, and around cultural projects such as the promotion of the arts and sciences and the moral education of the nation’s leaders.Footnote 34

Given the prominence of naming and pedigree in this poem, it is perhaps not surprising that “The Mistake Rectified” limits its praise of most of its subjects to a single attribute or two, and that those attributes tend not to literary production or even conversational skills but rather outwardly visible traits – a “mild majestic Style,” an “attractive smile,” “a calm that goodness bosoms ever,” or “an anxious soft Maternal air.” Even Elizabeth Carter, the penultimate female figure and “favourite” of Phoebus whom the reader would recognize as a poet and translator of the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus, is commended for “Her placid smile & brow serene/ Her timid meek and even pace/ Her unaffected easy mein [sic].” In short, one might on first reading conclude that admirable female publicity among the Bluestocking network, or at least in Mrs. Wilmot’s view, must adhere to traditional social hierarchies and to rigid expectations of modesty, grace, and maternal softness.

Like Finch’s “Circuit of Appollo,” the poem can nevertheless be appreciated as a celebration of female intellectual achievement, one that is of its particular time and context. First, the conceit of the poem rests on the implicit claim that these women need no introduction, that Apollo and the Muses should be able to recognize from a single external sign exactly who these women are and what they stand for. The approach is at once distant and familiar: since everyone knows what each of the women is famous for, it hardly needs to be said. In this respect, Wilmot’s poem becomes a kind of harbinger of the decade of the 1770s, when the iconography of female achievement became a frequent feature of patriotic public culture. Second, a number of the descriptions convey more than what first appears to the twenty-first-century reader. The ancestral gesture to Pomfret blood described earlier was likely heard by Wilmot’s first audience as matrilineal rather than patrilineal, a reference to the three women’s mother and grandmother Henrietta Fermor, Countess of Pomfret, known for her literary correspondences with an earlier generation of learned women. Those seemingly superficial and clichéd descriptions are in fact revealing. For example, the Muses’ debate about whether it is Penn, Shelburne, or Finch who displays “an anxious soft Maternal air” may be less about idealizing women’s natural maternal qualities than about a more specialized expertise: Lady Juliana Penn was very involved in the management of her husband’s three-quarter share of the Pennsylvania colony on behalf of her family; Lady Shelburne was known for the care that she and her husband, the second Earl, were devoting to the education of their sons; and Lady Charlotte Finch was governess to the royal children.Footnote 35 Even the description of Carter as above all “placid,” “serene,” and moving at an “easy” pace evokes the Stoic philosophy that she had helped popularize.

A final indication that this poem values female intellectual achievement is found in its overall trajectory toward the culminating description of Montagu. Arguably the poem moves in a deliberate progression through its list of aristocrats toward an increasing emphasis on education and learning. Montagu is specifically praised as a “learned Fair,” one who “fled” “flatt’ry” even in her time of youthful beauty to sing the praises of Apollo, one who possesses a “ripen’d mind,” and who turns away from “titles wealth ambition” to join the “Scientific train.” As the culminating character sketch of the poem and the description of the contest winner, Montagu’s portrait represents an ideal use of female wit. A non-aristocrat, Montagu here is made notable not for her beauty, wealth, or social connections, all of which were indeed conspicuous, but rather for her learning and contribution to literary criticism. Her emergence as the contest winner can be read as underscoring the poem’s implied critique of another kind of conspicuous woman: overtly political aristocrats like the Duchesses of Bedford, Northumberland, or Devonshire who wielded formidable dynastic political power through elections and patronage.Footnote 36 Mrs. Wilmot, it seems, believed that women had a public cultural role to play, and she was prepared to name the women she admired for doing so.

2.3 A Female Literary Tradition in Manuscript?

Of the fifteen Sarah Wilmot poems preserved in the first notebook, five of them can be seen as explicitly celebrating or defending women’s talents and achievements. Besides two poems honoring Frances Cadogan, the account of an epic chess match between two women, and “The Mistake Rectified,” another notable poem in the book, “To Dr Bartholomew at Tunbridge Wells on his having wrote many Lampoons Satyrs &c,” admonishes the addressee in 1759 to turn away from satires of women in favor of an array of fourteen admirable women, from the Duchess of Richmond to Wilmot’s own sister Caroline Morris. Singing their praises, the speaker promises, would allow Bartholomew to exercise his “Attic wit” and “sip at Phebus’ spring/ And on the forked Parnassus sit.”Footnote 37 Given her commitment to acknowledging female worthies in her poetry, the question arises as to whether Wilmot might have known of the “Circuit of Appollo” poem composed by her Kentish predecessor. While we have so far no evidence for Finch’s “Sessions” verses having appeared anywhere in print between her death in 1720 and the 1759–70 dates of these poems, there are a number of linked networks through which limited manuscript circulation might have occurred. Although space constraints prohibit full elaboration here, one possible route is copies of Finch’s poems in the possession of Finch’s great-niece Frances Thynne Seymour, the Countess of Hertford (later Duchess of Somerset); we know that Hertford showed her collections of manuscripts to guests such as Catherine Talbot, friend of Carter and Montagu, and Thomas Birch, both featured in Section 3. An additional probability, suggested earlier, is that the living female poets described in Finch’s “Circuit of Appollo” would have received copies from her, which might have resulted in a fairly robust, if controlled, circulation of the verses. Such a poem might have been particularly valued within networks of country gentlewomen who would have enjoyed its sly celebration of the renown of provincial poets like themselves. All of this might have been true without the poem ever escaping the confines of a few select provincial networks.

Elizabeth Montagu’s publication of An Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear in 1769 might be seen as a point of arrival in the unofficial campaign of Bluestocking women to influence the social, moral, and cultural realms. Such influence operated not only through the conversational gatherings they hosted in their drawing rooms during the London season but also through their actions as overseers of families and estates from their residences in the country – spheres of action linked by correspondence networks whereby poems of commendation circulated as well. Within such channels of controlled circulation, influential poems may have generated other works without our being aware of the chain of transmission. If we cannot as yet trace the place of “The Mistake Rectified” in a manuscript literary tradition, an awareness of how the world of literary sociability functioned indicates that such a tradition may, indeed, stretch all the way back to Anne Finch’s “Circuit of Appollo.”Footnote 38

Paula Backscheider has pointed out that the sheer quantity of women’s poetry that has likely been lost makes it nearly impossible to determine whether the poetry we do have is part of a larger pattern or tradition. Discovering Sarah Wilmot’s previously unknown poems enables us to trace new lines of connection between literary women and men of the Bluestocking era. Beyond this level of historical evidence, what is the value of such findings for the researcher of eighteenth-century literary culture? First, the notebooks Elizabeth Sarah created as a girl illustrate the place of poetry in educational practice, particularly for women. Over the course of the three books, we see a young adolescent learning, by copying her mother’s most important poems, not only fluid handwriting but also elegant poetic expression and the social function of verse and wit in the maintenance of social ties. Second, Wilmot’s use of several of her major poems to celebrate female friendship, intelligence, and achievement in the arts and education can be seen as preserving a mid-century spirit of female solidarity and initiative, and as passing that legacy on to her daughter. Finally, the poems’ allusive and imitative character also hints at a counter-canon of writings that coterie authors might have appreciated and been influenced by, even as some of these works may now have been lost to our knowledge. Such canons may include, as in this case, feminocentric works such as Pope’s representation of Belinda’s mock-epic triumph at ombreFootnote 39 but also Finch’s “Circuit of Appollo.”

Manuscript records can help fill gaps that we did not even know existed. If they can bring to light the poems of a networker like Sarah Wilmot who for unknown reasons chose to remain “hidden” in coterie circles, they may also do so for lost works of writers like Phillis Wheatley, profoundly marginalized by intersecting conditions of status, religious affiliation, geographical location, and race. Often the record of those who are obscure or marginalized in their own times, through choice or obstruction, becomes fragmentary or even disappears from literary history. By contrast, our next section looks at how much carefully preserved collections of the correspondence of culturally prominent individuals can reveal about literary sociability in the eighteenth century.

3 Familiar Correspondences

This section will consider the familiar correspondence, both as a guide to how literary sociability functioned in the eighteenth century and as a creative artifact in its own right. As described in Section 1, the familiar letter is a handwritten text that at once documents and bears the physical traces of the labor of letter writing, as it was variously facilitated, structured, or impeded by geographical location, postal schedules, social networks, medical conditions, and even the seasons of the year. The familiar letter was also, in the eighteenth century, a valued literary form. Eighteenth-century writers and readers were attuned to epistolarity as a skill to be nurtured, wielded for strategic purposes, and appreciated for the instruction and entertainment it offered. For scholars today, extended familiar correspondences, in particular those that follow a social relationship and the dialogue it generates over a period of many years, offer us not simply a record of friendships, composition processes, or publishing transactions but also a picture of how sociable literary networks might be built over time, how tastes and critical principles might be developed through dialogue, and how letters were received and circulated as literary objects. In this section, three long-term correspondences (lasting between twenty-five and seventy years) will be used to illustrate each of these dimensions in turn. As an ensemble, the three demonstrate how a correspondence can be approached as a collaborative text that develops and documents its own unique terms and identities.

Our three examples are drawn from a 1741–65 series of weekly letters between Philip Yorke, son of Lord Chancellor Hardwick, and the editor-historian Thomas Birch; the exchanges spanning an even longer period, from the late 1730s to 1770, between Yorke’s wife Jemima, the Marchioness Grey, and her childhood friend Catherine Talbot; and the extensive corresponding networks of Elizabeth Montagu, the Bluestocking hostess introduced in Section 2, with family members, female and male Bluestocking friends, literary figures, and business contacts, extending through almost seven decades up to 1799. Despite their shared longevity, these correspondences differ in the social dynamics between their participants, the functions performed by the ensemble of exchanges, and their literary historical significance. They also vary in their preservation histories, from their first creation to the present. It is with questions of preservation that this section begins.

3.1 The Materiality of Correspondences

In any study of a correspondence, it is necessary to distinguish between its ideal form – that is, the complete set of exchanges between two or more individuals, which generally exists only in theory – and the actual materials that have survived. Surviving documents may be drafts or retained copies; sent letters might have miscarried before reaching their intended recipient. Letters safely delivered might subsequently be damaged, lost, or destroyed. While correspondences were rarely published as printed books in their authors’ lifetimes,Footnote 40 many were preserved by their writers and/or recipients in manuscript form, often bundled, sewn, or bound together according to correspondent. Such collecting practices indicate the value placed upon the familiar letter, especially as part of an extended epistolary exchange. These practices also were the first determiners of what is available to us today, and in what form. Any study of correspondence, like other manuscript studies, must therefore consider the peculiar vicissitudes to which a series of discrete documents produced over many years and in various locations may be subject.

Since temporal gaps are inherent in correspondence as a medium, its twenty-first-century reader must interpret whether such gaps in the record mean nothing at all, simply registering through silence a period when the correspondents were within reach of regular conversation, or whether they signal a rupture in the social bond or the destruction or loss of materials sometime in the afterlife of the exchange. As an example of the former, the Yorke-Birch letters are carefully bound into folio volumes as a complete set, yet they exhibit annual gaps when both men were resident in London. With the Montagu correspondence, on the other hand, letters from the sensitive 1751–52 period in which Elizabeth’s sister Sarah was forcibly separated by her family from her husband George Lewis Scott have disappeared, likely deliberately destroyed in an attempt to preserve family secrets. Most of Talbot’s letters to Grey are believed to have been accidentally discarded in the process of sorting Grey’s papers after her death.Footnote 41 Thus, a correspondence in manuscript may survive in any number of states, from a one-sided fragment to a set of bound volumes entirely recopied in the uniform hand of a descendant.

In the Montagu case, many of the original manuscripts were preserved, embellished with her nephew and heir Matthew Montagu’s editorial markings (and later, those of other editors). This allows for a comparison of the manuscript record with the four-volume selection published by Matthew between 1810 and 1813, revealing perspectives and methodologies very different from those of today’s scholarly editor. The print edition of the letters, for example, almost entirely omits the greetings and miscellaneous items typically conveyed in the final paragraphs and postscripts of a letter – precisely those details from which a researcher might reconstruct patterns of book borrowing, for example, or the vectors of a network. This was common editorial practice for the period, but Matthew Montagu also expunges much of Elizabeth’s sharp-tongued, colloquial commentary as well as details that highlight her dependent status as a companion to the Duchess of Portland – for example, her view of the clergyman Edward Young’s satire of women (“for those Animals he has ridiculed it is not a farthing matter for them”) disappears, while her being “invited along to Lady North’s” to see the formal court dress of an assembled group of courtiers, becomes simply “I was at Lady North’s.”Footnote 42 Such alterations underscore the principle that best scholarly practice requires consultation of the physical manuscripts that comprise a correspondence, as opposed to later printings, when those exist.

Even when manuscripts survive, methods of preserving and cataloging can vary significantly, raising barriers to navigation and interpretation. Correspondent and/or date are the most common organizational systems but in vast assemblages such as the 6,923-piece Montagu Collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino California, even such logics leave difficulties. In that collection, the combination of numbering the individual letters in different sequences for each correspondent but then storing the entire collection in a chronologically ordered series of boxes, with no master inventory cross-referencing this information or documenting contents, for many years resulted in an archive searchable only by trial and error as to exactly how the letters of a particular correspondence might be distributed across the 117 boxes of the collection. (A 2015 finding aid available through the Online Archive of California has at last mitigated this.)Footnote 43 In a comparable case, that of the Forster Collection of Samuel Richardson’s correspondence held in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, six massive folio volumes created in the late nineteenth century are generally organized around discussion of the three Richardson novels, preserving the author’s own mode of compilation.Footnote 44 The result is a collection that is not only extremely unwieldy, with quarto-sized letter paper glued at ninety-degree angles into two openings per page, but very challenging to search by correspondent or date in the absence of individual item labels (Figure 12).

Figure 12 [Arabella Churchill] to [Jane Collier], 30 June 1749, FM XV, 2, f. 22 in the Forster collection at the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrating the insertion of letters at a ninety-degree angle to the page opening.

As these two instances demonstrate, and as Section 5 will explore in greater detail, to study a correspondence in manuscript is to work through layers of physical and interpretive mediation even when a large proportion of its surviving components have been kept together. Almost always, some documents have found their way into archives on different continents: approximately one-quarter of the Montagu letters, for example, are held in locations other than the Huntington, and more are being found on a regular basis.

Current digitization projects address some of these issues by reuniting letters in a virtual space, preserving fragile documents and offering searchable access to researchers for whom archival examination is not possible. As unique collections are digitized, it also becomes feasible to take a more holistic approach to them as extended, collaborative texts. The Montagu correspondence is currently being digitized and edited as the Elizabeth Montagu Correspondence Online, an open-access undertaking by a large, international team of scholars, supported by a substantial charitable trust as well as numerous institutions and research organizations;Footnote 45 this edition will enable the kind of comprehensive tracking of persons and subjects through the correspondence that has never before been possible. At the same time, digital remediations, like print editions, can flatten the complexity of letters as three-dimensional objects that bear witness to their history of folding, sealing, posting, docketing, bundling, and editing. The question of digital remediation is taken up in greater detail in Section 5 of this Element; this section will focus rather on what makes these variously imperfect collections worthy of study, that is, on the insights they can yield into eighteenth-century lives lived in the Republic of Letters. In their individuality, even imperfectly preserved correspondences allow us to trace social authorship at work as familiar letters are composed and exchanged.

3.2 “Laudable Ardor”: Philip Yorke and Thomas Birch

Held in the British Library as part of the Hardwicke Collection, the twenty-five-year weekly correspondence between Philip Yorke (1720–90), heir to the powerful Lord Chancellor Hardwicke, and Thomas Birch (1705–66), urban, middle-class clergyman, editor, and author, is preserved in a complete chronological sequence, carefully bound into five folio volumes. Although Birch, like Yorke, bequeathed to the British Museum (now the British Library) his voluminous historical papers and correspondence, the materials were not organized systematically as complete two-sided exchanges by Birch himself before his unexpected death. This sequence of weekly letters is an exception in its continuity and completeness, including Yorke’s own contributions, which were likely returned to him by Birch’s literary executor when the latter’s death ended the exchange (Figure 13). This completeness is not simply the product of posthumous chance: the correspondence was viewed from the start as a work of periodical literary history, one that would both inform and entertain. It was therefore treated by both men in keeping with their shared historical aims. For today’s reader, the cumulative sequence offers not only such a text but also the history of a personal relationship that cuts across traditional social boundaries to resemble a modern friendship.Footnote 46

Figure 13 Two openings from folio volumes in the Hardwicke-Birch correspondence in the British Library: the first image is of BL Add MS 35396, f. 24, the address page of Yorke to Birch, 20 Sept. 1741 (quoted later), with Birch’s subsequent letter just visible behind; the second image is of Yorke to Birch, 28 May 1752, BL Add MS 35398, f. 45 (quoted later), again with Birch’s next letter appearing behind.

The Yorke-Birch correspondence demonstrates how a hierarchically organized social relationship could be transformed into a more egalitarian one through shared literary-historical endeavors in the Republic of Letters, as well as how the familiar letter itself was practiced and appreciated as a literary form. When Yorke married Jemima Campbell (1722–97), granddaughter and heiress to the Duke of Kent, in 1740, he left Cambridge and soon was based largely at the country estate of Wrest in Bedfordshire. In collaboration with a coterie consisting of his brother Charles; Cambridge friends and tutors; and Catherine Talbot, his wife’s lifelong friend, he pursued his literary-historical interests by producing a collection of pseudo-classical epistles, Athenian Letters, or the Epistolary Correspondence of an Agent of the King of Persia, between 1741 and 1743. Birch, who had been granted a clerical living by Yorke’s father, was engaged to see through the London press a private edition of about a dozen copies. This transaction evolved into an engagement on Birch’s part to send a weekly epistolary account of London literary (and political) news to Yorke during the seasons when the latter was in the country; the ensuing dialogue ended only with Birch’s death in 1766.

Thus rooted in a patron-client relation, these letters are viewed by Markman Ellis as reflecting the seventeenth-century secretary’s role, with “its mixture of trust, service and friendship”;Footnote 47 indeed, we see them becoming the foundation of a friendship in the modern sense of a relationship characterized by egalitarian exchange, compatibility of interests, and companionship. While scholars have generally focused on the letters as a source of literary gossip, Yorke praises Birch as a gifted practitioner of the familiar letter genre. Rather than writing as a mere formality, “with you it is a relaxing of the mind in the most ingenuous way, communicating the fruits of one’s studies, & speculations & repairing the loss of a Friends good Company in the most effectual manner.” Birch in turn acknowledges that one dimension of Yorke’s friendship is the prestige it brings (it is “a Friendship, which I feel the influence of in the kind Opinion entertain’d of me by others”), but he values it not only as “the Ornament” but also as “the Happiness of my Life.” For Yorke, the unexpected death of Birch after a fall from his horse in January 1766 is marked as “a day I will always remember with grief, and will always honour.”Footnote 48

Both men show awareness of the correspondence as a cumulative text with its own structural logic, governing metaphors, and conventions. Thus Birch opens the annual cycle on June 29, 1751, upon Yorke’s return from London to Wrest, with a self-conscious flourish:

At the Entrance of the Eleventh Year of my Correspondences, the only Preface I shall use is the well known Observation, that quiet Times, tho’ the best to live in, are most unfriendly to the Writer of them. But I have so great a Regard for the Peace of the World, that I shall be more contented to have my Letters neglected for their Emptiness or Insignificance, than to have the Occasions of filling them with Events … arising from the Misery & Devastation of the Nations, … I hope to see no other Wars, than of the Republic of Letters, a State, which is never like to enjoy a thorough Tranquillity, while the Appetite for Fame or Bread urges its Members to constant Hostilities.

A year later Yorke attests to the value of this chronicle of the Republic of Letters as retrospective entertainment: “I believe few Correspondences have been more regular & uninterrupted than ours since It began; your part of it already swells into a second Vol: & the First is produced as a choice Treat to any particular Friend, & during the present rainy fit of the Weather is the principal Study of my Brother Jem.”Footnote 49

Although Yorke remained the aristocratic amateur and Birch the energetic professional, there was clearly something in the former’s function as reliable cheerleader (“Let me raise the dying flame before It quite expires, … Is application necessary I will second it; Is Money wanting I will advance it, Is the Labor of Eyes demanded, I will at least share with You ye glorious Toil”) that affirmed the value of Birch’s labors. Above all, the two men shared what Yorke facetiously calls a “laudable Ardor for old Sacks, bad Hands, & dusty Bundles.” Markman Ellis has described the pair’s Whig historiography in general as driven by a “[high] regard for primary evidence,” expressed in their “archival recovery of the correspondence of the officers of the state, secret service intelligence, small pamphlets and satires, and newsbooks and newspapers,” used not only in their own research but also edited and published by them.Footnote 50 Dedication to documentary research also led to their working in tandem on such influential projects as the revival of the Royal Society (to which Yorke was elected in 1741 and for which Birch was secretary, 1752–65) and the establishment of the British Museum (Yorke chaired the parliamentary committee behind its founding, and both men served as trustees).

The significant socioeconomic gulf bridged by this productive collaboration is illustrated on one occasion when Yorke suggests that Birch is being taken advantage of by his publisher Andrew Millar and naively asserts that if his forthcoming edition of The Memoirs of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth (published 1754) were to be puffed properly, it would sell as well as a Henry Fielding or Charlotte Lennox novel. Birch’s response is uncharacteristically testy: