Obesity is a serious public health problem and a particular challenge in people with mental health disorders (Reference Devlin, Yanouski and WilsonDevlin 2000). Bariatrics is the branch of medicine that offers treatment of obesity, and bariatric surgery is an increasingly common intervention for morbid obesity. It is typically requested by the primary care team. Before an individual is considered for surgery, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) expects the patient to have engaged with a multicomponent programme of lifestyle change that has been individually tailored by a competent healthcare professional (National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care 2006). This should have incorporated a behavioural intervention to increase levels of physical activity and improve eating behaviour and quality of diet. In many cases, drug treatment with the lipase inhibitor orlistat will have been tried, although failure to respond to drug treatment is not a requirement for surgery. NICE has recommended that surgery be considered for all those with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2 who have failed to respond to other interventions and for those with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbid illnesses. Clinical studies have reported rates of obesity in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder of up to 60% (Reference McElroyMcElroy 2009). Those with severe mental illness have increased rates of medical conditions connected with obesity, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome (Reference SimsSims 1987).

Weight loss surgery has been shown in the USA to reduce overall mortality by 40% over a mean 7 years. The same study showed that there was a 56% reduction in death from coronary artery disease, a 92% reduction for those with diabetes and a 60% reduction in death from cancer after gastric bypass surgery (Reference Adams, Gress and SmithAdams 2007).

Patients can access information on surgery through a range of online resources, such as the British Obesity Surgery Patient Association (www.bospa.org).

Psychological morbidity among those seeking bariatric surgery

Early studies failed to identify obesity as a risk factor for psychiatric illness (Reference Friedman and BrownellFriedman 1995), and more recent community population surveys have also cast doubt on the relevance of obesity to psychiatric illness. Researchers have suggested that comorbid physical illness explains any variance identified (Reference John, Meyer and Hans-JurgenJohn 2005). Indeed, Reference Stunkard, Wadden, Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and AndreasonStunkard & Wadden (2000) argued that ‘although there have been many reports of emotional disturbance amongst the obese, numerous careful studies have shown little difference in psychopathology as compared with non-obese people in the general population’. These findings contrast with an emerging evidence base identifying high rates of depression, binge eating and other psychiatric disorders in patients seeking dietary or surgical treatment. Rates of lifetime psychiatric disorder have been identified to be as high as 66% among bariatric surgery candidates in the USA (Reference Kalarchian, Marcus and LevineKalarchian 2007). Reference Herpertz, Kielmann and WolfHerpertz and colleagues (2004) estimated that rates of Axis I disorders among those waiting for surgery vary from 27.3 to 41.8%, with mood disorder being the most prevalent.

Given these high rates of psychiatric comorbidity in patients presenting for surgery, and the potential for postoperative psychological complications, NICE recommends that a multidisciplinary team with psychiatric or psychological expertise carefully selects candidates for bariatric surgery (Box 1). Potential patients should undergo a comprehensive preoperative assessment of any psychological factors that may affect adherence to postoperative care requirements, including changes to diet. The guidelines emphasise that the patient should commit to long-term follow-up and that the multidisciplinary team should provide psychological support before and after surgery. However, at present there is no standard approach to psychological assessment.

BOX 1 NICE criteria for surgery

-

• The person’s BMI is 40 kg/m2 or more, or between 35 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2 with a significant disease (for example, type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure) that could be improved by weight loss

-

• All appropriate non-surgical measures have been tried for at least 6 months but have failed to achieve or maintain adequate, clinically beneficial weight loss

-

• The person has been receiving, or will receive, intensive management in a specialist obesity service

-

• The person is generally fit for anaesthesia and surgery

-

• The person commits to long-term follow-up

Despite there being no evidence base to guide clinicians as to which patients should or should not have surgery, many services exclude up to 20% of referrals, frequently on psychological/psychiatric grounds. A review of 81 US services identified considerable variance in what might be considered a contraindication. For example, 9% excluded patients who had been in prison and 26% considered admission to a psychiatric hospital in the past year as representing no contraindication (Reference Bauchowitz, Gonder-Frederick and OlbrischBauchowitz 2005).

Drawing on current evidence and the consensus of professionals working in bariatric teams, we provide an opinion and guidelines on the suitability of weight-loss surgery for people with mental illness.

Types of bariatric surgery

The three most commonly performed weight-loss operations offered to morbidly obese people are:

-

• laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding

-

• sleeve gastrectomy

-

• Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

When considering which type of surgery to offer an individual, specialist bariatric services will take into account patient choice and which procedure is considered the most beneficial.

Gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy appear to achieve weight loss primarily through restriction of stomach volume, whereas a gastric bypass brings about both restriction and early postprandial release of satiating gut hormones such as PYY and GLP-1 (Reference Bueter, Ashrafian and Le RouxBueter 2009).

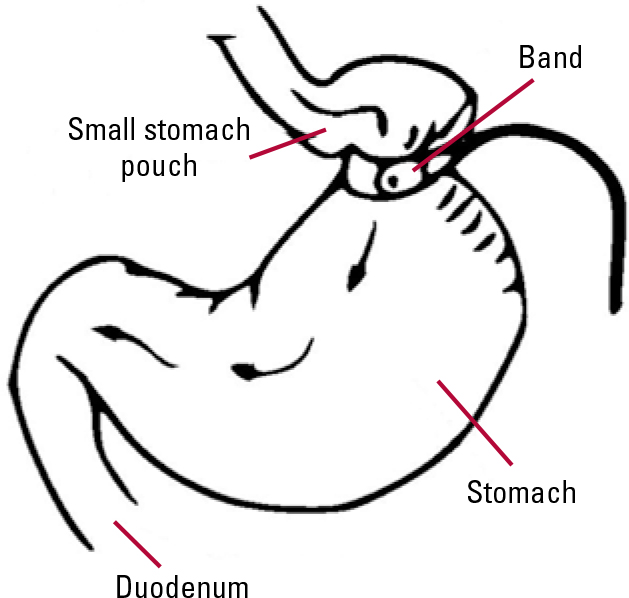

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding

During gastric banding, an adjustable inflatable silicone band is placed around the proximal part of the stomach (Fig. 1). The band can be inflated and deflated according to clinical need. The amount of restriction is reduced if patients experience vomiting and dysphagia and can be increased if there is insufficient weight loss. The procedure results in weight loss of around 15–20% over 15 years and requires regular follow-up (Reference Buchwald, Avidor and BraunwaldBuchwald 2004). Complications such as slippage of the band, erosion of the stomach wall by the band and dilatation of the stomach pouch occur in up to 25% of patients. Removal of the band resolves such problems but, in most cases, there is subsequent weight regain to former levels of obesity. Some studies have found psychological factors such as disordered eating in association with these complications (Reference Scholtz, Bidlake and MorganScholtz 2007).

FIG 1 Adjustable gastric band.

Sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy is a relatively new operation in which most of the stomach is removed to create a narrow conduit (Fig. 2). It is often offered to patients who have a BMI over 60 kg/m2, as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (below) is technically harder to perform at a higher BMI. Originally part of a two-stage procedure, with either conversion to gastric bypass or duodenal switch at a later stage, it may be suitable as a stand-alone intervention in some patients. Typical weight loss at 6-year follow-up is about 20%. Sleeve gastrectomy has similar effects on gut hormone release as gastric bypass surgery (Reference Peterli, Wölnerhanssen and PetersPeterli 2009).

FIG 2 Sleeve gastrectomy.

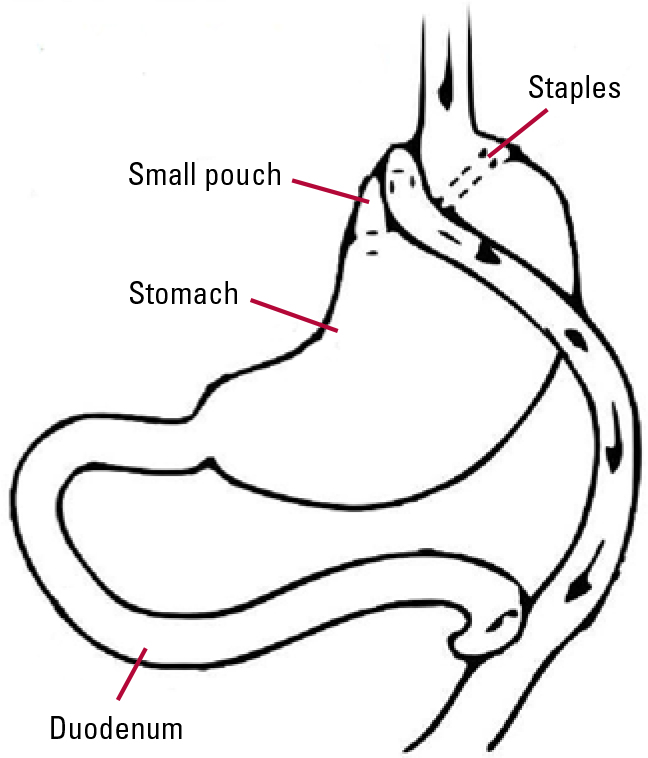

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Gastric bypass is, in our opinion, the gold standard of weight-loss surgery (Fig. 3) and brings about weight loss of around 30% at 15 years. It is associated with improvements in type 2 diabetes that appear to be weight-independent. Gastric bypass holds a higher surgical risk than the other two types of surgery described (mortality around 1 in 300 v. 1 in 1000) but this is comparable to the risk of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy and complication rates are possibly lower in centres of excellence. The procedure is most effective for those with type 2 diabetes. The higher risks reflect short-term operative complications, including pulmonary embolism, anastomotic leaks, bleeding, wound infection and haemorrhage. Both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass can lead to intestinal strictures in the longer term. Dumping syndrome (a complex neurohormonal disorder induced by eating concentrated sugars following gastric bypass) results in facial flushing, light-headedness, diarrhoea and fatigue. Gastric bypass causes malabsorption of some vitamins and micronutrients and is consequently associated with deficiencies in folate, B12, calcium, iron and other nutrients (Reference DeMariaDeMaria 2007).

FIG 3 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Postoperative gastrointestinal complications are common after all three procedures, with nausea, dysphagia and vomiting occurring in up to 50% of patients. This can be caused by overeating or excessive restriction as a consequence of the procedure.

The relative benefits and complications of each procedure are outlined in Table 1. There is much variance in surgical practice, and the procedures offered often reflect local experience and expertise. A Cochrane review of studies up to 2008 concluded that there was limited evidence on the comparative safety and effectiveness of these operations (Reference Colquitt, Picit and LovemanColquitt 2009). A detailed analysis of this area is beyond the scope of this article.

TABLE 1 Which type of surgery is most suitable?

Preoperative assessment

The bariatric multidisciplinary team may include upper-gastrointestinal surgeons, physicians, dieticians, anaesthetists, plastic surgeons, bariatric nurses and mental health professionals. Any decision to proceed with surgery will typically involve a risk–benefit analysis undertaken in a multidisciplinary meeting. Most centres require a surgical, anaesthetic and dietetic assessment to be carried out before surgery. The dietetic assessment will include an evaluation of nutritional adequacy. If hypothalamic and other endocrine causes of obesity are suspected or type 2 diabetes is poorly controlled, an endocrine assessment is done. The patient will have to make substantial post-operative changes to their diet and the amount and frequency of eating. Therefore, the assessment process places much emphasis on education and instilling appropriate expectations, helping patients to develop insight into their eating behaviour and to understand the behavioural changes necessary after surgery. Motivation for the operation will need to be assessed carefully. We believe that those seeking surgery to ‘treat’ underlying psychiatric disorders, as opposed to improving their mobility and physical health, pose a particular risk. Attendance at appointments and adherence to current treatment are considered by all members of the team, to assess commitment to change and long-term follow-up.

The NICE guidelines indicate that there is no evidence to support routine assessment by a mental health professional before bariatric surgery, although the assessment of psychological factors that might affect postoperative cooperation with treatment and follow-up and the need for psychological support before and after surgery are highlighted (National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care 2006). Mental health professionals are consequently inconsistently incorporated into bariatric surgical teams and the assessment of psychological factors may be undertaken by other members of the team. Nevertheless, many bariatric programmes have dedicated mental health professionals on the multidisciplinary team who may see all patients referred for surgery or a subgroup identified by screening. We recommend that all patients with a history of involvement with secondary mental health services should undergo a dedicated assessment by a mental health professional.

Even if a dedicated psychological evaluation and screening is included in preoperative assessment, there is considerable variation in practice (Reference PullPull 2010). Assessment will usually involve the domains outlined in Box 2 and often uses a structured assessment such as the Weight and Lifestyle Inventory (WALI; Reference Wadden and FosterWadden 2006).

BOX 2 Areas covered in routine psychosocial history

-

• Lifetime history of weight gain, including precipitating events

-

• History of weight-loss attempts

-

• Expectations from surgery

-

• Current eating habits and patterns

-

• Drug and alcohol use

-

• Past physical activity

-

• Past psychiatric history

-

• Current social circumstances

-

• Screening for current mental disorder, including depression and eating disorders

-

• Assessment of capacity

Psychiatric assessment and preparation for surgery

A psychiatric assessment to decide whether and when a patient with a mental disorder is eligible for bariatric surgery must cover a number of considerations. It should be seen as an opportunity to optimise mental health in preparation for surgery and to address and appropriately manage any identified risks. It should not be seen as a simple screen to exclude patients with mental health problems. The assessment will include a more detailed analysis of the domains outlined in Box 2, as well as a standard psychiatric history, mental state examination and cognitive assessment. Particular emphasis is placed on the chronology of weight change as an important clue to aetiology. For instance, dramatic weight gain after childhood sexual abuse might suggest an eating disorder, whereas weight gain after brain injury may suggest hypothalamic dysfunction and indicate the need for pituitary function tests.

Patient’s mental capacity and expectations

It is important to establish whether a patient has the mental capacity to understand the nature of the operation, its risks and its benefits. It is also necessary to assess whether the individual has realistic expectations of the results of surgery. The patient should be aware that weight-loss surgery is considered successful if 20–30% of body weight is lost. The most drastic weight loss occurs 6–12 months after surgery, after which body weight plateaus and some weight regain is normal (Reference Sjostrom, Lindrosos and PeltonenSjostrom 2004). Patients therefore may still be classified as obese after surgery, although their comorbid medical conditions and risks are significantly reduced. This degree of weight loss, although significant and sustained over time, does not always concur with the cosmetic or health aspirations of the patient.

Postoperative dietary adherence

It is important to identify any psychopathology that might affect adherence to the postoperative diet and acceptance of the need for life-long vitamins and follow-up. Weight-loss targets and food-diary monitoring can be used to assess motivational valence if there is doubt that the patient will be able to adhere to the rigorous postoperative dietary regimes.

All patients who have undergone bariatric surgery are at risk of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency. This is a particular risk with a gastric bypass, but is also seen in those who vomit after any restrictive procedure. Poor eating behaviour, food intolerance, vomiting and micronutrient malabsorption can lead to iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, folate and thiamine deficiencies (Reference Aasheim, Björkman and S⊘vikAasheim 2009). In a US study of 1663 patients who underwent biliopancreatic diversion, 2 patients developed Wernicke–Korsakoff encephalopathy 3–5 months after surgery (Reference ElliotElliot 2003), and a systematic review found 80 case reports of Wernicke’s encephalopathy after gastric bypass surgery (Reference AasheimAasheim 2008). These studies highlight the importance of adherence to multivitamin regimes to maintain nutrient levels.

An assessment framework

Using a system of red, amber and green, we suggest a framework for risk assessment that we have developed and incorporated into our practice (Box 3). This gives an indication of psychological risk to be balanced against potential benefits or risks in other domains as assessed by other members of the multidisciplinary team, and facilitates communication with the surgical team. We recommend that those who fall into the red zone are unlikely to benefit from bariatric surgery in the immediate future and those in the amber zone warrant careful multidisciplinary team discussion of the risks and benefits and may need further interventions to improve eligibility, such as treatment of underlying eating disorders.

BOX 3 A traffic-light system of preparedness for bariatric surgery

Red (not currently suitable for surgery)

|

Amber (possibly suitable, although deemed to be at higher risk)

|

Green (suitable for surgery)

|

Patients with unstable psychotic illness, current alcohol or drug dependence, severe personality disorder and/or severe cognitive impairment are not suitable for weight-loss surgery as they are not able to adhere to the rigorous postoperative regimes (Reference NorrisNorris 2007). There is a suggestion that those with a history of psychiatric admission have a poorer psychosocial outcome than those without (Reference Valley and GraceValley 1987).

It is particularly important that patients with severe and enduring mental health problems are concordant with treatment and have realistic expectations of the outcome. Care should be taken to ensure that adequate psychosocial support is in place for these patients both at the time of surgery and after the first 6 months or so, when weight loss tends to reach a plateau. Those with a history of serious self-neglect and self-harm are probably not suitable for surgery unless circumstances have changed to a degree where the chances of future self-neglect are deemed low. Those with unpredictable behaviour associated with psychotic symptoms are unlikely to be able to follow the complicated postoperative dietary changes needed. We therefore recommend that patients should not be considered for surgery unless over the previous 12 months they have had no relapses, characterised by unpredictable behaviour and functional impairment, and have adhered to treatment. We recommend that carers and a member of the local mental health team are consulted before surgery and agree a care plan to provide adequate practical support to the patient in the immediate postoperative period. In addition, increased frequency of contact, monitoring of medication or helping monitor for early signs of relapse are often recommended. These can help alleviate the stress of surgery and the loss of food as an emotional regulator.

Complications after surgery

In many ways, assessment is informed by the recognised complications of surgery (Box 4) that have been linked to mental health and identified through case reports and series. Many patients view surgery as a ‘last chance’, and although improvements in mental health are the norm (Reference Shiri, Gurevich and FeintuchShiri 2007), those who fail to lose weight, who are unable to tolerate the side-effects or who are otherwise dissatisfied with outcomes (particularly cosmetic) appear to be at particular risk. Suicide rates are higher in patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery compared with similarly obese individuals (Reference Adams, Gress and SmithAdams 2007), and psychiatric admissions may be more frequent (Reference Sarwer, Wadden and FabricatoreSarwer 2005). There are case reports of anorexia-type syndromes that have been dubbed ‘post-surgical eating avoidance disorder’ (Reference Segal, Kussunoki and LarinoSegal 2004). The evidence for the emergence of alternative addictive behaviours is less clear (Reference SoggSogg 2007).

BOX 4 Possible complications related to psychiatric disorder

-

• Relapse of psychiatric illness

-

• Suicide

-

• Amplification of self-induced vomiting

-

• Malnutrition

-

• Wernicke’s encephalopathy

-

• Relapse, exacerbation or increase in drug or alcohol dependency

-

• Post-surgical eating avoidance disorder or other forms of disordered eating, such as binge eating

Alcohol and drug dependence

Patients with current alcohol or drug misuse should not have bariatric surgery. We recommend that patients with a history of substance misuse demonstrate controlled use or abstinence for 12 months before surgery is considered. It is important to be aware that people with past or recent addictions may relapse or develop new addictions after surgery. It should be borne in mind that gastric bypass is likely to alter the metabolism of alcohol and enhance its effects (Reference Hagedorn, Encarnacion and BratHagedorn 2007). We recommend that those with a history of alcohol misuse do not receive malabsorptive procedures such as a gastric bypass, in view of the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy in the event that they restart excessive drinking.

Binge-eating disorder

There is a high prevalence (10–50%) of binge-eating disorder in patients referred for obesity surgery (Reference NorrisNorris 2007). Ideally, active binge eating should be treated before surgery because there is a putative risk that the patient will fail to lose weight after surgery (Reference LarsenLarsen 1990), although the evidence for this is inconsistent (Reference Mitchell, Lancaster and BurgardMitchell 2001). Binge-eating disorder can resolve following surgery, but some studies have reported anorexia and bulimia after surgery. Reference Segal, Kussunoki and LarinoSegal and colleagues (2004) have described purging, restriction, rapid weight loss and body-image distortion as part of post-surgical eating avoidance disorder.

Childhood trauma

Patients seeking weight-loss surgery report high rates of childhood adversity (69%; Reference Grilo, Masheb and BrodyGrilo 2005) and sexual abuse (17%; Reference Gustafson and SarwerGustafson 2004). It is important to consider how patients have been affected by past events, as we believe that this can affect their insight into their eating behaviours. Many patients describe ‘comfort eating’ and obesity as a defence mechanism in response to past abuse. Alternative coping behaviours must therefore be discussed with them, and some will benefit from psychotherapy before and after surgery.

Personality disorders

The chaotic lifestyle seen in people with personality disorders may undermine cooperation with dietary change and follow-up. It is vital to ensure that patients can demonstrate enduring changes to maladaptive behaviours, including self-harm and other destructive behaviours. In these circumstances, we would consider that a period of stability of at least 12 months is needed.

Effects of bariatric surgery on psychotropic medication

The pharmacokinetics of psychotropics following weight-loss surgery remains poorly understood and there is a scant literature. Gastric banding may increase the time that drugs remain in the proximal part of the stomach, although there has been no systematic evaluation of psychotropic pharmacokinetics after the procedure. Most change is seen following more invasive procedures, such as gastric bypass. This can reflect altered pH and drug solubility, bypassing major portions of the upper gastrointestinal tract and reducing the surface area for absorption. In practice, pharmacists usually recommend changing from enteric-coated and delayed-release formulations.

Changes to absorption have been inferred from assessment of changes in dissolution of common psychiatric drugs following gastric bypass in a laboratory setting (Table 2), although dissolution alone does not predict therapeutic efficiency (Reference Seaman, Bowers and DixonSeaman 2005).

TABLE 2 Predicted impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on pharmacokinetics of psychotropic drugs

A Canadian review (Reference Taylor and MisraTaylor 2009) has suggested that some medications, especially lamotrigine, olanzapine, quetiapine and extended-release anti-depressants, may be poorly absorbed post-bypass and should be regularly monitored. Lithium presents particular risks of toxicity (Reference TrippTripp 2011) owing to its narrow therapeutic window, and levels should be closely monitored after bariatric surgery.

In practice, we have found that in most patients psychotropic medication does not need to be altered after surgery, but that caution should be exercised by monitoring therapeutic response.

Conclusions

General psychiatrists are likely to be presented with requests for opinions on the suitability of their patients for bariatric surgery. Many obese people with mental illness will benefit from weight-loss surgery, but careful preoperative assessment and selection are required. It is essential that this process does not discriminate against this group or delay access to surgery. Postoperative monitoring of patients’ medical and psychological states is important.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Following gastric banding, it is considered realistic for patients to lose:

-

a 100% of their excess weight

-

b 50–70% of their total body weight

-

d 20–30% of their excess weight

-

e 100% of their total body weight

-

c 20% of their total body weight.

-

-

2 Following gastric bypass, there is increased absorption of:

-

a fluoxetine

-

b sertraline

-

c clozapine

-

d olanzapine

-

e none of the above.

-

-

3 It is an absolute contraindication to Roux-en-Y bypass if a patient has:

-

a severe mental illness

-

b current alcohol dependence

-

c mild intellectual difficulties

-

d history of an eating disorder

-

e unrealistic expectations.

-

-

4 Complications/side-effects of a gastric band procedure do not include:

-

a dysphagia

-

b dumping syndrome

-

c vomiting

-

d haemorrhage

-

e erosion of the stomach wall.

-

-

5 The NICE criteria for bariatric surgery recommend that the patient has:

-

a a BMI greater than 30 with comorbid obesity-related illness

-

b a BMI greater than 35 without comorbid obesity-related illness

-

c undergone a successful trial of anti-obesity medication

-

d the ability to commit to long-term follow-up

-

e achieved a 5% weight loss using other methods.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | e | 3 | b | 4 | b | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.