No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

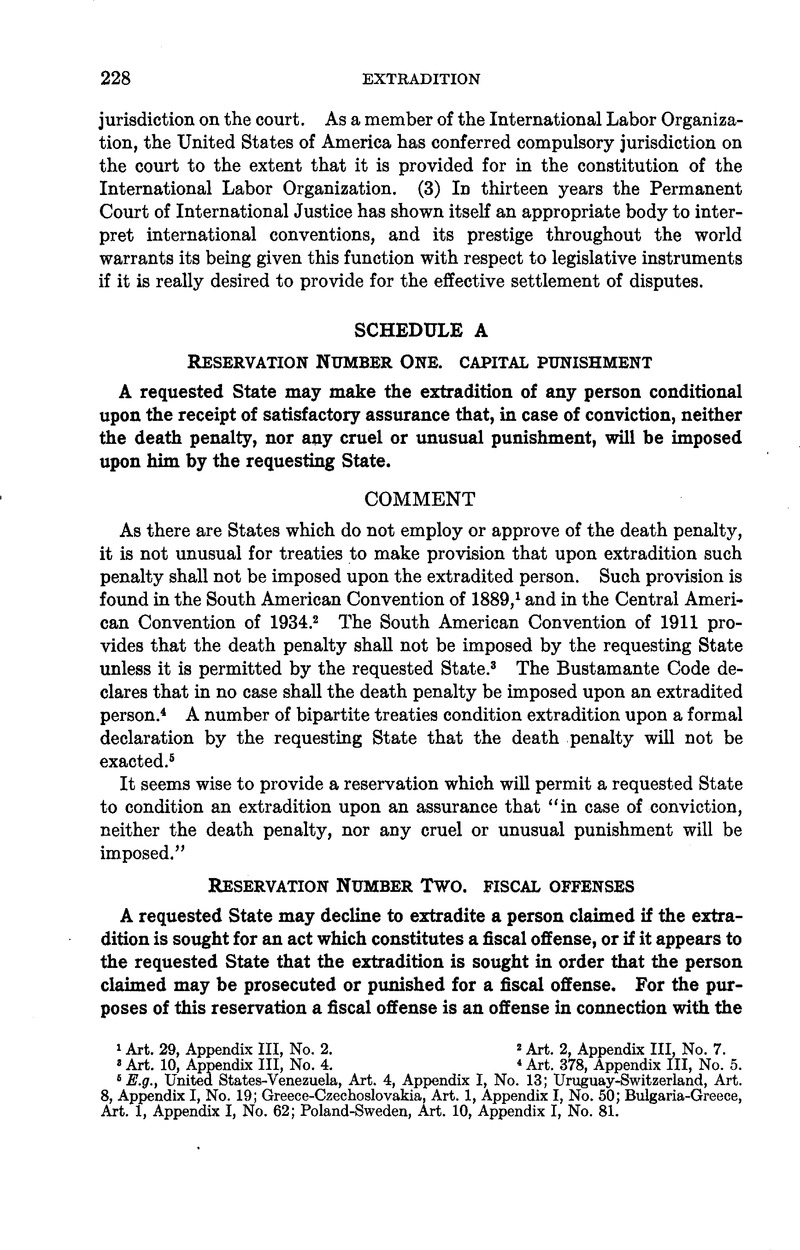

page 228 note 1 Art. 29, Appendix III, No. 2.

page 228 note 2 Art. 2, Appendix III, No. 7.

page 228 note 3 Art. 10, Appendix III, No. 4.

page 228 note 4 Art. 378, Appendix III, No. 5.

page 228 note 5 E.g., United States-Venezuela, Art. 4, Appendix I, No. 13; Uruguay-Switzerland, Art. 8, Appendix I, No. 19; Greece-Czechoslovakia, Art. 1, Appendix I, No. 50; Bulgaria-Greece, Art. 1, Appendix I, No. 62; Poland-Sweden, Art. 10, Appendix I, No. 81.

page 229 note 1 L’Extradition et le Droit Extraditionnel (1913), I, 16. See also Billot, Traité de l’Extradition (1874), 43.

page 229 note 2 Dorian v. Walter (1909), 132 Kentucky Reports, 54.

page 229 note 3 Droit Pénal International (1922), IV, §2128.

page 229 note 4 “L’extradition ne sera pas accordée pour les infractions aux lois fiscales, ni pour les delicts purement militaires.” Appendix VI, No. 13.

page 229 note 5 “L’extradition ne sera pas accorded: … 3—Pour les infractions aux lois de douane, d’imposts et autres lois financieres.” Propositions de M. Pella, Rapporteur Général.

page 229 note 6 “L’extradition serait exclude: … b) pour les infractions aux lois fiscales.” Resolutions adopted by the Section on Extradition, International Congress of Comparative Law, The Hague, August, 1932.

page 230 note 1 Sack, “(Non-) Enforcement of Foreign Revenue Laws, in International Law and Practice,” 81 University of Pennsylvania Law Review (1933), 559–560.

page 230 note 2 The author also quotes Abbott, C. J., as having said 11 years earlier: “It has been settled or at least considered ever since the time of Lord Hardwicke, that in a British court we cannot take notice of the revenue laws of a foreign state.” Id.

page 230 note 3 (1775, Kings Bench), 1 Cowper 341; 98 English Reports 1120. See also Planche v. Fletcher (1779, Kings Bench), 1 Douglas 251; 99 English Reports 164.

page 230 note 4 “A contract is, in general, invalid in so far as … the contract forms part of a transaction which is unlawful by the law of the country where the transaction is to take place.” Dicey, Conflict of Laws (1927, 4th ed.), p. 618.

page 230 note 5 Planche v. Fletcher (1779, Kings Bench), 1 Douglas 251; 99 English Reports 164.

page 230 note 6 42 Mississippi Reports, 444.

page 230 note 7 “The great majority of cases in France also validates these foreign contraband contracts.” Sack, op. cit., 564.

page 230 note 8 Cours de Cassation, 28 mars 1928, 56 Journal du Droit International (1929), 333

page 230 note 9 Foster v. Driscoll, [1929] 1 Kings Bench Reports, 470. See also Ralli Bros. v. Compania Naviera Sato y Azner, [1920] 2 Kings Bench Reports, 287.

page 231 note 1 “But the decisions just noticed, validating contracts whose incidental effect is to evade foreign revenue laws, are condemned by the high authority of Pothier, of Judge Story, of Chancellor Kent, of Mr. Chitty, of Mr. Westlake, of Mohl and of Bar.” Wharton’s Conflict of Laws (3rd ed., 1905), 1139. “If our law be justifiable in protecting these transgressions, it can be only on the plea of necessity. But where is the necessity? Shall we be told, that it is impossible to ascertain in the English courts the complex provisions of another country’s revenue law? … It may be true, that the rule of our law was adopted by way of retaliation for the illiberal conduct of other states and is continued from a cautious policy. But a cautious policy in a great State is but too often a narrow policy; and after all, the best policy for a State, as well as for an individual, will perhaps be found in honesty and honorable conduct. Indeed the system is so directly opposite to the clear principles of right feeling between man and man, that nothing could have withheld the States of Europe from concurring for its total abrogation, except the smallness of the gain or loss, that attends upon it.” 1 Chitty on Commerce and Manufacture, 83–84. See also Marshall, Insurance, I, 59–61; Westlake, Private International Law (7th ed., 1925), 305; Story, Conflict of Laws (6th ed., 1865), 316; Pollock, Contracts (9th ed.), 391.

page 231 note 2 Sack, op. cit, 564

page 231 note 3 “Les opérations de contrabande à l’étranger ne tombent pas sous l’application des lois répressives françhises, mais elles n’en sont pas moins reprouvées par la conscience publique. Une société n’ayant pour objet des opérations de cette nature est frappé d’une nullité radicale et absolue, aussi bien que les sociétés ayant pour objet la contrabande en Prance.” Trib. Dunkerque, 27 novembre 1906, 35 Journal du Droit International (1908), 138.

page 231 note 4 “Si une charte-partie a pour objet l’execution ou le concourse à des opérations de contrebande professionelle dirigée contre un État avec lequel on entretient des rapports amicaux, elle est nulle suivant le sec. 138 B.G.B.

“Selon la jurisprudence du Tribunal d’Empire toute sanction juridique doit être refusée en vertu du §138 B.G.B. aux actes juridiques dont le caractere general determine en considération de leur contenu, motif et but, pris dans leur ensemble, apparaît tant au point de vue objectif qu’au point de vue subjectif, comme contraire aux bonnes mceurs. Relativament à la contrebande professionelle dirigée contre un État ami, il est exigé par la jurisprudence, pour que le §138 B.G.B. ler alinéa, soit applicable, que les contrats la concernant aient pour objet direct de l’executeur ou d’y apporter une aide.” Arrêt du 9 février 1926, Reichsgericht; 57 Journal du Droit International (1930), 430.

page 231 note 5 “Le contrat conclu par le propriétaire d’une merchandise avec un commissionnaire-expéiteur dans le but de se procurer une fausse preuve d’une origine française de la merchandise, en vérité allemande, et de l’introduire par ce moyen frauduleux en Pologne malgré la guerre douanière germano-polonaise, est contraire aux bonnes mceurs et done annulable pour cause illicite.” Cour Supreme Vienne, 3 mars 1931, 58 Journal du Droit International (1931), 1180.

page 231 note 6 “Attendu … que la contrebande ne viole pas seulement les lois fiscales étrangéres, mais les notions de droit et de justice qui doivent dominer les relations internationales; qu’elle pervertit la loyauté commerciale et est un acte de concurrence malhonnête, même vis-è-vis des nationaux qui, plus scrupuleux, n’importent leurs merchandises dans les pays voisins qu’en acquittant les droits d’entrée.” Decision of the Court of Appeals of Bruxelles, Feb. 17, 1886, cited in Hindenburg.

Vide “Des Contrats conclus par Correspondance,” 29 Revue de Droit International et de Legislation Comparte (1897), 263, at 277.

page 232 note 1 “It should be pointed out that the non inclusion of fiscal offenses in extradition treaties in the 19th century can be explained also because at the time the general tendency was to extradite only for ‘grand crimes’, i.e. crimes of such a nature that offended the universal and most elemental notions of morality like murder, rape, arson, etc. Offenses of a violent character against the person were the first included. Afterwards offenses against property, and offenses which were committed without violence were included in the extraditable list. The complexities of modern commercial life and the new requirements of social security have demanded that offenses which are not personal or violent be made extraditable. John Bassett Moore, writing a long time ago, said: ‘There has been a general disposition on the part of the United States to include in extradition treaties crimes of violence and to exclude crimes of fraud…. In the refusal to include in its treaties of extradition crimes of fraud, the government of the United States has failed to recognize the change which, in the development of civilization, has taken place in the relative importance of criminal offenses.‘” Moore, Extradition (1891), I, p. 111

page 232 note 2 IV, §2128.

page 232 note 3 The treaty between France and Spain of 1916, in regard to Morocco, provides: Art. 2— “A person arrested by virtue of decisions, sentences, requisitions of preventive justice of one of the zones in the other zone, will be surrendered to the agents of the authorities asking for the surrender, at the place of exchange, later to be specified, without charge.” This treaty does not limit the offenses for which extradition is possible, and therefore includes, according to Travers, fiscal offenses.

The treaty between France and China, in regard to Annam, does not seem to be reciprocal in that France will extradite Chinese from Annam only in cases in which they could be extradited from France proper, while China promises to extradite Frenchmen without any sort of limitation as to offences, thereby including fiscal offences. See Art. 17 of the Treaty.

Saint-Aubin, L’Extradition et le Droit Extraditionnel (1913), I, 387, tells of a French law of June 27,1866, not included in the text of the code of criminal instruction, which authorized the prosecution in France of special offences committed in foreign countries, among others certain fiscal offences. Art. 5, sec. 2 of the law says: “Any Frenchman, guilty of offences and contraventions in matters of forestry, fisheries, customs and indirect contributions, committed within the territory of one of the neighboring states, can be prosecuted and tried in France according to French law, if that State authorizes the prosecution of its citizens for the same offenses committed in France.”

He also refers (ibid., p. 391) to conventions between Spain and France, by which they agree that, when Frenchmen violate custom laws of Spain, or vice versa, within four leagues of the frontier, the accused shall be surrendered to his country (really extradited, although without formal procedure) in case of the first offense; for the second, he will be punished by the country whose revenue laws he violated.

page 233 note 1 Appendix IV, No. 6.

page 233 note 2 It is interesting to contrast penalty provisions of Canada and of the United States. Art. 593 of the United States Customs Laws (1922) punishes, generally, the smuggling or unlawful entry of merchandise of whatever nature into the United States by imprisonment not to exceed two years. Accordingly, smugglers of opium, coca leaves and other habitforming drugs, as well as smugglers of jewelry, could only be extradited to the United States, under such a provision as that in the above draft on the ground of the base motives of the offender.

By Art. 203 of the Canadian Customs Law, if the articles smuggled or illegally entered are of a value under $200, imprisonment will not exceed a year, but if the value is above $200, imprisonment will be extended up to seven years. The result of the difference of punishment of these offenders in Canada and the United States would be, under Article 8 of the “Model Draft,” that Canada could ask extradition for most offenses against her tariff laws, while the United States could not ask Canada to extradite the violators of her own laws.

Just the reverse situation is presented by the Income Tax laws of both countries: the United States punishes (Income Tax Law of 1928, 45 Stat, at Large, 835) wilful evaders of the Income Tax law with not to exceed five years imprisonment. Sec. 80 of Canada’s Income Tax law only provides for 6 months imprisonment to its violators.

After a careful survey of all the fiscal offenses defined and punished by the Internal Revenue Laws of the United States (about 200 in number) only the following are punishable by imprisonment up to five years:

§454. Evading or attempting to evade tax on wines—5 yrs.

§337. Failing to efface marks, stamps, etc., on emptying cask or package having uncancelled stamps—5 years.

§485. Removing, using, etc., alcohol withdrawn for denaturing, in violation of provisions relating thereto—5 years.

§705. Violations of provisions relating to sale, etc., of opium and coca leaves—5 years.

§725. Violations of prohibitions concerning opium—5 years.

§765. Manufacturer of tobacco failing to procure or post certificate—5 years.

§781. Affixing false stamp to tobacco and snuff, box, or re-using stamp—5 years.

§882. Manufacturer failing to give bond—5 years.

§1183. Fraudulent execution of documents required by internal revenue law.

§1188. Manufacturing boxes, barrels, etc., unlawfully stamped or marked.

§1267. Aiding, assisting or advising in preparation or presentation of false return, etc.

All other offenses under the revenue laws are penalized by fines, or by imprisonment for from 3 months to 3 years.

page 233 note 3 “Pour les délits fiscaux, qui généralement ne figurent pas dans les traités particuliers d’extradition, la Commission pénale et pénitentiaire internationale a songée à les comprendre dans son avant-projet de traits type (art. 8). II semble que ce soit avec raison. Un état, lesé dans ses intérêts pécuniaires, a le même droit qu’un particulier, pour que justice lui soit rendue. Les motifs de l’extradition se remontrent dans le bas. L’absence d’une répression d’imitation pour les autres fraudeurs; et I’exil n’est plus une sanction suffisante pour le déliquant lui-même.” Unification des règies relatives à l’extradition. Rapport presenté par M. I. A. Roux, p. 7.

page 234 note 1 “Le projet de la Commission Internationale P’nale et P’nitentiaire (art. 8) comprend les délits fiscaux, parmi les délits, pour lesquels l’extradition doit être accordée. Justement M. le Prof. Roux fait rémarquer que un État, lesé dans ses propres biens patrimoniaux a le même droit d’un particulier à que justice lui soit rendue. D’autre part, la non-punibilite’ encouragerait les fraudeurs de l’Etat a perpetrer de nouveaux delits a son prejudice; tandis que I’exil ne serait pas un chatiment sumsant non plus pour le delinquant, qui a reussi a echapper a la justice de son Pays.” Rapport de S. Exc. Ugo Aloise, Unification des regies relatives a l’extradition, p. 45

Fauchille, Traité de Droit International Public (1922), 1,1012, and Rolin, 16 Revue de Droit International, 159, have clearly shown that a fiscal offense is not in any way to be considered as a political offense, merely because it is committed directly against the State and not against a particular person. They distinguish, as is usually done in regard to our municipal corporations, the governmental and proprietary functions of the government. It is against the latter that such offenses are committed.

page 234 note 2 L’Entr’Aide Repressive Internationale (1928), 110–112.

page 234 note 3 Appendix III, No. 5.

page 234 note 4 Appendix IV, No. 3. In both cases, M. Travers infers such tendency from the failure to expressly place fiscal offenses on the non-extraditable list. “… par leur silence même sur les infractions fiscales, consacre une conception aussi large que la loi francaise du 10 mars 1927.”

It is of interest in this connection to note that almost unanimously the extradition laws of the different nations, while making express declaration that political, and in some cases military and religious offenses are not extraditable, do not include fiscal offenses in the exception. See Appendix VI.

page 234 note 5 Appendix III, No. 2.

page 234 note 6 Appendix III, No. 3.

page 234 note 7 Appendix III, No. 6.

page 234 note 8 Appendix III, No. 7.

page 234 note 9 Appendix IV, No. 1.

page 234 note 10 Appendix IV, No. 2.

page 234 note 11 Appendix III, No. 4.

page 234 note 12 Appendix IV, No. 5.

page 235 note 1 Note to Art. I, Appendix IV, No. 4.

page 235 note 2 League of Nations Official Journal, Vol. 10, p. 205

page 235 note 3 “The meeting, which is attended by the representatives of twenty-seven countries, notes that as regards their main principles, the model draft conventions prepared by the technical experts constitute a useful basis of discussion for the preparation of model texts, whose object shall be to prevent double taxation and tax evasion.” Ibid., p. 206

page 235 note 4 Ibid., p. 221.

page 235 note 5 16 League of Nations Treaty Series, p. 123

page 235 note 6 Ibid., Art. 17.

page 235 note 7 Treaty of Dec. 23, 1925.

page 236 note 1 See, for these treaties, Appendix I.

page 236 note 2 (References are to Appendix I): Rumania-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 36; Estonia-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 37; Latvia-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 38; Bulgaria-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 39; Greece-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 50; Spain-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 51; Portugal-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 52; Hungary-Yugoslavia, Art. 3 (II), (4), No. 61; Bulgaria-Greece, Art. 3(d), No. 62; Bulgaria-Spain, Art. 3(d), No. 73; Latvia-Spain, Art. 3(d), No. 74; Germany-Turkey, Art. 5(3), No. 75; Poland-Sweden, Art. 3(d), No. 81; Sweden-Czechoslovakia, Art. 4(d), No. 88; Denmark-Czechoslovakia, Art. 3(d), No. 89.

page 236 note 3 See Article 2.

page 236 note 4 See the situation in Prance before 1866, supra, comment to Article 7.

page 236 note 5 Moore, Extradition (1891), I, §122, pp. 153 and 154; Charlton v. Kelley (1913), 229 TJ. S. 447.

page 237 note 1 See Appendix III, No. 6.

page 237 note 2 See opinions in comment to Article 7, supra.

page 237 note 3 Bustamante Code of 1928, Art. 345, Appendix III, No. 5; Montevideo Convention of 1933, Art. 2, Appendix III, No. 6; Central American Convention of 1934, Art. 4, Appendix III, No. 7; Rio de Janeiro Draft of 1912, Art. 5, Appendix IV, No. 3; Model Draft of the International Penal and Prison Commission, Art. 17, Appendix IV, No. 6.

page 237 note 4 Art. 4, Appendix III, No. 7; also in the Draft of the International Penal and Prison Commission, Art. 17, Appendix IV, No. 6.

page 237 note 5 Travers, Droit Penal International (1922), V, §§2249 to 2256, pp. 41 to 48; Resolutions of Oxford (1880), Art. 7, Appendix IV, No. 2.

page 237 note 6 French Law of May 10, 1927, Art. 5, has the same provision. See Appendix VI, No. 7. Similar provisions are found in the laws of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, following the Russian Penal Code of 1914, Art. 852(3); of Ecuador, Extradition Law, Oct. 6, 1921, Art. 41; of Panama, Extradition Law, Nov. 22, 1930, Art. 5; of Peru, Extradition Law, Oct. 23, 1882, Art. 3. Mexico and Cuba provide that naturalization shall only bar extradition if the person claimed has been a citizen for two years. Mexican Law, May 19, 1897, Art. 10, §3.

page 237 note 7 Travers, “Les Effets Internationaux des Jugements Répressive,” Becueil des Cours, Académie de Droit Internationale, 1924, III, p. 415 ff.; Barbey, De L'Application Internationale de la Règle Non Bis in Idem en Matière Répressive (1930), p. 49.

page 238 note 1 Barbey, op. cit., pp. 97-126.

page 238 note 2 Ibid., pp. 83-96.

page 238 note 3 Ibid., pp. 89 and 90.

page 238 note 4 Ibid., p. 90.

page 238 note 5 See comment on Article 9 of this Convention.