Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 September 2016

Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB (1–2400) and RIB III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415.53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

2 With the next item during excavation by Northern Archaeological Associates before the motorway upgrading by Highways England of the A1 (Dere Street) from Leeming to Barton. Hannah Russ, post-excavation manager, made them available and sent a copy of the interim report.

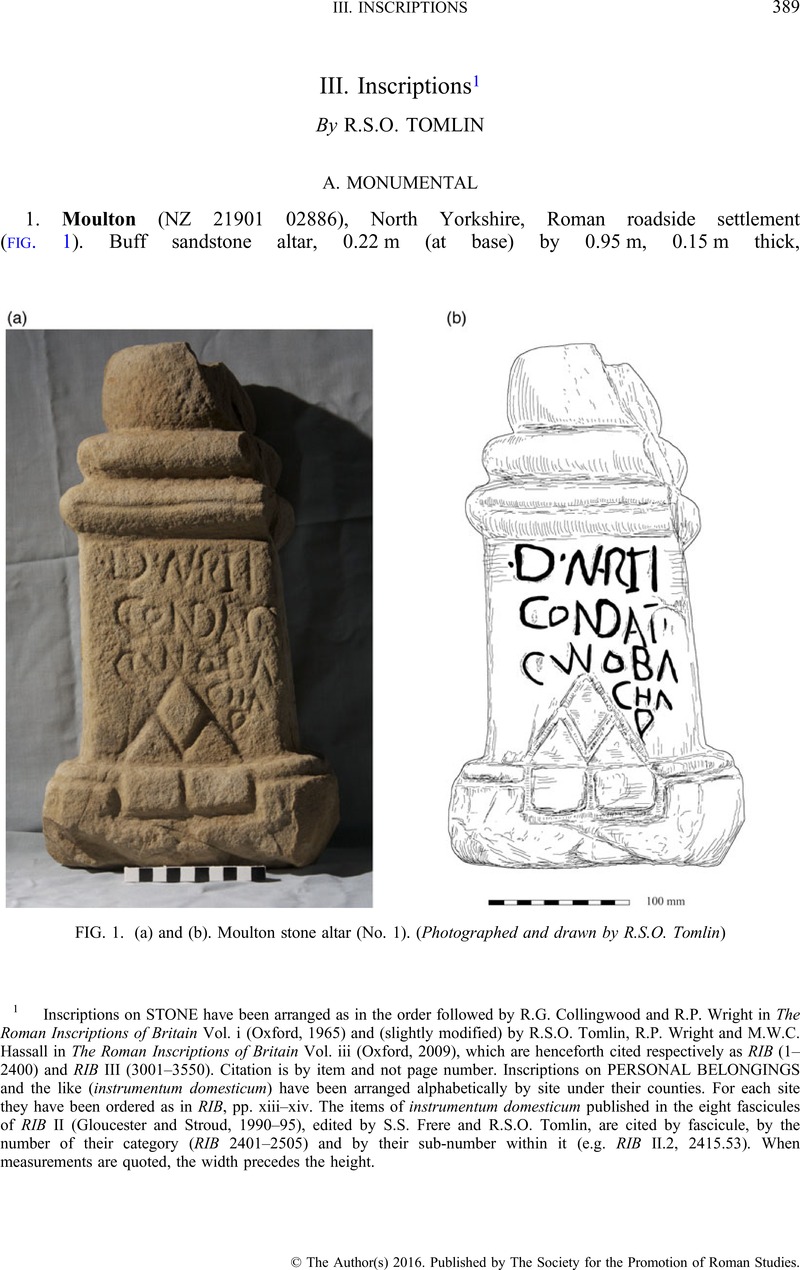

3 Line 1: the initial D is preceded as well as followed by a medial point; the fourth stroke of M is supplied by R although it is not actually joined.

2: O is reduced to fit against C; ND is ligatured; A and T are cut into a surface which is irregular due to a flaw in the stone, and followed by possible trace of a diminutive I.

3: C is almost closed by an apparent stroke which seems to be due to a flaw in the stone; VN is ligatured; there is no sign that A was completed with a cross-bar.

4: C and H are clear, but there is (again) no sign that A was completed with a cross-bar.

5: the lower vertical of P has been lost in the triangular motif to its left, but P (not D) is supported by the p(osuit) which concludes the next item. There is no good trace of a medial point after it.

Although the place-name Condate is found in Gaul (A.L.F. Rivet and C. Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain (1979), 315–16), the cult of Mars Condates (‘god of the waters-meet’) is attested only in northern Britain: the altars dedicated to him are RIB 731 (Bowes), 1024 (Piercebridge), 1045 (Chester-le-Street) and III, 3500 (Cramond). The dedicator's name Cunobacha is unique: evidently it begins with the Celtic name-element *cuno- (‘hound’), but the second element is unattested.

4 The informal II for E is unusual in ‘monumental’ inscriptions, but occurs on some altars and centurial stones. For other instances of DIIO for DEO see Britannia 46 (2015), 386, no. 4 Google Scholar (with note). The dedicator's name is uncertain. He abbreviated it for want of space, but assuming he was a Roman citizen with nomen and cognomen, the most likely expansion of VOL is Volusius (as conjectured in RIB 641) or Volumnius, although a few rare nomina would also be possible; and the most likely expansion of REC is Receptus, although Rectus / Rectinus or an unusual Celtic name like Rectugenus would also be possible. However, it is possible that he bore only a cognomen, and that VOL is an abbreviated title of Mars, like CON in No. 1 (above). Mars was ‘identified’ with many other gods, but the only instance of VOL is AE 1991, 1246a, deo Marti Volmioni, a title which seems to be unique to the region of Trier. Besides, since No. 1 is dedicated to Mars Condates, a different ‘identification’ from the same location seems unlikely.

5 During the demolition of the fireplace of a cottage at 1 and 2 Uskvale. Jean-Yves Robic of Cardiff Archaeological Consultants sent a photograph and other details.

6 The edges are all broken, but the uninscribed space to the left of IVL and VIX probably marks the left margin. Medial points were indicated at mid-height by two short strokes bisecting each other. The name of the deceased was probably preceded by the usual heading D(is) M(anibus) in the line above. After his abbreviated nomen IVL, the tail of S, the first letter of his cognomen, is just visible in the broken edge. His age at death was prefaced by vix(it), and was evidently given in years, months and days. Unusually, the third numeral was inserted within D, apparently for d(iem) I. The name would have followed of the person commemorating him, perhaps with a note of the relationship (parent or widow, for example) and a concluding funerary formula, but nothing can be deduced from the upper half of P (or possibly B) which is all that remains, except for the upper serif of another letter to the right.

7 During excavation directed by Tony Wilmott and Dan Garner for English Heritage and Chester City Council ( Britannia 36 (2005), 420–2Google Scholar), sf 10110. It is now folded long-axis and is too fragile to be opened, but it will be conserved. Gill Dunn, Senior Archaeologist (Roman finds), sent photographs and other details.

8 For other lead tags from Chester which name centuries, see RIB II.1, 2410.6–8. This century is unattested, unless it is the same as the century of Eppius Const(ans) building Hadrian's Wall just east of Birdoswald (RIB III, 3430 and 3451). The assimilation of medial [ns] to [s] is a frequent ‘Vulgarism’, as in COST for Co(n)st[ant…] at Maryport (RIB 876).

9 By a metal-detectorist, and held by the British Museum pending the result of a Treasure inquest (2014 T813). Richard Hobbs made it available there, and provided details.

10 2–3 letters have been lost in each line. Of the second O, only the left-hand curve remains, but C, G or Q are unlikely. There is no good parallel for the inscription, which seems to have consisted of two names, perhaps abbreviated. It does not seem to be religious: although Corotiacus is a title of Mars (RIB 213), it would hardly have been preceded by the dedicator's name. For the personal name Coroticus/a, see RIB 371 (with Britannia 44 (2013), 395Google Scholar, Add. (a)) and RIB III, 3053. This might be the second element of the owner's name, either as cognomen or patronymic, but the ring was apparently divided by a groove which ran round it, bifurcating at the shoulders, which would suggest that two persons were named, perhaps as recipient and donor.

11 During work by Michael Lee previous to the excavation of 2009 ( Britannia 41 (2010), 361–2Google Scholar), as noted by Bidwell, P. and Croom, A., ‘A lead sealing of the ala Augusta Vocontiorum from Chester-le-Street’, The Arbeia Journal 10 (2015), 149–51Google Scholar.

12 Bidwell and Croom (above) note that the obverse decoration and lettering are just like those of RIB II.1, 2411.90 (Leicester), but the die is not identical. The reverse is different, but may likewise have been the abbreviated name of a decurion. They observe (after Holder, P. in Wilson, R.J.A. and Caruana, I.D. (eds), Romans on the Solway (2004), 56–8Google Scholar; and compare RIB II.1, p. 88) that sealings found at a fort may well name the unit in occupation, and deduce that Chester-le-Street is likely to have been garrisoned by the ala Vocontiorum in the third century. Its whereabouts are otherwise unknown after Newstead was evacuated in c. a.d. 180, and Chester-le-Street was certainly garrisoned by an ala in a.d. 216 (RIB 1049).

13 By Albion Antiquities on eBay, where it was accompanied by photographs and sold as ‘Very Large Roman Jug with inscription on body’. Communicated by Guy de la Bédoyère.

14 Unless the first stroke is an unfinished L, the graffito appears to be complete, and would imply the proper noun Ebralinis, whether it were a place-name in the ablative plural or a personal name, the genitive of *Ebralo. There seems to be no other instance of either.

15 With the next item (sf 1057) during excavation ( Britannia 34 (2003), 337–8Google Scholar) directed by Mike Roy for the former Essex County Council Field Archaeology Unit. Louise Rayner of Archaeology South-East made them available. The site adjoins Elms Farm ( Britannia 29 (1998), 85–110 CrossRefGoogle Scholar).

16 The graffito, which is complete, is an abbreviated personal name with many possibilities.

17 The tip of L survives in the broken edge, but its horizontal stroke is much shorter than that of the second L. The graffito is a woman's name in the genitive case: Marcellina is quite likely, since this is a common name and is found in London in the same ‘Vulgar’ spelling of the genitive termination with e for ae ( Britannia 40 (2009), 333, no. 29 Google Scholar, MARCIILLINII).

18 By a metal-detectorist (PAS ref. GLO-988544, Treasure ref. 2016 T231). Information from Martin Henig and Kurt Adams, Gloucestershire and Avon Finds Liaison Officer.

19 Both letters are carefully serifed, but the second horizontal of F is now rather faint. To the left of V, the curving mark is casual. For the inscription compare RIB II.3, 2423.28 (Southwark), a copper-alloy ring with the bezel inscribed VT F.

20 During the excavation published in Woodward, A. and Leach, P., The Uley Shrines: Excavation of a Ritual Complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire: 1977–9 (1993)Google Scholar, in which it is noted at p. 128 as no. 34 (sf 936). It will be published with fuller commentary in the final report being prepared on the inscribed lead tablets.

21 Line-by-line commentary.

1, Genitus. Although Genitor (‘begetter’, i.e. ‘father’) is attested as a personal name, this seems to be the first instance of Genitus (‘begotten’, i.e. ‘son’).

2, [g]enio. The restoration is confirmed by the repetition of genium in 6, but this is the only Uley tablet to identify Mercury as a genius. The writer probably meant to address the god's genius, as in Britannia 23 (1992), 310, no. 5 Google Scholar, rogaverim genium numinis tui (‘I would ask the genius of your divinity’).

4, fecerit. The object of this verb ends in -um, not -em, which would exclude fraudem (‘wrong’) but suggest furtum (‘theft’), but this too is excluded by the two preceding diagonal strokes which imply a or d. The writer may have conflated the two nouns, as in Britannia 40 (2009), 327, no. 21 Google Scholar (Leicester), frudum(!) fecit.

5–6, involaverit. The object of this verb is divided between the lines, and its letters are badly corroded, but the traces are consistent with an|ulum (‘ring’), a frequent object of theft.

6–8 is a series of mutually exclusive alternatives, with 6 probably ending with si libera si (‘whether free woman or slave-girl’), but the genitive [mu]lieris (‘of a woman’) is difficult.

9, permitt(…) eum would be an easy slip for permitt(e) eum (‘permit him’), but the imperative would be rather abrupt towards a god; the usual formula is the subjunctive non permittas.

10–12 are badly damaged and do not contain any recognisable formulas, unless the sequence bllat (12) (the double ll is certain) is a mistake for ambulat. This seems quite likely, since there is good trace of the tail of m before b. Not to be able to ‘walk’ (ambulare), as opposed to ‘sitting’ (sedere) and ‘lying’ (iacere), is a typical curse, for example in Tab. Sulis 54.

11, pede (‘with his foot’) may be an elaboration of this ‘walking’, previously unattested.

13, nec manducat. The verb ‘to eat’ is contrasted with bibere (‘to drink’) in curses of ill-health, to which Tab. Sulis 41 adds the subsequent process of elimination, ‘defecation’ (adsellare) and ‘urination’ (meiere, restored). This would explain the contrasting verbs in the phrase nec | sedit nec magiat (13–14): sedit (for sedeat), ‘sitting’ in the sense of adsellare (‘come to stool’), and magiat (for meiat, by confusion with mingere, the alternative form of meiere) for ‘urinate’. Compare Uley no. 5 (sf 5050), ne maiet ne cacet.

15–17, ad templum tuum repraesentaverit. The restoration of stolen goods ‘to the temple’ is frequent, and for this verb, with its sense of ‘paying ready money’, compare Uley no. 1 (sf 1180). 17–18 is too corroded for restoration, and nothing is suggested by the context.

22 By a metal-detectorist and recorded by the PAS (ref. IOW-DA5661). See this volume, Worrell, S. and Pearce, J., ‘Finds reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme’, Britannia 47 (2016), No. 22 Google Scholar.

23 Reading from left to right, with O supplied by the circular loop of R.

24 This is is the first example from Britain, but others have been found in southern Germany, Romania and Bulgaria. For full details and discussion see Pearce, J., Basford, F. and Worrell, S. ‘Mars, Roma or Love, actually? A new monogram brooch from Britain’, Lucerna 50 (2016), 22–3Google Scholar.

25 PAS ref. LANCUM-83C97B, communicated by Sally Worrell, which probably conjoins LANCUM-8DBAC3, found in 2012.

26 Comparison with RIB II.2, 2415.39 (Caerleon), a trulla stamped ΛLΛ o I o TH (or THR), would suggest that a cavalry ala is being named, but V can hardly be a numeral (‘5’) since almost no ala was numbered more than II (‘2’), and the letters match nothing in J. Spaul, ALA2: the Auxiliary Cavalry Units of the Pre-Diocletianic Imperial Roman Army (1994).

27 PAS ref. LEIC-30A5D5, communicated by Sally Worrell.

28 For other copper-alloy rings with a two-line inscription divided by a horizontal groove, see RIB II.3, 2422.47 (Wroxeter) and No. 29 below (Flixton). In the Woodhouse inscription mihi (‘to me’) should be understood, implying that the ring is a gift to one who will ‘give (me) life’: compare RIB II.3, 2422.75 (London), an iron finger-ring inscribed DA MI | VITA, da mi(hi) | vita(m). In both cases, the final -m has been omitted because it was not sounded.

29 As noted in Britannia 45 (2014), 445, no. 24 Google Scholar.

30 R.S.O. Tomlin, Roman London's First Voices:Writing Tablets from the Bloomberg London Excavations, 2010–14, MoLA Monograph 72 (2016), to which refer for photographs and fuller commentary. Altogether it publishes 79 legible texts, many quite fragmentary, as well as 104 illegible ‘descripta’ including uninscribed tablets of unusual format, and two ink tablets.

31 Classico is either dative or ablative, but the loss of the preceding text makes the context unknown. The only equestrian officer known to have borne this unusual cognomen is the Treveran noble Julius Classicus (Devijver PME I 46), who in a.d. 70 was commanding an ala when he joined the Batavian Revolt. Since a tribunate would have intervened, his first command must have been an auxiliary cohort in the early 60s. This tablet was found in an archaeological context of c. a.d. 65/70–80, which supports the identification, especially since another Treveran noble, Julius Classicianus, became procurator of Britain in a.d. 60/61: Classicus has already been suggested as his kinsman (A.R. Birley, The Roman Government of Britain (2005), 304, no. 11), and it may now be further suggested that Classicianus secured a commission for him in his (Classicianus’) new province. Previously the cohort was first attested in the Brigetio diploma of a.d. 122 (CIL xvi 70, cohort no. 36, tabulated in RIB II.1, table 1), but it can now be seen as one of the eight auxiliary cohorts from Germany which reinforced the garrison of Britain in a.d. 61 (Tacitus, Ann. 14.38). Other tablets allude to the Vangiones (WT 48) and the Lingones (WT 55), both of which are listed in the same diploma (cohort no. 8 and cohorts nos 5, 23, 29, 31 respectively).

32 The archaeological context is pre-Boudican (c. a.d. 53–60/1), which matches the date of the tablet. Its content illustrates Tacitus’ characterisation of London before its destruction (Ann. 14.33) as being ‘very full of businessmen and commerce’ (copia negotiatorum et commeatuum maxime celebre). This is not only the earliest dated text from Roman Britain, it is the City of London's first financial document.

The two freedmen may be acting on their own account, but more likely as agents of their patrons. The only other instance of the cognomen Tibullus seems to be the poet himself, but since slaves often received a fanciful name which they retained as freedmen, perhaps Tibullus’ master had literary tastes. Since he is identified by his cognomen, Venustus, not his praenomen like the patron of Gratus (where the initial letter of Spuri has been omitted by mistake), he was probably not a Roman citizen. If not, he cannot be identified with M(arcus) Rennius Venustus in the next item (WT 45).

The phrase scripsi et dico me | debere is formulaic, as are last two lines (quam pecuniam, etc.); for parallels see the fuller commentary.

ex{s}, like condux{s}isse in the next item (WT 45), is an example of s being intruded after x to reinforce the [ks] sound, which is frequent in British Latin.

After mercis are extensive traces of a previous draft, which was probably … quam vendidit et tradidit (‘which he has sold and delivered’, the subject being Gratus). The writer then chose the passive construction instead, but omitted est by mistake.

33 The consular date is certain, but instead of writing Celso, the scribe wrote Cexiii, apparently a false anticipation of the day-numeral. There is no trace of correction. At the end of the line, he interlineated -mbr(es) to complete the date, which is neatly matched by the archaeological context, immediately post-Boudican (c. a.d. 60/1–62). This contract is therefore evidence that London and Verulamium (St Albans) both recovered quickly from their destruction in a.d. 60 or 61 with the loss of 70,000 lives (Tacitus, Ann. 14.33) and supports the earlier date.

The perfect infinitive condux{s}isse requires a finite verb, which must have been omitted by oversight; probably the formulaic scripsi et dico (‘I have written and say’), as in the previous item (WT 44).

At the end of line 4, the scribe began to write ‘London’ by mistake for ‘Verulamium’, deleted it by smoothing out the wax, which would have left no trace in the wood beneath, and then realised that he would not have enough space for Verulamio, so he postponed it until line 5.

The size of the ‘loads’ (onera) is not specified, whether they were by wagon or by pack-animal, but another tablet (WT 29) refers to the loss of ‘beasts of burden’ (iumenta), ‘investments which I cannot replace in three months’ (conpe(n)dia quae messibus(!) tribus reficere non possum).

(denarii) quadrans. The basic meaning of quadrans is ‘one-quarter’, and it was thus applied to weights and measures, but here it is preceded by the denarius symbol (a bold X now missing its medial stroke) and evidently means one-quarter of a denarius, the equivalent of four asses. This seems to be the first explicit instance, but many Vindolanda accounts specify (denarii) (quadrantem), abbreviating quadrantem like denarii to a symbol. quadrans is also used of a very small coin, the quarter-as, but this would be absurd for a day's work by a driver and draught animals, when a soldier earned 10 asses a day (Tacitus, Ann. 1.17), forty times as much.

vecturae is rather incomplete, but there are sufficient traces, besides its being demanded by the context. It occurs in Tab. Vindol. III, 649.ii.12 and 14 in the sense of ‘carriage-moneys’ (for which see the editors’ note), and also in an unpublished stylus tablet from Vindolanda (Inv. no. 88.836).

This payment of four asses per load is immediately qualified by a ‘condition’ (ea condicione) involving ‘London’ (Londinium) and the sum of one as, where the numeral ‘1’ is preceded by the symbol found five times in Tab. Vindol. II, 186, which is described by the editors as ‘a longish vertical which slants to the right and has a short, more or less horizontal tick placed centrally to the left’. Unfortunately the succeeding words are damaged and the reading is uncertain; the ‘condition’ is likely to have been that one-quarter of the fee was withheld until ‘the whole’ (om[n]e[m]) had been delivered.

34 PAS ref. NMS-B6A4F4, communicated by Sally Worrell. Martin Henig comments that the best match is a cornelian gemstone of Augustan date from the colonia at Xanten (G. Platz-Horster, Die antiken Gemmen aus Xanten (1987), 61 with pl. 21, no. 112). See also this volume, S. Worrell and J. Pearce, ‘Finds reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme’, Britannia 47 (2016), No. 20.

35 ND is ligatured, and the lettering is broken by the olive branch. It is most unusual for an intaglio to be inscribed with a name: for examples see RIB II.3, 2423.

36 With the next two items during excavation by the Upper Nene Archaeological Society directed by Roy Friendship-Taylor, who made them available. They will go to the Society's museum at Piddington.

37 This might be read inverted as IVVC[…] or IVVO[…], but it would be inconsistent for there to be no letter-spacing between V and V, and a difficult letter-sequence would result. Both tiles were locally made in the same fabric, and were inscribed by pressing them onto wooden moulds in which letters had been cut. This is exceptional, since separate impressed dies were used to stamp Roman brick and tile. Although the remaining letters are too few for identification, they presumably named the tile-maker(s).

38 The feminine form of Candidus, quite a common name; for examples of Candida on samian, see RIB II.7, 2501.117 and 118.

39 PAS ref. SF-4D045C, communicated by Sally Worrell.

40 V might be an incomplete N, and I the vertical of another incomplete letter. But EVST can hardly be read, although two instances within an oval cartouche are known from London (RIB II.1, 2411.266 and Britannia 45 (2014), 445, no. 26 Google Scholar). There is no other possible match in RIB II.1, 2411.

41 PAS ref. SF-4D6761, communicated by Sally Worrell.

42 N resembles VI, but the resulting sequence would be difficult, whereas Cunicius is acceptable as a personal name formed from the Celtic element cuno- (‘hound’) and the suffix -icius. It is not attested, but compare Cunitus (RIB II.2, 2416.2) and Cunicatus (RIB II.8, 2503.236).

43 During excavation by Archaeological Services, Durham University, directed by Richard Annis. It will go to the Great North Museum. Alex Croom sent a rubbing and other details.

44 Despite the letters being so close to the broken edges, the graffito seems to be complete. Iunius and its feminine form Iunia, although a common Latin nomen, is often found by itself as a cognomen. For instances of Iunia from Britain, see RIB II.7, 2501.275 (Great Chesterford) and 276 (Hacheston, Suffolk); II.8, 2503.296 (Brompton-on-Swale). The genitive termination -e for -ae is a trivial Vulgarism; the pronunciation would have been the same.

45 During excavation directed by Simpson, F.G. and Richmond, I.A. which continued that reported in JRS 28 (1938), 172–3Google Scholar. The sherds, which are stored by Durham University Museums (acc. no. DUMA:1984.26), were made available by Alex Croom.

46 The loop of R is unclosed, but K seems unlikely. The first stroke of II (for E) has been lost. The second II awkwardly abuts T. The final I is extended downwards to mark the end of a name in the genitive case. At its foot is a separate incision (or probably two incisions) which are unrelated; perhaps the beginning of a graffito which was never continued. R[I]CIITI must be understood as a blundered RIICIIPTI (Recepti), P having been omitted by mistake; its loss cannot be explained as a ‘Vulgarism’. The name Receptus (‘received’) is well attested, and has already been found in Britain (RIB 155).

47 During the excavations reported in A.S. Anderson, J.S. Wacher and A.P. Fitzpatrick, The Romano-British ‘Small Town’ at Wanborough, Wiltshire: Excavations 1966–1976 (2001), where it is noted on p. 316 (no. 25) and drawn on p. 315 as fig. 110, no. 25. The reference was communicated by Peter Warry, who sent a composite drawing (above, fig. 26(b)) made from it and another stamped fragment also stored by Swindon Museum, but not necessarily from Wanborough, which taken together read IANV[…].

48 Unless abbreviated or in the genitive case, Ianuari. The die is otherwise unknown, but other private tile-makers are attested at Wanborough: see RIB II.5, 2489.18 (IVC DIGNI) and 44G (initials).

49 On the surface by a metal-detectorist. For the site, see Britannia 46 (2015), 299–300 Google Scholar. Peter Halkon, University of Hull, sent a photograph and other details.

50 It is unclear whether the graffito is complete, and thus equivalent to an impressed stamp. A conventionally stamped tile of the Sixth Legion has also been found at the site, but this informal inscription is most unusual. There is nothing like it in RIB II.5, 2491 (tile graffiti).

51 During excavation by Northern Archaeological Associates before the motorway upgrading by Highways England of the A1 (Dere Street) from Dishforth to Leeming. It will be published in their forthcoming report by Paul Holder, who sent photographs and a copy of his very full account which is briefly summarised here.

52 CAPITALS are surviving letters; lower case italics are letter-by-letter restoration of letters lost. Abbreviations not resolved. (i) preserves part of the titulature of Antoninus Pius as consul III, i.e. after a.d. 139 but before 145.

53 (ii) preserves part of a grant of citizenship dated by its formulation to December 139 or later, and part of the suffect consulship of Antonius, whom Holder (above) convincingly identifies as Quintus Antonius Isauricus in a.d. 140.

54 PAS ref. YORYM-DFDFD8, communicated by Sally Worrell.

55 For other copper-alloy rings with a two-line inscription divided by a horizontal groove, see RIB II.3, 2422.47 (Wroxeter) and No. 14 above (Woodhouse). The horizontal strokes of E can just be seen, but T and I are now indistinguishable; but see CIL xiii 10024.86a, b, c and d for other examples of finger-rings inscribed AVE | VITA. vita (‘life’) is an endearment addressed to the recipient of the ring.

56 During excavation directed by Howard Mason for the Ancient Monuments Division of the Department of the Environment (http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/caerleon_cadw_2010/). The graffito was not noted then, but was identified in 2015 by Mark Lewis, curator of the National Roman Legion Museum, Caerleon, who sent a photograph and other details. The vessel (NMW acc. no. 2014.2H/15.1) is dated by Peter Webster to the mid/late second century.

57 Also from Caerleon, compare RIB II.8, 2503.116, [feli]citer (centuriae) Ael(i) Romuli. The present graffito may therefore not be complete, but would have named the person(s) for whom ‘good luck’ was invoked.

58 By Martin Henig for his forthcoming publication with Penny Coombe and Kevin Hayward of Roman stonework from the cathedral. The drawing ( fig. 31) is reproduced by courtesy of the Chapter Library (Irvine Papers, I, folio 28).

59 This is a well-attested alternative to the form Tertullo et Sacerdote co(n)s(ulibus), the second consul being identified by two cognomina as Q(uintus) Tineius Sacerdos Clemens. Haverfield suggested the consuls of a.d. 184 (see note to RIB 231), but this would require identifying them by praenomen, nomen and cognomen, which would be less likely. The drawing confirms that the incomplete letter in the line above is A, or possibly M.

60 ‘Second’ (for ‘First’) was by confusion with RIB 1466, which had just been cited. The correction was noted by Luke Ueda-Sarson and communicated by Scott Vanderbilt.

61 This volume, Hunter, F., Henig, M., Sauer, E. and Gooder, J., ‘Mithras in Scotland: a mithraeum at Inveresk (East Lothian)’, Britannia 47 (2016)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

62 V cannot be distinguished from ‘open’ (unbarred) A. The variations seem to be unsystematic, and the difficulty compounded by transcription errors, for example in (i) 2 and (ii) 7. For further commentary on the names, see Britannia 43 (2012), 402–3Google Scholar.

63 Information from the Bowes Museum, where they are stored in the West Lodge, although this may not be their final location.

64 Information from Andrew Birley, Director of Excavations, Vindolanda Trust.