This NBC considers a selection of volumes that speak to one of humanity's most significant themes: how we express ourselves, in both life and death. In this issue, we learn how the dead were represented in Bronze Age Arabia (Kimberly D. Williams & Lesley A. Gregoricka) and Bronze Age Laconia (Chrysanthi Gallou), and how the dead—in the form of shades or ghosts—were depicted in ancient Rome (Patrick R. Crowley). Following that, we turn to how people have communicated with each other in script, images or marks. Katarzyna Mikulska and Jerome A. Offner consider the challenges of deciphering Mesoamerican Indigenous communication systems, while Eleanor Robson traces the ancient knowledge networks of Assyria and Babylonia through social geographies. Graffiti is the subject of Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis's edited volume, which charts the ways in which people have left their mark at pilgrimage sites in the Middle Nile region. In their different ways, each volume emphasises the challenges of interpretation and the complex methodologies required to read across the centuries and understand communications in the past, as well as the need to revisit evidence with alternative approaches and perspectives.

The contributors to Mortuary and bioarchaeological perspectives on Bronze Age Arabia address the funerary archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula, an area of the Near East that has not benefited from the extensive archaeological work undertaken in other parts of the wider region, such as Anatolia, Mesopotamia and the Southern Levant. For an area with such a visible mortuary record, surprisingly little research has been published on the subject. Kimberley Williams and Lesley Gregoricka's volume aims to remedy this. Along with 14 international contributors, the editors bring together a broad range of evidence that aims to understand population dynamics, identity, health and foodways; it is a work that certainly challenges the common view of the Bronze Age in the Arabian Peninsula as a backwater.

As Williams and Gregoricka highlight in their introductory chapter, archaeologists and bioarchaeologists face a range of hurdles in interpreting the archaeological record of the Arabian Peninsula, including the poor preservation of faunal material and the persistent reuse of monuments. Despite these challenges, the volume's 12 chapters bring interdisciplinary and international perspectives to bear on the mortuary record of the region. Focusing predominantly on the Early Bronze Age, the volume also takes in the transition from the Neolithic and continues on to the Pre-Islamic period. The editors open the volume with a brief history of mortuary archaeology and bioarchaeology in the region; they outline key periods and themes such as the Hafit to Umm an-Nar transition, communal tomb use, spatiality and variation of tombs, and call for the initiation of “a broader dialogue on the growing importance of bioarchaeology and mortuary archaeology in this region” (p. 12).

The volume falls naturally into two broad sections. Part I—‘Mortuary transitions’—considers the archaeology of mortuary practices including the social implications of their increasing complexity (Munoz); typological changes (Cuttler & Izquierdo Zamora); transitions in mortuary ritual in the third millennium BC (Williams & Gregoricka; Cable); continuity and discontinuity in graveyards (Gernez & Giraud); and the structural evolution of monumental burials (Bortolini). Part II—‘Evidence from the bones’—turns to the bioarchaeological evidence, as the name suggests. Contributions to this section deal variously with animal bone deposits in mortuary contexts (Weber et al.); demographic structure and collective burial (Martin et al.); temporal trends (Gregoricka); age and masculinity (Boutin & Porter); and, finally, a concluding chapter by Peter Magee that responds to the contributions.

The chapters all have much to offer, but here I focus on just two as space permits. Olivia Munoz's chapter offers an interesting and broad view of the increasing complexity of mortuary practice from the Late Neolithic, when the dead were buried in simple pits close to domestic areas, through the Early Bronze Age Hafit-type cairns, circular stone structures built above ground and visible in the landscape, to Umm an-Nar burials, which became increasingly monumental over time. Munoz considers the social changes that lay behind these ever more complex mortuary practices, arguing that these tombs reflect growing social differentiation, the emergence of specialist craft production and a diversification of materials used. Munoz notes the increase in collective tombs and speculates on whether this phenomenon may have been “an ideological response to the destabilizing character of growing social inequalities among the living by promoting a group identity and principles of equality between individuals in death” (p. 31).

Peter Magee's concluding discussion draws out the major themes that emerge from the volume and identifies some of the challenges that persist. Magee stresses that one of the key results to emerge from the volume is that the archaeological evidence supports a blurring of the distinctions between material culture phases, both in terms of chronology and internal consistency, and that social concepts of community and individual identity were shifting, being challenged, reaffirmed and ultimately transformed. The author emphasises what seems clear from this study, that the volume represents “a milestone in our understanding of the mortuary archaeology of ancient Arabia” (p. 249) and that such studies should be integrated increasingly into broader studies of the wider region to ensure Arabia does not continue to be marginalised in Near Eastern studies.

Like Williams and Gregoricka's volume, Death in Mycenaean Laconia: a silent place also fills a lacuna in research, this time in the south-eastern Peloponnese. Chrysanthi Gallou undertakes a comprehensive study of Late Bronze Age funerary archaeology to challenge a long-held assumption that Laconia was abandoned after the decline of Mycenaean palaces. Gallou finds instead a continuity of mortuary traditions from the Early and Middle Bronze Age to the Later Bronze Age. Combining archaeological evidence for burial architecture, funerary and post-funerary rites and material culture with the social, political and economic history of Laconia in the Late Bronze Age, Gallou is able to trace the expression of tradition and identity throughout the Bronze Age.

Drawing on a range of previous studies, the introduction outlines previous research and presents a description of the topographical and geological setting of Laconia. It also introduces the case study of the chamber tombs at Epidavros Limera, excavated by the Greek Ministry of Culture in the 1930s and 1950s and published here for the first time. Epidavros Limera is identified, using ancient text sources, as a settlement not of Lakedaimonians, but of Epidaurians from the Argolid. Whatever the nature of its foundation, Gallou points to evidence which shows that Epidavros Limera may have been occupied since the Final Neolithic (c. 4500–3200 BC), was a thriving harbour site from the third millennium BC and reached the peak of its expansion in the Early Helladic II period c. 2200–2000 BC.

The following chapters deal respectively with graves and burial contexts—both those that are excavated and those that are reported but unexcavated; burial architecture; burial customs and rites; and pottery. Chapter 1, the corpus of graves and burials, lists sites by tomb type (tholos, chamber tombs, built chamber tombs, simple graves and unspecified) and by geographic area. The data are presented as detailed catalogue entries. The recorded sites also include submerged chamber tombs at Pavlopetri, and together this corpus represents a significant amount of data collection and research. Analysis of the tomb types follows in Chapter 2, which presents the various architectural forms that are associated with each period, from the Late Helladic to the Late Bronze Age.

In Chapter 3, Gallou turns to the ritual practices associated with death and burial in Mycenaean Laconia. Here the evidence for preparation of the body, mourning, funeral processions, burial rites at the grave (in particular relating to deposition of grave goods), secondary funeral rites—involving ceremonial detachment and repositioning of the skull—and reuse of tombs are investigated.

The volume closes by drawing together the evidence and synthesising the results of this substantial project. Gallou argues that there is little to suggest that Laconia was abandoned after the decline of the Mycenaean palaces; in fact, Laconia provides significant evidence that allows us to trace mortuary practices from the transitional Middle Helladic to the Late Helladic period (early to mid second millennium BC) to the end of the post-palatial era and the beginning of the Early Iron Age (late second millennium BC). This period witnessed innovations, extended exchange networks and the rise and fall of palatial powers, some of which can be seen reflected in mortuary practices.

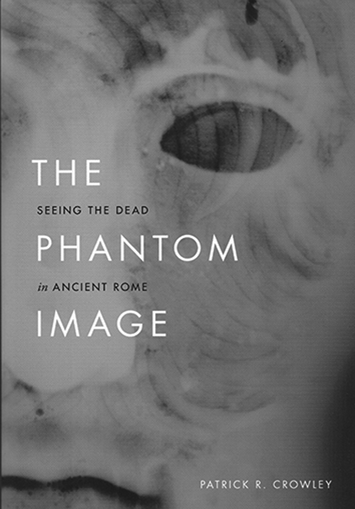

Whereas the previous two volumes are concerned with laying the dead to rest, Patrick Crowley's volume examines the dead amongst the living, through the phenomenology of Roman umbrae (shades or ghosts). The volume explores, in particular, the depiction of ghosts in the Roman world, how they were illustrated and what they reveal about ways of seeing, representation and modalities of belief in the ancient world. Drawing on funerary monuments, tomb paintings, mythological sarcophagi and floor mosaics, largely from mortuary contexts in Rome, Crowley explores the concept of ghosts in the ancient world and how this is evidenced in imagery. Crowley eschews the traditional approach that might tend to consider depictions of ghosts as material expressions of belief; rather, the volume explores the relationship between the image of the ghost and the historical ontology of umbrae and the ways that the image may have been experienced. Chapter 1 focuses on the depiction of ghosts as pictures and through pictures. This is expanded in Chapter 2 to move from the practical matter of how Roman artists were able to depict the ethereal using the material, to a consideration of ways of representing an invisible underworld. In this chapter, Crowley asserts that ancient visualisations of the underworld used techniques such as the ‘interstitial sublime’; the sublime is viewed as the meeting point of aesthetic and religious understanding, after the Homeric tradition. The interstitial sublime, then, represents the point of human encounter with the divine, which Porter describes as a “mutual point of failure and ecstasy” (Reference Porter, Sluiter and Rosen2012: 66). Using the limits of the field of vision and dissolving them to suggest the potential for exceeding these boundaries—particularly to access the cavernous depths of Hades—offered a way to represent the immortal realm. The chapter includes extensive discussion of chorography and perspective and an exploration of the phenomenology of funerary architecture, in particular sepulchral chambers as analogies for journeys to the underworld. This section includes analysis of mosaic, stucco relief, wall painting, architectural features, the use of colour and the impact of these media on the embodied experience of mourners. Crowley sees the tomb as an “evocative space that in many ways must have resembled the imaginative space of the underworld” (p. 115).

The iconography of the shrouded ghost provides the focus for Chapter 3 in which the iconography of shrouds, veils and the chlamys (a cloak) is considered through imagery featuring the ghosts of Agamemnon, Alcestis and Protesilaus, all of whom are depicted shrouded, often with their heads and sometimes faces covered. The shroud is used here in an inversion of its traditional role—rather than serving to conceal, it reveals the ghost. Chapter 4 turns to the question of belief, focusing on depictions of the doubting apostle, Thomas. In this chapter, Crowley explores the use of imagery in representations of this Gospel story, such as that on a late fourth-century sarcophagus, and the ways in which the depictions address broader questions about the materiality of Christ in his encounter with Thomas after the crucifixion. Thomas's need for tactile confirmation of the reality of Jesus forms the basis of the reality of the resurrection—Thomas needed reassurance that Jesus was not simply a ghost.

The Epilogue concludes that “the more the very existence of ghosts was debated in ancient discourses, the more they appear in depictions in tomb painting, floor mosaics, and mythological sarcophagi” (p. 228). For Crowley, however, this is more than a straightforward mirroring of belief, instead it reflects “the imagistic relays that connect the visual operations of seeing and the visual operations of depiction” (p. 229).

Communicating in the ancient world

Our next three volumes are concerned with communications between the living, and, more broadly, how we can approach an understanding of ancient systems of communication while so far removed from the peoples who used them.

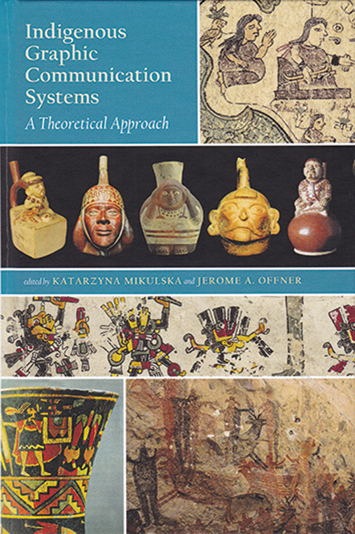

Mikulska and Offner's volume aims to challenge longstanding views of communication systems in Central Mesoamerica and Andean South America, namely that only a few pre-writing communication systems existed in this region and none that could be considered a true writing system. Contributors to this volume have come together to attempt “comprehension of the indigenous graphic communication systems of the Americas” (p. 16), an area of investigation that the editors feel has thus far eluded theoretical investigation. This volume, then, aims to open a new dialogue about what writing actually is, from a global perspective.

The book boasts 14 international contributors, representing balanced transatlantic collaboration, across its four sections: ‘Semasiographs and semasiography’, a definition of which is conveying meaning through signs, pictures or icons (p. 182); ‘Metaphor orality and space’; ‘Reconnoitering the periphery’; and ‘Going into detail’. The introduction by Katarzyna Mikulska provides a detailed history of the problems with the study of Indigenous American graphic expression and a theoretical exploration of what constitutes writing. Mikulska points to pioneering recent studies by Elizabeth Hill Boone and Gary Urton (Reference Boon and Urton2012) and Stephen Houston (Reference Houston2008) that have begun to advance the subject, showing how this volume builds on that work.

Wright-Carr's contribution presents a theoretical framework that can be used to classify central Mexican graphic signs or graphs. Using studies of four graphs from pre-Hispanic Mexica sculpture and a colonial-period Otomi codex, the author identifies a dual function of these visual languages. The Tizoc stone and the Huichapan Codex reveal that graphs could be verbalised by any of the Indigenous groups who shared the culture of the region, and the same signs could represent linguistic structures in a specific language, essentially creating glottographic (language-based or vocalised) signs.

Jerome Offner's chapter considers the problems of an occidental approach to graphic communication systems that originated in different social and cultural processes. The chapter draws out the importance of the underpinning principles of a graphic communication system in understanding the nuance and context of the graphics. Examining the Nahua graphic communication of a pre-Columbian Mesoamerica region, Offner shows how a full understanding of the graphics in the Codex Xolotl requires cultural knowledge of the underpinning political organisation and kinship. Offner finds that “a culturally embedded and expected semasiographic operative principle within that system united orality, performance, and graphic expression into a robust system for transmitting information across time and space and across generations” (p. 198), but it depended on cultural knowledge to be understood in its proper context.

The afterword, also by Offner, returns to the challenges of approaching Mesoamerican Indigenous graphic systems through a Western lens. Offner reflects on the new perspectives that the contributions bring to this topic and how they have helped to narrow “the gulf of incomprehension between indigenous and Western concepts of history, historiography, and social and political analysis” (p. 378).

Despite the wealth of studies of cuneiform scripts, beginning with the earliest days of archaeological research, the next volume demonstrates a fresh approach and perspective on these communication systems. In Ancient knowledge networks: a social geography of cuneiform scholarship in first-millennium Assyria and Babylonia, Eleanor Robson focuses on Assyrian and Babylonian networks of knowledge to understand the transfer of ideas in a book that the author describes as “an experiment in writing about ‘Mesopotamian science’” (p. 1). The volume attempts to move away from the use of value-laden labels that have in the past defined people and ideas through preconceived and sometimes anachronistic concepts, instead considering the collective ‘scholarship’ of cuneiform culture. Chapter 2 challenges the lack of historicisation, which has resulted in an idea of universality that has masked the diversity of geographic and chronological contexts of Assyrian and Babylonian intellectual culture. Robson deconstructs the canonised idea of a “stream of tradition” (p. 26), and suggests new methodologies and sources that allow a more detailed historicisation and understanding of the subject, such as revisiting the archaeological context of the Kouyunjik tablets, and the tablets from Late Babylonian Uruk.

Chapter 3 considers Neo-Assyrian court scholarship by taking a multi-scalar geographical approach to the associated people, gods and locations. This ranges from the movements of people and ideas between cities to the urban planning and architecture that framed life at the court. The chapter covers an impressive five centuries of continuity and change culminating in the collapse of the court system and how this was related to the cult of Nabu—the god of wisdom—and a reduction in royal scholarship. The relationship between Nabu and the kings of Babylonia is explored further in Chapter 5.

In Chapter 6, Robson considers scholars in social spaces other than the royal court; these are traced through administrative archives and tablets from temples and domestic contexts and with a view to understanding how scholarly networks survived the independence revolts c. 500 BC. The results reveal greater complexity in the relationships between scholars and temples than previously understood, but still show that intra-Babylonian networks were reduced to regional hubs at this time.

Robson's Social geography of cuneiform scholarship aims to “put the people and the objects back into the picture” and in doing so “to give that picture life and movement, depth and texture” (p. 43). This is an engaging volume that takes an original approach to understanding the agents of knowledge networks and the social, geographical and cultural factors that shaped them.

Continuing the theme of communication, Graffiti as devotion along the Nile and beyond considers the unsanctioned textual or figural graffiti of the Middle Nile region, between Aswan and Khartoum, from the third millennium BC to the medieval period. This edited volume is the accompanying publication to the exhibition of the same name on display at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan, from August 2019 to March 2020.

After the foreword, the contributions begin with a cultural history of Kush by one of the editors, Geoff Emberling. This provides an introduction to the religion of the Kush Empire—the earliest such polity of sub-Saharan Africa, which thrived between c. 2000 BC and AD 300—and explores the relationship between Kush and Egypt. This discussion offers a context for the historical trends that are evident in the graffiti of the region including the importance of pilgrimage and graffiti in the Kushite religion and the endurance of these practices in the medieval period in the Christian kingdoms of Nubia. The chapter includes an excursus by editor Suzanne Davis that describes the Meroitic graffiti at the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat es-Sufra, a major religious complex dating from the Napatan period (c. 1100–300 BC), but with the majority of activity occurring in the Meroitic period (c. 300 BC–AD 300). The graffiti at the site can be categorised as inscriptions, pictures and markings, and includes inscriptions in Meroitic, Latin, Old Nubian, Greek and Arabic scripts and a vast range of symbols including animals, geometric patterns, religious symbols, plants, humans, hybrid creatures and architecture.

Chapter 2, by editors Davis and Emberling, focuses on the graffiti at the funerary temple at El-Kurru. Here, the graffiti in the temple is associated both in theme and location with ritual practice, and the act of inscribing graffiti was likely to have been part of the process of pilgrimage and private devotion. In Chapter 3, Bruce Beyer Williams considers what a reading of the types of boat in graffiti on the El-Kurru pyramid can reveal about navigation on the Nile in the Christian period. Suzanne Davis explores the conservation and documentation of graffiti in Chapter 4, which again focuses on El-Kurru. This details various threats to the legibility of the graffiti, possible methods of preserving it and careful documentation using reflectance transformation imaging to reveal barely legible surface detail and to record examples before they further deteriorate. The volume includes an illustrated catalogue of selected graffiti from El-Kurru with a location plan. The contributions are supported by beautifully reproduced colour images that allow full appreciation of the preservation of the graffiti.

The geographic outlier is Chapter 8, by Rebecca Benefiel, on the graffiti of Pompeii, which reveals a snapshot of the more prosaic origins of 11 000+ texts and images etched onto the walls of the city's buildings. Whereas the inscriptions at pilgrimage sites remain as testament to the gravity of the occasion, Benefiel finds at Pompeii a selection of light-hearted greetings, messages of love, poetry, images of boats and gladiators or figured images. These reflect the everyday life and concerns of Pompeiians.

Perhaps understanding the everyday is exactly the value of being able to read and interpret ancient communications. The volumes reviewed in this NBC all caution against simplistic readings of past communication, and each offers a new methodology and invites us to look again at how we read and interpret the words and images created by ancient peoples. The effort is rewarded, for whether they offer a window on the process of mourning, grief, devotion, the artistic struggles to represent the metaphysical, or whether they simply tell us that “Methe from Atella, the slave of Cominia, loves Chrestus” (Benefiel p. 123), ancient communications provide a glimpse into the ways in which individuals in the past, spoke across time and space—to each other and to us.

This list includes all books received between 1 November 2020 and 31 December 2020. Those featuring at the beginning of New Book Chronicle have, however, not been duplicated in this list. The listing of a book in this chronicle does not preclude its subsequent review in Antiquity.