A recent study of the Quranwala Zone (QZ) of the north-west sub-Himalayas, India, presents evidence for anthropic activity during the Pliocene that includes a number of stone tools found in association with fossil animal bones with cut marks. Based on the date of the Pliocene rock outcrop, the tools and bones are suggested to date from 2.6 Ma (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016). There is, however, a question mark over the context of these tools within an outcrop of Pliocene rocks and, hence, over the date of these tools and the fossil bones. The trench from which they were excavated at Masol 2 (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016: fig. 3) lies in a depression at the bottom of a slope; the description provided in section 2 of the paper by Gaillard et al. (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016) suggests that the stone tools may not have been in situ within the Pliocene levels, but had accumulated there and were mixed with the fragments of fossil bone due to geological processes. Moreover, many of the stone tools, such as the ‘simple choppers’ found in association with the fossil animal bones (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016: figs 6, 8, 9), are usually found on much more recent sites and are therefore unlikely to date from 2.6 Ma.

Gaillard et al. (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016) provide no direct evidence, such as deep excavations or OSL dating, to prove that the stone tools and fossil bones were in situ within the Pliocene rock outcrop. More generally, any in situ evidence for stone-tool-using hominins in the sub-Himalayas could only derive from after the hills had more or less achieved their present morphology. All the tributaries of the Rivers Satluj or Ghagar were created during the uplift of the hills, with further entrenchment and subsequent changes in their courses due to tectonic activity. The lowest terraces are the youngest and were created during the terminal Pleistocene to mid Holocene. Previous work by geoarchaeologists indicates that Stone Age sites, with Soanian-type stone tools, are always found in close proximity to water courses, generally on these river terraces. The stone tools reported by Gaillard et al. from Masol were found in the vicinity of the Patiali Rao River, and should therefore post-date the formation of the landforms.

A Pliocene date is also called into question by the nature of the claimed association between the tools and the fossil bones. In their conclusion, Gaillard et al. (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016: 356) state:

These tools appear to be adapted to the size of the vertebrates present in the QZ and on the outcrops where they occur together. This systematic co-occurrence may indicate that some of the artefacts, especially the simple choppers, so far unknown in the Siwalik frontal range, may be contemporaneous with these terrestrial and fresh water vertebrates, such as the mid-size bovid, of which a bone bears cut marks.

Firstly, the statement that simple choppers are ‘unknown’ in the Siwalik frontal range is incorrect. Such tools are found on a number of sites in neighbouring regions where they are known—and have been for some time—as ‘Soanian’ tools, and are associated with the post-boulder conglomerates of late Mid Pleistocene date (Chauhan Reference Chauhan2007; Nanda Reference Nanda2013: fig. 2). The claim that these tools represent a distinct ‘Masol industry’, limited to the QZ and distinct from the Soanian, is repeated in another publication by the same team (Dambricourt Malassé et al. Reference Dambricourt Malassé, Singh, Karir, Gaillard, Bhardwaj, Moigne, Abdessadok, Sao, Gargani, Tudryn, Calligaro, Kaur, Pal and Hazarika2016: 313). In fact, the descriptions of the stone tools from the Masol region (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016: 343–54) reveal nothing new or different from the tools found elsewhere in the sub-Himalayas. Secondly, Gaillard et al. (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016: 356) state that “the simple choppers and flakes collected in the trial trench B1 at Masol 2 and on the outcrops of the QZ could be associated with the scavenging activity evidenced 200m apart at Masol 1”. What sort of scavenging activity might have been separated by 200m? Thirdly, fig. 8 of Dambricourt Malassé et al. (Reference Dambricourt Malassé, Singh, Karir, Gaillard, Bhardwaj, Moigne, Abdessadok, Sao, Gargani, Tudryn, Calligaro, Kaur, Pal and Hazarika2016) shows a chopper that appears to have fallen from the surface of a small butte and to have been deposited below on the butte's wall; as such, the chopper is not in situ. The explorers also observed several stone tools scattered below and around the butte. It is possible that, a few thousand years ago, the butte had a larger planar surface where people made and used stone tools; subsequent erosion reduced the area of the butte, with the tools redeposited below.

Hence, the alleged uniqueness of the tools, their stratigraphic context and their association with the fossil bones are all open to question.

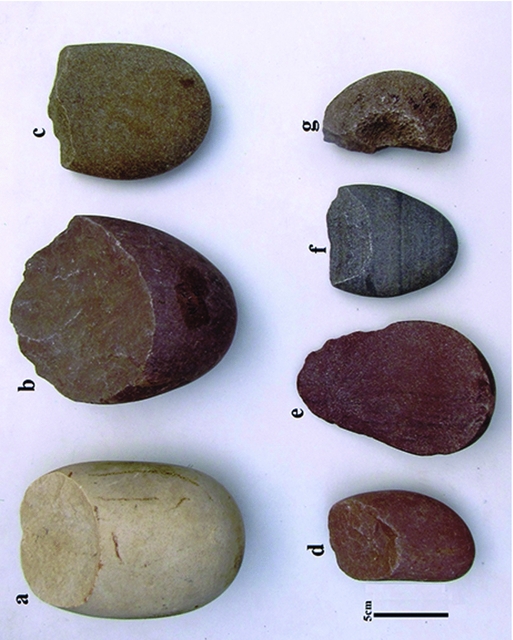

In fact, many similar stone tools have been recently discovered from mid-Holocene sites in the region (Figures 1 & 2). Most of these tools were recovered from mid-Holocene terraces on the River Satluj and its tributaries; OSL dating confirms the age of these terraces and the associated stone tools. For example, a terrace of the River Satluj at Nangal has been OSL-dated to the mid-Holocene (Table 1). Figure 2 (a–e) shows tools recovered from the terrace; the raw material was collected from the boulder conglomerates. A rich lithic assemblage (Figure 2: f–g) was recovered from another mid-Holocene site named Jandori-1 (Soni & Soni Reference Soni and Soni2013).

Figure 1. Map showing important mid-Holocene sites that yielded Soanian and other tool types.

Figure 2. a, b, d) Simple choppers from Nangal terrace dated to the mid Holocene; c) used end-chopper from Nangal terrace; e) elongated end-chopper on flake with used working edge from Nangal terrace; f) simple chopper from the mid-Holocene site Jandori-1; g) half ring-stone from Jandori-1.

Table 1. OSL dating of soil samples of mud deposition underlying the stone tools on the terrace NGT-2 of the River Satluj at Nangal. Material-sediment sample: mineral used—quartz, size: 90–125 micrometre SAR protocol.

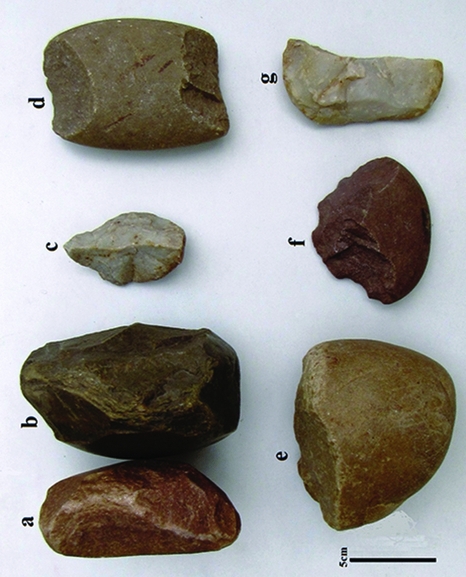

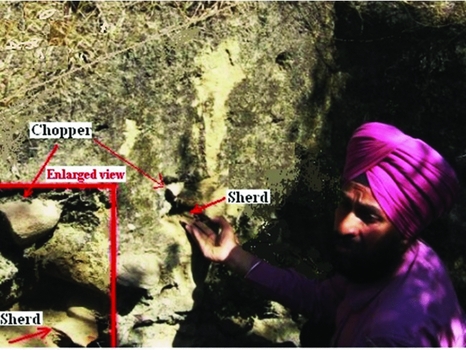

A probable mid-Holocene date for Gaillard et al.’s (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016) so-called ‘Masol-type’ stone tools is further suggested by the presence of similar tools at late Harappan sites such as Bara and Dher Majra of District Ropar, Punjab (Soni & Soni Reference Soni and Soni2012). A selection of stone tools from these sites is shown in Figures 3 and 4 respectively. Such tools have also been recovered from the excavated context of a confirmed late Harappan/mid-Holocene site in Himachal Pradesh (Soni & Soni Reference Soni and Soni2012). The in situ presence of stone tools with pottery is shown in Figure 5, and a selection of tools from this excavated site is shown in Figure 6. In summary, the ‘simple choppers’ that Gaillard et al. (Reference Gaillard, Singh, Malassé, Bhardwaj, Karir, Kaur, Pal, Moigne, Sao, Abdessadok, Gargani and Tudryn2016) claim to be associated with 2.6 Ma anthropic activity and present only in the Siwalik frontal range are, in fact, found widely in mid-Holocene contexts. This strongly suggests that none of the stone tools recovered from Masol is associated with anthropic activity of a late Pliocene date. As such, there is no evidence on which to argue for the presence of hominins in this region during the late Pliocene. Currently, there is nothing to suggest that stone-tool-using humans were present in the sub-Himalayas earlier than the terminal Pleistocene to mid Holocene.

Figure 3. Choppers recovered from a confirmed late Harappan/mid-Holocene site at Bara: a) side-chopper; b) end chopper; c–d) simple choppers.

Figure 4. Stone tools from late Harappan site Dher Majra: a–b) chopping tools showing battered edges; c) pointed unifacial prismatic core; d) bi-ended cutting tool; e) end-chopper with abraded edge; f) triangular chopper; g) unifacial end-scraper.

Figure 5. In situ chopper and a late Harappan potsherd being recovered from the excavation of Jandori-6 by Anujot Singh Soni.

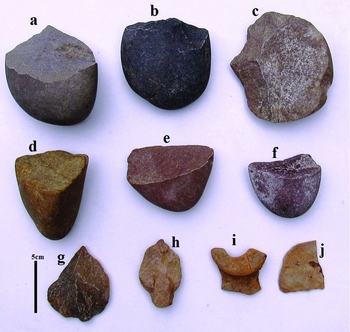

Figure 6. Material found from the excavation of Jandori-6: a) pointed chopper; b) end-chopper; c) pointed side-chopper on a thick first flake; d–f) simple choppers; g) Levalloisian point; h) projectile point; i–j) late Harappan potsherds.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to K.C. Nauryal for inviting us to the late Harappan mound Bara, to V. Shinde for identifying the pottery recovered from the excavation, and to A.S.I. New Delhi for granting us permission for the excavation of the Jandori site and for allowing us to explore the Punjab and Himachal Pradesh regions at various times.