Introduction

The wetland site of Järvensuo 1 was a chance discovery during the digging of a ditch in the 1950s. The first find in the drainage ditch was a wooden paddle, which yielded a radiocarbon date of 4210±140 BP (Hel-1004: 3331–2462 BC at 95.4%; date modelled in OxCal v.4.4, using IntCal20 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020)), placing it in the Neolithic. More prehistoric artefacts, including a wooden scoop with a handle carved to resemble a bear's head, fishing implements and pottery were uncovered in the same ditch in the 1980s. Archaeological inspection, palaeobotanical studies and small-scale excavations followed (e.g. Aalto et al. Reference Aalto, Siiriäinen and Vuorela1985; Siiriäinen Reference Siiriäinen1987), but, unfortunately, most of this work remains unfinished.

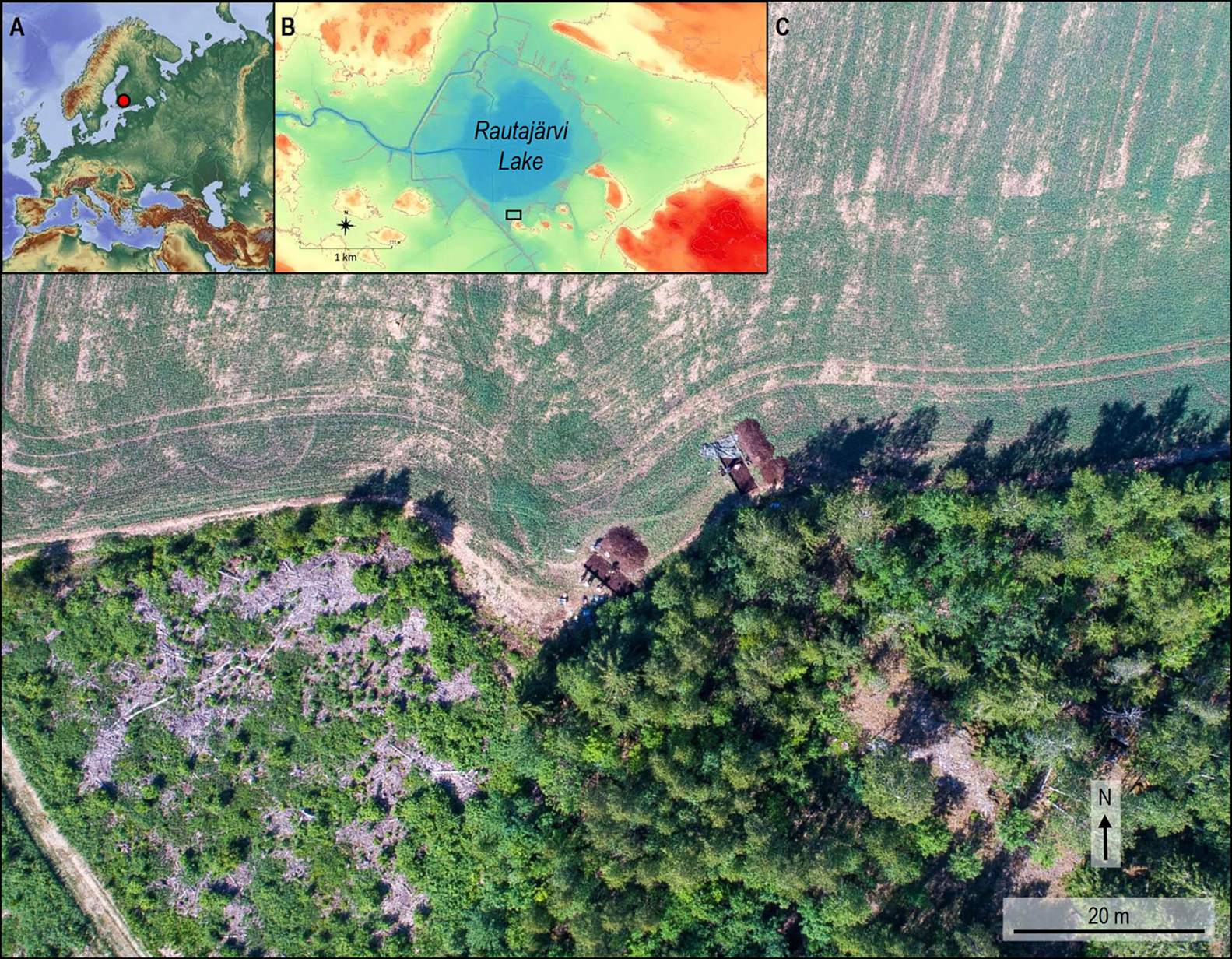

The site is located in south-west Finland at the foot of a moraine hill rising in the middle of a large peatland plateau (Figure 1A–B). The archaeological horizon resulting from human occupation and resource procurement (c. 4000–2000 BC) lies today within peat and underlying gyttja (eutrophic mud) by the southern shore of the drained Rautajärvi Lake. The lake was isolated from the Baltic Sea during the Ancylus Lake phase, c. 9800 BP, and it was transgressive until 4500 BP, when a new outflow channel lowered the water level abruptly and revealed a flat shoal zone. The water-level fluctuation and sedimentation have resulted in formation processes that have aided the preservation of organic archaeological remains.

Figure 1. a) Location map; b) study area at Järvensuo; c) aerial photograph of the site (elevation data by National Land Survey of Finland; photograph by V. Laulumaa; figure by S. Koivisto).

New research commenced at Järvensuo after 35 years, and the first season of two excavations over the course of 2020 and 2021 concentrated on the lakeshore with the aim of shedding new light on prehistoric activities and the preservation of organic materials in a heavily drained habitat (Figures 1C & 2). The fieldwork revealed more than 5000 years of stratigraphy and yielded rich evidence of sedimentation, environmental conditions and anthropogenic activities.

Figure 2. Fieldwork in progress in 2020 (photograph by S. Koivisto).

Snake figurine

A delicately carved wooden snake figurine was discovered in a horizontal position in peat overlying gyttja at a depth of approximately 0.6m (Figure 3A). Here the peat consists of a distinct bed of moderately decomposed sedge (Carex) and reed (Phragmites), indicating lush water meadow vegetation at the time of deposition. The figurine was lying on its right side, either having been lost, discarded or intentionally deposited amidst the thick lakeshore vegetation.

Figure 3. a) The snake figurine in situ; b) the excavated artefact photographed from above (photographs by S. Koivisto).

The figurine is 535mm long and 25–30mm thick, and it has been carved from a single piece of wood (species analysis ongoing), its surface being completely worked with no ornamentation. The neck is narrowed and the slender body is formed by two carved bends continuing to the tapering tail (Figure 3B). The flat angular head is portrayed in a slightly raised position with an open mouth (Figure 4). The figurine is very naturalistic and resembles a grass snake (Natrix natrix) or a European adder (Vipera berus) in the act of slithering or swimming away. The direct radiocarbon date of the artefact yielded a Late Neolithic date of 3908±32 BP (Ua-67655: 2471–2291 BC at 95.4% (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020)).

Figure 4. Detail of the head profile (photograph by S. Koivisto).

The snake motif in the North European Neolithic art

The figurine is hitherto unique in style and character. A somewhat far-fetched point of comparison may be found in a small Neolithic clay figurine from Hietaniemi approximately 100km north-west of Järvensuo, which portrays a petite snake curled up with a raised head (Edgren Reference Edgren1967). In the Eastern Baltic, the Urals and European Russia snakes are occasionally portrayed in Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age portable art made of amber, antler, bone, lithics, wood and clay (e.g. Chairkina Reference Chairkina2014; Kashina Reference Kashina, Kostylyovoi and Averina2015). Other animals (waterfowl and elks) and occasionally humans are more typical as motifs. Snake-like figurines made of wood have been found at Gorbunovo, Zamostje 2, Sārnate and Šventoji (Rauschenbach Reference Rauschenbach1956; Vankina Reference Vankina1970; Rimantienė Reference Rimantienė2005; Lozovskaya Reference Lozovskaya2020).

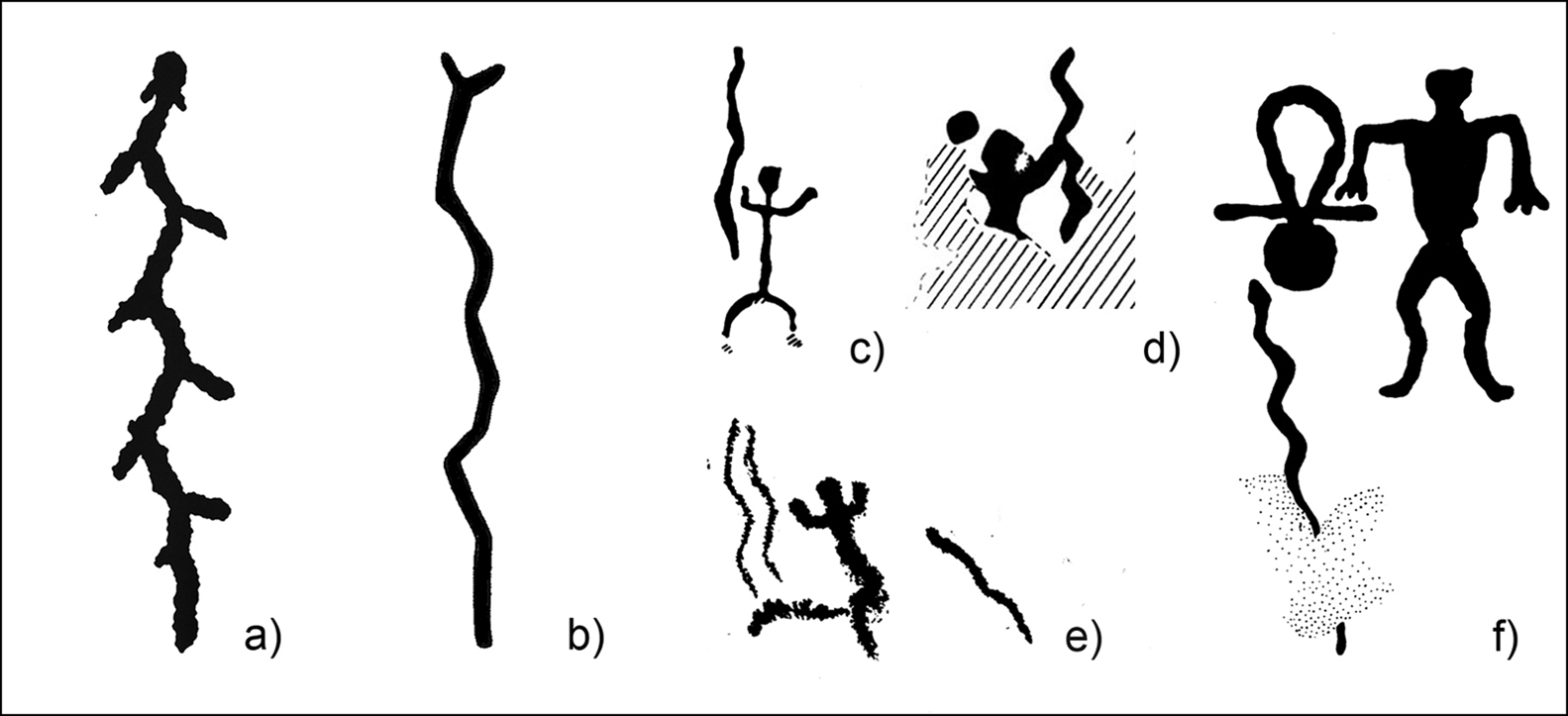

Snakes are occasionally also depicted in North European rock art (Figure 5). A dozen or so snake-like figures are known among the Neolithic rock carvings of Lake Onega and the White Sea, Karelia (Savvateyev Reference Savvateyev1970; Poikalainen & Ernits Reference Poikalainen and Ernits2019). The broadly contemporary rock carvings in the Kola Peninsula likewise feature a few possible snakes, one of which seems to have an open mouth like the Järvensuo figurine (Figure 5b) (Kolpakov & Shumkin Reference Kolpakov and Shumkin2012: 191). Furthermore, the red ochre rock paintings of both Sweden and Finland (dated c. 5200–1500 BC) feature a few images of snakes (Lahelma Reference Lahelma2008). Interestingly, at some sites a human figure appears to be holding a snake in his or her hand, and thus may in fact depict a carved snake figurine or staff (Figure 5c–d).

Figure 5. Depictions of snakes in North European Neolithic rock art from the following localities: a) Lake Onega; b) Kola Peninsula; c–e) Finland; f) White Sea (figure by A. Lahelma).

The significance of the Järvensuo figurine

Great caution must be exercised in interpreting a practically unique find such as the Järvensuo figurine, particularly as the character of the site is not yet fully understood. The high number of fishing-related artefacts at Järvensuo suggest economic activities, yet with a possible ritual element related to the use of the lakeshore. It is unclear whether the figurine was a freestanding sculpture or a staff (or both), and either way a multitude of interpretations is possible (cf. Iršėnas Reference Iršėnas2007). As a preliminary hypothesis, it seems reasonable, however, to place the artefact in the religious sphere. Snakes are loaded with symbolic meaning in both Finno-Ugric and Sámi cosmology, and shamans were believed to be able to transform into snakes (Autio Reference Autio, Ahlbäck and Bergman1991; Siikala Reference Siikala2002). Moreover, the Land of the Dead was believed to lie under water, which seems interesting given the wetland setting of the Järvensuo figurine.

Acknowledgements

Harri Vasander is thanked for peat examination, and the Finnish Heritage Agency for fieldwork collaboration.

Funding statement

Research at Järvensuo is funded by the Academy of Finland (decision 322331).