Depression frequently co-occurs with schizophrenia, yet in clinical practice it is often missed. This is partly because schizophrenia has at its core a disturbance of affect which is often associated with difficulty in expressing internal emotion. In addition, the restrictive nature of the DSM diagnostic criteria forces researchers into a situation of making a ‘diagnosis’ of a comorbid mood disorder only when all the criteria are fulfilled. For example, a diagnosis of major depressive episode in DSM-IV-TR requires at least 2 weeks of unrelenting low mood or loss of interest, plus a stipulated array of other symptoms (American Psychiatric Association 2000). If a full syndromic definition is applied, the estimated modal rate of major depression in schizophrenia is 25% (Reference SirisSiris 2000). Moreover, there is an overlap of the symptom dimensions of schizophrenia, which include positive, negative, depressive, manic and disorganised, and in turn the merging of affective and non-affective diagnoses without a point of rarity between (Reference UpthegroveUpthegrove 2009). In reality, many patients with schizophrenia express ‘lesser’ forms of depression, not necessarily meeting diagnostic criteria but still carrying significant distress and burden for them. Such individuals have been little studied, making clinicians rely on data from a relatively unrepresentative group of patients who fulfil DSM criteria for a full mood disorder in the context of schizophrenia.

Another nosological difficulty is the problem of how DSM deals (or does not deal) with schizoaffective disorder.Footnote † Originally described by Reference KasaninKasanin (1933), schizoaffective disorder has been a headache for DSM committees for decades. Indeed, it was the only major disorder in DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980) that did not have a set of operationalised diagnostic criteria. When DSM-III-R introduced such criteria in 1987 (American Psychiatric Association 1987), it adopted a very restrictive set. This approach has been continued in subsequent iterations of the DSM, and DSM-IV-TR requires a full affective syndrome (major depressive, manic or mixed episode), frank positive symptoms (criterion A symptoms for schizophrenia) and psychotic symptoms in the absence of mood disorder. The drafts of DSM-5 show consideration being given to another restriction, that mood symptoms are present for at least 30% of the lifetime duration of the illness (Reference Faraone, Blehar and PeppleFaraone 1996). None of this is helpful to clinicians, who more often than not ignore these restrictive rubrics and resort to the schizoaffective label as a useful ‘hold-all’ that carries less stigma than schizophrenia and allows the use of a more symptom-based therapeutic approach (of which more below).

Causality and confounding

Opinions on the link between depression and schizophrenia variously describe depression as intrinsic to the illness, an effect of antipsychotic medication, an expression of negative symptoms of the illness, and a psychological response to and appraisal of psychosis (Reference UpthegroveUpthegrove 2009). Building on this heuristic perspective, Box 1 lists some of the factors that are associated with both schizophrenia and depression. These could equally be considered causal or confounding factors, but for the clinician should provide targets for therapeutic interventions. Indeed, some of these factors can be driven by multiple other influences, reinforcing them and exacerbating the depression. For example, alcohol and other substance misuse is common among people with schizophrenia (Reference Margolese, Malchy and NegreteMargolese 2004), in part at least because of ‘negative affect’ that includes depression (Reference Dixon, Haas and WeidenDixon 1991). A number of these substances lead to worsening depression and thus further substance misuse, setting up and perpetuating a vicious cycle. The substance misuse itself thus becomes an important therapeutic target in dealing with the depression, and vice versa (Reference Lybrand and CaroffLybrand 2009).

BOX 1 Factors associated with both schizophrenia and depression

-

• Social isolation

-

• Loss

-

• Unemployment

-

• Psychosocial stress

-

• Financial difficulties

-

• Adverse life events

-

• Stigma

-

• Alcohol misuse

-

• Illicit substance use

Another important consideration is potential iatrogenic causes of depression in schizophrenia. A number of medications used for the physical health problems that often bedevil people with schizophrenia can themselves carry a risk of depression. More common is that some antipsychotics worsen depression (Reference LewanderLewander 1994). This is perhaps particularly true of the older ‘typical’ antipsychotics, albeit that studies that have looked specifically at the question of whether agents such as haloperidol ‘cause’ depression have been equivocal. Again, clinicians will be aware that some patients on medications such as haloperidol report a lowering of mood, which is ameliorated when the agent is switched to one of the newer ‘atypical’ antipsychotics. The exact mechanism here is unclear but could be a result of removal of a ‘tight’ and specific dopamine D2-binding agent, resulting in direct effects on mood or secondary effects via enhanced clarity of cognition and/or amelioration of extrapyramidal side-effects. Whether the atypical agents are themselves antidepressive is another matter (see below).

Differentiating depression from psychotic symptoms

Depressive symptoms have been found to be prominent in the prodromal phase of psychosis, and worse in people who subsequently make the transition to the first episode of schizophrenia (Reference UpthegroveUpthegrove 2009). Reference Upthegrove, Birchwood and RossUpthegrove and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that depression can be seen in the vast majority of patients with first-episode psychosis as well as over the later course of the illness (prodrome, acute phase and long-term follow-up). Moreover, their study also found that depression in the prodromal phase was the most significant predictor of future depression and self-harm.

As alluded to earlier, one of the problems of depression in schizophrenia is that symptoms of each might be mistaken for the other. This is particularly apposite when differentiating depressive symptoms from negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Indeed, Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and WagmanCarpenter and colleagues (1988) have pointed out the importance of being aware that observed negative symptoms may be ‘secondary’, as opposed to the primary, core negative symptoms of apathetic withdrawal, restriction of affect and paucity of thought (Table 1). Thus, negative-like symptoms can be caused by typical antipsychotics (so-called neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome; Reference LewanderLewander 1994), by positive symptoms and, pertinent to this discourse, by depression (and, for that matter, anxiety). This distinction is vital as it has profound clinical implications. For example, primary negative symptoms are strongly associated with disability in vocational and other domains, and are notoriously difficult to treat: possibly only clozapine (Reference Essali, Al-Haj and LiEssali 2009) and low-dose amisulpride (Reference Storosum, Elferink and van ZwietenStorosum 2002) have reasonably consistent effects. On the other hand, negative-like symptoms secondary to typical antipsychotics may be alleviated either by a dose reduction or by switching to an atypical agent; such symptoms secondary to positive symptoms may require a different strategy; and depression warrants treatment in its own right, as detailed below.

TABLE 1 Causes and treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia

Low mood and blunted affect

In clinical practice, a number of pointers can help to distinguish depression from negative symptoms. It should be noted that the usual reliance on patients with depression expressing low mood can break down in those with schizophrenia, as they might find it difficult to express how they ‘feel inside’. Perhaps a more useful question is that related to interest in things around them. In depression, individuals usually describe a clear shift from their usual level of interest and also regret or even anguish that they have lost their interests. In contrast, people with negative-symptom schizophrenia mostly talk of interests in a bland and affectless manner, and this tends to be their enduring long-term pattern of relating to the world around them. Eliciting feelings of guilt, hopelessness and suicidality can also help differentiate depression as well as informing risk assessment.

Melancholic features

Other useful indicators of depression include melancholic features such as poor sleep and appetite change. One needs to be aware that people with schizophrenia often have perturbed sleep–wake cycles (e.g. staying up late at night and sleeping during the day) and that some antipsychotics can cause sedation, appetite stimulation and weight gain.

Rating scales

All these factors make established depression rating scales of limited use in schizophrenia. Nevertheless, two scales warrant special mention. First, the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan and McKenneyKirkpatrick 1989) seeks specifically to differentiate primary from secondary depressive symptoms. It comprises six items and includes both interview questions and observational items.

Second, and perhaps of more obvious clinical utility, is the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS; Reference Addington, Addington and SchisselAddington 1990), which was designed specifically to measure depression in people with schizophrenia. This scale is helpful in complementing clinical assessment in differentiating depression from negative symptoms and medication effects in schizophrenia (Reference UpthegroveUpthegrove 2009). There is an emphasis on features such as anhedonia and guilt, and it includes two melancholic items and one suicide item. Each item is scored 0–3, and a cut-off score of 7 is indicative of clinically relevant depression. Box 2 shows the main domains assessed.

BOX 2 Domains covered by the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia

-

• Depressed mood

-

• Hopelessness

-

• Self-deprecation

-

• Guilty ideas of reference

-

• Pathological guilt

-

• Morning depression

-

• Early wakening

-

• Suicidality

-

• Observed depression

Management

In a patient with schizophrenia who presents with depressive symptoms, it is important to investigate organic factors such as substance misuse and endocrine and other medical problems which might be causal or at least contributory. Often people with schizophrenia have medical problems that are not fully investigated or treated, and depression may be a signal of factors such as thyroid dysfunction or cancer. As outlined earlier, it is also important to ask about prescribed medications, as these may cause depressive symptoms.

Risk assessment is critical in all cases, because depression is associated with suicidality and it is well known that suicide is a leading cause of death among individuals with schizophrenia. Although self-harm is common in all phases of first-episode psychosis, it is most likely in the pretreatment phase (the period of untreated psychosis) (Reference Barrett, Sundet and FaerdenBarrett 2010; Reference Upthegrove, Birchwood and RossUpthegrove 2010). Other risks, such as self-neglect, also need to be explored, as many people with schizophrenia are socially isolated and thus do not have significant others caring for or monitoring them.

Psychosocial parameters

As with any patient with depression, assessment and management of broader psychosocial parameters must be part of a comprehensive management plan. In individuals with schizophrenia, where social dislocation, estrangement from family, lack of employment, poor housing and low income are the norm rather than the exception, such strategies are even more important. People with schizophrenia may also need help coming to terms with their illness and dealing with the stigma it carries. Demoralisation can be part and parcel of the picture and needs particular attention.

Despite a massive literature on the role of psychological therapies such as cognitive–behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy in depression, and an emerging literature on application of such interventions for people with schizophrenia (targeting positive psychotic symptoms primarily), there is a dearth of methodologically robust studies reporting the efficacy of psychological treatments for depression in schizophrenia. Most studies have assessed depression as a secondary or tertiary outcome measure and have often not employed well-validated mood rating scales. Studies that have reported mood change with psychological treatments in schizophrenia have generally reported favourable trends. For example, in a meta-analysis including 1297 patients with schizophrenia, Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al (2002) found that cognitive–behavioural therapy was associated with beneficial effects for psychotic symptoms and for depression, and that these effects endured over the 18-month follow-up. Thus, this is a promising area, but one that needs further study, using schizophrenia samples with depression (to enhance power to detect change) and/or specifically addressing depressed mood in patients with schizophrenia.

Pharmacological aspects

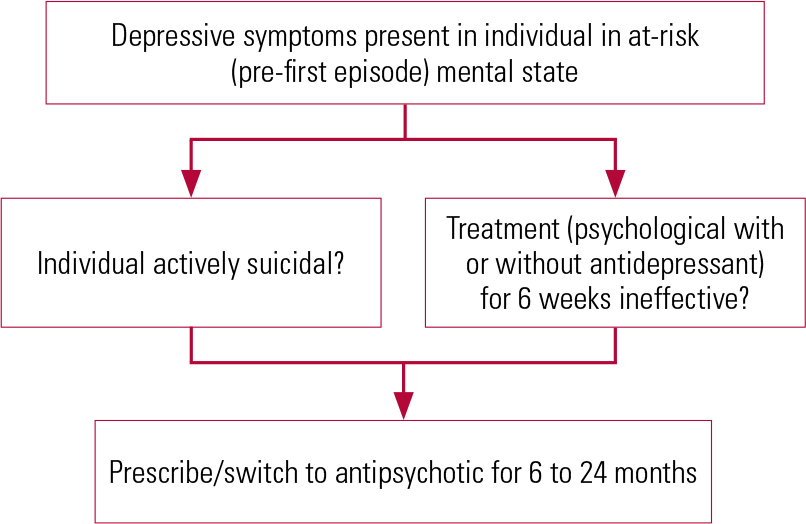

The international clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis (International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group 2005) endorse the use of the minimum effective dose of second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics in preference to first-generation (typical) antipsychotics, in tandem with ‘phase-specific’ treatment of early psychosis. These guidelines also recommend that treatment be offered for depressive syndromes in young people in an ‘at risk’ (for early psychosis) mental state, who are actively seeking treatment and who are distressed or disabled as a consequence of their symptoms. Although the guidelines do not advocate treatment with atypical antipsychotics unless a DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) or ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1992) psychotic disorder is present, they endorse a time-limited therapeutic trial (6 months to 2 years, contingent on response within the initial 6 weeks) in the case of severe suicidality or where the treatment of depression has not been effective (Fig. 1). In addition, the guidelines support a similar approach for as much as 5 years after a first episode: i.e., that an atypical be tried for depression that does not respond to antidepressants or psychotherapy.

FIG 1 Treatment of depressive syndromes in the prodrome (at-risk) period.

Although reduction of the duration of untreated psychosis and treatment of depression during the early phase of the illness is likely to be integral to addressing the risk of suicide (Reference Upthegrove, Birchwood and RossUpthegrove 2010), the literature on the efficacy or otherwise of pharmacological interventions for depression in schizophrenia in general, and in specific phases such as pretreatment, prodrome, acute or follow-up, is scarce and suffers from a number of fundamental problems, outlined in Box 3.

BOX 3 Methodological problems in assessing antidepressant effects in schizophrenia studies

-

• Low power: studies not ‘enriched’ for depression

-

• Severe depression or suicidality often an exclusion criterion

-

• Substance misuse often an exclusion criterion, leading to bias

-

• Reliance on measures of depression that are not optimal in people with schizophrenia

-

• Lack of appreciation of confounding effects of antipsychotic medications on factors such as sleep and appetite

-

• Lack of statistical control for secondary pathways such as alleviation of psychotic symptoms or extrapyramidal side-effects

Given these general caveats, two major pharmacological issues need to be addressed. First, how effective are antidepressants in people with schizophrenia? And second, do the atypical antipsychotics have inherent antidepressant properties?

The role of antidepressants

Regarding the use of antidepressants in schizophrenia, most of the (few) studies were only short term. In their review of the literature, Reference Siris, Bench, Hirsch and WeinbergerSiris & Bench (2003) reported 13 randomised placebo-controlled trials where antidepressants were added to antipsychotics: all but 2 studies used tricyclic antidepressants (the 2 used sertraline). Of these 13 trials, only 4 were positive on the primary outcome measure: one of amitriptyline added to perphenazine (Reference Prusoff, Williams and WeismannPrusoff 1979); one of imipramine to fluphenazine (with benztropine) (Reference Siris, Bermanzohn and MasonSiris 1994); one of fluoxetine to a typical depot antipsychotic (Reference Goff, Brotman and WaitesGoff 1990); and one of sertraline to a ‘stable antipsychotic’ (Reference Cooper, Mulholland and LynchCooper 2000). In a Cochrane review (Reference Furtado, Srihari and KumarFurtado 2008), 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included, with a total of 470 patients. The authors pointed out the low number of participants in many trials and other design flaws, and concluded that ‘At present, there is no convincing evidence either to support or refute the use of antidepressants in treating depression in people with schizophrenia’.

An RCT which added flexibly dosed citalopram to antipsychotic medication for up to 12 weeks in middle-aged and older out-patients with schizophrenia found a reduction in suicidal ideation, when present at baseline, particularly in patients whose depressive symptoms were responsive to this treatment (Reference Zisook, Kasckow and LanouetteZisook 2010).

Longer-term studies are even thinner on the ground. Reference Siris, Bermanzohn and MasonSiris et al (1994) stabilised patients with comorbid schizophrenia and depression on a combination of fluphenazine (with benztropine) and imipramine, then either withdrew the imipramine or continued it for a year. In patients in whom the antidepressant was continued, there were fewer depressive relapses. However, in a naturalistic study of patients with schizophrenia and broadly defined depression treated mostly with atypical antipsychotics and non-tricyclic antidepressants, Reference Glick, Pham and DavisGlick et al (2006) found that in 22 patients in whom the antidepressant was ceased, 18 experienced no significant mood change, 3 showed improvement in their depression, and in only 1 patient did the depression worsen. In a subsequent reflection on these and Siris et al ’s data, Reference Glick, Siris and DavisGlick and colleagues (2008) stated, ‘We believe that for patients with chronic schizophrenia and moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (and/or demoralisation) there may be some who might benefit from an antidepressant’; they give no guidance as to who those ‘some’ might be.

Thus, it is fair to conclude that there are hardly grounds for a ringing endorsement of the use of antidepressants in people with schizophrenia, albeit that they remain widely used in clinical practice and it does seem that, as opined by Reference Glick, Siris and DavisGlick et al (2008), ‘some’ patients do benefit. Who those ‘some’ are is an open question, but most data are for full syndromal depression. One would also assume that antidepressants would be more likely to be indicated in more severe depression, and certainly in depression with melancholic features and/or suicidality.

Another factor is the potential for drug–drug interactions (e.g. fluvoxamine raises levels of clozapine dramatically, through its effect on the cytochrome P450 1A2 pathway) and exacerbation of side-effects of the prescribed antipsychotic. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors can have akathisic-like effects and are associated with sexual side-effects; and mirtazapine can cause somnolence and weight gain. In the light of this, one needs to consider the potential negative impact on medication adherence associated with polypharmacy.

Are atypical antipsychotics also antidepressants?

Many claims have been made for the superiority of atypical antipsychotics over the typical agents, including lower extrapyramidal side-effect burden, enhanced efficacy for negative symptoms, cognitive benefits and antidepressant efficacy. These factors are not mutually exclusive as, for example, a reduction in extrapyramidal side-effects would be expected to be associated with lower secondary negative symptom burden; and feeling less cognitively slowed could arguably enhance mood. Thus, any true test of whether atypical antipsychotics are antidepressive needs to accommodate these potential pathways: this has been done in only a few studies, as outlined below.

One could argue that demonstrable anti-depressant effects of certain antipsychotics in bipolar depression and major depressive disorder would suggest that they would be beneficial for depression in schizophrenia. Notably, quetiapine (Reference Calabrese, Keck and MacfaddenCalabrese 2005; Reference Thase, Macfadden and WeislerThase 2006; Reference Suppes, Datto and MinkwitzSuppes 2009) and olanzapine (Reference Tohen, Vieta and CalabreseTohen 2003; Reference Vieta, Locklear and GunterVieta 2010) have been successful for bipolar depression, while for major depressive disorder, quetiapine has been efficacious as a solo agent (Reference Cutler, Montgomery and FeifelCutler 2009; Reference McIntyre, Muzina and AdamsMcIntyre 2009; Reference Weisler, Joyce and McGillWeisler 2009) and as an adjunct to antidepressants (Reference Dannlowski, Baune and BöckermannDannlowski 2008), as has aripiprazole as an adjunct in major depressive disorder (Reference Papakostas, Petersen and KinrysPapakostas 2005; Reference Patkar, Peindl and MagoPatkar 2006; Reference Rutherford, Sneed and MiyazakiRutherford 2007; Reference Schwartz, Nasra and ChiltonSchwartz 2007; Reference Arbaizar, Dierssen-Sotos and Gomez-AceboArbaizar 2009; Reference Berman, Fava and ThaseBerman 2009; Reference Steffens, Nelson and EudiconeSteffens 2011) and bipolar disorder (Reference Kemp, Gilmer and FleckKemp 2007; Reference SokolskiSokolski 2007; Reference Arbaizar, Dierssen-Sotos and Gomez-AceboArbaizar 2009). But such assumptions might not be supportable, given the complexity of schizophrenia, including its differential and multifactorial aetiology and epiphenomena.

However, few methodologically robust studies have directly assessed the effects of atypical antipsychotics on depression in people with schizophrenia. This is in part because of the difficulties outlined in Box 3. Noting these caveats, Table 2 provides a synopsis of the main studies of atypical antipsychotics for depression in schizophrenia.

TABLE 2 Summary of atypical antidepressant efficacy for depression in schizophrenia

A recent review of data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) involving 1460 patients with chronic schizophrenia did not show any difference between atypical antipsychotics and the ‘typical’ comparator perphenazine, on depressive symptoms measured on the CDSS (Reference Addington, Mohamed and RosenheckAddington 2011). In other studies, it will be noted that the most consistent effects are seen for quetiapine and olanzapine. For olanzapine, the study of Reference Tollefson, Beasley and TranTollefson and colleagues (1997) is particularly instructive, as it presents a path analysis suggesting that, after taking account of indirect mood effects such as amelioration of positive symptoms and extrapyramidal side-effects, 57% of the noted mood effects could be considered as a direct antidepressant effect.

Another important finding from this literature is the antisuicide effect associated with clozapine. This has been shown in observational (Reference Meltzer and OkayliMeltzer 1995) and case-register studies (Reference Walker, Lanza and ArellanoWalker 1997) as well as in the landmark International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSepT) comparing olanzapine with clozapine (Reference Meltzer, Alphs and GreenMeltzer 2003). The precise mechanism whereby clozapine reduces suicidality is not fully understood, but presumably amelioration of depressed mood plays a part, and the data should sway clinicians in decisions about when to introduce clozapine in patients with schizophrenia at high risk for suicide.

A treatment framework

In his useful review, Reference SirisSiris (2000) suggests a pragmatic treatment framework for depression in schizophrenia (Fig. 2). For the treatment of established syndromal depression in people with schizophrenia, we suggest:

FIG 2 Framework for the pharmacological treatment of depression in schizophrenia if symptoms persist on an antipsychotic.

-

1 treat the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia as effectively as possible as a priority, then ‘see what is left’ in terms of mood symptoms; certainly, do not treat too quickly with antidepressants;

-

2 address psychological and social issues, reinforcing the rehabilitation/recovery approach to treatment;

-

3 implement appropriate evidence-based psychological therapies;

-

4 consider using antipsychotics with established antidepressive properties;

-

5 if antidepressants are required, use those with lower propensity to side-effects and drug–drug interactions.

Conclusions

Depression is common in and often integral to schizophrenia throughout its course. In many ways this is understandable, given the nature of schizophrenia and the impact it has on the lives of individuals. In clinical practice, depression is often be overlooked because its symptoms and signs are mistaken for products of schizophrenia itself, or the right questions are not asked in the right way. It is incumbent upon clinicians to be alert to the possibility of depression in patients with schizophrenia (especially in the early phase of schizophrenia, when the potential to mitigate suicide risk is particularly high) and to manage it using a comprehensive biopsychosocial approach. In terms of medication, some a typical antipsychotics do seem to have primary antidepressant effects and this should inform clinical choice of agent in patients presenting with, or with a particular propensity towards, depression.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Depressive symptoms in people with schizophrenia:

-

a occur infrequently

-

b are easily separated from core symptoms of schizophrenia

-

c are rarely missed

-

d are adequately described by current classification systems (e.g. DSM and ICD)

-

e can cause significant distress and burden even when full syndromal criteria are not met.

-

-

2 With regard to schizoaffective disorder:

-

a there are broad diagnostic criteria in current classification systems

-

b the first operationalised diagnostic criteria were implemented at the time of the DSM-III in 1980

-

c this was originally described by Kraepelin

-

d a symptom-based therapeutic approach may be useful clinically

-

e DSM does not require a full affective syndrome for diagnosis.

-

-

3 With regard to treating depressive symptoms in schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics:

-

a all atypicals are generally useful and similar in efficacy

-

b olanzapine and quetiapine have the least consistent effects

-

c clozapine has an antisuicide effect

-

d most studies are methodologically robust and have consistent comparators and outcome measures

-

e studies generally take into account the impact of extrapyramidal symptoms and cognitive functioning on mood.

-

-

4 In the pharmacological treatment of depression in schizophrenia, it is not helpful to:

-

a exclude organic or general medical factors

-

b explore stressors or prodromal symptoms

-

c increase the antipsychotic dose if depressive symptoms persist

-

d treat extrapyramidal side-effects

-

e consider augmentation with lithium or electro-convulsive therapy.

-

-

5 In treating established syndromal depression in schizophrenia, it may be helpful to:

-

a introduce antidepressant medication early, irrespective of positive and negative symptoms

-

b address psychological and social issues, with reinforcement of the rehabilitation/recovery approach

-

c use any antipsychotic medication, as all are similar in antidepressant properties

-

d use any psychological intervention, without the need for considering the evidence base

-

e use any antidepressant medication, as all are similar in side-effect profile and drug–drug interactions.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | d | 3 | c | 4 | c | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.