The emergence of complex societies poses a challenge for archaeologists (Kintigh et al. Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler, Limp, Maschner, Michener, Pauketat, Peregrine, Sabloff, Wilkinson, Wright and Zeder2014). Traditional approaches assume that sociopolitical groups grow within an existing conceptual framework. Maine (Reference Maine1861) famously suggested that ancient people expanded kin relations to fictitiously include nonkin. Kin-based communities eventually transformed into impersonal societies (Durkheim Reference Durkheim and Halls1984; Tönnies Reference Tönnies1887; Weber Reference Weber, Fischoff, Gerth, Henderson, Kolegar, Mills, Parsons, Rheinstein, Roth, Shils and Wittich1968). Scholars have critiqued the evolutionary ladders of these models (e.g., Pauketat Reference Pauketat2007; Smith Reference Smith2003). To form larger social groups, people recognize others as members of the same community. Based on Husserl's concept of empathy, we discuss how earlier models merge—erroneously in our opinion—similarity with sameness. We argue that community formation makes the shared identity salient without resolving differences. In the politics of belonging, people's perceptions and practices broaden to create a shared spatiotemporal framework. At the same time, their increased social interactions lay bare power differences. Building public architecture as a group materializes the shared vision of community as well as differential individual contributions.

Our case study is Dos Ceibas in the Maya Lowlands (Figure 1). Founded between 350 b.c. and a.d. 250, Dos Ceibas exemplifies Preclassic sociopolitical changes in the Petexbatun region. Extensive investigations allow us to reconstruct the Late Preclassic hamlet below the Late Classic (a.d. 600–800) village. It likely consisted of two residential groups. We show that Dos Ceibas's residents transformed one group's possible shrine into a small pyramid overlooking a large plaza. The new center differentiated the hamlet's inhabitants. Kinship and alliance models predict a horizontal expansion, with the descendants of the founders adding new households. Dos Ceibas's vertical Preclassic development differs, and we argue that it exemplifies the emergence of community as new subjectivity.

Figure 1. Map of the site of Dos Ceibas. Upper left inset map shows its location in the southwestern Maya Lowlands; lower right inset shows its location in the Petexbatun region (bolded sites have Preclassic predecessors); blue circles mark groups that were investigated. Eberl maps.

Empathy and the politics of belonging

To include others, individuals are traditionally assumed to stretch existing mechanisms and kinship in particular. In Maine's (Reference Maine1861) famous model, descent unifies families and larger social groups; as the latter grow, people complement real kin relations with “fictitious extensions of consanguinity” (Maine Reference Maine1861:132). In the following, we argue that people develop a new understanding of themselves and others as they form a community. We discuss Husserl's concept of Einfühlung, or “empathy.” Feeling and being similar differ. People not only recognize differences but also negotiate them. This dimension is absent in Husserl and, correspondingly, we emphasize the politics of belonging.

Our argument builds on theories of agency and practice. Ethnographers have deconstructed the factuality of kinship (e.g., Carsten Reference Carsten2000; Godelier Reference Godelier and Scott2011; Sahlins Reference Sahlins2013). In Lévi-Strauss's (Reference Lévi-Strauss and Modelski1982, Reference Lévi-Strauss and Willis1987) house model, descent and affinity “do not construct or define the house as social group, they follow from it” (Marshall Reference Marshall, Joyce and Gillespie2000:75). House members engage in diverse social relations and employ the language of kinship to maintain cohesion. Following this lead, archaeologists have moved to “more practice-based understandings of how kin and kin-like relationships are strategically operationalized and understood by the persons who enact them” (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2000b:478; also Bentley Reference Bentley2022; Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Joyce and Gillespie2000a). Leaders enjoy a privileged role in steering these narratives, but they seldom have the absolute power to do so alone. Nonelite individuals, households, lineages, and other groups cooperate, negotiate, and take collective action (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008; Carballo and Feinman Reference Carballo and Feinman2016; Fargher and Heredia Espinoza Reference Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016; Feinman and Carballo Reference Feinman and Carballo2018; Halperin Reference Halperin2017; Jennings and Earle Reference Jennings and Earle2016). Monumental building projects that in the past were seen as evidence for emerging leaders (e.g., Blake Reference Blake and Fowler1991) require labor input from a larger social group (Trigger Reference Trigger1990) and often turn out to be communal efforts (Joyce Reference Joyce2004; Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Dobres and Robb2000).

Shared group identities are no longer assumed to be the automatic outcome of kin relations. Watanabe (Reference Watanabe1992:ix) identifies community as a “locus of contingent social cooperation involving diverse—at times divergent—individual interests.” To create a meaningfully bounded place, individuals participate in, commit to, and invest in locally relevant discourses (Watanabe Reference Watanabe1992:15). From Anderson's (Reference Anderson2006) perspective, individuals may not relate or even know each other. Instead, shared modes of apprehending the world allow them to imagine others as members of the same community. Although designed to explain the rise of modern nation states, Anderson's model has inspired studies of imagined communities in ancient societies (Canuto and Yaeger Reference Canuto and Yaeger2000).

Similarity should not be confused with sameness. Husserl (Reference Husserl and Cairns1960) discusses how trading places enables people to understand the perspectives of others (Eberl Reference Eberl2017:39–41). Individuals observe each other and sometimes (e.g., when standing in line) even literally step into someone else's shoes. However fleetingly, ego is alter ego for the other (Husserl Reference Husserl and Cairns1969:237–238). Experiencing other subjects’ bodies and behaviors inspires empathy (Hermberg Reference Hermberg2006:34). It serves as “ontological bridge from one's own subject, which is given proximally alone, to the other subject, which is proximally quite closed off” (Heidegger Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson1962:162). For Heidegger, this reduces the other to publicly perceptible attributes and therefore to a mere clone of the self: “Everyone is the other, and no one is himself” (Heidegger Reference Heidegger, Macquarrie and Robinson1962:162). However, Husserl carefully distinguishes between object and representation. Individuals perceive other subjects in terms of bodies and behavior, but they cannot experience their “psychic contents with actual originality” (Husserl Reference Husserl and Cairns1969:239). The constitution of others must, therefore, as Husserl concludes, be different from that of one's own psychophysical Ego (also Hermberg Reference Hermberg2006:38; Sartre Reference Sartre1939:129). Empathy makes the other salient but not the same.

Belonging is an affectional and rationalizable process directed at others. Husserl's German term for empathy—Einfühlung—consists of two parts. The term fühlen, or “sensing,” points to a perceptual and emotional process that is, as ein- or “into” specifies, located in relations among individuals. Given that their affectional dimension is often tacit, community identities can be very powerful. The salient recognition of others originates in part from shared practices and regular face-to-face contacts that foster trust and cooperation (Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2013; Munson and Pinzón Reference Munson and Pinzón2017; Yaeger and Canuto Reference Yaeger, Canuto, Canuto and Yaeger2000). Nonetheless, at least some people develop a “theoretical attitude” to question what they take for granted (Husserl Reference Husserl and Carr1970:281, Reference Husserl, Rojcewicz and Schuwer1989:7; see also Hermberg Reference Hermberg2006:32–39).

Husserl (Reference Husserl and Carr1970:26) pits the perception-based natural and representation-based theoretical attitude against each other. He solves the tension by arguing that people should break with their habits, enlighten themselves, and adopt the theoretical attitude. People reorient themselves to make the world in which they live—and that they usually take for granted—into the object of their thoughts (Duranti Reference Duranti2010:27). Derrida (Reference Derrida and Lawlor2011:42, 71–75) criticizes Husserl for dichotomizing fact versus representation (see also Andrews Reference Andrews and Tymieniecka2004). He proposes a dialectical process called différance, which consists of differentiation and deferral (Derrida Reference Derrida and Lawlor2011:75). Differentiation refers to the establishing a dichotomy like Husserl's fact versus representation. Swinging back and forth like a pendulum between extremes without ever reaching them, this process is never-ending and defers finalization. For us, perception and cognition are mutually linked. We employ Derrida's (Reference Derrida and Lawlor2011) différance to argue for a co-constitutive process (Eberl Reference Eberl2017:103–104). Empathy rests on ongoing social interactions that reveal similarities and differences among community members (Eberl Reference Eberl2014).

People may feel empathy for others tacitly; yet, at least some become aware of it and use it strategically. Similar to the anthropological re-evaluation of kinship (see above), we argue that empathy is not an essential or universal feature of being human. Instead, empathy is essentialized in context-specific ways. We emphasize ways to point to diverse possibilities that may overlap and resonate or that may be authorized and become dominant (Bourdieu's [Reference Bourdieu1977:39–43] “officializing strategy”). We hesitate to call this the “Language of Empathy” and identify it as a Foucauldian discourse, though. Empathy can be verbalized, but it is often tacit. In addition, its power derives at least in part from materialization and embodiment.

The politics of belonging raises three issues for community formation that we discuss further below. First, belonging reflects an at least partially public process during which people observe each other. We argue that individuals materialize their community. Trading places allows people to step into the someone else's shoes. They create intersubjective understandings through an embodied process (Duranti Reference Duranti2010). Second, communities should not be mistaken for homogeneous social groups (Blackmore Reference Blackmore2011; Eberl Reference Eberl2014; Ensor Reference Ensor2013a, Reference Ensor2013b; Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Joyce and Gillespie2000a; Joyce and Gillespie Reference Joyce and Gillespie2000). Close social interactions make community members familiar with each other not only as role-playing persons but also as unique individuals. At least some people become aware of what they share and what sets them apart in contextualized ways. Third, belonging requires the continual negotiation of community. During bordering, people reach outward and identify differences; during bonding, people look inward and constitute sameness. Both processes complement each other and essentialize sameness.

Late Preclassic farming communities in the Petexbatun region

Community requires a different understanding of belonging. We study the three issues raised above in the Petexbatun region during the Late Preclassic (Figure 1). From our theoretical perspective, community originates in a perceptual but politicized basis; its specific form varies and depends on historical and cultural context. Correspondingly, our model allows for different subjectivities. We focus on farming communities, but this does not mean that people had no communities before. Since at least Flannery's (Reference Flannery1970:23–24) discussion of Gheo-Shih, scholars have argued for Archaic-period communities in Mesoamerica (for recent reviews see Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, Stemp, Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021; Lohse Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig and Smith2019). At Aguada Fénix, Preclassic peoples built a monumental platform that presumably allowed them to gather and possibly create a shared identity (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Vázquez López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Méndez Bauer, García Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020). Who these people were and how they self-identified is open for discussion (for a critique of Göbekli Tepe as uninhabited ceremonial center see Clare Reference Clare2020:83–84). In Mesoamerica, foragers seem to have coexisted with incipient farmers for millennia (see reviews above and Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Sharpe, Palomo, Pinzón, Nasu, Triadan, Culleton and Kennett2022). In addition, scholars increasingly question the farmer-versus-forager and permanent-versus-mobile dichotomies (Walker Reference Walker2023).

In the Petexbatun region, people built an acropolis at Punta de Chimino during the seventh century b.c., long after the ceremonial center at nearby Ceibal (Bachand Reference Bachand2006; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013). By 350 b.c., settlements are attested at Aguateca, Punta de Chimino, and Bayak (see lower right inset in Figure 1; Bachand Reference Bachand2006; Inomata Reference Inomata2008:129–136; O'Mansky Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Escobedo and O'Mansky1996; O'Mansky et al. Reference O'Mansky, Hinson, Wheat, Sunahara, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994; Van Tuerenhout et al. Reference Van Tuerenhout, Henderson, Maslyk, Wheat, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993; for Preclassic sites in the Pasion River valley see Johnston Reference Johnston2006; Munson and Pinzón Reference Munson and Pinzón2017; Willey Reference Willey1973). We add the site of Dos Ceibas. Our investigations complement the earlier focus on monumental Preclassic buildings and reveal a Preclassic hamlet.

The site of Dos Ceibas was discovered during the systematic survey of the hinterland south of the royal capital of Aguateca (Eberl Reference Eberl2014:68–74). The 1.8 km long and 0.2 km wide survey followed the top of the crescent-shaped escarpment that rises 40 m above wetlands to the east (lower right inset in Figure 1). Dos Ceibas's residential groups and public architecture occupy the highest points near the escarpment. They consist of 131 structures in 33 patio groups (Figure 1; Eberl Reference Eberl2014:79). The residential groups cluster around a ceremonial complex (the North Plaza) and the largest residential group (the South Plaza). Our survey likely covered most of Dos Ceibas, because the area to the west floods during the rainy season and becomes a marsh. Environmental conditions are less than ideal. Forays to the east and west of the survey area located the site's only permanent water source at the foot of the escarpment. The spring is shallow and outputs a few liters per minute—too little to sustain a settlement. Dos Ceibas's inhabitants likely had to obtain water from springs at Nacimiento and Aguateca. The black soils of the horst upland are on average only 0.22 m deep and less fertile than those farther south (Eberl Reference Eberl2014:17–18).

Our survey initiated a comprehensive investigation of Dos Ceibas (Eberl Reference Eberl2014:179–221; Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, Corado, Vela González, Inomata, Triadan, Guerra Ruiz and Seijas2009). We excavated 43 test pits and two buildings extensively. In addition, we cleared, documented, and then backfilled 10 looted buildings. Twenty-five, or 75.8 percent, of all groups were studied to expose architecture, construction history, and associated middens.

The settlement history of Dos Ceibas begins around 350 b.c., pauses during the Early Classic period, and ends in the eighth century a.d. Its visible architecture and about 90 percent of all ceramic sherds date to the Late Classic period (Table 1). Roughly 10 percent are Preclassic Faisan Chicanel ceramics from the unslipped Zapote ceramic group and the Paso Caballo Waxy ware (Figures 2 and 7 [inset]). The latter were slipped red (e.g., Sierra Red and Laguna Verde Incised), cream (Flor Cream), and black (Polvero Black). We encountered no Early Classic construction activity, and Early Classic sherds appear only mixed into Late Classic contexts (Eberl Reference Eberl2014:219). Dos Ceibas was most likely abandoned between a.d. 250 and 600 .

Table 1. Chronological distribution of ceramic sherds at Dos Ceibas (Eberl table).a

a Ceramic classification and periods based on Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop2013; Inomata Reference Inomata, Inomata and Triadan2010. The absolute chronology takes into account roughly 200 radiocarbon dates from Ceibal.

b The 36 Middle Preclassic sherds are mixed into later deposits and construction levels. The most common types are Baldizon, Joventud, Pital, and Chunhinta. In some cases, ceramic traits continue from the Middle to the Late Preclassic periods.

Figure 2. Preclassic sherds from Dos Ceibas—all from the North Plaza except (c) and (d) (Eberl drawings): (a) Zapote Punctuated jar sherd; (b) Zapote Impressed sherd; (c) Polvero Black sherd from Group MP31; (d) Polvero Black sherd from Group MP16; (e) Guitara Incised sherd; (f, g) Laguna Verde Incised sherds; (h) Laguna Verde jar fragment; (i) Partial Sierra Red dish.

The Late Preclassic settlement was limited to Dos Ceibas's later center. Construction evidence that we discuss below revealed Preclassic buildings below the North Group and Group MP16 (Figure 3). Our investigations did not include Structure R27-65, a few meters east of these two groups. Its amorphous squarish shape differs from Late Classic mounds elsewhere and suggests another Preclassic building. Preclassic ceramic sherds concentrate similarly in the center. They make up more than half of all datable sherds in the North Plaza and more than a quarter of all datable sherds in Group MP16 (Figure 4; Supplemental Text 1). Frequencies drop sharply outside of the center. After removing groups with low sherd totals, the North Plaza and Group MP16 remain the only groups with a substantial number of Faisan Chicanel sherds and Preclassic constructions.

Figure 3. Investigations in Dos Ceibas's center (Eberl map and digitized profile drawings by Omar Schwendener; colors approximate the Munsell Color that was measured in the field as closely as possible; in cases with similarly colored levels, however, we varied transparency to increase the contrasts between individual levels): (a) Map of the North Plaza and Group MP16 (light gray areas indicate looters’ pits; test pit ST8B in Structure R27-69 produced no Preclassic construction levels; test pit ST29C in Structure R27-61 was only excavated to the original floor); (b) South profile of test pit ST8A into the center of North Plaza's platform (field drawing by P. Rodas); (c) East profile of test pit ST8E into Structure R27-67; (d) South profile of cleared looter's pit ST29A into Structure R27-57; (e) East profile of test pit ST29B into the plaza of Dos Ceibas Group MP16 (field drawing by C. Vela).

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of Preclassic sherd frequencies at Dos Ceibas (each data point summarizes the investigations in a group; the nearby site of Cerro de Cheyo is shown for comparative purposes; Eberl diagram).

Emplacing community

For Husserl (Reference Husserl and Cairns1960), trading places is crucial to develop empathy. Above, we use his concept as a theoretical basis to discuss community. To step into another's shoes is an embodied process. Archaeologists have linked architecture and shared identity (e.g., Guengerich Reference Guengerich2017; Joyce Reference Joyce2004; Marcus Reference Marcus, Papadopoulos and Leventhal2003; Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Dobres and Robb2000; Trigger Reference Trigger1990). The process of building brings people together, both practically and metaphorically. As a public event, individuals not only work with but also observe each other. Their participation signals but not necessarily reflects inner motivations. Materiality is ambivalent and leaves intended meanings undefined. We stress its ability to make community salient. We speak of emplacing community to refer to diachronic material practices through which people create and maintain a particular place (see also Cobb Reference Cobb2005:764). Our investigations allow us to reconstruct Dos Ceibas's Preclassic settlement below the North Plaza and Group MP16 (Figure 3). In the latter, we excavated three looted buildings and the plaza.

To build Group MP16, Late Preclassic people dug yellow-brown clay (Munsell Colors 2.5YR 3/1 “dark reddish gray” and 2.5Y 6/8 “olive yellow”) from a large rockshelter at the eastern edge of the site (our survey found no other source for this clay anywhere else on the escarpment or in the wetlands; superficial and excavated soils at Dos Ceibas are normally dark brown [Munsell colors 10YR 2/2 or 3/2 “very dark (grayish) brown”]; see Figure 3). They added rocks, Chicanel sherds, shell, and animal bone fragments. Then they poured this compact mixture on the existing soil to create a level plaza. In Group MP16, Structure R27-57 had a Preclassic predecessor. Its low platform rose slightly above the plaza on its west side (Figure 3d). It likely supported a building made of wood and thatched with palms. The compact Preclassic fill not only offers a stable foundation for perishable buildings but also visually set Group MP16 apart from its surroundings.

The Preclassic North Plaza had two buildings and an oversized plaza. Structure R27-63 started off as a simple platform and transformed into a two-stepped pyramid over at least six construction episodes (discussed further below). We identified Structure R27-62 as a Preclassic domestic building that was reused at the beginning of the Late Classic (Figure 3a). Below the Late Classic level was a gravel floor supported by 0.7 m of a dense dark-brown clay and rock fill (Figure 5). Construction technique and associated ceramic material date this floor to the Late Preclassic period. Below this first floor was a second gravel floor at an approximate depth of 1 m. Its fill, with a thickness of 0.5 m, consists of a dense brown clay-rock mix that was built on paleosoil. Domestic artifacts litter the surface of Structure R27-62's second floor. These include the neck of an unslipped jar, a partial Flor Cream dish, numerous remains of rodents, larger bone splinters, and carbon (Figure 6; inset in Figure 5). Unlike the fewer artifacts in the fill above, these artifacts and features are on or embedded in the gravel floor and were left behind when the building was rebuilt. They represent food trash and attest to the residential use of Structure R27-62. The rodents presumably died there searching for food.

Figure 5. South profile of the test pit into North Plaza's Structure R27-62 (vectorized profile drawing by Omar Schwendener with Eberl drawings of sherd profiles; colors approximate the Munsell Color that was measured in the field as closely as possible; in cases with similarly colored levels, however, we varied transparency to increase the contrasts between individual levels); the insets show an Early Nacimiento (Tepeu 1) plate sherd and the neck of an unslipped jar at the approximate depth of their discovery.

Figure 6. Artifacts from the second Preclassic floor surface of Structure R27-62 (Eberl photo and drawing): (a) Jar neck; (b) Partial Flor Cream dish with a paw-like projection on the flange.

The matrixes of Dos Ceibas's Preclassic constructions vary in color and constitution. Structure R27-62's two construction fills have brown hues and lack artifacts, unlike the Preclassic fills in Group MP16 and in the rest of the North Plaza. These differences set the two plazas and their buildings apart and point to differentiating practices. At the same time, they are less visible from the outside, where the hamlet in its entirety stood out from the black soil and green vegetation.

We suggest that Dos Ceibas's founders intentionally emplaced themselves. The brownish clays of their constructions set the settlement apart visually, making it look similar from the outside while marking internal differences. These local resources illustrate the deep native knowledge and interlace the human settlement with its surrounding landscape (Fisher Reference Fisher2023). A comparable construction technique with multicolored sands has been noted at Aguada Fénix much earlier and on a much more elaborate scale (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Vázquez López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Méndez Bauer, García Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020:531). The rockshelter as clay source may allude to the Maya origin story—most famously shown in San Bartolo's murals (Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube and Stuart2005:14–41)—in which humankind's ancestors step out of a cave and bring the gifts of civilization into the world (see also Eberl Reference Eberl2017:113–117). Hauling differently colored sediments to the site resonates with and possibly foretells Classic Maya notions of foundation (Martin Reference Martin2020:118–132). In relevant narratives, founders arrive from often mythically charged places of origin such as rockshelters and physically constitute them.

People's acts created Dos Ceibas. Discussions of placemaking often focus on the locale and its material qualities. Above, we shifted to the making—that is, how people emplace themselves. We argue that the Late Preclassic foundation of Dos Ceibas coincided with the development of a new subjectivity (Paynter Reference Paynter1989:383). Through their plazas and platforms, people created a public sphere and enabled new types of social interactions.

Negotiating differences

Kinship provides a powerful rhetoric to unite and differentiate people. In the Maya area, ancestor worship is ritually important and confers economic benefits (Douglass Reference Douglass2002:7–8; Isaac Reference Isaac1996; McAnany Reference McAnany1992, Reference McAnany, Sabloff and Henderon1993, Reference McAnany1995:96–97). Models propose the emergence of “early ritual areas” in which domestic compounds of founders turn into ceremonial places over time (e.g., Canuto Reference Canuto, Traxler and Sharer2016:482, 503–505; Powis and Cheetham Reference Powis and Cheetham2007; Rice Reference Rice, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017:138). For us, places are not a priori ritualistic but gather significance from repetitive practices (also Robin Reference Robin2013:158). In the following, we argue that Dos Ceibas's internal differences not only increased over time but also materialized in differential building activity. They may have originated with the veneration of the site's founders as ancestors. In the following, we discuss the transformation of Structure R27-63 and the North Plaza.

Dos Ceibas's eventual focal building—Structure R27-63—grew from a shrine to a small pyramid over the course of the Late Preclassic period (Figure 3). Our survey mapped two levels that reach a height of 3.5 m above the North Plaza. A monumental stairway with five steps (individual boulders are up to 0.6 m wide) leads to the first level. Looters uncovered at least two burials on top of the pyramid but did not continue deeper into the dense fill below the burials. Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan cleared the looters’ pit and continued with a test pit into the center of the pyramid (Figure 7). They stopped the excavation before reaching bedrock due to reduced space and the possibility of collapse (for excavation details, see Eberl Reference Eberl2014:199–202).

Figure 7. South profile of the test pit into North Plaza's Structure R27-63 (field drawing by D. Triadan, vectorized by Omar Schwendener; colors approximate the Munsell Color that was measured in the field as closely as possible); (inset) Preclassic incense-burner sherd from the looter's backfill (Eberl sherd drawing; due to its rarity, the sherd remains without type designation; compare to Adams Reference Adams1971:53; Rice Reference Rice1999:31–32; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975:60, Figure 70).

Structure R27-63 is a Preclassic building except for Floor 1 and the intrusive Late Classic burials (Table 2). Floors 2–7 consist of dense brownish clay mixed with limestone rocks similar to Preclassic constructions elsewhere in the region (Inomata Reference Inomata2008:145–146). Associated ceramics date these floors to the Late Preclassic period between 350 b.c. and a.d. 250. Structure R27-63 started as a simple platform. After Floor 5 had been leveled, a wall of irregular rocks was added in the eastern center. We interpret the wall as the base of a recessed second level and the earliest evidence for the two-level layout of the building's final version. A Preclassic incense burner sherd—the only example from the entire site—attests to the ceremonial nature of Structure R27-63 (inset in Figure 7). It likely came from Floor 2 or its fill, and it dates to the end of the Late Preclassic construction sequence. Multiple construction episodes, the form change, and the evidence for rituals attest to Structure R27-63's gradual transformation from platform to pyramid.

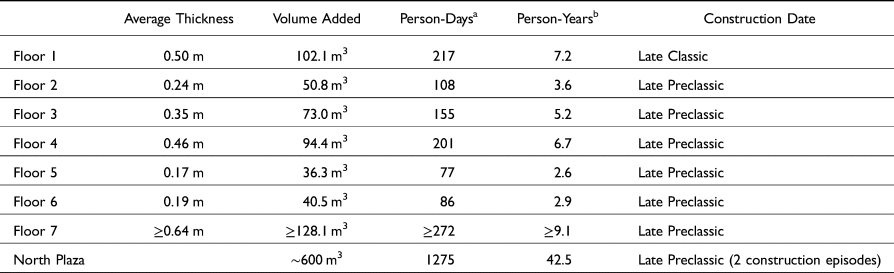

Table 2. Estimated labor expenditures for the construction of Dos Ceibas Structure R27-63 and the North Plaza (Eberl table).

a At least 2.125 person-days of labor were needed for every cubic meter of fill. This includes 1.67 person-days for quarrying, 0.25 person-days for transportation, and 0.21 person-days for fill construction (based on Abrams Reference Abrams1984:149–154, 160–162, 180). This estimate excludes specialized labor, such as the making of veneer stones and façade dressing, because of the unclear Preclassic appearance of Structure R27-63. Abrams's numbers reflect Late Classic construction techniques, and I assume that the latter are comparable to the much denser Preclassic fills.

b Person-years assume that every farmer can set aside one month or 30 spare days annually for nonagricultural work. The latter number is based on the agricultural cycle for traditional hoe agriculture in modern Tepoztlan (Lewis Reference Lewis1951:156).

The North Plaza in front of Structure R27-63 grew similarly over the course of the Late Preclassic period. The terrain slopes to the west and required a 1.5 m high leveling platform. Various excavations have enabled the reconstruction of its construction history (Figure 3; for excavation details, see Eberl Reference Eberl2014:196–198). The Late Preclassic predecessor of the North Plaza has roughly the same east–west extension as its Late Classic version, but it was smaller in the north–south direction. In particular, the plaza did not reach Structure R27-62, the Preclassic domestic building. The test pit in the southern center of the North Plaza exposed two Preclassic construction stages (Figure 3b). The builders first leveled the plaza with a gravel floor. They later added a 0.1 m high step that runs parallel to Structure R27-63 and probably led toward it as part of a stepped platform.

The North Plaza began as a residential group, with two buildings and a plaza in between. Above, we discussed that Structure R27-62 likely served residential purposes. Structure R27-63's location on the east side of the North Plaza suggests that it may have begun as a household shrine (see also Becker Reference Becker1971, Reference Becker1972, Reference Becker1991, Reference Becker and Sabloff2003, Reference Becker2004, Reference Becker2014). Over the course of the Late Preclassic period, the residential group acquired ceremonial and public functions.

Dos Ceibas's Preclassic inhabitants likely built the North Plaza. Each of Structure R27-63's Preclassic construction episodes added several dozen cubic meters of fill (Table 2). Labor estimates suggest that each floor required between 77 and circa 262 person-days of construction. North Plaza's Preclassic platform represents 1,275 person-days of labor. The total labor effort of 72.6 person-years shows that only a few workers were needed to build Structure R27-63 and the North Plaza. Enough people were likely living in Dos Ceibas during the Late Preclassic period to shoulder these constructions. Yet, the rapid expansion of North Plaza's platform suggests that the entire community—not only the inhabitants of the North Plaza—chipped in.

Our investigations at Dos Ceibas support the idea that early ritual areas emerge from domestic compounds of founders (e.g., Canuto Reference Canuto, Traxler and Sharer2016:482, 503–505; Powis and Cheetham Reference Powis and Cheetham2007; Rice Reference Rice, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017:138). Structure R27-62 and the North Plaza exemplify the transformation. Their multiple construction episodes echo community-based building projects elsewhere (Joyce Reference Joyce2004:18–19; Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Dobres and Robb2000). The North Plaza eventually outgrew domestic needs. Its last Preclassic version has an area of at least 1,200 m2, and about 333 people could assemble on it (based on a crowd estimate of 3.6 m2 per person, after Inomata Reference Inomata2006). This estimate exceeds the few families that lived in Dos Ceibas's Preclassic hamlet and likely even the total regional population (see discussion below). Public areas in the later village and at nearby sites are similarly oversized (Eberl Reference Eberl2014:227, Table 9.2). They likely accommodated multiple uses—from ceremonies, politics, and trade to sports—unlike more specialized plazas in urban centers.

During the Late Preclassic period, Dos Ceibas formed a community centered around a pyramid and a plaza (for a contemporary transformation of a comparable community, see Robin Reference Robin2013:109). The outward appearance of integration hides inequality. This tension is discernible in Dos Ceibas's construction history. Although the North Plaza saw extension and growth over the course of the Late Preclassic, Group MP16 remained stagnant. This process of diversification was more subtle than, for example, Paso de la Amada, where a private building was arguably enlarged into a chief's residence over time (Blake Reference Blake and Fowler1991). At Dos Ceibas, inhabitants expand not a residence but the potential shrine of the site's founders. They may have then employed ancestor worship in differential ways. In later times, the dead become partially anonymous ancestors or merge with supernatural beings (Eberl Reference Eberl2005:130–135); their veneration brings the wider community together, especially through jointly celebrated events. Yet, people do not forget their closeness to the founders and can use it to set themselves apart (see also Vadala and Walker Reference Vadala and Walker2020). Tikal Stela 31 exemplifies these two aspects of Maya ancestors. The dead father of Sihyaj Chan K'awiil II observes his son's coronation from the heavens. Bearing the features of the Sun God, he shines on all participants. At the same time, his headdress includes his name—Yax Nuun Ahiin I—as a reminder of Sihyaj Chan K'awiil's privileged relationship to him. Our interpretation differs from Robin's (Reference Robin2013:166–167) application of Blanton and colleagues’ (Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996) individual- versus group-oriented strategies with respect to ancestor veneration. From our perspective, Maya dead allow for both strategies by becoming partially generalized ancestors while retaining their identifying features.

Late Preclassic interactions in the Petexbatun region

Husserl's concept of empathy rests on social interaction. Einfühlung is directed at other people (see discussion above). At Preclassic Cerros, two types of interaction have been proposed to explain the emergence of community. According to the interaction sphere model, Cerros's inhabitants exchanged goods, people, and ideas with other communities in the lowlands (Freidel Reference Freidel1979). These regional interactions across social boundaries spread innovations. Alternatively, Vadela and Walker (Reference Vadala and Walker2020) propose interactions among the site's inhabitants across time. By passing their localized knowledge from one generation to the next, Cerros's inhabitants created new institutions such as ancestor worship and materialized them in their built environment. We reconceptualize these two types of social interactions as bordering and bonding. With bordering, we mean interactions that make people realize differences with others and identify who belongs to their community and who does not. The resulting border sets spatially separate groups apart. Community members also exclude fellow members. Intimate understandings of each other can lead to ostracizing, marginalizing, and even expelling misfits (Benedict and Benedict Reference Benedict and Benedict1982; Okely Reference Okely1975). Among Mesoamerican peoples, this aspect of bordering is most prominent as nagualism (Foster Reference Foster1944; Nash Reference Nash1967; Villa Rojas Reference Villa Rojas1963; Vogt Reference Vogt1969; see also Groark Reference Groark2008). With bonding, we refer to interactions through which people build sameness. Its basis is the recognition of similarities as part of empathy (see above). Bonding goes beyond that. By identifying shared characteristics and by negotiating which ones are relevant for a specific community, people essentialize sameness. Bordering and bonding are complementary and mutually reinforcing processes.

Several farming settlements coexisted during the Late Preclassic in the Petexbatun region (Figure 1). Dos Ceibas's inhabitants had neighbors at Aguateca, Punta de Chimino, and Bayak (Supplemental Text 2; Bachand Reference Bachand2006; Inomata Reference Inomata2008:129–136; O'Mansky Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Escobedo and O'Mansky1996; O'Mansky et al. Reference O'Mansky, Hinson, Wheat, Sunahara, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994; Van Tuerenhout et al. Reference Van Tuerenhout, Henderson, Maslyk, Wheat, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993). They could reach others within a few hours by walking or paddling a canoe. Despite their spatial proximity, they encountered settlements that looked remarkably different (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Preclassic settlements in the Petexbatun region (all shown to the same scale; labels identify buildings that have been investigated; blue areas mark excavations): (a) Aguateca's Group Guacamaya (the exact locations of test pits 8A-2 and -3 are uncertain; map based on Inomata Reference Inomata2008:130, Figure 3.116); (b) Punta de Chimino's Main Plaza (map based on Bachand Reference Bachand2006:82, Figure 6); (c) Bayak (exact test pit locations are uncertain; map based on O'Mansky et al. Reference O'Mansky, Hinson, Wheat, Sunahara, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994:429, Figura 42.15); (d) Dos Ceibas's North Plaza and Group MP16 (Eberl map).

Closest to Dos Ceibas was Aguateca's Late Preclassic settlement at the Guacamaya Group (Figure 8a; Inomata Reference Inomata2008:129–136). Platforms with potential residences on top surround a 6 m high pyramid (Structure K6-1). A few kilometers farther north is Punta de Chimino (Figure 8b; Bachand Reference Bachand2006). By the Late Preclassic period, a 1–2 m high acropolis supported a large main plaza, a possible E Group, and pyramidal Structure 6. The latter impressed less with its 3 m height and more with its 600 m2 extension. Bayak features 17 buildings dispersed loosely along the edge of the Petexbatun Lake (Figure 8c; O'Mansky Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Escobedo and O'Mansky1996). Structure 10 is the largest building with a height of 3–4 m. A wide terrace in front of its south side seems to have offered the only formal public space or plaza at Bayak.

Dos Ceibas, Aguateca, Bayak, and likely Punta de Chimino formed separate Late Preclassic communities (Supplemental Text 2). We argue that their architectural differences reflect attempts to set boundaries and to reinforce community identities. Dos Ceibas Structure R27-63 and its six Late Preclassic construction episodes exemplifies the localized and long-term investments of time and effort to create a community focus (see also Joyce Reference Joyce2004). The Petexbatun region's Preclassic settlements were smaller than centers elsewhere, but they did not grow in isolation. Monumental architecture such as pyramids and E Groups as well as public plazas are well-known characteristics of Preclassic centers across the Maya Lowlands. The size of Punta de Chimino's and Dos Ceibas's plazas likely exceeded the needs of the local population and allowed gatherings with outsiders. We argue that these social interactions involved community members of comparable wealth, status, and occupations and were not yet steered by an elite. In this regard, we differ from Bachand (Reference Bachand2006), who argues that Preclassic elites at Punta de Chimino ruled over satellite communities elsewhere. Our comparisons show, though, that all four Preclassic sites differ in their layout and other details; in addition, Bayak was likely the largest Preclassic settlement in the Petexbatun region (Figure 8; Supplemental Text 2).

Community as new subjectivity

In The Domestication of Europe, Hodder (Reference Hodder1990) argues that Old World farmers domesticated plants and animals and, in the process, created a new world and worldview, exemplified by the domus. We argue for the emergence of a similarly new subjectivity among the Preclassic inhabitants of Dos Ceibas (see also Paynter Reference Paynter1989:383). Based on Husserl's concept of empathy, we critique equating similarity with sameness. People recognize others as foreign egos based on their bodies and behaviors, but they do not mistake them for themselves or overlook socioeconomic differences. Empathy allows people to become community members. At the same time, they negotiate continuing differences among community members. The creation of community is an ongoing political process. Instead of assuming an essential list of shared characteristics, we emphasize how they become essentialized. We apply this model to the Late Preclassic hamlet of Dos Ceibas in the Petexbatun region. We argue that Dos Ceibas's Preclassic inhabitants developed a new sense of being as community members. We ask how they materialized community, how they created unity in a political process, and how they employed bordering and bonding interactions. Our conceptual framework allows for context-specific forms of community. Farmers may interact with and perceive each other differently than foragers do; their forms of emplacement and their subjectivities will likely vary as well.

Our investigations at Dos Ceibas allow reconstructing a Preclassic hamlet consisting of at least three Late Preclassic buildings and two plazas. Two platforms (Structures R27-57 and R27-62) likely had residential uses. Structure R27-63 and the North Plaza formed—at least in their eventual configuration—a ceremonial and public sphere. The unusually large North Plaza provided space for communal events as well as interactions with visitors from elsewhere (see also Robin Reference Robin2013:109).

Dos Ceibas's settlement history shows that the North Plaza originates as a residential group. Over at least six construction episodes, locals transformed Structure R27-63 from a platform (and possible household shrine) to a small pyramid. They also expanded the North Plaza. These developments fit the emergence of early ritual areas elsewhere in the Maya Lowlands. The privileged inclusion of one domestic building (Structure R27-62) in this emerging ritual complex alludes to incipient stratification. The builders’ focus on the North Plaza rather than on Group MP16 materializes inherent differences that may reflect differential ancestor worship. Celebrating ancestors in the sense of generalized predecessors allows people to bring their community together. At the same time, they do not forget their line of descent and can leverage their proximity to founders to set themselves apart.

Through centuries of work, Dos Ceibas's inhabitants established a localized identity. They lived in walking distance from three Late Preclassic settlements. Their neighbors emplaced themselves differently and each created a locally unique architectural appearance. The architectural diversity suggests distinct community identities. After the Late Preclassic period, or a.d. 250, Dos Ceibas was likely abandoned for centuries, and its Preclassic community withered only to be resurrected in a different form around a.d. 600. These synchronic and diachronic processes emphasize the continual creation and re-creation of communities.

Acknowledgments

We thank three anonymous reviewers for their critical remarks and suggestions on how to improve earlier drafts. Licentiate Ervin Salvador López, Maestro Erick Ponciano, and Licentiate Juan Carlos Pérez at Guatemala's Instituto de Antropología e Historia graciously provided work permits (esp. Convenio 17-2008) and gave permission for the publication of this article. Omar Schwendener and Pablo Rodas supervised excavations in Dos Ceibas's center. Omar Schwendener vectorized most of the field drawings.

Funding statement

The National Science Foundation supported Eberl's initial investigations under Dissertation Improvement Grant No. 0514563 (with E. Wyllys Andrews, V as PI). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Funding for later investigations came from the Middle American Research Institute and the Roger Thayer Stone Center for Latin American Studies at Tulane University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

No original data were used.

Supplemental materials

Supplemental Text 1. Reconstructing the spatial extension of Dos Ceibas's Preclassic hamlet.

Supplemental Text 2. Preclassic settlements at Aguateca, Bayak, and Punta de Chimino.

Supplemental Figure 1. Spatial distribution of Preclassic rim-sherd frequencies at Dos Ceibas (measured as the percentage among all datable sherds; each data point summarizes the investigations in a group; the nearby site of Cerro de Cheyo is shown for comparative purposes).

Supplemental Figure 2. Ceramic sherd densities on the surface and in the topsoil at Dos Ceibas; labels identify groups with Preclassic sherds.

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536124000117