The Chairman (Mr A. H. Watson, F.F.A.): I am Alan Watson and, as well as being a member of the Council and the Management Board, I chair the Scottish Board of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA). It is my pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 IFoA spring lecture.

Tonight’s lecture is a slight departure from our usual thought leadership events. It is the first time that the Scottish Board has joined with the IFoA Public Affairs and Research team to present a joint lecture. I am pleased that this lecture will showcase the work of the Scottish Board and the partnerships that exist within the IFoA.

The IFoA is committed to showing how actuarial science can adapt in a modern and ever-changing world. Our profession is evolving. We are ready to engage and collaborate with other professions to shape and make sense of the future world.

We do this by facilitating and promoting the work of our members and volunteers through our research and policy work. But we also hold events for our members and the wider public to give a voice to our profession, which includes the two flagship lectures that we deliver each year, one in the spring and one in the autumn. Our lectures are delivered by experts from outside the actuarial profession who are leaders in their fields. They provide insights on subjects of relevance not only to actuaries but also to those outside our profession in business, politics and public service.

As a chartered body, we have a duty to speak up where we can inform debate, to offer an expert opinion, and to offer tangible solutions to real-world problems.

Tonight, we will be tackling a topic that has dominated the news for months. I do not think that we could have picked a better date! In our correspondence, Sir John was happy with early March if there was not an election the following day.

Perhaps we assumed that 2 weeks before the due exit day, we would know a little more about how, when and if we were leaving the EU. But, as we sit here tonight, MPs are in the process of voting on a no-deal Brexit after rejecting the Prime Minister’s proposals last night.

It is not often that we witness politics as volatile and unpredictable as this. The final nature of Brexit will undoubtedly affect the industries in which we work as actuaries and the way in which we live our day-to-day lives. So whether the outcome will be for better or worse, we cannot yet say. But Brexit has generated such polarised viewpoints that it is surely no surprise politicians still cannot seem to decide how it should be implemented.

At the referendum, the majority of voters said the UK must leave the EU; but, more than 2 years down the line, are we any further forward with honouring that result? Have people’s opinions changed? Will we be asked to vote again? And do any of these outcomes truly reflect the result of the 2016 referendum? I cannot answer these questions here tonight – I will leave that to our guest speaker.

If there is anyone who can help us understand how Brexit came to be, we think it is Professor Sir John Curtice. He gives us our best shot at understanding what has been going on in the past 2 years and is best placed to provide insight into the subject that is dear to our hearts as actuaries: what might happen in the future.

Sir John is well known for his expert research and polling methods in electoral behaviour. It is for this reason that the Scottish Board asked him to come and share his experience. He is a professor of politics at Strathclyde University in Glasgow and senior research fellow at NatCen Social Research.

He has written extensively about voting behaviour, elections and referendums in the UK as well as on British politics and social attitudes more generally. He is a fellow of the British Academy, the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Academy of the Social Sciences. He is also an honorary fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. However, as Britain’s pre-eminent psephologist, he is more familiarly known as the man who won the 2017 election.

He is a regular face in the media, giving impartial insight into the facts and figures behind the driving trends of UK electoral politics. With that in mind I am delighted to introduce our speaker for this evening, Professor Sir John Curtice, who will be evaluating the question: Brexit: Democratic Success or Failure?

Prof J. Curtice: I guess some of you are probably asking yourselves: how is it possibly going to take him 40 minutes to answer the question that he sets himself? Is it not painfully obvious? You only need to stand outside College Green for 5 minutes to be aware of what you think the answer might be.

Well, if you stand outside College Green, one of the things you will discover straightaway is that there is quite a division in public opinion. Standing outside College Green and constantly making a noise behind the media is a group of (a) ardent Brexiteers, and (b) a group of ardent Remainers, and they stand out. Even yesterday evening, when the weather in London was almost as inclement as it usually is in the west of Scotland, they were still out there promoting their cause.

Also, we should have perhaps realised that this is 13 March and maybe we should have anticipated that we would not necessarily all be clear on this by today.

I want us to stand back a little from the immediate headlines and parliamentary manoeuvres.

Never has the BBC Parliament Channel been more exciting, frankly, since about mid-November because every time the Prime Minister stands up she is given rather a hard time. It now matters which way MPs decide to vote because they are voting for themselves. It makes for great sport if not necessarily for great government.

By saying “Brexit: Democratic Success or Failure?” I want to address the fact that we are talking about how a referendum result is being treated. There are a couple of criteria that I think we can use in trying to judge whether or not a referendum is a success or a failure democratically.

One is to say that this is an instrument that is intended to bring public policy into line with public preferences. General elections are a way for voters to send a signal. But general elections are about many issues and not just about the positions of the parties; they are also about what you think about the merits or otherwise of the politicians promoting those priorities. It is a multifactorial judgement.

With a referendum, at least you can put an issue before the public and ascertain what the public think about it. We can therefore ask ourselves: is a referendum, and is the Brexit referendum, successful in bringing public policy into line with public preferences?

Out of that potential criterion, there is a question that is commonly asked about referendums. That is, do the voters have clear public preferences or policy preferences in the first place that could inform public policy? There is long-standing literature in my profession about whether or not voters are, or are not, sufficiently knowledgeable in referendums and, if they are, under what circumstances. And are they able to use shortcuts in order to be able to come to a judgement that would be as good a judgement as if they were indeed perfectly informed?

That is a rich literature, but it is not the literature that I want to get into this evening. I want to reach something that I think is the other important criterion so far as the June 2016 referendum is concerned: whether or not the preferences that the public expressed in a referendum have been implemented.

Once you have asked that question, this is not about, “Were people voting sensibly?” It is about what we do about the result. That is the question on which I want to focus.

That raises two questions. The first is: are we clear from the outcome of the referendum what people’s preferences were?

The second question that it raises is that when we hold a referendum and we say that if the public vote this way that is what we will do, it assumes that the state can deliver.

But, of course, one of the crucial attributes of the Brexit referendum is delivering what the public are thought to have expressed as their view in June 2016 did not simply lie within the purview of the UK government to deliver. Rather, this was something where it would at least have to go through a process laid down by the Lisbon Treaty and Article 50, with which we are now all familiar, and that that laid down the process and a timetable and a procedure by which we can extricate ourselves from the EU and perhaps then subsequently form a relationship.

There are echoes of this issue arguably in the Scottish independence referendum with which those in Edinburgh and Glasgow will be familiar. The Scottish government proposed a plan as to what independence would look like. One thing that emerged from the Scottish independence referendum is that delivering what was in the Scottish government’s plan was not solely within its purview to deliver. For example, it said, “We want to carry on using the pound” but the UK government said, “No, you will not be allowed to do so.” There were other issues of that kind as well.

When we hold a referendum, the people who are proposing this referendum say, “We will implement your wishes.” It assumes that whatever state body is making that promise has it within its ability to deliver.

We have had referendums where it has been possible. When we had the referendum on introducing the Alternative Vote in the House of Commons, back in May 2011, the legislation was written, it had been passed; it just needed the public to say yes. If the public had said yes, the rules would have been changed. There is a clear example of where this issue does not arise. But with the Brexit referendum it does.

With those observations, and with the focus, then, on how effectively Brexit has been implemented, I want to ask three questions.

The first, which flows out from the first issue I raised, is: What did voters want? What were they expressing in the ballot box?

The second question is: If the point of this process is to satisfy public opinion, what do the public think of the outcome so far? We do tend to forget in the immediate heat of the moment that even if Theresa May were to get her deal through tomorrow, that simply starts round two of the negotiations during which most of the issues that we have been talking about will be settled. We have settled very little about the Brexit process so far.

Thirdly, that was what the public said in June 2016, but is that still what they want to say now?

In the light of the outcome so far, and what Brexit therefore might mean, are they still in favour or not? That is what I want to focus on. Yes, I have orientated us towards looking at public opinion.

What do voters want? The truth is that what voters wanted was what was not on the menu – at least so far as the theology of the EU was concerned.

I am going to show you data from all sorts of sources. Some of it comes from some research I have done. I have been tracking people during the Brexit referendum, the Brexit process, trying to ask questions that do not include words like “single market,” “customs union” and “freedom of movement.” We are trying to turn it into plain English.

This is the question: Do you think we should allow EU companies to be able to trade in the UK freely in return for British companies being able to do so inside the EU? This is trying to explain free trade in plain English.

A high proportion (over 86%) of people said, “Yes, that is something I would like to see emerge out of the Brexit process.” 3% said that they would not.

As you can see, there is no argument about maintaining free trade with the EU. It therefore follows that, above all, there was no argument among Leave voters about wanting to maintain free trade with the EU. Both Remainers and Leavers are almost entirely at one on this issue. They were immediately after the referendum and they have continued to be during the Brexit process.

But, of course, the EU says that if you want to have free trade, among other things, you have to have freedom of movement of labour. We also know that one of the issues that was important in the referendum, and probably was central to the result, was the concern about immigration.

This is one of a number of questions that I have used: Do you think that people from the EU who wish to come Britain to live and work should have to apply to do so in exactly the same way as people from outside the EU? This is now going to be the principle that the British government will use if we do manage to extricate ourselves from the EU.

The proportion of people who have supported that proposition has fallen from 74% to 59% since the referendum. Those who are against have increased from 13% to 20%. This is more controversial. There are some Remain voters out there who will say, “I do not agree with this.” That principle is basically code for ending freedom of movement. Although this is by no means a unique source of evidence on this, support for wanting to do something about curbing immigration has declined, although it is still the view of the majority.

The public has no problem with free trade. Freedom of movement? Yes, there is a problem. So although economists would want to argue that you want to have capital and labour moving together, the public do not see it in the same way.

If you want to know what the public wanted out of Brexit, they wanted what was not on offer. I am going to argue that, in part, the reason why we are where we are is because of that fundamental contradiction between the structure of public opinion and the structure of the elite debate. Public opinion is not required to follow the rules that are laid down by organisations. In this case, they certainly did not.

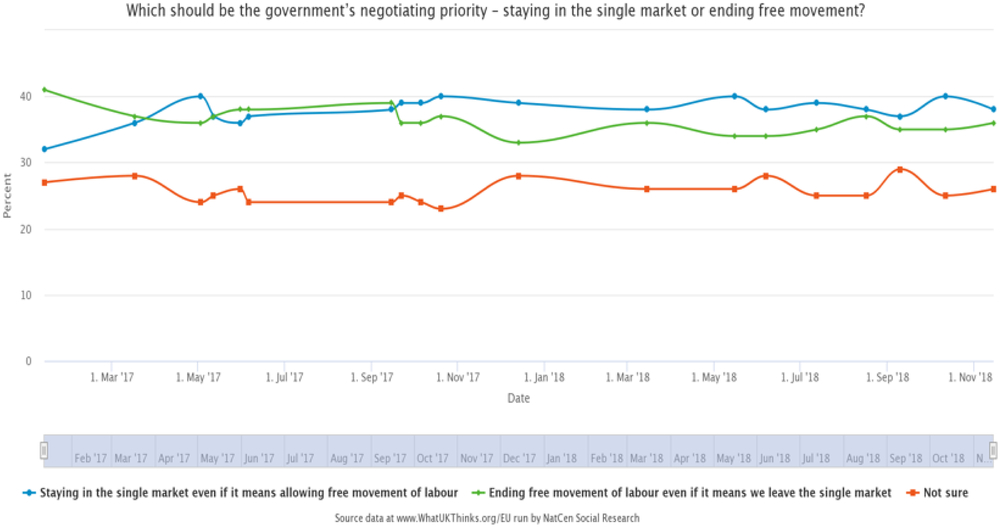

You ask people what matters more. Is it remaining inside the single market or is it ending freedom of movement? In the graph in Figure 1, the blue line represents those people who say the most important negotiating priority is staying in the single market. The green line is those who say that it is ending free movement.

Figure 1. Opinium: single market versus free movement.

The red line represents those people who say that they cannot answer the question. That, in part, will be people not knowing what their view is, but it is probably also an indication of people indicating that that is not a choice that they want to make.

But you will then notice that once we start to ask people to choose in the way that Michel Barnier and the EU think that they should choose, public opinion in the UK begins to split pretty much 50/50 between the two options. The concern about immigration is a bit lower than it once was.

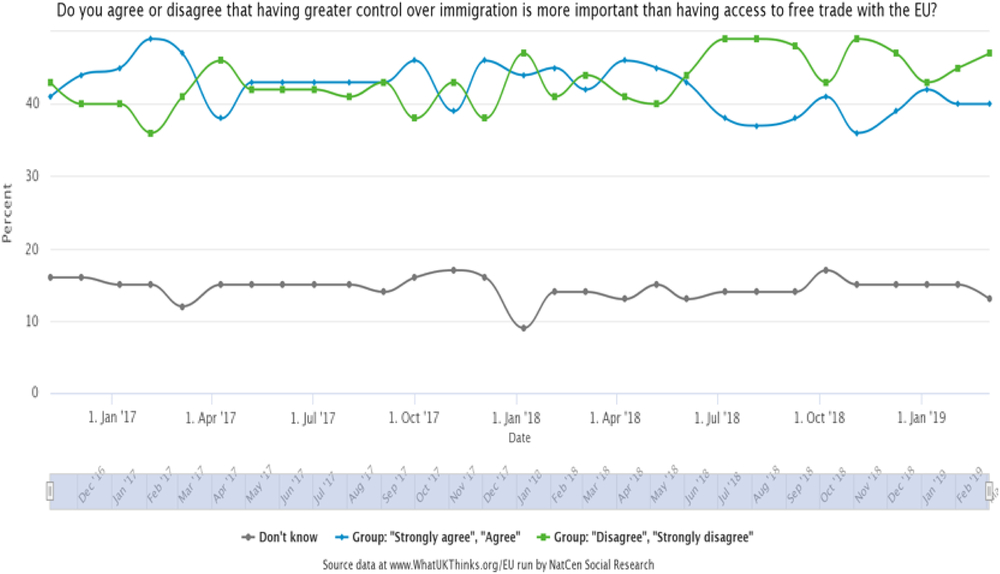

Here is another piece of evidence from another company, which asked a somewhat different question. Do you agree or disagree that having greater control over immigration is more important than having access to free trade?

The green line in Figure 2 represents those people who disagree. Those are free traders. The blue line is those who prioritise immigration. In the early years of the process, we were evenly divided. More recently, the concern about immigration has become somewhat less important.

Figure 2. ORB: immigration control more important than free trade.

You can see how the public begin to divide 50/50. I personally have had my go at this, Noel Edmonds style. This is my “Deal or No Deal” question. I assumed that virtually everybody in the UK was in favour of maintaining free access to the single market.

The question is: If the only way we can get British firms still able to trade freely inside the EU is to allow people from the EU the right to come here, should we do that deal or not? If you ask that, while again if we go back to the early years, it is pretty evenly split between those who say we should do the deal and those who say we should not. Now it has bounced around thereafter and again, as you might expect from what I have shown you already, the concern about staying in the single market seems more prevalent.

Again, whereas I could get complete unanimity virtually on the principle of free trade, once we start saying there is a trade-off here, it becomes more difficult. Above all, of course, what you discover is that although both Remainers and Leavers – a majority of them – ideally want to end freedom of movement but maintain free trade, force them to choose and they begin to polarise.

Forced to choose, two-thirds of Remain voters go for a single market. Only 10% say to end freedom of movement. On the other side of the fence, three out of five Leavers prioritise ending freedom of movement. Only 14% prioritise the single market.

Once you start to force the public to choose, the potential for polarisation of public opinion in the UK is evident. There is a similar picture from my own research. The Remainers are willing to do the deal; the Leavers, for the most part, reluctant to do so.

The potential for polarisation of public attitudes was always there. But, of course, what has been true, and it is true both of the government and the Labour Party, both our principal political parties have been trying to seek a compromise. Theresa May has had her red lines, of getting out of the European Court of Justice, ending freedom of movement and the right of the UK to make its own trade deals.

Once you accept those red lines thereafter, she was then after as frictionless a trading relationship as possible. So while on the one hand, she was articulating what she took to be the principal concerns of Leavers, but then tried to take on board the economic concerns of Remainers.

The Labour Party is in favour of a softer Brexit, but the rhetoric of the party is that they want to bring together the 52% who voted to leave and the 48% who voted to remain. So, yes, the Labour Party says we should leave the EU but then wants to remain inside a customs union and wants to have a close alignment with a single market – by the way, we still do not want freedom of movement – and Germany does not like the rules that curb state aid.

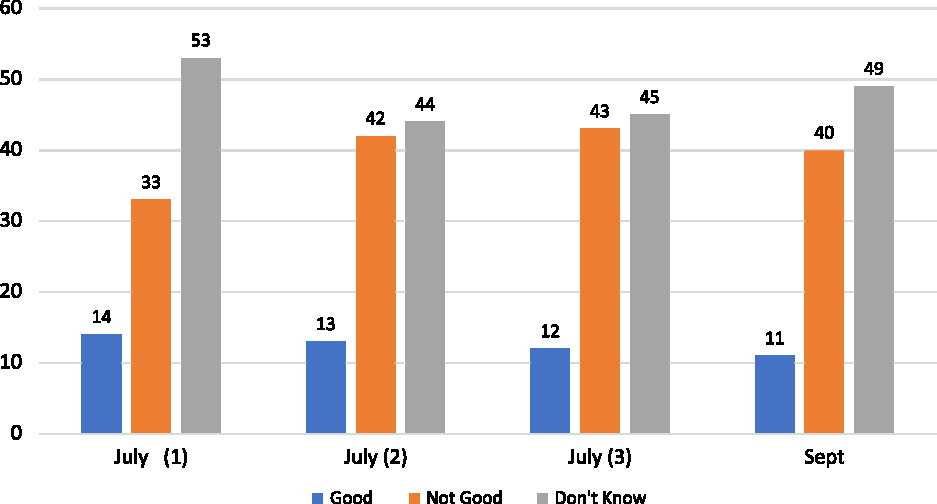

The first clear revelation of what Theresa May’s compromise meant was the Chequers agreement of July of last year. You can see in Figure 3 the data on what the public thought of the Chequers compromise.

Figure 3. Chequers: a first attempt at compromise.

Even by September, half the people were saying, “I do not know whether this is good or not.” This is data from YouGov. But among those who do know, only 10% said, “It sounds alright” and 40% said, “No it does not.”

Second, here was a development in the Brexit process that succeeded in uniting the country! Both Remainers and Leavers were more or less of the same view by around 4–1 that it did not sound too good.

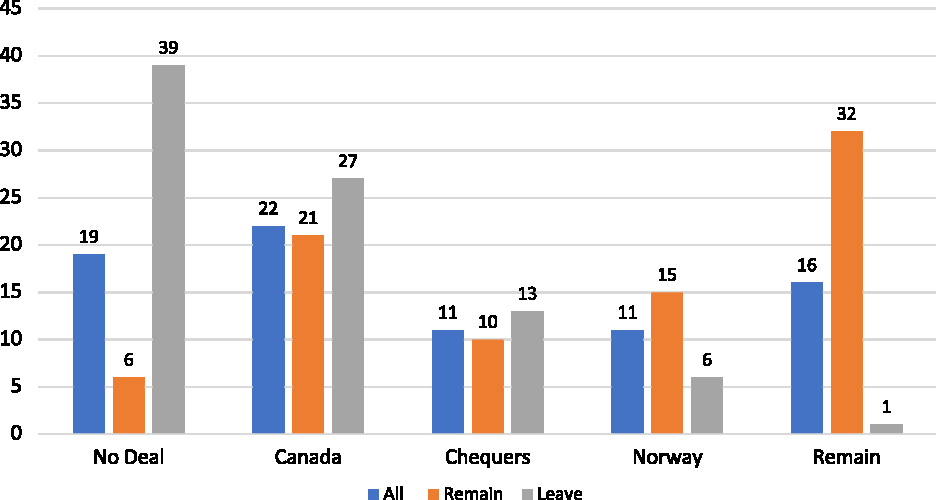

Indeed, Figure 4 shows the picture a little after Chequers, by which point we start polling about the variety of possible Brexits that we might have. This is an example from BMG Research that was done in September.

Figure 4. Fragmented – but polarised.

It is a range from, on the left-hand side, the most Brexit option to, on the right-hand side, the most Remain option. Reading from left to right, we have “No Deal” first. Next is “Canada,” which means a loose free trade arrangement whereby you accept each other’s rules but you have the minimum extent of regulatory alignment and minimal rules in terms of permitting freedom of movement. Next is “Chequers”; then “Norway,” officially being inside the single market, not being inside the customs union but code for a soft Brexit; and Remain.

The blue columns are the distribution of the public, the orange columns are the Remainers and the grey columns are the Leavers.

There are two points to note. First, public opinion is fragmented. None of these options command majority support of the public as a whole; second, crucially, public opinion at this point is polarised.

The most popular opinion among Leavers is leaving without a deal. The most popular option among Remainers is to remain inside the EU, unsurprisingly.

You could see how coming up with a compromise that was going to satisfy public opinion was not necessarily going to be easy.

Let us consider what the public were expecting by this stage. The short answer is not a lot. ORB asked people: Do you agree or disagree that the Prime Minister will get the right deal for Britain in the Brexit negotiations? This question is looking at how expectations are developing as the Brexit process emerges.

There is a period when more people agree than disagree. It is bounded by two events. The first event is the Lancaster House speech of January 2017 in which the Prime Minister first laid out her understanding of what Brexit should mean.

In the wake of that, the public said that it sounds as though she has some idea of what she is on about and public confidence in the government’s handling of Brexit rose. But then, of course, the Prime Minister a few months later went for what was a wild walk in the woods of Wales and came back with a general election, which she failed to win, and immediately public opinion in her ability to come back with a Brexit deal that they might like was diminished.

It continues to decline thereafter. The Chequers agreement knocked public confidence that she is going to come back with something that they want – and it has not recovered since.

A YouGov poll asked how people thought that the government was handling the process. Things improved in the wake of Lancaster House before the election; and after the election, it has become worse and worse.

Public confidence in who was negotiating and expectations of what they were going to obtain have been diminishing ever since June 2017; but note that the Chequers compromise, which I have shown you was unpopular, served to diminish further expectations and confidence. There was a warning there.

What were the public expecting in terms of immigration and the economy? So far as immigration is concerned, this is a question being asked of people every month: do you agree or disagree that Britain will have more control over immigration post-Brexit? It continues to be around three in five people who expect the UK to have more control over immigration post-Brexit.

Do you agree or disagree that Britain will be economically better off post-Brexit? This question from ORB has tended to produce a more optimistic perspective on the economic consequences than have some other polls. It is the one that has been going on the longest and that is why I have used it.

In late 2016 or early 2017, more people thought that the economy will be better off post-Brexit than thought it would be worse off. But after June 2017, it becomes 50–50. More recently, however, people have begun to have been more concerned about the economic consequences.

That said, Leavers and Remainers have long since had very different views of what the consequences would be.

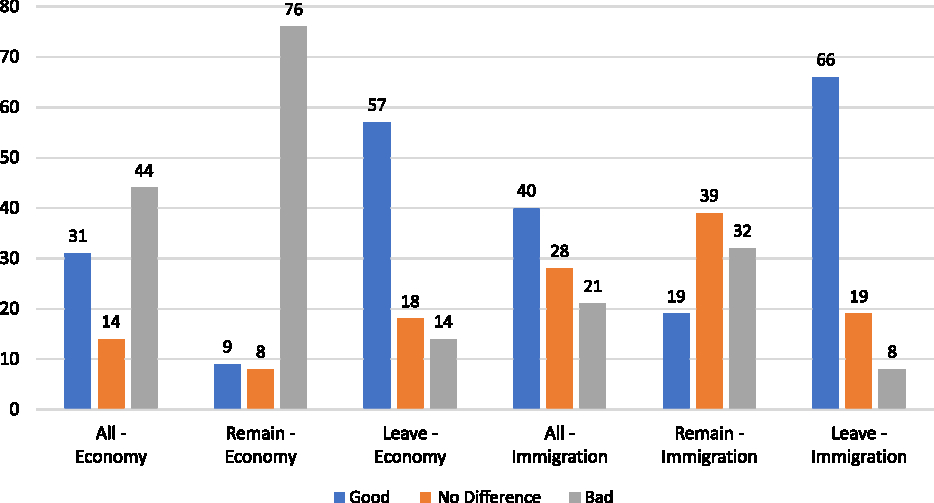

On the left-hand side of Figure 5, you can see what people think about the economic consequences of Brexit. By November 2018, 76% of Remainers think they are bad but 57% of Leavers thought they would be good. Sixty-six per cent of Leavers think that Brexit will be good for immigration, and this poll allows people to define for themselves what “good” meant, and Remainers were none too sure.

Figure 5. Leavers and Remainers have different perceptions.

We not only have polarisation in people’s views about Chequers, but by the time we get to the unveiling of the negotiated agreement, the public are also polarised between those who think that Brexit is going to deliver on immigration, those on the Leave side and those on the Remain side who are concerned about the economic consequences.

Let us now take ourselves to the point of Mrs May’s deal. By now you can see the warning signs. Mrs May’s problems in the last 3 months were already baked into the structure of public opinion by the time the Brexit process had reached November 2018. YouGov asked: do you support or oppose the draft deal? Again, a lot of people don’t know. YouGov had not asked this for a long time but they then asked it again yesterday. No change.

The problem is that the public did not like the deal. Opinium has also been tracking this. Not very many people thought it was going to be good for Britain. Quite a lot of people thought it was going to be bad for Britain. Quite a lot of people were in the middle.

There are no signs since mid-November of increasing public support.

But, once again, Theresa May, remarkably, manages to unite Remainers and Leavers. As in the case of Chequers, they agree it was not a terribly good idea. The Leavers are more sympathetic than the Remainers, but not by very much.

We might not be surprised that the Remainers say this is a bad deal. But given that the Prime Minister is attempting to implement the mandate in the instruction that she feels she was given by the vote in June 2016, it has been an embarrassment that you cannot point to polling evidence that says the people whose instruction you are trying to implement think that this is a good idea. It has always been a weakness in her case.

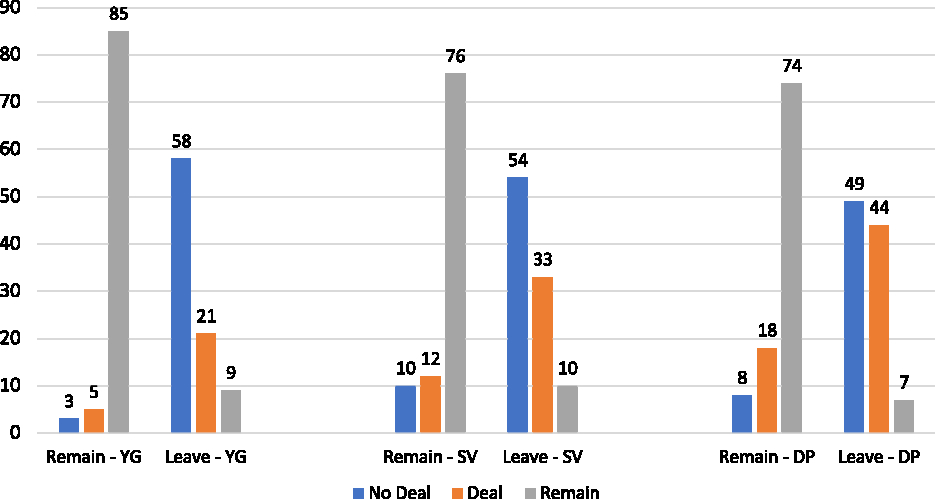

Now although Remainers and Leavers agree it is not good, they do not do so for the same reason. This becomes clear once you start to ask people to choose between No Deal, Deal and Remain. The chart in Figure 6 shows three different polls.

Figure 6. Different priorities.

The left-hand side is from YouGov. Eighty-five per cent of those people who voted Remain still want to remain. The position among the Leavers is consistent across the polling data. At least a half of the Leavers faced with the choice say “No Deal.” Only one in five Leavers say that they prefer Mrs May’s deal.

Public opinion back in September was already polarised between the No Dealers and the Remainers. Mrs May’s compromise has indeed found itself caught between those two positions. Neither the Remainers nor the Leavers are willing to back it.

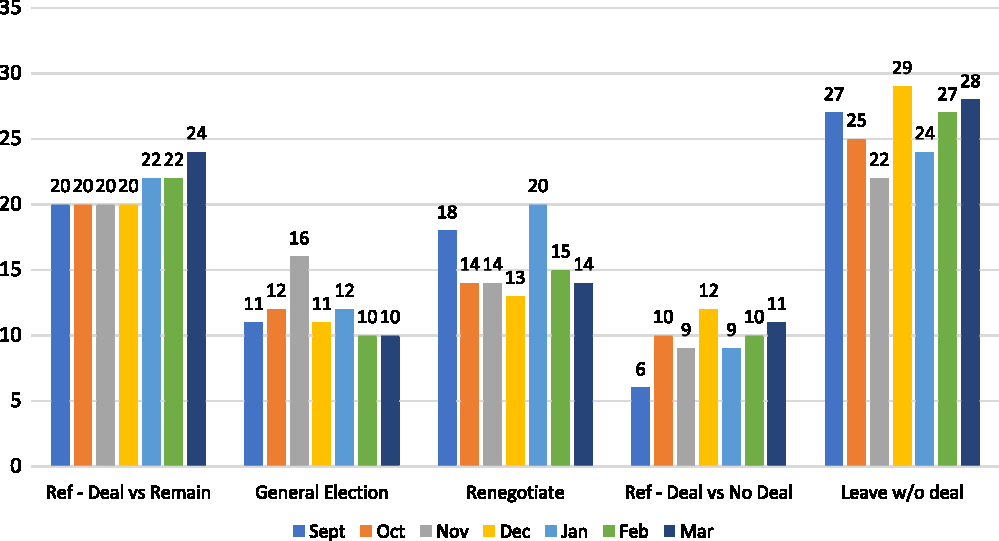

I showed you how public opinion was fragmented back in September. It still is. Data from Opinium is not about the substance of Brexit; it is about the procedure.

In Figure 7, Remain is on the left-hand side and Leave is on the right-hand side. But the left-hand side are those people who say we should have a referendum of the Deal versus Remain. Then we have a general election; then renegotiate the deal, which is what Mrs May eventually did; then a referendum on Deal versus No Deal; and then leave without a deal.

Figure 7. Procedural pluralism.

Notice that no option comes close to being the view on the part of the public as a whole, but notice, too, how the two most popular options are the “referendum deal versus remain” and “leaving without a deal.” So, the polarisation is still there.

It becomes even clearer once you break the public down according to how they voted. The single most popular option among those who voted to remain is to have the referendum of the Deal versus Remain. Even though they are faced with four other procedure options, 47% of Leavers say leave without a deal.

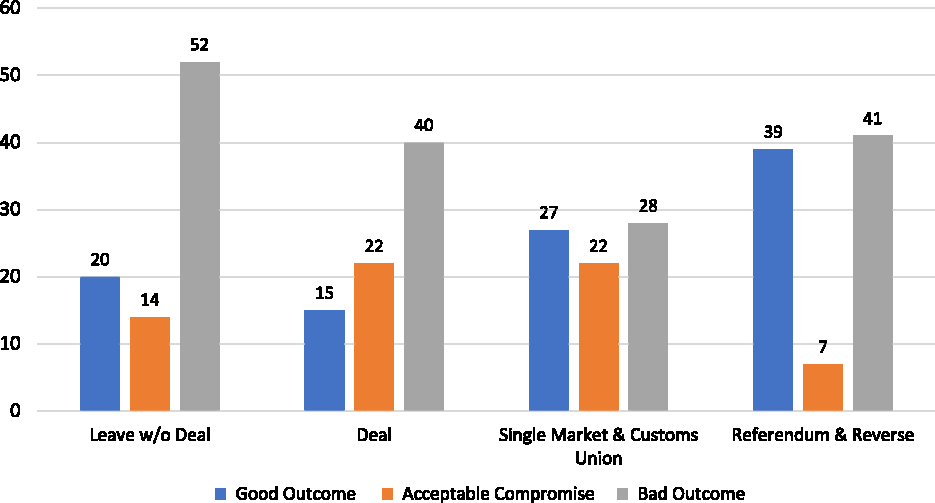

You might want to object at this point. You might want to say you are asking people what their first preference is. What would they be willing to accept? It may not be your first preference. Maybe, we should be looking separately at what people think about these various options. That is what has been done here in Figure 8.

Figure 8. An explicit search for compromise.

Here, we are also giving people the chance to say the option was an acceptable compromise. People could say it would be good or it would be bad; but they can also say it would be acceptable.

Half of the overall public said leaving without a deal was a bad idea. For holding the referendum and reversing Brexit, the single most popular response was that it is a bad idea. Mrs May’s deal does not come out too well, either. Only 37% of people say it is either a good or an acceptable outcome.

For the single market and customs union, around half of the public might be willing to accept it and only 28% say it is a bad outcome.

However, I want to suggest to you that it is not sufficient, if we are going to regard it as something that is an acceptable compromise, for it to be backed by half of the public, if that half of the public comes from only one half of the polarised divide, because when you ask Remainers and Leavers separately about staying inside the single market and the customs union, half of Leavers say this is a bad idea; only around a third of them are willing to put up with it. Soft Brexit is a Remainer’s Brexit; it is not something that bridges the divide and if we go down that path in the wake of the Brexit process, those who are promoting it are already warned.

Survation gave the same people the choice of remain, deal or leave without a deal. The deal is the least popular of those three.

They also asked the same respondents: remain, Norway or leaving without a deal. Norway also emerges as the least popular option.

The danger potentially with the soft Brexit route is that it will face the risk of being a friendless compromise.

The problem is that, having denied the UK public the chance to have their cake and eat it, we have created the circumstances whereby public opinion had the potential to polarise. It has polarised and it is still polarised. The reason why this is so difficult to resolve now is that the House of Commons is doing a brilliant job of reflecting the fact that public opinion is fragmented. They do not like Mrs May’s deal, but they do not like much else otherwise. It is also reflecting the polarisation of public opinion.

It does mean that coming up with something that is going to satisfy people is frankly very difficult. To that extent, at least we can get half of the country’s preferences in public policy, but to get more than that is difficult.

Finally, are we still of the same view as we were in June 2016? It is the question that YouGov has been asking on a regular basis. In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU? Up to and including the June 2017 general election YouGov found slightly more people saying that it was right than wrong. We have obviously changed our mind.

After the general election, typically YouGov found the opposite and, indeed, in the autumn of last year found the lead of wrong over right increasing, although it now seems to have stabilised. It is now consistently getting something like an eight-point majority of wrong over right.

There are quite a few polls out there that ask people: How would you vote if there were to be another referendum? A moving average of the last half-dozen or so polls since the beginning of last year has been consistently showing, certainly since the spring of last year, a small lead for Remain.

For most of last year, it was bouncing round 52/48. By early this year, it had moved to 54/46 but it has moved back down again. It is currently running at 53/47. So, it is there, but it is not dramatic.

But why has it occurred? Is this evidence that some Leave voters have changed their minds and are therefore hanging on to the outcome of the 2016 election as still the will of the majority of the electorate is dubious? It is more complicated than that.

Perhaps by now you should not be surprised, given how polarised I have shown you public opinion is about the deal, about the procedures and about the consequences of Brexit. Few Remain voters and few Leave voters have changed their minds.

Looking at the average of the six polls that have asked people both how they voted in 2016 and what they would do now, 85% of Remain voters would vote exactly the same way; and 82% of Leave voters would vote exactly the same way.

The idea that the Leave voters are more likely to switch to Remain than Remain are to Leave is not the case.

The Leave vote looks a little softer, not least because some of them say, “Do you want me to go out and tell you again that I want to leave the EU? I told you last time. I am not going to bother again.”

Anyway, the Leave vote looks a little softer, but that is it. The reason for the most part why the polls in aggregate show a shift towards Remain, narrow though it is, even though most people have not changed their minds, is because of the view of those who did not vote in 2016. Some of them could not, but that is by no means all of them.

Notice that if you now ask them what they think, they are at least 2–1 in favour of Remain. So, it is not so much the case that the public have changed their minds, but some people out there have made up their minds rather late in the day.

This, if anything, is the group whose opinion has shifted to a degree. I can now track this going through the surveys that I have been doing. I can track how those who abstained said they would vote.

Back in September 2016, they were more pro-Remain than they were pro-Leave but not dramatically so. By the time of my most recent survey, which was last summer, like all the opinion polls, it was much more Remain than Leave. So, this is the group that has shifted, but they are the people who were not involved 2½ years ago.

I am inevitably concluding that there are some important questions to be asked about the success of the Brexit process so far. But there are issues that arise, I am suggesting to you, as a result of the way in which there has been a clash between the structure of British public opinion since June 2016 and the process through which Brexit had to be negotiated. This is because it was not something that lay within the ability of the UK state alone to deliver. Although the EU members are throwing their hands up in horror and saying that it is not their fault, the structure of the process is the EU’s fault. One can argue, I think, that the structure of the process has contributed significantly to why we are where we are.

It was never going to be easy to satisfy most voters once free movement and free trade in combination was off the table and, against that backdrop, finding a compromise that can bridge the divide, that can keep a majority of the British public happy, is proving very difficult.

Along the way, that has helped to ensure that we have become more pessimistic about the Brexit process and what it is going to deliver, but that has not made many people change their minds. “Please,” say the Leavers, “Give us what we voted for. We just do not think that, between you, you are providing it.” The Remainers say it is a bad idea, and they have not changed their minds. That is the difficulty that we face.

The Chairman: Thank you, Sir John. I thought you put together an argument for us about why it was never going to work. But let us have some questions from the people here.

Mr R. L. Macdonald, M.S.P.: I am member of the Scottish Parliament and I have a question rather than seeking to impose my own views on the matter.

In describing the shift in public opinion, such as it is, that you have been able to detect, you said that the shift is most notable among abstainers.

That then becomes a very important question. Have these people abstained because they are not interested in ever voting on anything or because they are not enfranchised to vote in referendums in Europe? In either case, it makes no difference to the prospects going forward. Or is it simply people who have reached voting age in the last 2½ years or who have otherwise become engaged with public policy in a way they were not before? In this case, what they think does matter.

Prof Curtice: The best answer that I can give you is that 57% of them are aged 35 and under. They are disproportionately the youngest section of our population and although the turnout in the referendum was relatively high by the standards of recent general elections, it still was no more than 71%. So, in part at least, this is the fact that, as everybody knows, younger people are much more likely to vote Remain than older voters, so we should therefore not be surprised that the abstainers are much more pro-Remain.

But, as I suggested to you, it is not just a question that they were always pro-Remain, but whether they seem to have moved in that direction.

I am tracking through a series that is not particularly influenced by those who have come into the electorate since the age of 18; but, yes, there is some of that going on, but it is not enough to drive it.

Demographically, this is a group that was always likely to be more pro-Remain but they probably have become more pro-Remain than they once were. But it does mean that those on the Remain side, who are waving the flag for the people’s vote in the confident expectation that the country would vote differently second time around, are perhaps resting their hopes on a somewhat more fragile instrument than they realise.

Maybe these people will come out next time and, as a result, we would now narrowly vote in favour of Remain. But who knows? I think it is sufficiently close that the quality of the campaign would be crucial and that means those on the Remain side must have an argument about immigration. They had no argument about immigration last time. You must convince people – because this was the other weakness in the Remain campaign – how being inside the EU will make this country better off. Although there was a lot of pessimism about the consequences of leaving, there was also a lot of pessimism about the consequences of staying.

A fundamental difference between the position now and back in 1975, when two-thirds of the public were persuaded to vote in favour, is that back in 1975 it was easy to portray the EU as a successful economic institution. Those days are over in the wake of the Eurozone crisis.

The Chairman (Ms. Louise Pryor, F.I.A. (from London)): Has there been any change in how people think of the importance of Brexit compared with running the country – for want of a better phrase?

Prof Curtice: The polls have asked people what the most important issue is; the polls have asked people about what they have read in the news this week. Brexit, Brexit, Brexit!

The other thing to understand is, on both sides of the argument, not only are people polarised but these views for many people are intensely held.

One of the concepts, which is borrowed from social psychology and that we have in clinical science and electoral studies, is called “party identification.” It is the idea that somebody would say, “I am Labour” or “I am a Nationalist” or whatever. It is the idea that people identify with a political party; they have an emotional attachment such that it does not matter whether it puts up a monkey as a candidate, they will vote for it. They have that tribal loyalty.

One of the things that my profession has been writing about for the past 30 years is the decline of party identification, that voters no longer have this emotional attachment, and this is one of the reasons why voters are less likely to go out and vote. We have been bemoaning the fact that there has been this disengagement.

Around 10% of voters for the past 30 years or so have said strong Labour or strong Conservative. Ask the same questions about Remainers or Leavers and 40% of people say that they are either a strong Remainer or a strong Leaver. It is an issue where we feel intensely on both sides.

By the way, if anybody thinks that the Leavers are the emotional folk and the Remainers are the rational folk, let me disabuse you straight away. Remainers are more emotionally committed to their side of the argument than are Leavers to their side. The loss from leaving EU is felt intensely by many people on the Remain side. It is a reason why, if we were to ever have another referendum on this subject, probably we would get a higher turnout. Whether we would reach the 85% of the Scottish independence referendum, I am not sure. But maybe we would get back up to the high 70s that we used to get in general elections.

The level of engagement within the public that used to generate that kind of turnout in general elections is now there on this issue.

Mr H. Walpole, F.I.A.: Is this an analysis our politicians have access to?

Prof Curtice: Yes. I run a website called Whatukthinks.org/EU. Most of this material is there. Indeed, I gave a presentation on the second half of what I talked about this evening in the Palace of Westminster just last week. So yes, they do. I have spoken to those on both sides of the argument and there is at least some understanding; but there is selective perception.

We get an opinion poll on Sunday asking a somewhat loaded question that seemed to show an increase in support for leaving without a deal, but they had not asked the same questions that they had asked last time. They had 44% of people in favour, and more people in favour of no deal than not. That is what some Leavers will quote every time you ask them what the public thinks about no deal, ignoring all the other evidence I have shown you this evening.

Equally, every time they get an opinion poll that is 55% or 56% Remain, the Remainers are out there on the Twittersphere desperate to tell everybody about this.

So, the information is there, but because of the environment within which we are operating, those of us who are trying to provide evidence impartially are frankly in much the same dilemma as the Prime Minister, which is that people want to believe what they want to believe, and those of us are sitting in the middle are not sitting in a very comfortable place. So the evidence is often ignored.

The Chairman: We have had a question from Graham Pilmoor over Twitter: Are you able to quantify the impact of fake news in the referendum?

Prof Curtice: No. I will expand slightly. Fake news is in the eye of the beholder. That was evidenced by the argument about the £350 million. If you are a Remainer, you say that was a lie. You say, “Look at the net contribution,” and the net contribution is less than £250 million a week.

If you are a Leaver, it is the truth because for Leavers what matters is the fact that the fate of that £350 million was no longer the consequence of a sovereign-deficient decision by the UK. For them what matters is what we pay in, because what we get back is decided by the EU not by the UK.

Remainers will insist that that was fake news. Leavers will tell you no: that is the truth. It is clear that both sides were not always entirely accurate in their forecast of how the Brexit process would play out.

Mr H. R. D. Taylor, F.F.A.: There is quite a lot of talk about the potential for a people’s vote, for a further referendum.

Is it conceivable that there could be agreement among another group, presumably those in the House of Commons, on the questions, a timescale for presenting them and, most importantly, the factual basis on which people were to be given the option to vote for a range of options? It seems to me that there is such polarisation in views about what the facts are that that in itself would be difficult to achieve.

Prof Curtice: Yes, absolutely. I am sceptical about the ideas of truth commissions and people responsible for marking campaigning homework. The way in which campaigning homework should be marked is through the critical interplay of the two sides. That is, if one side tells a lie, the other side should be capable of pointing it out and convincing the electorate that that is the case.

We must rely on a democratic dialogue in order to identify truth from falsehood. The fear of the £350 million was a classic case where, once you looked behind it, the point that you are exposing was different conceptions about what the UK’s relationship should be with the EU.

I have three things to say about the people’s vote. The first is, as I have already shown you with some of the data, it is a Remainer project. I think the people’s vote campaign has failed seriously to pivot. We talk about the Prime Minister not pivoting, equally the people’s vote campaign has felt that the moment Theresa May’s deal went down should have been the moment at which the people’s vote campaign said, “Prime Minister, those MPs will not let your deal go through. We think you should be allowed to put your deal before the public.”

They should have made a much more deliberate attempt to persuade Leavers. The so-called “Kyle Wilson amendment” that we might or might not see at some point is clever because it says exactly that. We will let your deal go through the House of Commons in the same way as the Alternative Vote went through the House of Commons, but then we will have to have a referendum to see whether that is accepted or not. Whether or not that will happen, who knows? That is the second point.

The third point to make is that the kind of referendum we can hold now is circumscribed because we can only hold a referendum if we obtain an extension for the Article 50 process. We can obtain an extension of the Article 50 process only if the EU agrees. It is not in the EU’s interest to allow a referendum where the outcome could potentially be worse from their point of view than what is currently on the table, that is, Mrs May’s deal. It is in the EU’s interest to facilitate any referendum the outcome of which might be from their point of view something better than Mrs May’s deal, and from their point of view the best outcome is for us to change our minds.

Therefore, a referendum in which no deal is on the ballot paper is, in my view, now inconceivable. But putting Remain on the ballot paper, the EU will love that, and so a referendum on Mrs May’s deal versus Remain is probably the only option that is available.

Most people would accept that it will take between 5 and 6 months, so we are probably now talking about September or October. That is assuming that we will be able to do it now, so it does involve a long extension, and it does involve us getting involved in the European elections. But at the moment, the votes are not there inside the House of Commons.

I think that we are about to see a battle between the Common Market 2.0 and the people’s vote and seeing whether either of them can command a majority inside the House of Commons. It does not look as though the votes are there for a referendum at the moment, but they might be later on in certain circumstances.

But there are many different versions of Common Market 2.0, and whether or not the various tribes and scribes of Common Market 2.0 can come to an agreement so they might be able to get a majority in the House of Commons is going to be something to watch in the next few days.

Mr A. Wightman, M.S.P.: My sister lives in Switzerland. She votes in referendums all the time. Are referendums a good idea?

Prof Curtice: In my view, there are certain questions that you probably do have to determine by having a public vote. The first category is indeed decisions about who should be sovereign and with whom are you willing to share sovereignty?

Insofar as any set of political arrangements means that some people, whom we will loosely call “lawmakers,” have the ability to set the rules and regulations by which the rest of us are expected to live, and also can invoke penalties upon us if we were to fail to do so, then our willingness to accept that authority has to lie with public opinion.

If the public do not regard those who have that authority as being legitimate, then we have a problem. That is why I would argue the only way you can legitimately solve the question of whether Scotland should be an independent country or should be a part of the UK is through a referendum because with that you ascertain the consent of the people.

I think it is the same issue with the EU. It is whether we were willing to allow Brussels to be part of our law-making process. It has long been known there has been serious doubt within the British public about the legitimacy of that process.

I do not think I am willing to allow politicians to decide the process by which they are elected. I think holding the referendum on the Alternative Vote was fine and I think, in general, that decisions about the electoral system, and primary legislature, should also be decided by referendum, otherwise politicians are writing the rules of the game by which they themselves get elected, and they have a vested interest therein.

Beyond that, it is for you to decide but I do not think that there is the same necessity beyond those two things. I am acknowledging what I said right at the beginning. The difficulty one could face, and it was there for both the Scottish independence referendum and the EU referendum, is that it is not necessarily within the political state to deliver.

The UK government was never going to agree to come to an agreement with the Scottish government in advance of holding a referendum for people to know, insofar as it is possible to know, what independence might mean.

Equally, the EU was not going to enter negotiations with the UK so that we can find out how good a deal we could get.

Vested interests mean that there is always going to be a constraint on the amount of information available, although it does potentially open up an argument that maybe in both cases we should have been starting off with a two-stage referendum process rather than a one-stage one.

The Chairman: Now we have another question from Twitter. Erin Bargate has asked: If Theresa May asked you for advice, what would you tell her?

Prof Curtice: I understand where she is at and given where she is at now, she frankly has no choice. Theresa May is, above all, trying to keep her party together, difficult though that is.

I think that she is aware that if she pivots towards No Deal or she pivots towards a soft Brexit, her party will split. After last night, she is minded to have another go, although John Bercow is saying she might not be allowed to have another go, which does mean that she may not get a chance. But she is trying to keep her party together.

Should she have had the sense to try to negotiate a broader party compromise? She would have still faced the fact that much of her party is deeply divided on this subject, and whether or not she could keep it together if she had, from the beginning, gone and talked to Jeremy Corbyn and Kier Starmer, and so on, and said, “Can we come to an agreement?” It would be better through the House of Commons, but would she survive the experience?

One can see a pathway in the problems she faces by which she might be able to get a Brexit deal through the House of Commons, but she would probably become the Ramsay MacDonald of her party along the way. Above all, Theresa May is a Conservative.

For those of you who want to know, the amendment that means that the House of Commons is opposed to No Deal in all circumstances has been passed by four votes.

So, the government was coming out in favour of No Deal but the government’s motion simply said, “No deal on 29 March” and still left open the possibility that we might crash out on 22 May or some other point in the future. The House of Commons very narrowly has voted to rule out no deal entirely. That will not make Theresa May’s job any easier.

The Chairman: I do not think that it will.

Mrs I. M. Paterson, F.F.A.: My question is about something you asked at the beginning. What is the outcome of a referendum? When can we say it is clear? If one group, the “yes” group, say 55% and 45% does not want what the referendum is about, is that a clear decision? Or is it a divisive decision and you need to have a second question?

If you have not, what should be the rules for taking action from a referendum?

Prof Curtice: I will make two points. The first is that, in my view, if you hold a referendum and you discover that a majority no longer accept the institutional arrangements that govern a country, it is difficult to ignore that.

There are lots of people saying, “It’s only 52%.” Can I remind people of the rules of the referendum of March 1979 when Scotland voted narrowly in favour of creating the Scottish assembly. It was not implemented because there was a 40% rule. Ever since – at least until recently – most people have been saying such rules are a bad idea.

The second point is political. I think that you should not hold a referendum unless you know what the answer is going to be. Referendums are ideally mechanisms for demonstrating a consensus. They are not necessarily a good way of solving an issue on which you are divided.

The Scottish independence referendum failed to answer the question because, although David Cameron thought he knew what the answer was going to be, in fact the answer was not as clear as he expected.

In 2016, Cameron presumed that he could pull off the same trick that Harold Wilson did in 1975 and swing public opinion around, but he did not. And the moment he did not, he was in trouble. Nick Clegg should have known what the answer was going to be to the Alternative Vote referendum before he did it as well.

The classic case of a referendum that was demonstrating existing consensus was the Scottish devolution referendum of 1997. That said, let us remember the Welsh assembly referendum of the same date went through very narrowly. For the most part, devolution is now not only much more extensive than it was originally, but the principle of Welsh devolution is no longer argued about. So sometimes narrower outcomes do succeed in generating a concern.

But who knows, maybe eventually somehow or other, if we do manage to get out of the EU, we discover that, much like Norway, it is all right, it works, we have a reasonable relationship. But equally we might still be debating it in 20 years’ time.

The Chairman: Thinking about debating in 20 years’ time, we have time for one succinct question to finish off.

Mr A. J. Rae, F.F.A.: You started at the beginning by stating the difference between a general election and a referendum. You indicated that for questions about who governs, a referendum is a better democratic tool. Is it, however, necessary to have a general election now in advance of any second referendum in order to have a functioning parliament to enact the result of a referendum?

Prof Curtice: There are maybe two points about that. At the moment, going for an early general election looks quite a good idea from Theresa May’s point of view because the Labour Party is falling quite a long way behind and she might do better than she did in June 2017. That said, everybody knows what happened in the June 2017 election campaign.

Do not stop assuming that British general elections are going to produce overall majorities. The electoral geography has changed in such a way that it is now much more difficult for anybody to get a substantial majority. It is no accident that we have had three general elections in a row in which we have either had a hung parliament or a very small majority.

Therefore, one of the problems with holding a general election as a way of trying to resolve the so-called Brexit impasse is that it may not give us an answer. However, the argument in favour is this: were it to be the case that the Labour Party would come out in favour in principle of a second EU referendum, as opposed to what it has done so far, which is to create an extra hurdle that Theresa May has to get past, there is no point having a second referendum. If Theresa May, by some miracle, manages to get a deal through the House of Commons, will that then also make her get it past the electorate? She has to pass both hurdles. If there is no deal, that is it. We are not interested in a second referendum.

Unless the Labour Party were to win an overall majority, or maybe the Labour Party, in combination with the SNP and the Liberal Democrats, would have an overall majority, you could then argue that there was a mandate for holding a second EU referendum and then therefore you would create a legitimacy for holding that instrument. But you might just get a messy answer.

The Chairman: We do not like messy answers but we might be stuck with them. It is time to draw tonight’s event to a close. I should just like to thank you all for your attendance and I should like especially to thank Professor Sir John Curtice for such a fascinating presentation and for answering your very good questions.

I think we have learnt one thing which is do not hold a referendum unless you actually know what the answer is going to be.