No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2017

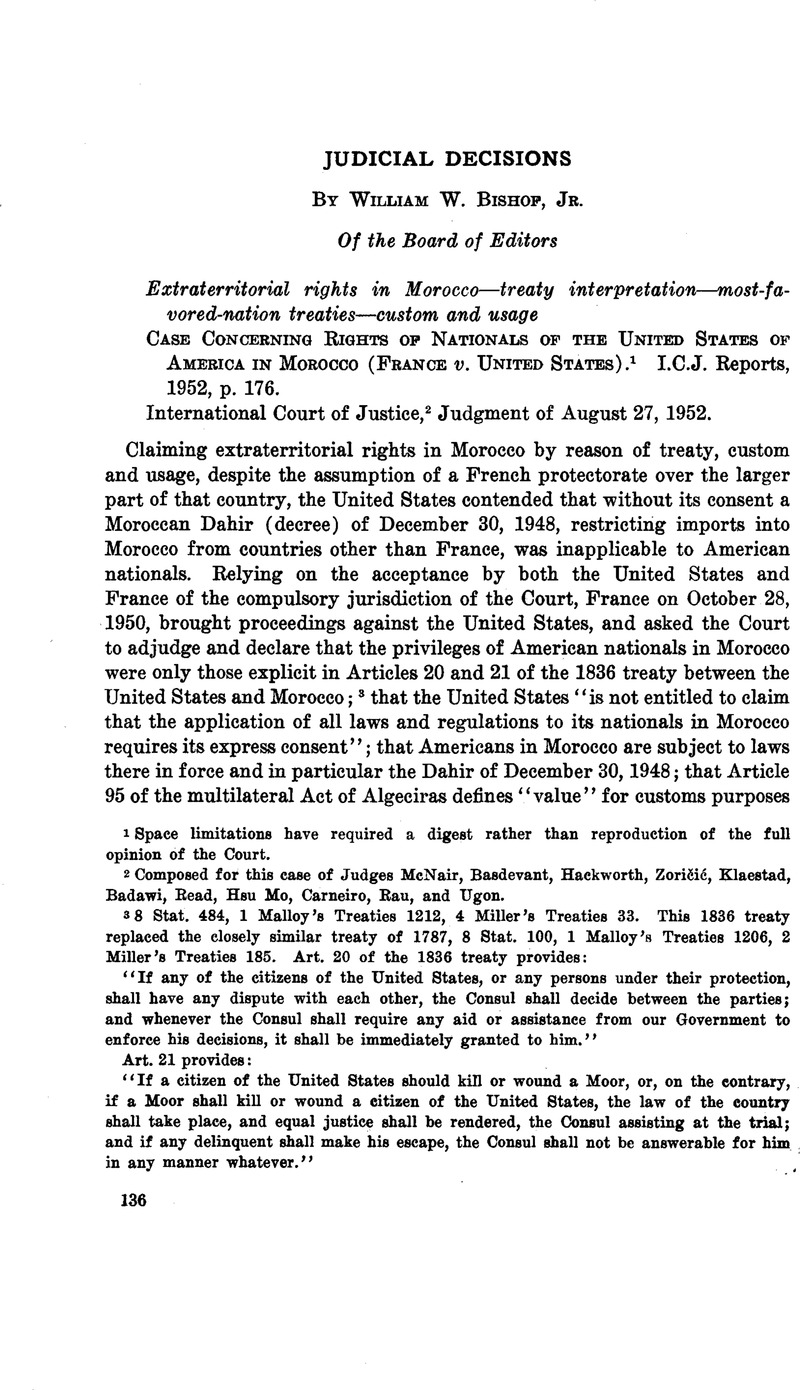

1 Space limitations have required a digest rather than reproduction of the full opinion of the Court.

2 Composed for this case of Judges McNair, Basdevant, Hackworth, Zoriěić, Klaestad, Badawi, Read, Hsu Mo, Carneiro, Rau, and Ugon.

3 8 Stat. 484, 1 Malloy’s Treaties 1212, 4 Miller’s Treaties 33. This 1836 treaty replaced the closely similar treaty of 1787, 8 Stat. 100, 1 Malloy’s Treaties 1206, 2 Miller’s Treaties 185. Art. 20 of the 1836 treaty provides:

“If any of the citizens of the United States, or any persons under their protection, shall have any dispute with each other, the Consul shall decide between the parties; and whenever the Consul shall require any aid or assistance from our Government to enforce his decisions, it shall be immediately granted to him.”

Art. 21 provides:

“If a citizen of the United States should kill or wound a Moor, or, on the contrary, if a Moor shall kill or wound a citizen of the United States, the law of the country shall take place, and equal justice shall be rendered, the Consul assisting at the trial; and if any delinquent shall make his escape, the Consul shall not be answerable for him in any manner whatever.”

4 Art. 95 of the Act of Algeciras signed April 7, 1906 (34 Stat. 2905, 2 Malloy’s Treaties 2157, this Journal, Supp., Vol. 1 (1907), p. 47, at p. 70), provides:

“The import and export duties shall be paid cash at the custom-house where liquidation has been made. The ad valorem duties shall be liquidated according to the cash wholesale value of the merchandise delivered in the custom-house and free from customs duties and storage dues. Damages to the merchandise, if any, shall be taken into account in appraising the depreciation thereby caused. Merchandise can only be removed after the payment of customs duties and storage.”

5 For citations, see note 4 supra.

6 The Court specified: “It is common ground between the arties that the present dispute is limited to the French Zone of Morocco. & The Court cannot, therefore, pronounce upon the legal situation in other parts of Morocco.”

7 See this Journal, Supp., Vol. 6 (1912), p. 207. Regarding the establishment of the French Protectorate, see 1 Hackworth’s Digest of International Law (1940) 85 et seq.; 2 ibid. 504 et seq.; N. D. Harris, “ The New Moroccan Protectorate,” this Journal, Vol. 7 (1913), p. 245.

8 Judge Hsu Ho dissented on this point, appending a short statement of his view that “the United States is not entitled to exercise consular jurisdiction in cases involving the application to United States citizens of those provisions of the Act of Algeciras … which, for their enforcement, carried certain sanctions.”

9 The Madrid Convention, 22 Stat. 817, 1 Malloy’s Treaties 1220, deals with the right of protection of Moroccan nationals by foreign governmental representatives, businessmen, etc. Art. 17 stipulates that “The right to the treatment of the most favored nation is recognized by Morocco as belonging to all the Powers represented at the Madrid conference.” See also this Jouenal, Supp., Vol. 6 (1912), p. 18.

10 Here the Court quoted its opinion in the Asylum Case, I.C.J. Reports, 1950, p. 266, at 276–277, this Journal, Vol. 45 (1951), p. 179, at p. 184:

“The Party which relies on a custom of this kind must prove that this custom is established in such a manner that it has become binding on the other Party. The Colombian Government must prove that the rule invoked by it is in accordance with a constant and uniform usage practised by the States in question, and that this usage is the expression of a right appertaining to the State granting asylum and a duty incumbent on the territorial State. This follows from Article 38 of the Statute of the Court, which refers to international custom “as evidence of a general practice accepted as law’.”

11 Although the Court rejected the general American submission relating to tax exemptions by a vote of 6 to 5, it rejected by a 7-to-4 vote the specific submissions relating to the consumption taxes.

12 Judges Hackworth, Badawl, Carneiro and Sir Benegal Rau rendered a joint dissenting opinion regarding the conclusions of the Court on the broader consular jurisdiction (found to rest on long-established custom and usage, “which is only another name for agreement by conduct, [which] can only be terminated in the way in which international agreements can be terminated”; as well as on “necessary implication” from the Act of Algeciras and the Madrid Convention); on fiscal immunity (by “necessary implication” from the Act of Algeciras and the Madrid Convention, which permitted the levying only of narrowly delimited taxes, as well as from the bilateral treaties and the most-favored-nation clause); and on Art. 95 of the Act of Algeciras, which they found to mean that “the only value to be taken account of is the value in the country of origin plus expenses incident to transportation to the customs-house in Morocco.”