And so to my next NBC, the difficult second album, the sophomore slump. As an antidote to any jitters on my part, in this issue we tackle a range of books investigating creativity and innovation in the past. Innovation is enjoying something of a ‘moment’ in archaeological thought at present, with several large, multi-disciplinary projects underway in Europe and sessions devoted to the topic at major US and European conferences over the last few years. As with the current concentration on inequality, this interest can be traced to the social and political climate of the present and concerns over rapid technological change, economic growth and productivity. Innovation can be both productive and profoundly disruptive, and as such, it is of central concern in understanding social change in the past and predicting its effects in the future. The first four volumes discussed below deal directly with innovation, creativity and learning. The fifth, written by political scientist James C. Scott, invites us to consider the negative consequences of certain kinds of innovation and the implications for the sorts of complex societies that we live in today.

Creativity and innovations

Jørgensen, Lise Bender, Sofaer, Joanna & Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig (ed.). 2018. Creativity in the Bronze Age: understanding innovation in pottery, textile, and metalwork production. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 978-1-108-42136-2 £75.

Stockhammer, Phillipp W. & Maran, Joseph (ed.). 2017. Appropriating innovations: entangled knowledge in Eurasia 5000–1500 BCE. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-78570-724-7 £48.

Burmeister, Stefan & Bernbeck, Reinhard (ed.). 2017. The interplay of people and technologies: archaeological case studies on innovations (Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 43). Berlin: Topoi 978-3-9816751-8-4 €49.90.

Roddick, Andrew P. & Stahl, Ann B. (ed.). 2016. Knowledge in motion: constellations of learning across time and place. Tucson: University Press of Arizona; 978-0-8165-3260-5 $65.

Our first volume, Creativity in the Bronze Age: understanding innovation in pottery, textile and metalwork production, has the most tightly defined canvas, focusing on the European Bronze Age (in particular Central and Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia) and on the three material types described in the title. Still, this is plenty to be getting on with! The book has a complex structure, divided into three parts, the first two of which include groups of overview chapters, complemented by case studies in parts two and three. The introductory chapter sets out the theoretical approach adopted throughout the book, which emphasises the role of the material in the creation of objects. Rather than seeing creativity as the result of human agency alone, the authors use concepts such as entanglement to argue that creativity emerges through the interaction of material and human engagement. The possibilities afforded by specific materials therefore become central to understanding the process of innovation, and this is the focus of part one. Three chapters, each authored or co-authored by one of the editors, provide overviews of the innate properties of the material classes of interest (textiles, metals and clay) and the ways in which they could be used in human societies. These sit between a short introduction and a concluding chapter, written by all three editors, which draw out some of the major themes visible across the mediums discussed. Part two follows the same pattern, turning from properties to processes and production, with excellent summaries of the technical capabilities found across Europe over the course of the Bronze Age. The case studies have a wider author list and range in scale from individual sites, such as Bergerbrant's examination of spindle whorls at the Hungarian tell site of Százhalombatta-Földvár, to discussions of object classes at a pan-European scale, such as Appleby and Stig-Sorensen's treatment of moulds. Part three turns to the effects of made objects, what we might call the consumption of finished products, although the authors shy away from the term. Here the overview chapters are dispensed with in favour of a much larger collection of case studies, dealing with object categories (women's blouses, razors, bird-shaped ornaments) and cross-medium themes (cosmological motifs, right-left symmetry, patterned decoration) over wide regions as opposed to specific sites. A final conclusion emphasises dynamic tensions at the heart of creativity, between the material and the abstract idea and between the individual and social conventions.

There is much to admire in this book. The authorial involvement of the editors in many of the chapters lends a real sense of coherence, and this is followed through even in the case studies in which the editors were not directly involved. The link between high-level theory, material and case studies is maintained throughout. The overview chapters in parts one and two are comprehensive and well written, providing up-to-date summaries of the state of knowledge in the relevant areas. The book will thus serve as an excellent resource for those interested in the different artefact categories discussed. As an approach to creativity and innovation, however, the focus on specific materials and the creativity of the individual, while raising interesting and important points, comes at the cost of downplaying the wider social context. Who were the people doing the making and consuming in these societies, and how were the rules that their creativity maintained or transgressed enforced? How can we relate the wealth of innovations developed in the Bronze Age to changes in political economy and social complexity? To answer these sorts of questions we must move away from specific material engagements and creative moments to examine how and why innovations spread.

Two volumes emanating from major German projects take up this challenge. Appropriating innovations: entangled knowledge in Eurasia 5000–1500 BCE, emerging from a project based at Heidelberg, moves beyond Europe and the Bronze Age but retains a focus on specific sets of innovations. In their introductory chapter, Maran and Stockhammer take aim at the much-maligned concept of diffusion, which they see as the main explanatory mechanism up until the 1980s for the spread of ideas and technologies, and which still influences debate on this topic today. The volume is an attempt to move beyond this paradigm and the reactions to it. The authors argue that this can be achieved by a shift in emphasis from attempts to identify where and when particular technological advances occurred to how these innovations were “ingested by societies, and how this affected [. . .] the people constituting them” (p. 2). The 20 chapters that follow this (rather graphic) statement cover a huge geographic range, from China to Western Europe, and generally do a good job of sticking to the script. Bronze and other forms of metallurgy again feature heavily, as well as the cluster of new practices that make up the Secondary Products Revolution, the term first coined by Andrew Sherratt (Reference Sherratt, Hodder, Isaac and Hammond1981) to denote the exploitation of animals beyond primary consumption (meat), such as textile and milk production, traction and transport.

There is insufficient space to cover all the chapters here, so I will focus on two groups of papers covering very similar topics that turn up some interesting juxtapositions. In Maran's chapter we learn that the earliest evidence for wheeled vehicles in Europe comes almost exclusively from iconography, but that north of the Alps iconographic depictions diminish over time. Instead, we find components of vehicles deliberately deposited in wetland settings. Maran interprets this shift as the result of an increasing preponderance of wheeled vehicles, such that they become less prestigious, and therefore less worthy of depiction, but gain a new symbolic significance as parts of rituals associated with the protection of travel. Significantly, these practices cross-cut more traditionally defined ‘cultures’. In the north Caucasus, by contrast, Reinhold et al. show how the symbolic properties of wheeled vehicles could be adopted and adapted differently. In the mountainous Maikop culture region, traction animals developed symbolic value, as evidenced by bucrania recovered in burial contexts; while in the steppe, wagon burials become common at around the same time. They relate this distinction to differing ‘intellectual spheres’ in the two zones, the Maikop emphasising power, and the steppe dwellers emphasising mobility. Other chapters work together well to establish a consensus, such as those by Helwing and Frangipane on early metal production in South-west Asia, which both identify shifts towards prestige metal consumption by elites in the early third millennium BC. The loose affiliation between the different papers and the absence of a concluding chapter, or the sorts of short introductions and conclusions to sections used in Creativity in the Bronze Age, mean, however, that the reader is left to draw out any overarching implications on their own.

The second of the German volumes, The interplay of people and technologies: archaeological case studies on innovations, emanates from Berlin rather than Heidelberg, but, on the face of it, covers similar ground (and in fact several contributors overlap between the two books). This second volume, however, is more theoretically engaged and takes a deliberately critical approach throughout. In their introduction, Bernbeck and Burmeister take inspiration from Wolfgang Schivelbusch's (Reference Schivelbusch2000) study of the impact of railways in the nineteenth century, an innovation that not only changed the nature of transport, but also “affected perceptions of time, led to the appearance of new literary forms [and] the recognition of psychic trauma as a disease, among a myriad of other consequences” (p. 8). From this they develop a picture of innovation that foregrounds the unintended consequences of the uptake of new technologies and also their disruptive potential for established social norms, both areas largely untouched by the previous two volumes. The case-study chapters that follow again focus on Europe and the Near East, although North-east Africa and the North Caucasus get a look in, and on prehistoric and protohistoric periods.

There is less coherence in the range of topics and materials discussed than in the other German volume, and again no conclusion, but the longer chapters allow for more in-depth engagement with both the social context in which innovation occurred and the relevant archaeological literature. Innovations in this volume are also much more broadly conceived, with chapters on the process of sedentism in the Caucasus (Reinhold), the documentary gaze (Bernbeck) and repetitive mechanical reproduction (Pollock) at Uruk, treating each as innovations in their own right. Some chapters address more familiar topics but provide new insights. Meyer's discussion of iron smelting in north-central Europe, for example, demonstrates processes of regionalisation synchronous with the uptake of iron and relates these to the increasing ubiquity of the material in comparison to bronze, which required long-distance trade and facilitated wider communication networks. Dittrich uses the work of Gabriel Tarde to examine the process of Neolithisation in North Africa, arguing for a slow transition towards sedentism and the domestication of plants and animals through small-scale variations in everyday practices. The consequences of these minor changes to quotidian activities, however, were felt across society through changes to concepts of kinship, ancestry, the afterlife and local landscapes. An intriguing final chapter by de Zilva and Jung turns the innovation game on its head to investigate why copper technology did not take off in Central Europe until the Late Neolithic. They convincingly demonstrate that the technological capabilities of extraction and smelting were present from the Early Neolithic, and that social norms, including an aversion to new material forms and the conservatism of elites, must have been significant factors in inhibiting widespread copper use.

Our final book in this section is Knowledge in motion: constellations of learning across time and place, another edited volume arising from a series of meetings at TAG and SAA conferences in the USA. The dustjacket endorsement promises “quite a novel approach to issues that have preoccupied archaeologists for decades”, and the book itself does not disappoint. The approach in question draws heavily on the work of Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation (Reference Lave and Wenger1991), a key text in pedagogical literature that emphasises the social context of learning. In this framework, creativity occurs within communities of practice, connected groups of individuals working towards similar goals who share knowledge and innovation. These can themselves become parts of constellations of practice, higher level groupings with shared traits but limited actual contact. In their introductory chapter, Roddick and Stahl show how this approach can be adapted for archaeology, allowing for interpretations that incorporate relations of power and multiple scales of analysis. They argue that the focus of situated learning on the context in which learning and knowledge transmission takes place plays to archaeology's strengths in understanding the spatial patterning of material culture, both within sites and across larger regions.

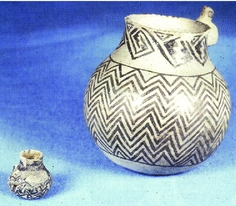

The following nine chapters are again case studies from disparate parts of the world, with contributions from Africa and Central and South America predominating, all of which make use of the situated learning paradigm. The variation in the scale and topic is impressive and showcases the potential of this approach well. Highlights include Crown's chapter on pottery production in the American Southwest, which argues that apprentice potters were permitted to take certain ceramic classes but were excluded from others. She speculates that skilled potters may have restricted knowledge transfer until some form of initiation had taken place. In his chapter, Sassaman works at the scale of the entire US Gulf Coast. He links the locations of cemeteries, settlements and monuments to solar alignments, and the dispersal of soapstone to argue for an emergent constellation of practice designed to make sense of sea-level changes over 1500 years. The shared experience of rising seas and forced inland movement “invited connections to the high, dry interior lands” (p. 290), with repercussions for material culture, ritual and settlement practices. Other chapters consider intermediate scales, such as Blair's excellent investigation of glass bead production in seventeenth-century Florida, or Roddick's discussion of pottery practices and power relations in the Lake Titicaca Basin. Throughout, the emphasis on the context of learning proves a productive avenue for thinking through the creative process and the movement of innovations and skill.

The four books discussed here demonstrate the breadth and depth of research currently being undertaken in the field of creativity and innovation. Placing them side by side, it is clear that a series of productive tensions are emerging. There is still justifiable interest in large-scale, big-picture questions relating to the spread of major innovations that shape our modern world—including agriculture, the wheel, aspects of metallurgy—but at the same time, a growing recognition that the movement of technology is a social process, reliant on individuals changing what they do. Creativity is also recognised as entangled, both with the materials and mediums upon which it is practised and the social world in which it occurs. Archaeology's material foundations, long time-depth and multi-scalar approach make it uniquely positioned to investigate these processes, and these books evidence the progress being made.

Power from the people

Scott, James C.. 2017. Against the grain: a deep history of the earliest states. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 978-0-300-18291-0 $26.

Our final book is political scientist James C. Scott's Against the grain: a deep history of the earliest states. In previous books, such as The art of not being governed (Reference Scott2010) and Seeing like a state (1999), Scott has developed a highly negative view of state power, arguing that modern states are far from the benign ‘civilising’ force some take them to be. Here, he turns his attention to the origins of the state, marshalling an impressive array of archaeological data and interpretation to argue that their emergence was built on violence and repression. Geographically, the book focuses on southern Mesopotamia, which Scott argues features the earliest pristine (i.e. autochthonous) state development in the world. Historically, we venture much further back than most discussions of the emergence of complex societies, beginning with the first use of fire by hominids some 400000 years ago, which is argued to be the moment our ancestors began to transform the natural world. From these beginnings, hunter-gatherer communities developed, reliant on diverse environments and managing a range of resources to sustain small but healthy societies. For Scott, the trouble starts with farming, which narrowed the range of resources available, required more labour and meant human groups had to stay in one place, resulting in restricted diets, increases in disease and higher mortality. For these reasons, the shift to farming during the Neolithic was far from a revolution, taking place over millennia, with many communities retaining aspects of hunter-gathering practices. The emergence of states themselves occurred some 4000 years after the first farming, and came about through the development of mechanisms for controlling resources. Scott makes a convincing case for the importance of grain as the staple produce for these early states. Unlike tubers or root vegetables, grain grows above ground and must be harvested at specific points in the year, making it difficult to avoid taxation, and can be stored for long periods before being redistributed. Once such systems were in place, the control of labour became paramount. Bureaucracy, slavery and warfare all played their part as coercive strategies for disciplining non-elite parts of society. A corollary of this reliance on violence is that states were fragile, prone to collapse as a result of relatively small changes in climate, environmental over-exploitation and both internal and external conflict. Given the conditions under which much of the population lived within states, however, collapse was perhaps no bad thing! Finally, early states were also reliant on non-state societies on their peripheries, ‘barbarians’ who alternated between trading and raiding to exploit the agrarian wealth of their neighbours.

As Scott himself is quick to point out, there is no new archaeological material in this book—the interpretations of hunter-gatherer, Neolithic farmers and early states have all been made by archaeologists and anthropologists over the last 50 years. What is new is the drawing together of all of this information into a single overarching narrative, one which has profound implications for the way that we think about the emergence of complex societies. As with any grand narrative, one can quibble with aspects of the data, and as with any polemic, the argument is rather one-sided. Is it really true that states are entirely coercive and incapable of producing positive outcomes? Was life in hunter-gatherer or barbarian societies really so rosy? The value of the book, however, is precisely in the sorts of provocative questions it raises and the debates it will spark. Scott brings archaeology into one of the most important insights of his wider project, that states are neither inevitable nor neutral. In doing so, he has created a space in which archaeology becomes relevant for current political concerns, and for this reason alone his book should be widely read within our community.