Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

2 During excavation directed by Dr Ann Ellison for the Committee of Rescue Archaeology in Avon, Gloucestershire and Somerset. Ian Longworth and Catherine Johns of the British Museum made it available to RSOT. For the site see A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines: Excavation of a Ritual Complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire: 1977–9 (1993), which contains an interim report on the inscribed lead tablets, 113–30. This tablet is noted on p. 129, as No. 50.

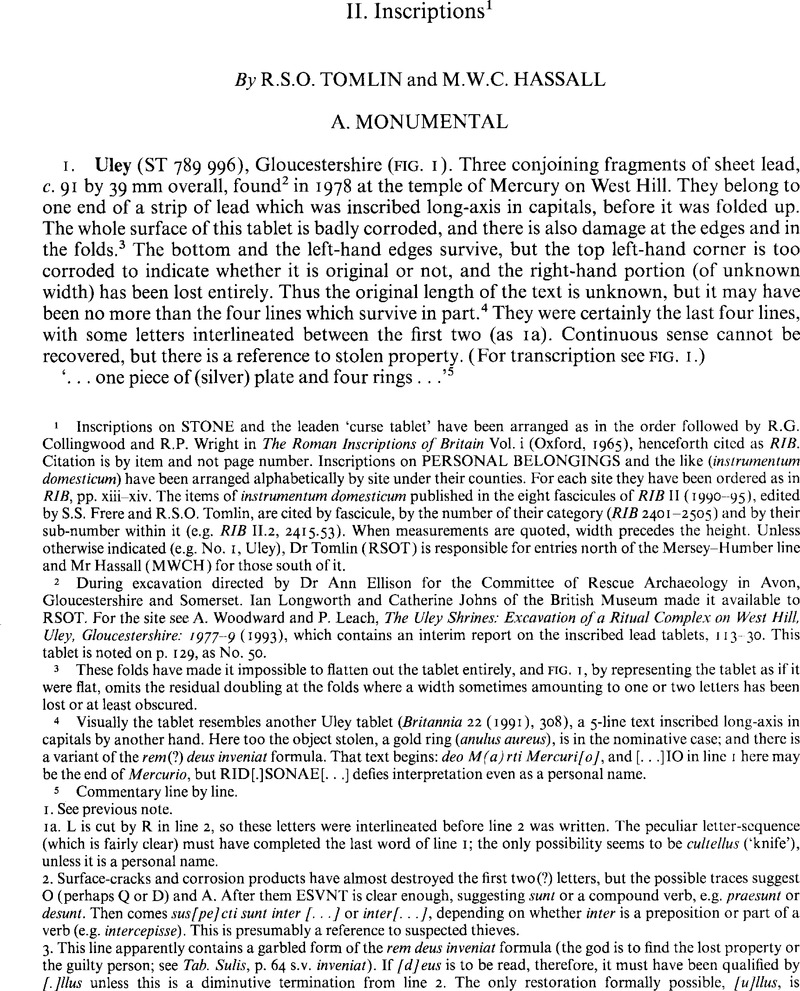

3 These folds have made it impossible to flatten out the tablet entirely, and FIG. 1, by representing the tablet as if it were flat, omits the residual doubling at the folds where a width sometimes amounting to one or two letters has been lost or at least obscured.

4 Visually the tablet resembles another Uley tablet (Britannia 22 (1991), 308), a 5-line text inscribed long-axis in capitals by another hand. Here too the object stolen, a gold ring (anulus aureus), is in the nominative case; and there is a variant of the rem(?) deus inveniat formula. That text begins: deo M(a)rti Mercuri[o], and […]IO in line I here may be the end of Mercurio, but RID[.]SONAE]…] defies interpretation even as a personal name.Google Scholar

5 Commentary line by line.

1. See previous note.

1a. L is cut by R in line 2, so these letters were interlineated before line 2 was written. The peculiar letter-sequence (which is fairly clear) must have completed the last word of line 1; the only possibility seems to be cultellus (‘knife“), unless it is a personal name.

2. Surface-cracks and corrosion products have almost destroyed the first two(?) letters, but the possible traces suggest O (perhaps Q or D) and A. After them ESVNT is clear enough, suggesting sunt or a compound verb, e.g. praesunt or desunt. Then comes sus]pe]cti sunt inter […], or inter]…], depending on whether inter is a preposition or part of a verb (e.g. intercepisse). This is presumably a reference to suspected thieves.

3. This line apparently contains a garbled form of the rem deus inveniat formula (the god is to find the lost property or the guilty person; see Tab. Sulis, p. 64 s.v. inveniat). If [d]eus is to be read, therefore, it must have been qualified by [.]llus unless this is a diminutive termination from line 2. The only restoration formally possible, [u]llus, is inappropriate to deus (‘any god’), so perhaps the scribe actually wrote [i]llus for ille. The space available to the left of LL suits I, not V. Since *illus is not a known ‘Vulgar’ form, it would be an error prompted by the ending of deus.

4. lami[l]la una. The scribe wrote I, not E. Since ‘one lamilla’ is coupled with ‘four rings’, it must be something valuable; presumably a mis-spelling of lamella in the sense of ‘(silver) plate’. Lamina and its diminutive lamella are used in the sense of ‘silver’, i.e. ‘money’ but not explicitly ‘coin’, just as Roman silver plate often carries a note of weight to indicate its value as bullion.

et anulli quator. The Vulgarism anellus < anulus is found, but anulli would seem to be another mis-spelling; the scribe evidently had trouble with his diminutives. Another Uley tablet (Britannia 23 (1992), 311, No. 5) writes Classical quattuor, but quattor and quator are a frequent Vulgarism, whence Italian ‘quattro’, Portuguese ‘quatro’ (etc.).Google Scholar

This ‘one piece of (silver) plate and four rings’, bullion in a convenient form, must be the property stolen. The nominative case is unusual but, as noted above, it also occurs in Britannia 22 (1991), 308 (Uley)Google Scholar, anulus aureus. The governing verb is lost in both, but it may have been pereo used as the passive of perdo, ‘lost’ in the sense of ‘stolen’; thus per[i]erunt is used of stolen gloves in Britannia 27 (1996), 439, No. 1 (Uley), where see the note on p. 441. For other curse tablets prompted by the theft of rings see RIB 306 (Lydney), anilum; Tab. Sulis 97, anilum argenteum, and perhaps 59, ANVL1S.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

6 During renovation and re-roofing, when plaster casts were made which are preserved in Gloucester City Museum, where Sue Byrne made them available to RSOT. There is an interim account, with a schematic drawing (fig. 6), in Glevensis 29 (1996), 16.Google Scholar

7 There would have been two rosettes within the pediment, balanced by a third, or more likely a crescent, above them at the apex. This format of a panel surmounted by a pediment between two rosettes, reminiscent of an altar, is found in three first-century tombstones from Chester: see RIB 502, 518 and 560, where Baty's drawings are incomplete, and reference should be made to R.P. Wright, Catalogue of the Roman Inscribed and Sculptured Stones in the Grosvenor Museum, Chester (1955), Pls XV (No. 48) and XVIII (Nos 62 and 64). The Gloucester text, without any Dis Manibus and concluding with H(ic) S(itus) E(st), is also first-century.

8 The handsome wide-branching Y is unique in Britain except for RIB 562 (Chester).

9 The width of the missing strip can be calculated from the certain restoration of the letters [O] in line 3 and [S] in line 4, of which no traces now remain, and by reconstructing the pediment. In line 2 the cast preserves only the vertical stroke of P and the second vertical stroke of H, without any trace of the various horizontal strokes, but Nymphius like Lusius can be restored with certainty. Nomen and cognomen are both well attested, and even in combination they are not distinctive, but they suggest Italian and/or freedman origin.

10 With the next three items by a local field-walker, in whose possession they remain. Jean Bagnall Smith, who is studying the finds from the site, made them available to RSOT.

11 For the fragment of a similar A from the site, see RIB 238 (a).

12 The apex is too broad for A. For a complete M in this style from the site, see RIB 239 (a).

13 The first surviving letter could also be A, but the sequence -AO- can be rejected. There is a space between S and A, but this is probably due to a miscalculation while working in reverse, as indicated by the progressive congestion of ADO. The other votive plaque from Wood Eaton (RIB 236) concludes with EDO, a coincidence that suggests a shared donative formula, e.g. do(num) or do(no). There are Celtic personal names in -edo, it is true, but not in -ado, whereas the feminine Mossa is quite possible; compare Mossiu(s) (RIB II. 1, 2409.25) and Moxi (genitive, RIB II. 7, 2501.397), and Holder s.vv. Mossus, Moxius.

14 The fort was usually known as Little Chesters until Hedley built the nearby cottage of ‘Chesterholm’ (now the Museum) in 1831. RIB II followed RIB I in using this nineteenth-century name, but the fame of the Vindolanda Tablets, not to mention the work of the Birleys and the Vindolanda Trust, has re-established the primacy of the ancient name.

15 With the next item during excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Robin Birley. Anthony Birley sent photographs and other details of them both, including an advance copy of his paper (see above, pp. 299-305).

16 There is a space between lines 2 and 3, and line 9 is inscribed below the panel. The irregular spacing of the leftward margin suggests that the text was centred line by line. In line 6, T is notably taller than the rest of the line, and is placed (for emphasis?) to the left.

17 This important text is fully published by Anthony Birley (see above, pp. 299–305), who restores it partially and finds a reference to warfare early in the reign of Hadrian. (The use of abbreviated D(IS) M(ANIBVS) with STIPEND1ORVM unabbreviated suggests a date quite early in the second century.) Like him we note the anomalous T in line 6, and only add the conjecture that it may be a Latin annotation (nota militaris) equivalent to the Greek letter theta [TH], meaning ‘died (in action)’, for which see Watson, G.R., ‘Theta Negrum’, JRS 42 (1952), 56–62. According to Isidore of Seville (quoted ibid.), Greek tau [T] marked the names of ‘survivors’, but the aspirated Greek letters theta and phi tend to be transliterated as T and P, and in a contemporary Latin list although from Egypt (Fink RMR 34) soldiers who died (in action) are marked as TE for TETATI (ibid., and compare RMR 63, ii 11, THETATI still with Greek theta).Google Scholar

This explanation of T is conjectural, and it would follow that line 5 contained not only the term of service but the age at death, in the form [STIPEN] [DIORVM [numeral ANNORVM numeral], entailing a shorter line-length than Birley's. Lines 3-4 would then read CENTVR[IO] COHORTIS I | TVNGR[ORVM STIPEN], and it might be objected that the word cohors is almost always abbreviated, but this is equally true oicenturio. In line 2 it would seem that only a cognomen has been lost entirely.

18 The inscribed letters and the phallus should probably be taken together, but the expansion of HP III can only be conjectured; possibly h(abet) p(edes) III, ‘It is 3 ft long’.

19 During excavation by the Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit directed by Alex Jones. Annette Hancocks made it available to RSOT.

20 The graffito is complete, and is probably the owner's name, M(…). Its presence underneath was indicated by two notches incised in the chamfer between wall an d base, coinciding with the apex of the second and the fourth stroke of M.

21 By D.F. Browne, in whose possession it remains. Information and a drawing were sent by Judith Roberts of the Cambridge County Council Archaeological Field Unit.

22 By Mr Gordon Sandland with a metal-detector, and donated by him to Cheshire Museums Service (accession no. 1993.36). It has been fully published by S. Penny and D.C.A. Shotter, who also cite the next item. See their note ‘An inscribed Roman salt-pan from Shavington, Cheshire’ in Britannia 27 (1996), 360–5, with pl. XV.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23 The fragmentary letter before C looks like P, but the editors rightly prefer S reversed: it would resemble the S in RIB II.2, 2416.2. Note that N is also reversed, as it is in RIB II.2, 2416.2 and 3. Although there are Greek personal names in -opus, [EPIS]COPI is the inevitable restoration. This brings into question the two similar brine-pan inscriptions already cited, CVNITVS CLER and CVNITI CLE, where by analogy with [EPIS]COPI, the expansions CLER(ICVS) and CLE(RICI) should now be preferred. The personal names Viventius and Cunitus require a Roman date for the pans, which would otherwise be doubtful, since ownership(?) by a ‘bishop’ and a ‘clergyman’ is anomalous.

24 ‘During building on Castle c. 70 m north of the church’: Petch, D.F. in Harris, B.E. (ed.), VCH Cheshire I (1987), 201–2, with fig. 32.2.Google Scholar

25 By analogy with Cuniti (RIB II.2, 2416.3), this would be a Celtic personal name in the genitive case. Veluus is not attested, but note its feminine counterpart Velua (RIB 688).

26 Halo Vecchi Ltd, London, coin auctions 5 March 1997, Lot 991 (illustrated in the catalogue). John Casey brought the auction to our attention, and the auctioneers sent a copy of the catalogue to RSOT.

27 For another example see RIB II. 1, 2411.41 (Ickham), with note there of parallels. See further Still, M.C.W., ‘Parallels for the Roman lead sealing from Smyrna found at Ickham, Kent’, Arch. Cant. 114 (1994), 347 56.Google Scholar

28 ‘The traditional identification of Counnus with Canvey is based on no more than a superficial resemblance’: Rivet and Smith, PNRB, 146.

29 By Mr and Mrs Lewin, in whose possession it remains. Information from Pam Gilmour who also provided rubbings.

30 The Vulgar Latin verb involare (‘steal’) is frequent in ‘curse tablets’ from Britain. It is often found with the formula si servus si liber (cursing the unknown thief ‘whether slave or free’), which may have preceded involat here.

31 With the next item during excavation of a house in Insula IV.3 by the Cotswold Archaeological Trust directed by C. Bateman. Details from Neil Holbrook.

32 Similar to RIB II.5,2489.21D.

33 Similar to RIB II. 5, 2489.21E.

34 During excavations directed by Mr E.G. Price, who sent details and a drawing.

35 During excavations by the Cotswold Archaeological Trust directed by Neil Holbrook, who sent a photograph and other details.

36 ER and EL are ligatured. Three identically inscribed ‘knee’ brooches have already been found in Britain: RIB 11.32421.56,57,58.

37 During excavation by the Welwyn Archaeological Society directed by Tony Rook, who provided rubbings and a drawing.

38 During excavation of the Roma n cemetery directed by Rosalind Niblett for St Albans District Council. Mrs Niblett provided rubbings and drawings of this and the next two items. For the site see R. Niblett, The Excavation of a Ceremonial Site at Folly Lane, Verulamium, Britannia Monograph No. 14, in press.

39 This and the previous two items are all sherds from similar samian bowls (Drag. 18/31) inscribed with the same name. Since all three were residual in the contexts in which they were found, it is likely that they once belonged to a set.

40 Analysis by Mike Cowell at the British Museum Research Laboratory shows it to be tin, 47%; lead, 53%; traces of antimony (less than 0.5%).

41 With the next item by Richard Hill, in those possession they remain. Mr Hill drew our attention to their discovery. Jenny Hall, Roman Curator at the Museum of London, supplied tracings and photographs, and made the ingots available. They will be published by her and Cheryl Thorogood, together with the ten previously known examples (RIB II.1, 2406. 1–10). Stamps (a) and (b) appear to come from the same die as RIB II.1, 2406 (a); stamps (c) and (d) from the same die as RIB II.2, 2406 (b).

42 The last letter appears to be complete and not part of the letter W (omega), but was presumably intended for omega, (a) and (b) are not from the same die as RIB II.12, 2406 (d), which is not illustrated there; for a drawing see RCHM, London iii, 175, fig. 85(d).Google Scholar

43 During excavations by the Museum of London's Department of Urban Archaeology and the City of London Archaeological Society directed by Gustav Milne: see Milne, G. amd Wardell, A., ‘Early Roman development at Leadenhall Court’, London and Middlesex Arch. Soc. Trans. 44(1993), 23–169, esp. 93 an d fig. 53.138.Google Scholar

44 The final letter could be u, for u[s], but it looks more like 0. (It is formed thus in contemporary stilus-tablet texts.) It somewhat resembles the letter before S which has been cut by the left-hand-edge, suggesting that ‘Saturninus’ is a cognomen preceded by a nomen with the same case-ending. Domitian's colleagues in the ordinary consulships of 87 and 92 were both called ‘Volusius Saturninus’, and given the archaeological context and the ablative(?) case-ending, it is possible that this graffito is part of a consular date.

45 During the excavation by the Settle Caves Exploration Committee and the British Association directed by Professor William Boyd Dawkins, for which see Dearne, M.J. and Lord, T.C., The Romano-British Archaeology of Victoria Cave, Settle. Researches into the Site and its Artefacts (BAR British Series, 1998, forthcoming). The sherd passed to the former Giggleswick School Museum, then the former Pig Yard Club Museum, and is now owned by Mr Lord. Dr Dearne sent details including a photograph.Google Scholar

46 Only the end of the first letter survives, a diagonal stroke; but since it must belong to a vowel, open A should be restored. For the Celtic name Annamus/Adnamus see Holder, s.v. Adnamius. It is local to Noricum; ibid., and G. Alföldy, Noricum (1974), 232. This is the first instance from Britain, but also in the north-west note Annamoris husband of Ressona (RIB 784, Brougham Castle)Google Scholar, names which also suggest Noricum (Alföldy, 236, with CIL iii 3377). Note also RIB 778 (Brougham Castle), an altar dedicated by Ann[…].Google Scholar

47 Italo Vecchi Ltd, London, coin auction 5 March 1997, Lot 993 (illustrated in the catalogue).

48 Italo Vecchi Ltd, London, coin auction 5 March 1997, Lot 994 (illustrated in the catalogue). The catalogue entry says ‘Found in Dorset’, but this has probably been repeated in error from Lot 991 [our No. 14, Dorset]. Military lead sealings are almost always found in northern Britain, and one would expect die-duplicates in the same auction to share a provenance.

49 Italo Vecchi Ltd, London, coin auction 5 March 1997, Lot 992 (illustrated in the catalogue).

50 In view of the seal-cutter's attention to medial points, it would seem that the centurion's name was Ag(…), not A (…) G(…). The most likely cognomina are Agilis, Agricola or Agrippa.

51 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Robin Birley, who made this (inv. no. 6324) and the next two items available.

52 The last two letters in line 3 resemble LL, but they are worn, an d there is a faint trace of the upper curve and diagonal downstroke of R (engraved in line 2 with a heavy bottom-serif), while a comparison with the angular P and R suggests that C was engraved quite square. Epigraphic dedications to the Parcae are found in Gallia Cisalpina and Narbonensis as well as in the Rhineland, the centre of the Matres cult, but to identify the Parcae explicitly as Matres may be peculiar to northern Britain; thus in RIB 881 (Skinburness) and 951 (Carlisle).

53 The width includes a projecting tenon of 50 mm to the left of ATTO. Compare the oak board ‘probably once the lid of a chest’, inscribed in capitals apparently with a personal name, in Birley, E., Birley, R. and Birley, A., Vindolanda Research Reports II (1993), 83, with pl. XXVI.6.Google Scholar

54 The A has no cross-bar, and the cross-bar of both Ts was incised with a single stroke. The name Atto is typical of Gallia Belgica and Upper Germany: see Alföldy, , Epigraphische Studien 4 (1967), 10. The plank comes from the waterlogged levels of the Flavio-Trajanic forts, and it is tempting to connect it with the writing-tablets. There is a decurion called Atto in Tab. Vindol. II. 345 (cf. 308), but on balance it looks as if he belongs to another unit. Atto also occurs at Vindolanda as a graffito on a samian vessel of c. 80–110 (RIB II.7, 2501.79).Google Scholar

55 Inv. no. VX 87. In line 1, the first stroke of N is detached, but N (not V) is guaranteed by the name Nestor, for which see RIB II. 7, 2501.409 with note (where the reference should be to RIB II.6, 2494.156). Line 2 ends with some angular strokes lightly incised, which seem to be unrelated to the firmly incised strokes of the rest of the graffito. The second letter of line 2 is evidently an unfinished H. A personal name *Chacaus (genitive CHACAI) is not attested, but for another Germanic name in Ch- from Vindolanda (Chrauttius) see Tab. Vindol. II. 310 i.1 with note. In line 3 the first stroke of A was apparently cut twice; it does not look like a centurial sign. The name Albinus is common. Why the bowl was scratched with three names is not clear: they may have been joint-owners, or successive owners, or perhaps one of the genitives (presumably CHACAI) was a patronymic.

56 During field-walking by Edward Shawyer, North Oxon Field Archaeology Group. He brought it to the Ashmolean Museum for identification, where Arthur MacGregor made it available to RSOT.

57 In line 1, only the vertical stroke survives of a third letter, possibly N. In line 2, VII is followed by a loop and part of N(?); but the sequence VER is so common in personal names that it is tempting to read the loop (etc.) as part of a cursive R. Since lines 1 and 2 seem to belong to the same graffito, it looks as if the owner of the vessel had two names, nomen and cognomen, or perhaps name and patronymic; [AN]TON[IVS ][SE]VER[VS] would fit, but this is only a possibility.

58 With the next five items (respectively inv. nos 5051, 605, 671, 1, 610, 69) during excavation by the Oxford Archaeology Unit directed by Paul Booth. Jeremy Evans made them available to RSOT, as well as a coarseware sherd (inv. no. 3336) with isolated letters, and eight others with possible marks of identification. Dr Evans notes that of 46,000 sherds excavated, these are the only ones to be ‘inscribed’. For an interim report on the site, see Britannia 23 (1992), 287.Google Scholar

59 Probably complete, like the previous item, but by another hand.

60 The first three letters are damaged, and the reading is not certain, but apparently a genitive case-ending […]end(a) e or […]endii.

61 Probably an indication of weight or capacity. For similar graffiti see RIB II.8, 2503.47 (etc.).

62 With items Nos 3–6 above. Jean Bagnall Smith made it available to RSOT.

63 For many similar examples, see RIB II. 3, 2440.

64 During excavation by Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit directed by Peter Leach. Lynne Bevan made it available to RSOT. For other inscribed objects from Fosse Lane, see Britannia 24 (1993), 319–20, Nos 20–22; 26 (1995), 383, Nos 16–17.Google Scholar

65 There is an incised roundel below the legend, which corresponds to the two roundels on each shoulder of the bezel. Memor is a cognomen, and even a cult-title of Minerva at a shrine in north Italy (cf. ILS 2603, a votive brought back from Britain), but here it is probably an adjective understood by the donor of the ring presumably, and by its wearer; either (sis) memor (mei), ‘Remember me’, or (sum) memor (tui), ‘I remember you’. The latter is perhaps to be preferred, in view of the rings inscribed MEMINI TVI (CIL xiii 10024.71 (b) and (c), ‘I remember you’), and MEMINI TVI MEMINI ET AMO (ibid., 72, cf. 73, ‘I remember you; I remember and I love (you)’).

66 During excavation for Yeovil Town Council directed by Radford, C.A. Ralegh: see his ‘The Roman site at Westland, Yeovil’, Proc. Somersetshire Arch, and Nat. Hist. Soc. 74 (1928), 122–43, esp. 143 with pl. H. 13. The sherd was noticed in the archaeological collections of the Museum of South Somerset, Yeovil, by James Gerrard, who sent a drawing and other details.Google Scholar

67 During damage assessment by the Central Excavation Unit. Stéphane Rault made it available to RSOT.

68 The stamp is not recorded, but it may be related to the incuse LHS stamps found at Minety and other sites in the Cirenccster area (RIB II.5, 2489.21). If so, it would have been of the form [.]HI, perhaps even [L]HI, being the initials of the tilery-owner. H(…) would then be a nomen gentilicium shared by father and son, or by two brothers, or by master and freedman, or by two freedmen; cognomen and perhaps praenomen would have distinguished them.

69 Where Bob Trett made it and the next item available to RSOT. The date and circumstances of discovery are not known.

70 […]V may be a separate graffito, since it is rather larger, although followed by an apparent medial point. The final I is only half-size, and is not followed by S.

71 This might be a Roman name abbreviated to three initials, but since O is smaller and slighter than the well-formed R, and the apparent medial point may only be casual damage, there are two other possible readings: either […]or or two graffiti, (i) […]O and (ii) R.

72 Nollé, J., ‘Militärdiplom für einen in Britannien entlassenen “Daker”’, ZPE 117 (1997), 269–74 (with an addendum by M. Roxan, 274–6). For the sequence of governors and their terms of office, see A.R. Birley, The Fasti of Roman Britain (1981), 100–12. We thank Professor Birley for discussing this question with us.Google Scholar

73 The left-hand portion was already lost when Horsley saw the stone, bu t its approximate width (3–4 letters) can be deduced from the sure restoration of [IMP] in line 1 and of [LEG] in line 3; while [LEGA] has probably been lost from line 5, if we assume this line was oddly spaced. In line 4, Horsley read […]IICNC.IR[…], and it is tempting to emend [.]IR[…] to [G]ER[MANO], but the drawing indicates too little space for [MANO]; and IICNC cannot be emended to TREBIO. The restoration is rightly rejected by Nollé (see previous note), 271, n. 10. Instead, the spacing suits an emendation of [.]IR[…] to [N]EP[OTE], E being damaged, and P having an apparent ‘tail’; while [3–4]IICNC is quite acceptable as [A PLA]TORIO, if Horsley read the end of A and a damaged T as II, helped by II immediately above in line 3, and mistook two incomplete Os for Cs, and RI with their two verticals and a diagonal for N.

74 Clarke, L.C.G., ‘Roman pewter bowl from the Isle of Ely’, Proc. Cambridge Antiq. Soc. 31 (1931), 66–75. Burkitt's reading (ibid., 72-3), with its reference to a bishop and clergy, is palaeographically impossible; but Minns (ibid., 73-5), who ‘ultimately’ reads super(a)ti sic patientia, has observed the graffito accurately and finds convincing parallels for the script. It would now be called New Roman Cursive.Google Scholar

75 By RSOT in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge (accession no. 1922.753), where Dr Chris Chippendale made it available.

76 The decoration incised on the upper side of the flange, which includes a Chi-Rho, is now quite worn. The bowl may also have been cleaned after it was found, while it was still in private hands in the nineteenth century: some darker patches underlie the grey patination, as if they are the residual surface. So gentle abrasion has probably removed some horizontal strokes in the graffito. Thus, although the context guarantees u in super and the first a in patientia, there is no surviving trace of the rightward curve of the first downstroke of u, nor of the second stroke of a. If a was ligatured to the following t, this would explain why the cross-bar of t begins only at the downstroke. In super, the r has evidently lost its tail.

After superti, there are three problematic letters which are not resolved by the context. The first is a long downstroke topped by a short diagonal which seems to be deliberate, so it looks more like s than i or a defective p. The second letter was read as i by Minns, but elsewhere the scribe writes a ‘long’ i, which this cannot be. It looks more like the first stroke of a defective letter: a perhaps, but less likely e or t, which might have been ligatured to the third letter, which might then be s, but looks more like c.

Patientia, a moral quality, is also acceptable as a ‘late’ feminine personal name formed like Viventia (e.g. RIB II.2, 2417.35) from a present participle: Kajanto (Cognomina, 259) notes examples of Patiens from which it derives, and even a fifth-century Patientius. It is suggestively Christian, and in this context the woman Patientia can be seen as a Christian. Conjecturally Patientia is preceded by a blundered Superstes or (better) Superstitis, ‘Patientia the wife (or daughter) of Superstes’.

77 Accession no. 980 404. Information from Elizabeth Whitbourn, who sent a photograph, a drawing and other details. See H.M. Larner, Busbridge: Godalming, Surrey (1947), 81–2; and for the eighteenth-century collection to which it belonged, Britannia 5 (1974), 463, n. 11.Google Scholar

78 As read by CIL, but with the missing letters bracketed, and all medial points noted. This imperial slave derives his second cognomen Terpnianus from a previous owner, perhaps the famous Neronian citharoedus Terpnus: see H. Chantraine, Freigelassene und Sklaven in Dienst der römischen Kaiser (1967), 337, No. 313.

79 It was offered by Italo Vecchi Ltd, London, in their coin auction of 5 March 1997 as Lot 997 (illustrated in the catalogue), and was bought by the Museum. Information from John Casey and Lindy Brewster.