The philosophical underpinnings of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) are often overlooked by academicians, trainers and clinicians in this field. CBT stands nowadays as the most empirically supported model of psychotherapy (‘the current gold standard of psychotherapy’; David Reference David, Cristea and Hofmann2018), embracing a large variety of intervention methods and techniques, which some authors have argued to hold contradictory assumptions about the centrality of key epistemological ideas. In fact, they have claimed that several differences between the waves of CBT are philosophical rather than empirical and agreed that clarity about the philosophical assumptions of CBT theory and practice has remained largely unexplored (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Hayes2019). The debate surrounding the philosophical foundations of CBT increased over the past couple of decades, having reached a provisional consensus that despite such differences in the philosophical tenets between some CBT models, ‘traditional’ and ‘third-wave’ techniques are compatible and may improve CBT interventions for some disorders (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008, Reference Hofmann and Hayes2019).

Despite its indisputable contributions, such discussion has been limited by two major shortcomings: first, an excessive emphasis has been placed on the confrontation between two CBT models (i.e. Beckian cognitive therapy versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)), while neglecting other traditional (e.g. rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT)) and acceptance-based (e.g. dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT)) models that contribute to the richness of CBT; and second, a simplistic comparison of the philosophical assumptions underlying traditional and third-wave models (e.g. critical rationalism versus functional contextualism) does not accurately reflect the epistemological complexity that fully characterises CBT. Therefore, this article aims to briefly review the philosophical roots that have underlain the evolution of CBT and to provide an integrative reflection on the cross-cutting philosophical tenets that have been consistently guiding the development of CBT since its origins to the current state of the art.

The ‘three waves’ of CBT

Behavioural therapy

Behavioural therapy is generally considered the first scientifically based psychotherapy. ‘Behaviourism’ in itself substantiates an intersection between philosophy (at the ontological, epistemological and axiological levels) and psychology, by rejecting introspective methods and seeking to understand behaviour solely by measuring observable events that support predictions that can then be tested experimentally. Behaviourism placed a huge emphasis on the contexts for human learning and development (illustrated by Watson's famous quote: ‘Give me a dozen healthy infants […] and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select’; Watson Reference Watson1930: p. 104), and was largely based on classical (Pavlov) and operant (Skinner) conditioning principles. These principles hugely influenced the pioneering (and often forgotten) work of Mary Cover Jones in fear desensitisation (dubbed by Wolpe – another prominent name in systematic desensitisation – ‘the mother of behaviour therapy’) and the psychotherapeutic work developed by Lindsley and Eysenck in the treatment of psychosis and neurosis respectively during the 1950s.

Cognitive therapy

The second wave is cognitive therapy, developed by Beck during the 1970s as a critical and scientifically based psychotherapeutic alternative to traditional psychoanalysis. The cognitive therapy model essentially asserts that maladaptive responses (i.e. psychopathology) to stressors/events are mediated by patterns of distorted and rigid thinking (e.g. dysfunctional schemata/beliefs, cognitive distortions and negative automatic thoughts), which need to be targeted in therapy in order to reduce symptoms and improve flexible functioning. It is extremely important to note that, although in some of his earlier works Beck stated that ‘alterations in the content of the person's underlying cognitive structures affect his or her affective state and behavioural pattern’ (Beck Reference Beck1979: p. 8), the interdependence between thoughts, emotions and behaviours was notably highlighted in his subsequent works (e.g. ‘the vicious cycle’; Beck Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985: p. 48). Also, in parallel with the classic Beckian model of therapy, other cognitive–behavioural approaches evolved during the 1960s and afterwards, including Ellis's rational emotive behaviour, which endorsed the claim that irrational beliefs about the self and the world (e.g. ‘I need to be liked and approved by everyone’, ‘If I don't perform well, it means I am a failure’) mediated the link between triggering events and psychopathological symptoms.

Acceptance-based therapies

Although rooted in the 1980s, the so-called third wave of CBT has gained pre-eminence over the past couple of decades (as in pop culture, (psychological) science is naturally attracted to ‘the next big thing’). This third wave reformulates and integrates previous generations of CBT, being particularly sensitive to the context and functions of psychological phenomena (and not just to their form – i.e. the form of such phenomena is not straightforwardly excluded), and thus emphasising: experiential strategies in addition to more direct/didactive ones; common issues for clinicians and patients (e.g. the ubiquity of human suffering); and the construction of broad, flexible repertoires, as opposed to the elimination of narrowly defined problems (Hayes Reference Hayes2004). Far from consensual, the ‘third wave of CBT’ appears to be an umbrella term to encompass a variety of CBT-based models (e.g. ACT, DBT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, behavioural activation), which tend to share some features, such as a distinctive focus on mindfulness, acceptance and the therapist's and patient's values (for a general review of the three waves of CBT, see Ost Reference Ost2008). Nevertheless, some authors (e.g. Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008) have argued that these characteristics have been part of CBT for a long time, even if treatments may differ in their theoretical grounds (Ost Reference Ost2008).

Common grounds in the philosophy of CBT

Limitations of the current debate

Although third-wave CBT has been characterised by openness to older clinical traditions (namely behavioural therapy), thus building on the first- and second-wave treatments, the confrontation between traditional cognitive therapy and third-wave CBT becomes salient when discussing the respective philosophical assumptions. For instance, when confronting essential features of traditional CBT approaches with acceptance and mindfulness-based CBT (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008), three aspects tend to be overlooked: first, second-wave CBT is equated to Beckian cognitive therapy and the illustration of third-wave CBT is limited to the ACT model, which results in the exclusion of well-known therapeutic models that decisively contribute to characterising each CBT wave (e.g. REBT, DBT); second, when describing the basic components of cognitive therapy (i.e. establishing a good therapeutic relationship; problem focus; identifying irrational thoughts; challenging irrational thoughts; testing the validity of thoughts; substituting irrational thoughts with rational thoughts and eliciting feedback), some of its essentials (e.g. the use of Socratic method in guided discovery) are not fully addressed or sufficiently emphasised; and third, the discussion of philosophical foundations underlying second- and third-wave CBT is limited to a mutually exclusive, two-branch division of such assumptions (i.e. rationalism versus contextualism), which does not provide an accurate depiction of the diverse philosophical roots of CBT.

Misconceptions about cognitive therapy

Despite its focus on cognitive restructuring, second-wave CBT did not discard the relevance of incorporating acceptance-based approaches in therapy. Based on his earlier writings, Ellis (Reference Ellis2006) has remarkably highlighted the striking similarities between mindfulness-based stress reduction and REBT, by reviewing the centrality of unconditional self-acceptance, unconditional other-acceptance and unconditional life-acceptance in REBT. In addition, it is worth noting that Beck et al (Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985) described strategies for ‘accepting the feelings’ (e.g. reducing anxiety about anxiety; reducing shame about showing anxiety; and active acceptance) when outlining an intervention protocol for ‘modifying the affective component’ in anxiety disorders (for a detailed description, see Beck Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985, pp. 232–240). Besides these two examples that pass apparently unnoticed, it should also be highlighted that DBT plainly incorporates cognitive modification procedures with core mindfulness skills training (Linehan Reference Linehan1993: pp. 144 and 358) in promoting the dialectics (e.g. through compassionate flexibility) between acceptance (e.g. mindfulness and distress tolerance) and change (e.g. emotion regulation and interpersonal effectiveness).

A final remark on common misconceptions about the second wave of CBT concerns the reductionist description of its fundamental process as ‘replacing irrational thoughts with rational thoughts’. When revisiting the classic principles of cognitive therapy (Beck Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985: p. 167), it appears evident that cognitive therapy is heavily drawn on collaborative empiricism (‘Principle 4: Therapy is a collaborative effort between therapist and patient’, p. 175) and on Socratic dialogue (‘Principle 5: Cognitive therapy uses primarily the Socratic method’, p. 178). Taken together, a major implication of these principles is that cognitive therapy is all about genuine guided discovery and not merely about changing thoughts and beliefs. Interestingly, this is akin to the therapeutic use of metaphors in ACT (Hayes Reference Hayes2004: pp. 653–654), where analogies such as ‘the person in the hole’ or ‘the polygraph metaphor’ are aimed at facilitating patient's ‘reperceiving’ (in this case, towards the insight: ‘control is the problem, not the solution’). Additionally, it should be highlighted that Beckian cognitive therapy integrates a strong behavioural component, as evident in the therapeutic procedures of ‘testing the validity of thoughts’ (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008), targeting cognitive avoidance, behavioural skills training and engaging in behavioural experiments or graded exposure (Beck Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985: pp. 258–287).

Diversity calls for complementarity

The ACT philosophy is described as post-Skinnerian and linked to radical behaviourism; in essence, the philosophical basis of ACT is functional contextualism, which is characterised by a focus on the whole event; a sensitivity to the context in understanding the nature and function of an event; an emphasis on a pragmatic truth criterion; and the delineation of specific scientific goals to which that truth criterion can be applied (Hayes Reference Hayes2004). The philosophical foundation of classic CBT, on the other hand, is critical rationalism, which assumes ‘that knowledge can only be gained by attempting to falsify hypotheses that are derived from scientific theories’ (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008: p. 12). However, CBT's philosophical foundations are originally more complex than such dichotomous classification.

According to Beck et al (Reference Beck1979: p. 8), the philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to stoicism (and related Eastern philosophies, such as Buddhism, which is explicitly acknowledged in the philosophical underpinnings of ACT and DBT). In fact, the famous quote by Epictetus (‘Men are disturbed not by things but by the views which they take of them’) has been used extensively to illustrate the epistemological stance adopted in the practice of CBT. Even though several therapeutic issues (e.g. the ubiquity of human suffering and its source in attachment; the centrality of mindfulness and valued action) are partially overlapping between ACT and Buddhist practices (Hayes Reference Hayes2002), ACT is based on functional contextualism and aims to promote well-being, whereas Buddhist philosophy and religious doctrines seek to promote spiritual awakening and enlightenment (Fung Reference Fung2015). It is also noteworthy that Stoics cultivated the therapeutic dimension of philosophy (including mindful attention, through a variety of ‘spiritual exercises’) from a rational perspective that informed the origins of CBT (Robertson Reference Robertson and Codd2019), whereas the Buddhist concept of mindfulness is inherently linked to the spiritual development of wisdom, compassion and ethics (Kang Reference Kang and Whittingham2010). These complementary differences remarkably illustrate the important role that philosophy and religion have traditionally played in the processes of healing and meaning-making (Robertson Reference Robertson and Codd2019).

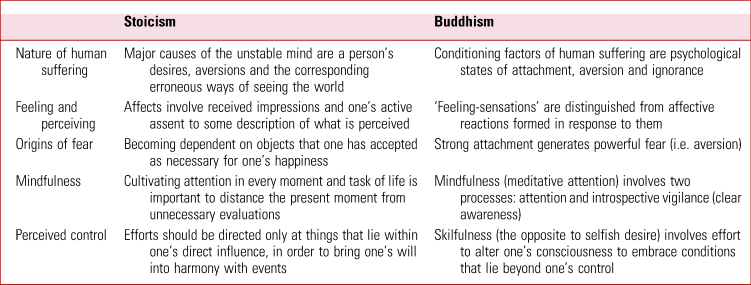

Moreover, the broad philosophical bases of CBT include the philosophies of Epicureanism, hedonism and existentialism (Murguia Reference Murguia and Díaz2015). Just like stoic philosophy is reflected in several core features of CBT (e.g. Socratic questioning, mindfulness, acceptance, empathic understanding; for a detailed review see Robertson Reference Robertson and Codd2019), existential concerns (e.g. death, responsibility, meaninglessness, isolation) are common themes in CBT (Heidenreich Reference Heidenreich, Noyon and Worrell2021). Specifically, existentialism (as developed by Kierkegaard, Sartre and de Beauvoir) examines the problem of the human condition from the experience of thinking, feeling and acting, while exploring the issues of meaning, purpose and the value of human existence. For this reason, one may reasonably argue that CBT has consistently valued (a) the role of context in shaping and understanding human behaviour (contextualism); (b) the cultivation of separating judgements from events (stoicism); and (c) the acceptance of responsibility for one's best efforts in living a meaningful life (existentialism). It bears noting that although stoicism, as a Western school of philosophy, differs in many stances from Buddhism (e.g. rationalist versus gnostic routes: even if both emphasise ethics, for instance, stoic ethics are based on using reason to free oneself from ‘passion’, whereas Buddhist ethics revolve around ‘karma’ when advising oneself against being ruled by desire), they should not be considered incompatible, since ‘differences in manifestation are to be expected when the same truths are approached from disparate sociocultural and historical starting points’ (Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2008: p. 41). Instead, striking similarities may be acknowledged between these two philosophical trends (Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2008; Sharpe Reference Sharpe and Davis2013), as briefly outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Similarities between stoicism and Buddhism in some themes related to cognitive–behavioural therapy

CBT clinicians and researchers who are capable of consistently integrating the philosophical assumptions of their models are better equipped to drive knowledge forwards and improve the effectiveness of their interventions (Hayes Reference Hayes and Hofmann2018). For instance, a patient suffering from panic attacks may benefit from psychoeducation about their anxiety and ‘decatastrophising’ (cognitive restructuring), before engaging in graded exposure (conditioned fear extinction), at the same time as learning to accept and tolerate moments of distress (mindfulness). Given the fact that clearly articulated combinations of approaches are viable and useful, the Inter-Organizational Task Force on Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology Doctoral Education recommended that all CBT programmes should place a greater emphasis on training in the philosophy of science (Klepac Reference Klepac, Ronan and Andrasik2012) – an initiative that sounds particularly important to prevent ad hoc eclecticisms that may result in confusing and inconsistent mixes of theories and therapies. Certainly, distinct philosophical perspectives can coexist and cooperate, bearing in mind that CBT is ample enough to accommodate such diversity within a clearly defined theoretical background, while agreeing on the practical importance of outcomes in psychotherapeutic work (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Hayes2019). Therefore, CBT research and clinical practice can be conducted at two mutually informative levels: a functional level that seeks to explain behaviour in terms of environmental elements and a cognitive level that aims to understand the mental mechanisms that mediate environmental influences on behaviour (Hayes 2018). In any case, a process focus (i.e. ‘process-based CBT’; Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Hayes2019) is likely to conciliate epistemological arguments into controllable empirical issues, explored in the context of different but complementary philosophical assumptions. Most importantly, clinicians should keep up to date with new developments in CBT (Hayes Reference Hayes and Hofmann2021), so they can be cognisant of its evolving richness and complexity, and cultivate mastery in applying various methods and techniques, which may be integrated in consistent intervention plans that are tailored to their patients’ needs.

Acknowledgements

I thank Prof. Dr Cristina Canavarro and Dr Ana Fonseca for their constant and wise support. I am also grateful to: Prof. Dr Ana Paula Matos, for her ongoing clinical supervision in CBT; Prof. Dr Luísa Barros and Prof. Dr Ana Isabel Pereira, for their encouragement to write about the philosophy of CBT; and Paula Atanázio-Martins and Dave Llanos, for their keen interest in discussing some of the key ideas that inspired this work. This article is dedicated to Prof. Teresa Matos Nogueira.

Funding

This study was supported by the Center for Research in Neuropsychology and Cognitive and Behavioral Intervention (UIDB/PSI/00730/2020) at the University of Coimbra.

Declaration of interest

C.C. is a member of the BJPsych Advances editorial board, but did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.