Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care was launched under the auspices of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in December 2002 and immediately widely disseminated to individuals and organisations throughout the National Health Service (NHS). Individuals who received a personal copy included every general practitioner (GP) in England and Wales, the chief executives of every every health care trust and every director of nursing. Community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) received the guidelines through the journal of the CPN Association and service-user groups also received copies.

Yet distribution of guidelines is not implementation (Reference Bero, Grilli and GrimshawBero et al, 1998; Reference ClarkClark, 2003). If the volumes are not simply to gather dust on shelves then their widespread distribution must be followed up by implementation strategies developed at local level and given systematic backing from within the structures of local health communities (Reference JankowskiJankowski, 2001). Such strategies need to work with professionals, service users and families across the primary/secondary care divide to foster and encourage the much that is good within local service delivery while at the same time developing services further and correcting what is bad. The NICE schizophrenia guidelines should complement and enhance service development already mapped out within documents such as the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) and the Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide (Department of Health, 2001). Schizophrenia is rightfully centre stage, and care and management for this patient group should be the benchmark by which a service both judges itself and is judged by others.

The implementation in routine service delivery of any health care interventions with a good evidence base is a major task; for a condition such as schizophrenia, where much evidence is poor or lacking altogether, it is harder still. Interventions that do have strong evidence of efficacy may not be available in routine practice (Reference Singh, Wright and BurnsSingh et al, 2003). The task of local implementation strategies will be to seek to increase the availability of interventions with a good evidence base while at the same time integrating these into the routine care, continuity and wider biopsychosocial approach that a condition such as schizophrenia demands. This is simple to say, but achieving it in practice will require substantial effort and resources. In some parts of the country, struggling with problems such as widespread consultant and other vacancies, rapid staff turnover and services permanently stretched beyond capacity, the prospects of implementation will seem remote. In other places, there is no realistic dialogue between providers, commissioners and service users, producing further obstacles. In some regions, such difficulties may appear insurmountable and achieving implementation a pious dream.

At the heart of the NICE guidelines, however, is the injunction to approach the management of schizophrenia in a spirit of hope and optimism; this article is intended to convey that this might equally apply to the task of implementation.

The schizophrenia guidelines

Schizophrenia was selected as the first condition for which national treatment and management guidelines would be published, and their development, including widespread consultation, took nearly 2 years. The Guideline Development Group included professionals from various disciplines, service users and carers. The guidelines contain evidence-based recommendations for pharmacological, psychological and service-level interventions embedded within a wider philosophy emphasising collaboration between service users, professionals and families, therapeutic optimism and a broad biopsychosocial approach across the different phases of the condition (Box 1). The limitations of the evidence base are reflected in the large number of ‘good practice points’ contained within the guidelines, which represent the consensus view of the Guideline Development Group on important aspects of the management of schizophrenia for which the evidence base from randomised controlled trials is inadequate or non-existent.

Box 1 The schizophrenia clinical guidelines

-

• Outline structure

-

• Principles of care across phases

-

• Initiation of treatment

-

• Treatment of the acute episode

-

• Promotion of recovery

-

• Audit measures

Specific interventions across phases include:

-

• working in partnership

-

• pharmacological interventions

-

• psychological interventions

-

• service-level interventions

The NICE guidelines were developed for England and Wales. They have subsequently been adopted by national agencies in Italy and Australia. Scotland has its own process of guideline development and produced guidelines on the psychosocial management of schizophrenia as long ago as 1998 (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1998). Scottish guidelines contain more extensive advice on implementation strategies than are currently contained in the NICE guidelines for England and Wales.

From dissemination to implementation

The cost of producing guidelines is likely to be substantially less than that of effectively implementing them (Reference Feder, Eccles and GrolFeder et al, 1999). The number of guidelines issued throughout the world in recent years for all areas of health care has risen dramatically – with over 1000 reported to have been issued in the USA (Reference LarsonLarson, 2003) – but the task of implementation often receives only cursory attention within the guidelines themselves.

Implementation strategies need to be considered at several different levels (Box 2). The decision to commission and produce guidelines is, at the very least, a tacit acknowledgement that standards of care are not uniform and that service structures and systems may vary widely. Individual professional practice also shows wide variation. Although guidelines are not a substitute for clinical judgement, professionals are expected to ‘take [them] fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement’ (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002). The aim of guidelines may therefore be to achieve more uniformity in the way that people with a certain condition are managed. At the same time, in a complex condition such as schizophrenia, it is neither possible nor sensible to be rigid. In its schizophrenia guidelines, NICE emphasises that the formation and maintenance of a therapeutic relationship is at times more important than any specific intervention. It also explicitly acknowledges that the guidelines are not intended to address particular challenging areas facing services, such as psychosis with comorbid substance misuse, but it does emphasise the importance of comprehensive assessment that covers these areas and wider issues, including risk.

Box 2 Guideline implementation: key issues

-

• Dissemination

-

• Ownership

-

• Barriers to change

-

• Sustainability

Nevertheless, evidence suggests that both in the UK and elsewhere the management of schizophrenia is often suboptimal (Reference Harrington, Lelliott and PatonHarrington et al, 2002a ,Reference Harrington, Lelliott and Paton b ). This may be a reflection in some cases of inadequate resource allocation, but it might also reflect the effects of stigma, discrimination and social exclusion often experienced by people with psychosis (Reference Meltzer, Singleton and LeeMeltzer et al, 2002) or poor management of the resources that are available. Finally, at the individual practitioner level, there may be deficiencies in knowledge or practice. Implementation strategies targeted at individual practitioners must therefore be part of a systematic approach that understands the theory underlying interventions aimed at behavioural change. This needs to be complemented by interventions aimed at the systems and structures of the organisations employing individual practitioners and the wider community in which they operate.

The emphasis on primary care within the title of the NICE guidelines illustrates another key point. Primary care is ideally placed to play a central role in ensuring effective implementation, given the easy availability of computerised systems, identifiable populations and the continuity of care available. Primary care has in recent years built up considerable expertise in managing and administering disease registers for chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes, and the experience gained from this should inform the development of practice-based severe mental illness registers. Examining the boundaries between primary and secondary care for this patient group and assessing the impact of their effect on care delivery are important implementation tasks.

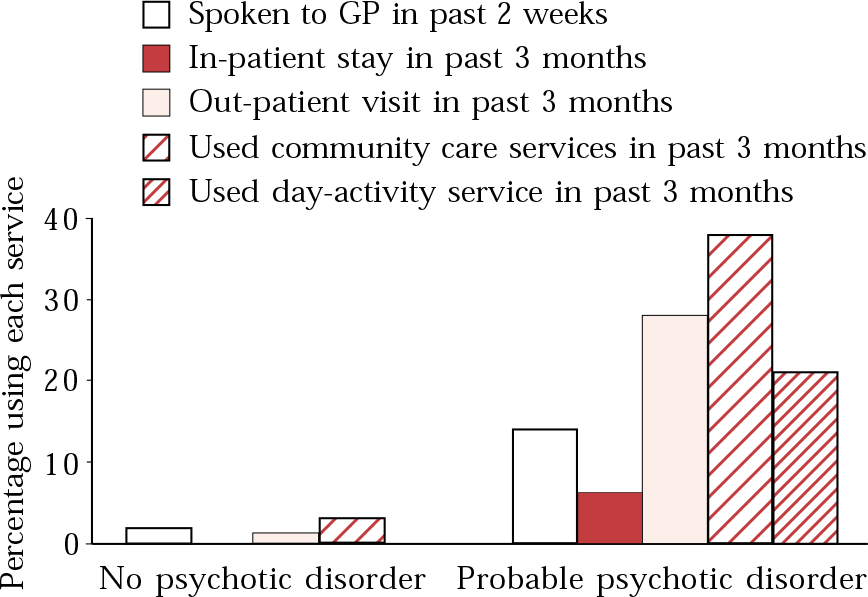

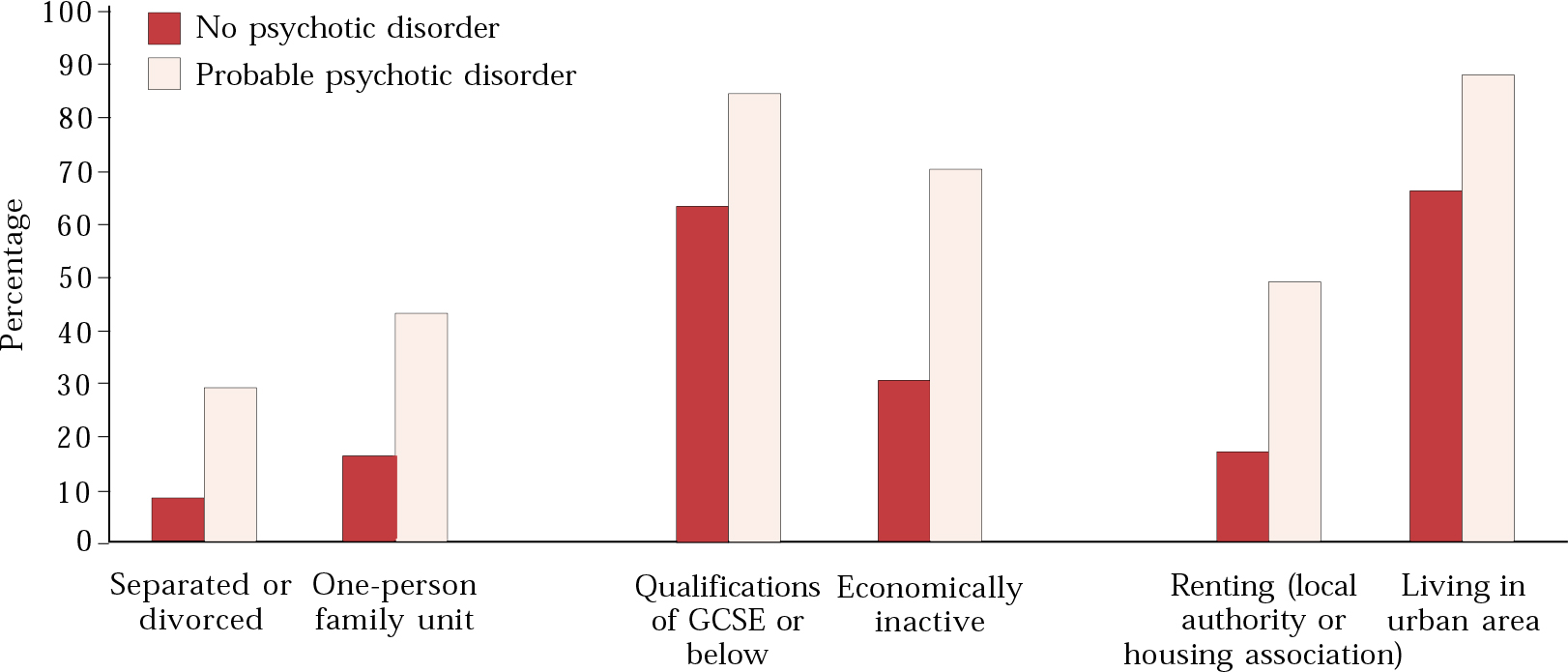

Data from the Office for National Statistics’ psychiatric morbidity survey, involving interviews with 8800 adults living in private households in 2000 (Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'BrienSingleton et al, 2001), suggest that the majority of people with psychosis are not in contact with secondary care services. They are more likely than the general population to be leading isolated lives and to be out of work (Figs 1 & 2). The prevalence of psychosis in the sample was estimated at 5 per 1000, and the same study suggested that the main treatment offered was pharmacological.

Fig. 1 Use of health care services for mental and emotional problems by people with and without probable psychotic disorder ( Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'Brien Singleton et al, 2001 ). Crown copyright, reproduced with permission.

Fig. 2 Characteristics of people with and without probable psychotic disorder in the year before interview ( Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'Brien Singleton et al, 2001 ). Crown copyright, reproduced with permission.

Implementation strategies

Individual practitioners

The behaviour of individual health care professionals is influenced by a wide range of factors. The ‘social influences’ model of behaviour change suggests that individual beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and psychological factors interact with peer-group influences, the culture and attitude of the employing organisation and wider social forces to shape behaviour in a particular clinical situation. Altering individual behaviour is therefore a complex task and should be approached as part of a wider strategy taking this fully into account. The patchy quality of the implementation literature means that there is much scope for further research on the optimal strategies. In addition, much of the literature is focused on primary care and is not explicitly related to mental health. The NICE schizophrenia guidelines are ambitious in scope, and implementing them is likely to be a much greater task than, for example, implementing typical primary care guidelines on simple procedures such as immunisation. A blend of approaches is likely to be required, but what is clear is that the simple dissemination of written material is likely to be ineffective (Reference Bero, Grilli and GrimshawBero et al, 1998; Reference Bannait, Sibbald and ThompsonBannait et al, 2003).

At the individual level a number of techniques are worth exploring. These are listed in Box 3 and examined in greater detail below.

Box 3 Implementation strategies: individuals and teams

-

• Academic detailing/educational outreach

-

• Interprofessional education, team-based learning

-

• Interactive workshops

-

• Audit and feedback

-

• Reminders

-

• Use of prompts

Academic detailing

Academic detailing, also called educational outreach, refers to an approach in which local ‘opinion leaders’ meet with other professionals to disseminate new ideas and shape practice. Literature reviews (Reference Thomson O'Brien, Oxman and DavisThomson O'Brien et al, 2003a ,Reference Thomson O'Brien, Oxman and Davis b ) reveal that the approach has been used for a wide range of clinical conditions, but it is not always clear what was involved and mixed results are reported. The schizophrenia guidelines provide an opportunity for local services to explore how such approaches might be employed. Relevant parts of the guidelines could be adapted for specific audiences and used as the subject of CPD meetings. The best evidence is in favour of interactive workshops rather than didactic lectures, and such sessions could foster important local networks involved in care delivery. This might be particularly useful in breaking down some of the barriers between primary and secondary care.

Interprofessional education

Although Reference Zwarenstein, Reeves and BarrZwarenstein et al(2003) found over 1000 studies looking at interprofessional education as opposed to learning on a uniprofessional basis, it was felt that none was methodologically rigorous enough for inclusion in their review of the subject. The approach, however, does have a face validity for the implementation of guidelines for a complex condition that requires effective multidisciplinary teamwork. In mental health, it would lend itself to incorporation with other techniques such as use of interactive workshops. A CD-ROM has been issued through NICE entitled Using and Understanding the NICE Guideline: A Training Session, which would lend itself to use in a small group session or individually (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003).

Interactive workshops

In contrast to the review of interprofessional education, a systematic review of continuing education meetings and workshops (Reference Thomson O'Brien, Freemantle and OxmanThomson O'Brien et al, 2003c ) suggested that some effect on practitioner behaviour could be achieved if the educational intervention included interaction. Didactic presentations alone did not appear to have any major impact in the seven studies reviewed. Again, this would lend support to an implementation strategy that included interactive workshop-style presentations involving key professional groups and service users (Boxes 4 & 5).

Box 4 Using the NICE guidelines algorithm to map local services and facilitate team-based learning

-

1 A case vignette is developed (e.g. presentation of first-episode psychosis in a young man)

-

2 A small group discussion (e.g. involving a team or part of a team within a locality) is held, using the algorithm

-

3 The group reflects on current practice, compared with guideline recommendations

-

4 The group identifies areas of strength and weakness

-

5 The group explores ways in which improvement could be achieved both using existing resources and with additional resources

-

6 The group feeds back into the wider local guideline implementation group

Box 5 Using guideline recommendations to develop partnership working: advance directives (NICE audit standards 7 and 8)

A top-down approach to implementation of advance directives is unlikely to instil a sense of ownership or to ensure sustainability. However, the bottom-up involvement of clinicians in group discussion might achieve this (Reference ThomasThomas, 2003).

Recommendations regarding advance directives offer an ideal opportunity to foster the development of collaborative working and ownership, using such questions as:

-

• What are advance directives?

-

• What does this recommendation mean?

-

• What would be the nature of the discussion with a service user to develop an advance directive?

-

• How can their use be tied in, for example, with work on relapse signatures and crisis and contingency planning?

-

• How can service users be involved in developing ideas regarding advance directives?

For further information on advance directives in APT see Reference Williams and RigbyWilliams & Rigby (2004)

Audit and feedback

Although clinical audit is a central component of clinical governance systems, its systematic development within the NHS is poor (Reference LelliottLelliott, 2003). Individual feedback and audit could potentially influence professional behaviour, although the evidence in this area is again weak (Reference Thomson O'Brien, Oxman and DavisThomson O'Brien et al, 2003d ). Within the NICE schizophrenia guidelines there is an appendix outlining key audit standards. Establishing whether these standards are met at a local level would greatly inform service delivery. To achieve this at secondary care level would require much better information technology systems than are currently available in most services: at present, most clinical audit projects are dependent on manual, prospective data collection. However, at an individual general practice level, with most practices having well-developed electronic records, the task of audit of at least some key measures is substantially easier (Box 7, on p. 409, outlines how practice-based electronic records can be used to construct a severe mental illness register and to audit key measures).

Box 7 Establishing a practice-based severe mental illness register in primary care: using a team-based educational intervention (NICE audit standards 6, 11, 12)

Getting started:

-

1 Identify target GP practices (e.g. those served by a locality sector service)

-

2 Offer a practice-based educational meeting about severe mental illness

-

3 Use this meeting as an opportunity to discuss:

-

• the biopsychosocial management of severe mental illness and the crucial role of primary care in its treatment

-

• the possibility of generating a practice-based register of people with severe mental illness

-

-

Aim to agree on action arising from the meeting and try to agree on the principle of follow-up meetings

If the practice agrees to set up a register:

-

1 Using the practice's computerised records, identify people taking antipsychotic medication (this will be overinclusive)

-

2 Identify people with diagnostic codings that suggest severe mental illness

-

3 Use the knowledge of the practice's GPs to supplement the data gathered

-

4 From the list generated, remove those who do not have severe mental illness

This list of names forms the basis of the register, and can be used in simple audits of, for example, level of contact with secondary services, levels of polypharmacy and standards of physical health care. With the agreement of the patient, the computerised record can be tagged with a specific ‘read code’

Reminders

Within electronic records it is a simple task to issue reminders regarding particular interventions or to adjust templates to do this. For example, in lithium monitoring a blood-test report form can be used to generate a reminder when the next test is required, or care programme approach systems can incorporate reminders of actions to be taken.

Use of prompts

Pharmaceutical companies have demonstrated substantial success in influencing practitioner behaviour. In addition to using combinations of the above approaches, they offer ‘prompts’ such as small gifts incorporating company logos and the sponsorship of large meetings. We are all familiar with their use of academic detailing, with representatives presenting research findings either to individual clinicians or to small groups, and with their recruitment of ‘opinion leaders’. Their tactic is collaborative and persuasive, rather than combative and critical. A more recent development is the recruitment and targeting of service users or consumers (Reference HealyHealy, 2002). The success of drug companies in achieving widespread changes, particularly in prescribing practice (e.g. in the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and atypical antipsychotics), calls for close study of their approaches. Perhaps we can learn from them and modify their methods for our own use. It should not go unnoticed that, to achieve their success, the pharmaceutical companies invest heavily in the materials that they produce, the studies they sponsor and the personal representatives they employ.

Implementation strategies

System approaches

The management of schizophrenia cuts across many organisational boundaries. If changes are to take place at an individual level, it is essential for there to be a commitment to implementation from the highest levels of the organisations concerned. At the same time, it is crucial that organisations borrow from the approach explicit in the NICE guidelines: improvements in care are more likely to occur with collaboration and involvement of people rather than by diktat and coercion. The major organisations that must commit to implementation are the commissioning bodies, via the primary care trusts, and the major provider organisations such as NHS trusts. Because much of the care of people with schizophrenia takes place within the remit of NHS secondary care trusts, it makes sense for these to take a lead role in establishing steering groups to examine the process of implementation. Such a group would need to work collaboratively with local commissioning bodies within the primary care trusts if and when resource implications were identified. A range of strategies are required, together with measurable outcomes to evaluate change (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2002).

However, implementation should not rely only on the receipt of extra resources from central government. The reality of the NHS is that trusts are going to continue to be expected to work largely with existing resources and to ensure that these resources are efficiently and appropriately targeted. The local delivery plans of primary care trusts will need to be informed largely by secondary care because the systems to gather routine data about this patient group are either not available or not utilised by commissioning bodies (Reference LelliottLelliott, 2003).

Establishing a steering group

A multidisciplinary steering group, including service-user representation, is a necessary complement to senior managerial commitment to implementation (Box 6). In some settings, clinicians themselves might have to set up such a group to focus the attention of senior management on schizophrenia services. A primary task for this group would be to evaluate the local scene from a clinical and service-user perspective, with a view to informing the managerial and commissioning aspects of service development (e.g. see Reference Singh, Wright and BurnsSingh et al, 2003; Reference Snowden and MarriottSnowden & Marriott, 2003). This is no small task, although the mapping and evaluation of current service provision (Box 4) would necessarily overlap with educational interventions at all clinical and managerial levels. The aim would be for an inductive process to develop, whereby local evaluation spreads awareness of the guidelines and increases a sense of ownership of them at an individual practitioner level. The ultimate sustainability of the guidelines will depend on many things, not least of which will be the development of this sense of ownership. Ownership needs to be felt at all levels, ranging from the senior management of NHS and primary care trusts to individual service users, carers and care coordinators. Senior clinicians, as opinion leaders, are likely to have a vital role in attempting to promulgate the content and philosophy of the guidelines across the disparate organisations involved.

Box 6 Using system-based implementation strategies

System-based approaches are, by definition, removed from the clinical front line. Nevertheless, they must be informed by the realities of clinical practice and attempt to involve wide and dispersed groups collaboratively. Establish a local steering group to oversee the strategy:

-

• include service-user representatives

-

• recruit the support of senior management in provider organisations

-

• recruit the support of commissioning bodies

-

• recruit and involve clinical opinion leaders

-

• survey the local situation: strengths, weaknesses, gaps

-

• establish a strategy/action plan with measurable outcomes

-

• influence the local training agenda

-

• establish severe mental illness registers in primary care

-

• establish effective systems for information management, including meaningful outcome measures

-

• establish service structures that meet the guidelines and monitor that these are appropriately targeted,

-

• effectively deployed and properly resourced

-

• review, audit and revise the action plan against the set outcome measures

Using clinical information management systems

Reference LelliottLelliott (2003) has described the potential benefits of good information management systems that allow routinely collected data to be used for secondary purposes such as education, audit, supervision, service planning and service evaluation. Unfortunately, such systems within the NHS have thus far been poorly developed and implemented. Nevertheless, even the current systems have the potential for development. This could include use of care programme approach data or, as in the following example, of data routinely held within primary care at a practice level.

Severe mental illness registers in primary care

The NICE guidelines support the development of primary care registers of severe mental illness, and the proposed new general practitioner contract includes payments for the establishment of such registers. Although this is part of a wider agenda for the development of effective health information systems, approaching this from a primary care (practice-based) level has a number of advantages. First, the problem takes on manageable proportions. Second, addressing it requires clinicians to cooperate across the primary/secondary divide in a way that lends itself to sustainable change. Third, and importantly, electronic records within primary care are at a much greater level of sophistication than are those within most secondary services at present, allowing easy construction of lists of patients with a particular condition using simple computer templates.

This official guidance therefore potentially opens the doors to collaborative involvement of primary care at both individual practitioner and commissioning levels (Box 7).

The care programme approach

The secondary care equivalent of primary care severe mental illness registers is the care programme approach data-set. The quality and nature of data collected and factors such as case mix and lack of agreed definitions complicate interpretation of this and it remains the case that many mental health services are unable to quantify who they see, what they do and what the outcomes are (Reference LelliottLelliott, 2003). Repeated organisational change and the dispersed nature of care has undermined attempts to get to grips with the major issues, although there are continued efforts to establish minimum data-sets and routine outcome measures with proper clinical meaning (Reference Charlwood, Mason and GoldacreCharlwood et al, 1999).

If outcome data were available routinely then again the data could feed directly into education, audit and reflective practice as well as into the informed planning of service developments at a more strategic level. Targets for quality improvement would be easily generated and monitored and the availability, uptake and effectiveness of specific evidence-based interventions advocated within the guidelines could be easily monitored.

Training agenda

The training agenda of NHS and primary care trusts should be shaped by the guidelines, which reflect a commitment to a biopsychosocial approach to schizophrenia. The evidence-based interventions described and supported cannot be seen as separate from the fundamental issues of attempting to develop and maintain a collaborative relationship retaining an awareness of the wider psychosocial context to the disorder and its management. A tiered approach, modelled on approaches that have been suggested for other psychiatric conditions such as depression (Reference Whitfield and WilliamsWhitfield & Williams, 2003), offers one way of developing and sustaining staff training (Box 8).

Box 8 A tiered approach to training for psychosocial interventions (NICE audit standards 1, 2, 9, 10)

-

• Basic introductory training for all staff working with people with severe mental illnesses

-

• Training with teams to foster the psychosocial intervention approach

-

• Training of trainers to introduce the principles (e.g. of family working) throughout a locality

-

• Training of individual workers in more advanced or specialised skills (e.g. at degree level)

-

• Ensuring that the working environment (caseloads, management support, supervision) facilitates the use of psychosocial interventions in routine practice

-

• Complementing the psychosocial intervention strategy with a vocational rehabilitation strategy

(After Reference Whitfield and WilliamsWhitfield & Williams, 2003)

Policy and procedures

The NICE guidelines stress the importance of revising local clinical guidelines in the light of their recommendations. Of the areas covered by the NICE guidelines, an obvious place to begin would be with rapid tranquillisation protocols. This is an area of practice that is potentially dangerous as well as distressing. The NICE guidelines provide a clear framework for development of a policy and its implementation. However, as with any guidance, implementation in clinical practice requires more than production of a written policy.

Service structures

Specific service structures such as assertive community treatment for certain groups are strongly supported by the NICE guidelines. This dovetails with governmental priorities within the NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000) and the specific Department of Health policy documents (Department of Health, 2001). This national strategic impetus to service development has led to the establishment of assertive community treatment teams in most parts of England. It is a key implementation task to ensure that these teams remain firmly focused on the correct target group, i.e. people who are high users of services or who are difficult to engage. The NICE guidelines suggest administrative criteria for allocation of cases to assertive community treatment teams, which would be helpful in avoiding boundary disputes between these teams and other parts of the service and might also be useful in ensuring that each team has an adequate caseload (10–15 per care coordinator equivalent). Assertive community treatment is costly and its cost-effectiveness will depend on the targeting of appropriate patient groups as well as ensuring that caseloads are large enough to justify the service's separate existence from the rehabilitation and recovery service offered by community mental health teams. Community mental health teams are still seen within national guidance as central to care delivery and it is important that these teams, ‘the core round which other newer services are developed’ (Department of Health, 2001, 2002), receive adequate resourcing and managerial support.

Other service structures supported include day hospitals (which have a strong evidence base of efficacy) and early-intervention services, although the evidence base for the latter innovation is currently lacking. The NICE schizophrenia guidelines suggest that, although early intervention has some face validity, its introduction should be evaluated against alternative approaches such as augmentation of existing community mental health teams.

Role of employment and wider social issues

The NICE guidelines and other work (e.g. Reference Mountain, Carman and IllotMountain et al, 2001) emphasise the importance of patients’ daytime activity in general and work in particular within the overall comprehensive assessment and management of schizophrenia. Implementing guidelines in this area begins to involve an even wider constituency than the other parts of the recommendations. Supported employment programmes, which aim to place people in the mainstream labour force without prolonged ‘training’, have some evidence in their favour but are by no means suitable for everyone. Developing supported employment as part of a spectrum of opportunities for individuals requires a vocational rehabilitation strategy supported managerially by relevant agencies and implemented through professional groups such as occupational therapists (College of Occupational Therapists, 1999). The vocational rehabilitation strategy should be seen as an important component of the wider local implementation strategy for the guidelines, complementary to other strategies such as that for psychosocial intervention (Box 9).

Box 9 Policies, procedures and service structures (NICE audit standards 3, 4, 5, 13)

-

• Rapid tranquillisation

-

• Criteria for assertive community treatment/assertive outreach

-

• Involvement of individuals and their carers/advocates in care planning

-

• Provision of second opinions if required

-

• Ensuring that continuity of care across phases is maintained within any new service structures

-

• Ensuring adequate resourcing of core service structures (e.g. rehabilitation and recovery community mental health teams)

-

• Ensuring provision of culturally appropriate services and information

Challenging the stigma and discrimination that people face once they have acquired a diagnosis of schizophrenia is part of a much wider agenda that implementation strategies will need to address. Vocational rehabilitation, requiring links with other non-mental health agencies, offers opportunity in this direction.

Conclusions

The NICE guidelines offer many challenges to professionals and commissioners to improve the lot of people diagnosed with schizophrenia. The guidelines are clinically focused and emphasise partnership working and a broad biopsychosocial approach to this condition. The guidelines have received a generally favourable response and other countries, including Italy and Australia, have shown an interest in them. However, successful implementation will require more than this. Local health communities will need to adopt a broad approach, working collaboratively with professionals, service users and their families. The task in some parts of the country may be simply too difficult and the agenda too ambitious. In other areas, perhaps less hamstrung by chronic resource shortages and other structural difficulties, local senior clinicians, with management support, are in a crucial position to take this agenda forward.

MCQs

-

1 The NICE schizophrenia guidelines:

-

a must be followed in all suspected cases of schizophrenia

-

b largely comprise recommendations based on strong evidence from randomised control trials

-

c emphasise the importance of a collaborative relationship between services and service users

-

d strongly support the concept of assertive community treatment

-

e strongly support the immediate introduction of separate early intervention services.

-

-

2 The following are likely to be effective ways of achieving implementation of the guidelines:

-

a distribution of the guidelines in written form

-

b team-based interactive workshops led by senior clinicians

-

c the issuing of local guidelines by trusts’ clinical governance committees

-

d workshops involving both primary and secondary care

-

e use of severe mental illness registers in primary care.

-

-

3 Severe mental illness registers in primary care:

-

a receive support within the NICE guidelines

-

b payments related to these are included within the new general practitioner contract

-

c facilitate audit of key implementation tasks

-

d are likely to require complex, expensive new information technology systems

-

e offer opportunities for professional collaboration at a clinical level between primary and secondary care.

-

-

4 The following represent important strategic tasks for implementation:

-

a establishing ownership of the guidelines at a senior managerial level in primary care and mental health trusts

-

b the establishment of a guideline-implementation steering group

-

c ensuring wide dissemination of the guidelines in written form

-

d involving teams in local implementation

-

e establishing training strategies for key areas.

-

-

5 Advance directives:

-

a are not mentioned in the NICE schizophrenia guidelines

-

b can be implemented through use of team-based training

-

c can be used as a means of fostering collaborative working

-

d may be linked with contingency planning

-

e may be linked with work on relapse signatures.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.