Preface

This story begins in a rather unexpected place, with an unlikely figure for a study of women and the art of letterpress printing. Robertson Davies was a Canadian novelist and the first Master of Massey College in Toronto, Canada. A gruff old fellow with a formidable beard, he was a celebrated writer and by all accounts a hilarious storyteller – but he was no feminist. For the first nine years of his time as the Master of Massey College (1963–81), in fact, the institution only admitted men.Footnote 1 He acquired printing presses for the college, with the intention that the students might use them to print their own writings, and so were born the ‘Quadrats’Footnote 2 – a group of professional typographers, printers, and bibliophiles who built a small society and an impressive collection of printing materials, ephemera, and antique equipment.Footnote 3 It was in this space, called The Bibliography Room, where I first learned how to print, in 2008, alongside other novice printers – mostly women.Footnote 4 I spent nearly every Thursday afternoon during the five years of my PhD programme in an informal apprenticeshipFootnote 5 learning how to set metal type, how to clean and preserve wood type, how to sort spacing by size, how to produce prints on a variety of different nineteenth-century cast-iron hand presses, and how to tell the stories of those presses for interested passers-by. Mostly, I made ephemeral prints such as bookmarks and event keepsakes and quartos for use in book history graduate seminars.

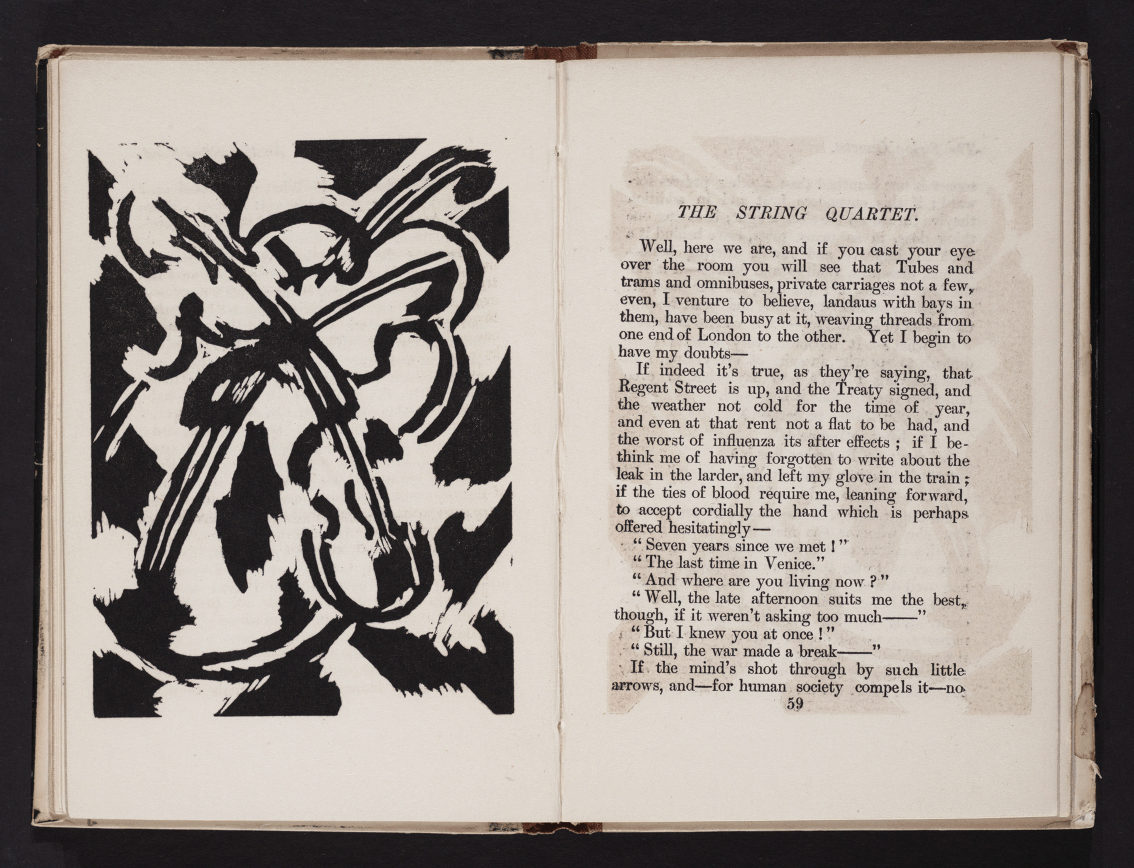

While I was never a part of the inner circle of ‘Quadrats’ at Massey, I accessed that space as a female student working on Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, open to learning and unaware at the time of the long history and bounded nature of print shops as gendered enclosures. My own interest in Hogarth Press stemmed initially from the hypothesis, also advanced by Hermione Lee, Alice Staveley, and others, that the rhythms and processes of letterpress printing were connected, for Woolf, to her writing.Footnote 6 Following Woolf in the 1920s and 1930s, other modernist women writers also took up letterpress printing, notably Nancy Cunard and Laura Riding,Footnote 7 and in this Element I aim to enrich some of the context around and extend the narrative from Woolf: through the trade structures that excluded women writers to the other modernist women who also printed and then through to the present moment and to the afterlife of the modernist independent press in contemporary letterpress projects by women.

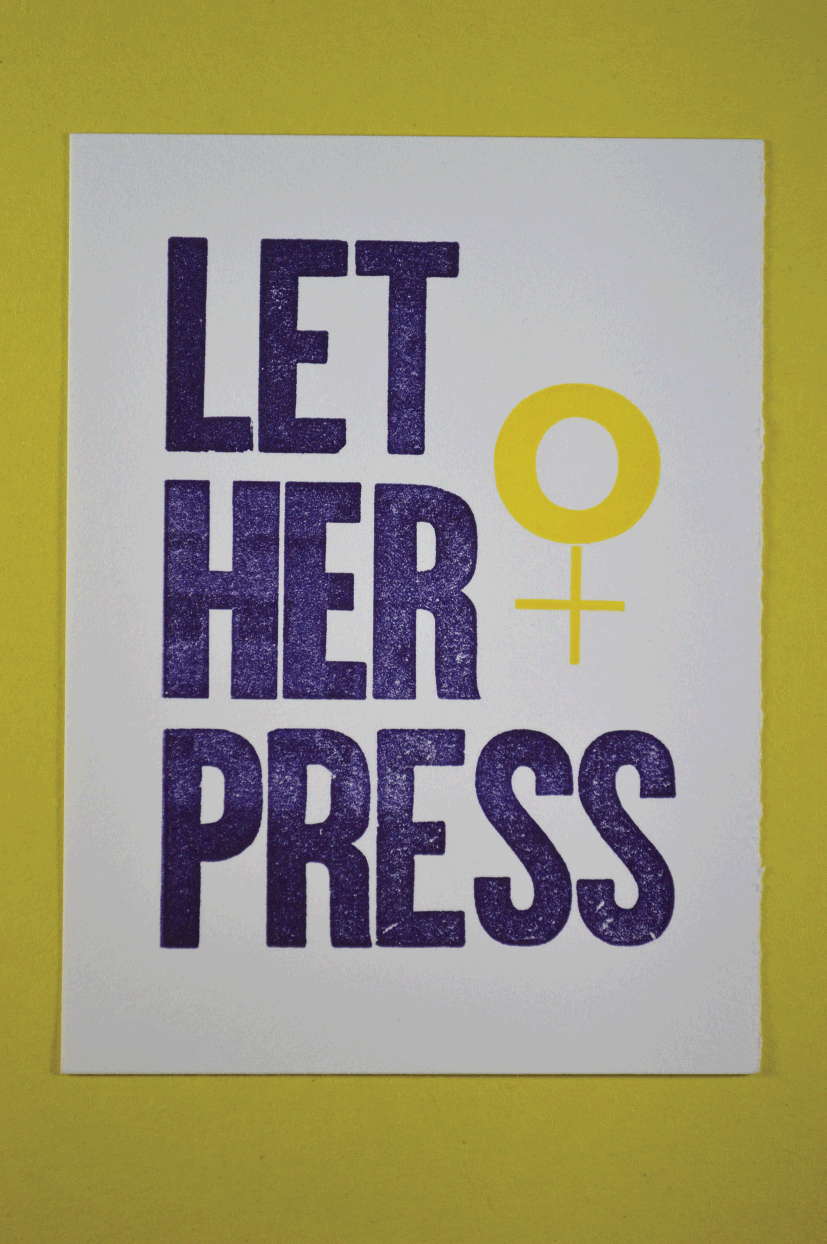

I recognize here that Woolf is a privileged exception in the world of printing, as I am: quite a lot of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century print history is predicated on the assumption that the writer and the printer would be separate individuals with separate jobs to do. The purpose of trade printing was not the same as acts of printing undertaken by artists or by students. As an apprentice at Massey, however, I had academic, creative, and historical intentions simultaneously. I wanted to learn how to print in part because I thought it might help me think differently about how Woolf wrote but also about how I might write. In learning to set type and to print, I explored the malleable relationship between language, tactility, and time. I therefore, like Johanna Drucker,Footnote 8 take as fundamental the idea that letterpress printing is a literary art and an art of textuality. That there is a relationship between the intellectual contents being printed and the act of printing itself, and that this relationship is even more intimate when the writing and the printing are done by the same individual or small collaborative group, seems essential in understanding the value of printing as a form of expression undertaken by women writers, activists, and artists in the twentieth and twenty-first-centuries. The lay of the type case, the sound of the ink on rollers, the sensory and embodied experiences of print, all of these are pleasures and processes that matter to writers who print. The words on the page also matter enough to the writers who produce them that they demand the care, attention, and time required by the slow art of letterpress. Figure 1 is an example of a keepsake produced by Elisa Tersigni, at the time one of the student apprentices in The Bibliography Room, as a commentary on the gendered nature of printing.

Figure 1 ‘Let Her Press’ printed in the Massey College Bibliography Room by Elisa Tersigni.

In what follows, I will lay out what I see as some of the contours of the rich history of women and letterpress printing in Canada, the United States, and the UK, through the twentieth century and up to 2020. I propose here a number of ways of thinking interdisciplinarily and theoretically about the historiography of women and printing. Throughout, I take an integrative approach, pulling materials from design history, printing history, book history, literary studies, creative writing studies, feminist historiography, and interdisciplinary craft studies.

This Element is organized in four sections. In Section 1, I begin with a methodological reflection on the existing critical discourse on women and printing, an analysis of some of the particular considerations of letterpress’s role in a contemporary era, and a reflection on why practitioners might choose this technology now. I continue in Section 2 with an analysis of some of the modes of discourse and training through which women have learned the craft of printing. In this section, I also offer a brief description of the process of letterpress printing itself and its associated terminology, which I read for its gendered linguistic associations. In Section 3, I discuss short vignettes focusing on particular examples of women engaged in acts of printing as representations of gendered labour. Section 4 focusses on printers’ own written reflections about letterpress and particularly about the relationship that author-printers see between their role as authors and the act of printing.

1 Historicizing

The critical history of women in printing is rich but also rather diffuse. It crosses work in a variety of disciplines: graphic design history, literary studies, book history, labour and political history, and women and gender studies. There are many fascinating individual case studies of societies and collectives, particularly in the period just preceding the one I consider here, such as the Women’s Printing Society, the Cuala Press,Footnote 9 and the Victoria Press.Footnote 10 Often these studies isolate a component of the story: the social structures of trade unions, the mechanics of printing, or a literary analysis of the works on the page. In this Element, I draw from all of these different disciplinary foundations in order to form a method for analysing the ways in which form and craft – as polysemic constructs that cross the boundary between materiality and textuality – can encourage holistic thinking about women and print without oversimplifying a complex and diverse set of individual examples. In this section, I offer an interdisciplinary approach to women and printing that considers the topic from a variety of perspectives.

1.1 Formes and Forms

The focus of this Element is, in one sense, rigorously specific: I write here primarily about letterpress printing and not about other mechanisms by which prints and books can be or have been made in the last 100 years. I do not write here about zines made using photocopiers or mimeographs, about mass-produced artefacts, about textual embroidery samplers, or about calligraphy, although all of these are fascinating textual media with growing critical literatures, and many of the questions provoked by letterpress printing might equally apply to bookmaking using other methods.Footnote 11 I am interested specifically in understanding what is distinctive about letterpress in a time when transferring text in multiple copies onto paper is extremely fast with the use of digital printing and, in some cases, no longer even necessary at all since we frequently now do our reading on screens. To borrow a term more commonly used for newer technologies and in design theory, what are the precise ‘affordances’ of letterpress for literature during this period of time, and how might those affordances relate to the tangled histories of feminism, aesthetics, and labour in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries? In order to unpack these various affordances, my specific examples here focus primarily on relatively small operations and the work of a small subgroup of letterpress artists I define, particularly in Section 4, as literary printers.

In her influential book, Forms (2015), Caroline Levine begins with a challenge to the critical orthodoxy that a literary critic doing her job ought to ‘keep her formalism and her historicism analytically separate’.Footnote 12 Instead, Levine posits a framework in which ‘forms are at work everywhere’Footnote 13 and advocates for a more capacious analysis of social and political structures, literary structures, and material structures all as forms deserving of formalist attention. The idea of form itself has been at the heart of literary critical crises of disciplinary self-representation throughout the period of time I cover in this Element. Formalism’s rise in the early twentieth century – via the New Critics such as Eliot and Empson and the Russian Formalists – was initially concerned with the analysis of literary texts on their own terms, stripped of easy explanatory contextual meanings and analysable through close attention to linguistic particulars. Formalism in this sense does not, in most cases, admit the possibility or relevance of material form into the discussion. The ‘form’ of a poem generally would be more likely to refer to its categorization as sonnet rather than the fact that the body text of the edition under consideration is set in 12pt Caslon type. Yet material form and literary form in the cases I discuss in this Element are aligned and allied. Johanna Drucker’s study of early twentieth-century experimental typography argues forcefully that ‘it is in material that the activity of signification is produced’,Footnote 14 and not only in works that exploit deliberately disruptive or innovative typographical practices. A consideration of all elements of form, literary, linguistic, material, and historical, is merited in a study of textual artefacts and the processes and practices that produced them. The idea of form also finds a material and literal meaning in the printing world in the object of the ‘forme’, the ready-to-print object: a metal frame (a chase) in which the page layout including type, illustrations, and spacing is locked. A forme is a bounded and constrained space in which almost infinite possibilities have been locked up and are ready to print, including all of the various possibilities of literary form. Many letterpress artists, as I will discuss in Section 3, are thinking about both form and forme as they produce their work: they’re thinking about language, rhythm, and metaphor just as they are about line length, justification, and paper type.

In my frame of reference, letterpress is primarily an artist’s, activist’s, or writer’s medium, as opposed to an instrumental or commercial technology. However, understanding the structural history of labour in printing is crucial to understanding subsequent constructions of gender in twentieth-century print. I therefore address industrial trade history here, particularly in Section 2, in order to demonstrate the forms of exclusionary practices in print shops that inform the work and the experiences of later artists. There is, however, for most of the printers I write about here, significant self-awareness and conscious adoption of this medium for specifically artistic, political, or literary purposes.

1.2 Forming a Critical Discourse

Although letterpress printing has its own specific history, new work on this subject must, of course, be situated in relation to the broader critical debates about gender in book history. In a 2020 roundtable hosted by the Bibliographical Society of America entitled ‘Building Better Book Feminisms’, Leslie Howsam looked back at her 1998 article in SHARP News, ‘In My View: Women and Book History’. In writing that piece, she intended to begin a conversation in the field about the fact that, although book history as a whole tends either to be treated as a genderless, object-oriented space or to default to masculinity, ‘women can be identified at every node in the cycle and at all periods in history’.Footnote 15 While the work of feminist recovery has highlighted specific women involved in the production of books – from widows managing printing operations after their husband’s death to feminist collectives running publication initiatives specifically aimed at female readerships – Howsam noted that the methodological structure of book history could hardly be considered feminist.Footnote 16 Reflecting on this piece twenty-two years later, Howsam remarked that she had hoped it would be the first in a great number of feminist book historical ventures and that it would spark a lively conversation in our field.Footnote 17 And so she waited … and waited. In spite of Howsam’s call to bring women’s labour and practice more to the fore in book history discussions, Kate Ozment, writing in 2019, persuasively delineates the ways in which ‘the history of the book is still largely defined as a male homosocial environment where female figures are briefly mentioned on the margins of textual production or invisible altogether’.Footnote 18 In spite of the rich tradition of work on women and print on which I build here, there is clearly still more to be done, particularly on the matter of how we theorize gender in book history.

A practice of feminist book history scholarship depends on an explicitly and generously citational ethos that acknowledges lineages of discourse both within and outside the field. As Ozment points out, however, the establishment of canonical and overly rigid critical and methodological approaches can be just as limiting in practice as relying on a small selection of frequently repeated case studies and examples. If we continue to rely too heavily on Robert Darnton’s models and examples for book history – which was never his intent in any case in creating them – we risk missing what might exist outside or beyond or even deeper within Darnton’s ‘communications circuit’ and lose some of the sociological structures and nuances that underlie each of the different components of the model itself.Footnote 19 Part of the reason for my granular focus in this Element on letterpress printing specifically, and even on a particular kind of letterpress printer, is to isolate a component of book historical production that has its own complex and specific history of gendered labour practices and subsequent artistic refashionings. Part of what I seek to do in this Element is to suggest – as Alice Staveley put it, recontextualizing for book history Gertrude Stein’s phrase that there ‘is a there there’ – that the broader subject of women and letterpress is one we can treat with the same analytical force as we do the purportedly genderless or object-oriented history of print.Footnote 20 The metaphor of the constellation might serve us as feminist historians here: we can apprehend patterns and images even as we acknowledge the limited nature of our own perspectives.

The gender dynamics of the book trade at large are, as has been amply documented, more nuanced and diverse than the specific history of women and letterpress.Footnote 21 Unlike bookbinding, which has a long, rich history of women’s participation;Footnote 22 unlike editorial and secretarial work, which was historically (and often invisibly) done by women (particularly as the industry began to be ‘feminized’ through the nineteenth century, as Sarah Lubelski has shown in her excellent study of Bentley’s);Footnote 23 unlike the ‘feminizing’ of typesetting in the photocomposition era, when it could be done at a keyboard;Footnote 24 when the physical work of operating a printing press was a foundational part of the commercial trade, women could run the feeding station of a steam press but not actually operate it. J. A. Stein argues that printing and specifically the role of the press machinist continued into the 1980s to call up a specific association with ‘masculine craft identities’.Footnote 25 Even as offset lithography began to take over in the trade, there was a further retrenchment of gendered roles, including ‘a masculine embodiment that was attuned to and shaped by the materiality and aesthetics of printing technologies’.Footnote 26 Stein further notes that the continuation of this gendered dynamic in the print industry after the commercial decline of letterpress points to the fact that these masculine associations were not tied specifically to letterpress traditions but were related to ‘other dimensions of technology, such as aesthetics, design, embodied “know-how” and the physical presence of large-scale machinery on the shop floor’.Footnote 27 I would like to define and interrogate the gendered resistance culture that arises in letterpress communities of the twentieth century and, particularly with the rise of online communities, into the twenty-first. What does it look like to take a craft with a history of masculine professional identities and make it feminist or feminine or non-binary? What does it mean, moreover, to make it into a frequently and deliberately amateur undertaking – something you learn not necessarily through a formal apprenticeship or a trade school but through old manuals scavenged from used book sales or borrowed from libraries, from friends in your own little studio, or simply through trial and error?

1.3 Constellated Historiography

Print feminisms, perhaps unsurprisingly, follow the broad strokes of the history of feminism through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first: from the first wave of suffragettes using letterpress to make posters and pamphletsFootnote 28 through to the present day of interrogating what narratives of predominantly white women’s history can mean for intersectional constructions of genderFootnote 29 that unravel hegemonic categories. As the labour structures around women’s participation changed through the course of the century, so too did the content of the prints, reflecting the feminisms of the moment.

Part of what I intend to do in this Element is to intervene methodologically in the field by considering how and why we might approach the study of women printers in a constellated rather than a comprehensive fashion. I focus here on some very bright stars and some less visible ones, and some patterns and implications arise from seeing them together, but I make no attempt here to suggest that I’m showing the whole firmament. The figure of the constellation has helped me to think about the extremely challenging process of example selection in a time period that is so full, so diverse, and so complex that drawing out particular examples almost inevitably feels either overdetermined by existing canons of print culture or feminist history or else completely random. Thinking about feminist historiography as a constellated practice allows patterns and suggestions of meaning to come into and fall out of view; it suggests that some kind of narrative is possible but that comprehensiveness is not the goal. I also hope to offer a method in which other views of the field are not only possible but explicitly welcome. I hope readers will consider this Element an enthusiastic invitation to future work in this area, particularly in contexts outside Britain and North America.

Rather than providing a comprehensive collection of women who print using letterpress in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, I instead gather a constellation of examples in order to suggest what it might mean more broadly for the historical masculinities of letterpress printing culture to encounter non-dominant gendered experiences. The inevitable gaps and silences in this Element are due in part to the uneven nature of research on printing history and particularly on the aspects that go beyond the actual printed documents themselves to consider questions of labour and affective experience. In the secondary literature on women and print, noting the fragmentary nature of the archival record is something of a critical commonplace. Dianne L. Roman describes the sources on pre-nineteenth-century American women in print as ‘unruly, tangled, and for some, nonexistent’.Footnote 30 Roman also points out that even existing well-known resources, such as Lois Rather’s Women As Printers (1970) are not always consistent or accurate, and materials are often gathered from a variety of sometimes unlikely places and pieced together. Maryam Fanni, Matilda Flodmark, and Sara Kaaman favour the term ‘messy history’, coined by the graphic designer Martha Schofield, to describe their gathering of historical documents and essays on the history of women in graphic design. They describe their materials as a ‘collage of images’,Footnote 31 another helpful aesthetic figure for thinking about feminist historiography as a citational and yet non-comprehensive practice. The challenges of collecting thorough resources have led to a frequent practice, too, of list and bibliography making. In 1983, Barb Wieser of the Iowa City Women’s Press compiled a directory of women printers and typesetters but was careful to emphasize that it was ‘only a partial listing’.Footnote 32 Cait Coker and Kate Ozment’s ‘Women in Book History Bibliography’ and the Alphabettes bibliography of women in typeFootnote 33 follow similar impulses to collect and continually expand the range of reference for this discipline. The narrative threads in this Element are necessarily and deliberately fragile, in keeping with feminist traditions of form and narration that argue against teleological or developmental historical narratives and in favour of instances of resonance within the historical record that can illuminate their surroundings without overdetermining the story.

Part of the reason for the fragility of these many distributed archives of print history and for the fragmented components of the historical record is that, while it is most often straightforward to find out directly from a printed object or from a library catalogue which publisher or press printed a book, it is much more difficult to be precise about who did the actual printing, and even less straightforward to establish or discern the gender identity of that person. Elis Ing and Lauren Williams are currently investigating the work of women printers in McGill Library’s Special Collections, and one of their search techniques has been to look for the words ‘veuve’ or ‘widow’; prior to the twentieth century, it was common for women to have their printing work in family firms acknowledged only after their husbands had died.Footnote 34 For the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, such a search would prove less fruitful, since a much wider array of women and non-binary and gender-nonconforming people now engage in printing practices. Since many women were, for reasons I will discuss in Section 2, often not historically members of official trade unions, sometimes there is very little or no documentation of their employment or their printing output.

The constellation as a spatial figure assumes gaps between luminous points, but those spaces always offer the possibility of future discovery. The printers I do feature here, particularly those in Section 4, connected to a feminist British literary modernist tradition originating with Virginia Woolf, skew affluent, white, literary or artistic, and well-connected. They are some of the people who left substantive documentary evidence of their labour and their process and whose work speaks to one another, and it is worth acknowledging that there were many more women – and, notably, women of colour – working as letterpress printers in this time period. Many will have left very little trace beyond the books they printed, many of which would not have borne even their names.Footnote 35 It is partly because of the collaborative nature of textual production that historical evidence of these experiences is difficult to come by: printers don’t always (or even often) write about printing, neither do they always (or even often) appear in photographs. As Christine Moog notes, writing about some of the earliest women working in the book trade, ‘roles that women in the industry have played have largely been ignored – in part due to lack of archival material and in part due to the fact that when women produced printed pieces, they often either did not attribute their names to their work or instead credited themselves as “heirs of a master printer”’.Footnote 36 Writing in 1981 for the journal Library Review, the printer Jean Engel urged women’s studies scholars to take notice of women printers in spite of the dispersed and sometimes unconventional nature of the materials they were producing: ‘We need librarians to be aware of the existence and importance of woman-produced materials, even though they don’t fit the norm. We need women’s studies faculty to be aware of the publishing and printing origins of the texts they use and of their own options in feminist publishing.’Footnote 37 Institutional collections definitely contain women’s materials, but it is also crucial in the history of printing more generally to consider alternative spaces that might house some otherwise uncollected materials. The contemporary poet and printer Lauren Elle DeGaine, writing of her historical work on women type designers, proposes internet auction sites as other important repositories for research:

The ‘eBay archive’ allows women’s work to be recovered from the margins and provides a piece of the story of the role of women in design, print culture, and book history. Such commercial sites comprise a kind of extra-institutional international finding aid that has become an important scholarly mechanism for recovering research material currently missing from institutional archives. At the same time, it also highlights the instability of material culture traded in the open market.Footnote 38

Engel’s call for preservation of textual forms that might not always make it into conventional collections aligns with Alan Galey’s work on what he calls ‘pro-am’ or pro-amateur online archives.Footnote 39 Printing historians, particularly those who once worked in the trade, are avid collectors and cataloguers, particularly of historical equipment. These digital spaces are often sites of memory and collection that contain tremendously rich detail unavailable elsewhere. DeGaine’s emphasis on seeking out and locating unconventional sources for historical materials shows that part of the way in which we can ensure preservation of these stories is by writing and thinking about them even in the absence of a robust or coherent institutionalized historical record. For research on contemporary letterpress practitioners, web communities, the Instagram archive, and the TikTok archive are particularly vital.Footnote 40

1.4 The Embodied Language of Print

I began with the personal story of my own entry into letterpress printing because, as an embodied cognitive experience, typesetting and printing are practices that you need to physically do in order to learn. By undertaking the print process by hand, you learn the language and the nuances of what it means to press type into paper and thereby make an impression. As Sarah Werner argues, there is no escaping gender, even in the seemingly object-oriented world of bibliography: ‘If I’m only interested in the mechanics of printing, need I think about gender at all?’ Werner asks; ‘Well, yes, always yes, but especially yes in Renaissance England, where the word “press” was a term that could be used both to refer to printing but also to a physical pressing of a man into a woman, that is, an act of sexual penetration and deflowering.’Footnote 41 Wendy Wall points to the ‘bawdy’ implications of the phrase ‘undergo a pressing’, which in Elizabethan drama referred to ‘act[ing] the lady’s part’, giving rise to what Wall describes as the many ‘contradictions and slippages’Footnote 42 inherent in the gendered language of print. The etymological layering of ‘press’ is just one example of printing terminology as a language of the body. We speak of type ‘faces’, and the anatomy of a sort is itself a gendered one: it has a body, a shoulder, feet, and a beard.Footnote 43

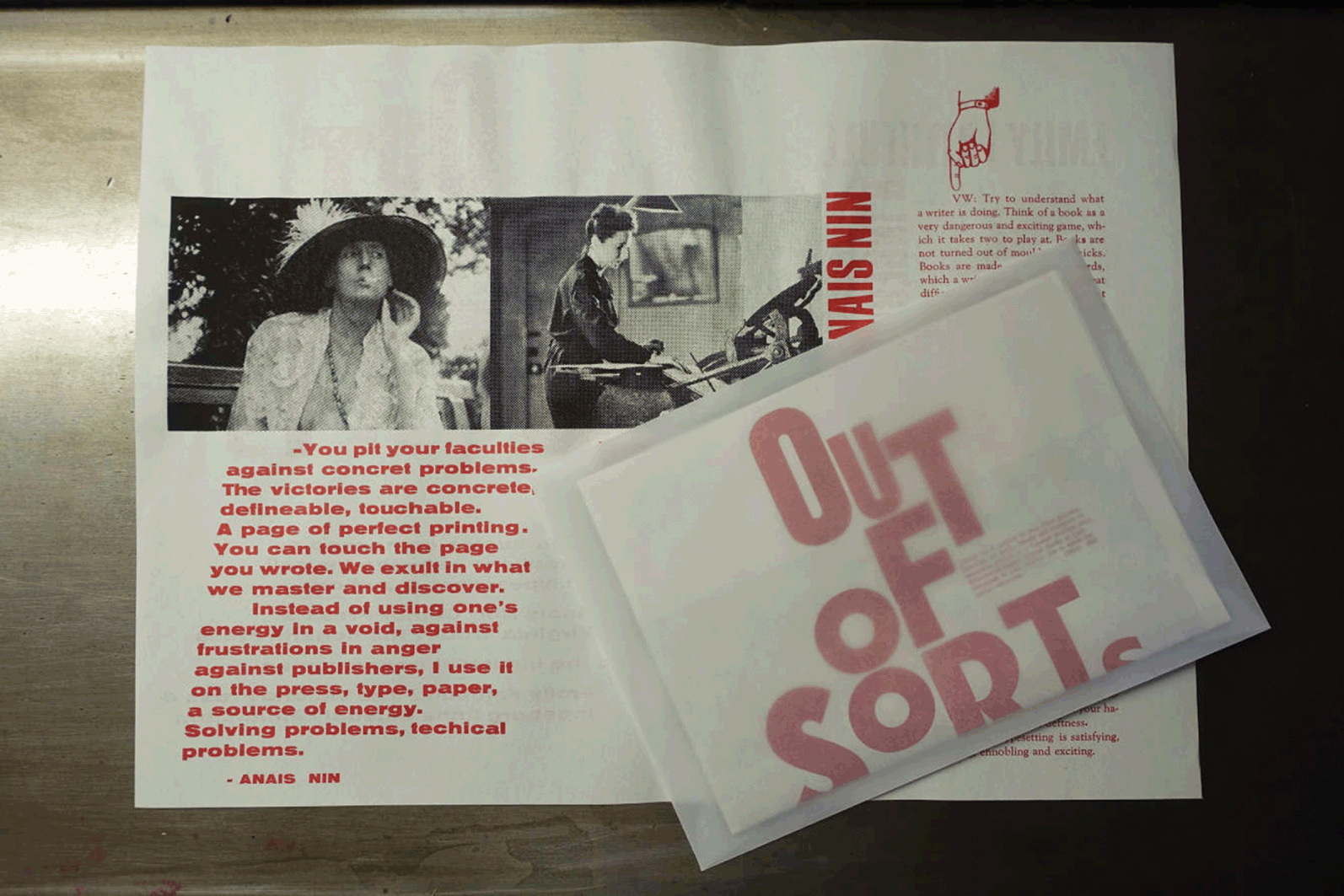

Printing is a discipline rife with puns. The bodily language of typography suggests multiple layers of meaning and interpretation, even if many of the literal origins of printing terms and expressions we now use have become dead metaphors. The affective valences of printing words and phrases often reveal themselves when the terms are reconnected to their printing origins. ‘Out of sorts’ in printing refers to the heart-stopping moment of setting a job and realizing you haven’t enough letters (sorts) left in your case to say what you mean; uppercase and lowercase letters have their origins in the spatial positioning of type cases; and ‘mind your p’s and q’s’ (that general phrase exhorting people to fastidiousness) is in printing an expression that refers to the easy confusion for printers between these two sorts. I include a Glossary of printing terminology (indicated in bold) at the end of this Element in part to orient the reader and ensure that the specialist terminology itself is not used in an exclusionary fashion but in part also to foreground myriad ways in which the language of print is multivalent and slips easily into a layered historical discourse.

The matter of printing language also raises aesthetic questions. One specific way of tracing the shift in the nature of letterpress through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first is to follow its shifting material aesthetic. The varying depths of impression that type can make in paper are called ‘bite’ (deep) and ‘kiss’ (light) impressions. It is impossible not to see the embodied implications of these terms, describing an encounter between paper and type in a language of intimate physical exchange. Letterpress printing that kisses the paper just lightly enough to produce an even impression was, until recently, considered the most skilful and pleasing outcome; this way there was no indent visible on the back of the page, so double-sided printing could occur without obscuring any text.

Other methods of printing, such as digital and offset methods, do not produce this bite at all, and so it has become a kind of aesthetic shorthand for a material experience that announces its connections to the past, even though historically printers were trying to be ‘kissers’ rather than ‘biters’. As the printer Amelia Hugill-Fontanel notes, William Morris had an influence in bringing ‘bite’ impressions into favour among fine printers in the nineteenth century, and ever since ‘it’s been traditionally understood that the kissers were commercial and the biters were fine printers’.Footnote 44 In the twenty-first century, the ‘bite’ of letterpress is what indicates a certain authenticity, regardless of the type of print being produced. Musing on the modern popularity of the bite impression, the printer and founder of Ladies of Letterpress, Kseniya Thomas, speculates on the possibility of the bite coming into popularity because of the shift towards a more amateur print culture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: ‘I almost wonder if the deep impression we associate with letterpress today came about when people without printing backgrounds came to letterpress, pulled their first print on their old press, and realized that the default setting – a palpable impression – was beautiful.’Footnote 45 The foregrounding and prevalence of bite impressions highlight materiality and emphasize a ‘printishness’ akin to Jessica Pressman’s concept of the distinctly twentieth- and twenty-first-century phenomenon of ‘bookishness’: ‘a creative movement invested in exploring and demonstrating love for the book as symbol, as art form, and as artefact’.Footnote 46 Just as bookish artists and enthusiasts delight in leather bindings, the aesthetics of illustrated dust jackets, and the codex as an art medium, printers who foreground the materiality of their practice are deliberately emphasizing the particular sensorial qualities of print.

One complicating issue with the contemporary trend for bite impressions is that to press lead into paper, especially if the paper has not be dampened first, requires the printer to use so much packing as to make a deep bite is also to damage the type. Little by little, the metal type is worn away by this approach, and older wood type can crack under too much pressure. When so much of the type that printers today use is antique and, in some cases irreplaceable, there is concern, especially in the conservation community, that aggressive biting is inappropriately degrading pieces of type as artefacts. Hugill-Fontanel concludes her essay on ‘Impression’ with this advice to printers: ‘[D]on’t settle into the bite for bite’s sake hoopla … Practice safe impression!’Footnote 47 Yet, since the bite is what distinguishes relief from digital printing, it’s unlikely that the aesthetic preference for deep impressions will go away any time soon; in fact, many printers have found ways around this by creating new photopolymer plates that don’t need quite such a careful approach as antique blocks and sorts do. The bite offers a tactile experience that contains vestiges of strength and power. One way of distinguishing letterpress or relief printing from laser or digital is to run a finger along the text. The texture resulting from a bite impression matters and has meaning to letterpress printers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, who practice this craft even as it is no longer a commercially dominant printing technology. The kiss is still prized by many practitioners and in library and museum settings, but the biters are also here to stay.

It might be worth pausing here for a moment, speaking of the bite and the kiss, to consider what exactly an impression is and what it means to make one. In various contexts, the term takes on new meanings: in elocution or poetic metre, an impression refers to a stress or emphasis; materially, it’s a mark produced on any surface by pressure; and even in the specialized discourse of printing and bibliography, there are numerous meanings of the term, since it refers to the mark made by the type in the paper but also to a printing of a number of copies that form one issue or course of printing. Impressions in the social or interpersonal sense are nearly always gendered in myriad conscious and unconscious ways. Like Cathleen A. Baker and Rebecca M. Chung, the editors of Making Impressions: Women in Printing and Publishing (2020), I find the layered meaning useful when thinking about women in print: they ‘make impressions’ in all of these different senses of the word. As sometimes-conspicuous historical outsiders, women stood out in print shops as they pressed their words into paper. Much more broadly, the OED offers a general definition of the noun ‘impression’ as ‘the action involved in the pressure of one thing upon or into the surface of another; also, the effect of this’,Footnote 48 and an 1875 English translation of Plato’s Dialogues follows this same sense: ‘[T]he creation of the world is the impression of order on a previously existing chaos.’Footnote 49 As I discuss particularly in relation to the work of Anaïs Nin in Part 3, this sense of seeking solace also applies in a print context: there is something consoling about the ‘impression of order’, even if that order is available only as a neatly distributed and organized typecase.

1.5 Letterpress in the Late Age of Print

While an entirely linear or progressive narrative history of letterpress would involve some oversimplification, it is important to acknowledge the basic technological shift that attends this moment in print history. In their account of the material and technological development of print technologies in the twentieth century, Sarah Bromage and Helen William note that ‘until the middle of the twentieth century print production remained a labour intensive process. The traditional work practices that had existed since the mid-1800s remained largely unchanged and the workforce was strictly demarcated along work role and gender lines.’Footnote 50 What happens to those reified work roles and gender lines when this old technology finds itself decontextualized in a contemporary context? Even as letterpress ceased to be the technology of choice for newspapers, novels, and many other kinds of everyday texts, towards the end of the twentieth century, it gained a new market for upscale commercial ephemeral products, including wedding invitations and business cards.Footnote 51 It continued, at the same time, to be a form that suited and was intimately tied to experimental literature, activism, and poetry. The 100 years leading up to our present moment – an era Ted Striphas terms ‘the late age of print’, – are marked by a ‘persistent unevenness’ and ‘dynamism’Footnote 52 in the use of print technologies and in the purposes to which those technologies are put. In the case of letterpress printing, Striphas’ characteristic late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century ‘dynamism’ is embodied in the shift away from commercial and newspaper printing at the start of the century and towards art-making, poetry broadside printing, protest posters, postcards, and wedding invitations at the century’s end.

While the vital work of feminist print historians working on earlier periods informs this project, in this study, I am most interested in print production in the twentieth century into the twenty-first, and particularly the relationship between letterpress technologies and experimental literary works created by self-taught modernist women writers. The choice of letterpress when other technologies are available is important but often overlooked in the context of the longer history of the book. Much of the scholarly work on book history and on practices of printing – everything from Robert Darnton’s ‘What is the History of Books?’ (1982, and revisited in 2008) to Roger Chartier’s ‘The Author’s Hand to the Printer’s Mind’ (2013) – specifically focusses on historical periods in which letterpress printing is the dominant commercial mode of transmission for texts. The essential bibliographical and scholarly work of Cait Coker, Margaret J. M. Ezell, Wendy Wall, Helen Smith, Michelle Levy, Kate Ozment, and Sarah Werner, and others on women in print, focusses primarily on a time period when letterpress printing was the default technology for textual circulation. By the mid-twentieth century, however, letterpress printing was no longer something that needed to be done in order for a text or a piece of print to reach its audience. As letterpress printing became more of an aesthetic choice and an artistic practice through the twentieth century, it reverberated with meanings that carried valences inherited from the complicatedly gendered traditions described in earlier periods, often in unpredictable and subtle ways. As the viability of letterpress within the printing industry dwindled with the rise of newer, more efficient equipment, letterpress printing became aligned with museum culture, with heritage, with art, and with community-based and activist initiatives. The histories of feminist do-it-yourself (DIY) initiatives from the beginning of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first are fragmented and often moving. These are stories of resilience and power, and of aesthetic and political radicalism.

1.6 Letterpress as Contemporary Craft

Because letterpress printing and especially hand-setting type became an increasingly niche activity in the twentieth century, it now calls up the full complexity and slipperiness of ‘craft’ as a concept. Drawing on and extending David Pye’s classic formulations of craft theory in The Nature of Art and Workmanship (1968), Alexandra Peat argues that in the early twentieth century: ‘[C]raft could be the authentically human handmade alternative to industrial modernity or something automotive and mechanical; it could be a skilled profession or work done by an amateur with a sense of vocation; it could be the opposite to art or elevated to an art form; it could designate the solidly material or it could carry a spiritual resonance.’Footnote 53 Fundamental to Pye’s theory of craft is the distinction between what he calls the ‘workmanship of risk’ and the ‘workmanship of certainty’. In the former, the outcome or product of a craft practice is not predetermined but depends on the execution of a process by a fallible human being, whereas the latter implies the precision and replicability of modern industrial practice. Pye suggests that printing occupies a complex position between these two poles, requiring skill and care but also resulting in duplication of a similar result over and over once the type is ready to print (one element of risk he leaves out, I think, which I will return to in Part 3 in my discussion of Virginia Woolf’s printing practice, is the contingency of inking). Pye’s association of print with certainty is also an indication of the complex status of print and its relation to the notion of making by hand. Walter Benjamin famously aligns print with reproducibility and replication that lacks ‘the here and now of the original’.Footnote 54 And yet printing using hand presses with movable type now seems difficult to dissociate from traditions of craft and the handmade when the alternative of digital printing is even further removed from the originating hand and far more ‘certain’ in the prints’ easy sameness. Pye argues in his work that in an era when industrial production suffused with certainty is available, craft that involves risk and a great deal of skill and time must be undertaken ‘for love and not for money’.Footnote 55 His theory prefigures also a shift in critical discursive practices in the later part of the twentieth century towards thinking about craft practice as closely aligned with particular forms of contemporary art.

Glenn Adamson points to the specific and complex character of craft practice in the modern and contemporary eras and suggests that ‘modern craft would be best seen not as a paradox or an anachronism, or a set of symptoms, but as a means of articulation. It is not a way of thinking outside of modernity, but a modern way of thinking otherwise.’Footnote 56 The contradictory and slippery nature of craft and its implications are essential in considering the specific nature of letterpress as a creative and material practice. Betty Bright describes contemporary letterpress practice as one experiencing a historic shift in materials, making it ‘a medium ripe for artistic restatement’.Footnote 57 That restatement, however, has occurred variously and with a great deal of complexity. Bright describes the contemporary landscape as one in ‘a state of healthy confusion, as we seek a paradigm that links craft with art and yet is flexible enough to absorb new practices without shutting out the accumulated knowledge that is their backstory’.Footnote 58 This paradigm involves an incredibly delicate balancing act: managing to encourage the lineages and histories of craft practices while at the same time opening up to innovation in what can be an incredibly particular and precise practice with very specific standards and rules. As Peat notes, the reputation of craft often splits dichotomously in a divided critical landscape, but letterpress printing seems to hold all of these contradictions within it: printing by hand is often an ‘and’ rather than an ‘or’ – art and its opposite, amateur and professional, spiritual and solidly material. Craft – like form, as I discussed earlier – is a concept that not only crosses but disassembles the boundaries between material and linguistic: now a contentiously debated term in creative writing pedagogy, the craft of language and the craft of print overlay in uncertain and often ambivalent relation.Footnote 59

Another ‘and’ that applies to certain kinds of modern handicraft is that it’s often part of both the past and present. Through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, therefore, letterpress printing undergoes a transformation from a dominant professional technology essential to the circulation of texts to a niche historically informed pursuit. For modernist and mid-century writers, the use of this technology complicates the very modernity of the works being produced by hand and introduces the rich and manifold questions of craft and aesthetics that come with the choice of hand-printing over mechanical or digital process that are more efficient on a commercial scale.

1.7 Why Letterpress?

A question that must be applied to any examination letterpress of our current era is why do this difficult, finicky, time-consuming thing now, in the twent-first century, when other options for making words appear on paper or even on screens are readily available? The contemporary jeweler and writer Bruce Metcalf asks a similar question of handcraft more generally: ‘Why bother when cutting-edge technology is moving towards the complete automation of manufacturing? … Isn’t it stupidly nostalgic and obsolete, or nearly so?’Footnote 60 Metcalf points to psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of ‘flow’ – a state of deep concentration in which a practitioner feels transported to a realm of intense enjoyment that rewards the hard and patient work, and that often goes into highly skilled activities – as a motivator for craft practitioners. As the printers Cathie Ruggie Saunders and Martha Chiplis point out, there is a strong affective pull for those interested in letterpress now: ‘[T]here is little pleasure greater than the satisfaction gleaned from the humble punch of metal into paper.’Footnote 61 The printing historian Will Ransom similarly suggested in 1929 that maybe the best reason to print is for the pleasure of printing: ‘The simplest and perhaps truest type of private press is that maintained by one who is, at least by desire, a craftsman and finds particular joy in handling type, ink, and paper, with sufficient means and leisure to warrant such an avocation. His literary selection may leave something to be desired and art may be disregarded or amazingly interpreted, but he has a good time.’Footnote 62 Ransom’s observation here – with its male pronouns, characteristic for the time – is also indicative of a longstanding rift between book art as material art and as literary content. Print quality and verse quality were not always aligned, and this notion that book arts and literary arts can operate independently of one another is one reason it remains challenging to marry the two. Learning how to print and learning how to write require very different modes and kinds of education in two historically separate disciplines. It’s important to note also in Ransom’s suggestion the privileged nature of this craft, especially when it’s undertaken as an amateur pursuit rather than as a profession: in 1929 as now, it requires ‘sufficient means and leisure’ to produce letterpress prints, particularly if the press is not a specifically or dominantly commercial enterprise.

The possible justifications for producing letterpress works also change through the course of the twentieth century. At first, small hand presses and other such printing equipment was being sold off from the trades and was relatively readily available; buying a tabletop Kelsey or Adana press in 1930 might be something like buying a photocopier/scanner today (Anaïs Nin, about whom I write more later, bought her treadle-operated platen press for $75 USD in 1941, which is the equivalent of about $1,250 USD in 2021 currency. Similarly, the woodcut artist J. J. Lankes purchased a Washington-Hoe press for $50,Footnote 63 ‘shortly after the war when [he] was given to understand that many were broken up and disposed of as scrap iron – no doubt for making shells, a more profitable business than making prints)’.Footnote 64 In 1929, the Excelsior Printing Supply Company was advertising its small tabletop Kelsey 3’x5’ presses along with a starter kit of supplies and an instructional manual for $15.70 USD.Footnote 65

For printers working for much of the century, the choice of letterpress as a technology was less about historical nostalgia and more about agency and availability: the larger commercial presses were dauntingly large and heavy, and digital printing obviously wasn’t available until relatively recently. To make beautiful prints within a domestic setting, a tabletop hand press like a Kelsey (in the United States) or an Adana (in the UK) was a logical choice. In the twenty-first century, however, and as a resurgence in demand for these smaller presses also started to arise, the availability of the machines decreased and the cost correspondingly increased. Now, various do-it-yourself and even build-it-yourself printing presses have been devised both for sale and for wider distribution. The Provisional Press Project, for example, arose during the 2020 pandemic as a means of distributing functional flat-bed platen presses for artists and students who lacked access to their studios during public health closures.Footnote 66 The prevalence of these kinds of new technology for an old craft brings us back to the relief impression as a primary motivation for letterpress printing: without the cast-iron originals creating the prints, the bite impression itself is the remaining element that links a letterpress work back to print history.

It is important to note that obsolescence isn’t quite the right way of describing letterpress, even today, because the old machinery – assuming it’s been cared for or restored –actually still works, and in many ways the hybrid practices of digital technology and letterpress become more and more effective at printing as the century goes on. This is not the experience of trying to run Windows 95 on a 2020 PC, in which case the operating system is obsolete in the sense that it no longer functions in concert with a new machine. This is rather more like the contemporary trend, indicated by the popularity of social media and crafting sites like Ravelry and Etsy, for knitting. The knitting needles still work as knitting needles have done since eleventh-century Egypt – it is just that there is no need to use them these days in order to procure a garment to help you stay warm. The time and embodied consciousness that made a piece of letterpress printing is there, even if, or maybe especially because, you can’t always see it and even if, or perhaps especially because, you could get the words on the page more expediently in some other way.

2 Learning

This part explores the question of how letterpress printing, as a skilled craft, has been taught and learned through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Throughout this section, I show how printers’ educations and labour conditions have been gendered. A crucial thread here is the contrast between education in formal trades and union participation and education that occurs outside those structures through books, online resources, and manuals, or through small print networks or countercultural groups. This distinction in modes of education and degrees of labour organization also raises the matter of distinguishing between fine printers, in the tradition of, for instance, William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, and focussing on newspapers, advertisements, handbills, and other trade content.

I hope that in addition to outlining the history of how different kinds of printers learned to print, this section might also be fruitfully used as a resource for teaching, especially in combination with some of the supplementary materials in the bibliography. I therefore begin here with my own brief illustration of the basic process of setting type and printing by hand. I then move through the historical structures and debates around printing education and labour organization through the century. This part lays the foundation for understanding and interpreting the written accounts, images, and prints in the sections that follow: in order to appreciate the significance of printing language, it’s important to understand the mechanics of the process and how these mechanics reflected the complex characterization of printing as a form of craft, a form of art, and a form of labour.

2.1 Fundamentals of the Letterpress Printing Process

When people are learning to set type, what exactly is it that they need to know? The metaphors and figural connections that writers and printers ascribe to the language of their medium is governed by a very specific set of material acts, objects, and principles. To begin from the (mechanical) beginning: letterpress is a form of relief printing in which an inked, raised surface is impressed on a piece of paper or other substrate. Before 1900, it wouldn’t have been particularly necessary to put the ‘letterpress’ in front of ‘printing’, because textual printing would almost always have been done this way.Footnote 67 The machine used to create this type of print varied over time and still varies, and the degree of handwork required can be more or less depending on the intervening technologies that aid the process.

For the most basic letterpress setup, composing (sometimes otherwise called setting type, hand setting, or typesetting) takes place letter by letter, with individual sorts lined up in a composing stick.

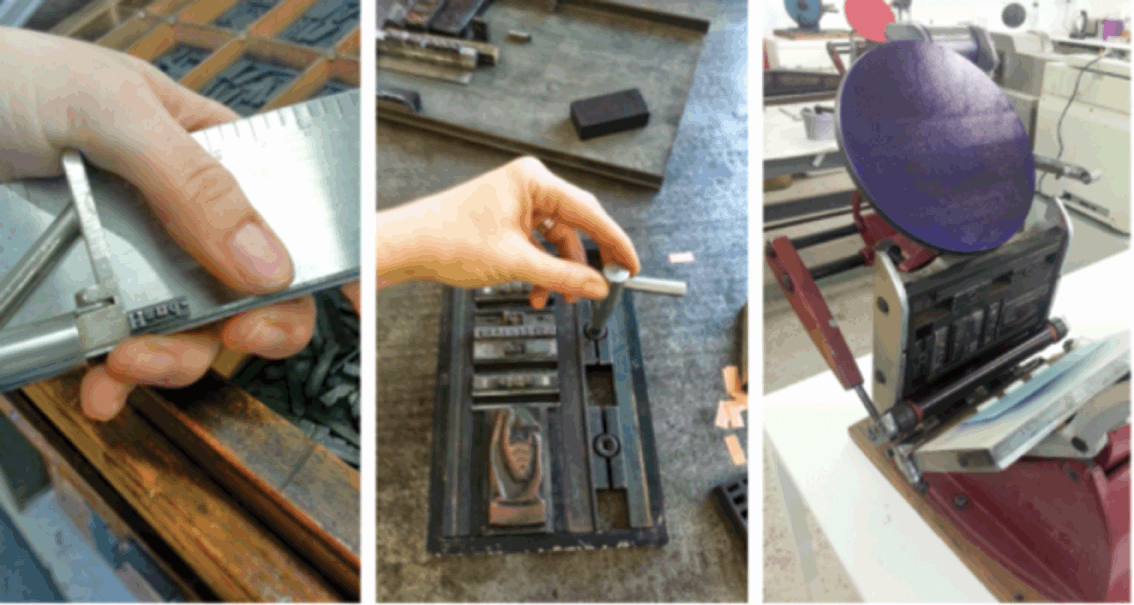

Figure 2 The process of setting type and printing on an Adana tabletop press.

Each line is then placed on a large, flat imposing stone and surrounded with wooden furniture, locked up using metal quoins into a frame called a chase, and then the whole thing – now called a forme – is laid on the press bed. The whole process of preparing for printing is called makeready. Then, ink is applied either directly to the type on the form using a hand roller or using an automatic inking function on the machine. The substrate is fed into the machine – and there are many variations on possible types of machine, ranging from the portable tabletop press to behemoth poster presses, which I will discuss further later – and then, voilà!, you can pull your print. In many larger commercial operations, the compositor who set the type and the pressman who pulled the prints were separate roles carried out by individuals with distinct skills and training, although learning the whole trade was often part of an apprenticeship process, and in many small operations a printer would carry out all the roles.

Linotype and intertype machines, invented in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and used widely until the 1970s and 1980s, mechanized the typesetting process. The operator used a keyboard to assemble matrices, not sorts, which then cast a whole line at a time (a ‘line o’ type’ also called a slug) and eliminated one step in the process of typesetting. In the UK, monotype, a different process using perforated paper tape, was the preferred technological advancement in typesetting. These machines eliminated the need to hold a stick of type and the labour of dissing it for reuse after printing. Once the work was printed, used slugs could be melted down to be reused, and the process began over again. Commonly used early in the century in newspaper operations, linotype casters were huge and expensive, so they tended not to be common in domestic or small operations. However, there are still a few of them kicking around in operation at small presses today.Footnote 68 Later in the twentieth century, it became hard even to give them away, and many were scrapped after they fell out of general use for newspapers in the 1980s. The preservation, restoration, and resale of letterpress equipment has become a highly specialized, niche activity. It is now possible to acquire some equipment through eBay and other online marketplaces, as DeGaine reminds us, but for much of the later twentieth century and early twenty-first, specialist dealers, like Don Black Linecasting in Toronto (now sadly closed) tended to be the most reliable providers to furnish new printers with equipment that had been lovingly restored to usable condition.

2.2 Hierarchies of Labour: Apprenticeships, Unions, and the Printing Trade

Before considering the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, it’s necessary to briefly address the long history of gendered labour in the printing industry and delineate the ways in which the systems and structures of labour in these worlds continued throughout the century to bear on perceptions of women as printers. Well into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the printing industry continued to be impacted by what it inherited: exclusionary trade unions, factory acts that legislated restrictions on female participation in industrial labour, and cultures of misogyny and gender essentialism.

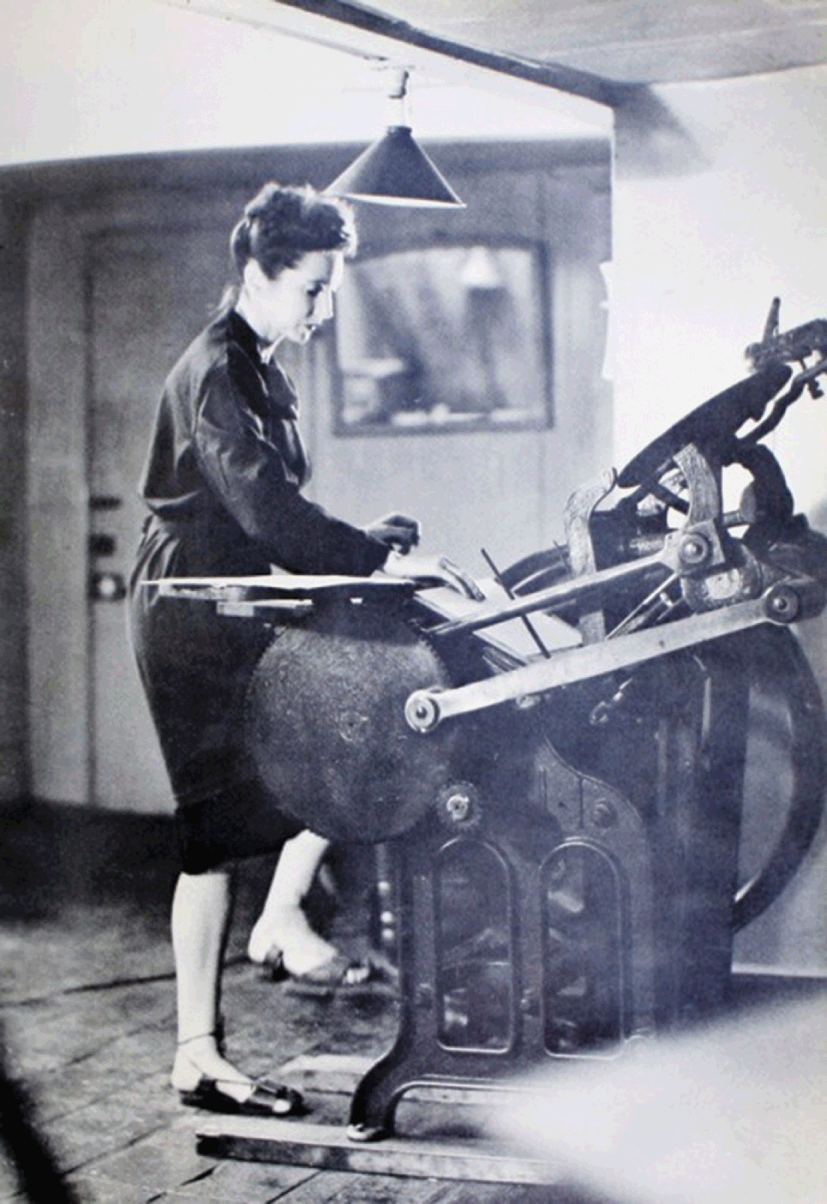

From the fifteenth century onwards, letterpress printing was a trade most commonly learned ‘on the job’ through a hierarchical apprenticeship programme. Printers’ ‘devils’, as they were commonly called, were charged with the dirtiest and most repetitive jobs in the shop: cleaning the floors and dealing with the ‘hellbox’ of discarded type destined to go back to the type foundry. Eventually they worked their way up to more skilled roles, but only after having spent years observing the craft and learning from within the printing space. By the nineteenth century, a fairly rigid apprenticeship system of hiring young boys for these jobs was standard across most of Europe. The completion of an apprenticeship led to the status of journeyman printer, and as Cynthia Cockburn notes: ‘[T]he butterfly that emerged from the chrysalis of apprenticeship could never again be confused with the mere grubs of the labouring world’;Footnote 69 this repeated trope of ‘youthful suffering to win manly status’ was a significant narrative element of the structure of print education right up to the twentieth century.

It’s important to emphasize that the culture of exclusionary and misogynist practice in the print shop did not mean that there were no women printers. It did mean, however, that if women were working in these contexts, no matter the job they were doing, they very rarely had access to the same rigorous training programme as men who performed the same operations. As the historian Ulla Wikander notes, in the nineteenth century: ‘[G]irls were not accepted into apprenticeship programs. Refusing women access to education was a method of exclusion.’Footnote 70 While men could be assured of their professional status in a skilled trade following their apprenticeships, there was, as Sian Reynolds puts it, ‘no such thing as a “time-served journeywoman” in printing’,Footnote 71 even though women did in fact work in the industry. As Mary Biggs points out, two basic views of the gender dynamics of the print industry of this early part of the century tend to dominate: ‘[T]he union view of the typographers as pioneer egalitarians, and the feminist view of the union as a destroyer of the first and best opportunity women had to participate in a remunerative skilled trade. As far as they go, both views are correct.’Footnote 72 As in many labour markets, significant political and social complexity arose around the matters of equal pay, training, and unionization, especially since printing was considered a prestigious industrial craft associated with the dissemination of literature and of knowledge. Moreover, as Christina Burr notes: ‘[A] gender division of labour was in place with women occupying those positions socially defined as unskilled, namely press feeding, and folding, collating, and stitching in the bindery.’Footnote 73 These activities notably tended to exclude what is sometimes referred to in contemporary documents as the ‘heavy’ work of actually pulling the prints: of making impressions. As Karen Holmberg points out, the legacy of assigning women less ‘skilled’ roles fed back into some of the erasures of labour in the historical record that now pose challenges for historical research: ‘[E]ven in the latter part of the twentieth century, printing still bore the mark of the masculine-guild mentality; the male was the owner and master printer, while those who labored at setting type, folding, sewing, or binding, were never acknowledged in the published book.’Footnote 74

The recovery of particular settings or stories where women participated in the print industry makes up the bulk of existing secondary criticism about women in print. As Moog notes, one of the earliest and most frequently cited examples of European women printing were the nuns working at the Convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli in Florence in 1476, their labour documented in the convent’s records.Footnote 75 Women were not always entirely excluded from the labour unions later, either. The International Typographical Union (ITU), founded in the United States of America in 1852, admitted some women as early as 1869. Women’s branches and subgroups and advisory committees arose in various contexts in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including local branches, such as the Women’s Co-Operative Printing Union of San Francisco (1869) and the Women’s International Auxiliary (1909). Biggs also points to the existence of women-run and operated full production organizations in the nineteenth century, such as the Bohemian Women’s Publishing Company of Chicago and the Victoria Press.Footnote 76 However, there remained significant complexity and variety in women’s participation both in the unions (which also fragmented along different professional lines over the years) and in the industry as a whole, in different national contexts. In France, for example, there was a massive growth in female employment in the printing trades between 1866 and 1896, largely because women were working for less pay and were therefore attractive to employers.Footnote 77 The situation was not the same in the UK. There, male union leaders were more successful in excluding women from the trade, and as Reynolds points out, there were further regional differences between the north and the south of the UK and in Scotland. Moreover, the Factory Act of 1867 legislated restrictions on the labour of women in industrial sectors in England: they could work no more than ten hours a day. No such restrictions were placed on men’s working hours. As Reynolds notes, in the twentieth century, ‘the printing trade was in many countries a particular focus both for new technology and the employment of women’Footnote 78 and as such contemporary assessments of the printing trade were sites of debate about female labour in general.

Exclusionary tactics were linguistic as well as practice based. As Alice Staveley remarks, even as women were admitted into unions and were undertaking printing work, ‘the rhetoric of exclusion remained powerful and carried a frisson of ecclesiastical prohibition’Footnote 79 since the union branches, called ‘chapels’, were often possessed of extravagantly masculine cultures. A glaring example of such rhetoric in the printing trades appears in a 1904 study supported by the Women’s Industrial Council in the UK called Women in the Printing Trades: A Sociological Study. In this work, author J. Ramsay McDonald (who was subsequently British Prime Minister from 1929 to 1931) lays out the conditions and structures around women’s labour and particularly focusses on the matter of equal pay for equal work. In an introductory section, ‘The Trades Described’, McDonald notes that each step in the letterpress printing process requires ‘a high degree of skill and experience … which women seldom attain’.Footnote 80 Women in the Printing Trades maintains throughout that it is impossible to see women’s work in printing as equal to men’s. McDonald suggests that women fail to sufficiently advocate for their own proper conditions of labour and show little ambition for innovation or change: ‘[S]he has preferred to remain incompetent.’Footnote 81 The ‘industrial mind and capacity of women’Footnote 82 is shown here not to be held in very high regard. Predictable discriminatory ideas about marriage and motherhood as barriers to proper work (‘liabilit[ies]’Footnote 83 in McDonald’s terms), along with a supposed lack of physical strength, fed into an overall dismissal of the notion that women might be considered on any kind of equal ground. Not to mention McDonald’s basic understanding of gender itself as fixed, tied to physiology and biological determinism, and devoid of personal or cultural expressions or of a spectrum of possible identities. McDonald’s ideas about women printers seem to be shared by the shop and press owners he studies and interviews. One London firm interviewed in the study described the idea of paying women at the same rate as men as ‘ridiculous … They would never be worth as much because they stay so little time.’Footnote 84

Ramsay’s study did, however, encourage some feminist discursive interventions into debates about industrialism and labour. Reviewing McDonald’s study in the Journal of Political Economy in 1905, Edith Abbott writes: ‘[O]ne is forced to the conclusion that [the causes of inequality outlined by McDonald] are likely to disappear wholly when we have that longed-for “readjustment of traditional modes of thought” to the employment of women; and, with this change in the attitude of the community toward her work, the woman wage-earner will be found to be as energetic, ambitious, and competent as the man.’Footnote 85 This first-wave feminist perspective clearly indicates the relationship between discussion of industrial work in the printing industry and perceptions of female labour and gender roles more broadly. Abbott also suggests here that all perceived barriers to women’s participation were just that: perceived rather than actual, products of culture rather than empirical facts.

Much later than McDonald’s study, there continued to be a male-dominated culture in the industrial world of letterpress printing and particularly in the unions. The union activist and printer Gail Cartmail notes that, in the 1970s and 1980s, the National Graphical Association (NGA) in the UK was jokingly referred to as ‘No Girls Allowed’.Footnote 86 Reynolds notes that following her own education in hand setting at art college, she learned of the ban on women from joining the NGA, the injustice of which was partly what drove her to write historically about the female compositors who worked on the Encyclopedia Britannica.Footnote 87 The exclusionary union organization was not a deterrent for Cartmail, who pursued equal pay for women and advocated for a broader diversity in the industry: ‘[W]hat I know’, she writes, ‘is that diversity strengthens organizations, and that includes workers’ organizations … women made it possible for the union to encourage a much wider diversity including ethnicity and understanding aspects of disability.’Footnote 88 With Cartmail’s remarks, it is possible to trace the emergence of some understanding of intersectional constructions of identity in the world of printing, with its long-standing history of privileging white, male, cis individuals as labouring bodies.

The labour landscape in the commercial world of print altered significantly as new technologies supplanted letterpress as the dominant commercial mode. As letterpress declined in the mid-twentieth century, an alternative method of printing was starting to take over in the commercial trades: offset lithography. The key aesthetic difference between lithography and letterpress is that the former is a flat method rather than a relief method. Lithography also differs functionally from letterpress in the sense that the same printing surface can incorporate both text and images, making their integration on the page much more straightforward. Offset lithography (sometimes called photolithography) really took off in the 1960s. Xerography, the precursor of digital printing, was around by 1949. Technologies coexisted for quite some time, until eventually relief printing became a rarity in the commercial sphere around the mid-to-late 1980s.

By 1986, the ITU had disbanded, owing to the technological shifts that had drastically changed and fragmented the industry. This event in the history of letterpress printing was structurally significant. With the closure of commercial letterpress operations and the move to speedier technologies, the rigid labour structures that had dominated the commercial industry gave way to a more fragmented and less regulated world for letterpress printers. This is the moment – if there can be a single moment – when letterpress structurally moved from industrial practice to craft, and from a highly regulated industry to a world of freelancers, artists, and self-employed practitioners. Cockburn documents this moment of transition in the UK context in her beautiful study Brothers, in which she articulates the decline of the compositors’ professional role in the 1980s as a transition with an enormous impact on professional cultures of masculinity.

While the dissolution of many of the systems and structures that long governed the industrial print industry made way for more diverse participation, it has also led to a problem now common across industries of late-capitalist neoliberal work structures. Many letterpress printers and graphic designers now work as freelancers or run their own businesses. This of course means they often work without the benefits, standards, and protections afforded to unionized workers. As Fanni, Flodmark, and Kaaman note, the contemporary labour situation is a ‘precarious, tough, and in many ways lonely condition. But at the same time framed with apparently positive words like freedom and flexibility’. While the unions had their glaring problems, they also did the important work that unions do of advocating for reasonable conditions, survivable hours, and safe labour practices. They also created communities around the industry, and while they were not communities with open doors or feminist ethics, they offered the possibility of collegiality and shared work. As Fanni, Flodmark, and Kaamen note, their own interest in the history of their professions was sparked by a desire to seek in the past a sense of ‘collectivity, community, and an understanding of material conditions’Footnote 89 that seems absent in twenty-first-century fragmented and individualistic work conditions.

2.3 Other Ways to Learn: Handbooks and Guides

Since the structures outlined earlier were hardly inclusive, although efforts on the part of women like Cartmail made significant changes, women often learned to print from books and manuals or informally from friends with experience rather than from formal education in schools or from the predictable and rigid systems of trade apprenticeship programmes. The exclusionary structures of printing described also apply most to the commercial trades producing newspapers, large-run bestsellers, and other commercial artefacts.

Smaller operations often took different approaches to education. The poet Laura Riding, for example, learned how to set type from a friend, Vyvyan Richards, who herself had acquired a press to produce fine editions of T. E. Lawrence’s work.Footnote 90 Virginia Woolf took a similar approach, learning from ‘the old printer’, Mr McDermott, a neighbour in Richmond, after being denied entry to the London School of Printing because of her class background and her established reputation as a literary journalist. Anaïs Nin learned to print from manuals she borrowed from the library. Yet letterpress printing (especially the part of the process known as makeready) is the kind of thing that is much, much easier to learn by being shown physically how to do it. The apprenticeship model in the printing trades was in place for good pedagogical reasons.Footnote 91 Even early printing manuals were mostly designed more as notes and reminders for those who had already apprenticed. Learning to print from a printing manual is about as easy as learning to ride a bicycle by reading a book about spokes and tires: it is possible, and the guides are definitely useful, but there are better ways.

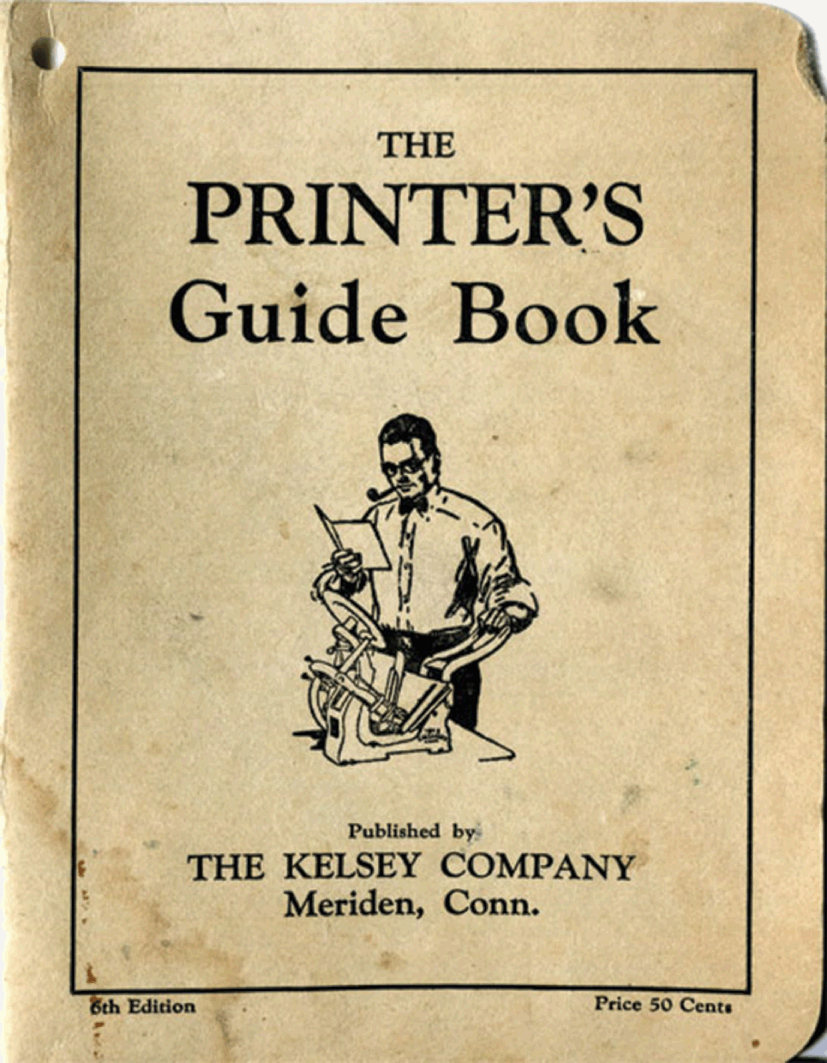

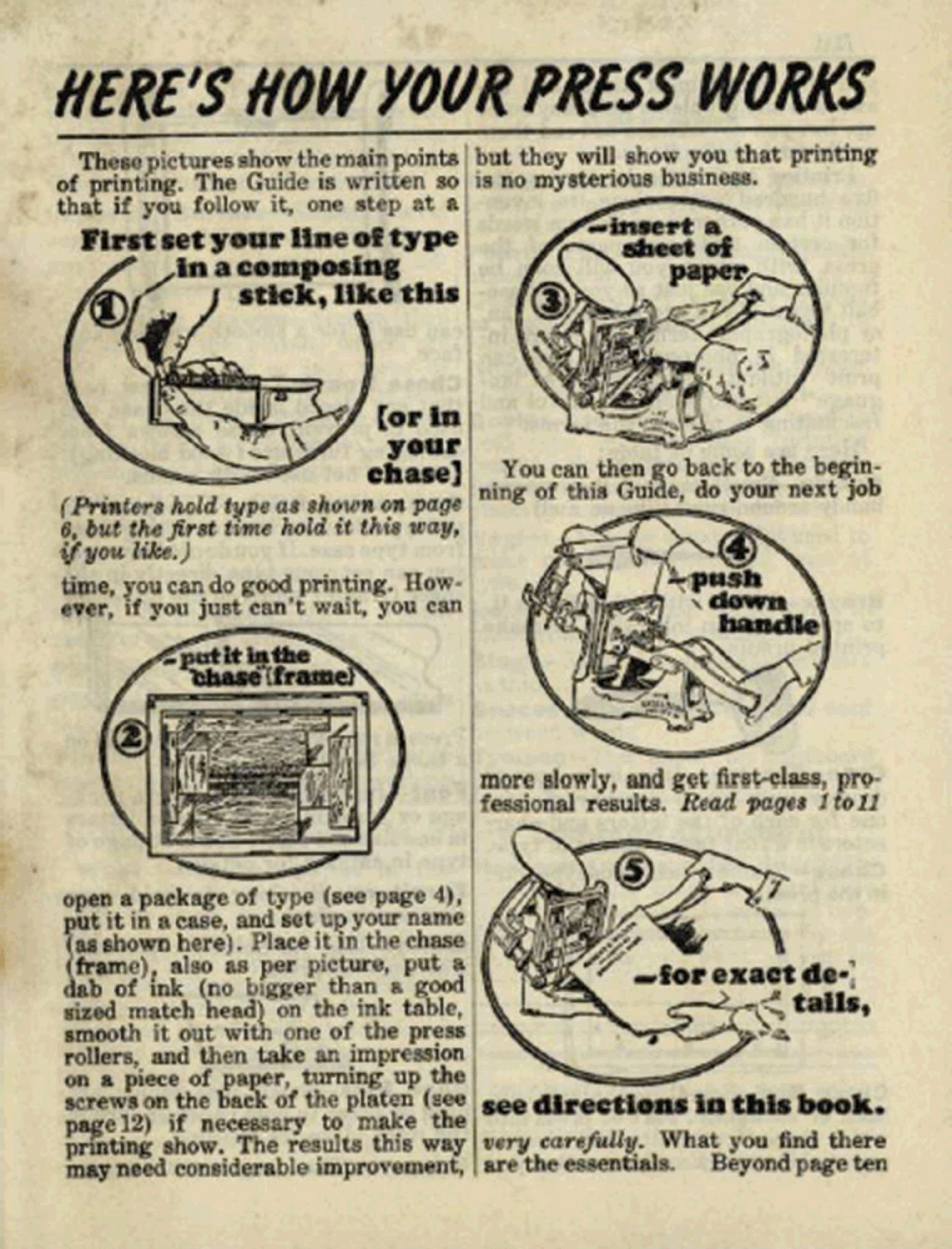

That said, various manuals and guides to printing were produced from the very earliest days of print, and adapted to reflect the different types of machinery that became available through the century. Manuals were not originally designed as stand-alone resources, but rather as resources for printers who had already undertaken apprenticeships to remind them of good habits and best practices. In her study of some of the most well-known early printing manuals, Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (1685) and John Smith’s The Printer’s Grammar (1755), Maruca points out that while these guides have tended to be read as neutral instructional documents, ‘we can begin to glean the local and historical meanings of print [from analyzing manuals] and see it not as a fixed essence, but an active and ever-changing ideological tool.’Footnote 92 Reading Moxon’s language of typography for its gendered implications, Maruca points to Moxon’s ‘intense, almost lascivious’ descriptions of typecasting as evidence for the frequent linguistic slippage between the bodies of the type and the body of the printing labourer.Footnote 93 While the twentieth-century guides are slightly less overtly sexualized than the examples Maruca pulls from Moxon, they nevertheless display a situated gendered identity. A number of pamphlet-sized guides aimed at the hobbyist were included alongside presses when they were purchased, as in this example of The Printer’s Guide Book produced by the Excelsior company to accompany its hobby-grade tabletop Kelsey presses, complete with an illustration of a well-to-do gentleman in a bowtie with his tabletop press, demurely smoking a pipe as he holds up his perfect print (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The Printer’s Guide Book (1929).

From the outset, then, it is clear that even fairly straightforward-seeming technical manuals outlining print processes are far from genderless objects. The manual goes on to show in simple line illustrations and sparse text that ‘printing is no mysterious business’,Footnote 94 although they concede that it does take practice to get good results. To start with, they illustrate the process of setting type and pulling prints, as depicted in Figure 4, starting with the printer’s name.

Figure 4 Process illustration from The Printer’s Guide Book (1929).

In addition to manuals like these that accompanied the presses themselves, the companies also often produced newsletters with tips and tricks for printers, such as Kelsey’s ‘The Printer’s Helper’ and Adana’s ‘Printswift’. When I examined copies of these I found, unsurprisingly, that the male pronoun was used exclusively in the instructions in these publications. I won’t belabour the point, but a characteristic example from a 1963 issue of ‘The Printer’s Helper’ will perhaps suffice to illustrate the tone: ‘Every printer knows the necessity of getting all the lines in a job of equal tightness if he is not to have trouble with the characters either working up when he is printing or even dropping out before he is able to get the chase in the press. Many learn this through experience, in fact most of us.’Footnote 95 The universal ‘every printer’ gives way here to ‘he’ the printer, and concludes with the first-person plural: a rhetorical indication that women are not the target audience. While it would be reasonable to argue that the singular ‘he’ was often used as neutral at this time, the assumed masculinity of the reading audience is even more overt elsewhere in the newsletters. A regular column in the newsletters was the ‘A Kelsey Man Comments On’ section. The readers who wrote to the newsletter and had their letters printed were men, and there was a general development of a community of ‘Kelsey Men’ as a kind of brand-identified group. Unlike the large, expensive commercial cylinder presses, the Kelsey tabletop hand presses were generally aimed at amateur printers or at non-printing businesses seeking to do their own printing ‘in-house’, and even when attempting to sell products to younger users, the target demographic was ‘boys’ rather than youth or children in general.Footnote 96 While the dapper, leisurely masculinity portrayed in these marketing and instructional materials is particular to Kelsey’s brand, it indicates that even when access to hobby materials or machines opens up to amateurs outside of the trade, the discourse doesn’t cease to be exclusionary. Even if a woman or non-binary person could certainly buy their own Kelsey press to do ‘real printing’, the accompanying ephemera is evidently not written for her or for them.

The existence of word-of-mouth culture, small collectives, and pamphlets and books for education hasn’t, of course, entirely supplanted more formal educational processes for learning how to print. Many women now learn, as I did, to print at university; in studios offering classes; in specialized courses such as the Rare Book School;Footnote 97 or in art school. By an informal count there are now at least twenty-six post-secondary printmaking programmes at universities and fine arts schools in the United States of America, the UK, and Canada with dedicated letterpress components.Footnote 98 These tend to be part of BFA programmes or graduate arts and humanities programmes, although the variety of courses and offerings crosses disciplines and schools. Even more weekend or week-long workshops and informal courses through community letterpress studios, museums, and special collections are rising worldwide, and printing museums around the world offer demonstrations, open days, and events.Footnote 99