Research background

I saw in my journey to York many hundreds of tumuli, which I take to be Roman […] at Arras on this side Wighton, not mentioned in any author which I intend to dig into and take a whole account and descriptions there of (Abraham de la Pryme, January 1699, quoted in Jackson Reference Jackson1870: 200).

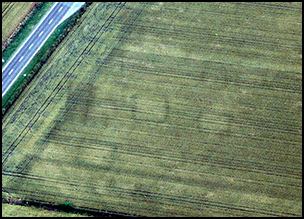

Arras, once a medieval village but now reduced to a farm and a few cottages, is situated on a high point of the Yorkshire Wolds, 5km to the east of Market Weighton (de la Pryme's Wighton). It was not until 1815–1817 that some of the tumuli (burial mounds) noted by de la Pryme were excavated by Edward Stillingfleet, Barnard Clarkson and Thomas Hull, and mapped by William Watson in August 1816 (Figure 1) (Stead Reference Stead1979). Their spectacular discoveries included two burials containing the remains of chariots. One became known as the ‘King's barrow’ because of the relative richness of the harness fittings and the two horses buried in the grave. The other vehicle burial was named the ‘Charioteer's barrow’ due to the comparative plainness of the artefacts. A burial of a female with a gold ring and many glass beads was called the ‘Queen's barrow’. In 1850, the Yorkshire Antiquarian Club undertook further excavations, followed by those of Canon William Greenwell in 1876, who recorded a third chariot burial. Ian Stead conducted limited excavation there in 1959, following a magnetometer survey by Martin Aitken, one of the earliest undertaken in the UK (Stead Reference Stead1979).

Figure 1. William Watson's map of the Arras cemetery, dated 5 August 1816 (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

The importance of the Arras cemetery and its early archaeological investigation made it the eponymous site for the so-called Arras Culture, giving it an iconic status within British Iron Age studies. The Arras Culture is perhaps best known for its chariot burials: all but three of the 29 or so UK examples are in eastern Yorkshire. The rather exotic character of Arras Culture chariot graves in Iron Age Britain, their resemblance to burials in northern France, and the name of the group inhabiting the region during the Roman era, the Parisi, led to suggestions of migration, which is still a topic of considerable debate.

Arras 200: the new surveys

To commemorate the bicentenary of the original discoveries, and to monitor the present condition of the Arras cemetery site, a team directed by Peter Halkon undertook a new geophysical survey there in autumn 2017, covering 23ha using a Foerster cart-mounted magnetometer with GPS (Figure 2). A limited resistivity survey was also conducted by the East Riding Archaeological Society.

Figure 2. The landscape setting of the 2017 magnetometer survey at Arras, conducted by James Lyall (photograph by P. Halkon).

The Arras cemetery comprises square barrows, which are square enclosures surrounding a central burial, covered by a mound created from the ditch spoil. Some have a central grave pit; in others, the burial was placed directly on the ground's surface. Certain cemeteries in the region also contain small round barrows. The earliest square barrows date from the later fifth century BC, continuing into the first century BC. Eastern Yorkshire contains the biggest concentration of square barrows in the UK, a burial type that closely resembles those in northern France and Belgium, with outliers as far east as the Czech Republic (Stead Reference Stead1979; Halkon Reference Halkon2013).

During the 2017 magnetometer survey, 34 barrows were detected (Figure 3), a surprisingly low figure considering many more are recorded through aerial photography and on earlier maps. Watson plotted 88 barrows in 1816 (Figure 1). A further 12 were added by the Yorkshire Antiquarian Club excavation of 1850 (Stead Reference Stead1979). On the 1852 Ordnance Survey map, only 29 remained upstanding. In 1890, 13 barrows were mapped by the Ordnance Survey, 11 in 1953 and only three in 1959. By 1970, none survived above the ground's surface (Stead Reference Stead1979). Stead (Reference Stead1979) collated all existing information, recording that originally there were at least 100 barrows. Aerial photography in the 1970s and 1980s revealed still more barrows appearing as crop marks; these were plotted by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) (Stoertz Reference Stoertz1997). This survey showed the scale of the cemetery and its relationship with other features, including a settlement consisting of a drove-way flanked by enclosures extending over 1km to the north.

Figure 3. Magnetometer survey results. The frequent parallel lines across the plot are glacial features (figure by J. Lyall).

Results and discussion

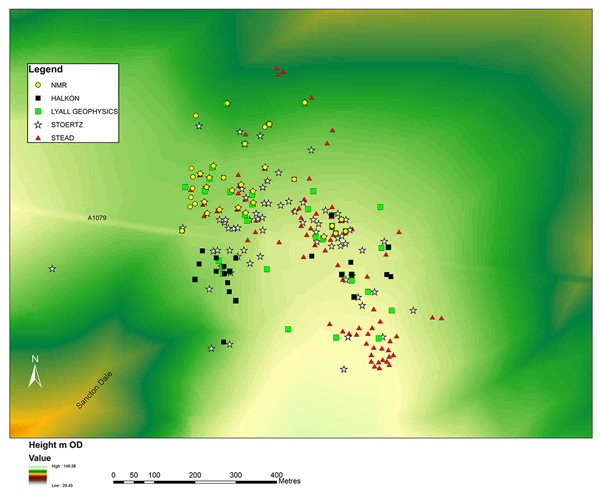

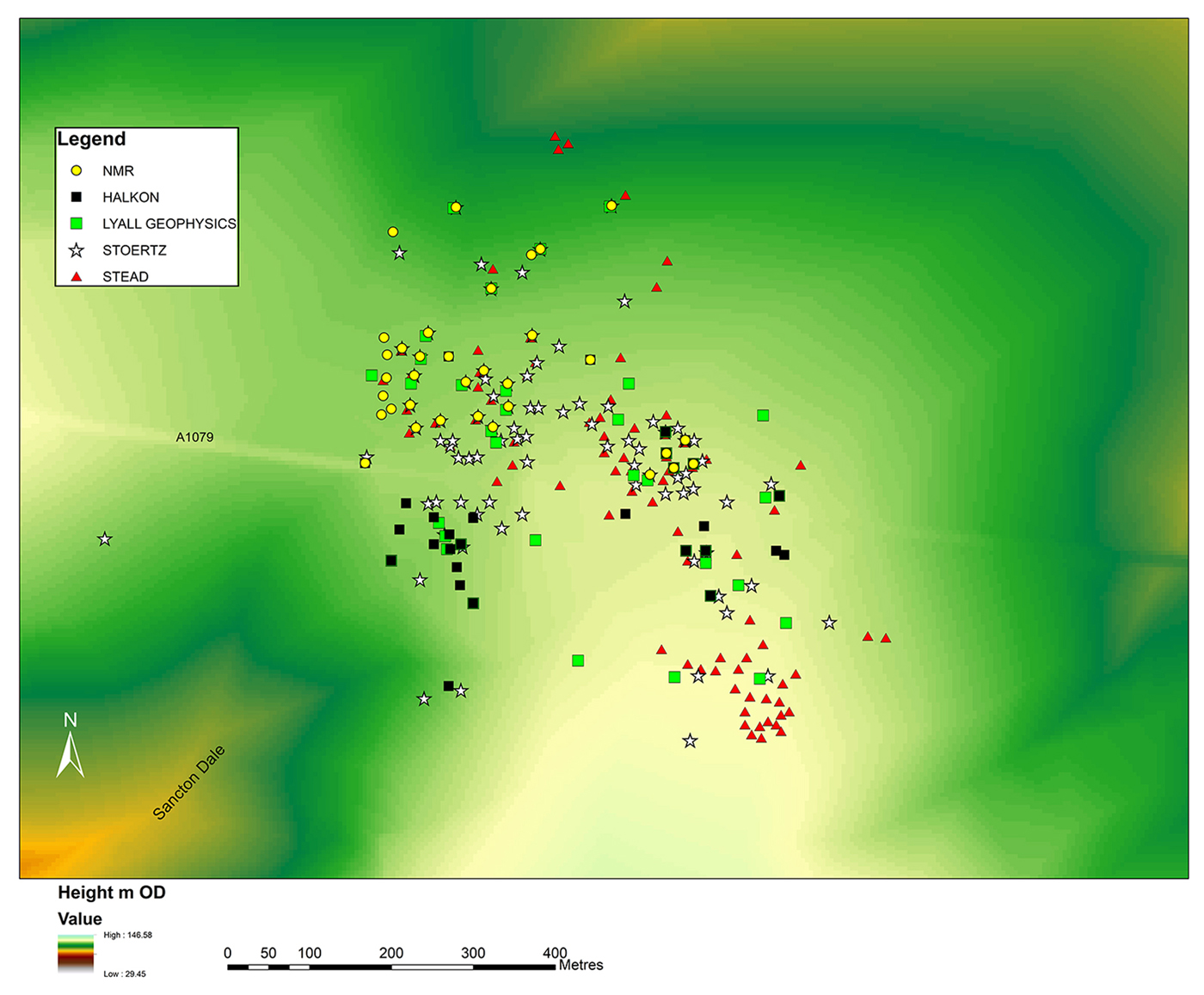

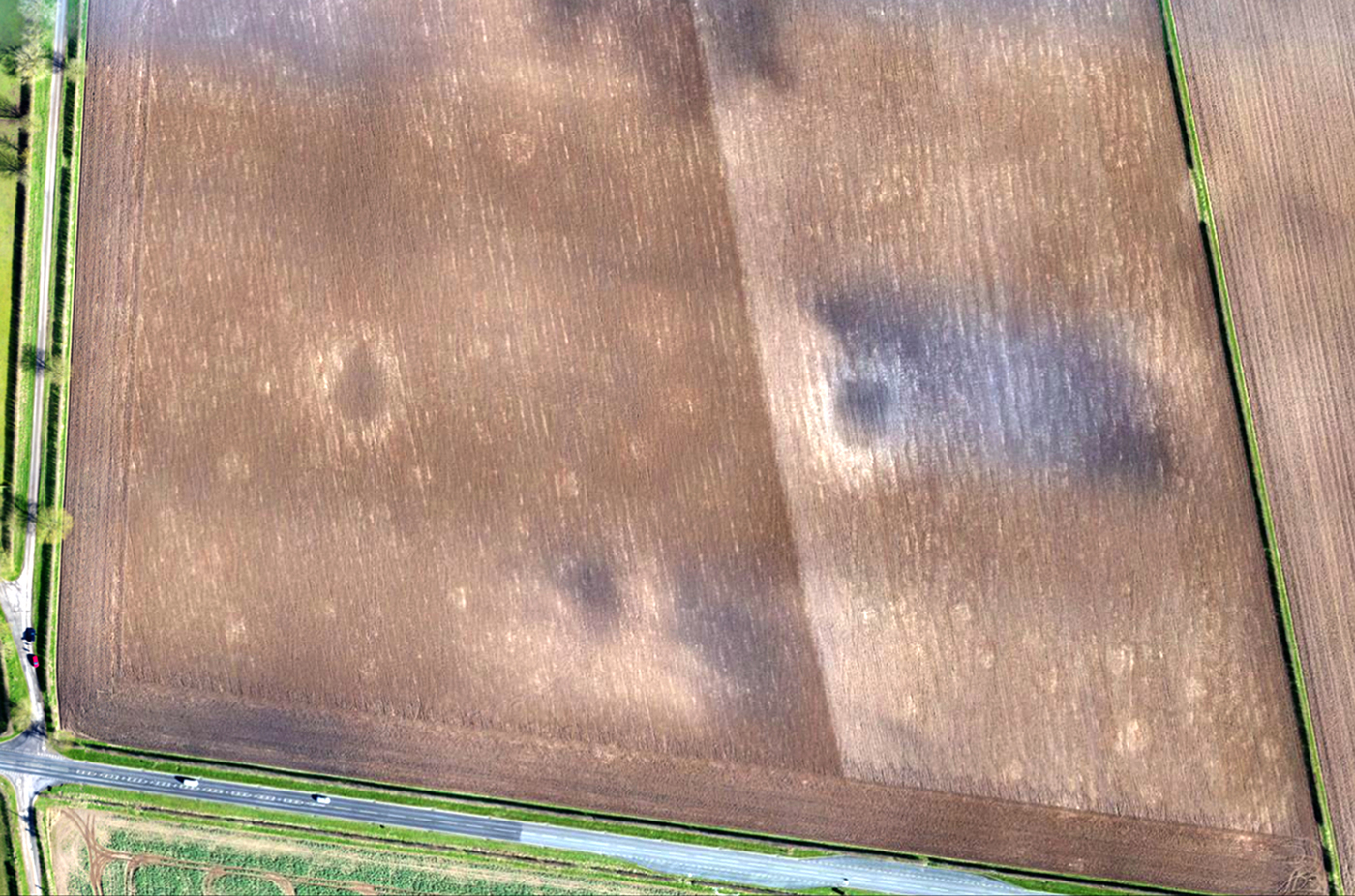

Due to the considerable disparity between the geophysics results and the barrows previously plotted, all available sources of information were consulted including Google Earth imagery from 2007, aerial photographs held by Historic England's National Monuments Record and aerial photographs taken in the 1990s, 2007 and 2010 (Figure 4). The results have been integrated into a database that provides a concordance between all the different sources of information, giving a total of about 200 barrows within the Iron Age cemetery (Figure 5). Most of them were of the larger type, with rounded corners and no visible central grave. It should be noted that glacial features on the geophysics plot and aerial photographs make barrows in some areas difficult to distinguish. The difference between the number of barrows detected through aerial photography and geophysics may also be explained by unresponsive ditch fills, or plough damage. This was confirmed through drone photography on the north side of the A1079 in April 2018, which showed that only 40 barrows were still visible as soil marks, many of these scarred by cultivation in recent years (Figure 6). Only the nine Bronze Age round barrows are scheduled ancient monuments, and none of these now stand above the field surface.

Figure 4. Aerial photograph of the cemetery, August 2005 (photograph by P. Halkon).

Figure 5. Square barrow distribution drawn from all sources (figure by P. Halkon).

Figure 6. The cemetery in April 2018, after ploughing (UAV photograph by Tony Hunt, Yorkshire Archaeological Aerial Mapping).

This new project exemplifies the benefits of an integrated approach, combining historical research, aerial photography, geophysical survey and excavation results. For the first time we have a complete picture of the iconic Arras cemetery and its limits. While still lacking a detailed chronological sequence, we can now start to identify different clusters of barrows that might reflect family groups within the cemetery (cf. Figure 5). Moreover, the presence of the Bronze Age barrows could indicate an attempt by Iron Age peoples to establish a link with previous monuments in the landscape, as an act of territorial appropriation or alternatively as the imposition of a new burial rite. The Arras cemetery was placed in a prominent landscape position with long views south towards the Humber Estuary and northwards over a major valley through the Yorkshire Wolds. Access to the Iron Age settlement from Sancton Dale to the south would have been through the cemetery. It might be no accident that centuries later the foot of Sancton Dale became the location of a large Anglo-Saxon cremation cemetery, suggesting a similar territorial claim by new incoming peoples.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Leverhulme Trust, East Riding Archaeological Society and the Yorkshire Archaeological and Historical Society for their financial support, and the local farmers for allowing access to the fields. Many thanks to Julia Farley of the British Museum for arranging use of the William Watson map.