It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of mental health to the social, financial and physical well-being of contemporary society.

Readers of this journal will be well aware of the adverse impact of mental illness, but the statistics bear repeating. About 70% of people know someone who has been diagnosed with a mental health problem, and about one in four people have been so diagnosed themselves (Reference Braunholtz, Davidson and KingBraunholtz et al, 2005). At least a third of work absences and a half of incapacity benefit claims are caused by mental health problems. The cost of depression and anxiety in the UK has been estimated at £17 billion, equivalent to 1.5% of gross domestic product (Reference LayardLayard, 2006). Consumption of antidepressants has trebled in a decade, with an estimated 8.7% of the population in Scotland taking antidepressants in 2005–2006; similar rates have been reported in other Western countries (Information Services Division Scotland, 2007). The UK spends 12% of its health budget on mental health, the second highest proportion in the European Union (European Commission, 2005).

Public interest in mental health is therefore appropriate and perhaps unsurprising. But this interest in mental health does not equate to an interest in psychiatry. In fact, this article argues that few people care about the profession or practice of psychiatry apart from psychiatrists themselves.

To be concerned about public indifference to our work is not to indulge in professional navel-gazing. Without public support for a clinical perspective on mental health, our profession risks a marginalised future. Reference EisenbergEisenberg (2000) was right to assert that ‘neither mindlessness nor brainlessness can be tolerated in medicine’: but should we not be equally intolerant of the ‘pointlessness’ of a marginalised profession?

The following personal view rejects Adam Smith's assertion that the professions are invariably a ‘conspiracy against the public’, and embraces instead a vision for psychiatry that would allow it to take a respected place in national life. ‘Public psychiatry’ constituted in this way would not only serve a common good, but also enable the profession to acquire and maintain public respect.

I will begin with the ‘problem of pointlessness’– the dismal status of psychiatry, despite immense public and political interest in mental health issues.

The public status of psychiatry

Many psychiatrists would feel a stirring of pride and recognition as we read the comments of Professor Richard Layard about the importance of mental health services:

‘It is a complete scandal that we spend so little on mental health. Mental illness causes half of all the measured disability in our society and, even if you add in premature death, mental illness accounts for a quarter of the total impact of disease. Yet only 12% of the NHS budget goes on it and 5% of the Medical Research Council budget. Roughly 25% of us experience serious mental illness during our lives, and about 15% experience major depression …

If we really wanted to attack unhappiness, we would totally change all this, and make psychiatry a central, high-prestige part of the NHS' (Reference LayardLayard, 2003).

By contrast, informed criticism of the following kind is likely to raise the hackles of psychiatrists everywhere:

‘Psychiatric medicine … has few achievements to boast about. Indeed at times psychiatrists have advocated treatments that can fairly be described as cruel and barbaric … Today, in the case of the most severe mental illnesses at least, the outcomes obtained are little better than those obtained at the end of the 19th century’ (Reference BentallBentall, 2004).

These views exemplify a dichotomy in the scholarly interpretation of psychiatry's position in society. This split has two opposing visions. On the one hand, there is a ‘heroic’ version of the profession, which emphasises the progress of a humane science to the benefit of patients. This view is largely presented by psychiatrists or clinicians. The alternative is a more sceptical ‘social history’, which places particular emphasis on the non-clinical nature of many mental health problems, and the social control and professional self-interest exerted by psychiatrists (Reference BerksBerks, 2005).

How is a member of the public to make sense of these two perspectives? Unfortunately, popular understanding is hindered by poor ‘mental health literacy’: we know that many members of the public cannot correctly recognise mental disorders, and do not understand the meanings of psychiatric terms. Much of the mental health information most readily available to the public is misleading, and such misinformation and lack of knowledge hinder appropriate help-seeking (Reference JormJorm, 2000). The situation is complicated by the fact that ‘the public’ is not a homogeneous entity, but instead a variety of different ‘publics’.

The ignorance and misinformation experienced at a population level might partly be attributable to the predominant role the media play in disseminating information about mental health. Peoples' primary source of information about mental illness is television news, with national newspapers coming second; information from health professionals comes fourth, after word of mouth (Reference Braunholtz, Davidson and KingBraunholtz et al, 2005).

Given the bias evident in media reporting of mental illness, it is not surprising that psychiatry risks being misrepresented or misunderstood. These problems are likely to be exacerbated by stigma, which means that many people are reluctant to speak about their personal experiences. There is little media interest in people recovering from illness or quietly coping with its consequences.

But we should be wary of scapegoating the media for mental health illiteracy. Uncomfortably for psychiatry, many people with close personal experience of psychiatrists hold markedly critical views. In an interesting qualitative study, the Highland Users Group in Scotland identified a number of psychiatric stereotypes described by service users (Box 1).

Box 1 ‘Psychiatrists’

The Nutty Professor

An eccentric, absent-minded, dishevelled east-European professor (probably wearing a white coat) whom people see while lying on a couch.

The Aloof Interrogator

An imposing intellectual who is usually male and wears a suit. He comes across as arrogant and remote, and sits in a big chair. He delves into people's minds and lives and changes them as a result of this. He is possibly closed-minded and pompous, maybe slightly ‘scary’, but is sometimes very clever and perceptive.

The Powerful Man

A man who has the power to lock up the criminally insane and any other person with a mental illness. His remit seems to be simply to ‘put people away.’ Another type are the ‘brain washers’ and ‘clinical dictators’ who turn people into zombies with medication.

The Middle-Class Conformist

People from a middle-class background, who are university educated and part of a system that respects conformity and authority. They would usually tend to side with either the police or employers, and agree with the views of family members rather than those of the patient.

The Analyst

People who pry into and analyse the dreams and childhood of other people. They are ‘mind benders’ and are sometimes people of whom patients would be wary. They are people who are likely to suggest that what patients are thinking is wrong.

The Mentally Ill Person

People who are themselves damaged and have chosen to become psychiatrists because they have never sorted out their own problems.

Their report recognised that ‘these images are often wildly inaccurate … but that they probably do hold some grains of truth. They have probably been created by a general antipathy towards psychiatry in the general public, and also as a result of the relatively recent history of abuse in mental health services’ (Highland Users Group, 2004).

Such views are often shared not just by the general public and service users, but by potential future psychiatrists. The following statements were made by medical students at Glasgow University after completing their 4th-year attachments in psychiatry:

‘ I chose medicine because I wanted to make people better, not hang around all day like a glorified social worker’; ‘

Psychiatry requires patience, perseverance and a degree of faith in therapies which are speculative or tentative, to treat conditions which are poorly understood, for which no satisfactory explanation can be given, and where conflicting or evolving classification systems make the wider picture difficult to view. I would rather be on my feet getting my hands dirty!'

Similar results have been reported elsewhere in the UK, the USA and Australia, where psychiatry was often regarded as the least attractive career option in the field of medicine. For example, psychiatry was rated the lowest of all specialties for job satisfaction and enjoyable work, for the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments, for the intellectual challenge and scientific foundation of the discipline and for the prestige of the profession (Reference Rajagopal, Rehill and GodfreyRajagopal et al, 2004). There is a UK-wide shortage of consultant psychiatrists in general psychiatry and most psychiatric specialties (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004).

Even where psychiatry is a designated ‘clinical priority’, investment in mental health services has lagged behind other medical specialties. For example, mental health is one of three national priority areas for NHS Scotland, but between 2000 and 2003, additional funding allocated to mental health services fell from 9% to 2.25%. Over the same period, spending on acute services showed annual increases of between 6.5% and 10.5%.

In summary, it has long been recognised that the general public may have poor mental health literacy. The hope that personal or professional engagement with psychiatric issues might lead to more enlightened views does not seem to be borne out in practice. Unfortunately, it seems that psychiatrists may be stereotyped by service users, dismissed by medical students, overlooked by policy makers and trenchantly criticised by academics. How should the profession respond?

Psychiatry's responsibility: is the public right to be critical?

Psychiatry's response needs to consider each of the criticisms made of the profession on its own merits. Contemporary practice is only defensible if clinicians and the public can see that care is responsive to patient needs, free from adverse biases and untarnished by stigma.

Quality care

Many patients who become active in service user organisations have been motivated to do so because of their damaging experience of mental health services. Reports of such negative experience often include psychiatrists failing to listen carefully to patients, misdiagnosis, prolonged admission without therapeutic advantage, unnecessary use of compulsion or the inappropriate use of medicines to ‘manage’ social and personal problems.

Many such stories are heartbreaking. However infrequent or atypical such bad practice may be, such situations have a devastating impact on public perception. Psychiatry has a moral responsibility to ensure that it actively identifies and manages all poorly performing doctors and untherapeutic systems of care. Acting to protect our professional reputation should be beneficial to patients, as well as in our enlightened self-interest.

Free from bias

Psychiatry needs to be aware of its potential for organisational bias. One of the most damaging criticisms made against contemporary psychiatry is that it is overdependent on a clinical model of care that has been hijacked by the pharmaceutical industry. This charge is potent because it carries considerable truth. As stated in a BMJ editorial:

‘Doctors and drug companies must work together, but doctors do not need to be banqueted, transported in luxury, put up in the best hotels, and educated by drug companies. The result is bias in the decisions made about patient care’ (Reference Abbasi and SmithAbbasi & Smith, 2003).

Psychiatrists need to support close working links with pharmaceutical companies in order to promote the continuing development of effective drugs. But doctors' fiduciary relationship with their patients – one characterised by good faith, loyalty and trust – is often in direct conflict with the profit-seeking motivation of drug companies. Many doctors underestimate the extent of this conflict, and this may represent a professional ‘blind spot’ in their relationship with patients (Reference BlumenthalBlumenthal, 2004).

Psychiatry needs also to ensure that it is free from racism (Reference McKenzie and BhuiMcKenzie & Bhui, 2007) and other forms of discrimination.

Non-stigmatising

Stigma related to mental healthcare accounted for almost a quarter of stigma experiences reported by mental health service users in Germany (Reference Schulze and AngermeyerSchulze & Angermeyer, 2003) and in Scotland (Reference McArthur and DunionMcArthur & Dunion, 2007).

In a review of 22 studies comparing attitudes of mental health professionals and the general public towards mental illness (Reference SchulzeSchulze, 2007), only 6 studies found that professionals were less stigmatising than the public, with 9 showing no difference and 7 suggesting that professionals had more negative attitudes. For example, Swiss mental health professionals expressed more negative and less positive stereotypes regarding people with mental illness than did the general population (Reference Lauber, Nordt and BraunschweigLauber et al, 2006). There is evidence that such stereotypes are acquired during medical education. Even when special efforts are made to provide a ‘destigmatising’ clinical experience for medical students, any positive shift in attitudes soon disappears when they begin work as junior doctors (Reference Wilkinson, Toone and GreerWilkinson et al, 1983).

One possible explanation for such negative attitudes may be that psychiatrists have a ‘distorted’ personal experience of mental illness. Psychiatrists usually see people when they are at their most ill, and have case-loads disproportionately composed of people with chronic problems. Daily clinical practice therefore tends to be biased towards severe disorder and non-recovery, and this experiential bias may influence attitudes (Reference SchulzeSchulze, 2007). External pressure from government to minimise perceived risk from people with mental illness may militate against appropriate therapeutic engagement with patients (Reference EastmanEastman, 2006) and thereby contribute to iatrogenic stigma.

Psychiatrists may also be responsible for more subtle forms of stereotyping. For example, a study in the USA found that although community mental health professionals viewed families of mental health patients as ‘supportive caregivers’, they also characterised these families as ‘unsupportive agitators’, ‘in pain’ and ‘uninformed’. They did not view them as equal partners with community teams, and seemed to split them into ‘good families’ and ‘bad families’ (Reference RiebschlegerRiebschleger, 2001).

Although psychiatrists (thankfully) showed reasonable diagnostic skills when interpreting case studies in vignettes, one in four considered the individual in the ‘non-case’ vignette to have a mental illness (Reference Nordt, Rossler and LauberNordt et al, 2006). The communication skills of psychiatrists have been criticised in a number of studies (reviewed in Reference SchulzeSchulze, 2007).

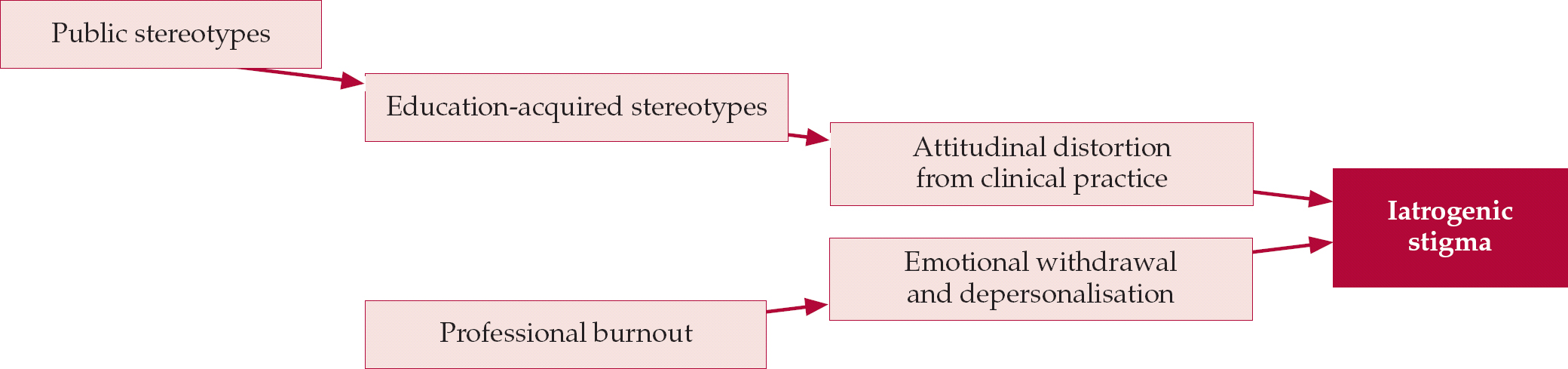

Reference SchulzeSchulze (2006) proposes one possible model for the psychiatric contribution to the stigma of mental illness (Fig. 1). She argues that medical students begin their training with the same stereotypes of mental illness as the general public. ‘Education-acquired’ stereotypes are then superimposed on these attitudes, followed by the distorted view of mental illness engendered by clinical practice in secondary care.

Fig. 1 Factors contributing to iatrogenic stigma (after B. Schulze, personal communication, 2007; with permission).

Inadequate funding for mental health services and excessive case-loads contribute to professional burnout, and the emotional withdrawal and depersonalisation associated with that makes us less accessible to our patients and less able to consider them holistically.

In summary, psychiatrists may be partly responsible for some of the stigma and poor care experiences reported by service users. Psychiatrists, of course, have to work in the same claustrophobic and sometimes threateningly ‘anti-therapeutic’ (Reference HolmesHolmes, 2002) in-patient environments used by their patients. A lack of resources is felt by service providers and users alike.

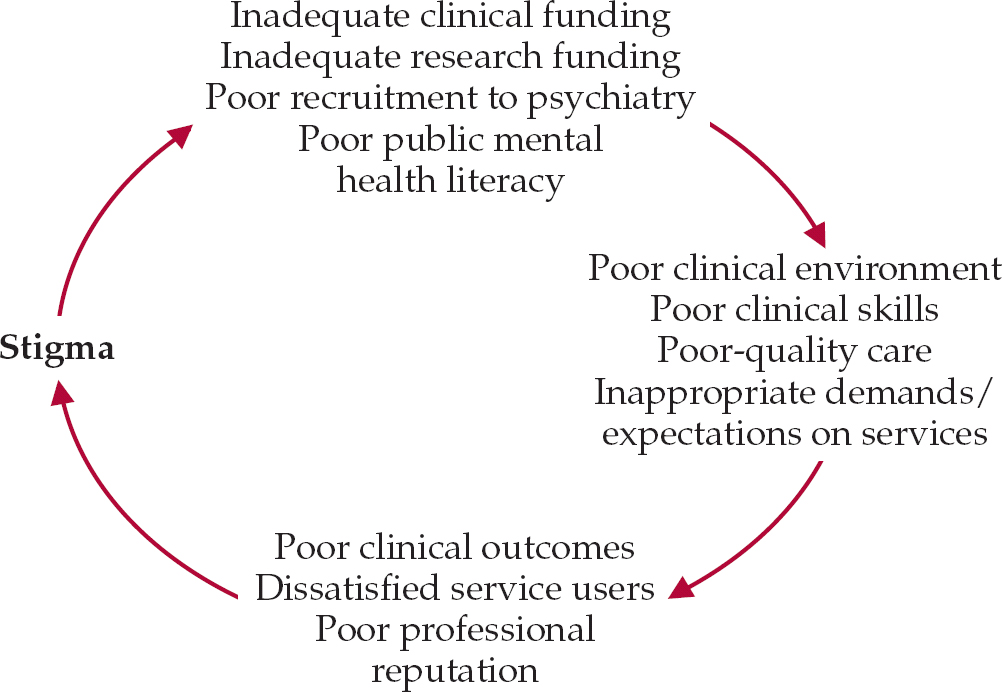

It is possible to envisage these factors combining to produce a negative cycle, whereby inadequate funding and poor recruitment lead to inadequate therapeutic resources and consequently to poor outcomes (Fig. 2). Such poor outcomes are unlikely to encourage further investment in services.

Fig. 2 A self-sustaining negative cycle of mental healthcare.

Public education and its problems

Stigma is a critical step in this loop, and the Royal College of Psychiatrists rightly emphasises the importance of programmes of public education and stigma reduction. However, the prospect of psychiatrists persuasively presenting ‘the facts’ to the public would depend on their audience being prepared to trust them (Reference Pilgrim and RogersPilgrim & Rogers, 2005). Such an assumption cannot be made: in fact, there is considerable resistance to such intervention.

Efforts by psychiatrists to ‘educate’ the public have been criticised for seeking to implement a ‘professional project’ that meets professional, not public needs. Psychiatry has been criticised for:

-

• trying to act as ‘social engineer’ with the aim of persuading the public to accept a psychiatric concept of mental health problems – even though closing the gap between lay and professional views of mental health problems may not be valuable to patients

-

• seeking to promote the use of mental health services, in part by presenting a misleadingly positive view of the quality of care and expertise available to patients

-

• reinforcing the view of the ‘needy patient’ by claiming that service users are primarily in need of professional help

-

• paying insufficient attention to the role of psychiatry in ‘social control’

-

• inappropriately using a normalisation model (e.g. ‘mental illness is an illness like any other’), which may be both inappropriate and ineffective

-

• having an attitudinal blind spot, in that it focuses on everybody's attitudes to mental illness bar those of psychiatrists themselves.

(This list was informed by my reading of Reference Read, Haslam and SayceRead et al (2006) and Reference SchulzeSchulze (2006).)

Psychiatry needs to deal with these plausible criticisms rather than claiming a professional right to educate the general public. This requires opening a dialogue with service users, many of whom are angry about their experience of the mental health system. Many psychiatrists are wary of encountering such anger, but remaining aloof or being perceived to be ‘not listening’ is likely to aggravate the problem. As one service user said:

‘I think the people who started up the service user movement were very angry and that gave us a lot of motivation to do something. I think that anger helped us to get through a time when we had to fight to be listened to. Then there was a critical mass reached when there were so many of us they had to listen’ (Reference Wallcraft, Read and SweeneyWallcraft et al, 2003).

Even in a neutral environment, psychiatrists may not be the best people to promote their own agenda. In my view, many psychiatrists are reluctant to engage with the public because of realistic anxieties of being ‘savaged’ (damagingly misrepresented) by the media or angry activist users, of contributing to a trivialisation of mental illness, or of unleashing an avalanche of pent-up demand. It's often easier to leave it to someone else.

Conceptualising ‘public psychiatry’

Thus, psychiatry is not as understood or respected as the profession would like it to be. This is in part a professional failure to communicate a psychiatric perspective: but there are good reasons for the public to be wary of such communication. Unfortunately, much of the middle ground in the engagement between psychiatrists and the public has been abandoned, leaving the field to strident activists and a small cohort of weary professional spokespersons.

This problem now faced by psychiatry is analogous to that confronted by academic sociology in the USA, where Burawoy (2004a) argues that ‘laments by intellectuals about their lack of public visibility have been replaced by a full-scale retreat from public life’.

Reference BurawoyBurawoy (2005) proposed a ‘division of labour’ in sociology that might inform a response to psychiatry's predicament. Although there are important differences between academic sociology in the USA and psychiatry in the UK, there are none the less instructive parallels between our situations (M. Burawoy, personal communication, 2006).

Loosely following Burawoy (2004b), ‘psychiatric work’ might be allocated to one of four interdependent domains (Fig. 3). The domains of professional, clinical and academic psychiatry are conventionally defined and probably uncontroversial. The significant shift in this model is to consider public psychiatry – the profession's ‘conversation with society’ – as a fundamental part of professional life, rather than as an offshoot or distraction from other activities.

Fig. 3 The four interdependent domains of psychiatry.

Public psychiatry seeks to enrich public discourse about moral and political issues relating to mental health by engaging in an informed way, supported by the best-quality psychiatric practice and research. Considered in this way, a discursive and open public psychiatry is quite distinct from one-way dissemination models of ‘public education’ or ‘public relations’.

Public psychiatry is emphatically not ‘media psychiatry’, especially where this panders to popular stereotypes, or becomes co-opted as a branch of the entertainment industry. Public psychiatry should be confident enough to be open about current dilemmas and past mistakes (what Peter Reference ByrneByrne (2000) refreshingly refers to as ‘dumb ideas in psychiatry’).

It makes sense that psychiatry should seek out this kind of productive discourse, since it is one of the clinical specialties most dependent on effective empathy, communication and creative engagement with patients. It is worth noting that the high prevalence of mental health problems means that a significant proportion of psychiatrists have been users, as well as providers, of mental health services.

Public psychiatry encompasses activities already undertaken by psychiatrists and coordinated by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, such as parliamentary liaison, public relations and media work, public education, anti-stigma programmes, partnership with the voluntary sector and service users and carers, and contributions to policy-making and legislation. All of these strands of activity are interdependent, and effective interventions in one area strengthen other aspects of public psychiatry. Partnership working is also more likely to earn respect from the public, and provide an opportunity for psychiatrists to learn from others while sharing their own perspective.

For example, the Scottish Division of the College was one of the founder members of ‘see me’, the Scottish anti-stigma campaign involving an alliance of five mental health charities (www.seemescotland.org.uk). Funding for the campaign was achieved after lobbying of Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) by the College in collaboration with service users and the voluntary sector. The success of this joint working led to the formation of a new Cross-Party Group on Mental Health in the Scottish Parliament. The group membership includes a broad representation of service users, carers, professional bodies and voluntary agencies as well as politicians; a psychiatrist is Secretary. Joint initiatives continue. For example, the Scottish Division and Scotland's biggest mental health charity – the Scottish Association for Mental Health – jointly hosted a 1-day meeting with staff, planners and services users aimed at providing ‘an opportunity to listen, participate and contribute to shaping the ideal acute mental health environment for people in hospital’ (www.samh.org.uk/frontend/index.cfm?page=339).

The ‘see me’ campaign has been associated with a reduction in the public perception of dangerousness and mental illness. For example, the proportion of people in Scotland agreeing with the statement ‘people with mental health problems are often dangerous’ fell from 32% in 2002 to 15% in 2004 and to 16% in 2006 (Reference Braunholtz, Davidson and MyantBraunholtz et al, 2007). Attitudes towards dan gerousness have become less tolerant in England over the same period (TNS, 2007), which may reflect the passage of a Mental Health Bill (Department of Health, 2006) for England and Wales with a strong emphasis on public safety and risk. Communicating the anti-stigma message of ‘see me’ through liaison with the Scottish Parliament helps to maintain appropriate attitudes among MSPs themselves. For example, when MSP John Swinney made stigmatising remarks about mentally ill patients being ‘two tablets away from flipping’, a motion ‘condemning and dissociating’ the Parliament from his remarks was signed by 54 (out of 129) MSPs within 2 hours (BBC News Scotland, 2003).

Conclusions

Public psychiatry describes a process of constructive, respectful engagement with society about mental health issues. This article argues that such discourse is a prerequisite not only for the delivery of quality psychiatric care, but also for psychiatry itself to acquire and maintain respect and clinical effectiveness.

A more engaged and less defensive profession would be able to respond to appropriate critiques of psychiatric practice. This is especially important to avoid the distortion of practice by stigma, racial or other forms of discrimination and the inappropriate influence of drug companies.

‘Mindful’ and ‘brainy’ psychiatry both have their place – but each requires a public and social context to be relevant and effective. Public psychiatry provides this context, and merits better recognition by the profession.

MCQs

-

1 Psychiatrists:

-

a are generally held in high esteem by the public

-

b are the most trenchant critics of their own practice

-

c actively seek dialogue with the public about mental health issues

-

d are wary of being misrepresented by the media

-

e have successfully presented their professional perspective to the public.

-

-

2 Critics of psychiatry argue that psychiatrists:

-

a present an unnecessarily negative picture of psychiatric interventions

-

b should have a greater role in enforcing normative social behaviour

-

c need to work more closely with the pharmaceutical industry

-

d receive insufficient remuneration compared with other doctors

-

e prefer to focus on anyone else's attitudes to mental illness bar their own.

-

-

3 The four proposed ‘domains’ of professional psychiatry include:

-

a telly psychiatry

-

b public psychiatry

-

c telepsychiatry

-

d slow psychiatry

-

e private psychiatry.

-

-

4 Psychiatrists' practice might unwittingly be influenced by:

-

a marketing gimmicks such as pharma-sponsored pens and adhesive notes

-

b a pervasive sense of optimism and hope in clinical settings

-

c the positive attitudes towards mental illness expressed by other doctors

-

d ample time for reflection and clinical discussion

-

e public recognition that many psychiatrists are service users too.

-

-

5 Which of the following is not a psychiatric stereotype?

-

a the aloof interrogator

-

b the nutty professor

-

c the mentally ill person

-

d the middle class conformist

-

e the therapist who listens and understands.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | F | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.