Introduction

Since 2004, the Monte Bernorio Institute for the Study of the Ancient Cantabric (IMBEAC) has carried out excavations and surveys at the Iron Age oppidum (a large fortified settlement) of Monte Bernorio (Palencia, Spain) and its wider surroundings. Fieldwork has recently expanded in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh. The results provide ground-breaking evidence to improve our knowledge of the Iron Age and Roman periods in northern Spain.

The Iron Age oppidum

The oppidum of Monte Bernorio is one of the largest Iron Age settlements on the Iberian Peninsula (Torres-Martínez et al. Reference Torres-Martínez, Fernández-Götz, Martínez-Velasco, Vacas and Rodríguez-Millán2016). The site occupies the upper part and side of Monte Bernorio (Figure 1). Located in a strategic position at the centre of the foothills of the Cantabrian Mountains, it dominated an important intersection of communication routes. Occupation of the site started in the ninth to eighth centuries BC and continued until the late first century BC. The Iron Age settlement is surrounded by a number of cemeteries located at the foot of the mountain. Excavations in the late nineteenth century revealed wealthy graves containing daggers of the so-called ‘Monte Bernorio type’, whereas recent fieldwork has provided evidence for some modest burials and a ditch enclosing a funerary space.

Figure 1. Monte Bernorio, with the Cantabrian Mountains in the background (photograph by D. Vacas, modified by J.F. Torres-Martínez & A. Martínez-Velasco).

Recent excavations have shown that towards the end of the Iron Age, the upper part of Monte Bernorio was fortified by a stone wall and ditch, which enclosed an area of 28ha. In addition, the area surrounding Monte Bernorio's perimeter had a system of large concentric earthen ramparts, which expanded the area of the oppidum to at least 90ha. These defences are multivallate—built as a series of discontinuous ramparts—and constitute one of the most impressive defensive works in the whole of Iron Age Europe. An extremely large quantity of finds and several Late Iron Age house structures have been documented within the oppidum. The finds include copious amounts of pottery and animal bones, metal ornaments, tools, weapons, glass beads, imported objects and some coins. An exceptional find was a tessera hospitalis (hospitality agreement) featuring a Celtic-language inscription (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tessera hospitalis from Monte Bernorio with an inscription in a Celtic language (© IMBEAC).

The ritual landscape of Mata del Fraile

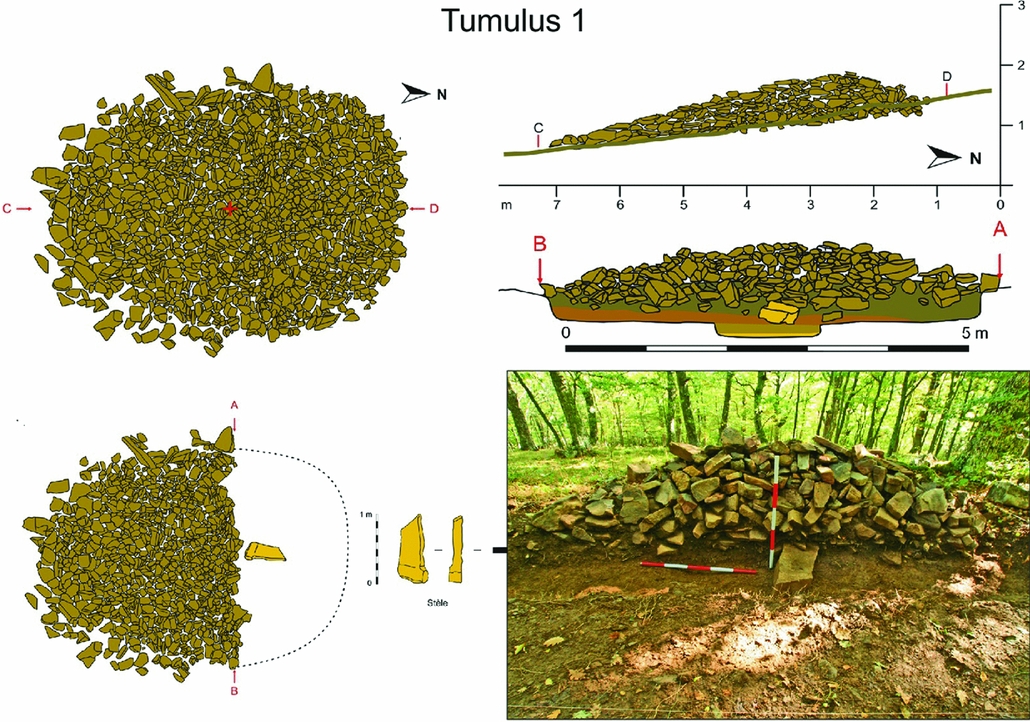

The surveys carried out as part of the ‘Monte Bernorio in its Environment’ project have located many sites scattered across the extensive mountainous territory. This includes the tumulus zone of Mata del Fraile, which comprises more than 50 tumuli. Between 2012 and 2015, the so-called tumulus 1—measuring 6m in diameter and preserved to a height of 1.1m, was excavated. Although completely empty, it yielded a carved stone cippus (pillar) in the middle (Figure 3). In 2016, the nearby smaller tumulus 2 was excavated. As with tumulus 1, it yielded no archaeological finds. The most plausible interpretation is that these empty tumuli were commemorative structures rather than regular tombs, acting as landmarks in the zones through which livestock were herded on the journey to summer pastures.

Figure 3. Photography and drawings of tumulus 1 of Mata del Fraile during the excavation, with the cippus in the middle (© IMBEAC; designed by A. Martínez-Velasco).

Materialities of imperial violence: the Cantabrian Wars

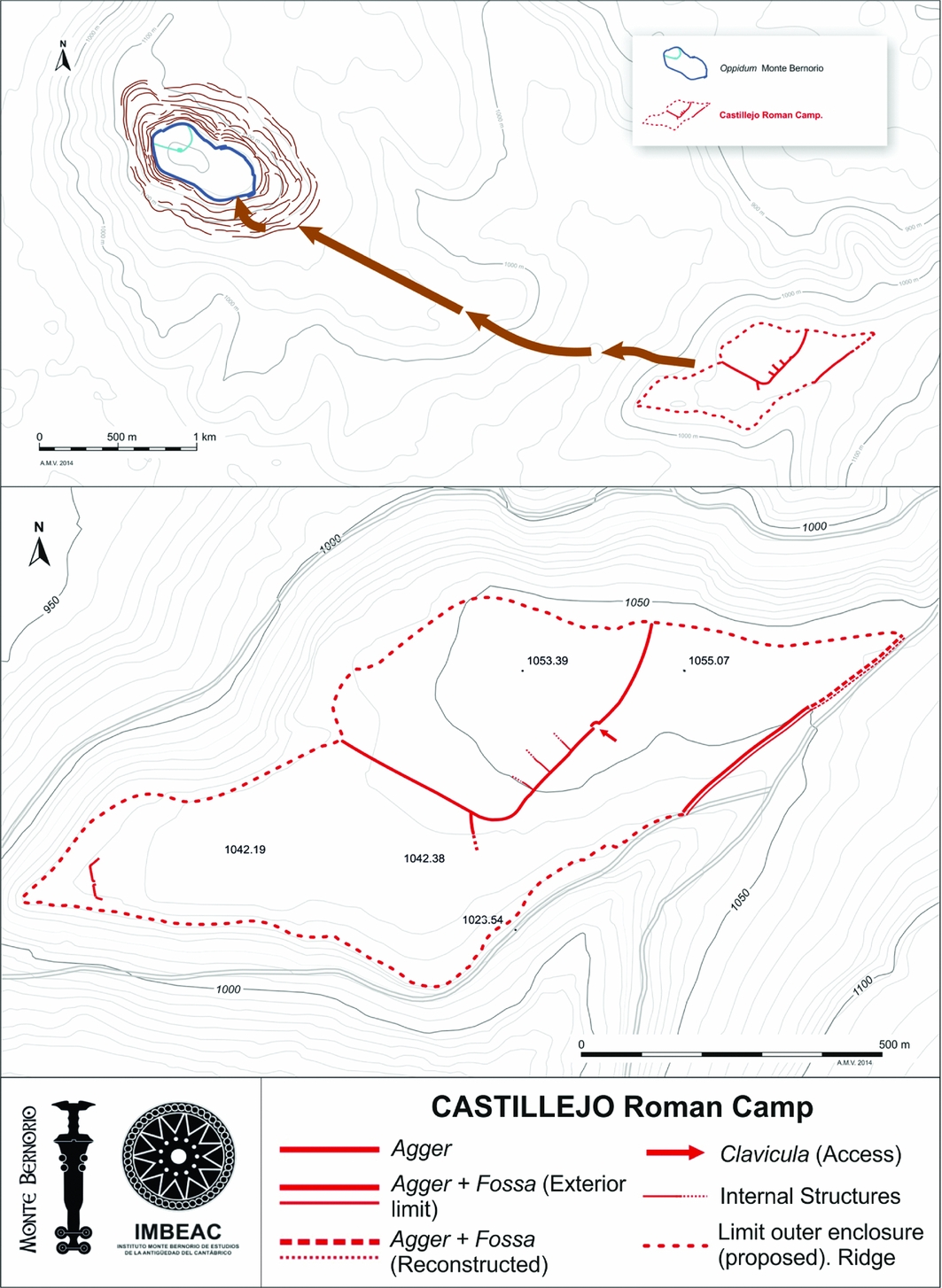

Archaeological evidence indicates attack by Roman troops destroyed Monte Bernorio during the Cantabrian Wars of Emperor Augustus (29–19 BC; see Camino et al. Reference Camino, Peralta and Torres-Martínez2015). In 2000, E. Peralta identified a large Roman military camp called ‘El Castillejo’, located immediately in front of the oppidum. Extending over 41ha, this structure is currently one of the biggest Roman camps known in Europe (Peralta Reference Peralta2004) (Figure 4). Excavations on Monte Bernorio itself have clearly established that the site was assaulted and destroyed by Roman forces (Fernández-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Torres-Martínez, Martínez-Velasco, Fernández-Götz and Roymans2018). Abundant ash, charcoal and burnt or carbonised artefacts within the archaeological layer mark the end of indigenous occupation. Roman objects, such as buckles, studs and rivets, have been recovered, along with fragments of possible pilum (javelin) heads. Studs from Roman caligae (hobnailed military sandals) were commonly found throughout the oppidum and its immediate surroundings, and two pieces of legionary soldiers’ finger rings were also discovered. These materials would have belonged to the legionary soldiers who attacked Monte Bernorio. Moreover, the presence of numerous projectiles confirms the use of artillery by the Roman army. The evidence clearly suggests that the oppidum fell after a battle on the southern side of Monte Bernorio (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Location and plan of the Roman military camp of ‘El Castillejo’ (© IMBEAC; designed by A. Martínez-Velasco & M. Galeano Prados).

Figure 5. Selection of Roman projectiles found at Monte Bernorio (© IMBEAC).

After the wars: the Roman settlement of Huerta Varona

After destruction of the oppidum, the Romans constructed a fort (castellum) on the north-western part of the mountain, which persisted for several decades. Apart from this fort, however, Monte Bernorio was never resettled and only became important again as a battlefield during the Spanish Civil War in 1936–1937.

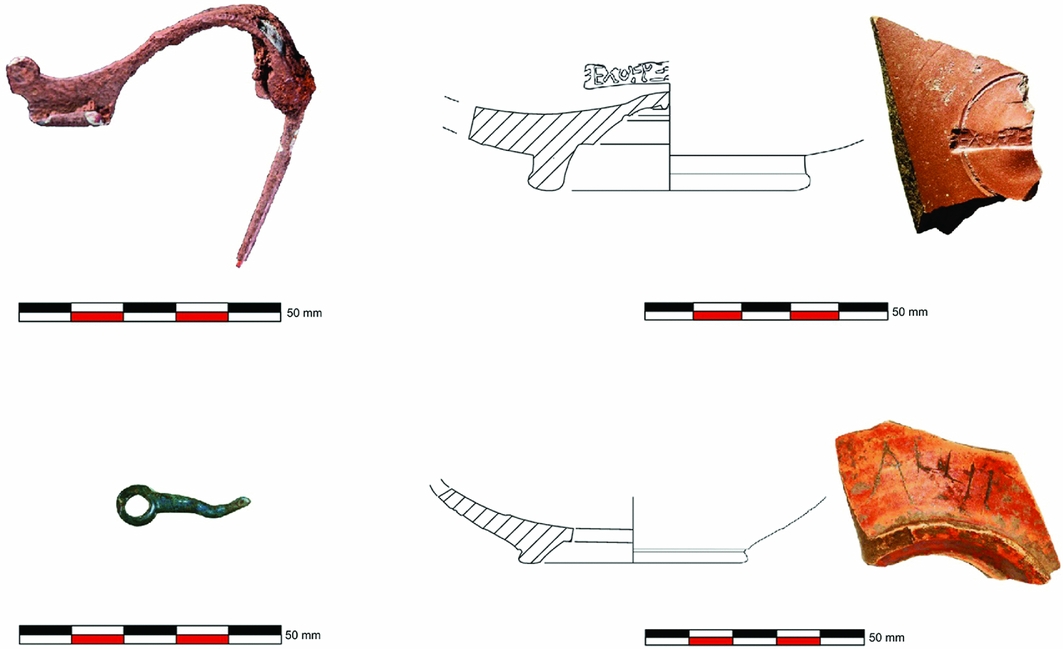

Interestingly, recent research at the site of Huerta Varona—located just a few kilometres away on the outskirts of the modern town of Aguilar de Campoo—confirms the existence of a significant Roman settlement (Torres-Martínez et al. Reference Torres-Martínez, Martínez-Velasco and Fernández-Götz2017). The site covers approximately 2ha. Since 2014, various excavation campaigns have been carried out here, complemented in 2016 by an extensive geophysical survey. Trenches revealed evidence for various stone buildings, as well as a large number of finds that date Huerta Varona to between the end of the first century BC and the fourth century AD. Particularly remarkable are the abundant pottery remains and a large quantity of oyster shells. Some metal objects, such as an Alesia-type fibula, clavi caligarii (iron hobnails) and weaponry fragments, suggest a Roman military origin for the settlement (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Huerta Varona: Alesia-type fibula, make-up palette and inscribed fragments of terra sigillata (© IMBEAC).

Geophysical survey revealed an extensive layout of structures over the whole area, with superimposed structures and a wide variety of buildings. As the site exceeded the limits of the surveyed area, this may be a vicus-type (small town) settlement. The site appears to have developed during, or soon after, the Cantabrian Wars, perhaps as a settlement for veterans, and continued to be inhabited for several centuries afterwards.