No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

III. Inscriptions1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 August 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2016

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s) 2017. Published by The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Footnotes

No inscriptions on STONE have been reported this year, but RIB 2153 has been rediscovered: see below, Change of Location (b). Previous discoveries are cited by item, not page-number, in R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), as RIB (1–2400) and RIB III (3001–3550). Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

References

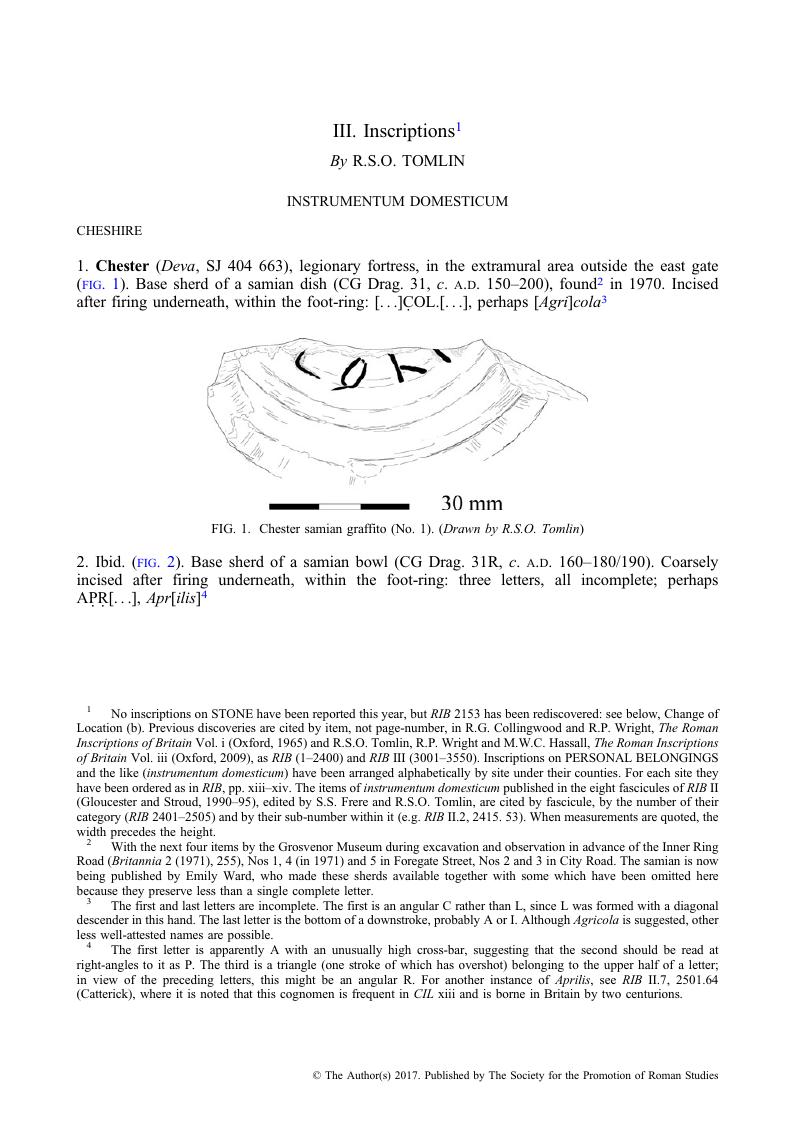

2 With the next four items by the Grosvenor Museum during excavation and observation in advance of the Inner Ring Road (Britannia 2 (1971), 255Google Scholar), Nos 1, 4 (in 1971) and 5 in Foregate Street, Nos 2 and 3 in City Road. The samian is now being published by Emily Ward, who made these sherds available together with some which have been omitted here because they preserve less than a single complete letter.

3 The first and last letters are incomplete. The first is an angular C rather than L, since L was formed with a diagonal descender in this hand. The last letter is the bottom of a downstroke, probably A or I. Although Agricola is suggested, other less well-attested names are possible.

4 The first letter is apparently A with an unusually high cross-bar, suggesting that the second should be read at right-angles to it as P. The third is a triangle (one stroke of which has overshot) belonging to the upper half of a letter; in view of the preceding letters, this might be an angular R. For another instance of Aprilis, see RIB II.7, 2501.64 (Catterick), where it is noted that this cognomen is frequent in CIL xiii and is borne in Britain by two centurions.

5 There is just enough space to the right to suggest that the graffito is complete, although this is not certain. Since the numeral ‘51’ is unlikely, this would be an abbreviated personal name. The possibilities include Liberalis, which is quite common and should probably be restored in RIB 533 (Chester), Iul(ius) Lib[eralis].

6 Perhaps a personal name ending in -osus, but the third letter might be A.

7 During excavation directed by Haynes, Ian and Wilmott, Tony (Britannia 47 (2016), 303–4)Google Scholar. Ian Haynes made it available, with comments by Brenda Dickinson.

8 The first three letters closely resemble the retrograde signature of the mould-maker Catullus, as Brenda Dickinson has noticed; she provided a rubbing of it on the wall of another Drag. 37 bowl. In the Maryport graffito the fourth letter, which resembles L reversed, can be taken as V. But the fifth letter is more like C than L, and is apparently followed by a long downstroke as if for a genitive termination; however, it may be followed by trace of further letters.

9 By a metal-detectorist (PAS ref.: DUR-C3E4FE) and reported to Ellie Cox, who was then finds liaison officer for Durham. She made it available after it had been studied first by John Pearce, in collaboration with whom full publication is intended after cleaning and conservation, now that it has been acquired from the finder by the Museum of Archaeology, Durham.

10 He is the second Briton, after Aemilius Saeni f(ilius) (AE 1956, 249), known to have served in the German Fleet. The details, notably the elaborate Celtic names of the recipient and his father, the previously unknown fleet-commander, and the date of issue including a new pair of suffect consuls, must await full publication, since they depend on close reading of damaged areas not yet cleaned and conserved.

11 By a metal-detectorist (PAS ref.: ESS-5945F8). Like other Portable Antiquities noted here for their inscriptions, it was communicated by Sally Worrell.

12 The fragment closely resembles the Rudge Cup (RIB II.2, 2415.53) and other copper-alloy pans naming forts from the western end of Hadrian's Wall: see D.J. Breeze, L. Allason-Jones and P.A. Holder, The First Souvenirs: Enamelled Vessels from Hadrian's Wall (2012). The forts are Stanwix and Castlesteads, but the exact transcription of their names varies.

13 By Colchester Archaeological Trust. Philip Crummy sent details and a photograph.

14 Alternatively it is part of a column c. 1 m in diameter, with the inscription running vertically like RIB III, 3089 (Caerleon), a pillar with a centurial inscription; but in view of where it was found, this is less likely.

15 If these are indeed numerals, what they measured is quite unclear. Three coping-stones from the Chester amphitheatre (RIB III, 3154, 3157 and 3158) are informally inscribed, but this was to record building-work or seat-reservation.

16 During the excavation published in A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines: Excavation of a Ritual Complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire: 1977–9 (1993), in which it is noted on p. 128 as no. 24 (sf 809b). It will be published with fuller commentary in the final report being prepared on the inscribed lead tablets.

17 Note to the outer text:

[d]evo Marti is repeated as a heading by the inner text, which confirms the reading. It is apparently followed by VS, assuming that V incorporates the I of MARTI, which suggests the formula v(otum) s(olvit). The writer omits his name, since the next word is the dative propitio (the second p being cursive), which is occasionally found as the attribute of a god, for example Mercury in CIL xii 2440. It occurs once in Britain, also as an attribute of Mercury: RIB 244 (Leicester), Merc[ur(io)] prop(itio).

18 Notes to the inner text, line by line:

1. devo Marti is repeated from the outer face. For devo instead of deo, compare RIB 306 (Lydney Park), devo Nodenti, which like divo Mercurio in Uley No. 9 (sf 92) probably reflects the Celtic word for ‘god’, deivos (variously spelt), unless the medial u is a ‘glide’ between the e and o. Next came the petitioner's name, but this is largely lost and beyond restoration.

2. quaeritur is a ‘hypercorrection’ of queritur, which should also be read in Uley No. 43, 2 (Britannia 20 (1989), 329, no. 3Google Scholar); compare Tab. Sulis 54.1, conq[u]aer[or].

2. si ser(v)us si liber. This formula is frequent (Tab. Sulis, p. 67), and so is the ‘Vulgarism’ serus for ser(v)us. Continuity of sense with the next line suggests that liber is the last word of line 2, and that little has been lost of the top right-hand corner.

3. vas apium (literally, ‘container of bees’). Columella uses alvus / alveare for ‘beehive’, but refers to it as vas: for example Res Rustica 9.11.1, ‘cum primo vere in eo vase nata est pullities’ (‘when in spring a brood is born in that vessel’), whence OLD defines vas as (1.b) ‘applied to other forms of container; esp. to beehives’. The Lex Salica, an early sixth-century German law code, uses vas as a synonym for ‘hive’ when imposing monetary penalties for the theft of beehives: tit. viii (de furtis apium), 1. ‘si quis unam apem de intro clavem furaverit … 2. si quis unum vasum … furaverit’ (‘Concerning the theft of bees: if anyone steals one swarm (apem) under lock and key … if anyone steals one hive (vasum)’). Domesday Book likewise uses vasa apium when enumerating beehives in East Anglia. This tablet is thus the first documentary evidence of beekeeping in Roman Britain, which is implied by Tab. Vindol. III, 591, b.2 and 10, a list of ?medical supplies which include ‘wax’ (cera) and ‘linen soaked in honey(?)’ (lini mellari).

3. invalauit is a sub-standard spelling of involavit also found in Uley No. 80, 4 (Britannia 27 (1996), 439, no. 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar), suggesting that [in]valaverint should be restored in Britannia 15 (1984), 339, no. 7Google Scholar (Pagans Hill). The end of the line is damaged, and the restoration (of an adverb?) is uncertain. It is also difficult to align the detached fragment with the rest of the tablet, but si ipsum at the end of line 6 naturally leads to vas at the beginning of 7.

4 begins apparently with a conditional clause which qualifies the ne permittatur curse which follows, but although COMODIA is quite well preserved, there is no evidence of a word *comodia. But the form com[o] for quomodo is found in Tab. Sulis 4.2, which might suggest a bungled clause to the effect of quocumque modo erat, ‘in whatever way it actually happened’ (referring to the theft or removal of the beehive).

4–6. ne illi permittatur (etc.) are frequent formulas (Tab. Sulis, pp. 65–6), but have been carelessly transcribed here: nec was written twice, ca was omitted from manducare, and the final m is missing from sanitatem (this is a frequent ‘Vulgarism’, but not found in somnum). The infinitive required by somnum and sanitate(m), presumably habere, was also omitted.

6. nesi is a variant of nisi also found in the Eccles curse (Britannia 17 (1986), 431, no. 2Google Scholar); compare Tab. Sulis 65.10, nessi. somnum is carelessly written as if semnum, o being reduced to a loop, as in Tab. Sulis 35.6. c(o)ngortiam in 8 offers a still more extreme example of this letter-form.

7. ad locum suum reversetur. Usually it is the god's temple to which the stolen property is to be returned (Tab. Sulis, p. 68), but for another instance of ‘place’, see Tab. Sulis 64, nisi eidem loco ipsum pallium [re]ducat (‘unless he return the said cloak to the same place’). But the impersonal construction with a passive verb is most unusual: pertulerit might have been expected, the subject being the thief. This is the first British instance of the rare verb reversare, which is only found in Late Latin and should mean ‘turn round’; perhaps it was confused here with revertere (‘revert’).

8. c(o)ngortiam. The first o is written just like e, as in somnum (6) above. This idiosyncratic form of concordiam, with c voiced to g and d confused with t, is also found in Uley No. 57, but they are written by different persons. The formula is related to that in Uley No. 72 (Britannia (1992), 310, no. 5Google Scholar), et meam concordiam habuerit (‘and shall have my goodwill’), but there the concordia is the writer's, not the god's. In the present tablet, the god has now become ‘Mercury’, although he was first addressed as ‘Mars’; two other Uley tablets (Nos 3 and 8) are addressed to both gods together, Marti Mercurio.

8. agat. The reading is not certain, since only the angle of g survives, and it is difficult to align the detached fragment, but sense would suggest that the subject is the thief. In strict syntax, however, after the passive reversetur, the subject would be vas, as if the stolen object, by being returned, would reconcile the god with the thief.

9–11. Except for isolated words, the rest of the text cannot be read because of the crowding of the letters as space ran out, the loss to the edges, and other damage. If pariat (10) be read, its p is quite unlike that in previous lines.

19 PAS ref.: B9A082. Wendy Scott, finds liaison officer, took more photographs and sent them.

20 The dotted letters are incomplete: C might be read instead of G, and I instead of E. Since the lettering is a little irregular and would have been upside-down when the spoon was being used, it was probably inscribed by the owner himself, holding the spoon in his left hand, rather than professionally in a workshop. His name, which combines the Celtic elements *tegernos and *maglos (both meaning ‘king’ or ‘lord’; see A. Holder, Alt-celtischer Sprachschatz s.v.), is well attested in the post-Roman period, notably by a tombstone in Cornwall (IBCh 12), Conetoci fili(i) Tegernomali. The spelling varies between Tigern- and Tegern-, which should properly be followed by o, not e; the case was either nominative (as restored) or genitive (-magli), but -maglus was probably not reduced to -malus by lenition. The name is still Tigernmaglus in the ninth-century Life of Paul Aurelien, a form thought to reflect sixth-century Welsh tradition (K.H. Jackson, Language and History in Early Britain (1953), 46).

21 PAS ref.: LIN-B7B53E, recorded in 2015 (Daubney 96).

22 O is formed by a large central dot within a concentric circle; both Ts bifurcate at the bottom like the Horncastle TOT ring illustrated as Britannia 45 (2014), 444, no. 18Google Scholar.

23 PAS ref.: LIN-424C19.

24 O is formed by a central dot and a concentric circle, very worn; both Ts are completely worn away.

25 PAS ref.: LIN-DE5E24.

26 O is twice the height of T and is formed by a central dot and two concentric circles. There are decorative motifs above and below.

27 PAS ref.: LIN-24B926. For another ‘TOT’ ring from Wellingore, see Britannia 45 (2014), 444, no. 21Google Scholar.

28 During excavation like the next five items, but closer dating and provenance are not always recorded. They were identified as graffiti not in RIB II by Frances McIntosh, who made them available. Except for No. 20, they were all made after firing.

29 It would be usual for the master's name (in the genitive) to follow that of the slave, but NICO, its case unstated, would be an extreme abbreviation for (servus) Nico(…): Attici, explicitly genitive, surely identifies the owner of Nico(…), not the dish. Nico(…) is an abbreviated name of Greek origin, such as Nicomachus, which is more likely than Atticus to be a slave's name. Atticus and its cognates, as Alföldy notes (Epigraphische Studien 4 (1967), 10)Google Scholar, are tyical of Gallia Belgica and Upper Germany; they are well attested in Britain, and for Corbridge see RIB II.7, 2501.74, ΛTT[…]. Below NI is a ‘cross’ made by two much finer lines intersecting, a mark of identification which may be unrelated.

30 C is angular and rather slight, perhaps because it met a flaw in the fabric (drawn in outline). SC is still more peculiar, being a composite formed by a double downstroke and two diagonals. But the reading of the other letters (RII and ENS) is certain, despite E first being made as II, and then as E. Since Crescens is a common name already found at Corbridge as CRIIS (RIB II.7, 2501.146), there is no reason to doubt that this is what the scribe intended. It may be added that there is no instance of recens being a personal name.

31 There is a space after the closely packed letters CΛRT, suggesting they are an abbreviated name, especially since the next letter (two incomplete strokes meeting at an angle) can be restored as an angular S; a diminutive O or a ‘stop’ to indicate abbreviation are possible, but seem unlikely. The abbreviation CART was apparently shared by the dedicator of RIB 1032 (Binchester, now lost), whose name is transcribed by Camden as CART * OVAL. There are two possible nomina, Cartilius and Cartorius, both well attested. Alternatively this is an abbreviated Celtic name incorporating the first element in Cartimandua, followed by the father's name or another form of identification such as signifer.

32 The potter's name, whether or not followed by fecit (‘made (this)’) or similar. Only the first stroke of L survives, but it is elongated downwards, with the hint of a space before the next letter to accommodate its rightward curve. The next letter might also be L, but Helenus is quite a common name, more common than names in Hell…

33 The letters are capitals except for R, which is cursive, its second, curving stroke now faint and incomplete. The name Victor is common, but so is Victorinus, and there are some other derivatives; compare RIB II.7, 2501.608 (also Corbridge, but on samian), VICT[…]

34 With the next nineteen items during excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley; all found in 2016 unless stated otherwise. Barbara Birley made them available and provided details. Unless stated otherwise, graffiti were made after firing. Except for No. 32, acephalous graffiti of fewer than three letters have been omitted.

35 Members of the same family, or perhaps freedmen manumitted by the same master. Two other Vindolanda brands, INGENVIMATER and AELCB, are similarly composed of two cognomina (Vindolanda Research Reports II (1993), 76, A.1 and 82, C.1Google Scholar).

36 Part of the potter's signature, which resembles the second line of RIB II.6, 2493.6, ending in SIIP LVC. This is a date before the Kalends of Sep(tember) in the consulship of Luc[…], suggesting that No. 24 may be a date in the same consulship; but although the first word clearly ends in L, it is not easy to fit the preceding traces to the abbreviated month of April(es) or Iul(ias).

37 Numerals indicating capacity in modii (and sextarii) are often incised after firing on the rim or handle of Dressel 20, and usually range between 7 and 8 modii (RIB II.6, p. 33).

38 For this slogan painted in white barbotine on a Rhenish beaker, see RIB II.6, 2498.32 (with note).

39 The first letter of the owner's name.

40 In view of the space available before the rim was reached, quite a short name; possibilities include Suavis, Super and Surus.

41 II is cut by a diagonal stroke, apparently casual, unless it belongs to another (lost) graffito. There is the tip of a downstroke in the broken edge. The sequence of letters does not suggest any name, unless the scribe inadvertently barred the wrong pair of downstrokes and intended Thel.[…]

42 R is of cursive form. This personal name of Greek origin, variously Marcio and Marcion, is quite common, but this is its first occurrence in Britain.

43 The graffito is complete. The owner's name abbreviated to its first letter.

44 The end of the graffito, and perhaps complete in itself; but more likely to be the owner's name abbreviated to three letters, for example MAT, NAT, PAT and VIT.

45 Damaged, and too incomplete to be legible. Names in Unt[…] and Int[…] are almost unknown.

46 Each downward stroke ends in a leftward flick. The letter is off-centre, but unless (?two) others were widely spaced, the graffito is complete, the scribe having rested his hand on the base to cut so firmly. The initial letter of his name.

47 The horizontal stroke of L is rather faint, and there is no sign of the horizontal stroke of T; the two strokes of II are not parallel because the scribe had to follow the curve of the circumference. But the cognomen Laetus is common enough for it to be read here, in the feminine form.

48 The first letter is difficult to distinguish from a ‘cross’ below the graffiti, which is presumably a mark of identification, but it might be the very end of M. In which case, the unique German name Maduhus (RIB 1526, Carrawburgh) would be possible.

49 A personal name, probably Greek in origin. Nicanor would be possible (compare RIB 970, Netherby, and RIB II.8, 2503.357, Colchester).

50 The first letter looks more like S without a full tail than an angular C.

51 The graffito is complete, but on top of the everted rim is part of another; a single diagonal stroke, […]I, perhaps the end of a numeral.

52 The gap in the middle indicates that there were two words, the first ending in I. This would suggest a nomen in the genitive case followed by a cognomen beginning with OP, the owner's name. The first surviving letter is clearly S, and the space between the second and third letters, together with the difference in their bottom serifs, suggests that they are not II, but TI. The letter after P has the same serif as this putative T, and the cognomen Optatus is quite common. Note also the stilus tablet illustrated in Vindolanda Research Reports II (1993), pl. XXIIGoogle Scholar (with Tab. Vindol. II, p. 365). It is headed by the place-name Vindoland(a)e in the locative case, above two personal names in the dative or ablative case, Cocceio Vegeto and (below it) Sestio Optato. Since this is a recessed tablet with a central groove intended for the seals of witnesses, it is not necessarily the outer tablet of a letter addressed to Cocceius Vegetus from Sestius Optatus, or even to them both as joint recipients. It might instead be the beginning of a list of witnesses who signed ‘at Vindolanda’, although the genitive case would be usual. At all events, it seems quite likely that there was a man at Vindolanda called Sestius Optatus.

53 PAS ref.: BUC-2EF079. The Buckinghamshire finds liaison officer, Arwen James, sent twenty photographs taken from different angles.

54 The ring and its inscription both closely resemble RIB II.3, 2422.51: see below, Addendum (c). M is centred and fills much of the panel, reducing the space available for the other letters. To the left of M, D looks rather like reversed C, but its vertical stroke coincides with the edge of the panel and part of it is visible. Likewise to the right of M, the vertical stroke of E coincides with the edge of the panel, and its horizontal strokes extend further to the right. E was added because, if the dedication had been simply DM, it would not have been possible to distinguish between Mars, Mercury or Minerva. For other finger-rings dedicated to Mercury (as MER), see RIB II.3, 2422.20, 29 and 30.

55 PAS ref.: SOM-653D1E.

56 The abbreviated name of the owner: perhaps Antonius or a derived name, but there are other possibilities such as Antigonus (RIB 160, Bath).

57 By a metal-detectorist (PAS ref.: SOM-23F798) and auctioned by Bonhams (London), in their sale of antiquities on 30 November 2016, Lot 73.

58 Lucius Verus (who died in a.d. 169) took the title Armeniacus in a.d. 163, but Marcus Aurelius only assumed it in 164. Another such ingot was found in c. 1530, but is now lost (RIB II.1, 2404.20), and two fragments in c. 1874 (ibid., 21 and 22).

59 With the next item during excavation by Oxford Archaeology East (Britannia 47 (2016), 332–3Google Scholar) directed by Graeme Clarke, who made the sherds available (sf 445 and 444 respectively) and provided details. They are discussed more fully in the final report.

60 The graffito has been drawn as if vertical (fig. 35), thus resembling a Chi-Rho or even a phallus, but is actually horizontal with regard to the vessel. Its two intersecting diagonals are too acute for Chi (X), but are easily understood as two strokes of a ‘star’, the third of which was extended rightward into the letter B (the owner's name reduced to its initial). B should not be seen as the head of a Chi-Rho, since this would have been a single loop to the right or (occasionally) to the left.

61 A mark of identification like other ‘crosses’ and ‘stars’, probably without religious significance: this question is discussed in the final report, which notes that although the swastika motif is quite often associated with religious dedications, it is also quite often purely decorative. If intended to be votive, it would surely have been made visible, rather than located under the base like an ownership graffito. A covert Christian symbol seems unlikely.

62 During fieldwalking or in ploughsoil during excavation by Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group (HAARG), except for three found in sealed deposits of demolition debris. Kevin and Lynn Cornwell sent photographs, drawings and other details. They will be fully published in the site report.

63 Kitchenham Farm Type 1, the next five items being Types 2–6 respectively. No. 48 (fig. 38) is Type 2, but No. 53 (fig. 39) has no Type number (only Stamp ID 20, 27 and 29). The fabric is Peacock 1 except Type 6, which is Peacock 2 (Britannia 8 (1977), 235–48CrossRefGoogle Scholar).

64 Like the previous items, by Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group. Kevin and Lynn Cornwell sent photographs and other details. Also found was the base sherd of another indented beaker incised underneath after firing with a ‘cross’ (X), a mark of identification.

65 The owner's name, with many possibilities. Both letters are eccentrically formed with the first (vertical) stroke being extended. H is thus ‘lower-case’, and the horizontal strokes of E are set too low, the middle one wavering.

66 During excavation directed by Phil Andrews of Wessex Archaeology (Britannia 42 (2011), 387Google Scholar), who notes the bricks in ARA: The Bulletin of the Association of Roman Archaeology 23 (2015–16), 31Google Scholar.

67 Peter Warry identifies the first stamp as RIB II.5, 2489.21H, but the second (fig. 40) as new, in view of the differences in spacing and letter-form. L H S is attributed to the tilery at Minety (Wilts.).

68 By a metal-detectorist (PAS ref.: YORYM-20B68C). Cf. Pearce, J. and Worrell, S., ‘Roman Britain in 2016. II. Finds reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme’, Britannia 48 (2017), no. 4Google Scholar.

69 L and I were not separated by a space, so they were inadvertently treated as one letter and both filled with red enamel.

70 During the building of the present railway station, since it was presented to the Yorkshire Museum by the Directors of the N.E. Railway in 1872, as noted in A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities in the grounds and in the Museum of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society (8th edn, revised by J. Raine, 1891), 124. That it was inscribed was noticed by Adam Parker, who sent photographs of both faces.

71 The second letter might be I, were it not accompanied by a short diagonal stroke, detached but appropriate to L. There is also some abrasion, but no other certain letter. The inscription is perhaps a personal name beginning Fl… (most likely the nomen Flavius or a derived cognomen), which was left unfinished. The two holes were pierced from opposing faces, indicating that the tag had already been folded in half; it follows that the inscription on the inner face was no longer visible, which suggests that it was unrelated to the purpose of the tag, which however is unknown. In spite of being gold, the tag is not a magical lamella like RIB 706, which was found in the same cemetery in 1839–40. Raine (see previous note) comments that ‘a similar plate was discovered a few years since in a marble tomb at Athens, which had been fixed in a head-dress as an ornament’.

72 After the formal excavation by Hartley, Brian (Britannia 1 (1970), 281)Google Scholar, when the Huddersfield and District Archaeological Society was recording a Flavio-Trajanic cemetery north of the fort revealed by construction-work on the M62. The sherds probably belong to subsequent occupation here in the period c. a.d. 120–40. Nick Hodgson made them available and provided full details.

73 The potter's signature. It somewhat resembles Philerus in RIB II.6, 2493.44 (Catterick), but the individual letter-forms are different and so is the reading. Above the name Helenus is apparently the tail of a letter, probably S, although the incision is more shallow and less sharp than the lettering of Helenus, so it may only be casual. But on Dressel 20, the potter's name is sometimes written below a date, which would incorporate a month ending in -s. Helenus is well attested as a personal name, but seems to be previously unrecorded on Dressel 20, unless it lies behind the dated signature from Monte Testaccio which Dressel read as V K IA[…] | HIILI (CIL xv 3605).

74 During the excavation noted in Britannia 23 (1992), 307–8Google Scholar, like Britannia 41 (2010), 465–6, nos 83–5Google Scholar. It is now in the Maritime Museum, Castle Cornet. Philip de Jersey sent a drawing and photograph, and calculated the vessel's capacity to be c. 3.185 litres (see next note).

75 DIV is probably an abbreviated personal name, most likely Celtic, such as Divixtus (RIB II.8, 2503.111). It is apparently followed by a note of weight or capacity, but this cannot have been expressed in terms of the libra (327.45 gm) or modius (8.754 litres). The vessel's weight has not been calculated, but it would have been several times one and a half librae.

76 By Keppie, L., ‘A lost inscription from Castlecary on the Antonine Wall’, Acta Classica 55 (2012), 69–82Google Scholar, who adds C. Irvine, Historiae Scoticae Nomenclatura (1682), 122, to the testimony of Sibbald and Gibson cited by RIB 2147. Keppie examines these early reports and discusses the reading in detail: the detachment was evidently drawn from the two legions and Brittones, who were more likely new conscripts than a formed auxiliary unit.

77 Frances McIntosh made the fragment available at Corbridge Roman Site, and provided photographs. φύλα[ξαι] is restored by RIB after a ring from Rome, but this Middle aorist imperative is difficult: the Active aorist imperative in -ξον is usual in protective amulets (‘phylacteries’). Such amulets also prefer the compounded form of the verb, διαφύλαξον, which would neatly fill the space available: see for example Kotansky, R., Greek Magical Amulets I (1994), no. 32, 15–16Google Scholar, with his note. The Caernarvon amulet (RIB 436+add. = Kotansky, no. 2) prefers the present imperative διαφύλαττε, but this is rare. The verb's object may be understood as τόν φοροῦντα (‘the bearer’) or perhaps as με (‘me’).

78 The drawing shows the first letter as Ɔ, the third as a lopsided V, surely D and E respectively.

79 The top edge, left edge and bottom edge are all original, but the upper left corner is damaged. Since the third line can be restored as LEGE FEL[ICITER], the brick must have been oblong, not square, c. 0.35 m wide. Frances McIntosh made it available.

80 RIB over-simplifies the lettering, in particular omitting the long upper stroke of F (there is no horizontal stroke here) and the incomplete letters at the end of the first two lines. In line 1, the first O is made with three strokes, the second with two strokes; it is not Q, as Haverfield thought. The bottom corner of the next letter survives, two converging strokes appropriate to B, D or E. The sequence OMO is so unusual that, unless it is an outright error for (D)OMO, the only possibility seems to be the rare personal name (H)omobonus, which may be implied by the vocative VIR BONE of the Thetford and Hoxne Treasures (C. Johns, The Hoxne Late Roman Treasure (2010), 172). In line 2, the letter after D is a vertical stroke, either I or I[I] (for E); the sequence LIINDI strongly suggests the place-name Lendinie(n)sis attested by RIB 1672, 1673 and probably III, 3376, which is thought to be Ilchester (A.L.F. Rivet and C. Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain (1979), s.v. Lindinis). Line 3 is evidently by another hand (L and E are quite different), but undoubtedly read LEGE FEL[ICITER]; whence Haverfield's suggestion of ‘a reading lesson’.

81 During excavation, but without further details being known (now CO 44298). Frances McIntosh made it available with graffiti not in RIB (see above, Nos 16–21).

82 Graffito (2) remains unsolved. To the left of ARREI, the drawing in RIB omits the end of a long diagonal stroke, and interprets casual damage below a second diagonal stroke as the tail of S. If instead these strokes were taken to be trace of an enlarged M, with the gap between ARREI and S as due to an elevated V (now lost) having been ligatured to S, [M]arrei[u]s might be suggested; but no such name is known.

83 Tomlin, R.S.O., Roman London's First Voices: Writing Tablets from the Bloomberg London Excavations, 2010–14, MoLA Monograph 72 (2016)Google Scholar.

84 Information from Tom Welsh. The Newgate Street location, within the south-east angle of the fortress, was inferred by Watkin (1886, p. 121) from the report of its discovery in the garden of Mr Kenrick, which he locates ‘on the east side of Newgate street’. Kenrick certainly lived in Newgate Street, but he leased a second property in the Groves, which is indicated by Hemingway's circumstantial report (1831, p. 396) that the stone was found on 25 May 1748 ‘in a garden belonging to Mr. Kenrick, on the banks of the Dee’. This riverside garden (‘Mr. Kenricks’) is shown in the De Lavaux Map of Chester of 1745, which also locates ‘Andrew Kenrick Esq.’ in Fleshmongers Lane (later Newgate Street).

85 Information from Fraser Hunter.

86 Information from Martin Henig, who sent a cutting from the Church Times, 18 November 2016, p. 8.

87 During fieldwork by David Walters to establish the course of the nearby Roman road from Manchester to Derby. With the owner's consent he collaborated in a closer examination, in the course of which a second, similar stone (see next note) was found.

88 The edge of the block cuts the final N, leaving only its first stroke, so the inscription originally extended onto a second block, unless a larger block has been cut down. This layout does not suggest a ‘centurial’ stone, let alone a formal building-inscription, but would suit a quarry-face inscription. However, the surface was squared off and tooled before it was inscribed, suggesting that the stone had already been detached from the quarry. But the best reason for regarding it as non-Roman is another block of the same sandstone which carries similar lettering (fig. 48b). This is a corner-stone, 0.68 by 0.30 m, 0.22 m deep, on the south-east angle of the farmhouse at 2.05 m above ground-level. There are two lines of incised capital letters: the first includes the sequence OENT (the N reversed) followed by what look like arabic numerals, apparently 19[.]7; the second consists of the un-Roman sequence HLN. This would suggest quite a modern date and initials, although the farmhouse itself appears to be late Georgian. At all events, this second inscription is undoubtedly non-Roman.