In all of the prehistoric and paleontological disciplines … it is recognized that, in the absence of a Wellsian time-machine, observed behavior must be foregone in favor of inferred behavior and experiment in favor of logic.Footnote 1

There is a surprising amount of literature on the subject of language origins for a topic said to have been eradicated by the Linguistic Society of Paris in 1866.Footnote 2 Much of this work, Charles Darwin's The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex notably included, has been undertaken outside mainstream linguistics and through broad interdisciplinary collaborations in fields devoted to human prehistory.Footnote 3 Fittingly, it has given rise to several innovative coinages – glossogony, palaeolinguistics and glossogenetics, for example. This article takes stock of research on this frontier roughly a hundred years after Charles Darwin addressed it in The Descent, with particular emphasis on the work of Mary LeCron Foster (1914–2001).

Drawing on primatology, anthropology, semiotics, cognitive science and comparative linguistics, to name just a few fields, research on the evolution of language has been defined by a number of characteristic lines of investigation. Some have focused on the question what is language – how does the human verbal system relate to other forms of communication? Thinking about such comparisons chronologically, others have queried, did our ability to speak appear gradually or overnight? Furthermore, and regardless of tempo, research programmes have been structured around the question of monogenesis – did language arise once or many times, and how might one know? Taking a different tack, evolutionary linguists have asked, how and to what extent is language related to thought? Are these faculties localized in the body, and if so, would it make sense to talk about a ‘language organ’? Working at the interface between disciplines, they have also interrogated causes underlying the origination of human language – should research primarily look to cultural or biological mechanisms? Finally, researchers have puzzled over ways in which the ‘evolution of language’ might relate to ‘language evolution’. In other words, questions have been raised whether uniformitarian expectations are appropriate here or not.Footnote 4

Remarkably, Darwin anticipated twentieth-century debate on all of these topics in just a few pages of The Descent.Footnote 5 His chief commitment in doing so was to highlight continuities across the animal–human divide, as historians Stephen Alter and Gregory Radick have argued.Footnote 6 For this reason, he emphasized correspondences between verbal and non-verbal systems of communication, looking for examples that might fill that manifest gap. Though willing to admit that the ‘habitual use of articulate language is … peculiar to man’, Darwin maintained key commonalities ‘with the lower animals’, among them ‘inarticulate cries … gestures and the movements of the muscles of the face’.Footnote 7 Gradualism was, unsurprisingly, a cornerstone of this continuity thesis, meaning that language was not ‘deliberately invented’ but rather ‘slowly and unconsciously developed by many steps’.Footnote 8 Crucially, however, Darwin demurred on the question of linguistic monogenesis, as he was elsewhere at pains to demonstrate the common origins of the ‘races of man’ while at the same time striving to decouple patterns of linguistic and racial descent.Footnote 9 Beyond such analogical considerations, he expressed further commitments to the co-evolution of language and thought, given the prior realization of a capacity for abstraction; partially anticipated Chomskian theory with his ontogenic reflections on child language acquisition; and even set the stage for memetic thinking about the differential survival of certain words.Footnote 10

Given that so many areas of contemporary research were introduced by a single chapter of The Descent, it is remarkable that so few authors writing on the topic of language origins have engaged the text substantively (or even directly) in the years since its publication.Footnote 11 Insofar as diachronic linguistics has seen itself in a ‘Darwinian’ light, this has tended to involve a general conceptual appeal to materialist, genealogical, uniformitarian and gradualist models found in The Origin of Species.Footnote 12 How might we interpret this neglect? Linguist Salikoko Mufwene suggests that subsequent research has simply proven a number of Darwin's points about language wrong – on the comparative anatomy of primate vocal tracts, for instance.Footnote 13 Or perhaps this avoidance can be explained in terms of The Descent's association with issues of race, sex and other controversial legacies in the human sciences during the twentieth century. Another explanation might take aim at the limits of interdisciplinary reading practices – their tendency to traffic in sparks and styles rather than substance.

Yet it is precisely the uniformitarian substance of what Darwin says about language in The Descent that mainstream linguists have found so difficult to accept. For instance, the second edition points to connections between linguistics and biology as follows: ‘The formation of different languages and of distinct species, and the proofs that both have been developed through a gradual process, are curiously parallel’.Footnote 14 The analogy here is between historical languages and species, suggesting similar phylogenetic patterns, something that has been generally embraced by comparative-historical linguists since the nineteenth century.Footnote 15 From these words, Darwin pivots swiftly to the topic of prehistorical language: ‘we can trace the formation of many words further back than that of species, for we can perceive how they actually arose from the imitation of various sounds’. Darwin does not provide examples for this assertion, and the extension has been rejected by most linguists who differentiate sharply between (historical) ‘language evolution’ and the (prehistorical) ‘evolution of language’.Footnote 16

Efforts to push back beyond the ten-thousand-year curtain have been denounced as speculative and relegated to the disciplinary fringe. As science writer Nicholas Wade cast the issue at the dawn of the new millennium, ‘Because of language's central role in human nature and sociality, its evolutionary origins have long been of interest to almost everyone, with the curious exception of linguists’.Footnote 17 Wade's assessment is confirmed, for example, by surveys of curricula defining the summer Institutes of the Linguistic Society of America during the last quarter of the twentieth century.Footnote 18 Where research has been conducted by linguists on the origins of language, it has been a notable departure from the discipline's bread and butter.Footnote 19

To survey the interests of ‘almost everyone’ would be well beyond the scope of this article. Instead, I cut a narrow path through the debates about language origins, focusing on the fraught relationship between historical and prehistorical ways of thinking about linguistic descent roughly one hundred years after Darwin was writing. According to one representative commentary, ‘speculations about the earliest stages of the development of human language’ were enjoying new and ‘firmer empirical … underpinning in animal behavior studies, semiotics, and linguistics’ at that time.Footnote 20 These threads come together in the linguistic anthropology of Mickie Foster, as she was known. A deeply interdisciplinary thinker, who nevertheless had formal training in linguistics, Foster developed an idiosyncratic account of ‘vocal iconicity’, which I read against more mainstream investments in Charles Hockett's ‘design features of language’ and Chomskian universals. These comparisons allow me to highlight the disciplinary, ideological and professional stakes of research on language evolution during the later twentieth century.

From anthropology to linguistics

Mickie Foster grew up in an adventurous and writerly family, seeding lifelong interests in anthropological diversity and linguistic expression. As an undergraduate, she attended Northwestern University, where she discovered anthropology under the tutelage of Melville Herskovits, earning her BA alongside her future husband, George Foster, in 1936. Herskovits was an important mentor for the couple, inviting them to private parties where they conversed with Bronisław Malinowski and Zora Neale Hurston, among other leaders in the field. Upon her graduation, Foster went on to graduate studies under Ruth Benedict at Columbia, where she also met Franz Boas. Though she only spent one year at Columbia before leaving to start her own family, Foster received the ‘imprint of Boas’ in her time there. According to her student and collaborator, Stanley Brandes, this was particularly evident in her ‘abiding interest in origins’ and her deep commitment to the four-fields approach.Footnote 21

After their reunion, Mickie and George travelled to Mexico, where they carried out extensive fieldwork in a Sierra Popoluca community, taking down notes that led to the first published grammar of that language.Footnote 22 As she later recalled, this linguistic turn in her career was largely ‘accidental’ and clearly opportunistic. Fieldwork that first year was tough going. ‘In order to get anybody to sit down and talk to us’, she recalled, ‘We decided to tell them we were interested in the language and see if we could pay somebody to come and talk to us about the language. We thought that would be a legitimate way to get started’.Footnote 23 At that time in the mid-1940s, the couple had minimal training in linguistics. Mickie had taken one course – ‘Language’ – with the ethnomusicologist George Herzog at Columbia, but she otherwise drew only upon her knowledge of French and German in elicitation sessions with native speaker Leandro Perez. And her husband didn't fare much better: ‘George had had some course that had to do with phonetics at Cal from [Alfred] Kroeber’, but nothing more.Footnote 24 Mickie was the scribe.

This was the first time the Sierra Popoluca language had been written down in any detail, and the Fosters’ preferred orthography was chiefly homemade.Footnote 25 Phonemic theory was not yet a routine point of graduate instruction when they left for Mexico, though they returned to find it all but required for the practice of linguistic fieldwork.Footnote 26 Fortunately, Mickie, who was travelling primarily as George's assistant at the time, intuited her own phonemic system. Her fieldwork experiences gave her a distinct advantage when she returned to graduate study in linguistics at Berkeley some twenty years later. She completed her PhD under Mary Haas with a dissertation on the Tarascan language in 1965.

Linguistics had become transformational in the interim, moving away from its anthropological roots in North American academe. Echoing retrospectives given by other members of the first generation of American linguists, Foster told interviewer Suzanne Riess in 2000,

[Chomsky] changed the system so drastically, so that all the things that had been pervasive in the anthropological linguistic tradition were being thrown out of the window; all these students had gone off into the field and were doing their dissertations on Amerindian languages and they didn't know how to write their grammars now, because the field was in complete upheaval … the way linguistics had worked before Chomsky started out with the phonology … The grammars were built up always from the phonemics into the morphology, which is the grammatical structure with affixes and went on whatever a particular language is made up of. So it went from short stretches, to longer stretches, and finally then into words, the way words were put together and then into the way that sentences were put together. But Chomsky started with sentences, clauses, and worked the structure down from the top to the bottom, so it was a complete reversal of the way that linguists had been looking at language, starting with Boas.Footnote 27

This ‘revolution’ – institutional and political as much as it was conceptual – bore direct consequences for the study of language origins. The emergence of the transformational-generative school focused the attention of evolutionary thinkers on a new definition of language, a catastrophist picture of its emergence grounded in the study of childhood language acquisition, a highly rationalist appreciation of hierarchical language structures, and even put forward the notion of a distinct language organ in the brain. As psychiatrist Stevan Harnad surveyed the new landscape surrounding research on the evolution of language in 1975, he saw new opportunities to revive the Darwinian project:

Virtually all aspects of our relevant knowledge have changed radically since the nineteenth century. Our concept of the nature of language is totally altered and has become both more profound and more complex. The revolution in linguistics due to Noam Chomsky has provided a very different idea of what the nature of the ‘target’ for the evolutionary process might actually be. We are told that there are features of language that cannot be learned from experience, and we hope it will be possible to consider … what other kinds of origins such features may have had …Footnote 28

These ideas were in the air when Foster returned to graduate school in her mid-forties. She had dropped out of Columbia nearly twenty years before to start a family with George, and she found it difficult to return during the itinerant years of his early professional career. In her words,

George and I had started out together, and when we were at Northwestern, we were about equally good students, and both equally interested in the subject matter. The reason he got ahead of me was because we began having kids pretty soon, and that took a good deal of my time and energy.Footnote 29

By the time she felt ready to resume formal studies, Foster told members of the Society of Women Geographers in 1994, certain doors had closed. ‘I had been hoping to go back to graduate school all the time that we were making all these moves [for George's career], but the moves kept cutting into it, and I had other fish to fry and couldn't seem to get established’.Footnote 30 When the stars eventually did align at the University of California, Berkeley, Foster ‘had to think what I was going to do’, as her husband had by that time become chair of the very anthropology department in which she would have preferred to study. So she pursued linguistics instead. ‘I thought, well, it will be easier … since I was an older student and the wife of a professor … You feel as if you have to work twice as hard as everybody else in order to prove that you're really somebody who should be doing this’.Footnote 31 She expressed gratitude about the separation of linguistics from anthropology in the 1950s, saying,

if linguistics had not been separated from anthropology at Cal, I wouldn't have had the option of getting my degree in linguistics. It was useful for me, at that time, and I was glad I did linguistics for many reasons. When I did it when I did, for good reasons too, the ‘when’ part had to do with the fact that the field changes so fast. If I had gotten my degree much earlier and then had a hiatus, my style of linguistics would have been completely out of date, so I would have had to learn it all over again.Footnote 32

Though she would go on to teach at Cal State Hayward and the University of San Francisco, her primary intellectual community seems to have remained at Berkeley.Footnote 33 She participated in department events and helped her husband's advisees, and the anthropology library on campus even bears her name.Footnote 34 The one regret she consistently expressed about her career was that she never had the opportunity to train graduate students of her own.Footnote 35 The scope of her linguistic reconstruction project called for an army of advanced researchers, which she was never able to assemble as an informal member of the university community.Footnote 36

The rhythm of Foster's career provides an interesting counterpoint to standard accounts of the development and institutionalization of American linguistics during the twentieth century. Whereas established narratives have emphasized such factors as the linguistic institutes of the 1930s and 1940s and the spur provided by wartime language work, Foster's family commitments set her down a different path.Footnote 37 While she participated in the fieldwork imperative that characterized anthropological linguistics after Boas, marriage and motherhood repeatedly put Foster a decade or two out of step with major theoretical turns in linguistics – phonemics and transformational grammar most notably. This gave her enormous freedom to define a unique research programme – ‘her own brand of historical linguistics and anthropological symbolism’ – an approach that was critical of the formalist tendency to obscure meaning.Footnote 38 Her timing also led to professional marginalization.

Animals, arbitrariness and the science of language

Scientists turned to questions of human nature – its uniqueness and defining characteristics – with urgent interest in the aftermath of the Second World War.Footnote 39 The Fosters were criss-crossing North America in these early years of UNESCO's ‘universal man’ and his attendant sciences. Mickie became convinced of a sympathetic linguistic monogenism during the 1960s. She came to this position through the comparative analysis of a progressively inclusive data set of world languages, starting with just two from Mexico.Footnote 40 This kind of comparative linguistic work merged with studies of animal communication and semiotic theory, contributing to a surging interest in language origins roughly a century after Darwin published The Descent of Man.

Reflecting on the convergence of these streams for readers of Current Anthropology in 1976, Georges Mounin observed, ‘In the last ten years, entirely new experiments have been undertaken’, providing evolutionary linguists with the evidence they had been missing at long last.Footnote 41 Mounin's appraisal of this literature highlights a matrix of linguistic alternatives and ‘semiological’ models that informed the reception of evolutionary linguistic study during the 1960s and 1970s.

In the first instance, there were claims about the threshold criteria for ‘language’. Following Noam Chomsky, syntax was thought to be a necessary and universal feature of human language, which retained a special status.Footnote 42 This position, however, proved vulnerable to the criticism that Chomsky and others had confused a description of (human) language for the definition of language as such. Motivated by a desire to escape such circularity, Charles Hockett proposed an account of language that focused on a list of constitutive features instead of universals – a list that grew steadily over the course of the 1960s. For Hockett, the design feature of arbitrariness – the independent variation of form and meaning – was the relevant boundary, not some putative universal of human speech.Footnote 43

Furthermore, Mounin found that some of the primate studies justified a ‘train of thought extending from Saussure to Whorf’ by which language was figured as the externalization of experience and concepts. ‘[T]o verify that there is no way to acquire a meaning other than differentially’, he wrote, provides ‘a good experimental demonstration in animal psychology of Saussurian semantics’. Here, the research conducted by Ann and David Premack with chimpanzees during the 1960s was held out as a prime example.Footnote 44

Several commentators on the paper picked up on this semiotic assertion. Together, they show that an ability to abstract away from human language was thought to be the key to prehistorical linguistics. As Jean Umiker-Sebeok put it, the challenge was to identify a ‘semiotic theory … of sufficient scope as naturally to encompass, on the one hand, animal sign behavior and, on the other, the more highly developed signs of man, such as propositions and arguments’.Footnote 45 Only in this way would the human sciences ‘account for the coexistence within man of what is still animal and what is no longer so’.Footnote 46 Mickie Foster's work targeted precisely this issue, and Sherwood Washburn was eager to include it in his 1978 book with Elizabeth McCown on Human Evolution: Biosocial Perspectives – a complement to his brand of physical anthropology.Footnote 47

Of these models, Hockett's list of design features was most legible for those working within the historicist and empirical branches of linguistics. He was a self-proclaimed ‘scientist’, by which he meant a student of indigenous American languages, possessed of the conviction that ‘linguistics without anthropology is sterile; anthropology without linguistics is blind’. Following a common career path for his generation, he studied with Edward Sapir, became a language specialist with the US military during the 1940s, and was among the first generation of American linguists to institutionalize the discipline in the postwar era.Footnote 48 Just two years after securing his position at Cornell University, he penned the first of a series of publications on the relationship between linguistics and biology.Footnote 49

He expanded on this preliminary paper in his 1958 textbook A Course in Modern Linguistics, taking on questions of linguistic prehistory (Chapter 55) alongside an exploration of ‘Man's place in nature’ (Chapter 64). Hockett's treatment of ‘prehistory’ in this text accords with the most straightforward sense of the word – a reconstruction in the absence of written records. By way of introduction to the topic, he wrote,

Our earliest written records, in any part of the world, date back only a few millennia; the best that linguistic prehistory can do in any detail is to extend this horizon back a few millennia further. But there are good reasons for the belief that our ancestors have possessed language for much longer, perhaps millions of years. The deepest attainable detailed temporal horizon thus represents a mere scratch on the surface. Any deductions that can currently be made about the evolution of language, in contrast with the history of specific languages or language families, require very different techniques, involving the study of the communicative behavior of our non-human ancestors and cousins.Footnote 50

Reference to the ‘communicative behavior’ of non-human animals in this passage is telling. While Hockett allowed for continuity between animal communication and human language, he nevertheless saw the two as distinct. Doubling down on this point, he subsequently stressed, ‘The appearance of language in the universe – at least on our planet – is thus exactly as recent as the appearance of Man himself’.Footnote 51 Thus Hockett endorsed Darwinian continuity from apes to humans, while simultaneously highlighting the discontinuity between prehistorical and historical languages within the human species. Absent the tools of comparative reconstruction, how would research proceed?

Hockett crystallized and revised some of his ideas on the subject in a short paper on ‘The origin of speech’ for Scientific American a couple of years later. His comments at that time historicized the methodological divide between comparative and evolutionary linguistics.

There was at first some hope that the comparative method might help determine the origin of language. This hope was rational in a day when it was thought that language might be only a few thousands or tens of thousands of years old, and when it was repeatedly being demonstrated that languages that had been thought to be unrelated were in fact related. By applying the comparative method to all the languages of the world, some earliest reconstructable horizon would be reached. This might not date back so early as to the origin of language, but it might bear certain earmarks of primitiveness, and thus it would enable investigators to extrapolate toward the origin. This hope also proved vain. The earliest reconstructable stage for any language family shows all the complexities and flexibilities of the languages of today.Footnote 52

Even so, he found new cause for optimism in the empirical strides taken by researchers in complementary sciences of human prehistory, zoology and anthropology in particular. Taking up this expanded toolkit, he encouraged readers to stop thinking about prehistoric words and to start thinking about ‘basic features of design’ instead – features that might be ‘present or absent in any communicative system’ – human, animal or machine.Footnote 53

Whereas his 1958 textbook had presented seven such features, Hockett now introduced a new and improved list, thirteen items long (Figure 1).Footnote 54 This provided a way of simultaneously comprehending the evolutionary continuity and uniqueness of human language. Of these, an insistence upon arbitrariness – the arbitrary relationship between the signal or message and its intended referent – was key to the more complex features of displacement, productivity and duality of patterning. ‘The design-feature of arbitrariness’, Hockett wrote, has the disadvantage of being arbitrary, but the great advantage that there is no limit to what can be communicated about’. Here, then, was the idea that what differentiated human language from animal communication was, above all, its flexibility.

Figure 1. Hockett's ‘Design features of language’. Charles Hockett, ‘The origin of speech’, Scientific American (1960) 203, pp. 88–111, 7.

Hockett was by no means the first to emphasize the significance of the arbitrary relationship between the signifier and the signified. The idea was a cornerstone of conventionalist philosophies of language going back to Plato, and it was instrumental to the comparative method of historical linguistics. Without the arbitrary relationship between form and meaning, nineteenth-century philologists noted, there would be no grounds for attributing observed similarities among languages to historical relationship.Footnote 55 For this reason, onomatopoeic words were always among the first to be discarded from comparative-historical analyses. Though she claimed the mantle of comparative linguistics, Mickie Foster would bring sound symbolism back into her attempt to unravel Babel.Footnote 56

Vocalic gesture and Foster's primordial reconstruction

Foster – like Hockett, Darwin and others in this tradition – maintained biological continuity of descent. What set her apart was her commitment to the further continuity between prehistorical and historical phases within the development of human language. Though these ideas aligned closely with contemporary work in ethology and palaeoanthropology, they were a source of friction with her colleagues in linguistics. During the mid-1960s, for instance, when Foster first started working on the kinds of remote language comparisons that she believed would allow her to access prehistory, Harry Hoijer was ‘horrified, shocked, and surprised’. Haas, for her part, told Foster to set the project aside.Footnote 57 Foster later recalled that the slightest mention of correspondences between Old and New World languages would prompt area specialists to identify ‘some little minor flaw … and then they just kind of stop listening’.Footnote 58 Thus, even before she began to integrate comparative-historical linguistics with symbolic anthropology, Mickie was intellectually a member of the disciplinary fringe.

That said, Foster was exploring ‘long-range’ ideas in the midst of ‘a positive explosion of writing on the evolutionary foundations of language’ – the 1975 Symposium on the Origins of Language hosted by the New York Academy of Sciences is remembered as the high-water mark of this productive period of interdisciplinary research, though it was soon eclipsed by the neo-Darwinian turn brought about by E.O. Wilson's Sociobiology (1975) and Richard Dawkins's The Selfish Gene (1976).Footnote 59 The New York symposium was a who's who of philosophers, scientists and historians of language, including Chomsky, David Premack, Donald Davidson, Paul Kiparsky, Paul Kay and Philip Lieberman, among others. Research was presented on numerous fronts, including cognitive science, artificial intelligence, palaeontology, ethology, gestural communication, perceptual psychology, articulatory phonetics and neuroscience, in addition to remote comparative work on ‘protolanguages and universals’. For those speakers at the meeting who confined themselves to questions of a traditional comparative-historical nature, the most compelling connections between historical and prehistorical linguistics were taken to be a typology of change processes and the prehistoric reconstruction of ever more inclusive proto-languages.

Steeped in this interdisciplinarity, Foster's 1978 paper for Washburn and McCown figured language as a special case of culture, defined as the activity of expressive symbolization.Footnote 60 What Hockett and Ascher had earlier referred to as ‘the human revolution’ – articulate speech – Foster characterized as a ‘psychobiological event’, one depending on the twin cognitive functions of analogy and opposition. She defined the former as the mechanism of symbolic activity, a kind of metaphorical extension, and attributed the latter to Bloomfieldian structuralism, where ‘the rubric of sameness or difference in distinguishing emic from etic levels’ stood out as an ‘important analytical tool’. Foster lamented the way in which Chomsky had disparaged this discovery procedure, which for her was the key to understanding how languages make sense.Footnote 61

Remarkably, Foster argued that this cognitive bedrock could be reconstructed linguistically. Her argument did not depend on external appeals to anthropology and biology, though she felt that these did provide confirmation. Describing her methodology, she drew a straight and continuous line from history to prehistory:

The reconstruction presented here utilizes the methodology of comparative linguistics, developed during the 19th century in Indo-European studies, combined with the structural insights of 20th-century linguistics, in which relationships between parts are studied as a complex of systematic patterns, subliminal for language users but yielding their secrets to scientific analysis.Footnote 62

Foster's work on language origins was encouraged by the successful generalization of the comparative method from the study of written (Indo-European) languages to unwritten languages of the ‘world’.Footnote 63 The further extrapolation to unwritten proto-languages, though it ‘require[d] an assumption of monogenesis’, was unproblematic in her eyes.Footnote 64 Two chronological understandings made primordial reconstruction seem viable to Foster, where others had been much more pessimistic. First, she was working with a considerably shallower time depth than her colleagues had assumed. Citing Sapir as a representative of the old guard, she invoked recent studies of primate tool use and the cultural acceleration of the late Pleistocene to argue that

we have the emergence of language proper, not as utterance or signal, which must have preceded it, but as system or symbol. This hypothesis reduces the history of language to a period of approximately fifty thousand years; a time span with a far greater probability of reconstructive accessibility than the several million years postulated earlier.Footnote 65

Second, by shifting attention from form (phonology and morphology) to meaning (semantics), she was able to argue for a considerably slower rate of replacement than her predecessors had taken for granted. ‘Erosion’, the term she put to the rate of lexical replacement, was limited in the semantic domain by the ‘cognitive requirements’ of human vocabularies.

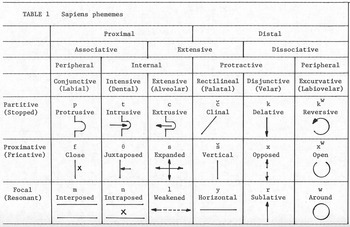

Armed with these metrics and methods, Foster ‘reconstructed primordial linguistic forms’, or phememes. She summarized her findings as follows:

Early linguistic symbols (phememes), apparently parental to all present-day languages, are reconstructed from a group of languages whose genetic relationship to one another is extremely remote. The reconstructed symbols are found to be nonarbitrary. Their motivation depends upon a gestural iconicity between manner of articulation and a movement or positioning in space which the symbol represents. Thus, the hypothesis presented here implies that early language was not naming in the conventional sense but representation of one kind of physical activity by means of another, displaced in time but similar in spatial relationship.Footnote 66

These results entailed several direct challenges to canonical linguistic theory, as Foster hastened to point out. Beyond the chronological points noted above and an esoteric internal debate about the genealogy of Hittite, she emphasized the need to rethink the Saussurian precept ‘that a meaningful segment of language is sign rather than symbol because the sounds by which it is conveyed are arbitrarily assigned’. This proposed revision in semiotic thinking was a distinct alternative to Hockett's design features of language.

Figure 2. Foster's ‘primordial phememes’. Mary LeCron Foster, ‘The symbolic structure of primordial language’, in Sherwood Washburn and Elizabeth McCown (eds.), Human Evolution: Biosocial Perspectives, Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin Cummings, 1978, pp. 77–121, 79.

Furthermore, Foster's primordial reconstruction delivered a direct challenge to Chomskian grammar: the notion ‘that the paradigmatic aspect of language is less interesting than its syntax’ became a ‘questionable assumption’ in the light of what she characterized as an ‘accidental discovery’ of linguistic monogenesis.Footnote 67 Chomsky left the table not long after with an attack on the relevance of animal communication. His parting words were sharp: ‘It's about as likely that an ape will prove to have a language ability as that there is an island somewhere with a species of flightless birds waiting for human beings to teach them to fly’.Footnote 68

Mickie Foster was not deterred. In her view, which directly contradicted Chomsky on acquisition and the brain, children learned language through embodied imitation. ‘What you need to think about is that human children … explore in every way with their whole body. Touching, feeling, testing, trying out and learning to do what their parents … or the people around them do’. This generalized to adults, she observed, who were particularly attuned to watching mouths, a way of learning to produce sounds. On this basis, she concluded that language was first and foremost a gestural system.Footnote 69 Countering those like Saussure who would argue for the primacy of vocalization, she linked gesture to the articulation of speech. ‘We don't think of [speech] as gesture because we think of it as something you use to make words, but you use the small muscles in your mouth in very fine-tuned ways in order to produce any kind of language’, she said. A special organ in the brain seemed totally unnecessary for the production of speech given that one does not ‘need a special organ to make hand movements’.Footnote 70

Here, then, are the foundations of Foster's approach to the reconstruction of ‘Primordial’ or ‘Sapiens language’. It was a theory that crossed over the arbitrariness threshold, restoring the isomorphic connection between form (vocal gesture) and meaning. For example, thinking gesturally about vocal articulation, she argued, ‘P’ might mean forward motion and ‘L’ might communicate looseness. ‘Your tongue is very loose when you pronounce L. So if we put P and L together, it's going to be a loose forward motion’. Linking this symbolic intuition to historically attested language data, she continued, ‘in English this PL comes from an Indo-European PL sequence which means flow, flowing, when in English it's FL, flow, fly, forward, loose motion’.Footnote 71 By making proposals like this, Foster united history and prehistory, extending the methods of comparative-historical linguistics from attested languages to then unknown relationships among reconstructed ancestral forms.

Foster subordinated this reconstruction to a broader investigation of the growth of symbols in a paper she developed through an interdisciplinary Wenner–Gren symposium on symbolism.Footnote 72 Her conviction that language was originally non-arbitrary was constant. An essential point, one that she developed in conversation with her daughter Melissa Bowerman's work on developmental psychology, was that phememes were action-oriented, not names.Footnote 73 Foster wrote in the proceedings she edited a few years later,

The meanings of recoverable roots are largely motional-relational, with implications of shape that derive from the direction in which the motion occurs, or as a result of the motion. While the words derived (by affixation) from these roots may represent objects … the original meaning of the root seems to have been more global and based on observed variations in movement rather than on object differentiation.Footnote 74

This attempt to identify historical universals completely discounted any Adamic recovery project.Footnote 75 It had more to do with tool use and painting than a fully ramified linguistic ontology, and it was something Foster believed had been gradually worked out over the course of the Palaeolithic. Foster labelled her brand of interdisciplinarity ‘connotative structuralism’ – an attempt to push beyond the denotative/referential register of mainstream linguistics to the covert web of figurative associations that she believed had been operative at the earliest instance of human language use in the Upper Palaeolithic. In sum, her struggle was with meaning, not form:

New ways of discovering meaning must be developed. Structuralism has pointed a way, but because structuralism has either geared itself only to the discovery of referential meaning, as in linguistics, or to a seemingly unrigorous postulation of connotative meaning, as in Lévi-Straussian structuralism, in which it appears possible to relate to, or derive anything from, virtually anything else … a connotative structuralism seems in danger of being discredited.Footnote 76

Such were the stakes. Foster's intervention in the language-origins debates was structural but mentalist, a departure from both Hockett and Chomsky. It was interdisciplinary, but primarily so on appeal to semiotic theory and developmental psychology at this stage, rather than studies of animal communication.

Foster continued to refine her theory and clarified its conceptual resources. Elaborating on a presentation delivered at the 1981 First International Transdisciplinary Symposium on Glossogenetics – which succeeded the New York symposium, was sponsored by UNESCO and launched the Language Origins Society – Foster wrote up an overview of her reconstruction for the Handbook of Human Symbolic Evolution.Footnote 77 By the mid-1990s, her method was more comprehensive and less dependent on the comparative method as a legitimating factor. ‘The evolutionary model for reconstruction’, Foster opened, ‘is an analogical model. Basically it relies on linguistic reconstruction by means of the comparative method, coupled with a strong reliance on the systematization of sound and meaning’.Footnote 78 Analogy was the cornerstone of this iteration of her theory and it continued to depend on a denial of the arbitrariness doctrine. Moreover, she imposed strict limitations on the nature and extent of her interdisciplinary appeal. For Foster, if the study of language origins was to be

biologically reinforced by examination of the behavior of other sentient creatures, the focus should be on the degree to which such creatures are able to classify their experience and extend their classifications by means of analogical inventiveness. If it is to be reinforced through archaeological examination of the remains of early man, these should be explored for evidence of the analogical organization of experience reflected in material culture. If it is to be reinforced by study of children's language learning, a major focus should be the child's progressive exploration of classification possibilities.Footnote 79

Foster was chiefly interested in classification, not communication. This was how she explained the development of progressively sophisticated symbolic activity. If there was discontinuity between historical and prehistorical linguistics, it had been imposed during the Neolithic period when phememes (possessing a non-arbitrary connection between sound and meaning) became phonemes (tending to obscure that connection through productive abstraction). Figuring out how and why that transition took place, she said, was the most difficult part of her theory. By the 1990s, she had come to the view that different language stocks fused the twelve original phememes she had reconstructed in highly characteristic ways – adding vowels to make vocalizations audible at a distance, for example – and that as these fusions proliferated, they obscured the original meanings of sounds.Footnote 80

Foster did not live long enough to realize her planned magnum opus on ‘Sapiens language’. That said, her prospectus for the project reveals a curious mix of influences – it is a relic of the synthesis achieved during the 1960s and early 1970s. She wrote,

Evolutionary understanding of linguistic prehistory requires no postulation of major genetic mutations, only a gradual conversion of signaled categorizations of happenings … Analysis of the recovered monogenetic lexicon illuminates evolutionary cognitive development, with progressive expansion of semantic differentiations, discovery of successive isoglosses marking phonological changes, and of semantic reorganizations on a deep, Whorfian level. That the roots of language are found to be categorically abstract rather than event-specific demonstrates that language did not begin as naming, as is commonly supposed, but instead converted early, abstractly categorical signaling to abstract relational reference: first perhaps as a mimetic transfer from whole- to part-body analogues, much as abstract whole-body analogues are displayed as spatial-visual representations in the bee-dance: for bees a complex, representational signal rather than a symbol, but suggesting an evolutionary means of hominoid, analogical spatial-relational progression from signal to symbol.

Foster remained committed to the ‘accidental’ discovery of linguistic monogenesis. A student of Homo loquens for over thirty-five years, she defined that creature as one who was, above all, organized and embodied.

Conclusion

Foster, like Joseph Greenberg, the Nostratic school, members of the Language Origins Society and other linguistic ‘long-rangers’, was a committed monogenist from the 1960s on.Footnote 81 She was arguing for an inclusive species-level genealogy throughout a period defined by profound ideological differences within linguistics and throughout the world. Continuity across the animal–human divide was something she felt could be safely taken for granted, a departure from Chomsky; continuity within the human family was a more pressing issue. More challenging still was demonstration of the uniformitarian continuity from history to prehistory. Maintaining a gradualist framework, and rejecting Hockett's arbitrariness threshold, this came with the resolution of language to a system of vocalic gesture.

This article has emphasized the contributions of a marginal figure in the twentieth-century history of evolutionary linguistics for three primary reasons. First of all, properly linguistic work on the origins of language is characteristically marginal – thus Foster is representative in her iconoclasm. Second, her discontinuous career path disrupts standard accounts of the twentieth-century institutionalization of American linguistics, which helps to explain how she came to her unique theory of language origins. Finally, the substance of her reconstruction of ‘Sapiens language’ underscores the enduring difficulties linguists have had with meaning through the second half of the twentieth century. Meaning has often been held constant and obscured in order to examine the development of linguistic forms. Foster's grounding in symbolic anthropology was deeply at odds with this approach to understanding diversity and the past.

The challenge that Darwin bequeathed to twentieth-century linguists was twofold, at least: how might one demonstrate continuity between animal communication systems and human language while, at the same time, linking the development of historical languages to the forms attributed to human prehistory? The lack of direct archaeological evidence on early human language has consistently vexed the intrepid researcher seeking to take these on. Where Darwin posited instinctive cries, Foster appealed to vocalic gesture. Without a ‘Wellsian time machine’, researchers in this tradition have had to marshal a wide range of partial explanations, to forgo ‘experiment in favor of logic’. In this sense, Foster's dilemma with respect to reconstructing phememes had much in common with the challenge Darwin faced in defending natural selection.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the leadership of the volume editors; the material support provided by the University of Pennsylvania and by the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine; and the insights shared with me by Alice Kehoe and Julio Tuma through generous personal communications.