Background

Facilitating independence for older people is an important outcome for health and social policy and has been for decades (Dant, Reference Dant1988; Department of Health, 2005; Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy, 2021) both in the United Kingdom (UK) and internationally (Plath, Reference Plath2009). As an essential aspect of self-management (Abdi et al., Reference Abdi, Spann, Borilovic, de Witte and Hawley2019) and person-centred care (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Foot and Humphries2014), supporting people to maintain independence offers an opportunity to curb the rising costs of health and social care (Secker et al., Reference Secker, Hill, Villeneau and Parkman2003; European Commission, 2021). More than simply an outcome or cost-saving policy, for many people independence is a valued way of life (Kelly, Reference Kelly2003). The importance of independence to older people has been widely documented (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2003; Secker et al., Reference Secker, Hill, Villeneau and Parkman2003; Meza and Kushner, Reference Meza and Kushner2017; Abdi et al., Reference Abdi, Spann, Borilovic, de Witte and Hawley2019) and advocated by patients’ organisations (National Health Service, 2014). Being independent is associated with feelings of freedom, pride, self-worth and competence (Haak, Reference Haak2002). Independence, therefore, has a key role to play in improving and facilitating personal wellbeing.

However, the meaning of independence is ill-defined and a consensus is lacking about what it means to be independent (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014; Bell and Menec, Reference Bell and Menec2015). In the few attempts that have been made to conceptualise independence, the perspectives of older people are notably missing (Åberg et al., Reference Åberg, Sidenvall, Hepworth, O'Reilly and Lithell2005). Existing conceptualisations of independence focus on specific aspects of independence such as receipt of care (Secker et al., Reference Secker, Hill, Villeneau and Parkman2003), disability (Gignac and Cott, Reference Gignac and Cott1998) or ageing in place (Haak et al., Reference Haak, Fänge, Iwarsson and Ivanoff2007), which are pertinent to the field of the academics, service providers or policy makers defining them but which may not be relevant to older people. Understanding what independence means to older people and how that independence can be facilitated has been identified as a research priority by patient, family and professional stakeholders because of its potential to inform and improve practice and health outcomes (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Corner, Laing, Nestor, Craig, Collerton, Frith, Roberts, Sayer, Allan, Robinson and Cowan2019).

By generating understanding of how older people perceive what independence means and how it is facilitated, this study is designed to address the identified gap in knowledge and provide insight that will directly benefit person-centred support for independence.

The objectives of the study were:

(1) To understand what independence means to community-dwelling older people aged 75 years and over.

(2) To identify the facilitators that community-dwelling older people feel are most important for achieving and maintaining their independence.

(3) To consider how individual perspectives on independence can usefully inform the operationalisation of person-centred care.

Methods

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the South West Peninsula and Yorkshire sites of the Community Ageing Research 75+ (CARE75+) cohort study (Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Brown, Young, Teale, Hawkins, Spilsbury, Mountain, Young, Goodwin, Hanratty, Chew-Graham, Brundle, Mahmood, Jacob, Daffu-O'Reilly and Clegg2019). The CARE75+ study is a recruitment platform for research with older people who can optionally consent to be approached about other studies when joining CARE75+. The CARE75+ cohort includes community-dwelling older adults, aged 75 years or more, from seven sites across England. CARE75+ participants include people across the spectrum of health and frailty, and from varied ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. Contrasting levels of affluence, main sources of industry and ethnic diversity between the two selected sites make it possible to explore the potential impact of place on independence and further deepen our understanding of independence (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014). The rationale and outline of the methods used for this qualitative study were presented to, and approved by, the CARE75+ Frailty Oversight Group (FOG). Comprised of four individuals with extensive links to relevant local community structures, the FOG provides a key reference group with a monitoring, scrutiny and advocacy role on behalf of CARE75+ participants (Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Brown, Foster and Clegg2016).

We sampled purposively, with an aim for maximum variance in demographic attributes such as: gender, age, living circumstances, and rural or urban setting. Recommended sample sizes for phenomenological studies, which aim to explore meaning, suggest that the recruitment of eight to ten participants has been successful to obtain sufficient depth and richness of data (Hennink et al., Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Marconi2017; Creswell and Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2018), providing a guide to the sample size necessary for this study, also seeking to explore meaning. Taking the eight to ten sample as a baseline, we considered aspects that would increase ‘information power’ (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016) in our study. The following actions generated information power by ensuring that the data gathered had strong relevance and provided rich understanding for answering the questions of this study. Pilot interviewing improved the standard of dialogue and therefore richness of the data. Underpinning the approach with a theoretical lens increased the explanatory power, and narrowing the scope of discussion to the single concept of independence increased the depth of information that could be generated for this topic. Weighing these attributes against aspects of the study that could reduce ‘information power’, such as the aim to use cross- as well as within-case analysis and some heterogeneity within the sample, we concluded that an ideal sample for our study was likely to be between 15 and 20 participants. We reviewed the initial appraisal of sample size (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016) through discussion with the research team following the first three interviews and agreed that the data contained sufficient information power to generate rich understanding about how the meaning of independence developed in the contexts of the study participants.

Sampled participants were sent an invitation to participate via a letter which included details of the study and a consent form. Recipients of the invitation who did not respond were followed up with a phone call and additional participants with similar demographical attributes were approached to take the place of those who had been sampled but declined to take part.

In addition, details of the study were included in the regular newsletter sent out to all CARE75+ participants, enabling individuals to volunteer themselves for the study. Volunteer participants were recruited into the study if their demographic characteristics were similar to a participant who had already declined to take part. Participant details, including records of consent, were stored in password-protected folders on a secure server and were identified using identification codes rather than names to maintain confidentiality.

Data collection

Letters were sent to 16 people purposively sampled from the CARE 75+ cohort, ten of these declined to take part in the interview study. Reasons for not wishing to take part included: feeling ‘too old’, managing poor health, hearing or visual difficulties, and feeling uncomfortable with telephone interviewing. Eight participants responded to the newsletter article, all of whom were accepted to take the place of participants who had declined to take part as their demographic characteristics continued to support variance within the sample. It was not necessary to turn any newsletter-generated participants away based on this criteria. Notably, all the participants approached who lived with family declined to take part and no newsletter respondents lived with family.

Fourteen people took part in the study, ranging in age from 76 to 98 years old, with a mean age of 82 (standard deviation = 5.25 years) (for demographic characteristics, see Table 1). Six participants responded to an invitation to the study via letter and eight responded having seen the notice in the newsletter. Six participants were recruited from the South West Peninsula sites of the CARE75+ cohort and the remaining eight were recruited from the Yorkshire sites.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of interview participants

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author (ET) over the telephone (N = 9) or via video call (N = 5), rather than face-to-face, due to COVID-19 UK Government-imposed restrictions (Prime Minister's Office, 2020). Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and both interviewer and participants attended the interview from their own homes. Semi-structured interviews were used, as interviews lend themselves to understanding how participants think and feel about a phenomena, providing insight to participants’ internalised meanings and perceptions that could not be obtained through more observational methods (Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2014).

The interview guide (see the online supplementary material) was developed through a review of the literature, discussion with the research team, and was enhanced by Public and Patient Involvement and Engagement (PPIE). Obtaining input from research team members, experienced in various aspects of research with older people, and the literature review helped the lead author to consider the scope of independence, broadening her knowledge and diluting potential bias that could come from her experience working with older people in the third sector. The PPIE group informed the focus and improved the comprehensibility of the interview materials by suggesting amendments to the content and presentation which improved the relevance and readability of the materials.

Interview dialogue and ability to build rapport with interview participants has an impact on the power of information generated through interviews (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016). Conducting a pilot interview with an experienced qualitative researcher in the team, and receiving feedback from review of initial transcripts from research team members, augmented training already undertaken by the lead author, enabling improvement in the interview dialogue. Interviews were conducted from the lead author's home with precautions taken to maintain confidentiality. All interviews were recorded with participant's consent.

Data analysis

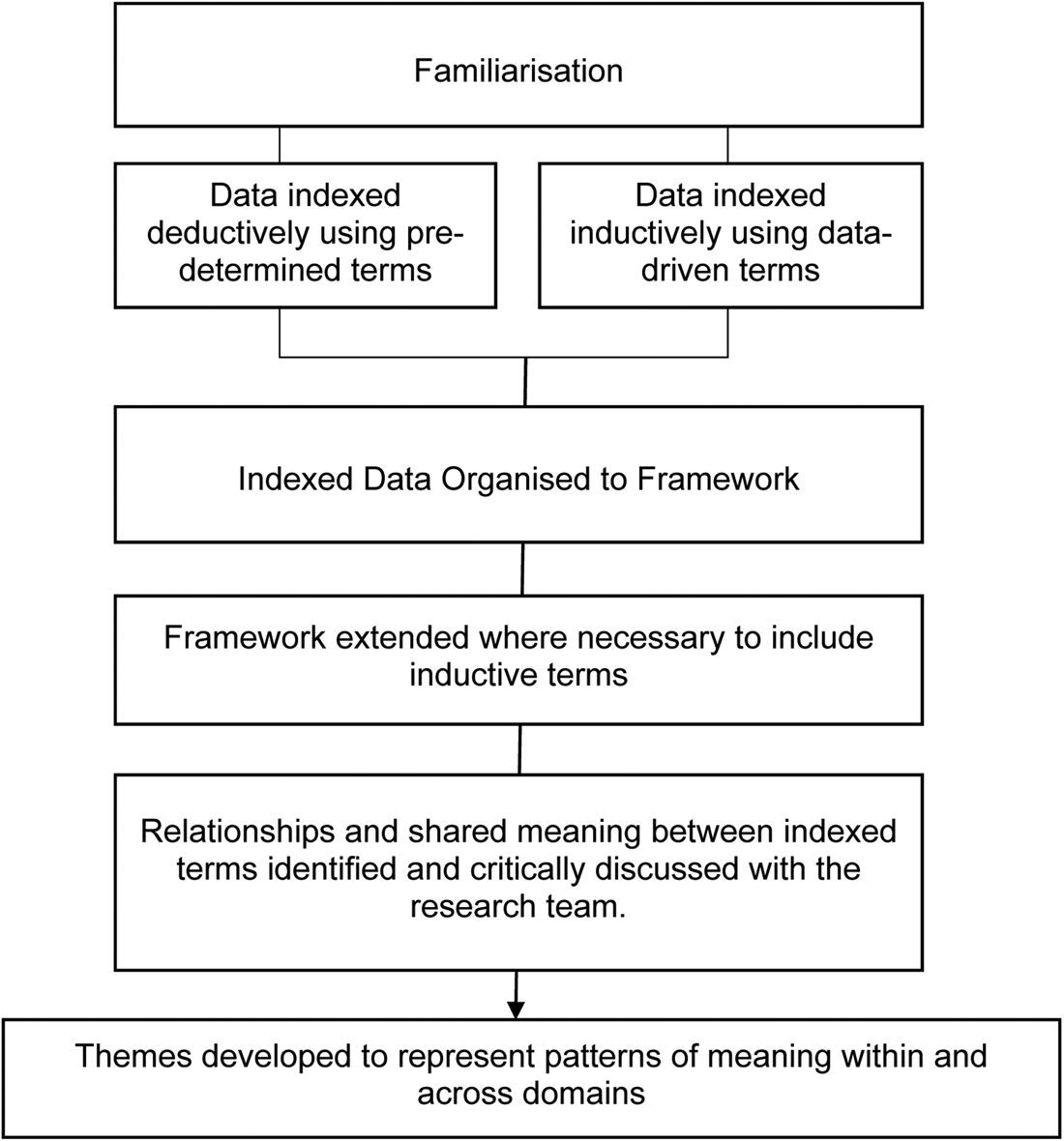

A Framework Approach to analysis was used following stages described by Ritchie and Lewis (Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003) and presented in Figure 1. To facilitate understanding of what independence means to older people, the analytical framework needed to be relevant and broad enough to capture the full extent of, and avoid predetermining, older people's perspectives. Existing conceptualisations of independence were considered for the framework but were narrow, focusing on the experience of independence in the context of disability (Gignac and Cott, Reference Gignac and Cott1998), receiving care (Hammarström and Torres, Reference Hammarström and Torres2010; Breitholtz et al., Reference Breitholtz, Snellman and Fagerberg2013; Barken, Reference Barken2019), or were determined from academic perspectives (Munnichs and van den Heuvel, Reference Munnichs and van den Heuvel1976) or secondarily from existing literature (Secker et al., Reference Secker, Hill, Villeneau and Parkman2003). The incongruence of existing frameworks and absence of direct input from older people, especially those not in receipt of care, in determining them, made it challenging to know which, if any, would be most appropriate for organising the views of older people interviewed for this study. The International Classification of Functioning (ICF) (World Health Organization, 2002) was selected as a relevant but more neutral framework with which to organise the analysis. The breadth covered by the domains of the ICF was comprehensive of many of the facets included in existing conceptualisations of independence but did not impose a predetermined construct of independence enabling the meaning of independence to be determined by the older people interviewed. The lead author checked, read and re-read the transcripts. Following familiarisation, the lead author used index terms to group and organise portions of text relevant to the research questions. The process of refining index terms to codes that captured the essence of meanings and organising these codes with the help of a framework enabled the lead author to identify patterns of shared meaning that were further developed into themes.

Figure 1. Analytical process based on the steps of the Framework Approach (Ritchie and Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003).

To improve understanding of independence through different forms of knowledge, index terms were derived inductively and deductively. Deductively derived index terms, from variables used to assess physical, psychosocial and health outcomes as part of the CARE 75+ study standard assessments, aimed to explore participants’ responses through a language and lens familiar to a health and social care setting. The index terms ‘falls’ and ‘informal support’ are examples of deductively derived codes and were derived from the assessment questions, ‘How many falls have you had in the last year?’ and ‘How many hours of unpaid support have you received in the last four weeks?’, respectively. These terms were assigned to portions of text (words, phrases or sentences) in which participants spontaneously talked about the impact of falls and/or unpaid support on their independence.

To provide a more expansive analysis of the data (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) unrestrained by pre-specified terms, the data were also explored inductively, with new codes being developed to capture the essence of elements, feelings or emotions described in the data that were pivotal to understanding the meaning of independence but would have been missed by the deductive codes alone.

Deductive index terms were organised by ICF domain then compared and grouped by similarity in meaning within those domains to develop refined codes. Codes generated inductively were added to the existing framework if this could be achieved without loss to their integrity and meaning. If the essential meaning of a code would be compromised by arbitrary incorporation into the existing framework, the framework was adapted to sensitively incorporate the full essence of the finding.

The a priori coding scheme and examples of inductive coding were shared and discussed with the research team. The range of personal and practice perspectives provided by the team enabled critical reflection and further refinement of codes. For example, if a code was ambiguous or there was disagreement as to whether the term truly captured the essence of the data it related to, agreement on a more suitable term was achieved through discussion.

The final step of the analysis involved moving beyond the presentation of the codes themselves, using the diagrammatic form as an aid (Ritchie and Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003), to explore, map and interpret the relationships and patterns between codes (Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2018). The lead author interpreted the meanings, relationships and patterns in responses, which related to the research questions, developing themes derived from the data. Returning to the original data to ask whether each theme was, indeed, a true fit for the data or whether there were ‘untidy bits’ or elements missing (Ritchie and Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003) not only helped to ensure coherence of themes, but encouraged deeper reflection on the data, enabling a richer interpretation. Regular meetings with the research team, who had also reviewed a proportion of the transcripts, further added to the integrity of the resulting themes. Figure 2 diagrammatically presents the themes and their underpinning concepts.

Figure 2. Diagram showing concepts underpinning themes and responding to the research questions.

Reflexive practice

Throughout data collection and analysis, the lead author made field notes and kept reflexive memos which added to the depth and credibility of the study findings. Field notes were used to document contextual data, such as the tone of the interview, and environmental factors, such as technological issues, which may have affected data collection. Analytical memos aided the analysis by recording potential links and associations between data for further exploration. Reflexive memos where the lead author noted any judgements, reactions or ‘gut feelings’ towards the data helped her to maintain awareness of her influence on the analytical process and to unpack any assumptions (Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2018) that may have stifled important lines of exploration.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted for this study by the University of Exeter Medical School Research Ethics Committee. The CARE75+ study was approved by the NRES Committee Yorkshire and Humber–Bradford Leeds (Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Brown, Young, Teale, Hawkins, Spilsbury, Mountain, Young, Goodwin, Hanratty, Chew-Graham, Brundle, Mahmood, Jacob, Daffu-O'Reilly and Clegg2019). Participants were informed of the measures taken to maintain confidentiality and their consent to voluntary participation was obtained both through informed written consent and verbally prior to the interview.

Results

Themes

Two major themes were identified. The first theme, ‘Older people draw on personal values and experiences to develop unique interpretations of independence’ is underpinned by three concepts that were common to each interpretation: participation, autonomy and control. The second theme, ‘It's not what you have, but how you think about it that creates independence’ comprises participants’ thoughts about what helps them to remain independent.

Theme 1: Older people draw on personal values and experiences to develop unique interpretations of independence

When asked about what independence meant to them, participants’ responses were diverse and often related to individual values and experiences. Even so, three concepts, participation, autonomy and control, were common to the participants’ interpretations of independence.

Participation – ‘I need to be doing things’

The concept ‘participation’, was developed from a common turn of phrase used by participants: ‘doing things’.

Independence means to me is how I can … still do a lot of the things that I want to do. (George, 84 years)

The broad term ‘doing things’ encompassed a range of hobbies, social and community activities, and was a key part of participants’ understanding of independence. For Henry and Bert, independence meant the stimulation of ‘doing’ their various hobbies and social roles within the community which had prevented boredom or disconnection following retirement:

Independence for me is, since retirement, being able to pursue a lot of my hobbies and paraprofessional interests … I like to keep fit, I like to do things that keep me moving … Plus singing plus gardening plus a lot of things that I do in the cricket world umpiring cricket. And being independent to me means being fit enough physically and mentally to do all those things. (Henry, 77 years)

Yeah, I need to be able to work even if it's hobbies and some of it is proper work because I do a lot of gardening, I do a lot on the bees … I like to be busy in my mind. (Bert, 78 years)

The importance of ‘doing things’ chimes with the tenets of activity theory and the understanding that engagement in activity has a positive impact on health and wellbeing in later life. However, the range of potential activities, as noted by Katz (Reference Katz2000), is vast. To refine our understanding it was necessary to look closer at which types of activity participants imagined ‘doing’ for their conceptualisations of independence. As articulated in participants’ quotes above, a pertinent defining feature of activity in relation to independence was doing things that the person ‘liked’ or ‘wanted’ to do.

Not all activities were given the same priority in their contribution to independence, as illustrated when Catharine was asked to define independence:

It is being able to be involved in organisations and really that's probably the most important thing … and of course being able to do our own shopping and things like that. (Catharine, 79 years)

In addition, when asked what independence meant to her, Catharine responded, ‘it's going around driving my car and doing all of the things that I love to do’. Whilst Catharine recognised the activity of doing shopping as an important part of her independence, her participation in organisations and pastimes that she ‘loved to do’ was ‘most important’ and given priority when asked about the meaning of independence. This prioritisation of desired activity over obligated or routine activity was shared by most of the participants and supports suggestions that the benefit of engagement with activity is not the same for all activity types (Lemon et al., Reference Lemon, Bengtson and Peterson1972; Knapp, Reference Knapp1977; Menec, Reference Menec2003). Some participants acknowledged that they did not engage in some forms of activity such as housework, meal preparation and shopping, because the activities did not interest them, were not their role or would reduce their time and energy for more engaging pastimes. Rather than being seen as a detriment to their independence, the choice to receive help and to prioritise participation appeared to reinforce a sense of independence.

Desired activities, whose ‘doing’ were so prominent in participants’ definitions of independence, were not limited to social or group activities, nor were they necessarily active pursuits. For some, it meant being able to go on holiday, for others it involved model-making, carpentry or being involved with a faith community. The value of a social element in activities was notably different between participants. Whilst participants often valued the stimulation of social engagement, for some participants the ability to choose not to attend social engagements was a key proponent to maintaining their independence and not feeling beholden to others:

Interviewer: How do you think that would help [your independence] joining in the activities?

R8: Well to keep your mind occupied for a start rather than watching the box all day which … no way! I think yeah that, and you know talking with different people, hearing their opinions and arguing with them but no, conferring. Putting the world to rights yes. That would take a lot of doing but yes. Yeah, I think you know going out with friends for a cup of coffee in the morning. (Tony, 80 years)

We would get a notice through our door all of us in the avenue from [name] and [name] ‘we are meeting distancing for a drink in the avenue’, this is like bring your cup of coffee, bring your own what and now so I did go and I went up I went a couple of times but yeah, I find, I found it a little bit it's not me … I am sociable but not I am not bothered about getting to know them too, I can't put I don't know how to put that but yes. So, I am as neighbourly as I want to be. (Nancy, 82 years)

Under the auspices of activity theory, each of the ‘doing things’ introduced by participants could be classed as activity (Katz, Reference Katz2000). However, the ICF framework used in this study provided language that enabled distinction of independence-defining activities from the wider range of possible activities. The ICF concept ‘participation’ is defined as ‘involvement in a life situation’ and is distinct from activity which relates to a more fundamental process of the execution of a task or activity (World Health Organization, 2002). Since, in this study, the distinguishing feature of independence-defining activity was that it brought meaning or pleasure to the participants’ life rather than simply being a routine activity necessary for daily living, the concept ‘participation’ effectively captures this essence of what participants meant by ‘doing things’. Being clear about the distinction between participation and activity highlights that many older people need more than just the ability to carry out routine activities of daily living (ADLs) to support a sense of independence, a finding that resonates with the results of Ravensbergen et al. (Reference Ravensbergen, Timmer, Gussekloo, Blom, van Eijk, Achterberg, Evers, van Dijk and Drewes2022).

Although measures of ability in ADLs are commonly used in health and social care (White and Groves, Reference White and Groves1997; Plath, Reference Plath2009; Ravensbergen et al., Reference Ravensbergen, Timmer, Gussekloo, Blom, van Eijk, Achterberg, Evers, van Dijk and Drewes2022) to provide empirical scores of independence, the association between ADLs and self-reliance has become blurred (Porter, Reference Porter1995). If the essence of an independence-defining activity is in the desirability and value of a task, rather than its contribution to day-to-day routine, then this may account for why the congruity between independence and ADLs is not as ineluctable as was once supposed.

The narrative generated through the interview with Margaret provides an exemplar of this point. Due to physical impairments, Margaret found it more difficult to take part in previous roles of participation and relied on her daughter for transport and support with some everyday activities. Even so, Margaret retained a sense of independence by having the freedom to wander the shops as she pleased on her mobility scooter:

So when my daughter goes to the shops, to the supermarket and stuff, she takes me, takes my scooter in the back of the car and I can go shopping and you know choose what I want from the shelves and I go wandering around the shop until I drive my daughter mad because she doesn't know where I am and I've put all sorts of things in my basket that I'm not supposed to have got. Anyway, it makes me feel independent. I'm with [my daughter] and I'm subject to her taking me there but when I'm there with my scooter I'm free. (Margaret, 84 years)

Margaret also spoke of the efforts that she made to maintain some independence in her own care and ADLs:

…there are things that I could do but I don't because [my daughter] does them but there are things that I could do if I really had to but I'd rather not because it's too much of a struggle. Like walking from the kitchen into the lounge, by the time I'm here on my chair my heart's beating like mad and it takes a lot out of me, well it takes a lot out of me just to get dressed but I will do it because I don't want to become totally useless. (Margaret, 84 years)

Though both tasks seem to contribute to Margaret's experience of independence, there is a marked difference between the language used to describe them. Whilst shopping was invigorating and helped Margaret to feel that she was ‘free’, getting dressed was a ‘struggle’ that really took it ‘out of’ her.

Rather than making her independent, getting dressed was an ADL that Margaret endured to avoid becoming ‘useless’ or dependent. Whether independence and the avoidance of dependence are synonymous is questioned by Secker et al. (Reference Secker, Hill, Villeneau and Parkman2003). Certainly the energising and stimulating portrayal of riding around on her mobility scooter that Margaret associated with independence seemed to speak to a quite different concept from that illustrated in her struggle to get dressed.

Participation, therefore, refers to a participant's ideal of independence as being involved in meaningful life situations. What counts as participation is not determined by what the activity is but how it is perceived and valued by the older person. For the participants of this study, participation was related to hobbies, social roles and community involvement. Significantly, the meaning of independence went beyond the ability to perform basic ADLs and focused on forms of activity that enriched the participant's experience by providing stimulation, social contact, or a way to distract or express themselves.

Although the difference was not clear-cut, there was a tendency for male participants to value ‘doing things’ outside the home and that were generally more physically intensive/demanding, compared with female participants whose participation preferences tended to be more socially or domestic oriented. These results resonate with several discourses on gendered identity, including masculine independence (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Braunack-Mayer, Wittert and Warin2007), traditional gendered roles (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Wolfe, Coughlan and Koehn1999) and gender differences in coping styles (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Cornman and Carr2014a).

Autonomy – ‘You … make the decisions’

Being able to make decisions and invoke agency in a situation was a defining feature that participants used when articulating their meanings of independence. Lucy shared how there were times when having the freedom to make decisions was liberating:

I've got independence because if I want to go, if I want to do anything you know you haven't got anybody to ask. (Lucy, 78 years)

Arthur also reported that not having ‘anybody telling him what to do’ was key to his understanding of independence:

I am fully independent as I said if I want to do anything, I don't have to sort of consider what anybody else would think about it … I just do it. (Arthur, 81 years)

Making and acting upon one's own decisions is an asset of autonomy (Collopy, Reference Collopy1988; Agich, Reference Agich2003; Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Pöder, Mamhidir, Nilsson, Kristofferzon and Häggström2015). Like with activity, autonomy and independence frequently co-habit studies in gerontological literature but the differentiation between them is rarely explicit. Sometimes the terms are presented as if they are interchangeable (Haak et al., Reference Haak, Fänge, Iwarsson and Ivanoff2007; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014), in other studies independence is one component of autonomy (Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Pöder, Mamhidir, Nilsson, Kristofferzon and Häggström2015) or vice versa (Gignac and Cott, Reference Gignac and Cott1998). Autonomy itself is often ill-defined, with the term being used to describe a wide range of possible value-laden ideas. In this study, autonomy is used to paraphrase the idea of being able to make and act on one's own decisions, and is separated from the related but distinct idea of control which we reserve for talking about autonomy in the context of receiving help.

As seen in the quotations above, participants referred to autonomy as a desired or aspirational concept but having to make your own decisions was not always a welcome attribute of independence. In some cases, the need to make one's own decisions was an obligation rather than a freedom, such as in the context of widowhood:

Well I, when I became independent I was made a widow nearly four years ago and … only kind of what you call had an independence … now in these past … the first … the first 18 months I didn't know whether I was coming or going and then now I feel that I'm, well, I am on my own you've got to learn to make your own decisions. (Lucy, 78 years)

Lucy's phrasing, ‘you've got to’, speaks to a rather different side of autonomy from that portrayed by Arthur, highlighting that whilst choice and autonomy can be liberating in some instances, it can also be associated with responsibility and burden.

Marital status had a notable effect on the contribution of autonomy to participants’ meanings of independence. They shared that being married and living with a spouse necessitated a certain amount of compromise and could hinder the experience of autonomy by exerting a form of moral and physical interdependence (Hsu and Barrett, Reference Hsu and Barrett2020). In some cases, marital status contributed to a discrepancy between how participants talked about their independence and how they scored it.

Tony stated in his meaning that, because of the support he received from his wife, he had never had to experience independence and therefore found it difficult to define what it meant. Despite this suggestion that independence was not familiar to him, when asked where he would mark himself on a scale of 1 to 10, he felt that he was fully independent:

Well I don't think I've really had to experience [independence] properly. I don't really know … You know as a child you are always dependent on parents and until such time as you then well, am I dependent on you? [asking wife in the same room]. Pretty well yes. (Tony, 80 years)

Bert also offered a different interpretation of independence when considering it from a married perspective. Marital status was not mentioned in Bert's explanation of what independence means to him, but due to a decrease in autonomy, it did effect how he scored his independence:

At the moment I am because I've got a wife, I can't be completely independent so, if you've got a wife then you've got to knock about three or four off straight away. So, I've got to do as I'm told as long as I'm here. (Bert, 78 years)

The differences in autonomy described by participants depending on their marital status are commensurate with the findings of Hsu and Barrett (Reference Hsu and Barrett2020) who identified that autonomy is often lower in married individuals but that other contributions of marriage to wellbeing appeared to counterbalance the need for autonomy. Combining these results with the understanding generated about the potential burden of obligatory independence (Allam, Reference Allam2015) incurred through widowhood makes an important challenge to the common assumption that autonomy is universally coveted.

Control – determining if and how help is received

Receiving help was a third common reference point for participants’ definitions of independence. The context and parameters of what it meant to receive help varied. Contrasting understandings of independence in which receiving help is perceived to be analogous with dependence, participants’ perspectives suggested an understanding that was less clear-cut. Participants reported strategies of normalising, reciprocating or reframing help received which aligned with notions of interdependence (Fine and Glendinning, Reference Fine and Glendinning2005; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014) and enabled them to retain an independent identity (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Vegeris, Hudson, Barnes and Taylor2004). Whilst interdependence suggests a passivity to the acceptance of mutual benefit in helping relationships, we chose the concept ‘control’ to better capture the essence of participants' attitudes towards help and independence which suggested a much more active negotiation of what level of help was personally acceptable. Often, receipt of help could be justified if the participant had control over what and how help was delivered.

A desire to avoid receiving help was deeply ingrained for many participants. For example, Jean and Nancy talked about their avoidance of asking for help as an effort to uphold the value of being able to do tasks for oneself that had been instilled in their upbringing:

…some people might grow into it but I think well I think for me personally it's the way I was brought up you know I was brought up to be independent. (Jean, 79 years)

I think it's [the desire to do for oneself] in me and I think it's a Yorkshire … When I say it's a Yorkshire thing my background if you know what I mean but that might sound a bit abrupt but yeah, you know I just get on with it. I think that's a very working class maybe a very working-class thing and that's where I come from a working-class background. (Nancy, 82 years)

However, though perceived as a threat, receiving help did not automatically result in dependence. Instead, the level of threat to independence incurred by receiving help varied depending on the context, with participants’ level of control over the help often determined by their perception of their ability to reciprocate (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Vegeris, Hudson, Barnes and Taylor2004; Dunér and Nordström, Reference Dunér and Nordström2005). For example, as Jean's comments above illustrate, not having help was key to defining her understanding of independence but her later comments revealed that the association depended on the contextual factor of whether or not that help was paid for. She believed that the older neighbours that she had cared for voluntarily would have thought themselves dependent as they did not pay Jean for her help. On the other hand, Jean felt that her own receipt of help, from the milkman, would not be seen as dependence as it was a paid-for service and one that sat within accepted societal ‘norms’.

The regulations of lockdown meant that several participants had felt forced to accept help for the first time and spoke about the changes they had made to organise the support and prevent it from undermining their independence. Rose, having had a career helping others for most of her life, found the idea of accepting help very difficult. To retain a sense of control, Rose took steps to reduce the amount of ‘burden’ she felt that she was imposing on her neighbour:

I don't want them to [get my shopping], I don't want to be a burden I would look at it as a burden to them I mean the girl across the road … she was getting my repeat prescriptions from Tesco but I would always say to her no, just do it when you go shopping but she never would she'd go straight and get it but now well this time I took the car up the road and went and got it myself … I suppose she did it with the best of intentions but I always ordered it well ahead so that she'd got plenty of leeway she didn't have to rush. (Rose, 84 years)

Even though doing tasks for herself was a key principle of Rose's understanding of independence, she was willing to accept some loss of self-reliance provided that she could retain some control over the situation and reduce the impact on others. When Rose's plans were thwarted by her neighbour, the perceived threat to her independence became too much and Rose found a different way to manage.

Not all participants showed a similar level of concern about receiving help. Monica acknowledged that she received help with cleaning and gardening (a paid-for service), but stated confidently that this did not undermine her independence because the help was not for her but was for possessions that she had:

I certainly wouldn't want to do the garden but I mean that's just the luck of the draw whether you've got a big garden or a little one and I've never really liked it so, I was very pleased to have her and I don't count that as my independence because that's not me that's house or garden or surroundings. (Monica, 83 years)

As well as reciprocating the help she receives through financial payment, Monica further distances herself from the threat of receiving help by conceptually adjusting what it means to receive help to fit with her own narrative rather than either the expectations of society or of gerontological theory (Katz, Reference Katz2000).

Bert and Arthur were also comfortable with accepting some forms of help. In Bert's own wording, both men appeared to accept help as ‘tit for tat’, seeing it as a normal part of social interaction. Any potential threat to independence seemed to be countered by the fact that the men felt confident that they could, and probably had, repaid the favour previously:

I receive it [help] with thanks yes but most of my help is on technical things … If I need help … I've got help because I help other people. So, it's tit for tat is some of it. (Bert, 78 years)

And we [cycling group] all know that if we do need any help with anything, we can always ask somebody and we will get the help … Because we have various plumbers and joiners in our group … They're all retired now but you know if you want to do anything. (Arthur, 81 years)

Despite the apparent acceptance of help in the examples of Monica, Bert and Arthur, a need for control in the helping relationship persists. For Monica, this control appears in her ability to separate herself from the objects requiring help. Bert and Arthur retain control by having confidence that they could return the help if needed. It is difficult to say whether these participants’ ambivalence to help would be different in different circumstances. However, it is not unthinkable that they would find it more difficult to accept help should the circumstances be different, e.g. the help was for Monica herself or Bert and Arthur were no longer physically able to return the help given. Notably, the ability to normalise help was more prominent in the narratives of male participants. Tony and Bert referred to domestic tasks such as cooking and cleaning as part of their spouse's role rather than their own. Since these tasks were not part of their duties, benefiting from someone else doing them was not perceived as a threat to independence but as part of the unspoken social contract of the marital relationship and concurs with the findings of Clarke and Bennett (Reference Clarke and Bennett2012) which suggest that women are more likely to see tasks of self-care as a moral responsibility.

Theme 2: It's not what you have, but how you think about it that creates independence

The second theme, ‘It's not what you have, but how you think about it that creates independence’, can be simplified to a phrase used by participants of ‘mind over matter’. It encompasses the finding that psychological rather than physical qualities were most consistently described when participants talked about the factors that helped them to achieve and maintain independence. Though environmental factors such as equipment and accommodation were discussed, participants’ ideas about their importance were divided. For instance, William and Tony had opposing views about the use of walking aids. William, at 98 years old, was strongly against the idea of using a walking stick when outdoors. Though it had meant giving up some of his former activities, such as walking across the road to the cricket ground, he perceived the loss as more acceptable and less threatening to his independence than ‘advertising’ his age by using a stick:

I'm not allowed to go out on my own because I fall and I don't use a, I didn't want to advertise my age by using a walking stick … I'm very proud that way. (William, 98 years)

Tony, at 80 years, saw things differently saying, ‘Oh, if it became necessary no problem yeah. I mean when I've done my back a couple of times … I've had to use sticks and things.’ For Tony it seemed that the value of being able to continue his activities was more important for his sense of independence and enabled him to accept the walking aid as a means to achieve it.

When considering potential constraints on independence, Jean thought that housing and being in a flat was a key consideration because of decreased accessibility should mobility decrease:

Well, as I say if you live somewhere where it's difficult to get out and about you would become dependent much, much sooner … than somebody who could get out because it would be so much harder. Just simply to get out of the house or where you're living … Because you would then more or less become dependent well you would depend on someone to get your shopping for you for instance … You'd be more dependent wouldn't you on the simple things, everyday things. (Jean, 79 years)

Rose also felt that living in a bungalow set her up well for ageing as it had been helpful in maintaining the independence of her mother-in-law in previous years. In contrast, Tony and his wife felt confident that they could ‘just move’ from their top-floor flat should the need arise and drew on previous experience of recent moves to justify their confidence. Monica also saw living in a house with stairs as a benefit to her independence as she used the stairs as a regular form of movement and exercise to help her remain strong:

Sure, I mean even just to move, I mean even putting washing out on the line is stretching and going up and down the stairs, I make sure that I go up and down the stairs every time that I want to go to the toilet rather than using the downstairs toilet you know that type of thing. (Monica, 83 years)

As seen in the examples above, the differences in participants’ views on the importance of different environmental factors for independence depended on the individual's values and approach to life rather than the presence or absence of the factors themselves. Supporting the idea that independence is more than simply the presence or absence of environmental factors, participants talked about the effort that they actively applied to maintain their independence:

I think I am quite an independent person because I don't like to rely or put too much pressure on other people, I like to do things myself. I just work through it and do things. (Rose, 84 years)

I contrast that with the effort that goes into all of the things I choose to do you know all of those things that I've listed to you that's what keeps me independent. (Henry, 77 years)

Participants referred to the importance of psychological qualities resembling attitude, self-efficacy and resilience in providing the drive and activation to push themselves and keep going even when it felt easier to just ‘give up’.

I think your health and your mental attitude. Those are the two main things. I think some people, if you had two people, two different people with the same capacity one could be dependent and the other couldn't be because they wouldn't feel they were, they couldn't feel they could do it or they wouldn't do it. (Jean, 79 years)

Curiosity and eagerness to learn were also key psychological factors that had a promoting function in the maintenance of independence:

Interviewer: And what is it about learning that you think is so related to independence?

Respondent: It's making, it's your brain is working. (Joy, 76 years)

As well as helping the participants to move towards their goal of independence, some psychological qualities, such as resilience and, within it, self-efficacy, appeared important to participants’ ability to avoid negative occurrences that could detriment their ability to be independent. For instance, Monica believed that people were likely to treat her differently if she looked older and, therefore, she valued her dark hair:

Interviewer: Several times you mentioned about looking older and … about how people would respond to you if you looked older and I wondered … how that affects your independence…

Respondent: Well actually it's quite nice at times because if I go into a restaurant or café they will carry my drink to the table for me … because my walking is so juddery that I can't always hold my cup still … I do ask now because rather than have an accident with the cup and maybe drop it or panic it's easier if someone does that for me and I realise that they are quite willing to do it and that suits me … but I don't count that particularly as losing my independence because I like to go in and sit down and be waited on. (Monica, 83 years)

Monica explained that looking older can make people change their behaviour towards her, such as carrying her drinks, which could be perceived as preventing her from making her own decisions by assuming that she is not capable of doing the task herself. However, Monica reframes the situation to one of more, rather than less, choice and takes ownership of the decision to ask staff to carry the drinks. By thinking more flexibly about what it means to be independent, rather than confining her understanding to the dichotomy of ability or disability (Reference Freedman, Cornman and CarrFreedman et al., Reference Freedman, Kasper, Spillman, Agree, Mor, Wallace and Wolf2014b), Monica preserves her sense of independence.

Discussion

Using rigorous analytical methods to generate an understanding of independence from the perspectives of older people, we determined that the concepts autonomy, control and participation are defining features of independence which were shared within participants’ understandings of independence. The value that participants applied to each of the three concepts varied depending on their personal beliefs and experience, resulting in unique personal interpretations of independence. Resources of the mind, such as resilience, confidence and optimism, rather than observable or material assets, were the facilitators of independence that we generated from our analysis of the perspectives of older people participating in this study.

The multipartite and amorphous definition of independence is consistent with existing research that highlights the multi-dimensionality of independence (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Vegeris, Hudson, Barnes and Taylor2004; Hammarström and Torres, Reference Hammarström and Torres2010). Beyond naming the concepts that construct independence, we have shown how each shares attributes of, but is not entirely captured by, existing theories. The results concur with assertions that independence is an active pursuit (Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Pöder, Mamhidir, Nilsson, Kristofferzon and Häggström2015; Narushima and Kawabata, Reference Narushima and Kawabata2020), and are commensurate with activity theory (Knapp, Reference Knapp1977), ‘doing things’ contributed significantly to the sense of joy and wellbeing that participants associated with independence. Critically reflecting on what ‘doing things’ meant for the participants of this study showed that the value of an activity for independence was determined less by the physical effort involved or the social engagement engendered by it, but by the meaning and purpose a participant could generate from it. Contemplative activities and pursuit of everyday interests were key to independence and appeared to trump other forms of activity such as physical movement or social engagement (Katz, Reference Katz2000) in participants’ descriptions of what it meant to have independence. Using the ICF concept of participation, rather than activity, to capture this distinction, we refined the understanding of the relationship of activity to independence.

The importance of the concepts autonomy and control to independence are also coherent with existing theory within the literature on disability (Gignac and Cott, Reference Gignac and Cott1998; Dunér and Nordström, Reference Dunér and Nordström2005) and interdependence (Fine and Glendinning, Reference Fine and Glendinning2005), respectively. However, whilst the terms are often used interchangeably, we separate them to show the distinct contribution of each. Importantly, we challenge existing research (Åberg et al., Reference Åberg, Sidenvall, Hepworth, O'Reilly and Lithell2005; Dunér and Nordström, Reference Dunér and Nordström2005), which suggests that the value of autonomous decision making is triggered only by a decline in physical health or ability to remain self-reliant. In this study, autonomy was valued by some of the fittest and most isolated participants, suggesting that its importance predates loss of these vital resources. The concept of control focused on attitudes specifically in the context of receiving help, reinforcing assertions that independence is not solely reserved for those who exhibit the extreme end of self-reliance (Breheny and Stephens, Reference Breheny and Stephens2012; Narushima and Kawabata, Reference Narushima and Kawabata2020). However, an inherent interdependence was not passively accepted by participants but actively negotiated, providing a sense of control that supported personal representations of independence.

The idea that the facilitation of independence relies on more than a narrow scope of physical abilities is consistent with existing literature that have shown ADL assessments to be blunted by a lack of consideration of psychosocial influences (Plath, Reference Plath2008; Ravensbergen et al., Reference Ravensbergen, Timmer, Gussekloo, Blom, van Eijk, Achterberg, Evers, van Dijk and Drewes2022) or individual adaptation (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Kasper, Spillman, Agree, Mor, Wallace and Wolf2014b). Captured in the concept ‘mind over matter’, we demonstrated that participants perceived their mental attitude to be the strongest determining factor to their experience of independence. Although the importance of individual values may seem self-evident in a context of an increasing move towards person-centred care, these values are not recognised in the tools and policies created to assess and promote independence. Observable functions such as ADL and extended ADL measures (Katz, Reference Katz2000; Tewell et al., Reference Tewell, O'Sullivan, Maiden, Lockerbie and Stumpf2019), ability to live alone (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Nancarrow, Parker, Phelps and Regen2005) and receipt of care (Barken, Reference Barken2019; Hammarström and Torres, Reference Hammarström and Torres2010) are used to assess and evidence independence at critical junctures, such as when determining the person's destination following discharge from hospital, or when determining their eligibility for equipment or other forms of support. Neglecting wider psychosocial factors, particularly attitude, self-efficacy, resilience and personal beliefs that were described as so important to the older participants in this study means that such decisions are made with only part of the picture, and support to improve those outcomes only addresses part of what it means to be independent. The concept of ‘mind over matter’ epitomises the pivotal role played by psychological qualities of personality play in determining whether independence is experienced irrespective of the availability of physiological or material resources and is cognisant with Havighurst's (Reference Havighurst1968) results which also showed personality to be central to older people's experiences and preferences of ageing. Our results reinforce the need for more innovative approaches to outcome measures and that ADL assessment alone is insufficient for understanding the true scope of independence (Ravensbergen et al., Reference Ravensbergen, Timmer, Gussekloo, Blom, van Eijk, Achterberg, Evers, van Dijk and Drewes2022).

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study was that it sought, and was designed to, conceptualise independence from the perspectives of older people. Participants were purposefully sampled from two distinct regions of England and with varying demographic characteristics of sex, living status, age and rural/urban setting. A diverse range of participant perspectives added to the richness of information generated and gave insight into how variation within themes occurred across different contexts. However, some limitations in the characteristics and size of the sample have the potential to limit the transferability of the results to older people who do not share the same traits or access to resources. Difficulties recruiting participants who were aged 90+, living with family or who perceived themselves to be too unwell to take part created some limitation to the diversity of the sample. Participants’ propensity to focus their answers towards internal facilitators of independence (i.e. attitude, self-efficacy and personal values) may be explained by a relative wealth of additional resources, such as physical health and financial stability, that many members of the wider population of older people would not be able to take for granted. Although socio-economic data were not available to be used as part of the sampling strategy, our recruitment of participants from more than one region increased the likelihood of variation in relative affluence. References in interviews also suggested some variation in socio-economic background, suggesting that ready access to independence-supporting resources was not universal among participants and therefore challenging the idea of relative resource abundance as the sole explanatory factor. Although our results show some differences in the understanding of independence depending on a participant's marital status or gender, a differential impact of age and rural/urban context was not discerned from the data.

It is important to note that, although through this study we aimed to understand and prioritise older people's perspectives, we also recognise that it would be naïve to suggest that these views were completely separate and isolated from influence from their social context. The ‘busy ethic’ (Katz, Reference Katz2000) and the ideals of healthism (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Frost and Britten2015) and self-sufficiency continue to be valorised and coveted in Western culture, and are likely to have shaped the participants’ propensity to name personal attributes over external supports as the most important contributors to their independence. Policy frameworks promoting self-management and personal control have simultaneously shifted the onus of health and wellness away from the state and on to the individual, reframing social ideals to make care of the self a moral responsibility of the individual (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Frost and Britten2015). Whilst acknowledging the potential benefit of personal responsibility, such as maintaining control and continuing to participate in meaningful roles, which may have led to the prominence of personal action in participants’ responses, it may also be that participants’ responses have been shaped, consciously or not, by the flows of social discourse. The ability to maintain a personal value – and identity – system which contrasts overwhelming societal influence would be a useful area of future study.

Conducted during the lockdown imposed by government legislation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the study design required several adaptations. Interviews, originally planned to take place face-to-face, were conducted online or by telephone. Using digital methods instead of face-to-face interviewing, on the one hand, was a limitation to the study because these methods may be less inclusive for people who have hearing or sight impairments and/or who are unused to working with technology and the potential advantages it can bring. Further, interviews from a distance limited the understanding that could be gathered about participants’ personal contexts, since the researchers were not able to visit participants’ homes and obtain first-hand experience of their living set-up (Irvine, Reference Irvine2011). As such, it was not possible to compare or verify participants’ perceptions of themselves with how they may be perceived from an external perspective (Luong et al., Reference Luong, Charles, Rook, Reynolds and Gatz2015). On the other hand, some participants considered the digital format as more convenient than having someone come to their home and valued the flexibility that that entailed. In addition, the reduced ‘pressure of presence’ (Weller, Reference Weller2017) of non-face-to-face interviews may have enabled the older participants to speak more openly about experiences of dependence, which is often associated with shame or judgement, because the distance imposed by this format provided a sense of safety.

Implications for policy and practice

Recognising the multifaceted nature of independence and understanding the nuance of its multiplicity is essential for designing policy and services that facilitate this key proponent of ageing ‘well’ in an effective and meaningful way. By introducing an increased level of precision to understanding the facets of independence and what they mean to older people, we provide important insight for the tailoring and delivery of person-centred care. We must move away from trying to define independence by any one of these concepts and consider how interactions between them are individually configured and navigated.

Conclusion

Independence, for older people, is as much a state of being as it is a goal or ambition. Whilst gradual decline in independence may be accepted and adapted to over time, sudden changes in independence, most likely to be those encountered in practice, may be more difficult to accommodate. In such situations, standardised support to obtain a standardised level of independence is unlikely to be sufficient. Understanding how older people have developed and honed their own meaning of independence and the intrinsic and extrinsic assets they have drawn on to embody that interpretation, is essential for a return to a level of independence that is meaningful and sustainable for that individual.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X23000740.

Acknowledgements

The data for this study were made available through Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. CARE75+ is led by the Academic Unit for Ageing and Stroke Research, University of Leeds, based at the Bradford Institute for Health Research, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The funding for CARE75+ is provided by the Yorkshire and Humber Applied Research Collaborations. The authors would like to thank all the participants and PPIE group members who gave their time to be involved in this study. Thank you to colleagues Kitty Parker and Kate Allen who constructively reviewed the article. Versions of the paper have been presented at the 2021 South West Academic Primary Care conference and the 2021 British Geriatric Society Annual Conference.

Author contributions

ET: conceptualisation; methodology; investigation (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing – lead author. JF: conceptualisation; methodology; formal analysis (supporting); writing – reviewing and editing; supervision. VG: conceptualisation; formal analysis (supporting); writing – reviewing and editing; supervision (lead supervisor). SB: conceptualisation; writing – reviewing and editing; supervision. AC: conceptualisation; writing – reviewing and editing; supervision. LB: enabled and supported the contact with and recruitment of interview participants from the CARE75+ study; writing – reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the paper.

Financial support

Thie work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration South West Peninsula. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted for this study by the University of Exeter Medical School Research Ethics Committee (RG/CB/20/03/243). The CARE75+ study was approved by the NRES Committee Yorkshire and Humber–Bradford Leeds, 10 October 2014 (14/YH/1120) (Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Brown, Young, Teale, Hawkins, Spilsbury, Mountain, Young, Goodwin, Hanratty, Chew-Graham, Brundle, Mahmood, Jacob, Daffu-O'Reilly and Clegg2019).