Some words are more difficult to (learn to) spell than others. These are generally words in which the association between phonemes and graphemes is not straightforward. Difficulty increases when the words sound the same but the spelling differs due to lexical differences (e.g., English carrot and carat) or morphological inflections (e.g., French “ami” [friend] and “amis” [friends]). One question is when the spelling of such homophonous words is acquired; a closely related question is which errors are produced in spelling these homophonous words, as error patterns reflect the acquisition process. In the present study, we assessed Dutch children’s spelling outcomes and error patterns of homophonous targets whose final consonants are not spelled like they sound.

Spelling is relatively easy when phonemes can be converted to graphemes directly and consistently, but this is often not the case. Many language and spelling rules and conventions are involved in the correct spelling of phonologically inconsistent words. One important factor is morphology, the structure of words and parts of words, as specific graphemes reflect the morphological structure of the word. In French, for instance, the diminutive is spelled as “eau,” as in “éléphanteau” (little elephant) and is pronounced as /o:/. The morpheme spelling is different from other words ending in /o:/, as “o” (“piano”), “ot” (“escargot,” snail), or “aut” (“saut,” jump) (Pacton et al., Reference Pacton, Fayol and Perruchet2005). Similarly, the distinction between singular and plural “ami” and “amis” (friend(s)) is made through grapheme “s,” which is not pronounced (Gingras & Sénéchal, Reference Gingras and Sénéchal2019). Spelling inflected words correctly thus demands morphological knowledge as well as knowledge of “patterns involving the order and arrangement of letters, patterns that relate to spelling alone and not to pronunciation” (Treiman & Boland, Reference Treiman and Boland2017, p.255).

Homophones in Dutch present tense spelling

The morphological spelling pattern under investigation in this study is Dutch present tense spelling. A straightforward spelling rule is taught in primary school. Acquisition, however, is complicated by difficulties in phoneme-to-grapheme conversion and homophony. The spelling rule for present tense spelling is: First person present tense is the verb stem; (second and) third person singular present tense is stem+t.Footnote 1 For example, for the verb “tekenen” (to draw), the stem is “teken.” Present tense for first person singular is “ik teken” (I draw); present tense for the third person singular is “hij/zij tekent” (he/she draws). In this example, the distinction between singular and third person present tense is both audible (without a /t/ and with a /t/, respectively) and visible (stem-only and stem+t, respectively). Errors in which these two inflections are confused are unlikely to occur (e.g., *ik tekent I draws and *hij/zij teken he/she draw).

Present tense marking is the same for all verbs, including verbs with stems ending in a “d,” such as “vinden” (to find). First person present tense is the stem “vind” (“ik vind,” I find). This stem is written with a final “d” but pronounced with a /t/ (/vInt/) because of consonant-final devoicing in Dutch. The phoneme-to-grapheme association is thus complicated, as spellers have to know the association between the pronunciation (/t/) and the spelling of the final consonant (“d”) in the stem. They need the infinitive to know about the “d” (“vinden,” pronounced /vInd@n/). Third person singular spelling is stem+t, rendering “hij/zij vindt” (he/she finds). The grapheme –t in this third person singular is thus an orthographic morphosyntactic marker that has no phonological value. The pronunciation of third person singular “vindt” is the same as for first person “vind”; both are pronounced as /vInt/. Present tense spelling of -d-final verbs is thus likely to be challenging for children because of the non-transparent phoneme–grapheme association (/t/ to “d”) and because of the ensuing homophony: “vind” and “vindt” are spelled differently and reflect morphological differences, but sound exactly the same. It is, however, important to make the distinction between present tense verbs with -d or -dt, as this is needed for understanding the grammatical sentence context during reading (Brysbaert et al., Reference Brysbaert, Grondelaers and Ratinckx2000).

The majority of the Dutch present tense verbs take straightforward -t spelling. Less than 10% of all Dutch verbs include a choice between -d and -dt spelling (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002). However, as some homophone -d/-dt verbs are highly frequent (such as “vind” and “word”), there are many opportunities for errors to surface. This will impact on the ease of reading and understanding text (Brysbaert et al., Reference Brysbaert, Grondelaers and Ratinckx2000). Furthermore, such errors could impact on the reader’s perception of the writer, as spelling quality influences both the writer’s writing process and reader’s perception of the quality of the text (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Harris and Hebert2011). It has even been found that Twitterers that make fewer Dutch verb spelling errors have more followers (Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Chamalaun and Ernestus2018).

Homophone dominance in spelling Dutch present tense homophones

Homophone present tense verb spelling by adolescents and adults has received research attention and has been found to be difficult and error prone (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Sandra & van Abbeynen, Reference Sandra and van Abbeynen2009; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016). Specifically, the difficulty has been found to reside in implicit patterns that are present in spelling: The relative frequencies of the homophones contribute to the spelling outcomes. In written texts, present tense spelling “vind” (to find) occurs more frequently than “vindt,” whereas a verb such as “worden” (to become) shows the opposite pattern (“wordt” > “word”; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016). This relative frequency of orthographic patterns in present tense spellings has been found to affect present tense spelling of Dutch teenage and adult spellers (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Sandra & van Abbeynen, Reference Sandra and van Abbeynen2009; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016): Present tenses of verbs that occur more often as -d (d-dominant verbs, such as “vinden”) are more likely to be spelled with -d and also when they should take -dt. Thus, “hij/zij vindt” is likely to be spelled incorrectly as *hij/zij vind and “ik vind” is likely to be spelled correctly. In contrast, present tenses of verbs that occur more often as -dt (-dt dominant verbs such as “worden”) are more likely to be spelled with -dt and also when they should take -d (*“ik wordt”). Spelling errors based on homophone dominance imply that during spelling, adolescent and adult participants do not check the morphosyntax and the orthographic rule but instead rely on the implicit graphotactic frequency.

It is not yet known whether this homophone dominance is specific to adolescents and adults, or whether younger spellers at primary school already show this sensitivity. Children in the Netherlands are generally taught verb spelling in the higher grades of primary school (Grades 4–6), with present tense spelling instruction starting in Grade 4. Spelling instruction in the Netherlands is based on explicit and direct instruction, and the present tense spelling rule is no exception. Children are taught the stem+t rule for third person singular (“ik teken,” “hij/zij tekent” and “ik vind,” “hij/zij vindt”). Assessment of spelling of homophone present tense spelling in children at primary school can provide insight into the sources of information children use for this spelling pattern, establish whether they are similarly sensitive to homophone dominance as older, more experienced spellers (as reported in Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Sandra & van Abbeynen, Reference Sandra and van Abbeynen2009; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016), and whether the pattern changes after the instruction of the present tense spelling rule.

Challenges in spelling homophone present tenses for children at primary school age

There are different reasons why homophone present tense spelling might be challenging for younger spellers, that is, children at primary school age (Grades 1–6). Younger learners have been found to show difficulty in overruling phonology for orthography and/or morphology (e.g., de Bree et al., Reference de Bree, Geelhoed and van Den Boer2018; Gillis & Ravid, Reference Gillis and Ravid2006; Landerl & Reitsma, Reference Landerl and Reitsma2005). Such reliance on phoneme-to-grapheme associations would lead to -t spellings for all present tenses, including correct ones (“tekent” draws) as well as incorrect “t” spellings (*vint for both “vind” and “vindt” find). Spelling the -t is also endorsed by the orthographic frequency of word-final -t spelling in Dutch. The lexical database CELEX (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, Piepenbrock and Van Rijn1993) contains substantially more -t spellings (.88, 15,664 out of 17,680 present tense items) than -d (.045, 792/17,680) and -dt spellings (.075, 1,324/17,680). Thus, the phoneme-to-grapheme correspondence as well as the overall orthographic frequency would point children toward -t spellings.

Children might come to learn that -d endings are also possible, as the infinitive reflects the –d in both the spoken and written forms (“vinden” to find, “worden” to become) and as they have to overcome final devoicing across spelling (also in nouns such as “hond” /hOnt/ dog and adjectives such as rond /rOnt/ round; Gillis & Ravid, Reference Gillis and Ravid2006; Neijt & Schreuder, Reference Neijt and Schreuder2007). This would mean that -d spellings are made at some point, leading to consistent –d spellings (“ik vind/word”) and -d errors, such as *zij vind/*zij word. From Grade 4 onwards, children are taught the present tense spelling rule and are made aware of the inflection -(d)t. They have to overcome a potential -t or -d bias. Based on the fact that instruction takes place in this higher primary school grade (Grade 4) and on the fact that nonphonological graphemes are difficult to acquire (Gingras & Sénéchal, Reference Gingras and Sénéchal2018), correct -dt spelling might surface only in the higher primary school grades.

Sensitivity to homophone dominance might also only start to emerge in higher grades of primary school, and errors such as *“ik wordt” (I becomes) could start to surface due to the higher frequency of “wordt” compared to “word.” An alternative option could be that children show a -dt bias in higher grades, producing a -dt spelling for all homophone present tenses, regardless of homophone dominance. This would mean that they do not rely on the word-specific homophone ratio but on the higher present tense frequency of -dt spellings than -d spellings on the basis of the CELEX count (.075 vs .045, see above). Research has shown that spellers are sensitive to implicit orthography-related information from a young age onwards (e.g., de Bree et al., Reference de Bree, van der Ven and van der Maas2017; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Pollo, Treiman and Cardoso-Martins2013; Pacton et al., Reference Pacton, Perruchet, Fayol and Cleeremans2001) and that sensitivity to orthographic information increases with age (e.g., Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Pacton & Fayol, Reference Pacton and Fayol2000; van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019). This could imply that only older primary school children are sensitive to either a -dt bias or homophone frequency. In contrast, if the spelling rule that is taught in Grade 4 is applied correctly, then children in the higher primary school grades (Grades 4–6) should show better present tense spelling than the children in lower grades (Grades 2 and 3) and no influence of homophone dominance.

Homophone present tenses spelling and models of spelling development

Studying children’s Dutch present tense spelling, both the correct scores and the errors, can inform us about the acquisition process in light of different models of spelling development. Broadly speaking, a division can be made between models that assume that spelling acquisition is first primarily phonologically based before orthographic representations come into place and those that assume that nonphonological knowledge influences spelling from the onset of spelling acquisition onwards. In line with the former view, age/stage-based models (Ehri, Reference Ehri, Gough, Ehri and Treiman1992; Henderson & Templeton, Reference Henderson and Templeton1986; Nunes et al., Reference Nunes, Bryant and Bindman1997), for instance, assume that the pre-alphabetic and partial alphabetic phases are followed by the full alphabetic phase, in which all sounds are mapped to letters. Only after this phase do orthographic conventions come into play, as children begin to treat more frequently occurring letter sequences as chunks (Cardoso-Martins et al., Reference Cardoso-Martins, Corrêa, Lemos and Napoleão2006). Similarly, on the basis of dual-route models of spelling (e.g., Barry, Reference Barry, Brown and (Ellis)1994; Tainturier & Rapp, Reference Tainturier, Rapp and Rapp2001), it can be assumed that children start spelling acquisition by relying on the non-lexical route, in which sounds are mapped to letters (Alegria & Mousty, Reference Alegria and Mousty1996; Sprenger-Charolles et al., Reference Sprenger-Charolles, Siegel and Bonnet1998) and slowly develop and rely more on the lexical route, in which spellings are stored of words that have been previously encountered. This storage is influenced by lexical frequency, with high frequent words being stored faster than less frequent ones.

In contrast, the Integration of Multiple Patterns framework (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014) assumes that both information about specific words is stored, as well as different implicit (linguistic and orthographic) patterns that apply across words. Exposure to print can lead to the detection of (sublexical) patterns that are not part of the explicit literacy curriculum (e.g., Deacon, Leblanc & Sabourin, Reference Deacon, Leblanc and Sabourin2011; Kemp & Bryant, Reference Kemp and Bryant2003; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Kemp and Bryant2011), which subsequently influence (children’s) (sub-)lexical spelling performance (e.g., Cassar & Treiman, Reference Cassar and Treiman1997; de Bree et al., Reference de Bree, van der Ven and van der Maas2017; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Pollo, Treiman and Cardoso-Martins2013; Pacton et al., Reference Pacton, Perruchet, Fayol and Cleeremans2001; Treiman & Boland, Reference Treiman and Boland2017). Importantly, the pattern that is deduced is not always correct, as the findings on homophone dominance with adolescents and adults also show (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016). Incorrect pattern deduction has also been found in children’s spelling (e.g., van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019).

If children start with a phonological spelling approach and move to a lexical approach, then homophones are initially expected to be spelled with final -t (phoneme-to-grapheme association), whereas older children’s spellings would include -d and -dt spellings, as words with these patterns become known. Lexical frequency is assumed to play a role as spelling experience increases and spellings become available: lexical frequency will determine when -d’s will be spelled for -d final words, as well as when -dt’s will be spelled. Indeed, words that occur more frequently are spelled better than those that are less frequent (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Kemp and Bryant2011; Lété et al., Reference Lété, Peereman and Fayol2008; van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016; White et al., Reference White, Abrams and Zoller2013). With respect to the present tense homophones, it could be expected that the most frequent form of the pair will be spelled correctly more often. On the basis of these models, -d and -dt errors should not occur in non-homophone verbs, as these errors are not driven by phonology or by word frequency. In other words, -d and -dt errors should not occur in verbs that never take -d or -dt, such as *“hij/zij tekendt” instead of “hij/zij tekent” (he/she draws).

In contrast, if statistical frequencies play a role in early spelling, then effects of different sources of frequency can be anticipated (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014). These include lexical frequency, relative occurrence of -d and -dt within a homophone pair (difference between -d dominant and -dt dominant verbs), as well as general occurrence of -t, -d, and -dt in present tense verb spelling (-t being most frequent, -d least frequent). This could imply that children show effects of lexical frequency, of homophone dominance, as well as of occurrence of orthographic “d” and “dt” at the end of words in general. Importantly, the framework allows for the option that -d and -dt spelling errors could surface in contexts in which they do not appear, which contrasts with (st)age-based and dual-route models. Here, it could mean that -d/-dt errors could appear in third person singular present tense verbs that only take -t (*“tekendt” for “tekent” draws) and in past tense inflection (which never takes -dt, *vondt for “vond,” found).

Present study

In this study, we look into two unexplored questions that can inform us about spelling development. The first is whether Dutch Grades 2–5 children are sensitive to homophone dominance in present tense spelling. The second is whether this sensitivity is specific to verbs with stems ending in d, or whether they overgeneralize this sensitivity to other verb inflections. Children were presented with a dictation task. Homophone verbs were coded for homophone dominance (-d dominant, -dt dominant): For “word/wordt” (become), for instance, -dt is more frequently occurring than first person -d, making “worden” a -dt dominant verb. In contrast, for the verb “vind/vindt” (find), -d is the most frequently occurring representation and “vinden” is thus a -d dominant verb. If children are sensitive to homophone dominance, then -d dominant verbs should be spelled with -d more often, even if the target requires -dt (so, “hij vindt” he finds would be spelled incorrectly as *“hij vind”) and the opposite pattern should be present for -dt dominant verbs, with a reliance on -dt spelling even if the target requires -d (“ik word” I become would be spelled incorrectly as *“ik wordt”).

The expectation is that spelling in Grades 2–4 will progress from phonetic spelling (spelling -t for third person singular present tenses) to overruling final devoicing (spelling -d for the present tenses). In Grades 4 and 5, this might change to learning to spell graphemes without phonological value (also using -dt spelling), as the present tense spelling rule is taught and as exposure to these word forms increases. It is not known whether homophone dominance impacts on spelling in these grades. Homophone dominance has been found to affect spelling of Grade 6 children (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Sandra & Van Abbeynen, Reference Sandra and van Abbeynen2009), but sensitivity to this implicit cue might not be present in children in lower primary school grades. Next to homophone dominance, lexical frequency was also taken into account, as words that occur more frequently might be spelled better than those that are less frequent. Previous findings specifically focusing on present tense homophone spelling have shown that homophone dominance as well as lexical frequency affects adults’ spelling outcomes (Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016; White et al., Reference White, Abrams and Zoller2013).

With respect to the second question, it is not known whether children would produce -d(t) spelling errors in present tense verbs that do not take -dt inflections. All present tenses without stem-final “d” take only -t in third person singular (“hij/zij tekent,” he/she draws). Similarly, (irregular) past tenses never take -dt, as grapheme “t” is a present tense marker. Past tenses “werd” (became) and “vond” (found) can thus never be spelled as “werdt” and “vondt.” As far as we are aware, this prediction has not been tested. Therefore, both present tenses without stem-final -d and past tenses were included in the current study. Only if graphotactic information plays a role from an early stage onwards, could errors such as “tekend,” “tekendt,” or “vondt” occur. This would match assumptions from the Integration of Multiple Patterns framework (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014).

Method

Participants

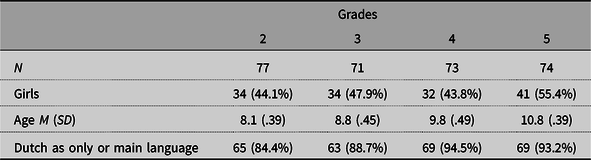

Information on number of participants, gender distribution, and language background is provided in Table 1. Children from Grades 2–5 participated in this study, 298 children (48% girls) in total, with a mean age of 9.3 years (SD = 1.2 years). The grades thus spanned almost the entire primary school range, as only Grades 1 and 6 children were not included. In the Dutch primary school literacy curriculum, spelling approaches are always direct and explicit. This is also true for present tense verb spelling, which is taught in Grade 4. The children attended one of four schools in the Randstad area, the urbanized part of the Netherlands. The majority of children spoke Dutch as their only language. Children who also spoke another language at home all received spelling instruction in Dutch at school.

Table 1. Participant information per grade

Note. Date of birth was not available for three children in Grade 4 and 1 child in Grade 5.

Instruments

Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of 16 present tense homophone targets and two sets of non-homophone verbs (two present tense non-homophones and two past tense verbs; see the online Appendix for all stimulus information).

Homophone present tense verbs

The homophone verbs refer to verbs with one pronunciation but two orthographic representations in the present tense (-d or -dt), as in first person singular “ik word” (I become) and third person singular “hij/zij wordt” (he/she becomes). The stimulus set contained eight homophone pairs (e.g., “word”-“wordt”), rendering 16 targets.

Verbs were labeled for homophone dominance using the homophone ratio: log 10(frequency -d form/frequency -dt form) (Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016). A positive ratio value indicates -d dominance and a negative value -dt dominance. A larger value indicates a more pronounced difference in frequency between -d and -dt. Lexical frequency values of the target words were obtained from SUBTLEX (Keuleers et al., Reference Keuleers, Brysbaert and New2010). Additionally, words were selected that had as low an age of acquisition (AoA) as possible, as words that children are likely to know the meaning of are spelled better than those that they do not know (e.g., de Bree et al., Reference de Bree, Geelhoed and van Den Boer2018). AoA values were obtained from Brysbaert et al. (Reference Brysbaert, Stevens, De Deyne, Voorspoels and Storms2014). Homophone dominance, ratio, lexical frequency, and AoA of the stimuli are presented in the online Appendix.

Non-homophone present tense verbs

Two non-homophone present tenses were included: “tekent” (draws) and “rent” (runs). Spelling these present tenses can be done phonetically as well as by following the simple present tense spelling rule; third person singulars are spelled with –t and pronounced with /t/ (“hij tekent,” “zij rent”). Spellings of these verbs can be used to evaluate whether children are able to inflect for present tense as well as whether “d” (*“tekend”) and “dt” (*tekendt) errors occur (as “d” and “dt” never occur in present tense spelling of these non-homophone verbs).

Past tense verbs

Two irregular past tense verbs (“vond” found and “werd” became) were included to assess whether children ever spell the past tense with -dt. Past tenses are never spelled with -dt, neither in regular and irregular past tense verb inflection. One target took third person singular (“zij werd”) and the other was first person singular (“ik vond”). Note that although neither form can take final -dt, as the -t marks present tense, this would be even more unlikely in the first person, as first person present tense never takes -t, whereas third person singular present tense does.

Task

Spelling was assessed through a dictation task. Each item started with the target verb, followed by the sentence and a repetition of the target. An example is: “brand. Ik brand mij aan het vuur. Schrijf op: brand … brand.”. [burn. I burn myself through the fire. Write down burn…burn]. Children had to spell the target verbs. The task was divided into two sessions; the homophone pairs were never presented in one session (e.g., no “brand” and “brandt” in one session) and the -d and -dt verbs were mixed over the two sessions such that both -d and -dt targets were presented in both sessions. Sentence length was kept to a minimum. The dictation task contained a total of 60 words from different spelling categories (verbs, long vowel spelling, loan words), and thus contained distractors to the pattern of present tense verb spelling. Reliability of the entire dictation was high (Cronbach’s alpha = .956) and for the homophone verbs only it was sufficient (Cronbach’s alpha = .797).

The proportion correct for the three verb types was calculated. For incorrect spellings, it was scored what type of error was made. A distinction was made between phonetic errors (spelling the final consonants as a “t,” as in *“brant” for “brand/brandt,” to burn), orthographic homophone errors (spelling -dt as -d, as in *“hij brand” or spelling -d as -dt, as in *“ik brandt”), and “other” orthographic errors in the coda (spelling, for instance -td [*“brantd”], -tt [*“brantt”], or -dd [*“brandd”]), all of which are illegal in word-final position in Dutch, or other parts of the target (e.g., *“branden” (to burn), or *“band” for “brand”).

Procedure

The design and procedure of this study were approved by the university’s ethical review board (2018-CDE-8741). The study was conducted based on approval by the school to participate and passive parental consent. Data were collected twice in the classroom as part of the regular literacy instruction. Each session contained 30 items and took approximately 45 min to administer. Three trained graduate students collected the data.

Data analysis

To assess whether Dutch children are sensitive to homophone dominance in the homophone present tense verbs, we applied linear mixed effects modeling using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2018). As the dependent variable accuracy was binomially distributed (1 = correct; 0 = incorrect), logistic regression was used. Separate models were fitted per grade (Grades 2–5). For each model, we included an intercept, as well as random intercepts for participants and for items, and a fixed effect of the control variable item frequency, followed by the independent variables of interest: form (0 = first person singular d, 1 = third person singular dt), homophone ratio (positive values =d-dominant, negative values = dt-dominant), and their interaction. This interaction is crucial for establishing the homophone dominance effect. If a dominance effect is present, then a higher homophone ratio of -dt would lead to more errors for targets with first person singular -d. Similarly, a higher homophone ratio of -d would lead to more errors for targets with third person singular -dt. To analyze spelling outcomes of the non-homophone present tense verbs and the irregular past tense verbs, one-way ANOVAs were conducted.

Results

Homophone verbs

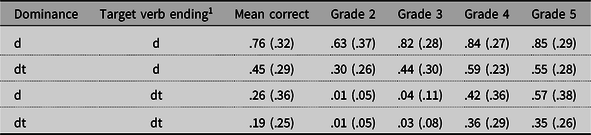

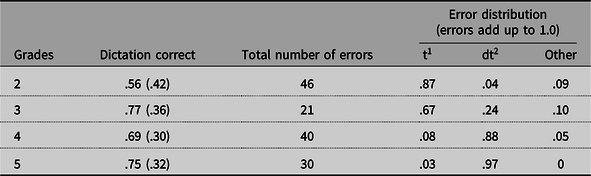

The dictation outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Dictation correct scores (and SD) of present tense homophone verbs divided by grade and homophone dominance

Note. 1d-targets refer to 1st person singular inflections; dt-targets to 3d person singular inflections.

The mean scores indicated that -dt targets (third person singular) are more difficult than -d targets (first person singular), and that -dt dominant verbs were more difficult than -d dominant verbs. These differences were tested with linear mixed effects models. For Grade 2, the dataset contained 1190 spellings (291 correct; 899 incorrect) for 16 items and from 77 participants. Forty-two observations were missing, because five children missed one of the sessions and one child skipped two items. For Grade 3, we analyzed 1109 spellings (371 correct; 738 incorrect) for 16 items and from 71 participants. Twenty-seven observations were missing because three children missed one session and one child skipped three items. For Grade 4, 1136 spellings (624 correct; 512 incorrect) were included for 16 items and from 73 participants. Thirty-two observations were missing because four children missed one of the sessions. Finally, for Grade 5 the analysis included 1144 spellings (669 correct; 475 incorrect) for 16 items and from 75 participants. Forty observations were missing, because five children missed one of the sessions.

The results of the statistical analyses are presented in Table 3. The main findings are highly consistent across grades. The absence of an interaction between homophone ratio and form is a null-result which we take to mean that children are not sensitive to homophone dominance. There is a significant main effect of form, indicating that first person singular (-d) targets were easier to spell correctly than third person singular (-dt) targets. There is also a main effect of homophone ratio, indicating that -d dominant verbs were easier to spell than -dt dominant verbs. Please note the continuous nature of this variable, indicating that the stronger the -d dominance, the higher the chance that the word is spelled correctly, and vice versa, the stronger the -dt dominance, the lower the chance that the word is spelled correctly. In addition, there is an effect of lexical frequency in all grades, except Grade 3, indicating that verbs that are encountered in print more often are more likely to be spelled correctly. In Grade 3, the effect of frequency pointed in the same direction, but was not significant (p = .076).

Table 3. Logistic regression coefficients for dictation in Grades 2, 3, 4, and 5

Note. * p < .05.

The effect of frequency might suggest that, despite the relatively low AoA, children might have had very little exposure to some of the verbs. An effect of homophone dominance is likely to emerge only when the verb is regularly encountered. We therefore added the interactions between frequency and homophone ratio and the three-way interaction between frequency, homophone ratio, and form to the models. None of the interactions reached significance in any of the grades, and the results for form, homophone ratio, and their interaction remained the same. There was only one small difference: In Grade 2, the effect of ratio no longer reached significance when the interaction between frequency and homophone ratio was included in the model. Therefore, the absence of homophone dominance does not seem related to the frequency of the verbs.

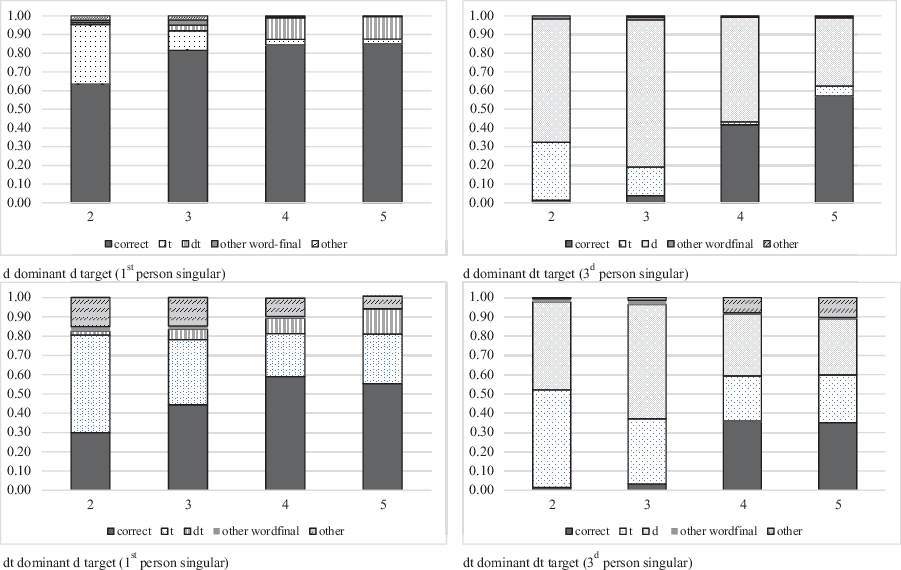

The distribution of correct and error scores for the homophone verbs is presented below in Figure 1. The errors made are predominantly word-final errors. Within the word-final errors, the majority are d/dt/t errors; graphotactically unexpected errors such as -td are rare. Regarding dominance, the top row shows the pattern for d-dominant verbs. There is a difference in the correct score between the d-targets and dt-targets. Across grades, the errors for d-targets change from predominantly -t errors (*vint) to correct scores and a small proportion of dt-errors (*vindt). The proportion of errors for -dt-targets remains high and changes from -t errors to -d errors. The bottom row shows the pattern for dt-dominant verbs. Whereas there is an increase in correct scores and a subsequent decrease in mainly t-errors for the d-targets across grades, the proportion correct scores for -dt-targets remain low and show both -t and -d errors. Notably, for dt-dominant targets, errors from the type “other” are also visible, whereas they are negligible for d-dominant targets.

Figure 1. Distribution of Outcomes for Verbs Divided by Homophone Dominance (d or dt) and Form across Grades.

Viewed from the perspective of form, the figures in the left-hand column show the first person singular (d-target) outcomes. The correct scores differ between targets that are d- (top) or dt-dominant (bottom), but the errors are predominantly t-errors in lower grades and include -dt errors in higher grades. For -dt dominant targets, there is a larger proportion of “other” errors. For third person singular targets (-dt), shown in the right-hand column, the correct scores remain low, for both d- and dt-dominant targets, but the error pattern is slightly different: for d-dominant targets, the errors change to predominantly d-errors in higher grades, whereas for -dt dominant targets, the errors include -t as well as -d errors.

Non-homophone present tense verbs

Findings on the verbs that never take -d or -dt (non-homophone present tenses) are presented in Table 4. The correct score, which contained considerable standard deviations, increased across grades but was not yet near ceiling in Grade 5. A one-way ANOVA with proportion correct and Grades (2, 3, 4, and 5) showed an effect of Grade F(3, 294) = 7.077, p < .001. The dictation outcomes of Grade 2 children contained significantly more errors than those of the other grades (ps < .01), but none of the other grades differed in correct scores.

Table 4. Proportion correct (and SD) on the two non-homophone present tense verbs

Note. Targets are “rent” (runs) and “tekent” (draws).

1 This “d” error refers to spelling the target incorrectly as *rend and/or *tekend.

2 This “dt” error refers to spelling the target incorrectly as *rendt and/or *“tekendt.”

In terms of the types of errors made, a change is visible across grades. The errors are predominantly -d errors (*rend, *tekend) in Grades 2 and 3, whereas in the higher two grades, -dt errors are also present (*rendt, *tekendt). Thus, whereas these non-homophone present tense verbs can easily be spelled correctly based on both morphology (stem + “t” for present tense) and phoneme–grapheme conversion (final consonant /t/ spelled like “t”), children’s spellings show orthographic -d and -dt errors.

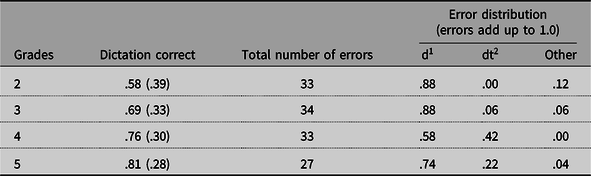

Non-homophone past tense verbs

Spellings of two irregular past tense verbs (that take -d, but never take -dt) are presented in Table 5. The scores, which show sizeable standard deviations, show a wave-like pattern, with an increase between Grades 2 and 3, a decrease between Grades 3 and 4, and an increase between Grades 4 and 5. In Grade 5, the correct score does not approach ceiling yet. A one-way ANOVA with proportion correct and Grades (2, 3, 4, and 5) rendered an effect of Grade F(3, 294) = .986, p = .002. The dictation outcomes of Grade 2 children contained significantly more errors than those of the Grades 3 and 5 children (ps < .01). Other differences between grades were not significant. These statistical test results thus largely support the wave-like pattern.

Table 5. Proportion correct (and SD) on the two irregular past tense verbs

Note. Targets are “vond” (found) and “werd” (became).

1 This “t” error refers to spelling the target incorrectly as *vont and/or *wert.

2 This “dt” error refers to spelling the target incorrectly as *vondt and/or *“werdt.”

The results show that the dictation errors change from the predominant phonological error (spelling the verb with “t” as the sound is /t/) in Grades 2 and 3 to the orthographic present tense inflection error (-dt). This error occurs despite past tense verbs never taking -(d)t. As the pattern is the same for “vond” and “werd,” it does not seem to be related to the fact that “vond” was a first person singular target (first person singular never takes -t in present tense) and “werd” a third person singular target (third person singular does take -t in present tense). The equal pattern between “vond” and “werd” also indicates that the pattern is not related to the homophone dominance of the present tense spellings: “vind” (-d dominant) and “wordt” (-dt dominant) are the dominant forms in present tense spelling. Thus, even though these are two highly frequent final -d past tense verbs, they are often incorrectly inflected with present tense marker -(d)t, already from Grade 3 onwards.

Discussion

To gain more understanding of spelling development, specifically of the influence of orthographic markers of morphological inflection, we looked into Dutch children’s spelling of present tense verbs that have a homophone form for first and third person singular. For the verb “worden” (to become), for instance, first person singular (“ik word,” I become) is pronounced exactly the same (/wOrt/) as third person singular (“hij/zij wordt,” he/she becomes), but because of morphological inflection, it is spelled differently. Previous research has shown that the persistent errors that adolescents and adults make in spelling these verbs are due to implicit patterns, specifically homophone dominance (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016). They thus spell verbs with the most frequently occurring inflection (e.g., “wordt”) regardless of whether the target form is first or third person singular, yielding incorrect spellings (e.g., *“ik word t,” I become). To establish whether children are also sensitive to this implicit cue or become sensitive to this pattern in primary school, we addressed two questions: 1) are Dutch Grades 2–5 children sensitive to homophone dominance in present tense spelling? and 2) do they overgeneralize this sensitivity to other verb inflections?

No evidence for sensitivity to homophone dominance in children

Children were asked to spell present tense verbs in first and third person singular forms, in which the target was either -d (“ik word,” I become) or -dt (“hij wordt,” he becomes), and in which the homophone dominance was either -d (“vind” > “vindt,” to find) or -dt (“wordt”>“word,” to become). There was no interaction between homophone dominance and form, nor did this effect emerge when interactions with word frequency were taken into account. We take these outcomes to indicate that children are not sensitive to homophone dominance in present tense spelling. We did find that -d dominant verbs were overall easier to spell than -dt dominant verbs, and first person singular (requiring -d) was easier to spell than third person singular inflection (requiring -dt), regardless of the verb dominance within a verb pair. These findings point toward a d-bias in children’s spelling of homophone verbs, similar to that of the Grade 6 teenagers in Frisson and Sandra’s study (Reference Frisson and Sandra2002). They found increased sensitivity to homophone dominance from Grade 6 upwards. We found no evidence of this sensitivity prior to Grade 6. Lexical frequency did affect spelling outcomes, with targets that are more frequent being spelled correctly more often. This matches previous findings on the role of frequency in spelling (Lété et al., Reference Lété, Peereman and Fayol2008; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Kemp and Bryant2011; van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016; White et al., Reference White, Abrams and Zoller2013).

We interpret this finding on the basis of the absence of an interaction between homophone dominance and form. It could be argued that this absence reflects a null-result, which neither confirms nor rejects the existence of homophone dominance. At the same time, sensitivity to homophone dominance in spelling homophone present tense verbs can only be attested by the specific interaction between form and ratio; the presence of a significant interaction indicates sensitivity to homophone dominance, and the absence of this significant interaction indicates that there is no sensitivity to homophone dominance (see also Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016; Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002). The errors made in spelling present tenses of homophone verbs further support our interpretation as we found different error types, not dominated by homophone dominance. We can rule out that statistical power prevents an interaction from surfacing, as other main effects in the anticipated direction were found. Importantly, the effects of form and homophone ratio point to a preference of -d over -t. Additionally, the findings relate to those of previous studies, in which the significant interaction is attested for adults and increasingly for adolescents, indicating increasing sensitivity to homophone dominance across ages (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002, Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016).

Differences in error pattern across grades

The errors that children made in spelling homophone present tense verbs generally showed a shift across grades from -t errors (*“wort”) to -d errors for -dt targets (*“hij word” for target “hij wordt”), as well as an increase of -dt errors for -d targets (*“ik wordt” for target “ik word”). These error patterns indicate that Grade 2 children spell verbs like they sound, as phoneme /t/ is converted to the letter “t.” This phonetic approach is supported by orthographic frequency, as a d/dt distinction for a /t/ sound exists in less than 10% of the Dutch verbs (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002) and as our CELEX count showed that there are many more spellings of -t present tenses than -d or -dt ones (see ‘Homophones in Dutch present tense spelling’ above). Across the grades, the t-errors change to spelling errors that indicate more orthographic and morphological knowledge, as -d’s (and -dt’s) appear.

The error pattern was not the same for all verbs, though: the -dt dominant verbs (both -d and -dt targets) contained more “other” errors than the -d-dominant verbs and their spellings persistently included a higher proportion of -t, next to -d errors. Although we cannot assess with certainty what the cause is of this higher proportion of -t errors, it seems unlikely that it reflects a phonetic error, as -t errors decrease across grades overall. It is also unlikely that children do not know the -d and -dt spellings, as they use these spellings both increasingly correctly across grades and increasingly as errors for the other targets. Possibly, the -t-errors reflect a performance error; children apply the spelling rule and are thus aware of the need to add -t. The complexity of the rule leads to them omitting the “d” in the -dt. In other words, the spelling rule might be demanding, leading to performance errors. Such an interpretation could also account for the higher proportion of “other” errors attested. In this speculative line of reasoning, there might already be some effect of -dt dominance, as these -t and “other” errors occur for -dt dominant verbs regardless of the target (first person -d and third person -dt).

Generalization errors in non-homophone present tense and irregular past tense verbs

The findings that children in primary school are not sensitive to homophone dominance and that -dt targets are difficult to align with those on the non-homophone present tense and irregular past tense verbs, although those latter findings are in itself rather surprising. Results show that even in Grades 4 and 5, after instruction of the present tense spelling rule, children make a substantial percentage of errors in straightforward present tense verb spelling (20–25% errors). Present tense verbs without stem-final -d always take -t only in third person singular (“hij/zij tekent,” he/she draws) and cannot take -d or -dt. Nevertheless, Grades 4 and 5 children’s errors show predominantly final -d spelling in dictation (*“hij/zij tekend”) as well as -dt errors (*“hij/zij tekendt”). These errors are not likely on the basis of a phonetic spelling strategy and on the basis of the predominant -t in present tense spellings (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002), but suggest that graphotactic information plays a role from an early age onwards (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014).

A similarly remarkable pattern is attested in the spelling outcomes of the irregular past tense verbs: not only are many errors still made in Grades 4 and 5 (25–40%), but in these higher grades, the errors are overwhelmingly -dt errors. Such errors are phonologically unlikely and morphologically impossible (final -t and -dt mark present tense, not past tense) and should therefore never occur in past tense verbs in written texts. Nevertheless, children clearly produce them. These errors in the higher grades might be caused by instruction of the present tense spelling rule: the correct score on these past tenses shows a wave-like shape, with a decrease in correct score between Grades 3 and 4. This decrease coincides with a strong increase of -dt errors. The Grade 4 children might thus apply the present tense rule to an incorrect verb tense, while they, paradoxically, do not seem to apply the present tense spelling rule for present tense verbs successfully.

The present tense spelling rule is thus complex for the children, in line with the interpretation by Frisson and Sandra (Reference Frisson and Sandra2002) that “[s]ince the spelling rules involve determining the syntactic relationship between items and since in most cases phonology will give you the right answer, these descriptively simple rules might in practice be quite abstract for young spellers” (p.551). Children might thus understand that there are rules concerning verb inflection, but apply them in the incorrect contexts. Although it could be understood why this rule might be applied incorrectly in phonologically and morphologically more complex verbs, such as the (irregular) past tenses, it is not clear why this would be the case for non-homophone phonologically and morphologically straightforward present tenses, especially when the rule is not applied (correctly) in the homophone verbs. On the basis of our data, we cannot disentangle whether children relied on the present tense spelling rule for spelling the past tense and the non-homophone present tenses and/or whether they relied on different sources of information, such as general knowledge of existence of -d/-dt spellings.

Implicit cues and models of spelling development

It could be the case that the present tense -d/-dt and the past tense -dt errors are related to increased print exposure. As children read more, they encounter more words that contain final -d and -dt. These frequencies can thus be incorporated in children’s spelling. Note that graphotactic errors such as -td were very rare, indicating that children used sequences they encountered during reading and spelling. The assumption that print exposure influences the spelling of -d/-dt in incorrect environments relates to other studies. For instance, in a study into Dutch regular past tense spelling, frequency of word-final graphemes was found to be a source of children’s spelling errors (de Bree et al., Reference de Bree, van der Ven and van der Maas2017) and this error occurred more often for older readers and better readers (van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019). Furthermore, Pacton and colleagues (Reference Pacton, Borchardt, Treiman, Lété and Fayol2014) report a series of experiments on incidental learning of spelling with adults. Their findings indicate that word-specific knowledge is used in reconstructing spellings that the participants were exposed to, but that knowledge about the general graphotactic patterns of their writing system also accounted for the incidental learning outcomes. In our study, children seemed to use this general orthographic pattern of -dt in incorrect phonological and morphological environments. It is puzzling that this pattern does not surface clearly in homophone present tense spelling, but only in the other verb inflections assessed.

Our finding that the homophone graphemes are already used incorrectly in other environments partly agrees with a study by Nunes and colleagues (Reference Nunes, Bryant and Bindman1997), who found that there is an increase in children’s morphological knowledge in spelling across ages. Children were found to use morphological spelling patterns such as past tense from an early age (6 years) onwards, but to apply them incorrectly, both within past tense verbs (*keped for kept) and words that were not verbs (*sofed for soft). Across age, the quality of the morphological spellings improved. In contrast to the study by Nunes et al. (Reference Nunes, Bryant and Bindman1997), we are anticipating more errors to occur as children get older instead of less (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Verhaert, Reference Verhaert2016), but only in the homophone present tense verb environments. At the same time, we are not certain that the -d and -dt errors in incorrect morphological environments will disappear.

In all, the results of the current study show that there is a complex interplay between phonology and orthography in morpheme spelling that is different for children than the patterns previously reported for adolescents and adults. Our findings can partly be accommodated in both the age/stage-based (Ehri, Reference Ehri, Gough, Ehri and Treiman1992; Henderson & Templeton, Reference Henderson and Templeton1986) and dual-route models (Barry, Reference Barry, Brown and (Ellis)1994; Tainturier & Rapp, Reference Tainturier, Rapp and Rapp2001), as there are effects of lexical frequency, and as there seems to be a change from a phonetic to a more orthographic-based spelling strategy. At the same time, these models cannot easily accommodate the findings that there is no effect of homophone dominance yet in our Grade 5 children, especially not for the highly frequent words, but that -d and -dt errors do surface in the wrong place (non-homophone verbs).

The Integration of Multiple Patterns framework (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014) is able to account for these findings, as it assumes that linguistic and orthographic patterns influence spelling acquisition. These patterns include word-specific and general graphotactic patterns. Although this framework has a better fit to the data, it is a challenge to accommodate the finding that the -d and -dt errors surface in the wrong place and thus morphologically mark the wrong time, but at the same time do not surface in the homophone present tense environment (yet). The framework is not specific as to when the different sources would become available and would be used, only that it will become available during development, with more print exposure, statistical support for the pattern and convergence of the pattern with other patterns and with the learner’s linguistic knowledge (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014, p.272). Thus, children are sensitive to some graphotactic patterns from an early age onwards, but become increasingly sensitive with more exposure and experience, as has been reported previously (Frisson & Sandra, Reference Frisson and Sandra2002; Pacton & Fayol, Reference Pacton and Fayol2000; van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019). The present findings indicate that accounts of spelling development need to take different statistical cues into account as well as different spelling environments. For instance, it should be assessed whether similar errors also appear in noun spelling, with nouns never taking -dt (e.g., “hond” dog being spelled as *hondt). Additionally, such a study should include nouns that resemble their verbs, such as “bloed” blood, which can also occur as verb “ik bloed” (I bleed) and “hij/zij bloedt” (he/she bleeds) (Sandra & van Abbeynen, Reference Sandra and van Abbeynen2009).

Practical implications

The findings of this study have implications for the literacy curriculum. For instance, they reiterate the importance of teachers’ possessing both didactic knowledge and linguistic and orthographic knowledge of spelling, such as understanding the different spelling errors children can make (e.g., Carreker et al., Reference Carreker, Joshi and Boulware-Gooden2010; Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014). This is needed to distinguish straightforward (phonetic) present tense errors (*“ik vint”) from more complicated ones, such as *“ik vindt.” This latter error can reflect a -dt preference, homophone dominance, or incorrect application of the present tense spelling rule. Depending on the cause of the error, feedback and instruction need to be provided. Such spelling knowledge also allows a teacher to understand why an error such as *“ik vondt” (“ik vond” I found) could occur.

The fact that homophone dominance does not play a role yet in primary school children’s present tense spelling is hopeful, as “warnings” against this process can be made through spelling education. By discussing errors such as *“ik vindt” and *“hij/zij vind,” children in the higher primary school grades might become aware of the traps that lie ahead. This means that knowledge and application of morphosyntactic structure need to be stimulated. Knowledge of first and third person singular needs to be applied during spelling: children need to know that I stem+t spellings can never occur, not as *“ik rent” (I runs) nor as *“ik vindt” (I finds), but that third person singular should take stem+t (“hij/zij vindt” similar to “hij/zij rent”). Furthermore, for more advanced spellers, the existence of homophone spellings and related influence of graphotactic patterns (-d/-dt frequencies as well as homophone dominance) can be introduced.

The children’s -d and -dt errors in a non-homophone present tense context (“rend” or “rendt” for “rent” (runs)) and -dt errors in a non-homophone past tense context (“vondt” for “vond”(found)) also indicate that attention needs to be devoted to graphotactic errors in incorrect environments. This too requires children to receive instruction on morphosyntactic structure and graphotactic patterns. Specifically, children need to learn that spelling inflections is based on morphosyntax and that this is decisive for final -t/-d/-dt. For all verb spellings, the information can be provided both in formal, systematic, and explicit instruction and in informal and implicit discussions, when discussing reading material or writing assignments, for instance (e.g., Henderson & Templeton, Reference Henderson and Templeton1986; Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014).

Importantly, on the basis of our findings it could also be an option to teach present and past tense spelling simultaneously rather than sequentially. Generally, sequential teaching takes place (first present tense, then past tense), but this sequential approach might actually confuse children in using -dt (only occurring in present tense) and -d (occurring in present and past tense) spellings. Instead, students might benefit from the use of minimal pairs (Treiman & Kessler, Reference Treiman and Kessler2014). Contrasting examples in which the rule holds (i.e., vind/vindt, find), with similar examples in which the rule does not hold (i.e., vond, found) has been suggested to help students correctly apply the rule, as well as diminish incorrect generalizations. Previous work in Dutch also indicated that such a simultaneous approach might facilitate the acquisition of a different spelling pattern, that is, vowel length spelling (Drijver et al., Reference Drijver, van den Boer and de Bree2020).

Limitations

The present study is qualified by several limitations. The first concerns the item set. The targets included only a limited number of homophone verbs, many of which had a relatively low frequency (and higher ages of acquisition). This could affect evaluation of the potential homophone dominance effect. However, it was clear that there were no effects of homophone dominance and also not in interaction with frequency. The targets also included only a very limited set of non-homophone verbs: two -t present tense and two irregular past tense verbs. Although the number of participants was substantial and the pattern of these four verbs does point toward the use of incorrect -d and -dt by children in higher grades, spelling data of more non-homophone verbs is needed to confirm this pattern.

A related limitation is that frequency measure used might not be the most adequate measure for lexical frequency for children. Even though the SUBTLEX values (Keuleers et al., Reference Keuleers, Brysbaert and New2010) correlated significantly and strongly with the CELEX values (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, Piepenbrock and Van Rijn1993), these do not necessarily reflect the frequencies with which children are exposed to the verb spellings. Furthermore, recent studies have raised other issues related to frequency (see Brysbaert et al., Reference Brysbaert, Mandera and Keuleers2018; Castles et al., Reference Castles, Rastle and Nation2018), such as whether mere frequency is suitable or whether the different settings in which a word is encountered should also be incorporated, whether there are individual differences in frequency effects, and whether word prevalence might be a better measure than word frequency. The development in the field might thus further shape our understanding of the way spelling is affected by frequency. Furthermore, we would like to add that such a measure of frequency should also include the frequency with which children are exposed to incorrect spellings. These relate not only to their own errors but also to spelling errors in the texts they read.

A third limitation is the fact that only item factors were taken into account and that no child-based factors of reading and language abilities (vocabulary, morphology, phonological awareness) were included. Previous research has shown that inclusion of item- and child-based factors provides more insight in the mechanisms involved in spelling and allows more understanding of the differences between poor, typical, and advanced spellers (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Petscher and Park2016; van der Ven & de Bree, Reference Van der Ven and de Bree2019). Although this is a necessary avenue for further research, our study was specifically limited to assessing whether homophone dominance occurred at all in primary school children’s spelling.

Conclusions

In sum, we take our results to show that primary school children are not yet sensitive to homophone dominance in present tense verb spelling. Although this is good news, as literacy instruction could prevent the dominance effect to surface in later grades, the findings also showed that errors related to homophone inflection occur, in the wrong place, marking the wrong time. These findings point toward the important role that orthography and specific graphotactic patterns play in literacy development and speak to the plea for devoting attention to graphotactic patterns in models and teaching of spelling (e.g., Treiman & Boland, Reference Treiman and Boland2017). They indicate that models of spelling development need to include lexical, phonological, grammatical, as well as orthographic cues.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716421000254

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the children and teachers for their participation and the students involved in data collection, Sylvia Drijver, Samira van Emst, and Tessa van der Mark. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest

Credit statement

Elise de Bree: conceptualization, project administration, writing original draft, writing review and editing.

Madelon van den Boer: formal analysis, project administration, writing original draft, writing review and editing.