Introduction

During the European Final Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic, material culture seemingly diversified. This emergence of regional groupings, supposedly characterised by new stone tools or novel technologies, is often thought to signify adaptations to changing climates and environments. Opinions differ, however, on the degree to which environmental changes in the form of the contemporaneous climatic cycles or extreme events, such as the Laacher See volcanic eruption, forced these changes, or whether they relate primarily to dynamics of cultural transmission (see Kabacinski & Sobkowiak-Tabaka Reference Kabacinski and Sobkowiak-Tabaka2011; Riede Reference Riede2017). Furthermore, recent work reconnects with earlier critiques of Final Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic cultural taxonomy (e.g. Kobusiewicz Reference Kobusiewicz, Street, Barton and Terberger2009) in pointing out that many of the period's cultures, industries and facies may be artefacts of research history, rather than reflecting contemporaneous cultural variability (Sauer & Riede Reference Sauer and Riede2019; Ivanovaite et al. Reference Ivanovaite, Serwatka, Hoggard, Sauer and Riede2020). Indeed, the entire cultural taxonomic framework for the Upper and Final Palaeolithic seems to be in epistemological crisis (Reynolds & Riede Reference Reynolds and Riede2019).

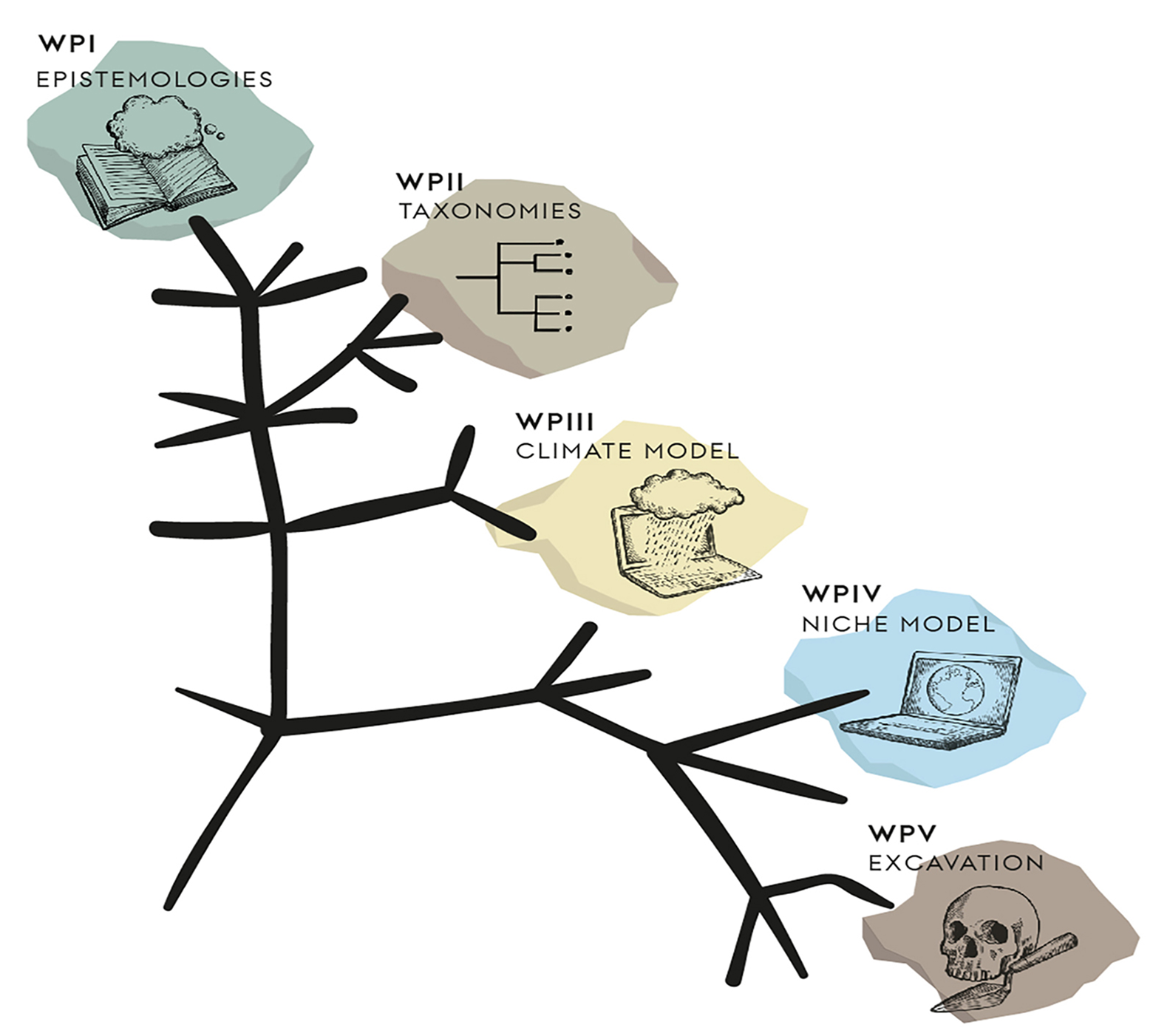

CLIOARCH (CLIOdynamic ARCHaeology: computational approaches to Final Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic archaeology and climate change) seeks to revitalise cultural taxonomic research in the period from 15 000–11 000 years BP—encompassing the Late Glacial and Early Holocene—and to combine state-of-the-art climate modelling (Mauritsen et al. Reference Mauritsen2019) with fully reproducible eco-informatics methods to answer long-standing questions of cultural relations and adaptations. Finally, the project will ground-truth its in silico results through excavations, specifically targeting stratified rockshelter locales (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The five CLIOARCH work-packages in its signature visual language, arranged on an evolutionary tree inspired by one of Charles Darwin's own notebook sketches from 1837 in reference to the project's cultural evolutionary approach (cf. Archibald Reference Archibald2014; figure by the authors).

Critical research history is essential in untangling the epistemological inconsistencies that plague the Final Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic. The turbulent times of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries during which archaeology developed as a discipline have left an indelible mark on present practice (Díaz-Andreu Reference Díaz-Andreu2007), including research on the Palaeolithic (e.g. Tomášková Reference Tomášková2003; Clark Reference Clark, Camps and Chauhan2009). CLIOARCH's point of departure is the observation that many of the Final Palaeolithic stone tool type fossils—mostly defined some time ago—no longer hold the culture-historical diagnostic power once ascribed to them (Serwatka & Riede Reference Serwatka and Riede2016), and that the many maps intended to portray contemporaneous cultural diversity are in evident contradiction to each other (Riede et al. Reference Riede, Hoggard and Shennan2019). Critically, the methods and data used to define the original cultural units or their spatial representation are rarely, if ever, transparent or reproducible. In light of recent calls for Open Science in archaeology (Marwick Reference Marwick2017) and parallel developments in quantitative history—‘cliodynamics’ (Turchin Reference Turchin2008)—CLIOARCH deploys a model- and data-driven approach to move our understanding of this period forward substantially.

CLIOARCH will use cultural evolutionary theories and methods—especially geometric morphometrics and cultural phylogenetics—to capture long-term techno-typological transformations. Cultural phylogenies have the potential to form the basis not only for refining existing taxonomies but also for rethinking adaptation (cf. Collard & Shennan Reference Collard, Shennan, Stark, Bowser and Horne2008). The project will assemble an up-to-date geo-referenced database of relevant find localities and their characteristics so that subsequent analyses and accompanying climate model simulations will be able to address change over both time and space. This will enable them to capture changing ways of relating to unstable environments and changing technological traditions. Once novel cultural taxa are identified, distribution modelling approaches (e.g. Svenning et al. Reference Svenning, Fløjgaard, Marske, Nógues-Bravo and Normand2011) can be applied to define the adaptive envelopes or niches specific to them in a statistical way that also accounts for the historical relatedness amongst these taxa. As pioneered elsewhere (e.g. Benito et al. Reference Benito, Svenning, Kellberg-Nielsen, Riede, Gil-Romera, Mailund, Kjaergaard and Sandel2017; Whitford Reference Whitford2019), distribution modelling enables us to extract the specific topographic and environmental parameters linked to different taxonomic groupings and so to infer their ecocultural adaptations. Ultimately, the predictive power of these distribution models in combination with regional registers will allow us to search for new stratified locales from the Final Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic in a targeted manner.

Acknowledgements

The CLIOARCH project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 817564).