Numerous terms have been used to describe patients who present with symptoms that cannot be explained by organic disease: individuals have been diagnosed with hysteria, conversion disorder, somatisation, hypochondriasis, dissociative disorder; symptoms have been described as psychosomatic, non-organic, functional, medically unexplained. This diversity of diagnostic terms has created difficulties in both classification and research that some have sought to address (Reference Wessely and WhiteWessely 2004; Reference KroenkeKroenke 2006, Reference Kroenke, Sharpe and Sykes2007). Many of these words have taken on a pejorative meaning over the years, and for this reason we prefer the simple, descriptive phrase ‘medically unexplained symptoms’.

Numerous psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions have been used to tackle this problem. In particular, approaches based on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) have been gaining ground over the past decade or so, and their validity is being increasingly recognised (Reference Thompson and PageThompson 2007).

We both work in a general hospital, in a clinic to which the hospital's physicians and surgeons refer patients in whom no organic cause can be found for the symptoms. Our aim in this article is to outline the way our clinic operates and to describe the CBT-based approach we take to treat patients suffering from these debilitating disorders.

Historical overview

Modern medical interventions for neurologically unexplained symptoms began towards the end of the 19th century with the work of Freud and Breuer. They initially tried hypnosis, before turning to analytical methods that ultimately led to the development of the numerous schools of psychoanalysis and broadened to encompass the treatment of many forms of psychological disorder.

The First World War was influential in the development of treatments for neurologically unexplained symptoms in Britain, as cases of ‘shell shock’ were first recorded (Reference Macpherson, Herringham and ElliottMacpherson 1923). This brought the concept of neurological symptoms generated by psychological trauma firmly into the public eye. Much of this early work was conducted along psychoanalytic lines, reflecting the culture of the time. The USA's involvement in the Second World War spurred the interest of US neurologists in using psychological approaches to help war veterans presenting with ‘conversion’ and related disorders.

Far from being an isolated phenomenon, medically unexplained symptoms occur in many forms and situations, and in many cultures around the world. Consequently, the search for successful interventions has continued. For example, psychotherapeutic approaches emerging from the coming together of cognitive and behavioural theories in the 1960s have also found applications in the treatment of medically unexplained symptoms. Other psychotherapeutic interventions remain in use, such as that integrating attachment theory and existential psychology (Reference Maunder and HunterMaunder 2004).

Epidemiology

Studies of patients referred to neurologists have consistently shown that in 10–30% of cases no anatomical or physiological causation for symptoms can be found (Reference Carson, Ringbauer and StoneCarson 2000; Reference Allet and AlletAllet 2006). Such symptoms, which range from isolated non-epileptic seizures to debilitating multiple neuropathies, are frequently described as ‘functional’.

Most communities around the world have demonstrated medically unexplained symptoms within their populations (Reference Gureje, Simon and GregoryGureje 1997). Evidence suggests that these symptoms are more common in women than in men (Reference Kroenke and PriceKroenke 1993), a finding supported by preliminary figures from our clinic (details available on request).

One of the main difficulties for these patients is that they tend to do badly in treatment and often fail to progress. Up to 50% have persisting symptoms (Reference Carson, Best and PostmaCarson 2003) that remain for many years (Reference Reid, Crayford and PatelReid 2003).

Difficulties faced by practitioners

This poor prognosis reflects a genuine difficulty on the part of practitioners in trying to understand what allows such behaviours to develop. There is also a tendency among clinicians to judge these people harshly or to be dismissive of their plight; many are referred onto psychiatric services, with little true understanding of what this will achieve (Reference Bass, Peveler and HouseBass 2001; Reference Page and WesselyPage 2003). Doctors often categorise patients with medically unexplained symptoms as malingering or as manufacturing their symptoms, although the DSM–IV classification of somatoform disorders offers an alternative: ‘The symptoms are not intentionally produced or feigned for material gain (Malingering) or to occupy the sick role (Factitious Disorder). This is an important factor and one which can be overlooked by physicians’ (American Psychiatric Association 2000: p. 491).

Theories of causation

Numerous theories have been put forward to explain how medically unexplained symptoms emerge. Some posit structural brain abnormalities (Reference Ghaffar, Staines and FeinsteinGhaffar 2006); others suggest altered mechanisms of attribution (Reference SenskySensky 1997). Further hypotheses have focused on personality and coping styles (Reference BrownBrown 2004), disorders of volition and socio-physiological factors (Reference Kirmayer, Groleau and LooperKirmayer 2004).

However, nobody has yet been able to explain convincingly why some people develop medically unexplained symptoms whereas others do not. Unique factors specific to the patient's circumstances are likely to have an influence, making generalised theories about causation difficult to apply to the individual or to fit neatly into a traditional medical approach (Reference Butler, Evans and GreavesButler 2004).

Treatment: a practical example

A CBT-based treatment

Successful work using CBT-based interventions to treating physical symptoms has been gaining ground. Cognitive–behavioural therapy is an effective treatment for hypochondriasis, a disorder which has some overlap with medically unexplained neurological symptoms (Reference Barsky and AhernBarsky 2004); and it is also a useful treatment for non-specific chest pain (Reference Kisely, Campbell and SkerrittKisely 2005).

In light of such results we adopted a cognitive–behavioural intervention based on the five areas assessment model (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2001; see below) to treat medically unexplained symptoms in our clinic. Given the lack of consensus regarding the causation of medically unexplained symptoms, we take a symptomatic approach, concentrating on the individual's experience of their symptoms and how they are affected by them. We tend to steer away from attributing a cause. Nevertheless, the causal attributions that a patient makes in relation to their symptoms are often highly relevant (Reference SenskySensky 1997) and in some cases they do become a focus for therapy. Our aim in therapy is to provide an empathic and non-judgemental approach to the patient's plight and to help them set their own realistic goals.

Clinic organisation

Our clinic runs within the general hospital and is not a part of the psychiatric unit; this can help practitioners to relate to their patients better by avoiding what many people see as a ‘stigmatising’ psychiatric diagnostic label. In our experience the patients referred to our clinic appear to find our base in the general hospital out-patient department acceptable.

Our experience suggests that a clinic run once a week and offering each patient an initial five to ten sessions, depending on the presenting problem, would be the minimum required to achieve reasonable results in a main general hospital. Each session should last 1 hour and it should be possible to extend the total number of sessions should the therapist feel that this is required. A multidisciplinary team that includes a physiotherapist, occupational therapist, psychotherapist, and medical and nursing staff is the ideal situation, and the range of professionals involved indicates to the patient that their symptoms are being regarded seriously.

Presentation and referral

Common symptoms experienced by our patients vary widely, but typically they include tremor, paralysis of a limb, speech difficulties, headaches and generalised muscular pains particularly following exertion. Seizures or falls, paraesthesia, difficulties swallowing and fatigue are also common. More generally, bowel complaints, anorexia with weight loss, and chest complaints are seen regularly.

Patients are typically referred to the clinic from the hospital department currently involved in the patient's care. Patients will often have undergone examination in more than one field of medicine and will usually have undergone multiple diagnostic tests such as magnetic resonance imaging and biopsy, often on more than one occasion, before their symptoms are described as medically unexplained. This can have a significant financial cost to healthcare providers, owing to the high number of referrals and disproportionate use of secondary care facilities (Reference Reid, Crayford and PatelReid 2003).

Patients often come to the clinic having spent a considerable amount of their own time and sometimes money researching their symptoms on the internet and trying alternative therapies. A key to treatment success is the patient's willingness to begin to look at their current difficulties in a psychiatric context.

Engagement

Engagement is a key issue with patients who have medically unexplained symptoms, and a crucial factor is finding ways of engaging them in a psychological process when they may be seeking a medical explanation and cure. The first stage is to clarify the patient's understanding of why they have been referred and what they hope to achieve from attendance. It is essential that members of the treatment team make it clear they do not think that the patients are ‘mad’ or that their symptoms are ‘all in the mind’, as these are commonly held and understandable fears (Reference White and MooreyWhite 1997). Usually patients will have made many attempts at trying to manage or improve their symptoms, and although some of these behaviours may ultimately be unhelpful it is a useful engagement tool to highlight the helpful things that they are already doing.

All investigations should be completed and results given to the patient by the investigator before any therapy begins. It can be difficult to engage with someone in a psychological way if they still harbour a hope that the next scan will be the one that finally leads to a diagnosis.

That being said, the therapist providing treatment must also be alive to the possibility that physical symptoms may herald an underlying physiological disorder that has not yet been diagnosed. In other words, the possibility of a physical disorder should never be entirely ruled out. Trying to help the patient to take an integrated view of their symptoms, both physical and psychological, is one of the key tasks during the engagement process. Illustrating the interplay of physical symptoms such as pain and psychological processes such as avoidance can be a useful tool.

Any formulation of the patient's difficulties must be a collaborative process between patient and therapist. Collaboration is essential, both to foster trust, by listening to the patient's worries and beliefs, and to stimulate cooperation with therapy during later sessions. This collaboration between patient and therapist makes CBT a particularly suitable form of intervention for people with medically unexplained symptoms.

Key elements of therapy

It is important to be aware of behaviour and events that arise as a result of the CBT process and to use them to best effect. For example, anxiety about correctly completing homework tasks, sometimes stemming from perfectionistic traits, can occur. Such concerns can prove useful as they can help reveal underlying core beliefs and unhelpful thoughts that can become targets for intervention in future sessions. Non-attendance at sessions and failure to undertake agreed homework can be difficult to overcome. However, the reasons for these should be explored with the patient, as they may be surmountable.

Practical and behavioural interventions can be a very useful way of showing the patient that they are making progress. Goals should be decided on collaboratively, and care must be taken to ensure that they are achievable. Each practical exercise should push the patient's boundaries a little further. After each behavioural experiment, time must be set aside in the session to explore how the patient responded to their experience and what they learned from their response. Any difficulties encountered should be discussed and alternative strategies worked out if necessary.

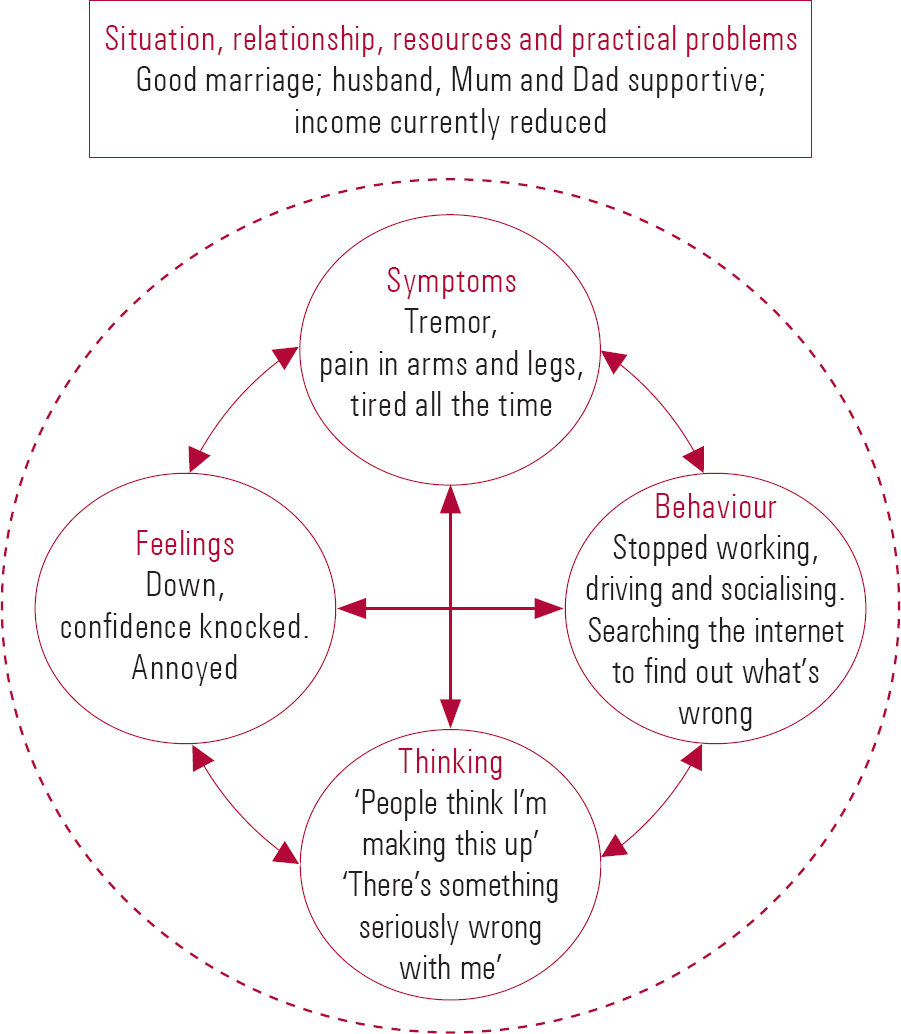

The five areas approach allows patient and therapist to achieve a deeper understanding of the patient's symptoms by bringing into focus and integrating the full range of the patient's experiences in the areas of:

-

• situation, relationships, resources and practical problems

-

• symptoms

-

• behaviours

-

• thinking

-

• feelings.

The patient's own language is used as the key to better understanding. Physical sensations can be hard to describe and patients often use analogies; the therapist should be alert to these and use them when talking with the patient. This allows the patient to feel that all aspects of their experience are important to the therapist, which fosters a good working relationship.

As mentioned above, the psychotherapist should be part of a multidisciplinary team engaged with the patient. It is therefore essential that close cooperation and feedback be maintained with allied professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists, particularly when the patient has motor conversion disorders or multiple neurological problems. The role of the psychotherapist here is often in educating other members of the team about the nature of the patient's symptoms and in preventing the development of anxiety and hostility between the therapeutic team and the patient.

The patient should be aware of this cooperation and be an active partner in it. Feedback from other sources about progress or problems should be discussed with the patient during sessions. Progress should be positively reinforced. Reasons for failure to make progress should be explored and alternative strategies adopted.

Multidisciplinary team meetings with the patient can be a valuable therapeutic tool if used correctly, although it is important, both for the patient and the professionals working with them, that the patient neither feels blame nor is blamed for their symptoms. The therapist should pick this up early and explain the unhelpfulness of blame to the therapeutic process.

(See Key points 1.)

A typical course of therapy

To illustrate how this approach works in practice and to highlight some of the difficulties faced by patients during this process, we present in this section the typical progression of therapy in our clinic.

As in other CBT-based therapies, there should be heavy emphasis on ‘homework’ and agreeing goals with the patient early on. The sessions can be broadly divided into:

-

• assessment sessions, the aim of which is to draw up a psychological formulation

-

• treatment sessions

-

• final or consolidation sessions.

Further follow-up sessions may be offered several months later to check on progress.

The sessions described below are merely a typical run of treatment. Each session should be highly individualised to the patient's own life, symptoms and aspirations. Nevertheless, broad themes frequently emerge and it is these that are described below.

Session 1

During the first session the patient must be allowed time to describe how their symptoms began and how they have affected their life. This information is then reflected back to the patient, often using the five areas assessment model (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2001) (Fig 1).

At the end of the first session the patient may agree that this is a reasonable summary of current difficulties and agree to return for a second session. We often ask patients to complete an activity or thought diary between appointments. The diary might contain an account of what the person is doing each hour of the waking day and also the levels of pleasure and achievement experienced during each activity.

Setting a between-session task at this early stage in treatment helps the patient to become accustomed to the CBT model and demonstrates that work undertaken between sessions is key to the process of therapy.

Session 2

At session 2 patients are often anxious that they have not completed their diaries correctly. It is important to reassure them that this information is for them and therefore it does not have to be ‘perfect’. We usually go through the diary entries with the patient, looking for patterns of behaviour, both positive and negative. It can often become apparent that clear links exist between certain activities or exercise and mood or symptom intensity that patients have not previously noticed or acknowledged. It may also alter the patient's perception that they are ‘doing nothing at all’.

Often, session 2 also provides an opportunity for patients to give additional information on their symptoms which they had forgotten or thought not relevant during the first session. This allows the therapist to further formulate and synthesise the presenting difficulties.

Sessions 3 and 4

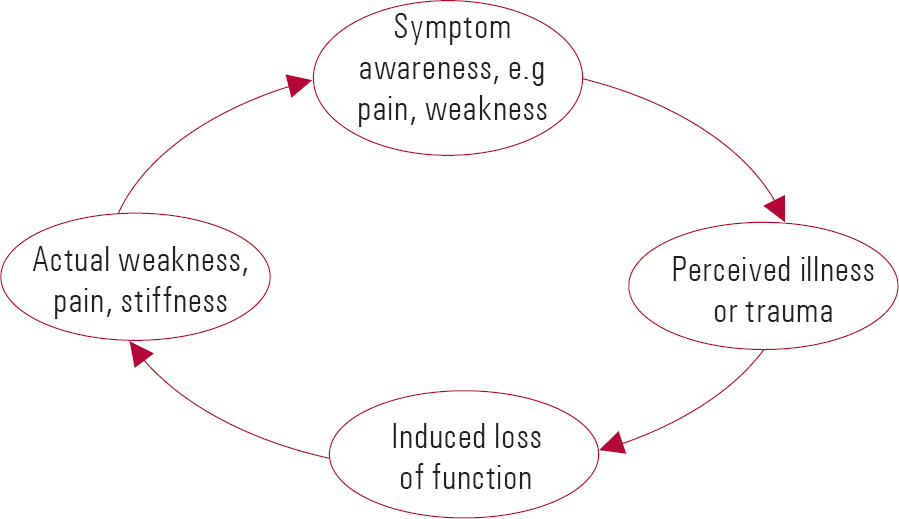

The third and fourth sessions are when treatment goals are set and targets are collaboratively agreed. Pointing out a ‘vicious circle’ of reduced activity or unhelpful behaviour can help the patient to see the impact of their behaviour on both their symptoms and their life (Fig. 2). A plan for overcoming this can then be created. An example might be to help the patient to reduce their symptom-checking behaviours or their use of health-related websites on the internet if it is clear that this forms a pattern of unhelpful behaviour.

Sessions 5 and 6

During sessions 5 and 6 we usually introduce cognitive techniques for managing and challenging unhelpful thoughts. By now, patients can usually keep thought diaries with some degree of success and begin to identify patterns of thinking such as perfectionism and expectations of themselves that are unrealistic in the face of their current symptoms.

Sessions 7 and 8

We continue to consolidate changes that patients have managed to make in their cognitions and activity levels or behaviours. This can often be a good time to work on assertiveness and communication skills, which patients can find helpful when explaining their illness and how it restricts them to health professionals, employers and family.

Sessions 9 and 10

The final two sessions focus on relapse prevention strategies and working through various workplace or social scenarios that the patient has found difficult in the past. If possible, a 6-month follow-up appointment should also be arranged at this stage, to reinforce treatment gains.

An overview of the sessions is given in Box 1.

BOX 1 Outline of therapy

Sessions 1–3

-

• Identification of the patient's key problems and an historical overview of them. Introduction and explanation of the five areas CBT model and how it relates to the patient's problems. Introduction to homework and completion of simple thought/activity diaries. Collaborative setting of treatment goals and targets.

Sessions 4–7

-

• Generation of a flexible psychological formulation of the patient's problems, and checking this in cognitive and behavioural work with the patient. Continuing to work with the patient on achievable goals and allowing them to feed back their own experiences of these tasks.

Sessions 7–10

-

• Continued work on tasks and feedback from the patient. Identification and monitoring of the patient's gains/setbacks in therapy. Consolidation of what has been achieved over the course of therapy.

Conclusions

Over the past century much research has been carried out on the causes of medically unexplained symptoms. Despite this, many people continue to suffer from their debilitating effects. What is more, some clinicians continue to view patients who present with medically unexplained symptoms with a mixture of suspicion, hostility and anxiety. Far more needs to be done in educating fellow practitioners about the nature of these disorders and the practical approaches that can be adopted to tackle them.

As research continues into the multiple causes of these conditions it is important to remain focused on the practical, evidenced-based help that is currently available to patients. In this article we have shown one approach, involving a specialised clinic offering a CBT-based therapy. By operating within the general hospital and making ourselves available to colleagues in medical, surgical and allied professions, we believe that we are educating patients and colleagues and helping to alleviate anxieties surrounding this topic. Although initially slow, our referral rate has increased and we are beginning to see in colleagues working in the general specialties the development of a genuine understanding of medically unexplained conditions that mirrors that of neurologists. This is very good for the numerous patients who live with these conditions and who all too often develop feelings of guilt and despondency in their contacts with medical professionals.

In running a clinic such as ours, close work with the multidisciplinary team is essential. A flexible approach to treatment must be taken, with the involvement of various hospital departments. Patients with more intractable motor conversion disorders, for example, may require longer therapy and treatment by physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Interdisciplinary treatment needs a coordinator, to arrange team meetings, case conferences and so on, and the psychotherapist must be willing to take on this responsibility. With a fully integrated, practical approach progress can be made and hope restored to patients and those who work with them.

MCQs

-

1 Medically unexplained symptoms:

-

a is another name for somatoform disorder

-

b form about 50% of a neurologist's case-load

-

c have a good prognosis

-

d used to be treated by hypnosis

-

e are culturally a Western phenomenon.

-

-

2 An important factor in engagement is:

-

a learning what the patient understands about the reason for referral

-

b that the patient should have ongoing medical investigations

-

c encouraging the patient to take a wholly psychological view of symptoms

-

d finding a cause for symptoms

-

e explaining to the patient that their symptoms are all in the mind and therefore easily resolved.

-

-

3 CBT-based therapy for medically unexplained symptoms:

-

a is widely used

-

b is nearly always successful

-

c has a good evidence base

-

d rarely involves other specialties

-

e should be focused on causation.

-

-

4 The therapist should:

-

a avoid collaboration in the setting of goals and targets

-

b avoid detailed exploration of the patient's beliefs about their symptoms

-

c use the patient's own language

-

d set homework only in the later stages of therapy

-

e encourage the patient to take time off work to recover.

-

-

5 CBT sessions for medically unexplained symptoms:

-

a should be limited to ten sessions

-

b may involve analysis of childhood experiences

-

c should not involve behavioural elements

-

d should avoid psychological formulations

-

e should be symptom focused.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | t | a | f | a | f | a | f |

| b | f | b | f | b | f | b | f | b | f |

| c | f | c | f | c | t | c | t | c | f |

| d | t | d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f |

| e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f | e | t |

KEY POINTS 1 Key elements of psychological therapy for medically unexplained symptoms

|

FIG 1 The five areas assessment model for cognitive–behavioural therapy (courtesy of C. Williams): a typical case summary.

FIG 2 A ‘vicious circle’.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.