Introduction

Advances in longevity imply that family members share a longer period of life, enabling many older adults to actively enact the grandparent role (Bengtson, Reference Bengtson2001). There are different roles that grandparents can take on in family life. In some families, grandparents are the primary care-giver for their grandchild (i.e. custodial grandparents). They take on this responsibility when the grandchild's parents are incapable of raising the child due to substance abuse, illness, incarceration, death or other reasons (Hayslip et al., Reference Hayslip, Fruhauf and Dolbin-MacNab2019). In other families, grandparents take on shared parental responsibilities to help raise the grandchildren (Glaser et al., Reference Glaser, Stuchbury, Price, Di Gessa, Ribe and Tinker2018). This might take place when adult children move back in because of financial hardship, job demands or educational obligations. A much more common arrangement, particularly in the European context, is supplementary grandchild care. It is defined as grandparents assisting with care to non-coresident grandchildren (Hank and Buber, Reference Hank and Buber2008). For example, grandparents look after the grandchildren to enable parents to go to work or give them a break from child-care responsibilities (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020). This form of grandparenting is becoming increasingly common, especially in response to the rising labour force participation of mothers (Igel and Szydlik, Reference Igel and Szydlik2011; Glaser et al., Reference Glaser, Di Gessa and Tinker2014). In this study, we focus on non-custodial grandparents who provide supplementary care to their grandchildren and examine how they experience looking after their grandchildren.

A prominent perspective in the non-custodial grandparenting literature is that most grandparents embrace the task of looking after their grandchildren (Carr and Utz, Reference Carr and Utz2020). It is a fulfilling and rewarding task as grandparents can strengthen the emotional bond with the grandchild as well as provide practical and emotional support to their children (Silverstein and Marenco, Reference Silverstein and Marenco2001; Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020). Looking after grandchildren has been found to benefit grandparents (for a review, see Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kang and Johnson-Motoyama2016). Studies have shown a positive impact of grandchild care on life satisfaction and quality of life (Moore and Rosenthal, Reference Moore and Rosenthal2015; Condon et al., Reference Condon, Luszcz and McKee2018; Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Glaser and Tinker2016a, Reference Di Gessa, Glaser and Tinker2016b; Bordone and Arpino, Reference Bordone and Arpino2019; Danielsbacka et al., Reference Danielsbacka, Tanskanen, Coall and Jokela2019) as well as a link between grandchild care and fewer depressive symptoms (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Glaser and Tinker2016a; Sheppard and Monden, Reference Sheppard and Monden2019). Kahneman and Krueger (Reference Kahneman and Krueger2006) explain, however, that such global assessments of wellbeing offer an evaluation of life as a whole and are sensitive to several aspects of life (e.g. marriage, bereavement, unemployment). Consequently, such measures reveal little about activity-specific experiences (Chappell and Reid, Reference Chappell and Reid2002) and provide thus little direct insight into how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren.

A handful of small-scale quantitative studies have examined outcomes linked directly to grandparenting among non-custodial grandparents. These studies focus on role satisfaction (Somary and Stricker, Reference Somary and Stricker1998; Reitzes and Mutran, Reference Reitzes and Mutran2004; Moore and Rosenthal, Reference Moore and Rosenthal2015; Condon et al., Reference Condon, Luszcz and McKee2018), i.e. the extent to which grandparents are satisfied with the grandparent role. There seems to be support for the notion that grandparents embrace the grandparenting role. For example, Reitzes and Mutran (Reference Reitzes and Mutran2004) find that 94 per cent of the grandparents were (very) satisfied with their role, and this experience seemed to be universal as it did not differ by gender, health, education and marital status. However, qualitative studies show that grandparenting experiences are highly diverse. Although grandparents generally emphasise the rewards of grandparenting, they also hint at difficulties (e.g. Mason et al., Reference Mason, May and Clarke2017; Airey et al., Reference Airey, Lain, Jandrić and Loretto2021; Hamilton and Suthersan, Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021). For example, Hamilton and Suthersan (Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021) describe in their qualitative study on working grandparents that even though working grandparents enjoy looking after grandchildren, they report that it is tiring at times to combine their work and grandchild care obligations. Other qualitative studies find that grandparents generally report being able to care for their grandchildren is important to them, but they sometimes feel they do not have a choice and are pressured to do so (Horsfall and Dempsey, Reference Horsfall and Dempsey2013; Meyer, Reference Meyer2014; McGarrigle et al., Reference McGarrigle, Timonen and Layte2018). As such, it is important to not only focus on rewarding experiences in non-custodial grandparenting, but also to pay attention to the challenges associated with it to fully understand the heterogeneity in grandparenting experiences.

From previous quantitative research, it remains thus unclear to what extent non-custodial grandparents experience challenges in grandchild care. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the following question: to what extent do grandparents experience the provision of supplementary child care as burdensome and obligatory, and among which grandparents is this particularly the case? We focus on outcome measures directly linked to grandparenting to examine how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren. More specifically, we rely on survey data that asked grandparents to what extent they experience looking after their grandchildren as burdensome and obligatory. We expect that characteristics of the grandparenting context, as well as structural indicators of grandparents' opportunities for grandchild care (health, partner status, socio-economic status, alternative role engagements, gender), relate to these experiences. The analyses are based on large-scale data collected in 2015 and 2018 among Dutch older workers and recent retirees aged 60–68 years (N = 6,793), of whom 3,429 are grandparents who look after their grandchildren.

This study took place in the Netherlands, where formal child care is widely available (Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Cloin and Merens2014; Roeters and Bucx, Reference Roeters and Bucx2018). Around half of pre-school-aged children attend formal child care at least one day a week and around 40 per cent of them are also cared for by their grandparents (Roeters and Bucx, Reference Roeters and Bucx2018). With young mothers being stimulated to increase participation in paid work, grandparents will become more likely to face requests to assist with child care (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, van Tilburg, Poortman and Dykstra2015).

Explaining burden and obligation in grandparenting

Role strain theory (Pearlin, Reference Pearlin and Kaplan1983, Reference Pearlin1989) provides the theoretical basis in this study for examining feelings of burden and obligation in grandparenting. The central idea of role strain theory is that social roles entail responsibilities, which individuals generally want to fulfil, especially if the role is meaningful. Some individuals may, however, perceive hardships and difficulties doing so. This is called role strain. Family scholars have used role strain theory to study role strain among parents (for a review, see Nomaguchi and Milkie, Reference Nomaguchi and Milkie2020) and informal care-givers to a frail person (e.g. Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013; Mello et al., Reference Mello, Macq, van Durme, Ces, Spruytte, van Audenhove and Declercq2017). In this study, we build on role strain theory to understand role strain among grandparents who look after their grandchildren.

Findings from qualitative research suggest that role overload and role captivity are central forms of role strain in grandparenting (e.g. Mason et al., Reference Mason, May and Clarke2017; McGarrigle et al., Reference McGarrigle, Timonen and Layte2018; Hamilton and Suthersan, Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021). Role overload describes a ‘condition that exists when demands on energy and stamina exceed the individual's capacities’ (Pearlin, Reference Pearlin1989: 245). Feelings of burden in grandparenting, as a manifestation of role overload, might result from a discrepancy between grandparents' responsibilities (i.e. what they have to do) and their resources such as energy and stamina (i.e. what they can do). Next, role captivity describes ‘an inescapable obligation to be and do one thing at the very time the individual wants to be and do something different’ (Pearlin, Reference Pearlin and Kaplan1983: 19). Feelings of obligation in grandparenting, as a manifestation of role captivity, might result from a discrepancy between grandparents' responsibilities (i.e. what they have to do) and their preferences (i.e. what they want to do).

Based on this theoretical line of reasoning, role strain can first of all be assumed to be related to characteristics of the grandparenting context. Looking after grandchildren frequently might become burdensome because it entails more routine child-care tasks as well as greater involvement in the upbringing of the grandchild (Meyer, Reference Meyer2014; Mason et al., Reference Mason, May and Clarke2017). Likewise, grandparents who look after young grandchildren might find it more burdensome because it involves more hands-on child care than when looking after older grandchildren, with whom grandparents might engage in more leisure activities (Horsfall and Dempsey, Reference Horsfall and Dempsey2013; Mansson, Reference Mansson2016). Also, grandparents with many grandchildren have to distribute their attention between grandchildren, which might be emotionally and physically challenging, and thus may contribute to feelings of burden and obligation (Meyer, Reference Meyer2014).

Moreover, feelings of burden and obligation might arise depending on how well grandparents can enact their role as grandparents. Grandparents might struggle to keep up with their grandchildren, play with them or perform physical child-care tasks when they lack relevant resources (Meyer, Reference Meyer2014). Being in good health might be an important resource for grandparenting. Research suggests that older adults with health problems find everyday activities more challenging and taxing (Eldadah, Reference Eldadah2010). For grandparents with health problems, grandparenting tasks might then appear more burdensome than for healthier grandparents. Another resource for grandparenting is the presence of a partner. Although a partner does not necessarily provide hands-on support with grandchild care (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020), having a partner indicates the potential of receiving practical and emotional support (Leopold and Skopek, Reference Leopold and Skopek2014), as well as a possibility of sharing grandparenting tasks. As such, grandparents with a partner might experience grandparenting as less burdensome and obligatory. Moreover, high socio-economic status (SES) has been suggested to represent an important resource for grandparenting (Arpino et al., Reference Arpino, Bordone and Balbo2018). Higher SES individuals have been found to be more capable of coping with stress and difficult situations (Meeks and Murrell, Reference Meeks and Murrell2001). So, higher SES grandparents might find it easier to deal with the stressors of grandchild care than lower SES grandparents (Mahne and Huxhold, Reference Mahne and Huxhold2015). They might therefore experience grandchild care as less burdensome and obligatory than lower SES grandparents.

Research shows that grandchild care occurs next to other roles, such as paid work (Lakomý and Kreidl, Reference Lakomý and Kreidl2015), informal care-giving (Zelezna, Reference Zelezna2018) or volunteer work (Arpino and Bordone, Reference Arpino and Bordone2017). Involvement in other activities might impose additional restrictions on grandparents, creating cross-pressures and dilemmas in terms of time and energy. In a qualitative study, grandparents reported that combining frequent grandchild care with paid work is exhausting and that they are sometimes conflicted between their grandparenting duties and their work commitments (Hamilton and Suthersan, Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021). Thus, grandparents in paid work might experience grandparenting as more burdensome and obligatory than non-working grandparents. A similar reasoning might apply to grandparents who provide informal care and volunteer work. They may also experience cross-pressures between their grandparenting role and their other unpaid productive role engagements.

Furthermore, several studies argue that women and men relate to the grandparenting role in different ways (e.g. Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020). The grandparenting role is generally more salient in women's lives (Mahne and Motel-Klingebiel, Reference Mahne and Motel-Klingebiel2012) since they have been socialised into the kin keeper role, i.e. to contribute to their families throughout their lives. In particular, in the cohorts of older workers studied, the traditional gendered division of work – where women were more involved in care-giving tasks and men worked more hours in paid employment – was still common (de Boer and Keuzenkamp, Reference de Boer and Keuzenkamp2009). Research shows that the nature of grandparenting tasks is gendered, with grandmothers performing more ‘hands-on’ grandchild care than grandfathers (Horsfall and Dempsey, Reference Horsfall and Dempsey2013; Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020; Hamilton and Suthersan, Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021). This division of tasks might make grandparenting more burdensome and obligatory for grandmothers than for grandfathers.

Design and methods

Sample

This study uses data from the NIDI Pension Panel Study (NPPS), a large-scale longitudinal study in the Netherlands among older workers (Henkens et al., Reference Henkens, van Solinge, Damman and Dingemans2017; Henkens and van Solinge, Reference Henkens and van Solinge2019). A random sample of older workers aged 60–65 who worked at least 12 hours a week was drawn from organisations participating in the three largest pension funds in the Netherlands. The first wave was collected in 2015 when 15,470 questionnaires were sent out, of which 6,793 were completed (response rate of 44%). Data for the second wave were collected in 2018 among the participants of Wave 1, of whom 5,316 respondents participated (response rate of 79%). For the analysis, we excluded respondents without grandchildren (N = 2,548) and those who never looked after grandchildren (N = 476) in both waves. Further, respondents with a missing value on the dependent variables in both waves were excluded (N = 340). Overall, our final analytical sample consists of 3,429 persons.

In general, item non-response was low (<4%), with a maximum of 8 per cent for our measure of wealth. For low item non-response, less rigorous techniques to impute missing values are acceptable (Little et al., Reference Little, Jorgensen, Lang and Moore2014). We, therefore, used single stochastic regression imputation (Stata version 14: mi impute chained, m = 1) (Enders, Reference Enders2010).

Measures

Grandparenting burden and stress

Grandparents were asked about their adverse grandparenting experiences with the questions: ‘To what extent is looking after grandchildren burdensome?’ and ‘To what extent is looking after grandchildren obligatory?’ Response categories for each outcome were 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = fairly, 4 = very. Given that few grandparents felt very burdened (Nperson-wave = 84) or very obliged (Nperson-wave = 57), we combined the categories ‘very’ and ‘fairly’.

Grandparenting context

To measure the grandparenting context, we use the frequency of grandchild care, having a young grandchild and the number of grandchildren. The frequency of grandchild care provision corresponds to the following response categories: daily, several times a week, weekly, monthly and a few times a year. Since the number of respondents providing daily grandchild care is small (Nperson-wave = 47), we combined it with the category several times a week. Moreover, grandparents were asked how many grandchildren they have younger than age 5, between 5 and 11, and aged 12 and over. We used their responses to this question to create two variables: the presence of young grandchildren (i.e. at least one grandchild younger than age 5) and the number of grandchildren (one grandchild, two to four grandchildren, more than five grandchildren).

Health status

We used a subjective measure of health, i.e. how grandparents rate their own health. The response categories ranged on a five-point scale from 1 = excellent to 5 = very poor. We reverse coded the response categories in such a way that higher values indicate better self-rated health.

Partner status

To assess the partner status, we used the response to the question of whether respondents have a partner, which has the following response categories: 1 = yes, I am married; 2 = yes, I co-habit with a partner; 3 = yes, I do have a partner, but we do not live together; 4 = no, I am single. We grouped the items into a dummy which indicated that respondents have a partner (either married, co-habitating or living apart).

Socio-economic status

We used educational attainment and wealth as indicators for socio-economic status. Respondents were asked about their highest level of education. We categorised the educational attainment in three categories: low (i.e. elementary school, lower vocational education), medium (i.e. lower general secondary education, intermediate vocational education, upper general secondary education) and high (i.e. higher vocational education, university). Next, wealth was assessed through the following question: ‘How large do you estimate your total wealth (own house, savings, stocks, etc. minus debts/mortgage) to be?’, with response categories ranging from 1 = less than €5,000 to 7 = more than €500,000. We combined the categories into high wealth (>€250,000), medium wealth (€50,000–250,000) and low wealth (<€50,000).

Work status

We distinguished between individuals working in career employment and those who retired based on whether respondents have made use of a retirement arrangement to exit career employment (e.g. early retirement). Those who did not make use of a retirement arrangement (i.e. career workers) were further distinguished into whether they work full-time (≥36 work hours) or part-time (<36 work hours). Among retirees, we distinguished further between those who work for pay in retirement (i.e. post-retirement workers) and those who entered full retirement. Overall, the measure for work status consists of four groups: career employment, full-time; career employment, part-time; post-retirement work; and full retirement.

Informal care-giving

Respondents were asked whether they provided informal care to a frail person. If so, they were asked about the frequency with the following response categories: 1 = daily, 2 = several times a week, 3 = about weekly, 4 = about monthly, 5 = a few times a year. We grouped respondents into three categories: no care-giving, infrequent care-giving (i.e. monthly or less often) and frequent care-giving (i.e. at least weekly).

Volunteering

Respondents were asked whether they volunteered in an organisation. If so, they were asked about the frequency with the following response categories: 1 = daily, 2 = several times a week, 3 = about weekly, 4 = about monthly, 5 = a few times a year. We grouped respondents into three categories: no volunteering, infrequent volunteering (i.e. monthly or less often) and frequent volunteering (i.e. at least weekly).

Gender and age

We also added gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and age (in years) in our model. Table 1 presents the proportion/mean for the dependent and independent variables used in the analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables

Notes: The descriptive statistics are based on the person-wave observations prior to imputation: N = 4,205. SD: standard deviation.

Analytical strategy

We estimated two separate ordinal logistic regression models (Winship and Mare, Reference Winship and Mare1984) to examine feelings of burden and obligation among grandparents who look after their grandchildren. Ordinal logistic regression is best suited to our data, given the ordinal nature of our dependent variables. This method estimates the odds that a respondent with a specific value on the independent variable will be observed in a higher category on the dependent variable. Coefficients from ordinal logistic regression models are generally difficult to interpret because they are calculated as log-odds ratios. We exponentiated the coefficients to convert them into odds ratios (OR). ORs above 1 indicate increased odds and ORs below 1 indicate decreased odds.

Given the panel structure of our data, grandparents were represented twice in the data when they looked after their grandchildren in both waves of data collection (Nperson-wave = 5,076). To overcome the issue that observations of the same person are correlated, we added a random effect term in our model. In a random-effects model, the coefficients are calculated by using information from within- and between observations (Johnson, Reference Johnson1995). As such, person averages are used to analyse the between-person difference. We can interpret the coefficients in the same way as in a cross-sectional model.

Results

Diversity in grandparenting experiences

The descriptive findings in Table 1 show how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren. Around one in five grandparents reports that looking after grandchildren is very or fairly burdensome and almost one in ten grandparents feels obliged to look after grandchildren. At the same time, it may be relevant to note that almost all grandparents in our sample (98%) report that they experience grandparenting as very or fairly gratifying. The correlation of burden, obligation and gratification (Spearman's rho) points to the fact that feelings of gratification are different from feelings of burden and obligation. While the correlation between burden and obligation is relatively high (rho = 0.37, p < 0.001), the correlations between gratification and burden (rho = −0.05, p < 0.01) and gratification and obligation (rho = −0.15, p < 0.001) are much lower. These descriptive findings support the notion that challenging experiences can co-exist with positive experiences.

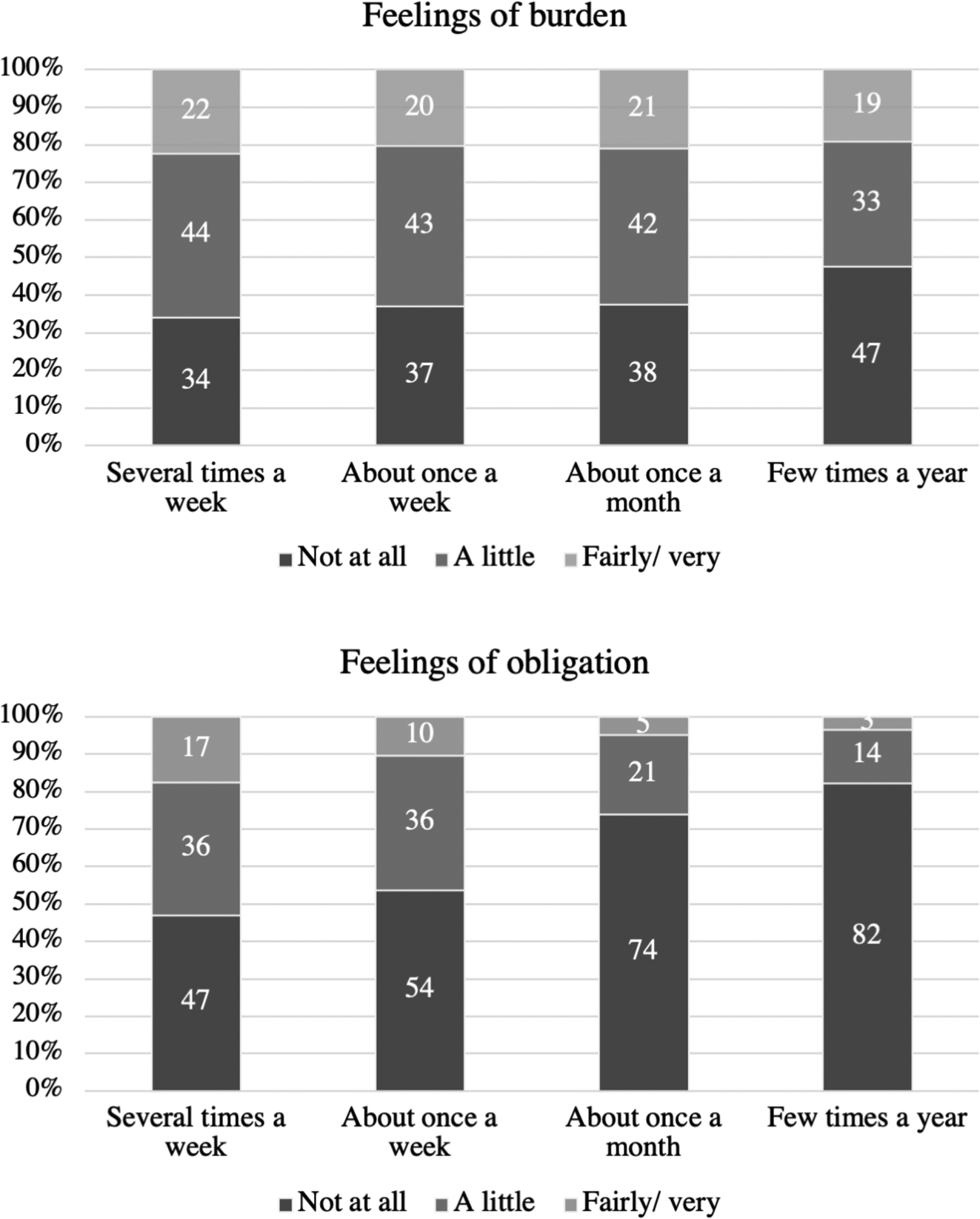

In Figure 1, we illustrate the link between the frequency with which grandparents look after their grandchildren and levels of grandparenting burden and obligation. The upper panel shows the proportion of grandparents experiencing grandparenting as very/fairly, a little and not at all burdensome by grandparenting frequency. Around one in five grandparents who look after their grandchildren several times a week experience it as very/fairly burdensome. The proportion of grandparents who experience grandparenting as very/fairly burdensome remains somewhat similar when grandparenting takes place less frequently. For example, around 21 per cent of grandparents who look after their grandchildren about once a month experience it as very/fairly burdensome. The lower panel of Figure 1 shows how perceived levels of obligation differ by grandparenting frequency. The variation in levels of obligation by grandparenting frequency is pronounced. Among grandparents who look after their grandchildren several times a week, 18 per cent experience it as obligatory. The proportion is lower when grandparents look after their grandchildren less frequently. For example, 5 per cent of grandparents who look after grandchildren once a month experience it as very/fairly obligatory.

Figure 1. Feelings of burden and obligation by frequency of grandchild care.

Note: The descriptive statistics are based on the person-wave observations prior to imputation: N = 4,205.

Predictors of feelings of burden and obligation

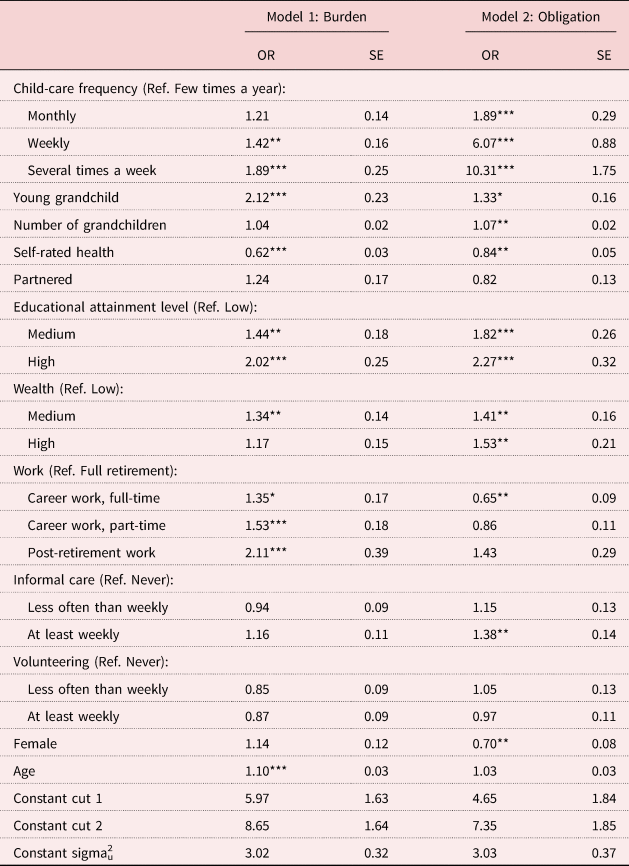

Table 2 presents the results of the random-effects ordinal logistic regression models for explaining feelings of burden (Model 1) and obligation (Model 2) in grandparenting. Overall, the results show that the grandparenting context, grandparents' characteristics and engagement in other activities were linked to levels of grandparenting burden and obligation.

Table 2. Random-effects ordinal logit models for explaining feelings of burden and obligation in grandparenting

Notes: N = 3,429. Number of person-wave observations = 5,076. OR: odds ratio. SE: standard error. Ref.: reference category.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The results were partly in line with our expectation that the intensity of the grandparenting context is linked to higher levels of grandparenting burden and obligation. Compared to grandparents who look after their grandchildren a few times a year, grandparents who do it more regularly were more likely to experience higher levels of burden and obligation. For example, the odds of experiencing high levels of burden were two times higher, and the odds of experiencing high levels of obligation were ten times higher for grandparents who look after their grandchildren several times a week than for grandparents who do it a few times a year. Next to the grandparenting frequency, we also found that the age of the grandchildren was significantly linked to higher levels of burden and obligation. Grandparents with grandchildren younger than age 5 were more likely to experience higher levels of burden and obligation compared to grandparents with older grandchildren. The number of grandchildren was, however, unrelated to levels of burden but was significantly linked to higher levels of obligation. The more grandchildren grandparents had, the greater was the likelihood of experiencing higher levels of obligation.

Grandparents' characteristics were also associated with levels of burden and obligation. The findings show that the better grandparents rated their health, the less likely they were to experience higher levels of burden and obligation. In contrast to our expectations, we find that the presence of a partner was unrelated to levels of burden and obligation. Next, we found that higher SES was significantly linked to levels of burden and obligation. Yet, unlike our expectations, we found that higher-educated grandparents were more likely to experience higher levels of burden and obligation than their lower-educated counterparts. Also, grandparents with high wealth were more likely to experience higher levels of obligation than grandparents with lower wealth levels.

Furthermore, we found that engagement in paid work was associated with higher levels of burden and, to some extent, also levels of obligation. Grandparents in full-time career employment were more likely to experience higher levels of burden but lower levels of obligation than fully retired grandparents. Also, grandparents in post-retirement paid work were more likely to experience higher levels of grandparenting burden, but not obligation, than fully retired grandparents. For informal care-giving, we found that it was unrelated to levels of burden but significantly linked to higher levels of obligation. Grandparents who provide informal care to a dependent person at least weekly were more likely to experience higher levels of obligation in grandparenting than those without any informal care duties. We found no statistically significant differences in levels of burden and obligation between grandparents who are engaged in volunteering and those who are not.

Turning to demographic differences in feelings of burden and obligation in grandparenting, we found that the older grandparents were, the more likely they were to experience higher levels of burden but not obligation. Next, we found no statistically significant gender differences in levels of burden. Grandmothers were as likely as grandfathers to experience higher levels of burden. However, grandmothers were less likely to experience high levels of obligation than grandfathers. In additional analyses, we tested whether the effects of the grandparenting context, grandparents' characteristics and grandparents' other engagements differ by gender. We found that the interaction term of gender and frequent informal care was significantly linked to higher levels of grandparenting burden (ORinteraction = 1.62, p < 0.01, not reported in Table 2). Grandmothers who provide frequent informal care were relatively more likely to experience greater levels of burden.

Discussion

Grandparenthood is one of the most salient roles in later life (Leopold and Skopek, Reference Leopold and Skopek2015), and many grandparents actively enact this role (Hank and Buber, Reference Hank and Buber2008). The most common form of grandchild care in a European context is non-custodial grandparenting, i.e. grandparents assisting with grandchild care when parents are away, e.g. at work (Hank and Buber, Reference Hank and Buber2008). Existing quantitative research on how grandparents fare when looking after their grandchildren has mainly focused on general wellbeing indicators (for a review, see Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kang and Johnson-Motoyama2016). Global assessments of wellbeing offer an evaluation of life as a whole but might be sensitive to several aspects of life such as marriage, bereavement and unemployment (Kahneman and Krueger, Reference Kahneman and Krueger2006). Consequently, such measures only indirectly provide insights about grandparenting experiences. Qualitative research has shown that how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren is more diverse than previous quantitative research suggests. This study is among the first to provide direct insights into how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren by examining challenging grandparenting experiences with large-scale quantitative data. Our aim is to examine the extent to which grandparents experience the provision of supplementary child care as burdensome and obligatory, and to assess among which grandparents particularly this is the case.

Our direct investigation of grandparenting experiences reveals considerable heterogeneity in how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren. While nearly all grandparents (98%) in our study indicated that they experienced grandchild care as fairly or very gratifying, one in five grandparents experienced looking after grandchildren as burdensome, and almost one in ten experienced it as obligatory. These challenging experiences were, however, only weakly correlated with feelings of gratification in grandparenting. Gratifying and challenging experiences seem to not represent opposites on the same dimension but can occur simultaneously. In other words, grandparents who experience grandchild care as gratifying might, nevertheless, find it challenging. This idea of a ‘dual nature’ of experiences is, in fact, well known in the literature on parenting (Nomaguchi and Milkie, Reference Nomaguchi and Milkie2020) and has also been identified for informal care-giving (Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013; Grünwald et al., Reference Grünwald, Damman and Henkens2021a). Our findings suggest that also grandparenting experiences are diverse.

Feelings of burden and obligation seem to be common challenging experiences in grandparenting. Perceived obligation of grandparenting was strongly associated with grandparenting frequency, i.e. grandparents who look after their grandchildren more frequently experienced it as more obligatory. This finding extends previous research (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020), which has found that substantial proportion of grandparents (17%) provide grandchild care because they find it difficult to refuse, by showing that feelings of obligation arise especially when frequent grandchild care is provided. The association between frequency and feelings of burden was much less pronounced. Almost as many grandparents who look after their grandchildren several times a week (22%) experienced it as burdensome as grandparents who did so once a month (21%) or less frequently (19%). This finding seems to suggest also that grandparents who provide less-frequent child care can perceive it as burdensome. As such, the perceived burden might be rather about the act of grandchild care itself than about the frequency of doing it. Furthermore, we found that grandparents with grandchildren under the age of 5 reported higher levels of burden than those with older grandchildren. We can only speculate based on qualitative research findings that feelings of burden arise among grandparents with younger grandchildren because they have to provide more hands-on child care, whereas grandparents with older grandchildren can engage in more leisure activities (e.g. Horsfall and Dempsey, Reference Horsfall and Dempsey2013; Mansson, Reference Mansson2016). Additional research is needed to determine which specific grandparenting tasks contribute to feelings of burden in grandparenting.

Our findings further show that grandparents' characteristics were associated with feelings of burden and obligation in grandparenting. While the impact of health status was as expected (i.e. grandparents in poor health experience higher levels of burden and obligation), the effects of higher SES pointed in the opposite direction than initially expected. We find that feelings of burden and obligation are more widespread among higher-SES grandparents, both regarding wealth and education. These findings seem to contradict expectations that, for example, higher-educated grandparents face fewer challenges in grandchild care since they have more opportunities and knowledge to enact the grandparenting role (Silverstein and Marenco, Reference Silverstein and Marenco2001). As higher-educated individuals have been found to engage in more diverse leisure activities (Stalker, Reference Stalker2011) and are more socially integrated (Gesthuizen et al., Reference Gesthuizen, van der Meer and Scheepers2008; Serrat et al., Reference Serrat, Scharf, Villar and Gómez2020), they might be more conflicted between their grandparenting responsibilities and pursuing other interests than lower-educated individuals. They might thus struggle to find ways to balance these roles in later life when facing increasing expectations to be active and to contribute to society (Serrat et al., Reference Serrat, Scharf, Villar and Gómez2020).

Moreover, we expected that grandparents' engagement in other activities, particularly paid work, would relate to higher levels of experienced grandparenting burden and obligation. Our findings show that paid work has a differential impact on how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren. We found that grandparents in full-time career employment experienced higher levels of burden but lower levels of obligation compared to fully retired grandparents. This finding seems to suggest that paid work and grandchild care before retirement might be difficult to balance, but at the same time, full-time career employment might protect grandparents from normative expectations to engage in grandchild care. Research has shown that grandparents are likely to increase their engagement in grandparenting after leaving career employment irrespective of whether they remain engaged in some kind of post-retirement paid work (Grünwald et al., Reference Grünwald, Damman and Henkens2021b). This study extends this notion by showing that grandparents seem to find grandparenting relatively burdensome when they work in retirement. Post-retirement work seems to still contribute to grandparenting burden, although these jobs are typically more flexible and require fewer work hours than career jobs (Dingemans et al., Reference Dingemans, Henkens and van Solinge2016). As older adults are increasingly stimulated to prolong employment and at the same time are expected to contribute to their families (Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Woittiez, Eggink and Putman2014; van Solinge and Henkens, Reference van Solinge and Henkens2017), increasing numbers of older adults may face a challenging combination of engagements.

Although grandmothers have been found to perform more ‘hands-on’ grandchild care than grandfathers (Di Gessa et al., Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020; Hamilton and Suthersan, Reference Hamilton and Suthersan2021), the results of this study show that grandmothers do not seem to be more likely to experience grandchild care as challenging. There were no differences in grandmothers' and grandfathers' feelings of burden but in feelings of obligation, with grandmothers being less likely to perceive grandparenting as obligatory. This might suggest that grandmothers may have internalised expectations about grandchild care. Yet, we find that grandmothers experience grandchild care as relatively burdensome when they perform it in combination with frequent informal care. This finding extends previous research, which has found that care activities accumulate (Zelezna, Reference Zelezna2018), by showing that this accumulation is experienced as burdensome among the studied women.

Taken together, the results of this study show that the situations from which feelings of burden and obligation arise are complex. It seems to be not only about the intensity of the grandparenting context but also about the characteristics of the grandparents and their other responsibilities. Role strain theory (Pearlin, Reference Pearlin and Kaplan1983, Reference Pearlin1989) suggests that challenging experiences might result from a discrepancy between grandparents' responsibilities and their resources and preferences. Future quantitative research might consider directly examining these mechanisms that could give rise to role strain in grandparenting, for instance, by directly asking respondents about their preferences regarding grandparenting and by examining changes in grandparenting experiences over time. For example, Di Gessa et al. (Reference Di Gessa, Zaninotto and Glaser2020) also found that substantial numbers of grandparents look after grandchildren because they find it difficult to refuse.

This study has some noteworthy strengths. Our measures of grandparenting experiences among a large sample of grandparents allowed us to examine the extent to which grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren as burdensome and obligatory. Moreover, our findings contribute to identifying the conditions from which these feelings originate and identifying the grandparents who are at risk of experiencing grandparenting as challenging. However, when interpreting the study findings, also some limitations should be borne in mind. First, our measures of burden and obligation are single items, which may have limited our ability to capture the full range of grandparenting burden and obligation. Second, we were not able to control for important characteristics of the grandparenting situation, such as distance to grandchildren, quality of the relationship with (grand)children, and activities that grandparents engage in with their grandchildren. Also, we had no information on the availability and use of formal child care. Third, we used self-rated health to measure health status but lack more specific information on grandparents' capacity to look after grandchildren, such as information about limitations in (instrumental) activities of daily living and mental health. Fourth, our data offer information on working grandparents and recently retired individuals but are not nationally representative for all non-custodial grandparents who are looking after their grandchildren. Fifth, this study takes place in the Netherlands, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other countries where child care is differently arranged (European Commission, 2018). In countries with limited access to formal child care, demand for grandchild care may be greater, which may result in more grandparents facing challenges in looking after grandchildren.

As maternal labour market participation rates rise, so does the need for child care (Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2000). Grandparental child care is often considered the ‘next best thing’ to parental child care and, thus, many grandparents look after their grandchildren regularly. Understanding how grandparents experience looking after their grandchildren is important. Our study clearly shows that grandparenting has two sides – it is a gratifying experience, but it can be burdensome and obligatory for some grandparents. Future cohorts of grandparents might increasingly face challenges when looking after their grandchildren in light of the policy priorities of stimulating both employment and social engagement in later life.

Financial support

This research was supported by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (KH, VICI-grant 453-14-001; MD, VENI-grant 451-17-005); and Netspar.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required.