Introduction

Weak state capacity is a root cause of many of the world’s development challenges. During the last two decades, however, most countries in the Global South have developed a handful of new national social programs that represent “pockets of effectiveness” (Evans Reference Evans1995, 251; Geddes Reference Geddes1990) in otherwise weak and incompetent systems of social protection. These isolated national government agencies employ capable bureaucrats who are committed to protecting human security and promoting social justice. This trend has produced an odd duality within states—extreme effectiveness in some government service programs juxtaposed with extreme ineffectiveness in many others.

One common explanation for why relatively few national government programs develop into capable bureaucracies is that building capacity requires combatting corruption. This rests on an underlying logic that bureaucrats in many developing countries are more motivated to maintain their own wealth and power than to use the power of the state to promote broader development goals (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; North Reference North1990). Therefore, anticorruption rules need to be instituted, particularly at higher levels of bureaucracy, where the public servants who design and implement national policy are far removed from the citizens who depend on their programs. Political reformers across the developing world have followed this logic by instituting new accountability rules in public sector bureaucracies and by creating government auditing agencies to enforce them (Casas-Zamora and Carter Reference Casas-Zamora and Carter2017, 1–9; Santiso Reference Santiso2006; Schedler, Diamond, and Plattner Reference Schedler1999, 1–9). A large body of scholarship on developing-world bureaucracies focuses on assessing the effectiveness of these initiatives in reducing corruption.

Yet the bureaucrats who have built the most capable bureaucracies tend to paint a different picture of accountability rules. As a former bureaucrat in Brazil’s agency that runs the famously successful Bolsa Família cash transfer program explained, “it was very important to [escape government accountability rules] because if we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have accomplished a third of what we did.”Footnote 1 Similarly, a former director of Brazil’s famous national AIDS program emphasized, “if we worked only within the government’s rules, we would be skating in circles.”Footnote 2

Why did these bureaucrats view accountability rules intended to combat corruption as preventing them from building capable government bureaucracies, and how did they escape these barriers? This article draws from the public-management literature on red tape to show how the mechanisms designed to combat corruption can in fact limit bureaucratic capacity. National-level accountability requirements often involve procurement regulations that tightly control how bureaucrats spend their budgets, such as by forcing them to seek many layers of government approval for each purchase. They also involve civil service reforms controlling how bureaucrats hire new colleagues, such as by forcing them to use entrance exam scores as their only selection mechanism. Initiatives such as these are designed to root out corruption by laying out detailed rules for public officials to follow and by empowering independent agencies to enforce them. Yet, as this article reveals, they can also limit bureaucratic capacity by imposing heavy compliance costs. The first contribution of this article is thus to explain the puzzle of why bureaucracies in developing countries that comply with accountability rules are often incapable of fulfilling core functions.

The second contribution of this article is to reveal a common way that public officials who face a trade-off between complying with accountability rules and building high-capacity bureaucracies have escaped accountability measures. Although public officials have adopted a range of escape strategies, I focus on one that has been widely used but understudied: outsourcing bureaucracies to nonstate organizations. Nonstate organizations are not subject to the same government regulations as bureaucracies are, and they tend to have more flexible and streamlined rules. National public officials, by subcontracting nonstate organizations to perform the work of bureaucracies, escape the reach of government accountability institutions and make themselves accountable instead to less demanding nonstate organizations. Paradoxically, this practice of outsourcing bureaucracy to avoid accountability rules may help explain pockets of effectiveness among government service programs in developing countries—creating what I call “shadow” state capacity.

As I discuss in the next section, however, bureaucratic outsourcing involves its own serious drawbacks. Because outsourcing buffers agencies from horizontal accountability institutions, the outcomes for bureaucratic capacity and good governance depend on the broader political context. Even when driven by public-spirited officials, bureaucratic outsourcing may limit state capacity in the long run, even if it maximizes effectiveness in the short run.

To make this argument, I focus on evidence from two widely documented pockets of effectiveness in Brazil that are otherwise quite different: the Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer program and the AIDS program (Flynn Reference Flynn2015; Galvão Reference Galvão2000; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2009; Nunn Reference Nunn2009; Parker Reference Parker2003; Rich Reference Rich2019; World Bank 2004b). Bolsa Família was created in 2003 under a left-wing government during a period of economic prosperity. In contrast, the AIDS program was constructed in 1994 and expanded under a centrist government during a period of economic crisis. Yet Bolsa Família and the AIDS program similarly developed high-functioning agencies to run them, characterized by committed and capable bureaucrats. Moreover, both bureaucracies were built during the era of heightened accountability beginning in the 1990s. We would expect Brazil’s new accountability mechanisms to have caused strong bureaucratic capacity within these new national social programs. Contra this expectation, I use qualitative methods to show that these programs developed bureaucratic capacity despite accountability mechanisms.

This argument contributes to a growing body of literature on nonstate provision of social welfare. Previous research has focused on the consequences of outsourcing public services to nonstate organizations for government accountability to citizens and for citizen–state relations more broadly (Brass Reference Brass2016; Cammett and Maclean Reference Cammett and Maclean2014; Nelson-Nuñez Reference Nelson-Nuñez2019; Post, Bronsoler, and Salman Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017). Others have focused on how outsourcing affects—and is affected by—the abilities of politicians to claim political credit for public services (Boulding and Gibson Reference Boulding and Gibson2008; Bueno Reference Bueno2018). In contrast, this article sheds new light on the motivations that drive policymakers to outsource social programs, and on the consequences of outsourcing for building state capacity.

The next section elaborates the argument in the context of the extant literatures on bureaucratic capacity and accountability. I then explain the logic of case selection and make the methodological case for a qualitative approach to analyzing public sector reform. Subsequent sections use original evidence from Brazil to probe my argument. Drawing on 41 interviews conducted across six months of fieldwork, I first reveal the unintended consequences of accountability reforms in Brazil: red tape that threatened to strangle fledgling social sector programs. I then conduct a plausibility probe of my argument about bureaucratic outsourcing using the cases of Bolsa Família and the AIDS program. Next, I provide evidence to show these two programs represent a broader national pattern. In the penultimate section, I address the vulnerabilities of this alternative approach to bureaucratic development. I conclude with a broader discussion that sets the agenda for a new approach to studying public sector reform.

Bureaucratic Capacity and Accountability

Weak bureaucratic capacity is a primary factor in explaining why so many countries fail to promote development. What, then, constitutes a capable bureaucracy? Although definitions vary (Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017, 3–7), many political scientists draw on Weber (Reference Weber1968) to focus on two organizational features that characterize high-quality agencies (Berwick and Fotini Reference Berwick and Fontini2018; Evans and Rausch Reference Evans and Rausch1999; Geddes Reference Geddes1990a; Rothstein and Teorell Reference Rothstein, Teorell, Holmberg and Rothstein2012). First, they employ capable and committed bureaucrats. Second, they can control their budgets, without interference by politicians. Bureaucracies across the developing world are seen as lacking these attributes and therefore unable to promote development and social welfare programs (Evans and Rausch Reference Evans and Rausch1999). Although bureaucratic capacity does not necessarily result in successful programs, successful programs require capable bureaucracies that can get things done.

In the Global South, the challenge of building bureaucratic capacity is often analyzed through the lens of corruption (Ang Reference Ang2017; McDonnell Reference McDonnell2020, 1–4). Scholars and development practitioners commonly assume states are populated by self-interested politicians and civil servants, who will siphon money from the state if free from oversight. In this view, rampant corruption is a primary reason that developing-world bureaucracies are incapable of performing core functions.

With corruption seen as a driver of weak bureaucratic capacity, good-governance reformers have focused on initiatives to promote horizontal accountability: building state institutions that hold other public agencies and branches of government accountable for obeying laws (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1999; Schedler, Diamond, and Plattner Reference Schedler1999). New procurement regulations and civil service exam requirements control how bureaucrats spend money and whom they can hire. Auditing agencies have acquired new powers to monitor the activities of bureaucrats (Casas-Zamora and Carter Reference Casas-Zamora and Carter2017). Accountability initiatives such as these, focused on limiting opportunities for corruption, have received almost universal praise from international development organizations (Transparency International 2012).

Yet, despite the global spread of accountability institutions, bureaucratic capacity in the developing world remains strikingly uneven, even within countries (Bersch Reference Bersch2019; Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Reference Bersch, Praça and Taylor2017b; Dargent, Feldmann, and Luna Reference Dargent, Feldmann and Luna2017; Lopez and Praça Reference Lopez, Praça, Pires, Lotta and de Oliveira2018; Niedzwiecki Reference Niedzwiecki2018; Soifer Reference Soifer2008; Souza Reference Souza2017; Touchton, Sugiyama, and Wampler Reference Touchton, Sugiyama and Wampler2017). Although quantitative measures of bureaucratic capacity are often positively correlated with quantitative measures of accountability, studies also reveal large numbers of exceptions and unexplained cases (Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Reference Bersch, Praça, Taylor, Centeno, Yashar and Mistree2017a; Ferrali and Kim Reference Ferrali and Kim2020).

In light of such limited results, some analysts of good governance have turned away from accountability frameworks that emphasize fighting corruption (e.g., Fox Reference Fox2022; Bertelli et al. Reference Bertelli, Hassan, Honig, Rogger and Williams2020; Johnston Reference Johnston2005; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015). These authors focus on other drivers of “high-quality” bureaucracies, such as the alignment of interests between bureaucrats and the public (Tendler Reference Tendler2007), recruitment practices that favor dedicated, hard-working individuals (McDonnell Reference McDonnell2020, 26–520), or broader structural shifts toward deepening democracy (Johnston and Fritzen Reference Johnston and Fritzen2021). Others argue that Weberian bureaucracies may not even be universally desirable—that alternative types of bureaucracies, such as those that collect their own revenues, may be more suitable for developing countries (Ang Reference Ang2017). Until now, however, few studies have examined the mechanisms through which accountability initiatives targeted at fighting corruption affect bureaucratic capacity (Bertelli et al. Reference Bertelli, Hassan, Honig, Rogger and Williams2020; Meier et al. Reference Meier2019; Polga-Hecimovich and Trelles Reference Polga-Hecimovich and Trelles2016).

This article joins a nascent body of scholarship calling attention to potential drawbacks of anticorruption initiatives for building high-quality bureaucracies (e.g., Biradavolu et al. Reference Biradavolu, Blankenship, George and Dhungana2015; Wang Reference Wang2022). As Toral (Reference Toral2019) shows, anticorruption initiatives can motivate outgoing mayors to dismiss experienced bureaucrats as a way of avoiding potential prosecution by cleaning the accounts, leading to temporary reductions in bureaucratic performance. Others have shown that procurement audits on public auctions, designed to prevent corruption in government spending, can decrease transparency by incentivizing bureaucrats to avoid public auctions altogether (Gerardino, Litschig, and Pomeranz Reference Gerardino2017). Together, these studies break from our common understanding of anticorruption initiatives as wielding either a net positive or a net neutral effect by highlighting contexts in which they can hinder the development of capable bureaucracies.

Compliance Burden as a Barrier to Building Bureaucratic Capacity

Drawing on “red tape” literature in the field of public administration, this article highlights a new mechanism through which anticorruption initiatives can limit bureaucratic capacity: compliance burden. In public administration scholarship, compliance burden refers to the total resources an agency expends in complying with a rule (Bozeman and Feeney Reference Bozeman and Feeney2011, 38). Whereas scholarship on developing countries tends to focus on the challenge of corruption as limiting bureaucratic capacity, public administration scholarship—still largely based in the Global North—tends to view compliance burden as the main challenge.

Yet, in practice, the challenges of corruption and compliance burden are linked. Anticorruption initiatives keep bureaucrats in check by forcing them to comply with an abundance of accountability rules. But bureaucrats who adhere to these rules must pay heavy compliance costs. Public-spirited bureaucrats thus confront a trade-off between adhering to accountability rules and maximizing their agency’s bureaucratic capacity.

Civil service exam requirements illustrate the trade-off between combatting corruption and building bureaucratic capacity. These rules, designed to crack down on corruption and clientelism in hiring within bureaucracies, demand that all would-be civil servants take rigorous exams. Exams are typically graded blindly, and hiring is determined narrowly based on exam scores. Measures such as these are almost universally praised (Transparency International 2012). Overlooked by most, however, is that these exams impose heavy burdens, both on would-be bureaucrats and on the agency directors in charge of hiring. For would-be bureaucrats, taking these exams requires months of study and, often, expensive test-preparation courses. Policy experts, especially those who already hold prestigious jobs, have little incentive to invest the time and money required to pass a public entrance exam. Even if they chose to submit to a civil service exam, experts in a highly specialized field may not achieve the highest score on an exam that tests for broad knowledge across subject areas. Civil service exam requirements can thus limit the ability of agency directors to hire the most capable and committed bureaucrats by preventing them from selectively recruiting policy experts.

Procurement regulations, intended to crack down on corruption in government spending, similarly impose compliance costs. Procurement regulations require bureaucrats to do things such as open public bids for purchases of equipment or services. Public bids force bureaucrats to assemble complex paperwork, wait for months while companies prepare their bids, and spend further time reviewing bids and justifying their selections. Bureaucrats’ budgets may even expire while they are waiting for approval to make purchases. Procurement regulations can thus impede bureaucrats from spending their budgets—another core organizational feature of bureaucratic capacity.

Whereas existing red tape literature focuses on the negative effects of compliance burden for government bureaucracies in the Global North, these costs may be particularly acute for bureaucracies that promote social inclusion in developing countries—especially new ones, as capacity is built over time. Anticorruption initiatives took effect across the developing world in the 1990s and early 2000s, during the very period that witnessed an unprecedented extension of government programs to serve the poor and otherwise marginalized. To build and institutionalize these programs, agency directors needed to hire entire teams of experts and to establish the infrastructure for implementing those programs—tasks that are commonly impeded by accountability rules. New social programs created after the turn toward anticorruption initiatives are therefore likely to suffer from compliance burden.

At the same time, public sector officials face limited options for escaping such compliance costs. In most cases, lobbying politicians to reform the rules governing bureaucracy is not a viable option. Successful efforts at public sector reform require the support of broad societal coalitions, which are hard to cultivate (Doner and Schneider Reference Doner and Schneider2017; Holland and Schneider Reference Holland and Schneider2017). In a context of empowered accountability institutions, public officials are also disincentivized from simply ignoring the rules; those who ignore them risk punishment ranging from fines to jailtime.

Outsourcing Bureaucracy to Evade Accountability

Yet, underacknowledged by public-administration scholarship, the directors of bureaucratic agencies have pursued a range of legal loopholes to avoid the compliance costs of anticorruption rules. For example, they have cooperated with semiautonomous agencies that are staffed by civil servants but have their own revenues and assets—allowing them to avoid government procurement rules. Similarly, agency directors have sought permission for “emergency” procedures that allow them to subvert procurement rules on a case-by-case basis—for example, to speed the process of purchasing urgent medical supplies. Agency directors have also used their arsenal of political appointments to recruit technocratic policy experts into their agencies—thus avoiding civil service exam requirements. Finally, agency directors have engaged in bureaucratic outsourcing—outsourcing entire government agencies to nonstate organizations, which can in some cases allow them to skirt anticorruption measures altogether. This article focuses on bureaucratic outsourcing as a legal-loophole strategy that is particularly effective for capacity building by virtue of its ability to buffer agencies from a wide range of accountability rules as well as from government enforcement agencies.

Bureaucratic outsourcing was made available as a strategy by the ascendancy of the “new public management” approach to governance—an approach intended to make government more “businesslike” by increasing efficiency and competition. This approach gained traction in the Global North in the 1980s in response to prior anticorruption measures instituted in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries that were intended to legitimize bureaucracies through accountability rules. In practice, these rules had opened bureaucracies to new lines of critique, “bemoan[ing] the overabundance of procedure as the enemy of efficient and rational government” (Rocco Reference Rocco2013, 767). Adherents of the new public management approach, driven by a concern with compliance burden, thus began to advise governments across the world to outsource local service delivery to private entities in order to increase efficiency and improve performance. Soon after, political leaders adopted the tenets of new public management theory to promote other goals as well. Accordingly, OECD countries outsourced local provision of public services to nonstate actors as a strategy for shrinking welfare states and reducing government expenditures on social services. Developing countries outsourced local service provision to nonstate actors in order to expand services into areas beyond the state’s reach (Brass Reference Brass2016; Cammett and Maclean Reference Cammett and Maclean2014; Nelson-Nuñez Reference Nelson-Nuñez2019; Post, Bronsoler, and Salman Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017).

In this article, I show that the trend toward “new public management” motivated policy makers to outsource not just the local agencies that implement policy but also the core national bureaucracies that establish and regulate policy. Directors of national agencies, leveraging the broader trend, outsourced administrative operations for their own national bureaucracies to nonstate actors as a strategy for avoiding anticorruption regulations. By disaggregating the work of government bureaucracies into discrete “projects” and subcontracting nonstate organizations to administer those projects, agency directors could escape government regulations on hiring and procurement, following instead the rules of their subcontractors. Although the legal constraints that govern outsourcing vary across countries, nonstate organizations typically operate under fewer regulations than government agencies do. Many democratic governments allow nonstate organizations to follow at least some of their own rules and procedures when taking over public-administration duties—even when they conflict with government rules. Moreover, the rules governing subcontracting are often vague; they depend on the phrasing of specific signed agreements, making them easily subject to manipulation. The directors of national government agencies across the world have thus used outsourcing as an institutional bypass strategy (Prado and Trebilcock Reference Prado and Trebilcock2018) to escape government accountability rules and regulations.

Although the practice of bureaucratic outsourcing to avoid accountability has not yet been rigorously analyzed, anecdotal evidence suggests it is a widespread phenomenon. Across the Middle East, agencies such as the World Bank finance and staff “parallel bureaucracies” that “bypass recipient institutions, and, in some instances, recipient political authorities” in administering public policies (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman2013, 335). Across Latin America, United Nations agencies administer “technical cooperation projects” as a vehicle for selectively recruiting policy experts into government agencies through consultant contracts—experts who play central roles in designing and regulating new public policies (Zuvanic and Iacoviello Reference Zuvanic and Iacoviello2010, 32). Even in Washington, DC, for-profit corporations known as “belt-way bandits” administer much of the work of government agencies.

At the same time, we should expect the implications of this practice for bureaucratic capacity to vary depending on the surrounding political environment. When policy makers outsource bureaucracies, they buffer government agencies from other arms of the state that would otherwise serve as a check on their power. Whether bureaucratic outsourcing strengthens or hinders bureaucratic capacity thus depends on political context. In a context of broad political will to improve government policy, we should expect bureaucratic outsourcing to produce capable government bureaucracies. In other cases, however, public officials could outsource bureaucracies to pursue partisan or personal goals that lead to negative outcomes. Similarly, the outcomes of bureaucratic outsourcing depend on the characteristics of the nonstate organizations that serve as venues. Because outsourced agencies are buffered from governmental accountability, we should expect bureaucracies that are outsourced to private corporations (driven by profit motives and accountable to individual shareholders) to be affected differently than are bureaucracies outsourced to United Nations agencies (driven by developmental goals and accountable to multiple governments) or to nongovernmental organizations hired through loans supported by United Nations agencies.

Even when public sector officials use nonstate organizations to build more capable bureaucracies, there may be trade-offs between building shadow state capacity in the short run and strengthening state capacity in the long run. Whereas outsourced bureaucracies may be highly capable, they are uninstitutionalized and therefore vulnerable to changes in the political environment. When a new president comes to power, they can reduce, weaken, or even dismantle outsourced bureaucracies simply by refusing to renew their contracts. Just as with the costs of “red tape,” the political vulnerabilities that go along with bureaucratic outsourcing may be especially relevant to newly constructed social, environmental, and human rights programs in developing countries now that presidents who are intent on rolling back policies for marginalized groups have gained power in many countries.

This theoretical framework sets an agenda for public administration scholarship to examine regional patterns in bureaucratic outsourcing, and patterns in public sector outcomes across different types of organizations that serve as venues. In the following section, I use the case of Brazil to illustrate the practice of outsourcing bureaucracy to evade accountability and to spark diverse questions for future studies to explore.

Case Selection and Methods

Brazil is an extreme case of government investment in anticorruption initiatives and thus offers a useful lens for new theorizing. Following the completion of democratic transition in 1989, Brazil instituted new accountability rules and endowed multiple institutions with broad powers to pursue, expose, and sanction corrupt activities (Power and Taylor Reference Power and Taylor2011; Taylor and Buranello Reference Taylor and Buranello2007). These accountability institutions have received high praise for their autonomy and enforcement power (Avis, Ferraz, and Finan Reference Avis, Ferraz and Finan2018; Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Reference Bersch, Praça, Taylor, Centeno, Yashar and Mistree2017a; Speck Reference Speck, Power and Taylor2011; Taylor and Buranello Reference Taylor and Buranello2007).

Within this context of heightened accountability, Brazil constructed many new national programs to promote social inclusion in the 1990s and early 2000s. These agencies, created after Brazil’s anticorruption rules and enforcement mechanisms had already been implemented, were therefore especially sensitive to their effects. We might thus consider Brazil’s new social programs, collectively, to be a most-likely case for observing the supposed positive effects of anticorruption initiatives on bureaucratic capacity.

In practice, however, these new accountability initiatives had no clearly discernible effect. Into the 2000s, bureaucratic capacity varied widely across government ministries and agencies (Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Reference Bersch, Praça, Taylor, Centeno, Yashar and Mistree2017a; Reference Bersch, Praça and Taylor2017b; ENAP 2018; Pires, Lotta, and Oliveira Reference Pires2018). Moreover, Brazil’s new social sector ministries ranked weaker than average on quantitative measures of state capacity (Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Reference Bersch, Praça and Taylor2017b, 117). According to the dominant thinking, this overarching failure to strengthen bureaucratic capacity might suggest that Brazil’s accountability initiatives were not adequately implemented.

Yet a handful of new national social programs stood out as pockets of effectiveness—programs that employed capable and committed policy experts and executed their budgets without political interference—inside otherwise dysfunctional government ministries. Moreover, some of these experts were activists who had already been pushing for policy reform prior to taking jobs in government (Abers Reference Abers2019; Abers and Tatagiba Reference Abers, Tatagiba, Rossi and von Bülow2015; Hochstetler and Keck Reference Hochstetler and Keck2007). These bureaucrats had reputations for creativity and innovation in confronting the myriad challenges to policy implementation in Brazil (Abers and Keck Reference Abers and Keck2013; Rich Reference Rich2019). Unexplained by existing scholarship is how these new government programs developed such capable national bureaucracies.

Drawing on 41 semistructured interviews, I use qualitative methods to generate new hypotheses about the relationship between accountability initiatives and bureaucratic capacity. Interviewees were divided into four categories, with particular attention to divergence in their incentives vis-à-vis bureaucratic outsourcing. I interviewed 17 mid-level bureaucrats across five ministries as well as 15 top officials in the UN agencies that administered most outsourced bureaucracies. Both groups had incentives to promote outsourcing. But I also interviewed the entire team of auditors in charge of enforcing accountability rules and the entire team of officials who controlled Brazil’s international cooperation agreements. These groups sought to eliminate outsourcing. Interviewees across all categories reported the same causes and consequences of bureaucratic outsourcing, even if they disagreed about whether the practice should continue. (See Interview Methods Appendices A and B.)

I use my interviews first to trace the broad effects of national accountability initiatives introduced in the 1980s and 1990s across an array of social sector programs. Contrary to scholarly expectations that accountability initiatives should strengthen capacity, I show how they instead produced red tape that threatened to strangle fledgling social sector programs.

I then conduct a plausibility probe of my argument about how some programs escaped the negative effects of accountability rules by zooming in on two pockets of effectiveness that are otherwise quite different (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005, 75; González Ocantos Reference González Ocantos, Curini and Franzese2020): the Bolsa Família cash transfer program and the AIDS program. Both the Bolsa Família cash transfer program (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2014; Soares, Ribas, and Osório Reference Soares2010; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2013) and the AIDS program (Flynn Reference Flynn2015; Galvão Reference Galvão2000; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2009; Nunn Reference Nunn2009; Parker Reference Parker2003; Rich Reference Rich2019; World Bank 2004b) have been praised internationally for their capable and committed bureaucrats and for the effective use of their budgets. Yet Bolsa Família and the AIDS program score differently on variables commonly thought to produce capable social welfare programs. Whereas Bolsa Família was created under left-wing party rule, the AIDS program was built under centrist party rule. Moreover, Bolsa Família was built during a time of economic prosperity in the early 2000s, whereas the AIDS program was built an economic crisis in the mid-1990s. Conventional wisdom suggests that Bolsa Família, created under left-wing rule during a time of economic prosperity, should have developed more bureaucratic capacity than did the AIDS program. By carefully tracing the process through which both of these otherwise dissimilar programs successfully built institutional capacity, I am thus able to demonstrate that my argument about bureaucratic outsourcing is plausible in different contexts where the same outcome is observed. I complement my case comparison with additional data to suggest these two programs represent a broad pattern among social inclusion programs of the same period.

Background: Brazil’s Accountability Institutions

Throughout the twentieth century, clientelism and corruption posed significant barriers to strengthening bureaucratic capacity in Brazil. Brazilian politicians famously doled out vast numbers of bureaucratic jobs and contracts to political supporters—overlooking the most qualified personnel and the most competitive suppliers. Moreover, legislators often diverted agency budgets toward their own pet projects. The combined effect of such practices was poorly funded bureaucracies run by poorly trained bureaucrats and—as a consequence—egregious displays of bureaucratic incompetence (Geddes Reference Geddes1990).

In the 1980s, however, democratization provided modernizing elites an opportunity to build new accountability mechanisms into bureaucracy. During the country’s constitutional convention, two policy communities with different motivations led this effort (Praça and Taylor Reference Praça and Taylor2014, 5). The economic policy community sought to strengthen state capacity for promoting economic development and solving the country’s hyperinflation crisis. Meanwhile, the legal rights community sought to strengthen state capacity for promoting social policy development and human rights protections. Both goals required capable national bureaucracies. Thus, both communities pushed to strengthen government accountability mechanisms as a strategy for limiting the corruption that had traditionally drained bureaucratic capacity.

These efforts led Brazil to develop a rigid set of accountability rules and a powerful set of auditing institutions to enforce them (Mainwaring and Welna Reference Mainwaring and Welna2003, 20; Power and Taylor Reference Power and Taylor2011, 9; Praça and Taylor Reference Praça and Taylor2014). Detailed accountability rules closed the loopholes that allowed corrupt practices to flourish within government. Auditing institutions—along with the federal police, the public prosecutor’s office, and the courts—enforced Brazil’s new accountability rules. A fundamental goal of these initiatives was to strengthen bureaucratic capacity—a necessary precondition for improving bureaucratic performance—by reducing corruption (Speck Reference Speck, Power and Taylor2011, 139).

Two of the main accountability rules created during this period were civil service exam requirements and procurement regulations. Civil service exams, while not new, gained de facto power through Article 37 of Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, which mandated public entry exams for hiring most civil servants. The reform combatted clientelism by banning the recruitment of government employees through private contracts. Analysts almost universally praised this measure, interpreting the spread of formal entrance exams as evidence that Brazil was developing a Weberian bureaucracy through promoting accountability (Nunberg and Pacheco Reference Nunberg, Pacheco and Schneider2016; Pereira Reference Pereira2016).

Procurement rules—regulations on government purchases—were also given the force of constitutional decree. As with civil service reform, Brazil’s new procurement regulations were designed to root out corruption by means of detailed rules. Rigid public bidding requirements, for all purchases from large construction contracts to basic office supplies, were established as a means of reducing the discretion of contracting officials and thus eliminating opportunities for corruption (Bersch Reference Bersch2019, Chapter 5).

At the same time, national auditing institutions were either created from scratch or imbued with new enforcement powers. Brazil’s main auditing agency, the TCU (Federal Accounting Tribunal), was transformed into a powerful oversight agency. A separate auditing agency for the executive branch was also created, called the CGU (Federal Comptroller’s Office) (Abrucio, Loureiro, and Pacheco Reference Abrucio2010; Loureiro et al. Reference Loureiro2012, 56–7; Praça and Taylor Reference Praça and Taylor2014, 18). Both auditing institutions were imbued with powerful legal weapons to identify government misconduct, pursue investigations, and recommend punishment for misbehavior (Speck Reference Speck, Power and Taylor2011, 135–49).

Although political corruption remained a major challenge, bureaucratic corruption diminished significantly after the 1980s (Pires, Lotta, and Oliveira Reference Pires2018). Yet Brazil’s accountability institutions failed to improve bureaucratic capacity. As recent audit reports show, bureaucracies continued failing to properly spend their budgets in the 2010s—negatively affecting the performance of public programs. This time, however, the principle cause was no longer corruption but, rather, bad management (Loureiro et al. Reference Loureiro2012, 60). The following section contributes to explaining why anticorruption initiatives failed to improve bureaucratic capacity, by revealing the hidden costs of compliance.

Accountability Rules and Red Tape

Contrary to the dominant wisdom that accountability and state capacity go hand in hand, interviews with public sector officials suggest that the very mechanisms designed to promote accountability in fact limited opportunities for building capable government bureaucracies. Civil service regulations, while reducing opportunities for patronage, limited opportunities for hiring policy experts into government. Procurement regulations, designed to prevent collusion in government contracting, prevented bureaucracies from making essential purchases. Together, these accountability rules threatened to strangle new bureaucracies with red tape. Such administrative hurdles posed a threat to program builders across a wide variety of agencies created to promote social and human rights during the 1990s and early 2000s.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, hiring policy experts into government became a broad priority when social movements drove a new period of policy development in Brazil. Two successive presidents, from different parties, transformed policy promises for marginalized groups into concrete benefits and protections by creating new government agencies. Both presidents, committed to making government policy more inclusive, used political appointments to hire renowned policy experts as directors of these agencies.

In turn, agency directors needed policy experts to design and build their programs. For example, Bolsa Família—Brazil’s flagship antipoverty program—was created in 2003 and housed in the new Ministry for Social Development. According to one of the bureaucrats who built the program,

Bolsa Família was very small, and the program needed a different profile of person than what they currently had in their tiny team. They needed technical capacity to build the system. The budget for Bolsa Família had increased a lot with this new Ministry, but without a big team to administer it.Footnote 3

In other words, the main challenge to building Bolsa Família at the outset was not attracting financial resources but, rather, human resources.

Recruiting outside policy experts to join these agencies was important during this early phase. Because Brazil’s new federal programs covered issues that had previously been neglected by government, experts on these policies worked outside the state. Brazil’s civil service exam requirements, designed to prevent corruption in hiring, posed three challenges to recruiting outside experts.

First, no specialized entrance exams existed to channel expertise in social, environmental, or human rights policies. Whereas Brazil’s economic ministries had developed specialized entrance exams during the Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) period of the twentieth century, social policy ministries had remained bastions of clientelism. In the late 1990s, not even the oldest social policy ministries, such as the ministries of health and education, had developed their own entrance exams (Souza Reference Souza2017, 11–2). New entrance exams would thus have to be designed to recruit policy experts into Brazil’s new government programs—a process that was both expensive and slow. In other words, entrance exam requirements made it impossible to quickly staff new agencies with policy experts through standard channels.

Second, entrance exam requirements made it less appealing for outside experts to apply for government jobs. Nearly all exams consisted of multiple-choice tests that covered a wide array of topics, including general subjects such as math and literature. Moreover, civil service regulations mandated that hiring decisions be exclusively based on who achieved the highest score. These exams were also highly competitive—sometimes attracting thousands of candidates. An entire for-profit industry offered months-long exam-preparation courses. Highly specialized experts who were already employed—such as doctors, lawyers, or scientists—had little incentive to study for an exam that tested for broad knowledge beyond their expertise. In the words of a former bureaucrat in the Ministry for Human Rights, “there’s no guarantee that someone with an advanced degree, who has already spent ten, twenty years of their life studying their specific subject area, is going to study to take an exam to do public policy.”Footnote 4

Third, many of Brazil’s entrance exams were paradoxically biased against the best qualified experts who took them. This hurdle to recruiting experts was especially problematic for social programs that had been created because of social-movement pressure. In these cases, activists were often the only people with any policy experience. As the same informant explained,

sometimes an activist is a major national leader, but he doesn’t have the [academic background to pass] a civil service exam. […] The civil service exam is a joke, because you end up hiring the guy who spent five years of his life studying specifically to pass the exam, nothing else.Footnote 5

Although activists were sometimes the best qualified experts to design government programs, they were unlikely to be recruited through a standardized hiring procedure based strictly on exam scores.

Procurement rules posed similar problems. Although procurement regulations were designed to prevent corruption in government spending, interviews revealed that, in practice, they prevented bureaucracies from acquiring essential supplies. The main challenge was that procurement regulations introduced long delays between when a spending decision was made and when that money could actually be used. Even in the most efficient processes, it took bureaucrats months to comply with all the legal requirements to make a purchase. For example, rather than choosing their own supplier, bureaucrats were forced to allow companies to bid on contracts. This bidding process—only one of many phases in the procurement process—was slow. To give companies enough time to participate in the bid, bureaucrats were obligated to allow 30 to 45 days for small-scale purchases, 60 to 90 days for medium-sized purchases, and 90 to 150 days for large-scale purchases (Motta Reference Motta2010). In a best-case scenario, it would take a bureaucrat who played by the rules a minimum of two months to make even a basic purchase such as a computer.

In practice, the businesses competing for contracts often introduced additional delays by lodging complaints that bureaucrats were then forced to review. For example, all participants in a bid were allowed to review the documents submitted by other participants—a rule designed to ensure transparency and accountability. According to one analysis, however, “this stage is considered one of the most complex and lengthy process of bidding, as the smallest error, mistake or omission will be used by bidders in an attempt to disqualify the others, action which can trigger a series of complaints, substantially delaying the process” (Motta Reference Motta2010, 8). According to an account from the Ministry of Health, “purchasing basic pharmaceutical products often took well over six months and could stretch on for years if the process ended up in court” (Bersch Reference Bersch2019). As a World Bank procurement assessment for Brazil describes,

the constant stream of procurement disputes results in delayed contracting and purchasing. The numerous administrative complaints (recursos) and injunctions issued by courts of law (medida liminar or antecipação de tutela) may hold up the bidding by many months if not years (2004a, 2).

In interviews, bureaucrats across five ministries corroborated this account.

Brazil’s slow procurement process was especially problematic for bureaucracies requiring urgent supplies—such as medicines and hospital equipment for programs in the Ministry of Health. In these cases, bureaucrats resorted to “emergency” procedures that allowed them to subvert standard procedures and instead chose their suppliers without price justifications. Given the predictability of long delays, the use of such “emergency procedures” quickly became the norm. According to one 1997 estimate, emergency procedures were used for over 70% of contracts—which, in turn, opened new opportunities for corruption (Bersch Reference Bersch2019, 220).

Brazil’s procurement rules were so time and labor intensive that they often rendered fledgling government bureaucracies incapable of using their budgets at all. In Brazil, state agencies had only 12 months to spend their annual budgets before losing their funds, in contrast to the more flexible multiyear spending cycle for most OECD countries (Blöndal, Goretti, and Kristensen Reference Blöndal, Goretti and Kristensen2003). Moreover, Brazil was one of the few OECD countries that did not allow government organization managers to keep any savings from efficiency gains to be used on other projects. In the words of a former bureaucrat in the Ministry of Social Development,

when you manage a government program, you have one year to spend your budget. If you don’t spend it all within that year, your money gets sent back to the national treasury. For example, if I’m in charge of a program to build cisterns and I had planned to build 100,000 but I only managed to build 50,000 within a year, when December comes I’m going to [have to] give away everything that’s left in my budget.Footnote 6

As multiple bureaucrats explained to me, agency directors often received approval to make purchases only after their spending cycle had ended—in other words, only after the money they set aside for a purchase had already disappeared from their accounts.

These qualitative findings are further highlighted in a recent survey of Brazil’s civil service, which captures bureaucrats’ perceptions of challenges they faced in promoting public policy (ENAP 2018). Thirty-five percent of the 2,000 civil servants who responded to the survey reported that they either “frequently” or “always” spent their time responding to demands by Brazil’s auditing agencies (25). The survey’s own authors concluded that this statistic “suggest[s] a dysfunctionality in the public policy process, given that the analytic capacity [of the Brazilian civil service] is not being used directly to produce goods for the betterment of the population but, rather, to attend to the demands of accountability agencies”Footnote 7 (ENAP 2018, 26).

In summary, the immediate challenge to building capable bureaucracies during the 1990s and early 2000s was not corruption but regulatory sclerosis. New accountability rules, while cracking down on corruption, also weighed fledgling bureaucracies down with red tape. Paradoxically, the program directors who complied with all of Brazil’s accountability rules were prevented from performing core duties. Public officials were thus faced with a trade-off: follow government rules versus build capable programs.

An Alternative Approach to Building State Capacity: Outsourcing Bureaucracy

In the following two sections, I offer evidence to suggest the public officials who succeeded in building Brazil’s more capable bureaucracies were those who found ways around accountability rules. I begin by conducting a plausibility probe of my argument by tracing the development of two widely documented pockets of effectiveness that are otherwise quite different, the bureaucracy than runs the Bolsa Família cash transfer program and the AIDS program—programs housed in different ministries, created under different partisan administrations, and built under different economic contexts.

Finding ways to buffer bureaucracies from interference by other parts of government is a time-honored tradition in Brazil, known as “parallel administration” (Geddes Reference Geddes1990; Graham Reference Graham1968; Nunes Reference Nunes1997). However, in a context of empowered accountability institutions policy makers could not copy earlier forms of parallel administration, which had involved authoritarian means—creating special protections for priority policy sectors by fiat. Instead, twenty-first-century modernizers were forced to seek legally sanctioned strategies for parallel administration. Outsourcing bureaucracies to nonstate organizations was one such strategy.

National program directors in Brazil outsourced their bureaucracies to a wide variety of organizations, including private foundations, national universities, and think tanks. Yet United Nations agencies emerged as especially convenient venues for bureaucratic outsourcing for at least three reasons. First, UN agencies enjoyed semisovereign authority within Brazil—exempted from following certain domestic rules and regulations—through international cooperation agreements signed in prior decades (Stern and Defourny Reference Stern and Defourny2001, 19; UNDP 2011, 25). Second, their administrative structure mirrored that of government bureaucracies. And third, UN agencies were already administering Brazil’s loan money—conditions of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, who lacked trust in Brazil’s bureaucracy. By the late 1990s, 22 United Nations agencies, programs, and committees had already established field offices in Brazil (UNDP 2011, 26).

Under the guise of technical cooperation agreements, reform-oriented program directors thus began in the late 1990s to outsource growing numbers of agency operations to UN organizations. Basic budgetary items were incorporated into technical cooperation projects and then transferred from the purview of government to the purview of their UN partner. Accordingly, the UN partner agency would administer all activities within project budgets according to their own internal rules. By entering into technical cooperation agreements with international organizations, program directors could bypass the national rules that limited their ability to build capacity, channeling instead nonstate organizational capabilities.

Informants from both Bolsa Familia and the AIDS program described this strategic use of international organizations in strikingly similar terms. As an informant who had worked with Bolsa Família described, echoing comments by AIDS program informants,

[money for technical cooperation] would be deposited into UNDP, FAO, or UNESCO [bank accounts]. […] You would put the money there, and then you would be able to administer that money with different rules than you would need to use if it were “direct administration” as we say. […] When we put money into the UNDP, FAO, and UNESCO, we escaped [the rules for hiring and procurement].Footnote 8

Bureaucrats in these programs cooperated with international organizations as a tool to circumvent existing government rules.

Agency directors used such “technical cooperation” to subvert both civil service regulations and procurement regulations. To subvert Brazil’s civil service regulations, they leveraged UN agencies as vehicles for hiring personnel—contracting employees not as civil servants but as project “consultants.” In practice, these “project consultants” performed the work of traditional bureaucrats: they had the same responsibilities as bureaucrats, the same work hours, and the same desks inside government buildings. However, by categorizing them as project consultants rather than as government employees, agency directors could pay their salaries out of project funding, which was controlled by their international partner organization. In so doing, agency directors could hire their employees based on the flexible rules of nonstate organizations rather than on the rigid rules of the Brazilian government.

For agency directors, the rules of international organizations had several advantages over government rules for hiring. First, it allowed them to recruit candidates based on their qualifications and experience instead of their exam results. This ability to selectively recruit personnel helped program builders hire individuals with specialized expertise who may not have achieved the highest scores on broad-based exams. It also helped them recruit candidates who already held prestigious jobs and would be unlikely to take the exam in the first place. Similarly, it helped them recruit activist leaders into government.

Second, UN rules helped with recruitment by allowing agency directors to offer higher salaries than Brazil’s standardized public sector wages. According to a former director of the AIDS program, UN agencies could make salary offers attractive enough to recruit the best in the field. Without the salary offers made possible by the UN, he claimed, getting so many highly qualified personnel to move from desirable cities such as São Paulo and Rio to the remote, landlocked capital of Brasília would never have happened.Footnote 9 As an informant who had worked with Bolsa Família explained, “cooperation agreements don’t define how much you can pay people, which means you can pay the market rate. You see? There’s no way I could recruit a demographer with the same salary I would pay an administrator or teacher.”Footnote 10

Third, the United Nations hiring process was much faster the government hiring process. As an informant who had worked with both UNDP and UNESCO explained,

United Nations agencies have more flexible rules. For example, let’s say the government needs a hundred specialists [for a six-month project]. The government has no way to hire a hundred specialists […] in a short period of time. So the government can decide to make a partnership with UNESCO and then ask UNESCO to hire these hundred specialists […]. It’s similar—not the same but similar—to outsourcing. It’s outsourcing. I’m giving the example of UNESCO here, but it could be any UN agency.Footnote 11

In contrast to hiring personnel through traditional channels, which often took a year or more, hiring UN consultants involved fewer layers of approval and could be completed in a matter of weeks. Program directors thus leveraged the rules of UN agencies to quickly staff new government bureaucracies with policy experts.

Using the rules of international organizations also helped the program directors of Bolsa Família and the AIDS program hire committed bureaucrats who cared deeply about these policies. In contrast to civil service exams, which attracted individuals interested in working as permanent civil servants, selective recruitment meant that agency directors hired individuals based on their dedication to agency-specific issues. Whereas civil servants advanced their careers by moving across different government agencies, these bureaucrats advanced their careers within their specific policy areas, both inside and outside government. Moreover, none of these bureaucrats were political appointees; therefore, they pursued career advancement by achieving agency goals rather than by demonstrating partisan loyalty. Multiple informants and external evaluations emphasized the capability and work ethic of bureaucrats who were contracted as consultants through UN agencies. According to a World Bank official who had evaluated Brazil’s HIV/AIDS programs, “I was blown out of the water at how good they were.”Footnote 12

Agency directors in the 1990s and early 2000s used this strategy not to hire temporary experts onto their teams but rather to build their core workforce. According to a former bureaucrat in Bolsa Família,

as soon as I arrived [in the Ministry for Social Development], I met with the Secretary of Food Security. And even today I still remember the fact that he gave me, because I was so shocked when I heard it: sixty-seven percent of his workforce, in 2010, was made up of consultants.Footnote 13

Similarly, a former AIDS program director recalled that, during his tenure, all staff members had been hired as UN consultants except for him and his secretary.Footnote 14 According to a 2011 study, 200 out of 219 employees working in the AIDS program were technically UN consultants (Arnquist, Ellner, and Weintraub 2011). According to multiple informants from both Bolsa Família and the AIDS program, the “UN consultants” who worked in these agencies were generally responsible for the most important project design and implementation tasks, which sometimes generated jealousy among career civil servants, who were relegated to more boring administrative jobs.

Although, on paper, these bureaucrats held only temporary contracts to complete short-term projects, in practice agency directors continuously renewed them. According to a 2001 UNESCO evaluation, 57% of the 72 projects in operation in Brazil had already been extended at least once. As one of my interview informants described, “you can find people [in the Health Ministry] who have worked there for years, without being civil servants, hired on a provisional basis through renewed contracts.”Footnote 15 Often, these project consultants generally served much longer terms within a single agency than did traditional civil servants.

Just as with civil service regulations, agency directors used UN organizations to subvert Brazil’s procurement regulations by leveraging them as vehicles for spending their budgets on equipment and supplies. In contrast to government procurement rules, which introduced multiple layers of administrative requirements as a strategy for promoting accountability, the UN procurement process was comparatively simple and efficient (de Morais Reference de Morais2003). For example, UN rules allowed bureaucrats to choose their own supplier and send their purchase requests directly to a team of three procurement specialists. This team collectively decided whether to approve the request, and they would immediately communicate their decision to the bureaucrat requesting approval. Moreover, their decision was binding: companies that were not chosen as suppliers had no right to appeal the procurement team’s decision.

Multiple informants described how they used UN rules to speed up the purchasing process. As a former director of UNESCO’s Brazil office recollected,

one time there was a vaccine supply crisis, and so we had to bring in an enormous quantity of vaccines into Brazil. Using the normal Brazilian government process, it would have taken three more months [to get the vaccines] […]. UNESCO managed to acquire and bring the vaccines [into Brazil] immediately.

This was a dramatic instance of how UNESCO helped Brazil’s AIDS program spend its budget, but it also represented the type of story told to me by many of my informants.

United Nations organizations also helped these bureaucracies preserve their budgets at the end of each fiscal year. Whereas Brazilian rules gave government programs only 12 months to spend their budgets, the UN, like most OECD countries, operates on a multiyear spending cycle (Blöndal, Goretti, and Kristensen Reference Blöndal, Goretti and Kristensen2003). By channeling their budgets into UN organizations, bureaucrats could avoid returning unused funds to the Brazilian treasury. According to another informant who had once worked with Bolsa Família, “one of the main reasons we had for seeking technical cooperation agreements was to not have to return money to the treasury at the end of every year.”Footnote 16

Broader Evidence of Outsourcing Bureaucracy to Evade Accountability

The previous section focused on Bolsa Família and the AIDS program to illustrate how agency directors outsourced their bureaucracies to escape accountability requirements. In my fieldwork, however, I collected similar accounts from agencies across five government ministries. Here I offer evidence to suggest these two programs represent a national trend.

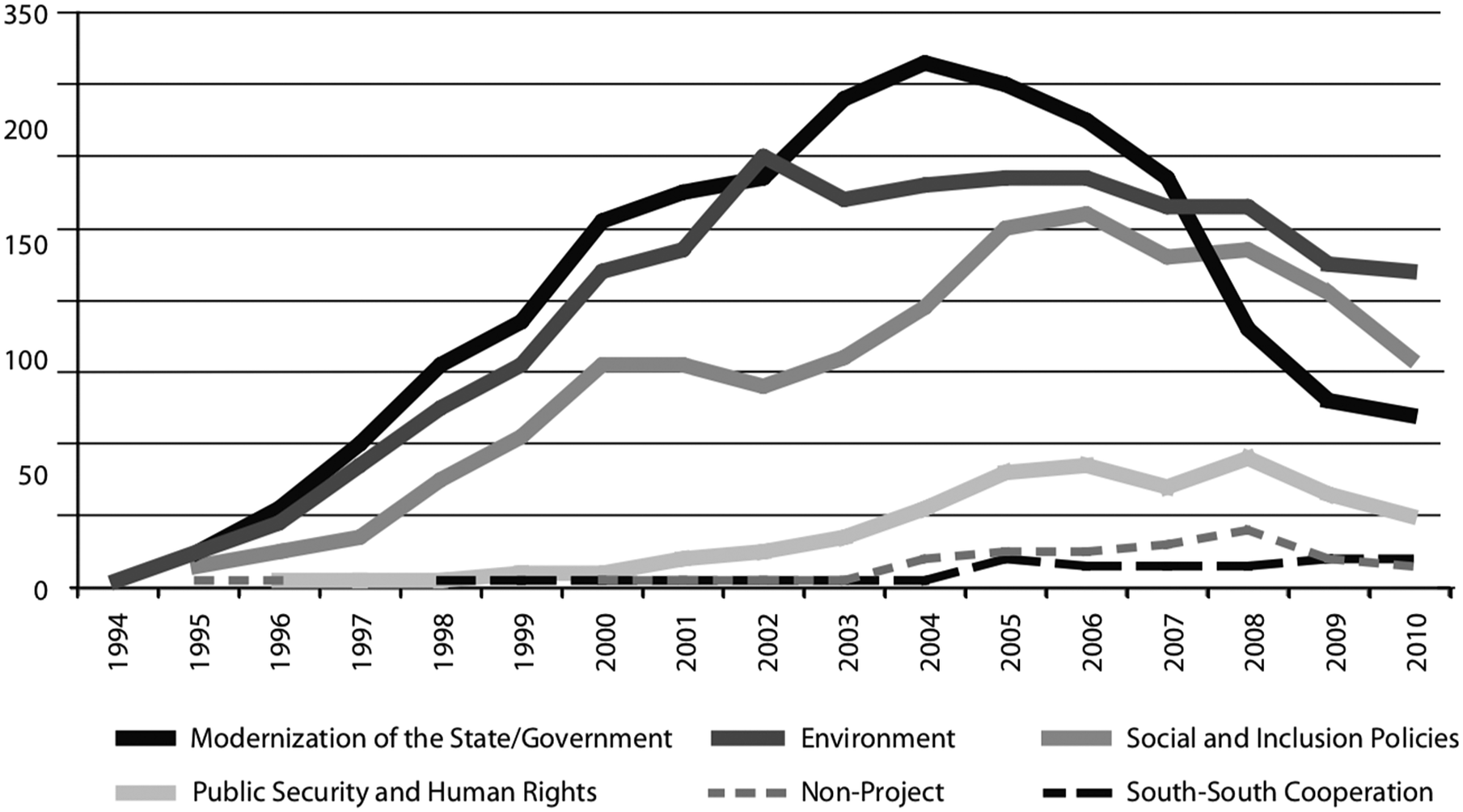

As quantitative indicators show, Brazil sought large numbers of technical cooperation projects from the mid-1990s through the early 2000s, just as new social programs were created. As a 2011 report reveals, the UNDP operated no technical cooperation projects in Brazil before 1996 but jumped to managing over 200 projects per year by 2005 (UNDP 2011, 31; Figure 1). Moreover, these projects were concentrated among social sector programs. The UNDP administered 103 projects to promote “social and inclusion policy” between 1994 and 2010 (UNDP 2011, 32; Figure 2). During 2001 alone, UNESCO administered 72 projects in the areas of health, education, culture, and human development (de Morais Reference de Morais2003, 31). Technical cooperation was such a widespread practice in Brazil from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s that Brazil’s agency for international cooperation even donated government office space for the UNDP to set up a special center for administering technical cooperation projects (UNDP 2011, 39).Footnote 17

Qualitative and quantitative evidence also suggest that agency directors did not use technical cooperation agreements to acquire international expertise but, rather, to leverage international organizations as project administrators. According to an external evaluation of UNDP operations in Brazil,

UNDP was perceived by the project participants interviewed as having contributed little substantive knowledge to the projects […]. This is mostly due to the emphasis placed on the project management component within the organization. (UNDP 2011, xii, 70, author’s italics)

In the words of a government auditor, technical cooperation agreements “had nothing to do with the transfer of expertise.”Footnote 18 Even a high-ranking World Bank official acknowledged, “[they’re] just an administrator, that’s all they do. The money comes to the government and the government asks them to manage the payments to the suppliers. They don’t take a position on anything; they don’t make any decisions.”Footnote 19

Interview evidence further suggests that many agency directors used international organizations for hiring their core bureaucratic workforce. An official from UNDP’s Brazil office described,

UN agencies were used to hire entire project staff teams—not actual consultants, but permanent staff who worked inside government ministries. They were contracted [as consultants] by international organizations, but they were permanent project staff of the ministry.Footnote 20

According to a UNESCO official who conducted an audit of UNESCO’s Brazil operations, “it was an addiction. It was much easier for [agency directors] to contract people through that mechanism than to go through the civil servants function.”Footnote 21 Similarly, a government auditor told me that a wide range of technical cooperation organizations were used “blatantly” as “a mechanism for recruiting bureaucrats.”Footnote 22 Another auditor emphasized, “people contracted as consultants worked alongside civil servants. They had a name badge, email account, a desk … they saw themselves as civil servants, doing routine work for the ministry.”Footnote 23

Descriptive statistics paint a similar picture. In 2001, UNESCO and UNDP had contracted 11,059 Brazilians as experts and consultants.Footnote 24 Similarly, a 2002 estimate states that over 8,000 bureaucrats had been hired through international contracts (Gaetani and Heredia Reference Gaetani and Heredia2002, 30). These numbers are especially revealing considering that only around 8,500 civil servants entered the entire federal bureaucracy per year between 1995 and 2000 (Cavalcante and Carvalho Reference Cavalcante and Carvalho2017, 9). Moreover, public entrance exams to hire experts into social sector bureaucracies, as traditional civil servants, were not created until 2010, and those exams were attached to only 825 open positions (Souza Reference Souza2017, 11–2).

Likewise, evidence suggests that many agency directors used international organizations to help them avoid government procurement regulations. According to United Nations data, the UN managed an average of 108.8 million US dollars of procurement for goods and services annually in Brazil between 1999 and 2010.Footnote 25 As one auditor explained, expressing the same logic I heard from other bureaucrats, “the bureaucracy involved in [international organizations] is less than in government. There are always fewer steps for executing a budget expense.”Footnote 26 Another auditor emphasized that Brazil was not using international organizations for their financial resources. In his words, “you are transferring resources to those organizations to facilitate [government expenditures].Footnote 27

To make a strong case that bureaucratic outsourcing helped agency directors build capable government programs, we would ideally seek employee performance evaluations and budget execution data. However, such government data on outsourced bureaucracies is relatively unavailable because of factors such as the removal of outsourced programs from accounting records and the limited reach of government auditors. (These reasons are further explained in Appendix C.)

However, qualitative evidence suggests that outsourcing did help to build capable government programs, at least in the short term. A 2001 audit of UNESCO’s Brazil operations is particularly revealing because it was conducted by investigators who sought to uncover corruption. The evaluation concluded, contrary to the investigators’ suspicion, that UNESCO involvement in Brazil had brought positive outcomes for bureaucratic capacity. According to the report,

the [UNESCO] Office has been successful in attracting highly qualified and well-respected experts and programme staff. [.…] We also observed when visiting Ministries and Agencies that UNESCO staff and in particular programme coordinators were well known and respected. (Stern and Defourny Reference Stern and Defourny2001)

Similarly, an evaluation of UNDP’s Brazil operations from 2002 to 20l1 concludes,

the Government boosted its capacities, increasing its technical staff and strengthening the bureaucracy. In this sense, the fact that the Government gained strength in strategic areas should be interpreted as a positive result of UNDP’s action over the last decade.

All of my interviewees, including external auditors, agreed that bureaucratic outsourcing had helped agencies execute their budgets by avoiding burdensome procurement regulations. Even the very government auditors who were cracking down on the practice agreed that “bureaucratic outsourcing has brought benefits for society.”Footnote 28

Vulnerabilities of the Outsourcing Approach

This section discusses two vulnerabilities of the outsourcing approach. The first vulnerability is the potential for clientelism and corruption. However, in Brazil interviews and external evaluations did not suggest that going around government accountability rules gave rise to widespread corruption or clientelism. As I described in the previous section, the bureaucrats who were selectively hired as UN consultants were widely viewed as highly capable bureaucrats who were deeply committed to their agencies’ goals. At the same time, these programs were built in a particular context of broad political commitment to building effective national social policies. In other contexts, where agency directors have explicitly partisan or personalistic goals, they could use nonstate organizations as vehicles as help them garner political favors.

A second vulnerability is the long-term potential for political intervention and subversion. Outsourced bureaucracies are not institutionalized public sector agencies; they are therefore less vulnerable to short-term political interference. Yet their existence may ultimately be more precarious. Once a technical cooperation project is underway and funding has been transferred to a United Nations account, politicians cannot easily interfere with it. After technical cooperation agreements expire, however, these programs may be dismantled more easily than institutionalized government programs.

After the ultra-right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro took over the presidency in 2019, with an agenda to dismantle environmental and human rights programs, the advantages and vulnerabilities of bypass strategies for building “shadow” state capacity became more salient. On the one hand, preliminary evidence suggests that Bolsa Família and the AIDS program suffered less from Bolsonaro’s attacks on bureaucracy than other government programs did. On the other hand, the vulnerabilities of outsourcing are brought into relief if we look back to the fate of Brazil’s first pockets of effectiveness, created through authoritarian methods of parallel administration in the 1950s. As Barbara Geddes describes, “none was able to protect itself from political intervention when presidential support was withdrawn” (Reference Geddes1990, 231).

Conclusion

This article has made two main contributions. First, it has shed light on underexplored drawbacks of accountability initiatives targeted at fighting corruption. By tracing the development of two capable bureaucracies in the wake of accountability reforms, I show how the very mechanisms that limit opportunities for government misbehavior can also limit opportunities for building bureaucratic capacity. Second, this article has revealed a hidden strategy used by modern-day policy makers to bypass accountability rules: bureaucratic outsourcing. Counterintuitively, hypothesis-building evidence from Brazil suggests public servants who care about policy improvement may escape accountability rules to build innovative and effective programs. But by extension, this article also implies that policy makers could use bureaucratic outsourcing for partisan or personalistic uses, with negative outcomes for bureaucratic capacity.

This theoretical framework raises important new issues for scholars of institutional weakness and change as well as for scholars of public sector reform. As others have noted, the origins of an institution can have lasting effects (Mayka Reference Mayka2019). In this hypothesis-generating article, I demonstrated that bureaucratic outsourcing is one path to creating capable programs in inhospitable public sector environments—building what I call shadow state capacity. Yet my findings also suggest that bypassing accountability rules is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for producing effective bureaucracies and, moreover, that it may introduce new vulnerabilities for fledgling government programs. This article thus calls for a research agenda that explores variation in the motivations that drive policy makers to outsource bureaucracies as strategy for escaping accountability rules, in the national legal frameworks that govern bureaucratic outsourcing and, more broadly, in the conditions under which outsourced agencies institutionalize into capable government bureaucracies.

This research agenda has important normative implications. Developing countries commonly suffer from weak public sector institutions (Brinks, Levitsky, and Murillo Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2019; Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017). At the same time, large numbers of new government programs have been created to serve marginalized groups during the last 30 years. Answering the underexplored question of how to construct new institutions that work well, and that survive over time, is essential for fighting poverty and promoting social justice across the world.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000892.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the anonymous reviewers who helped me polish this article through constructive but rigorous criticism. Thanks as well to the following people for feedback on various iterations of the paper: Santiago Anria, Katherine Bersch, Emily Clough, Ruth Berins Collier, Kent Eaton, Romain Ferrali, Jonathan Fox, Candelaria Garay, Yanilda González, Gus Greenstein, Kathryn Hochstetler, Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner, Jody LaPorte, Benjamin Lessing, Lindsay Mayka, Jami Nelson-Nuñez, Ezequiel González Ocantos, Marília Oliveira, Brian Palmer-Rubin, Alison Post, Philip Rocco, Duane Swank, Guillermo Toral, the participants of the 2018 SWMMR workshop, and the participants of Repal 2019. Liam Bower provided outstanding research assistance.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by generous support from the Center for Peace Studies and the Office of International Education at Marquette University.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Marquette University, as study HR-3435 (included as Appendix E). The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.