The ability of doctors to provide calm encouragement and reassurance for benign, self-limiting illness has always been a key component of medical care. It is appropriate for individuals to monitor their own symptoms, seek information and attend experts when unwell. However, when such behaviours become excessive in terms of frequency, duration or impact they become a problem and can result in unintended, potentially negative consequences.

What is excessive reassurance-seeking?

Excessive reassurance-seeking is common and can worsen symptoms in a range of anxiety and mood disorders. The aim is often to prevent catastrophe and reduce harm, tension and distress (Reference SalkovskisSalkovskis 1985). It includes excessively seeking medical care, internet-searching, checking bodily symptoms or using hidden cognitive reassurance such as covert counting in obsessive–compulsive disorder.

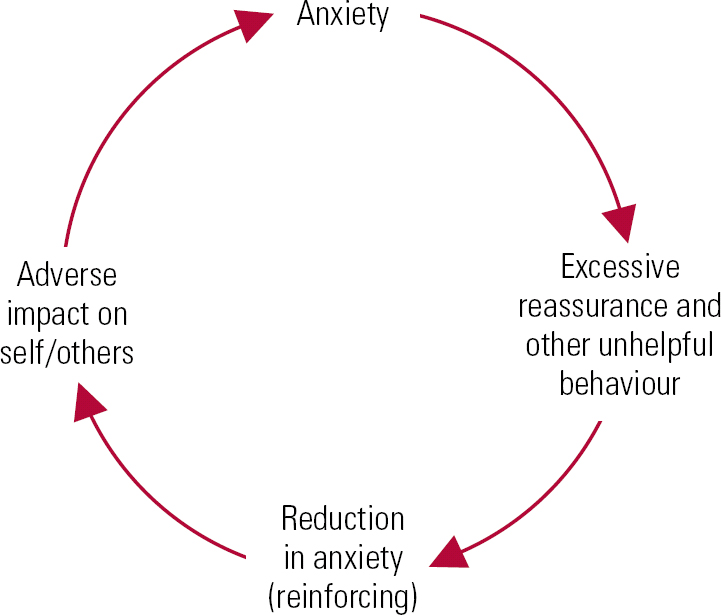

Excessive reassurance-seeking is addictive. It quickly diminishes anxiety, leading to immediate relief. However, the relief does not last and reassurance-seeking returns. This backfires because it strengthens the belief that, had reassurance not been sought, anxiety may have increased and the feared consequence occurred. Thus, the behaviour is reinforced. Reassurance-seeking is self-perpetuating, as no empirical evidence against the occurrence of what was feared is observed.

Excessive reassurance-seeking across disorders

In social anxiety and panic there are overlaps between anxiety, reassurance- and safety-seeking behaviours. So, someone with a fear of incontinence linked to panic may wish to reassure themselves by always knowing the location of toilets, and may recurrently empty their bladder even when not needed. In panic, self-checking can occur for flushing, heart rate, breathing, sweatiness and tremor. The checking itself exacerbates symptoms.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder behaviours such as counting, checking or cleaning occur as a form of self-reassurance that the feared consequence can be avoided or minimised. Excessive reassurance-seeking can be covert and hidden (counting/praying) as well as overt such as recurrently asking others for reassurance that the feared consequence has not occurred.

In health anxiety and dysmorphophobia, the focus of anxiety is inward-looking (with body-checking, mirror-gazing) or overt (with opinion-seeking from others). Diaries of physiological measures such as blood pressure, temperature and heart rate may be brought to professionals, as well as requests for examination (e.g. ‘Has this lump changed?’) or other similar reassurance-seeking comments (e.g. ‘Do I look pale?’).

In depression, similar to social anxiety, the focus is often on checking doubts that others judge the person negatively and on personal performance. Individuals seek opinions from others to check views of themselves, their work or performance.

Why is excessive reassurance-seeking unhelpful?

Excessive reassurance-seeking is driven by anxiety and acts to worsen and perpetuate it. This can cause personal and carer exhaustion, present challenges to the practitioner–patient relationship and result in unnecessary referrals, investigations, procedures or discharge.

What can we do about it?

Excessive reassurance-seeking is addressed with exposure and response prevention. This involves repeatedly facing the fear and choosing not to seek reassurance (i.e. not to check, measure, ask, review, do). Exposure can be paced to slowly and purposively help the person reduce the reassurance-seeking. Anxiety levels will eventually fall and the individual learns that reassurance-seeking is not needed to reduce anxiety, the feared outcome does not occur and that they have power over their thoughts and actions.

The principles can be applied to everyday psychiatric practice in three steps below, drawn from the Amazing Bad Thought Busting Programme (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2007).

Label it

Educate your patients in differentiating between innocuous and pathological reassurance. When is it backfiring and making them feel worse? A vicious circle model (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2012) can illustrate the unhelpfulness of excessive reassurance-seeking (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Brief reduction in anxiety (reinforcing excessive reassurance-seeking). Irrespective of the short-term improvement in anxiety (which is highly reinforcing), the underlying fears are left unchanged and the behaviours fail to extinguish. Excessive reassurance-seeking serves to alleviate anxiety in the short term, at the expense of perpetuating or worsening an individual's difficulties in the long term. (After Reference WilliamsWilliams 2012.)

Leave it

Once labelled, ask the patient to not collude with it – just let it be; do not get caught up in it. Instead, attend to the here and now.

Stand up to it

Like a bully, excessive reassurance-seeking shouts out and tries to force its way into people's lives. Encourage patients to face up to the bully and call its bluff; do not respond and see what occurs. The purpose of exposure and response prevention is to expose one's self to the anxiety-provoking stimulus, await reduction in anxiety over the short term and in the long term habituate one's self to that stimulus.

What if things prove difficult?

Cognitive–behavioural approaches provide a framework for engagement and work. However, sometimes patients fail to engage, are not motivated to change or wish to avoid the costs of facing anxiety. Two key strategies can help. The first is to help people work out how the vicious circle is causing their symptoms to stick. Understanding will often lead to motivation and belief in the possibility of change. The second, if stuck, is to review other factors – behaviours of others, the need for concurrent medication, a focus on other maintaining factors such as low mood – and ensure that each step of treatment is agreed, slowly, with no surprises, yet sufficiently pushes the person to face their fears and move things along. Sometimes people are not ready for change – in which case a discussion about leaving things as they are is an option for them – but they will continue to live with the costs of anxiety unless they choose at some stage to work at change.

Conclusions

Exploration of meaning behind reassurance-seeking thoughts and behaviours can help practitioners and patients differentiate between helpful and unhelpful reassurance-seeking strategies, with simple patient education and formulation building a sound foundation from which an exposure and response prevention plan can be created.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.