Intoxication with alcohol or drugs is the obvious theme of certain charges such as drunk and disorderly conduct or drink-driving. In other offences, intoxication may be a factor that can affect or complicate the issue of criminal responsibility.

Approximately 50% of violent offences and property offences are committed after drugs or alcohol have been consumed, and although consumption may not be directly linked to the offence, there is often a strong association between the two.

Psychiatrists are frequently asked to comment on the effects of intoxication on mental responsibility. Although the legal defences of insanity and diminished responsibility are familiar to psychiatrists, the relationship between intoxication and criminal intent is a complex issue that can raise the possibility of defences against particular offences. This paper will mainly consider the law in England and Wales. The major differences in the legislation of the other jurisdictions in the UK are given in Box 1.

Box 1 Other UK jurisdictions

The law in Scotland attaches rather less importance to subjective mens rea than that in England and Wales. Most Scottish criminal charges allege no mental element at all but refer only to the proscribed harm. The mens rea terms such as recklessness and negligence are often interpreted with an objectivist slant. Liability for causing inadvertent harm while drunk departs little from normal principles. The distinction between offences of basic and specific intent has therefore not developed to the same extent as south of the border. For example, in Brennan v HM Adv. [1977], the accused stabbed his father to death after consuming between 20 and 25 pints of beer together with lysergic acid diethyamide (LSD). He was convicted of murder and his appeal was dismissed: voluntary intoxication was considered to be a continuing element of criminal recklessness which Scottish law needed to retain in the interests of its citizens.

Similar positions are held in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Although the Beard rules ( DPP v Beard, 1920) have never been overruled, voluntary intoxication does not provide the basis for a defence to criminal charges.

The issues surrounding intoxication and legal defence appear to be addressed in a variety of ways, which might reflect the complexity of the legal arguments. The law has arisen as a ‘compromise’ between acknowledging the effects of alcohol and drugs on mental condition and maintaining criminal liability, for the benefit of society. These are areas into which the psychiatrist often strays and may even introduce his own moral code. The legal issues that psychiatrists should be aware of when considering such a venture are outlined below.

There is a generally held belief that many of the legal issues in this area are centred around a theme of intoxication. This is ill-founded and opinions may be sought about the effects of alcohol and drugs without reliable indices of actual intake. The law is less concerned with more-modest and minor consumption, although clinicians are often aware of individual variability and the hazards of estimating consumed quantity from the appearance and behaviour of the defendant at the time of the offence.

The law pays little attention to the claim of individuals that they had a drink in order to ‘remove their inhibitions’. It is seen as irrelevant that the individual would not have committed the crime if he had not had a drink: he is seen as being fully responsible at the time of the offence. The law is, however, applicable when the person is so intoxicated as to lack the state of mind required in relation to that crime (the mens rea) or to be in a state of automatism. It is not a matter as to whether the defendant was capable of forming mens rea. It is a question of whether mens rea was, in fact, formed.

Case law has been described for the following circumstances:

-

(a) intent – specific and basic

-

(b) intoxication – involuntary and voluntary

-

(c) voluntary intoxication and offences of basic intent

-

(d) partial intoxication

-

(e) intoxication and mistake

-

(f) voluntary intoxicated beliefs

-

(g) intoxication and mental health defences of:

-

• insanity

-

• diminished responsibility

-

• automatism.

-

Crimes of specific and basic intent

The essence of the law is that intoxication can provide a defence to crimes that are of specific intent, but not to those that are of basic intent. In crimes of specific intent, it must be proved that the defendant lacked the necessary mens rea at the time of the offence. It is for the prosecution to establish the actual intent of the defendant, taking into account the fact that he was intoxicated. In crimes of basic intent, the fact that intoxication was self-induced provides the necessary mens rea.

The original distinction between crimes of specific and of basic intent was based on common sense: the court did not want alcohol to allow a defendant to escape responsibility for his crimes. It did, however, wish to have flexibility so that in certain cases intoxication afforded, in effect, some mitigation. The allocation of crimes to the categories of basic or of specific intent is not based on any established legal test and has often arisen from previous court decisions (Reference Smith and HoganSmith & Hogan, 1996). In practice, the terms are difficult to define and are sometimes anomalous. They seem to escape definition; their purpose may be to reduce criminal liability while not allowing the defendant to escape all punishment, but the delineation of crimes into the two categories is less rigorous.

Examples of crimes that have been held to be of specific intent (Box 2) include murder ( R v Sheehan, 1975), wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent ( R v Pordage, 1975), theft ( Ruse v Read, 1949), deception and handling stolen goods ( R v Durante, 1972). Crimes that are held to require only a basic intent (Box 2) include manslaughter ( R v Lipman, 1970), malicious wounding or inflicting grievous bodily harm under section 20 ( Bratty v A-G for Northern Ireland, 1963), rape ( R v Fotheringham, 1989) and various offences of assault.

Box 2 Offences requiring specific or basic intent

Specific intent Basic intent

Murder Manslaughter

Grievous bodily harm with intent Malicious wounding Rape

Theft Grievous bodily harm

Deception under section 20

Handling stolen goods False imprisonment

Voluntary and involuntary intoxication

Voluntary intoxication

Voluntary intoxication refers to the knowing intake of alcohol and/or some other drug or intoxicating substance. The individual must be aware that the substance is, or may be, an intoxicant and have taken it in such a quantity that it impairs his awareness or understanding. The law presumes that intoxication is voluntary unless evidence is produced that allows the court or jury to conclude the possibility that it was involuntary.

Voluntary intoxication is not, and never has been, a defence in itself. It is not a defence to plead that by taking alcohol one's judgement between right and wrong was impaired or that one was no longer able to resist an impulse. There are, however, three broad situations when voluntary intoxication may be forwarded as a defence or mitigating factor and thus be considered as a partial excuse to reduce the level of criminal liability. They are:

-

(a) when intoxication leads to the inability to form the specific intent requisite for a particular offence;

-

(b) where a statute expressly provides a false belief to be a defence to the particular offence;

-

(c) when mental conditions allow the defences of insanity or diminished responsibility.

Involuntary intoxication

The most common cases of involuntary intoxication involve intoxication that is unknowingly induced by a third party. Intoxication can also be held as involuntary if it is caused by prescribed drugs taken within the required instructions of a doctor, or if caused by a drug, whether or not taken in excessive quantity, that is not normally liable to cause unpredictability or aggressiveness (for example sedatives such as benzodiazepines).

Where a defendant is reduced to a state of intoxication through no fault of his own, he cannot be ‘blamed’ for his actions and will, accordingly, have a defence to any criminal charge. The defendant must, however, be so intoxicated that he did not form the requisite mens rea. If the mens rea is thought to be present, then the law approaches such cases in the same way as for voluntary intoxication, in that involuntary intoxication is not, in itself, a defence.

Thus, provided that the defendant acted voluntarily with the requisite mens rea, the fact that involuntary intoxication led the accused to commit an offence that he would not have committed when sober, does not afford a defence (although it may mitigate the punishment), and this is so even though he acted under an irresistible impulse because of intoxication (Box 3).

Box 3 A drugged intent is still an intent

D, who had paedophiliac homosexual tendencies, was in dispute with a couple who arranged for X to obtain damaging information that could be used against D. X invited a 15-year-old boy to his room and drugged him so that he fell asleep. While he was asleep, D visited X's room and indulged in indecent acts on the boy. These were videorecorded by X. D was charged with indecent assault on the boy. His defence was that he had been involuntarily intoxicated at the time because X had laced his drink. He was convicted.

Judgement: the trial judge directed the jury to convict if they found that D had assaulted the boy pursuant to an intent resulting from the influence of intoxication secretly induced by X. Acquittal would arise only if he was so intoxicated, involuntarily, that he did not intend to commit the indecent assault (a basic intent offence). This ruling was held by the House of Lords on appeal.

R v Kingston [1994]

Voluntary intoxication and crimes of specific intent

In case law, the meaning of specific intent has been clarified by Lord Birkenhead's decision of 1920 in the case of Beard who, when intoxicated with alcohol, suffocated a girl while raping her ( DPP v Beard, 1920). From this case, ‘insanity’, whether produced by drunkenness or otherwise, is a defence against the criminal charge. An accused man could therefore be declared not guilty if intoxication rendered him incapable of forming the specific intent for that offence. According to the Beard rules:

‘In a charge of murder based upon intention to kill or do grievous bodily harm, if the jury are satisfied that the accused was, by reason of his drunken condition, incapable of forming the intent to kill or do grievous bodily harm… he cannot be convicted of murder. But nevertheless, unlawful homicide has been committed by the accused… and that is manslaughter … The law is plain beyond question that in cases falling short of insanity a condition of drunkenness at the time of committing an offence causing death can only, when it is available at all, have the effect of reducing the crime from murder to manslaughter.’

It has been argued that these rules are based on judicial policy to protect the public against the prospect of absolute acquittal. This view could be taken further to suggest that such a policy is imperfect; for example, rape is not a crime requiring specific intent and theft has, unlike murder, no charge of basic intent to fall back on. The law changed somewhat following the introduction of the 1967 Criminal Justice Act. Section 8 of the Act no longer stipulates that incapacity is requisite in the proof of lack of specific intent. Also, under section 8, individuals are no longer presumed to intend the natural and probable consequences of their acts; rather, necessary intent is to be decided by the jury or magistrates on all the available evidence. Contradictory to the ruling in the Beard case, it is now established that the burden is on the prosecution to establish that, despite the evidence of intoxication, the accused had the necessary specific intent.

Voluntary intoxication and crimes of basic intent

For crimes that require only basic intent, intoxication is no defence. The case law is affirmed in DPP v Majewski [1976]. The accused had taken barbiturates, amphetamines and alcohol and subsequently assaulted a publican and three policemen. He was convicted of assault and his following appeal was dismissed.

The judgement from Majewski was that, if the offence charged is one of basic intent, the accused may be convicted of it if he was voluntarily intoxicated at the time of committing the offence, even though, because of intoxication, he did not have the mens rea normally required for the conviction of that offence, and despite the fact that he was in a state of automatism. Additionally, the House of Lords recognised in Majewski that, for a person charged with an offence of basic intent, the prosecution does not need to prove the mens rea required for that offence and the accused can be convicted simply on proof that he committed the offence (the actus reus).

This leads on to the complex concept of recklessness. Certain crimes, such as attempted murder, can only be committed intentionally; others may be committed recklessly. The distinction is important. A distinction must also exist between recklessness and negligence, so that the law can punish reckless wrongdoing, but, apart from certain crimes, it can exempt negligent wrongdoing from criminal liability.

The type of recklessness recognised by the majority of the House of Lords is termed ‘Caldwell-type’ recklessness following their Lordships’ decision in R v Caldwell [1982]. An individual is Caldwell-type reckless with regard to a particular risk that attends his actions if the risk is obvious to an ordinary prudent person who has not given thought to the possibility of there being any such risk, or if the individual has recognised that there is some risk and has nevertheless persisted in his actions.

The effect of the ruling in Majewski that proof of mens rea is not required when an accused who is voluntarily intoxicated is charged with an offence of basic intent is reduced when Caldwell-type recklessness suffices for that offence. In R v Caldwell, Lord Diplock took the view that classification of offences into those of basic or specific intent was irrelevant where Caldwell-type recklessness sufficed for mens rea. The distinction between such offences is important, however, if the intoxicated person who is charged with an offence of basic intent has thought about a possible risk and wrongly concluded it to be negligible. In this case, a loophole in Caldwell-type recklessness (termed ‘the lacuna’) means that he could not be convicted of recklessness. Indeed, he would be acquitted unless convicted under the Majewski ruling on the basis that the actus reus of an offence of basic intent has been committed.

Drug-induced intoxication and intent

Theoretically, the same rules apply to intoxication with drugs. In R v Lipman [1969], the accused, in a state of intoxication caused primarily by lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), asphyxiated a girl by forcing a bedsheet down her throat while believing that he was struggling with snakes. He was deemed to have been reckless, but his state of intoxication rendered him incapable of forming the specific intent for murder and he was therefore convicted of manslaughter.

Intoxication and rape

Rape is a crime of basic intent: the central theme of the charge of rape is one of consent. In the case of R v Woods [1981], the accused pleaded that he was so drunk that he had not realised that his victim had not provided consent. Section 1(2) of the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1976 states that if a jury has to consider whether a man believed that a victim was consenting to sexual intercourse, it must have regard to the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for such a belief, in conjunction with any other relevant matters. The Court of Appeal held that intoxication was not a ‘legally relevant matter’ in this context and therefore the jury must examine the other evidence and disregard the evidence of his intoxication.

Partial intoxication

There is no legal distinction between being completely or partially intoxicated if a defence of intoxication is raised. The ruling from Majewski would therefore apply to partial intoxication in offences requiring a basic intent.

Intoxication and mistake

Intoxication has many effects, including the misinterpretation of the actions and words of others. In many cases, a defendant who committed a crime when drunk will claim that he made a mistake: therefore the necessary mens rea was lacking.

If a sober person kills another in the mistaken belief that the victim is coming towards him to stab him, he may be found not guilty of murder (provided that he used force that was reasonable on the basis of the facts as he believed them to have been) because he lacked an intent to kill unlawfully or cause grievous bodily harm. Where, however, the mistake arises by reason of voluntary intoxication, the Majewski principle applies, so that the defendant cannot rely on his mistake to acquit him of the crime.

Recent case law suggests that the Majewski ruling applies in this context even if the offence is one of specific intent. In R v O'Grady [1987], the defendant, when intoxicated, killed a man in the mistaken belief that he was being attacked. His appeal against his conviction for manslaughter, an offence of basic intent, was dismissed by the Court of Appeal. Lord Lane judged that a defence of mistake caused by voluntary intoxication would fail even in offences that required specific intent.

Dutch courage

On occasion, individuals use alcohol or drugs to make it easier for them to take certain actions, including criminal ones. The law has ruled that with such offences (including those of specific intent), one is liable, even if, because intoxicated, one lacks the appropriate mental element at the time of the offence. According to Lord Denning's interpretation of the Court of Appeal's decision in A-G for Northern Ireland v. Gallagher [1963]:

‘… if a man, whilst sane and sober, forms an intention to kill and makes preparations for it, knowing it is the wrong thing to do, and then gets himself drunk so as to give himself Dutch courage to do the thing, and whilst drunk carries out his intention, he cannot rely on this self-induced drunkenness as a defence to a charge of murder, nor even as reducing it to manslaughter. He cannot say that he got himself into such a stupid state that he was incapable of an intent to kill. So, also, when he is a psychopath, he cannot by drinking rely on his self-induced defect of reason as a defence of insanity. The wickedness of his mind before he got drunk is enough to condemn him, coupled with the act which he intended to do and did do. A psychopath who goes out intending to kill, knowing it is wrong, and does kill, cannot escape the consequences of making himself drunk before doing it.’

Intoxicated belief as a defence

There is one type of case where an intoxicated belief can be used as a defence. In Jaggard v Dickinson [1980, 1981], the accused was allowed to appeal against conviction of intentional or reckless criminal damage to property. The accused, owing to voluntary intoxication, mistakenly but honestly believed that she was damaging the property of a friend and that the latter would have consented to her doing so. Section 5(3) of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 states that a belief of entitlement to consent to the destruction of property is a lawful excuse and it is immaterial whether such a belief is justified or not, if it is honestly held.

Intoxication and mental health defences

Insanity, diminished responsibility and automatism are mental condition defences within the criminal law of England and Wales. They are not specific to intoxication-related defences.

Insanity

Ever since their inception in 1943, the M'Naghten rules (Reference MackayMackay, 1995) have been the standard test of criminal responsibility when applied to the defence of insanity. Mackay states that:

‘To establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong. “Disease of the mind” is a wide-ranging concept which is capable of encompassing all forms of mental disorder which give rise to a ‘defect of reason’. The courts tend have a narrower interpretation of ‘knowledge’ requirements of the rules, that is, “nature”, “quality” and “wrong”. The lack of knowledge of these elements when committing a criminal act is restricted to the lack of legal rather than moral knowledge. The courts therefore apply an extremely restricted approach to the rules which is cognitively, rather than morally, based.’

Therefore, intoxication can satisfy the legal definition of insanity only if the associated state of mind satisfies the strict legal interpretations of disease of the mind and defect of reason. Certain states, such as delirium tremens or drug-induced psychosis, may satisfy all of these criteria. It is also worth noting that if the defendant's state of mind results partly from drink or drugs and partly from a condition that is capable of forming the insanity defence in its own right (e.g. psychopathy), intoxication is usually disregarded as a defence unless it has induced the latter condition within the meaning of the M'Naghten rules.

Diminished responsibility

The defence of diminished responsibility, under section 2 of the Homicide Act 1957, is available for the charge of murder only. There are three components to the defence:

-

(a) that the accused was suffering from an abnormality of mind at the material time;

-

(b) that this arose from:

-

• a condition of arrested or retarded development of mind;

-

• inherent causes;

-

• the result of disease or injury;

-

-

(c) that it substantially impaired his mental responsibility on such acts as willpower, perception and judgement.

Alcohol consumption can therefore find a defence of diminished responsibility if alcoholism has amounted to ‘disease or injury’. A defence of diminished responsibility cannot, however, be based on an abnormality of mind brought about by voluntary intoxication, as this has not arisen from any inherent causes or been induced by disease or injury. The Court of Appeal has consistently ruled that the transient effects of alcohol on the brain do not amount to injury within the meaning of section 2(1) of the Homicide Act 1957.

For alcoholism to amount to disease or injury, the psychiatrist will have to consider whether cerebral damage has injured the brain to such an extent that there is a gross impairment of judgement and emotional responses. The appropriate physical investigations, such as neuroimaging, electroencephalograms and psychometric testing, may be of value in supporting this defence.

If alcoholism has not led to extensive brain damage, a defence of diminished responsibility may still be available if drinking has become involuntary. Alcohol dependence could therefore theoretically support such a defence, but existing case law (see Box 4) imposes strict criteria. The legal test for such a loss of control, or inability to resist the impulse to drink, requires that the first drink of the day to be completely involuntary. If the accused is able to resist the impulse to take the first drink, he does not suffer from a ‘disease or injury’ within section 2 of the Homicide Act, even if he finds the impulse to continue drinking irresistible. A defence of diminished responsibility cannot then apply.

Box 4 The ‘first drink of the day’ test

The accused, an alcoholic, usually drank barley wine or Cinzano. On the day of the killing, she drank almost an entire bottle of vodka. That evening, she strangled her 11-year-old daughter after the child had said she had been sexually interfered with at home and wanted to live with her grandmother. The mother's blood alcohol level at the time of the killing was estimated to have been 300 mg per 100 ml, which can be fatal to non-alcoholics. The defendant's own evidence had suggested that she still had control over her drinking after the first drink, despite severe craving for alcohol. The jury convicted her of murder, having decided that she did not suffer from an abnormality of mind as a direct result of her alcoholism.

Her appeal was based on the medical evidence that she might have had a compulsion to drink, at least after the first drink of the day, and that the cumulative effects of such consumption had caused an intoxicated state at the time of the killing. Her counsel also argued the possibility that craving for drink and drugs could produce an abnormality of mind. The appeal was dismissed, the jury having been correctly told by the trial judge that if the taking of the first drink was not involuntary, then the whole of the drinking on the day in question was not involuntary. As for severe craving for drink leading to an abnormality of mind, such craving would need to lead to involuntary drinking and would thus be subject to the ‘first drink of the day’ test.

One could argue that the judgement in R v Tandy [1989] could also apply to drug use alone for a defence of diminished responsibility, if the taking of drugs has been involuntary or has resulted in ‘disease or injury to the mind’ such as to substantially impair mental responsibility. At present there is no clear authority on this point (Reference MackayMackay, 1999).

Automatism

A defence to a crime can be made if it was committed involuntarily. Where the involuntary act is beyond the control of the individual's mind, the situation is known as an automatism. In broad terms, there are two types of automatism: insane and non-insane. With automatism of the insane type, if the involuntary act can be shown to have occurred in the context of a ‘defect of reason due to disease of the mind’, the M'Naghten rules and special verdict apply. With automatism of the non-insane type, the accused may be acquitted. In general, therefore, if an act is performed in a state of automatism, criminal liability is negatived.

In some cases, however, such action can be liable under Majewski if that automatic state is the result of voluntary intoxication and the offence is one of basic intent. The position is less clear if intoxication is one of a number of features alleged to have combined to produce an automatic state, for example automatism alleged to have been induced by head injury following intoxication. The current law (Law Commission, 1992) suggests that where causal factors are less-easily separated, it would seem that the presence of intoxication, based on the Majewski ruling, excludes reliance on automatism.

Conclusions

The effect of alcohol on the individual is very complex and idiosyncratic. Psychiatrists making evaluations for the purposes of court reports face further hurdles in trying to untangle the legal arguments. A clinical evaluation that will be of use to the court will require a thorough history of the events, with a special focus on the defendant's account of the event and consumption of intoxicants in the period leading up to the offence. It is also essential to thoroughly tease out the history of alcohol and substance misuse. Clinical assessment may be complicated by amnesia, which is common in serious offences but is not per se a defence in criminal proceedings (Reference Taylor and KopelmanTaylor & Kopelman, 1984).

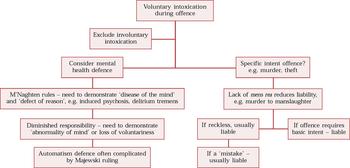

The principal problem when assessing the state of intoxication characterising an offender who has committed a criminal act is that many offenders lack one of the key premises for responsibility for a criminal act, namely mens rea. The judgement of being legally guilty or culpable requires the conversion of legal and philosophical values into working jurisprudence. Case law provides practical guidance when considering issues of legal defences, but it is complex and subject to frequent reform (Reference Fischer and RehmFischer & Rehm, 1998; Reference GoughGough, 2000). Although it is the court process that decides on culpability, it is not unusual for psychiatrists to be asked to comment on specific mental elements related to a criminal offence committed by an intoxicated defendant. Aside from the well-established mental condition defences of insanity and diminished responsibility, a working knowledge of the association between intoxication and intention is therefore helpful (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Legal defences available to the intoxicated offender.

Multiple choice questions

(All questions relate to the law in England and Wales only)

-

1 The following offences require specific intent:

-

a rape

-

b theft

-

c deception

-

d manslaughter

-

e murder.

-

-

2 The following offences require only basic intent:

-

a handling stolen goods

-

b malicious wounding

-

c indecent assault

-

d kidnapping

-

e common assault.

-

-

3 Voluntary intoxication may present as a legal defence if:

-

a the offence requires the presence of a specific intent

-

b the offence requires the presence of a basic intent

-

c the defendant is reckless at the time of the offence

-

d alcohol is consumed for Dutch courage prior to the offence

-

e the defendant's reasons for the offence are based on a mistaken belief.

-

-

4 Intoxication can be held as involuntary if:

-

a it is caused by a prescribed drug taken according to instructions

-

b it is unknowingly administered by a third party

-

c the prescribed drug is not medically reported to cause intoxication

-

d the defendant has underestimated the amount of drugs or alcohol consumed

-

e the defendant has amnesia for the offence.

-

-

5 The following strongly supports a defence of diminished responsibility:

-

a the accused was intoxicated at the time of the killing

-

b alcohol was consumed a priori for Dutch courage

-

c the accused has organic brain damage caused by chronic alcoholism

-

d the defendant has alcohol-dependency syndrome

-

e alcohol consumption is no longer voluntary.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F |

| b | T | b | T | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | F | c | T | c | F |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.