Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

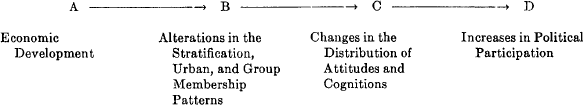

Mass political participation increases as nations become more economically developed. In Part I of this study we attempted to identify the significant social experiences which explain the high levels of participation in economically developed nations. We formulated and explored the following general theory:

Economic development alters the social structure of a nation. As nations become more economically developed, three major changes occur: (1) the relative size of the upper and middle classes becomes greater; (2) larger numbers of citizens are concentrated in the urban areas; and (3) the density and complexity of economic and secondary organizations increases. These social changes imply political changes. Greater proportions of the population find themselves in life situations which lead to increased political information, political awareness, sense of personal political efficacy, and other relevant attitudes. These attitude changes, in turn, lead to increases in political participation.

The theory can be presented schematically in the following form:

We were able to demonstrate that individuals' levels of social status and organizational involvement were strongly and consistently related to their levels of political participation. The survey data from five nations showed, further, that organizational involvement was more strongly related to participation, and more consistently from nation to nation, than was social status.

The authors are listed alphabetically to indicate equal coauthorship.

Various institutions and individuals have been of considerable help to the authors in the preparation of this research. The department of Political Science, Washington University, provided summer support to two of the authors at an early stage of data preparation. Under NSF grants, the computation centers at both Washington University and Stanford University made machine time available. The facilities and the personnel of the Stanford Institute of Political Studies, particularly Mr. C. Hadlai Hull, the Institute's computer consultant, were invaluable aids to the completion of this research. The Department of Political Science of the University of California, Berkeley, provided funds to help us prepare the final draft for publication. For critical comments we are indebted to many readers, in particular to Sidney Verba, Hayward R. Alker, and Duncan MacRae, as well as to Warren E. Miller, who, as a referee for the REview, made a major contribution to the current version of the paper. Other, more specific, debts are acknowledged below. Part I appeared in this Review, 63, (June, 1969).

1 See our “Social Structure and Political Participation, I,” Appendix B, this Review, 63 (06, 1969)Google Scholar, for the multiple item scales used to test these relationships. Social status includes individual's education, income, occupation, and an interviewer estimate. Organizational involvement includes primarily number of organizational memberships and having held an office in an organization. Participation includes talking politics, contacting local officials, contacting national officials, and joining formal political parties or organizations—but not voting.

2 The survey data are taken from the Almond-Verba Five-Nation Study. The five nations represented are Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, Mexico and Italy. See Almond, Gabriel A. and Verba, Sidney, The Civic Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, for information on samples and survey design. See Part I of this study, this Review, 63 (June, 1969), for an extended discussion of methodological issues related to how we processed these data.

3 The size of community in which a citizen lives is negatively related to his local political participation level. However, this negative relationship is not sufficiently strong (it explains less than two percent of the variance in local participation) to account for the absence of any relationship between place of residence and general political participation. We concluded that although urbanization is a major part of economic development, it is not, even in part, responsible for great increases in mass political participation.

4 For example, see Blalock, Hubert, “Causal Inferences, Closed Populations, and Measures of Association,” this Review, 61 (03, 1967), 130–136 Google Scholar; Blalock, Hubert M., Causal Inferences in Non-Experimental Research (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964)Google Scholar; Miller, Warren E. and Stokes, Donald E., “Constituency Influence in Congress,” this Review, 57 (03, 1963), 45–56 Google Scholar; Goldberg, Arthur S., “Discerning a Causal Pattern among Data on Voting Behavior,” this Review, 60 (12, 1966), 913–933 Google Scholar; and McCrone, Donald J. and Cnudde, Charles F., “Towards a Communications Theory of Democratic Development,” this Review, 61 (03, 1967), 72–79 Google Scholar. We owe a particular debt to the excellent discussion by Alker, Hayward R. Jr., “Causal Inferences and Political Analysis,” in Bernd, Joseph (ed.), Mathematical Applications in Political Science II (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1966), pp. 7–43 Google Scholar.

5 Duncan, Otis Dudley, “Path Analysis: Sociological Examples,” American Journal of Sociology, 72 (07, 1966), 6–7 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

6 These path coefficients are the standardized B (slope) coefficients for a series of regression equations. The causal model is described by these simultaneous equations. The causal properties are linked to the fact that each succeeding equation adds a new variable to the model—and is described as a dependent variable “caused” by all preceding variables in the model, but by none of the ones subsequently added. The final dependent variable, participation in this case, is the product of all other variables. All equations after the first two (X2 = B21 X1 + B2t Rt, and X1 = B18, R8) are shown in the left hand column in Table 2. As Blalock, op. cit., has suggested, unstandardized b weights provide rich interpretations that these standardized path coefficients do not. However, the scores obtained on the variables in our model are based in many cases on originally arbitrary variances. The different questions on competence, for example, had different numbers of alternative responses and even the meaningfulness of the zero points is not clear on an attitude variable of this type. In this situation the interpretation of the unstandardized scores is clearly very difficult. See the comments by Tukey, John W., in “Causations, Regression, and Path Analysis,” in Kempthorne, Oscar, et al. (eds.), Statistics and Mathematics in Biology (Ames, Iowa: Iowa State College Press, 1954)Google Scholar. However, we do hope to examine unstandardized coefficients in models involving non-attitudinal variables only, particularly in regard to the lines of inquiry raised in the section on “Social Structure and the Participation of Class Groups,” below, in future analysis.

7 For a more complete discussion of these limitations see Alker, op. cit.; Duncan, op. cit.; Boudon, Raymond, “A Method of Linear Causal Analysis: Dependence Analysis,” American Sociological Review, 30 (06, 1965), 365–374 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Forbes, Hugh Donald and Tufte, Edward R., “A Note of Caution in Causal Modelling,” this Review, 62 (12, 1968), 1258–1264 Google Scholar. Although the useful Forbes and Tufte discussion was not available to us while this analysis was being conducted, we believe that our approach to causal modelling avoids many of the problems raised by them. We must continue to emphasize, of course, that the causal order of our variables is posited from deductive theory, not derived from the data.

8 Urbanization has been deleted as a variable in the model, since we know it to be significantly related to Social Status only, of all the variables in the model, and its deletion greatly simplifies calculation of paths. Deletion of urbanization is a violation of this assumption, in a minor fashion, when considering local participation only, rather than combined scales. It is therefore reintroduced below when considering the causal models of local and national participation separately.

9 Nonrecursive path analysis is also possible. At a future point we hope to explore further interactive models for this and similar data. We have not yet moved to this stage of analysis. See Duncan, op. cit.

10 In the eight variable causal model there are 54 paths from status to participation. No paths moving back along the model at any point are allowed by the constraints imposed.

11 At an earlier stage in the analysis, scales were built with consistency checks on the SES dimension. Persons high on one status item and very low on another were deleted. This procedure increased correlations, but decreased the size of the valid sample, and was not, therefore, used in this analysis. It is especially noteworthy that while only about 10% of the original samples in the US, UK, Italy, and Mexico failed to meet the SES dimension consistency check, about 50% of the German sample failed to meet it. This suggests the disruption of the social stratification system in Germany as a consequence, no doubt, of the historical upheavals. The strong wage position of workers in the post-war boom, following the leveling impact of World War II and the Third Reich, may also be a contributing factor. See the comments by Edinger, Lewis J., Politics in Germany (Boston: Little, Brown, 1968), pp. 19–30 Google Scholar.

12 This research, carried out by Sidney Verba and Norman Nie, shows that a great majority of all types of voluntary organizations in the U.S. have an interest in public affairs and members engage in political discussions; this accounts for the strong relationship between organizational involvement and participation even when not controlling for the type of organization. These findings are based on preliminary analysis of the U.S. data from the “Cross National Research Program in Social and Political Change.”

13 As is described in Almond, Gabriel and Verba, Sidney, The Civic Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), pp. 509–525 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, the national samples were cluster samples and collected in somewhat different ways with different degrees of success. In Mexico, as noted, no interviews were collected in towns under 10,000. Given these differences and the fact that much of the sampling data was not available in our analysis tapes, we have not attempted to compute a sampling error— it could only be a guess—and prefer to rely on the strength and consistency of relationships, rather than significance tests presuming probability samples. See the comments on significance of correlation coefficients in Part I, Table 1, this Review, 63 (June, 1969).

14 See Duncan, op. cit.

15 See Almond and Verba, op. cit., pp. 161–179; and Campbell, Angus, Converse, Philip E., Miller, Warren E., and Stokes, Donald E., The American Voter (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1960), pp. 105–106 Google Scholar. For a general review, see Dawson, Richard and Prewitt, Kenneth, Political Socialization (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1969), especially chapters 9 and 10Google Scholar.

16 Alker, op. cit.; Deutsch, Karl W., “Social Mobilization and Political Development,” this Review, 55 (09, 1961), 493–514 Google Scholar; Lerner, Daniel, The Passing of Traditional Society (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1958)Google Scholar; and see the essays in Pye, Lucian W. (ed.) Communication and Political Development (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963)Google Scholar. It should be emphasized, however, that we are here dealing with very fundamental types of information, as captured by these responses naming party leaders and cabinet positions at the national levels. More detailed and sophisticated types of information might be expected to follow such factors as involvement and participation, rather than act as a basis for them.

17 As noted in Part I, footnote 15, efficacy is not a simple concept and other dimensions of it must be explored in other analysis. Efficacy as measured here is a sense of personal ability to cope with the political world. It seems to be a somewhat different concept from sense of approval or satisfaction that the political system is generally responsive.

18 See Key, V. O., Public Opinion and American Democracy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961)Google Scholar; and also Almond, Gabriel A., The American People and Foreign Policy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954)Google Scholar.

19 Carrying out the equivalent operation for participation in national politics yields even less distinctive patterns. Direct linkages between place of residence and contacting national officials are virtually zero in each nation; the basic interactive patterns analyzed in the general model are still the overwhelming ones; only sense of national efficacy shows a significant—and still very slight—positive relationship to living in larger cities (and only in three nations of our five). The effect of urban residence on patterns of contacting national officials, in other words, is possibly measurable, but very, very weak. No more than one percent of the variance in the national participation item is affected by urban residence in any of the five nations.

20 We are indebted to Mr. Jae-On Kim for help with some of the methodology required for our analysis in this section.

21 It may also be true that the development of different types of national industries may create differential needs for economic organizations depending upon industry requirements to coordinate production, transportation, marketing and the like. See, for example, Barrington Moore, Jr.'s discussion of the differential impact that varying types of national industry have on the social structure, in Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966)Google Scholar.

23 See for interpretation of percentage differences, Somers, Robert H., “A New Asymmetric Measure of Ordinal Variables,” American Sociological Review, 27 (1962), 799–811 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Also for interpretation of percentages for 2 × 2 tables as “proportional reduction of error” comparable in meaning to the square of the product moment r, see Jae-On Kim, “Predictive Measures of Ordinal Association;” unpublished manuscript. We are also indebted to Mr. Kim for helping us work out these percentage differences in our data.

23 Note how closely these projective estimates come to the actual data presented in Table 4 Part I of this article.

24 The need for caution in moving from analysis of social stratification, and even gross patterns of political participation, to assumptions about political decision-making patterns and outcomes has been amply demonstrated in the various studies of community power. See especially Dahl, Robert, Who Governs? (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961)Google Scholar; and Polsby, Nelson W., Community Power and Political Theory, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963)Google Scholar. Factors shaping participation patterns must be incorporated as one element in such analysis.

25 Since our scales were derived to give intranation distributions of maximum utility, their validity for cross-national absolute comparisons is somewhat limited. Nor is it entirely clear how one should treat an indicator like “years of education” as a social status indicator on a cross-national basis. The meaning of such absolute measures, like involve the real buying power of formal income equivalents, depends considerably on the distribution of the commodity within the society. Nonetheless, the chosen cutting points fitted four of the societies in fairly plausible fashion. Actual distribution of education in the United States, for example, reported in the 1959 census was about 17% college educated, 48% 9–12 years of education, and 35% with 8 years or less. (Compare the class distribution in Table 6.) Only in Britain was a slightly different scale cutting point used—the division between lower and middle class was lowered by one level to show 46% in the lower class rather than 60%. This seemed a more plausible distribution in comparable terms, although it does not greatly affect the class analysis.

26 Lipset, Seymour M. and Rokkan, Stein, Party Systems and Voter Alignments (New York: Free Press, 1967), pp. 50–56 Google Scholar.

27 A wide range of possible reasons for this failure of group mobilization of the American lower classes has been suggested. These include the presence of the frontier, the general belief in social mobility and economic progress, the tremendous linguistic, ethnic, and religious differences during the period of immigrations, and the lack of traditional social structures such as guilds. Others have suggested more specifically political factors. For example, Walter Burnham, Dean, “The Changing Shape of the American Political Universe,” this Review, 59 (03, 1965), p. 24 Google Scholar. A unified interpretation is obviously beyond the scope of the present discussion.

28 Olson, Mancur, The Logic of Collective Action (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965)Google Scholar. The organizational membership cutting points are the same from nation to nation; they correspond closely to the percentage of citizens in each nation reporting membership in one or more organizations (U.S. 57%; U.K. 47%; Germany 44%; Italy 30%; Mexico 24%), although our scale is composed of several items, rather than membership alone.

29 Orum, Anthony M., “A Reappraisal of Social and Political Participation of Negroes,” American Journal of Sociology, 72 (07, 1966), 32–46 CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

30 For example, Lipset, Seymour Martin, Political Man (Garden City: Doubleday and Co., 1960), pp. 27–63 Google Scholar. Also see Cutwright, Philip, “National Political Development,” in Polsby, Nelson W., Dentler, Robert A., and Smith, Paul L., (eds.), Politics and Social Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1963), pp. 569–582 Google Scholar. In his critical analysis of Lipset and Cutwright, Deane Neubauer argues that economic development may be a necessary condition for democracy, at least to some threshold, but that the relationship is not linear, and does not seem to hold within the subset of more developed systems he examines. See Neubauer, Deane, “Some Conditions of Democracy,” this Review, 61 (12, 1967), pp. 1002–1009 Google Scholar.

31 Dahl, Robert A., A Preface to Democratic Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956)Google Scholar; Key, op. cit.; and see the exchange between Jack Walker, “A Critique of the Elitist Theory of Democracy,” and Dahl, Robert A., “Further Reflections on the ‘Elitist Theory of Democracy,’” this Review, 60 (06, 1966), 285–305 Google Scholar, and Communications to the Editor.

32 Olson, op. cit.

33 Dahl, op. cit.; and Key., op. cit.

34 Prothro, James W. and Grigg, Charles M., “Fundamental Principles of Democracy,” Journal of Politics, 22 (1960), 276–294 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Stouffer, Samuel, Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1955)Google Scholar; McClosky, Herbert, Hoffmann, Paul J., and O'Hara, Rosemary, “Issue Conflict and Consensus among Party Leaders and Followers,” this Review, 59 (06, 1960), 406–427 Google Scholar.

35 See, for example, MacRae, Duncan Jr., Parliament, Parties and Society in France, 1946-1958 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1967.)Google Scholar Also, for suggestive data from a single community, Powell, G. Bingham Jr., Fragmentation and Hostility in an Austrian Community (Stanford: Stanford University Press, forthcoming)Google Scholar.

36 See the general discussion of organizational fragmentation; as well as the data on Italy, in Verba, Sidney, “Organizational Membership and Democratic Consensus,” Journal of Politics, 27 (1965), 467–497 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Also see the discussion and data of Powell, ibid.; Chapters I and IV; Lijphart, Arend, The Politics of Accommodation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, Chapter I; and Rodney P. Stiefbold, “Elite-Mass Opinion Structure and Communication Flow in a Consociational Democracy (Austria),” paper presented at the 1968 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.