Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by CollingwoodR.G. and WrightR.P. in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by TomlinR.S.O., WrightR.P. and HassallM.W.C. in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB I (1–2400) and III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB I, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

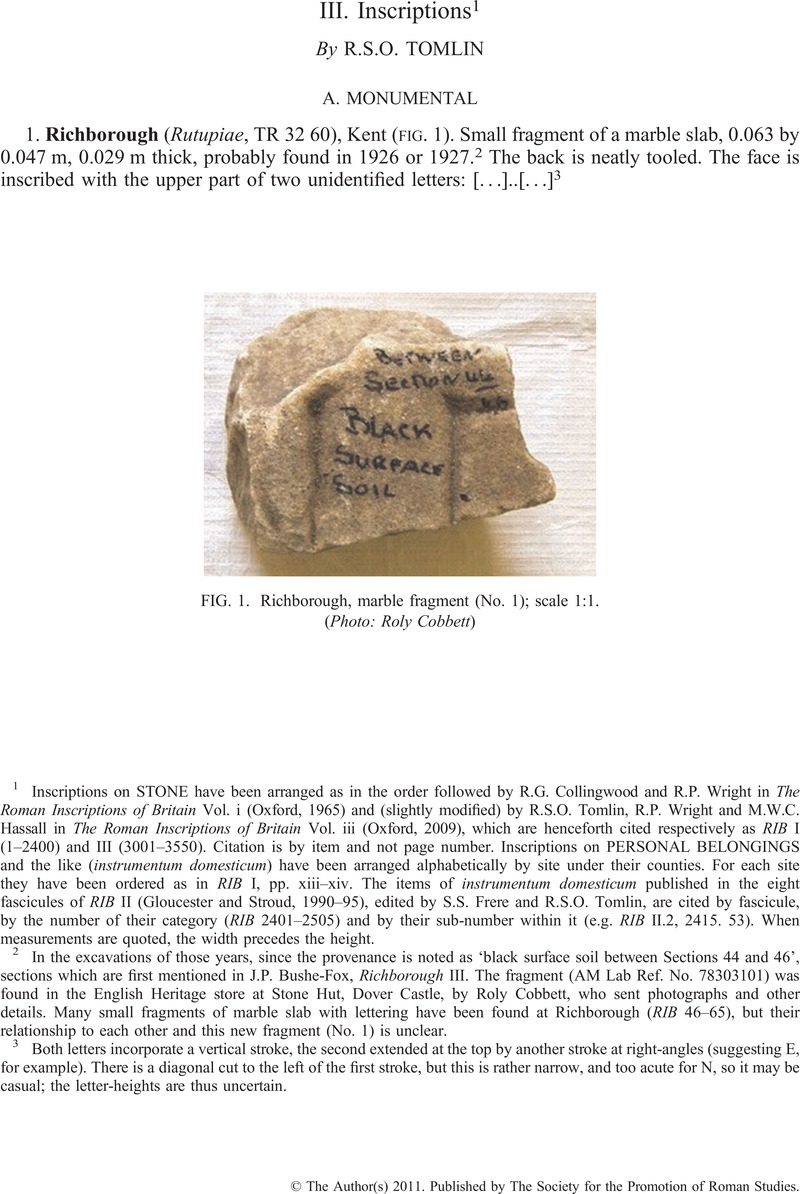

2 In the excavations of those years, since the provenance is noted as ‘black surface soil between Sections 44 and 46’, sections which are first mentioned in J.P. Bushe-Fox, Richborough III. The fragment (AM Lab Ref. No. 78303101) was found in the English Heritage store at Stone Hut, Dover Castle, by Roly Cobbett, who sent photographs and other details. Many small fragments of marble slab with lettering have been found at Richborough (RIB 46–65), but their relationship to each other and this new fragment (No. 1) is unclear.

3 Both letters incorporate a vertical stroke, the second extended at the top by another stroke at right-angles (suggesting E, for example). There is a diagonal cut to the left of the first stroke, but this is rather narrow, and too acute for N, so it may be casual; the letter-heights are thus uncertain.

4 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust (SF 13,784). Robin Birley made it available at Vindolanda.

5 All that survives of the third letter is the lower part of a vertical stroke, so it cannot be O or A, which eliminates any dedication to a god or goddess. The axis of the lettering is not parallel with the top (squared) edge; this, and its poor quality, suggests that it was incised at the quarry before the slab was squared up as building material.

6 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust (SF 14,831). Robin Birley made it available at Vindolanda.

7 In line 2, L instead of I would give a plausible sequence, but there is no sign of the horizontal stroke. V is scored horizontally across the top of its second (vertical) stroke, whether casually or to suggest a serif, or even as ligatured VT or VTE. Like the previous item, this is probably part of a quarry-face inscription.

8 It was noticed in the Clayton Collection by Georgina Plowright, who made it available at Corbridge Roman Site where it is now stored. It is uncatalogued, and apparently unmatched by any inscription in RIB, but was presumably found at one of the sites owned by Clayton, such as Chesters, Carrawburgh, Housesteads or Vindolanda.

9 The cutting is competent, but not of high quality. The letter is most likely to be C or G, since S would be too large, and O (or Q) excluded by the steady narrowing of width. In the top line of what was evidently a large building-inscription, C might well be the initial letter of Caesar (etc.).

10 With the next item and an altar-base nearby (but not inscribed) during excavation for East Lothian Council by AOC Archaeology, directed by John Gooder who made them available, together with his Lewisvale Park, Musselburgh: Excavation Data Structure Report (AOC Archaeology, 2010). The altars had been carefully buried side by side, face-down in a shallow pit. They are now in store with only the faces accessible, and the adhering soil has deliberately not been removed, so that when they are conserved it will be possible to recover further traces of colouring (etc.). They have been discussed with Fraser Hunter, who with Lawrence Keppie has already made a preliminary assessment and will lead the team responsible for full publication. Photographs and drawings here (figs 5 and 6), like the accompanying description and commentary, are therefore provisional.

Both altars were dedicated by the same officer to closely related deities, and the carving and lettering are evidently by the same hand(s), so there is probably no significance in the different colours of the sandstone. No. 6 is more orange than No. 5, but geologically they could both have come from the same quarry.

Inveresk is already noteworthy for two altars dedicated by the imperial procurator of Britain (RIB 2132 and III, 3499) and the tombstone of an eques singularis (Britannia 39 (2008), 372, No. 5Google Scholar) which may imply the presence of the imperial governor.

11 Letter-heights: 1, 50 mm; 2, 48–50 mm; 3, 45–48 mm; 4, 42–45 mm. The lettering, although not yet cleaned, seems to be well drawn and executed, but line 2 shows signs of crowding towards the end (notably in the diminutive O), although two-fifths of the panel was not used. S in line 3 is still obscured, but the reading is confirmed by the text of the other altar (No. 6). In contrast to No. 6, however, there is apparently no use of medial points, nor any centurial sign below line 4 despite there being ample space for it, but these apparent omissions must be confirmed after cleaning.

DAEO for deo is ‘hypercorrect’, and in Britain occurs only at Leicester (Britannia 40 (2009), 327, No. 21Google Scholar); it is rare elsewhere (CIL v 8136; xiii 41 and 5047; ILS 9087). The name of Mithras is sometimes spelled with Y instead of I (in Britain see RIB 1395 and 1599), and is sometimes abbreviated to the initial letter M where the formulation (for example deo invicto) and the context made the dedication obvious (in Britain see RIB 1544 and 1545; but in 1082 this is far from certain). The abbreviation to MY is most unusual, but also occurs in AE 1974, 477 (Noricum).

The attributes on either side of the die suggest Apollo, who is explicitly identified with the Unconquered Sun and Mithras in the Rudchester mithraeum (RIB 1397). Another altar from Inveresk (RIB 2132) was dedicated to Apollo Grannus.

The dedicator was a centurion and a Roman citizen, and thus likely to have been legionary, especially since his altars are of such outstanding quality. The form of A in line 1 (and probably in 3 and 4), which also occurs in No. 6, line 3, is also significant: with its angled cross-bar, it is peculiar to distance slabs of the Twentieth Legion on the Antonine Wall (RIB 2197, 2198, 2199, 2206, 2208 and III, 3507), and is found elsewhere in Britain only at the legion's base of Chester (RIB 461 in Greek, and 497). This strongly suggests that he was a centurion in the vexillation of that legion responsible for building part of the Wall, and that his altar is contemporary with this work in the early 140s. His post at Inveresk is unstated, but presumably he commanded a legionary detachment stationed there (compare Maximius Gaetulicus at Newstead, RIB 2120), or was acting-commander (praepositus) of an auxiliary unit in garrison.

Statistically his gentilicium is very likely to be Cassius, since this Italian and provincial nomen is so widespread, especially in Cisalpine Gaul according to TLL Onomasticon, but a few rare nomina are also possible, for example Castricius. His cognomen was probably Flavus, Flavinus or Flavianus, but Flaccus is also possible. He is otherwise unknown in Britain, and apparently not attested elsewhere; he cannot be identified with T(itus) Cassius Flavinus, centurion of Legion X Gemina buried at Tarraco (CIL ii 4151), nor with Cassius Flav[…], centurion of Legion XV Apollinaris at Carnuntum (CIL iii 4456), since this legion had left before a.d. 117. It is strange that G(aius) Cas(…) Fla(…) should have abbreviated his name in both inscriptions to this extent: in No. 6, space was limited, but it was ample in No. 5. However, like his fellow-centurion Maximius Gaetulicus at Newstead (RIB 2120), he also did not identify his legion; and he abbreviated the god's name as well.

12 Letter height: 33 mm. The first three letters of SOLI are still covered by dried mud, but in view of the radiate head of Sol below there are sufficient surface traces to read them with confidence. Only the vertical stroke of L in FL[.] is visible, and it is followed by space for one letter and a medial point; but the reading can be restored from No. 5 (above). For the dedicator's name and rank, see previous note. Similar but less well executed provision for illumination from behind is found in one of the altars (RIB 1546) from the Carrawburgh mithraeum.

13 During excavation by Exeter Archaeology in advance of proposed development, directed by Tim Gent. John Pamment Salvatore, Reports Officer of Exeter Archaeology, made it available with details of the excavation.

14 The spacing of line 1 suggests that only two capital letters have been lost to the left, for a ‘heading’ which consisted of a personal name in the dative case. The most likely restoration is [Ve]ro, ‘to Verus’, although other names are possible such as Carus and Varus. In line 2, he would have been described by his rank or occupation, which makes arm[…] an attractive reading, whether for arm[orum custodi], ‘armourer’, or a reference to armamentarium, ‘the armoury’. It may well have been abbreviated. For this possibility compare the stilus-tablet letter from Vindonissa ‘addressed’ […] | armor(um) cus(todi) (Speidel, M.A., Die römischen Schreibtafeln von Vindonissa (1996), 174, No. 38Google Scholar).

15 By metal-detector. Details and photograph from Adam Daubney, the PAS Finds Liaison Officer for Lincolnshire (see further, Britannia 41 (2010), 453, n. 30Google Scholar), in whose catalogue of TOT rings it is No. 66.

16 During excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology (SF 1227), with the other inscribed items already published as Britannia 40 (2009), 336–46, Nos 34–63Google Scholar. The ink text was recognised by Margrethe Felter during cleaning and conservation, and James Gerrard made it available.

17 2, cassius. The tails of ss have been lost, but this looks like the gentilicium Cassius. There is a space to its left in relation to the other lines, which suggests that a one-letter praenomen has been lost.

18 numeratos in 2 was immediately legible, implying a text that referred to money being ‘counted out’, but other words could only be read with the help of infra-red photographs taken by Charles Crowther in the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Oxford. Difficulty was also caused by the ink having run into the horizontal fibres, and some letters being smudged or defective, as indicated by subscript dots. Word-division, of which there is almost no sign in the original, has also been indicated. Not indicated is the gap in each line (after ille and debere in 2 and 3, and within abhinc, ulla and decem in 4, 5 and 6) which, since it is vertically aligned with the saw-cut in the bottom edge, must have respected the binding-cord now lost.

19 Dated 20 October 162 and 1 June 167 respectively (FIRA III, 122 and 120 = IDR I, 35 and 43). The note of a.d. 167 is quoted below in commenting on sine ulla replicatione (5). The relevant portion of the note of a.d. 162 reads: ‘… et se eos (denarios) LX q(ui) s(upra) s(cripti) s(unt) mutuos numeratos accepisse et debere se dixit: et eorum usuras ex hac die … dari f(ide) p(romisit).’ That this was formular is clear from the loan-note quoted by Modestinus in the 230s a.d. (Digest 22.1.41.2) as being typical: ‘scripsi me accepisse et accepi ab illo mutuos et numeratos decem, quos ei reddam kalendis illis proximis cum suis usuris placitis inter nos.’ The only other British example is the Carlisle fragment of 7 November 83 (Britannia 23 (1992), 146–50Google Scholar, where others are cited at 148, n. 33).

20 Line-by-line commentary:

1. Only the first two words survive, but the endings indicate a verb followed by a noun in the masculine nominative case, and only the first letter of each is really in doubt. Tittius is well attested as the name of a samian potter, but also occurs as a gentilicium. It was presumably the name, or part of the name, of the debtor; but unfortunately the context is now lost.

2. adfirmat is the verb which corresponds to dixit and scripsi in the loan-notes already quoted. Its ending is obscured by surface discoloration, and there is what looks like trace of a downstroke leading from the diagonal of a, but there is no further sign of n (for the plural -ant) nor space for it, and the singular -at is confirmed by ille.

numeratos is clear, but the preceding word is unparalleled: mutuos (‘lent’), as in the loan-notes already quoted, cannot be read; nor the references to ‘coin’ found in other loan-notes such as denarios, nummos or the adjective probos (‘sound’). But the word certainly begins with o and ends with -os, and the medial ta is clear enough; so the reading opta[t]os is inevitable. A sense of ‘hoped-for’ money is inappropriate here, but the sense of ‘choice’ (literally ‘chosen’) is quite acceptable. This may refer to a provision now lost — perhaps the debtor ‘chose’ to take his money in a certain form, maybe in gold — but it is more likely to be the equivalent of probos in the sense of coin which was ‘choice’, even selected, as not being worn or clipped, debased or counterfeit.

3. There is what might be a medial point after placet, but since there is none elsewhere, and the verb follows a break in syntax with debere, the mark is probably casual. The impersonal verb placet evidently introduced a new provision, that of repayment, which in some loan-notes is dependent on a personal verb (promisit, debebit, etc.); but the Digest example already quoted also uses placere impersonally in the sense of ‘agreement’.

3–5. The reference to interest being due from the date of the loan is standard, for example in the loan-notes quoted above. But the relevant clause also contains two phrases which are unparalleled, aprili abhinc (4) and sine ulla replicatione (5).

Aprili naturally suggests the month of April, but a month in the dative (or ablative) case is difficult to relate to the infinitive reddi which requires a dative of the recipient; and if Aprili referred to the date of repayment (hardly of the loan itself, since this was 3 December, ex die praesenti), the exact day would surely have been specified, for example kalendis Aprilibus proximis. But Aprilis is also quite a common cognomen, so it may be conjectured that it was the creditor's name, which unfortunately has been lost with the first half of the text. The temporal adverb abhinc is used of the length of time which has elapsed ‘from the present’, almost always in the past (in the sense of ‘ago’); it is difficult to interpret here, but perhaps it redundantly reinforced ex die praesenti.

Gaius (Inst. 4.126) and Ulpian (Digest 44.1.2.2) both describe replicatio as a counter-plea advanced in litigation, but here it is no more specific than the parallel phrase with controversia (‘argument’) which qualifies repayment in the Dacian loan-note of a.d. 167: ‘(denarios) … quos ei reddere deb[e]t sine ulla contraversia [sic].’

5–6. The text ends like many legal documents, including the Dacian loan-notes, with the formula of actum (‘executed’) followed by a place-name in the locative case and the date to the day. This place-name is quite well preserved, but unfortunately it was scrawled and does not suggest any known place. It was presumably in Britain, but even this is uncertain in a document from London. The first letter is apparently l, with the second stroke made separately. It is followed by a, and then by a peculiar rae which nonetheless resembles that in praesenti (5).

21 This format goes back to the Neronian senatusconsultum of a.d. 61 (Suetonius, Nero 17, with Meyer, E.A., Legitimacy and Law in the Roman World (2004), 165–8CrossRefGoogle Scholar), and was embodied in the ‘triptych’ of three stilus writing-tablets bound together. It may further be conjectured that the second tablet of the three, being recessed on both faces and thus potentially the most fragile, had actually broken; and that someone then improvised a legal document from the two remaining tablets, by writing the ‘inner’ text on their waxed faces with a stilus, sealing them face to face, and duplicating this text in ink on the two outside faces which were not recessed for wax.

This conjecture cannot be confirmed from the little that remains of the waxed text, since there is no corresponsion with the inked text. But this is not decisive: the surviving stilus text may duplicate only the lost portion of the ink text; it may even belong to an earlier use of the tablet, whether the wax coating was subsequently smoothed and re-used, or even left blank if the new text was quite short. It also looks as if the surviving traces belong to the first ‘page’ of any text, since there is no sign of the actum formula at the bottom.

22 With the next two items during excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology (Britannia 34 (2003), 345Google Scholar). James Gerrard made them available.

23 The graffito is complete. For another example of this common personal name thus abbreviated, see RIB II.7, 2501.621 (Great Chesterford).

24 The graffito is complete, the initial letter of the owner's name.

25 This is quite a common name, which has already been found in London (RIB II.7, 2501.165 and 166).

26 With the next item during excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology (Britannia 34 (2003), 347Google Scholar). James Gerrard sent photographs and other details.

27 The graffito is evidently complete, and more likely an abbreviated personal name than a numeral (‘6’). In view of the next item, this is likely to have been Victor or a cognate name such as Victorinus, although there are other possibilities such as Virilis and Vitalis.

28 Since the vessels overlap in date, and were found at the same site (it is not explicitly stated that both were found in the same context), it is quite possible that they both relate to the same owner whose name began with VIC. This would strengthen the likelihood of Victor or Victorinus, both very common names.

29 By metal-detector, and recorded by PAS. Sally Worrell sent a photograph and other details.

30 There is no sign of the bottom stroke of the second E, but elsewhere the horizontal strokes are rather slight, and the sequence BEBF would be difficult. The interpretation is conjectural. bibe and pie zeses are both quite frequent slogans on drinking vessels (etc.), but their conflation seems unparalleled. Vulgar confusion between short [i] and [e] is frequent, for bebe < bibe, but confusion must also be assumed in the un-Latin zeses between [s] and [z].

31 The next eight items were found during excavations by the Vindolanda Trust, all in 2010 except for the leather off-cut (No. 19). Robin Birley made them available, and Anthony Birley sent a copy of his detailed report on the two mirror-frames (Nos 17 and 18).

32 The division into two names is conjectural, since *Capictinus is not attested, but there is a small change in direction with the second C, which suggests a break here. The initial sequence suggests Carantus or Carantius, which is frequent in CIL xiii and has already occurred at Vindolanda (Britannia 39 (2008), 384, No. 19Google Scholar). The excavators therefore read IIC as VS, but their putative V is unlike the V before S, and their putative S (which has no tail) resembles the succeeding C. The second stroke of II has a short leftward tail, which might suggest a defective O or S, but is better seen as casual as the stilus was being lifted. Unless II is for E (which is visually attractive but hard to explain), it would conclude Carantii, ‘(the son) of Carantius’, as the patronymic of *Capictinus. This name's closing sequence suggests pecten (‘comb’), which is presumably a coincidence, but there seems to be no closer analogy than Respectinus (see for example M.P. Speidel, Denkmäler No. 620, an eques singularis Augusti from Noricum).

33 The object was identified by Giulia Baratta of the University of Macerata, who provided references with which Anthony Birley wrote his report (see above, n. 31). Fourteen of the maker's cast-lead mirror-frames are known, all from Gallia Narbonensis except one from Xanten, three of them incorporating moulded inscriptions which give his name and place of manufacture as Κύ(ιντος) Λικ(ίνιος) Τουτεινος ἐν Ἀρελάτω(ι) πο(ι)εῖ. The Vindolanda mirror-frame is the first in Latin, and the first to include his praenomen; like the Greek, it uses the present tense (facit).

34 Birley (see above, n. 31) comments that the maker seems to be otherwise unattested, and his name is comparatively rare, so that his workshop cannot be located.

35 There are enough small differences to suggest that the three lines of (i) are by different hands, and thus are individual ‘signatures’.

(i) 2 is the masculine cognomen Martialis, which is understandably popular with soldiers, but has not occurred at Vindolanda before, except possbly in Tab. Vindol. III, 609.b.back 3n.

(i) 3 is the masculine cognomen Super, which occurs at Vindolanda only in correspondence from elsewhere (Curtius Super in Tab. Vindol. II, 213.i.1, and Clodius Super in II, 255.1 (with 255.App.back), III, 629.1, and perhaps II, 334.5). The reading is certain, but confusing since the scribe made the second (down)stroke of P, but then did not lift his stilus as he dragged it to the first downstroke of E.

(i) 1 is more difficult. It is complete, as drawn, and certainly ends in A; so it can hardly be a masculine cognomen like the others. The first letter is apparently A, but in certain hands might be R or even P. The next three letters have a marked leftward extension, unlike L in Martialis, and are most easily read as LL and the beginning of a fourth letter, whether A or M. But T could be read instead of either L, although quite unlike that in Martialis, and AN or ARI or MI variously before the final A. None of these combinations yields an obvious name, so the reading remains uncertain.

36 A is written with a third, detached downstroke. VS is apparently ligatured, with a loop for V, followed by a long diagonal downstroke; another stroke might have been expected to complete S, but either it was not made, or it has been lost in the rough surface at the edge of the off-cut. This masculine cognomen has not occurred before in Britain. Although it is borne by the legionary legate Cornelius Aquinus in a.d. 68 (PIR C 1325 = Tacitus, Hist. 1.7), it occurs mostly in Gaul and Cisalpina.

37 This century is not otherwise attested at Vindolanda.

38 This is not a name-ending: the graffito is complete, and there is a slight but sufficient tail to the first letter, so that R not P should be read. The name Rinus is very rare, but occurs in Spain as a complete graffito, the owner's name in capitals scratched underneath a samian vessel: J.A. Cerdà Mellado et al., El Cardo Maximus de la ciutat romana d' Iluro (Hispania Tarraconensis) (Laietania 10, 2; 1997), 71 with 101, fig. 114 (noted as Hispania Epigraphica 7 (1997), 246Google Scholar).

39 The graffito is complete, but the dotted letters are too angular to be certain: the first is presumably C, but might be P or S (without a tail) or even O (by including the next letter); the second might be L, but its angles suggest C again; and the third is apparently a square but incomplete O. *Micico is not attested, but may be a variant of Miccio, which is well attested as a samian potter's name (etc.).

40 The excavators read MITACIVS, but the first three strokes are linked (thus N) but separate from the fourth, which itself is parallel with the fifth (and thus II for E). The name is apparently not attested.

41 During excavation by Absolute Archaeology. Naomi Payne, Historic Environment Officer (Archaeology) of Somerset Heritage Centre, sent a photograph and details.

42 The letters are of different heights, and the loops of B rather faint. The letters are not aligned with the base, and B abuts the right-hand edge, so they may have been cut before the stone was shaped. They certainly do not relate to the weight (which is technically 8.84 librae), but they may indicate the owner's name.

43 Excavated by the University of Winchester, directed by Tony King. James Gerrard of Pre-Construct Archaeology made the sherd available.

44 A with its extended second stroke is ‘cursive’ in form. The tail of C has broken out at the edge of the sherd, but the letter does not appear to be G. The beginning of a personal name; possibly Acceptus or Acutus, but there are other (less common) possibilities.

45 With the next two items during excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology (Britannia 39 (2008), 328Google Scholar). Two samian sherds were also found scratched with two intersecting lines, a ‘cross’ for identification. James Gerrard made them all available.

46 The graffito is complete. The tail of C continues downwards at a diagonal, which might suggest G, but its closeness to the next letter, and the form of both, make it more likely that this stroke is either a slip of the stilus due to a flaw in the surface (drawn in outline) or the cross-stroke of A. The first stroke of A was cut twice. Like the next item, which it resembles although the letters do not have quite the same form, this is an abbreviated personal name with many possibilities, including Candidus and Carus. Both vessels may well have belonged to the same person.

47 Only the tip survives of the first letter, which might also be G, S or V, but C looks more likely. If the graffito was centred, as also seems likely, it was the first letter. An abbreviated personal name like the previous item, and quite likely the same one.

48 The name is quite common, and sometimes abbreviated to IAN.

49 With the next three items during excavations directed by N. Hodgson, for which see Arbeia Journal 6–7 for 1997–8 (2001), 25–36Google ScholarPubMed. Alex Croom sent full details including casts and photographs.

50 Obverse and reverse are from the same dies as RIB II.1, 2411.103 and Britannia 38 (2007), 363, Nos 31 and 32Google Scholar.

51 The obverse is not from the same die as the preceding item, nor from that of RIB II.1, 2411.103.

52 Two others were also found, IM 136 unstratified, and IM 142 in a later third-century context between Granaries C11 and C12.

53 IM 127 is A[…]; IM 143 AV[…]; IM 128 and 129 […]GG; IM 130 […]GG[…]. Thus they belong to the same group as RIB II.1, 2411.1–15, and depict Septimius Severus and his two sons, before Geta formally became Augustus.

54 Noted by Hodgson (see above, n. 49), 30 n. 6, who comments that it is the first instance of AVGGG on a sealing from South Shields.

55 During excavation by Cardiff University and University College, London, directed by Peter Guest and Andrew Gardner for Cadw and the Roman Legionary Museum, Caerleon (see Britannia 40 (2009), 222Google Scholar). The conservator, Megan de Silva, sent a comprehensive range of photographs. A centurial stone was also found (ibid., 314, No. 2).

56 The angular script resembles that of a waxed stilus tablet, not an ink text. Thus E is made with two vertical strokes (II), curves tend to be reduced to several short strokes (see O, R and S); exceptionally, R is cursive in 1 and 4, but capital-letter in 2.

57 Line by line commentary:

1. The centurion Domitius Maternus is not otherwise attested in Britain. He is possibly to be identifed with the centurion C. Domitius Maternus of the Egyptian legion II Traiana, the only centurion discharged with veterans of the legion at Nicopolis in a.d. 157, after they entered service in a.d. 132/33 (AE 1955, 238). His rank as centurion is confirmed by AE 1969/70, 633, V. His origin is noted as Seleuco, presumably Mons Seleucus in Gallia Narbonensis, but although he may well have served in a western legion like II Augusta, the chronology of identification is tight. See note to the next line.

2. The legionary Aurelius Severus is not otherwise attested at Caerleon. His gentilicium requires that he or his father (etc.) was enfranchised in the reign of Antoninus Pius (a.d. 138–161) or later, with the complication that after a.d. 140 auxiliary veterans did not gain citizenship for their existing children. Thus Severus would not have been old enough to serve under a centurion discharged in a.d. 157 in Egypt, even if the latter had previously served in Britain, unless his own father was actually discharged within the period a.d. 138–140 and thus gained citizenship as an Aurelius for his adolescent son. Another possibility is that Severus himself was granted citizenship on enlisting in the legion, a practice attested in provinces such as Egypt where Roman citizens were in short supply.

3, lev(i)gatam. Severus' property, to which this tag was attached, was evidently feminine in gender. Possibly it was his military tunic (tunica militaris), which is associated with levisata [sic] in glosses quoted by TLL VII.2, 1224, 15ff. s.v. levisata. If so, lev(i)gatam would mean ‘polished’, in the sense of finishing clothes: compare Gaius, Inst. 3.143 = Ulpian, Dig. 47.2.12, ‘fulloni … polienda vestimenta’. For the process of fulling, and its association with lead tickets, see Römer-Martijnse, E., Römerzeitliche Bleietiketten aus Kalsdorf, Steiermark (1990), esp. 235ffGoogle Scholar.

4. pingatarem. There is some damage due to folding, but the reading seems good. Although the penultimate letter is undoubtedly E, not A, and the word is apparently adjectival in form, not a past-participle passive like lev(i)gatam, it surely described another process to which Severus' property was subjected. Unfortunately *pingitarem is not attested, but perhaps it was developed from pingo in the sense of ‘stitching’ or ‘darning’ (compare Pliny, Hist. Nat. 8.191, ‘lana … ex qua vestis detrita usu pingitur’, ‘wool used to darn worn clothes’). A reference to ‘embroidery’ (also a sense borne by pingo) seems unlikely here.

On this interpretation, the tag would be the Roman equivalent of a laundry label, identifying the owner of the garment attached, and what was to be done to it. A note of caution must be sounded, however, since craftsmen in a legionary workshop (fabrica) might include lamnae levisatares (ChLA x 409); the editors cite TLL (as above), but suggest that they were polishing the iron plates of lorica segmentata. If so, it might be argued that it was Severus' armour, not his tunic, which was being ‘polished’ and (perhaps) ‘decorated’.

58 Georgina Plowright sent copies of the dated drawings, now in Northumberland County Record Office. The date is not necessarily that of discovery, since in October 1843 Bell also drew the lower part of RIB 1455 (already known in 1801) but not the upper part (first recognised or found after 1840), and RIB 1464 (found before 1840).

59 Society of Antiquaries Minute Book vii, f. 196, a transcript of which from Adrian James was sent by Robert Janiszewski (see next note) with the reference to Archaeologia 2 (1773), 41 with pl. III, fig. 4. This drawing (fig. 27 above) shows that the two inscriptions were not on the ‘obverse’ and ‘reverse’ (RIB), but at either end.

60 Pennant, T., A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772 (ed. Simmons, Andrew, 1998), 90Google Scholar. Davidson, as Pennant implies by equating 8 drams with half an ounce, reckoned by avoirdupois weight, in which there are 16 drams (each of 27.33 grains) to the ounce [28.375 grams]. The discrepancy between Pennant's note of weight and that in RIB was noticed by Robert Janiszewski of Warsaw University, who is studying the punched-dot graffito on a similar gold ornament found at New Grange, Ireland, which reads SCBONS ° MB.

61 MB also concludes the New Grange graffito (see previous note). The sequence of a horizontal line followed by three verticals occurs as part of the notes of weight on the Corbridge lanx (RIB II.2, 2414.38) and the Proiecta casket (Shelton, K.J., The Esquiline Treasure (1981), 72Google Scholar, fig. 17), and evidently means ‘3 (ounces)’. The punched dots on the flat end itself, probably forming a circle rather than a semicircle as drawn, must have been decorative rather than part of the annotation, since they occur on both ends.

62 See Warry, P., ‘Legionary tile production in Britain’, Britannia 41 (2010), 127–47, at 128, n. 6CrossRefGoogle Scholar. He coins the reference RIB II.4, 2460.96 for the new die.

63 See Swan, V.G. and Philpott, R.A., ‘Legio XX VV and tile production at Tarbock, Merseyside’, Britannia 31 (2000), 55–67, at 60–1CrossRefGoogle Scholar, with fig. 1. RIB II.4, 2463.46, which shares the same distinctive ansa, should be read inverted as LXX[…].

64 The medial points do not appear consistently in all examples, no doubt because the die became clogged. Swan and Philpott (see previous note) read VI (not V) at the end by analogy with the beginning, where the vertical of L also serves to complete the triangular ansa. They reject any expansion of VI to Vi(ctoriniana), and suggest that it refers to the contractor. See further, next note.

65 By Warry (see above, n. 62), at 137, n. 36, with fig. 6. Like RIB II.4, 2463.56(vi), it was found in Hunter Street, Chester. Warry demonstrates its second-century date, which means that RIB's tentative expansion of V to V(ictoriniana) should now be abandoned. He follows Swan and Philpott (see above, n. 63) in referring it to the contractor Vidu(…) (see below, n. 67), and suggests that DE (RIB II.4, 2463. 54 and 55) and LOGOPR (ibid., 58) also refer to contractors. This seems very likely.

66 By Swan and Philpott (see above, n. 63). Their fig. 1c (p. 57) supersedes the composite drawing in RIB, which restores [C F] and [X V V] on the right.

67 Exceptionally the legion does not bear its abbreviated cognomina V(aleria) V(ictrix). The expansion of the legend is uncertain. TEGVLA is apparently tegula (nominative, ‘tile of’), but tegula(m) (accusative, ‘tile made by’, understanding fecit) or even tegula(ria) (‘tilery of’) are possible. Swan and Philpott (see above, n. 63), 58–9, prefer tegula(ria), by analogy with tiles stamped by tegula(ria) transrhenana across the Rhine (CIL xiii 12528 E), but some tileries at Rome certainly refer to tegula (‘tile’, nominative) by distinguishing in their stamps (CIL xv 650, 651, 2232, 2233) between TEG / TEGLA and FIG, fig(lina) (‘tilery’). Swan and Philpott, supported by Warry (see above, n. 62), also improve on RIB by seeing A VIDV as the name of a contractor; from which it follows that LEG is dative, leg(ioni), ‘for the Legion’. They accept the expansion of A VIDV to A(ulus) Vidu(cus) or A(ulus) Vidu(cius), but this too is open to question. By the second century, a Roman citizen is most unlikely to have borne only two names: instead of a praenomen (Aulus), which by now was often omitted, A is likely to be an abbreviated nomen. The ‘imperial’ nomina A(elius) and A(urelius) spring to mind, but this depends on whether VERO III COS refers to the third consulship of Annius Verus (a.d. 126), as in another tile-stamp from Rome (CIL xv 277), or that of Lucius Verus (a.d. 167). Although RIB accepts the latter, the earlier date of a.d. 126 was justifiably asserted by Salomies in AE 2000, 831(b), and should be preferred as more in keeping with other evidence (thus Warry (see above, n. 62), 138). A(urelius) is thus excluded, but A(elius) is perfectly possible.

68 Unpublished, but see now Weston, D.W.V., Carlisle Cathedral History (2000), 95Google Scholar.

69 Martindale, J.H., ‘Notes on the remains of the conventual buildings of the Augustinian priory, Carlisle, now the cathedral’, Cumb. Westm. 2nd ser. 24 (1924), 1–16, at 16Google Scholar. The reference was communicated by Canon Weston to Ian Caruana, who sent this information.

70 By courtesy of Leeds University, after it was located by Elizabeth Hartley. It is now stored with RIB III, 3215 (also Brough-by-Bainbridge), in the Parkinson Building, Store B08.

71 After examination in Manchester Museum by courtesy of Bryan Sitch, Deputy Head of Collections. The back is not accessible, nor is the base, since its missing back has required the altar to be set into a platform to keep it upright.

72 1–4 are close-spaced vertically, 5–7 slightly more open. Letter heights: 1, 40 mm; 2, 30 mm increasing to 38 mm; 3 and 4, averaging 35 mm; 5 and 6, 40 mm; 7, c. 42 mm.

73 As already noted, this is the first British instance of the Matres Hananeftae, who are attested in Lower Germany at Cologne (CIL xiii 8219, Matribus Paternis Hiannanef(…)) and Wissen (CIL xiii 8629, Matribus Annaneptis), both dedicated by officers of the Thirtieth Legion Ulpia Victrix. The Matres Ollototae, although of similar ‘overseas’ origin (compare RIB 1030, Matribus Ollototis sive Transmarinis), are attested only in Britain, at Heronbridge near Chester (RIB 574) and at Binchester (RIB 1030, 1031 and 1032).

74 Information from Georgina Plowright.

75 See above, Addenda et Corrigenda (h), with n. 70.

76 Information from the Curator, Lisa Webb.

77 In the rockery of a modern garden by the owner, Trudi Deane, who sent photographs and dimensions. Information also from Katie Hinds, Wiltshire Finds Liaison Officer, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum. The inscription, which is apparently unpublished, is presumably a ‘Grand Tour import’ most likely from Greece or Asia Minor, but its recent provenance is unknown.

78 Figured on some websites as if genuine. Alex Croom confirms that it is one of several made by the volunteer stonemason at Arbeia.