Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 May 2022

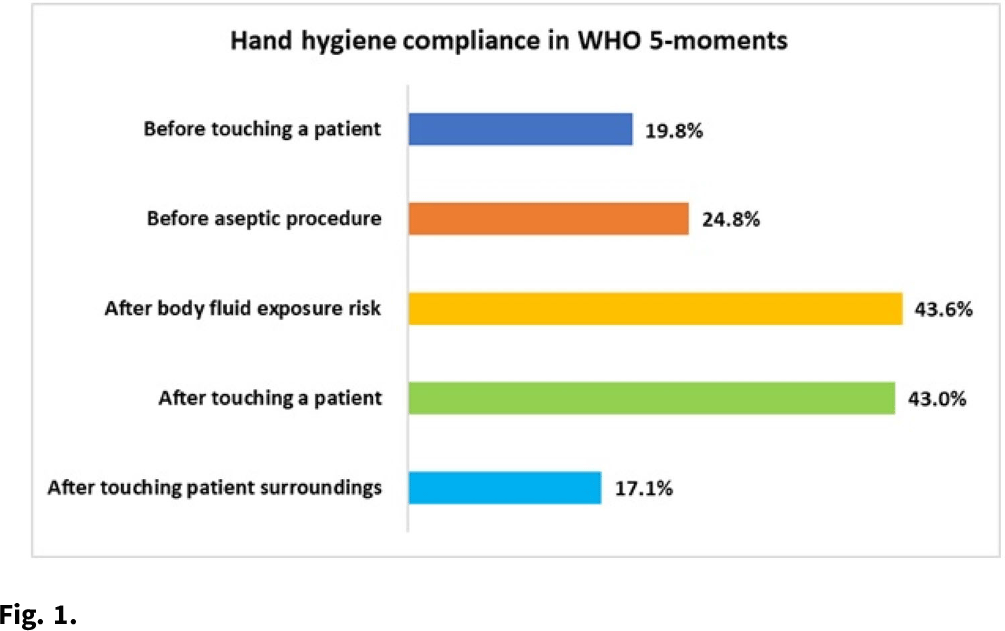

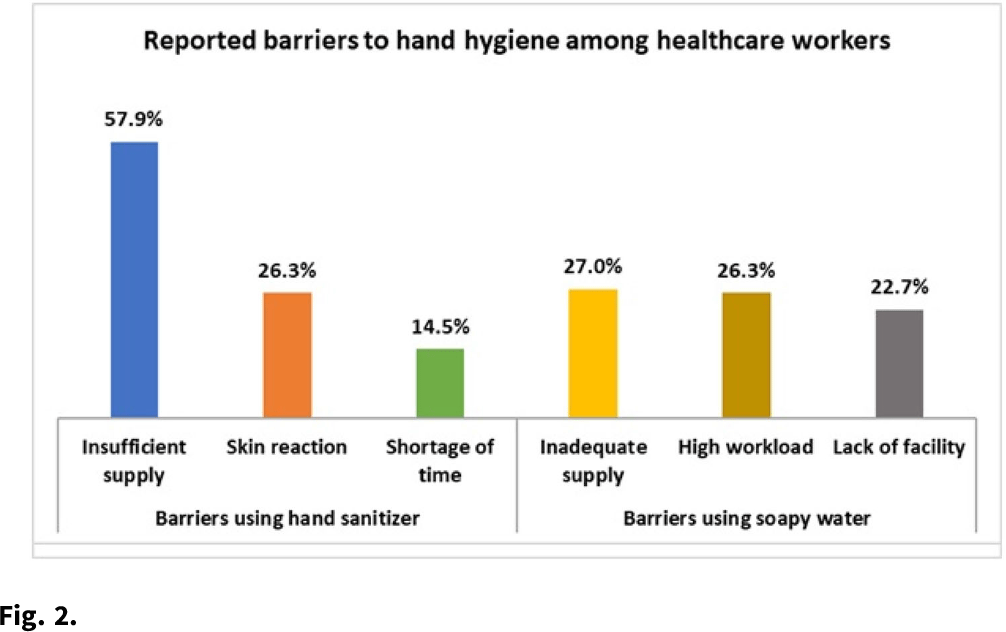

Background: Hand hygiene (HH) is a core element of patient safety and the single most essential strategy for preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Adherence to HH among healthcare workers (HCWs) varies greatly depending on a range of factors, including risk perceptions, institutional culture, auditing mechanisms, and availability of HH supplies. We observed HH compliance among HCWs to determine the factors influencing practices in tertiary healthcare facilities in Bangladesh. Methods: During September 2020–February 2021, we conducted nonparticipatory observations at 11 tertiary-care hospitals in Bangladesh using the WHO “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene” tool to record compliance among physicians, nurses, and cleaning staff. We also performed semistructured interviews to determine the key barriers to complying with hand hygiene. Furthermore, we noted the presence, location, and functionality of existing HH stations within each hospital ward. Results: We observed 14,668 HH opportunities among HCWs. The overall HH compliance was 25.3%, and compliance differed significantly by professional category (P < .001). Physicians had the highest HH compliance at 28.5% (2,264 of 7,930), followed by nurses at 25.4% (1,272 of 5,008). Cleaning staff had the lowest rates of HH at 9.9% (171 of 3,221). HCWs of public hospitals had significantly higher odds of complying with HH practices than those in private hospitals (27.4% vs 17.9%; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.55–1.93; P < .001). HH compliance also varied by WHO Five Moments indicators. HCWs were 3 times more likely to perform HH ‘after touching a patient’ than ‘before touching patient’ (aOR, 3.36; 95% CI, 2.90–3.90; P < .001). Common barriers to using hand sanitizer were insufficient supply (57.9%), skin reaction (26.3%), shortage of time (14.5%), and lack of awareness (11.9%). Regarding handwashing with soap, inadequate supplies (27.0%), high workload (26.3%), and lack of facilities (22.7%) were the key factors for low adherence. The HH infrastructure observation in 82 wards showed that running water and soap were available in 168 (86.2%) of 195 HCW-designated basins, compared to 51 (35.9%) of 142 for the patient- and attendant-assigned basins. Handwashing posters were found in only 44 (13.1%) of 337 basin surroundings, and no hand drying supplies were observed for patients or attendants. Conclusions: Hand hygiene compliance among HCWs fall significantly short of the standard for safe patient care. Inadequate HH supplies in a resource-constrained setting like Bangladesh demonstrates a lack of leadership in prioritizing, promoting, and investing in infection prevention and control. The findings of this study might help to motivate and design interventions for HH compliance, which will help reduce HAIs in the hospital setting.

Funding: None

Disclosures: None