1. Introduction

The impetus for our research into this topic was the observation that post-retirement solutions vary significantly from country to country even though the people living in those countries are generally facing the same risks.

There are many complex issues involved in post-retirement solutions: insufficient savings; low bond rates in many countries; lack of financial knowledge; opaque products; changing regulations; varying savings patterns; inconsistent fiduciary liability; short-term political pressure; and the role of the state as a safety net, to highlight just a few. Added to this, the numbers of people involved are vast and growing due to improving longevity; at the end of 2013 more than 570 million people were aged over 65Footnote 1 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2013) and by 2050 this figure is expected to rise to over 1.5 billion (Haub, Reference Harrison and Blake2011).

The issue of not having enough to live on is most likely to be solved by increased savings rates before retirement. The majority of people globally have not saved, and are not saving, enough for their retirement, especially given improving life expectancies (The Defined Ambition Working Party, Reference Twigg2014). While normal retirement ages are edging up in many countries, the pace is generally not enough to offset the increased expected lifespan – the expected time spent in retirement is therefore also increasing. Individuals, and plan sponsors on their behalf, must increase contributions and invest in assets generating returns above inflation in order to aim for a satisfactory target portfolio value by retirement.

1.1. Has Any Market Implemented the Perfect Post-Retirement Solution?

1.1.1. Although this is a common problem, there does not appear to be a common solution. However, as can be seen in Figure 1, there are three main component techniques (annuities, cash lump sums and programmed withdrawals from individual accounts), none of which is individually “perfect”. Solutions are clustered around one (or more) of these three component strategies. Additionally, post-retirement practice is a fiscally sensitive subject which often results in solutions changing with the party political cycle.

Figure 1 The most prevalent options taken in retirement for selected defined contribution markets

1.1.2. Retirement systems are unique to each market, reflecting their history, politics and cultural preferences. In Europe, the starting position for many countries has been that annuities are the appropriate solution for retirees. This is likely based on their similarity with defined benefit (DB) pensions that provide a familiar, predetermined level of income for life. In Latin America, the Chilean pension systemFootnote 2 has been used as a template by many others in the region, and programmed withdrawals have been growing in popularity. While in Asia, lump sum payments are far more common than elsewhere.

1.2. How Much do Individuals Need?

1.2.1. In order to address the issue of running out of funds in retirement, one must first establish how much individuals need in retirement. Funding for retirement generally comes from a combination of sources – the state, corporate and personal pension savings and additional assets. The total level required has already been the subject of much academic research (Munnell et al., Reference Kahneman2011; Hewitt, 2012). The answer depends on a number of factors such as

-

∙ the interest expected to be earned on retained savings;

-

∙ how long an individual will live;

-

∙ the costs of living, including healthcare and long-term care costs where relevant; and

-

∙ the impact of future inflation on these costs.

1.2.2. Studies in the United States have shown individuals need 16 times salary as a retirement account (broadly split 30% state and 70% corporate/personal plus savings) (Hewitt, 2012). However, the reality is that, even for a retiree with over 30 years of contributions, the average defined contribution (DC) account size for those nearing retirement is only around $250,000, which is around five times average final salaryFootnote 3 (Holden et al., 2014). While this may not be a significant issue currently, as DC plans are not the only source of funds for many retiring now, many DB plans are now closed and so DC will be required to play a more important part in future.

1.2.3. In the United Kingdom, many DB plans promised provision of two-thirds of final salary at retirement after 40 years of employment. Using current UK life tables and interest rates, this equates to building up a retirement account of around 12 times final salary (on a single male life, level annuity basis). Many DB plans offered additional guarantees, such as increases with inflation and payments to a spouse following the member’s death. When factoring in these benefits, the equivalent DC pension account may need to be as high as 19 times final salary.

1.2.4. In Australia, the government provides guidance to individuals about how much they need to save into their DC plan in order to attain two different living standards: modest and comfortable. The largest difference between these living standards is the level of “leisure” spending it allows, with a comfortable lifestyle allowing almost three times the amount to be spent per week on this discretionary category compared to those with a modest lifestyle (Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia, 2014). As multiples of salary at retirement, the two standards equate to around seven times salary to cover a modest lifestyle with this rising to almost 13 times in order to provide a comfortable, but still not luxurious, retirement lifestyle (Australian Securities & Investments Commission, 2015). As with the United Kingdom, if inflation and state provisions are factored into the calculation, the required multiple could be as high as 17 times salary for a comfortable lifestyle.

1.2.5. In this paper, it is assumed an individual has a retirement account of 12 times their final salary, and targets a pension income of around 60% of their final salary. This broadly relates to having sufficient savings at the point of retirement, allowing the investigations to focus on the post-retirement issues in isolation.

1.3. Ill Health and Care for the Elderly

With people living longer, the issue of health and long-term care for those living with degenerative diseases becomes more important. In developed countries with ageing populations, healthcare costs can be extreme, particularly in the United States. In addition, around half of US spending on medical costs are privately funded (OECD, Reference Munnell, Golub-Sass and Webb2013). While we do not address this specific issue in this paper, flexibility in the investment solution is imperative in order to deal with the risk of requiring cash at short notice.

2. Influences on Post-Retirement Solution Design

The influences on post-retirement solution design are somewhat different from those affecting pre-retirement. There are some similarities, tax and regulation being the two most obvious, but other factors, such as politics and culture, have far greater impact than in pre-retirement. Additionally, many of these factors are inter-linked. The key factors influencing the shape of post-retirement solutions are as follows:

-

1. Regulation and legislation

-

2. Taxation

-

3. Politics

-

4. Culture and behavioural biases

-

5. The need for simplicity

-

6. Improving life expectancy

-

7. Semi-retirement/phased retirement/flexible retirement trend

-

8. Innovation

-

9. Depth of the market

-

10. The healthcare system

2.1. Regulation and Legislation

2.1.1. Regulation, arguably, has the largest impact on solution design. If individuals are not permitted to invest their retirement savings in certain vehicles or products then there is no opportunity to design alternative strategies that include them. In some markets lump sums (or partial lump sums) are permitted at retirement and, where these are also tax-free or tax-advantageous compared to the alternatives, the take-up is generally high.

2.1.2. Some markets have very prescriptive regulation about the investment vehicles in which post-retirement savings can be invested. For example, a number of European countries, such as Poland, Bulgaria and France dictate that individuals buy an annuity at retirement. In South Africa, individuals invested in provident funds are permitted to take the full benefit in cash; those invested in pension funds can take up to a third of the benefit in cash, with the remainder individuals have to buy an annuity. This has led to a large number of different types of “traditional” annuities and also the development of “Living Annuities”. In reality, Living Annuities are not annuities at all and are legally not allowed to provide any guarantees. They are tax-protected, phased-withdrawal products, that is, investment funds where the retiree decides to drawdown a percentage each month out of his/her fund(s). Legislation limits the annual drawdowns to between 2.5% and 17.5% of the value of capital invested. The level and frequency of income can be typically reviewed annually. South African law regards these products as annuities for tax purposes (National Treasury: Republic of South Africa, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2012). This regulatory allowance has permitted a large range of non-guaranteed products (i.e. no longevity protection) to become the dominant choice for retirees (Association for Savings & Investments SA, 2014).

2.2. Taxation

2.2.1. Closely linked to regulation is taxation policy, which is often more complex after retirement than before. Many tax systems offer incentives in the accumulation stage. However, except in a small number of countries, this is only a deferral until income is drawn in retirement. The overall proportion of income paid in taxes and social security contributions tends to reduce for retirees. Many countries’ tax systems charge retirees a lower tax rate, through additional income allowances, lower income tax rates or both, and reduce or remove the payment of social security contributions (OECD, 2014).

2.2.2. In markets where there are high levels of taxation during employment, such as Scandinavian countries, it is common that the rate of income tax remains high in retirement. The United Kingdom, United States and Australia have very different headline rates of taxation for retirees but, through the tax reliefs offered, the result is similar effective rates. In South Africa and other developing countries, pension income is taxed at a low or zero rate.

2.2.3. Where countries levy high levels of income tax on retirement income it is possible that retirees will underestimate the impact of taxation on their income, compounding the impact of any shortfall in their accumulated wealth at retirement.

2.2.4. If products available to retirees are not tax efficient, they will not be widely used. In Australia, in addition to some regulatory barriers that restrict the availability of annuities, one of the key impediments to the take-up rate is that the initial tax treatment of deferred lifetime annuities is penal compared to that applied to investment earnings on superannuation assets supporting retirement income streams.

2.2.5. In a number of markets, for example, Hong Kong, a cash lump sum can be taken at retirement tax-free. This provides full flexibility to individuals to invest as they want in retirement.

2.3. Politics

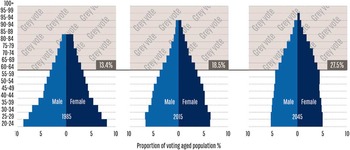

2.3.1. Most pre-retirement systems are far less affected by politics than post-retirement. However, individuals who have retired or are approaching retirement represent increasing population proportions in many countries (Figure 2), and therefore a larger number of votes and an even larger proportion of wealth. Retirees are also generally more engaged with politics and so the rules regarding the amount they have available to spend, or the flexibility they have to spend it, are clearly of significant interest to them.

Figure 2 The world’s population aged over 60 is set to increase in both proportion and influence

2.3.2. Politics can have an overtly detrimental impact on retirement accounts; for example, Argentina and Poland have, in recent times, expropriated individual’s private pension accounts before retirement. At the more paternal end of the scale, politicians in Singapore implemented a government-administered post-retirement annuity fund, called “Central Provident Fund Lifelong Income For the Elderly”.

2.3.3. Retirement savings and spending are very long-term issues; politics, by comparison, is a short-term game. Politicians responsible for pensions and retirement are generally not in position for the long term and therefore may not necessarily have individuals’ long-term best interests in mind. An interesting comparison of the impact of politics can be seen in the case studies of the United Kingdom and Australia. In 2014, after much lobbying to remove the compulsory annuity purchase requirement (particularly due to low bond rates), the UK government announced a complete overhaul of the system. Individuals are now free to take all of their account from retirement in any form (subject to paying income tax). Simultaneously, in Australia, the government’s investigation into pension provision, as part of a wider assessment of the country’s financial system known as the Murray Report, suggested that some or all of an individual’s pension account should be used to buy an annuity (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2014). This has been driven from a concern that people will deplete their pension accounts due to underestimating life expectancy. This could pave the way for deferred annuities to form part of the retirement solution in Australia, where historically there have been regulatory and taxation issues preventing their use. Therefore, while the Australians are potentially moving away from full flexibility, the British are embracing it. Clearly, both cannot be correct in an exclusively financial context.

2.4. Culture and Behavioural Biases

2.4.1. In systems where individuals are free to spend their retirement account as they please, the way in which these assets are used differs widely, often due to culture and historical practice. In Hong Kong, having received the full retirement account in cash at retirement, it is common for individuals to leave the vast majority of this (90%) in bank deposits (Bank Consortium Trust Company Limited, 2009).

2.4.2. In Australia, the Murray Report (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2014) highlighted that behavioural biases are a key reason why account-based pensions and lump sums are popular. Other research (Rocha et al., 2010) has highlighted that Australians have a preference for flexibility and control with their post-retirement savings.

2.4.3. In some cultures that have higher levels of societal solidarity, risk sharing is prevalent. This involves grouping individuals together to pool mortality risk or investment risk (or both). This approach is common in Singapore and the Netherlands. This requires members to “trust” that the amount of pension income they receive will be calculated fairly. It also requires individuals to be committed to the approach for their lifetime. If they are not, individuals can use knowledge about their own expected mortality to enter or leave the pool when it is most advantageous to them, and therefore detrimental to the overall system. In addition, this type of system needs to have an ongoing source of new members to ensure a fair spreading of risk. At times of weak investment results and/or when a cohort survives longer than expected, the system deliberately gives potential for cross-generational subsidy.

2.4.4. Culture also plays an important role in relation to gifting or leaving a legacy to children. In some countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States, retirees expect to gift significant amounts while alive or provide a legacy on their death (Twigg, 2013). Children may also expect to receive these amounts. This has implications for post-retirement solution design: flexibility is required to set aside these amounts; taxation of these amounts needs to be supportive of transfer; and retirees need to be able to calculate how much they will have to live on taking into account these legacy amounts. In other markets, the opposite is true – in many Asian countries, elderly parents are housed and supported by their children. There, the need for savings deep into old age is less pressing.

2.5. The Need for Simplicity

2.5.1. In many studies we reviewed as part of this research, “simplicity” was stated as one of the cornerstones of post-retirement solution design and while we agree with the sentiment behind this idea, we question whether simplicity in itself is the answer or if some straightforward guidelines on suitable solutions for retirees makes more sense.

2.5.2. Studies have shown that there are low levels of financial knowledge in many countries (Lusardi & Mitchell, Reference Aon2014) and it is not clear whether education alone will improve this situation. Coupled with a study (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Driscoll, Gabaix and Laibson2009) that shows cognitive performance declines after age 53, many individuals may not be suitably equipped to be solely responsible for their post-retirement planning, especially when many of these component products can be relatively complex. Given this general low level of financial knowledge, “simple” for the majority of people would mean extremely simple in practice – it may not include multiple asset classes in one product. The simplest investments such as cash or bank accounts are unlikely to result in a better outcome for the majority of individuals trying to plan over an unknown, but long, time horizon with spending needs that are likely to rise with inflation.

2.5.3. Simple could mean “simply communicated”, but the underlying solution is complex. It is certainly possible that this approach can improve the outcome for individuals. However, the risk of this approach is that if something goes “wrong” with an element of the strategy and individuals did not feel that the product was fully communicated to them, they will look for compensation. It is probably more likely in this scenario that there will be a mis-selling scandal.

2.5.4. It is difficult to expect individuals who are heavy users of default products in pre-retirement (and have therefore not had to think about this issue) to suddenly gain the financial knowledge to choose the appropriate investment at retirement. Simple could mean a set of principles that help guide retirees to a suitable post-retirement strategy.

2.6. Improving Life Expectancy

2.6.1. Life expectancy is improving in the majority of countries, as shown in Figure 3. This impacts not only when people expect to retire but the solutions they want and need. Increasing numbers of people expect to semi-retire and these people require flexibility about the amounts that they can take.

Figure 3 Life expectancy is increasing around the world, across all regions

2.6.2. Annuity products offering guaranteed amounts for life can give peace of mind to those concerned that they will not be able to manage their finances for their lifetime (or may live longer than they expect to live). These products are particularly popular in Western Europe where they have been culturally embedded by the design of DC pensions, primarily shaped by the DB plans that preceded them.

2.6.3. Even the recent increases in normal retirement ages in many markets have been too little, and too late, to have much of an impact – the expected time spent in retirement continues to go up, and with it, the expected financial requirements.

2.7. Flexibility in Retirement Trends

Individuals are opting to work more flexibly in retirement (Twigg, 2013), often by choice in order to maintain their lifestyle, enjoyment of the job/working with others or to stay mentally active. This results in a need for post-retirement solutions that allow individuals to take only a portion of their pension initially and to take more later, when fully retired. Products such as traditional annuities offer less flexibility for such a workforce.

2.8. Innovation

2.8.1. Those familiar with the post-retirement market in Australia will know that one of the biggest hurdles that it has faced in recent years in relation to innovation has been the impact of regulation. This was highlighted by Rice Warner (Reference Okunev2014), a specialist research firm, in their analysis of the likely changes as a result of the final report of the Financial Systems Inquiry which stated that, without supportive regulation, providers would not innovate. Similarly in the United States, rules were changed in July 2014 (US Department of the Treasury, 2014) to allow longevity annuities to be accessed by the 401(k) and individual retirement account markets. An issue remains about whether individuals will buy these products (because Americans have been culturally averse to tying up their capital in this way) but the change will likely result in more innovation in post-retirement design.

2.8.2. Another innovative approach we discussed earlier is mortality pooling. We observe that this is a topic currently gathering interest in Australia.

2.9. Depth of the Market

It is difficult to deliver scalable and effective post-retirement solutions unless there is an existing market or instruments with which to create products. In Australia, the annuity market has been small relative to many other countries – Australia’s annuity market is only around 0.3% of gross domestic product (GDP), compared with 28.8% in Japan, 15.4% in the United States and more than 40% of GDP in some European countries (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2014), but this has been as a result of a culture set against using insurance products in post-retirement and regulation/taxation that has made some of these products disadvantageous. This may change, however, if a post-retirement default which incorporates longevity protection as one of the minimum features is required following the Murray Report (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2014).

2.10. The Healthcare System

While it is not the focus of this paper, it would be remiss not to cover the impact of health on the design of post-retirement products. In a number of countries, in particular the United States, given the size of the costs involved, poor health in old age is a significant concern because the State does not (fully) pay for healthcare. This means that unexpected ill health, especially long-term or recurring ill health, can significantly impact savings. Ways to manage this risk include insuring against the risk or setting aside an amount for this type of “tail risk”. However, as with all forms of insurance, there is a cost for both approaches that results in lower ongoing income.

2.11. Future impact of the Influences on Post-Retirement Solution Design

For the majority of these influences, relatively little can be done by corporations, individuals or asset managers to manage them. However, in markets where DC is starting to mature, we expect there to be pressure towards a more institutional approach to post-retirement than has historically been then case. This is likely to result in changes to regulation, taxation, culture, fees and governance.

3. What do Individuals Need From Post-Retirement Solutions?

In this section, we identify the key criteria by which to evaluate the various post-retirement options available to individuals. Then we evaluate whether the solutions currently available can provide the necessary income over the expected lifetime of an individual. In order to identify the criteria, it is first imperative to identify the risks that individuals face in retirement, which in turn can provide a list of features that meet the needs (although not necessarily the wants) of individuals.

3.1. The Four Key Risks in Post-Retirement

3.1.1. There are four key areas of uncertainty in retirement income provision:

-

1. Investment – the risk of earning less than expected on the investment account. This includes both insufficient growth net of fees as well as large losses near the start of retirement (sequencing risk).

-

2. Longevity – the risk of living longer than expected.

-

3. Consumption – the risk of underestimating the amount of goods and services needed in retirement.

-

4. Inflation – the risk of unforeseen price increases of those goods and services. This covers both general increases in inflation of the goods and services as well as spikes in inflation.

3.1.2. The risks here are of actual experience turning out to be different from that expected. Note that these are distinct from the significant risk in pre-retirement of not amassing sufficient savings. Figure 4 demonstrates how each of these risks can be further broken down into more specific risks.

Figure 4 The specific risks faced in retirement

3.2. Who Bears the Risks?

3.2.1. In a DB system, the plan sponsor retains the longevity and investment risks. If the pensions in payment are linked to inflation, that risk is also covered, at least partially (inflation-linked increases in payments are often capped and reviewed annually so do not react to sudden increases in prices). The individual generally retains the consumption risk, however, meaning that they may need to spend more than their pension income. Other insurance products are available to cover some of these contingency costs, such as healthcare or asset replacement/repair expenses.

3.2.2. DB plans have to hold sufficient assets to meet the expected liabilities when they fall due, with the ratio of assets to liabilities being referred to as the funding level. Due to the large number of individuals covered, the longevity risks are pooled and are collectively more predictable. An open operational plan has inflows from workers and outflows to retirees, and so short-term investment returns are also smoothed over time. Under this system, those retirees who live longest are effectively subsidised by those who pass away earlier than expected, and benefit payments are independent of investment returns in their size and durability. In a DC system, each individual, in effect, has their own funding level. However, in the absence of pooling of investment and longevity risk, the variability in these factors has a much bigger impact on that individual’s actual experience.

3.3. Quantifying the Risks

3.3.1. Multiple dynamics can influence the importance of these risks and the impact of these will change as an individual ages. In order to quantify the sensitivity to each, our methodology compares the effects of a marginal change in each factor on the overall cost of retirement for an individual.

3.3.2. In the case of longevity, the focus is on the additional cost associated with living for longer than expected. In the case of investment returns, the risk is of underperforming expectations. For inflation, the risk is that prices rise more quickly than expected. Consumption is the one variable here that a retiree can control, to an extent, and therefore it has been excluded from our analysis. Naturally, setting and adhering to realistic budgets in retirement will go a long way to controlling consumption levels.

3.3.3. Figure 5 illustrates the factor sensitivity at each age (i.e. the impact of a small change to each of these key variables). Early in retirement, the risk of not achieving sufficient returns is the major factor, as there is still a significant period of time over which to grow the assets. The threat from inflation is also at its highest early on for the same reason – there is a long period of time over which the uncertainty associated can manifest itself. Longevity risk starts out relatively insignificant, due to the high probability of survival through the early years. However, this risk grows quickly as the individual ages, reflecting the fact that longevity is self-fulfilling (i.e. the probability of reaching age 90 is much higher for an 89 years old than for a 60 years old).

Figure 5 Sensitivity to longevity risk increases through retirement

3.3.4. This insight can help focus a post-retirement solution on the appropriate risk at each stage of retirement. When the account is largest, generating strong real investment returns with limited bad surprises will have the biggest impact. As the retiree ages, and withdraws pension income from the account, protecting against the risk of outliving his savings should be the primary focus.

3.3.5. In addition to the relative importance of each of the risks, one should also consider the capacity of a retiree to take risk. This is likely to be a function of the size of the overall retirement account and the ability of the retiree to deal with unexpected circumstances. If the retiree is mentally capable and has a large, liquid retirement account, they will be more able to cope with sudden illness requiring medical care or a problem with his housing or care for example. However, as they get older, they are also more likely to suffer from dementia (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Driscoll, Gabaix and Laibson2009; Alzheimer’s Society, n.d.) and therefore may be less likely to be able to make a decision regarding his future investments. For this reason, it may make sense to take decisions regarding longevity protection earlier in retirement, rather than when dementia starts (e.g. from age 80 or 85) even though this may not seem an important issue at the time.

3.4. Heuristics to Manage Post-Retirement Complexity

3.4.1. In post-retirement, individuals have some challenging decisions to make – they must decide how best to make their assets last for an unspecified, but probably long, period. They are unsure what return they will receive from their assets, what they will need to purchase, how inflation will impact the cost of the things they will need to purchase, whether they will become ill and need long-term care, or for how long they will live. There have been many studies showing that the human brain is not well equipped to deal with uncertainty. The most famous recent work on this is by the Nobel Prize winner Dr Daniel Kahneman (Reference Haub2011) who shows that humans often make errors even with relatively simple statistical calculations and so simple “rules-of-thumb” (or heuristics) are created to deal with this uncertainty. Another psychologist, Gerd Gigerenzer (Reference Finke, Pfau and Blanchett2014), argues that individuals need to have an “adaptive toolbox” and then these type of heuristics can be used to make more accurate decisions. The quality of these heuristics makes a big difference to the outcome experienced.

3.4.2. For example, one might consider the US post-retirement rule-of-thumb “The 4 Percent Rule” for withdrawal levels in retirement. As this figure appears reasonable on the surface, many regard this as a suitable heuristic. However, recent research (Finke et al., 2013) has shown that this is likely to be inappropriate when bond yields are low because the assets (if invested heavily in bonds) will not deliver anywhere close to this level of yield. A better, if somewhat less captivating, heuristic might be “If inflation is higher than Y and bond yields are lower than X, I can only draw Z% p.a. from my portfolio”.

Given the high level of uncertainty in post-retirement, there are several options:

-

1. help individuals by providing some “smarter” heuristics about what to invest in, how much to withdraw and when their money is likely to run out; and/or

-

2. develop principles to which post-retirement options should adhere, making these options suitable for most people (but unlikely to be suitable for all, as is the case with pre-retirement defaults).

In relation to the first point, we analyse different investment approaches and drawdown amounts, overlaid with how long people are expected to live to develop some smarter heuristics. Section 5 addresses principles for a successful post-retirement solution.

3.5. When Will the Money Run Out? Developing Smart Heuristics

3.5.1. The uncertainty involved in post-retirement spending needs is so great that any rules-of-thumb should be taken with a sizeable pinch of salt. Our analysis, shown in Figures 6–11, displays the “coverage” levels expected through retirement. This ratio divides the available account by the most recent annual pension withdrawn, to get an approximation of the number of years’ income remaining in the account. We then compare this to the expected future lifetime at each age. With each additional year of life, the expected time remaining reduces by less than 1 year. For example, a 65-year-old man in the United Kingdom can expect to live for around 17 years, to age 82. An 80-year-old man has, on average, around 8 years remaining, taking him to 88 (Office for National Statistics, 2012).

Figure 6 Cash alone is insufficient

Figure 7 A pure equity portfolio takes significant short-term risk

Figure 8 A more balanced portfolio reduces the tail risks

Figure 9 A higher consumption strategy leads to ruin a lot earlier

Figure 10 Being healthier is likely to lead to a longer (and more expensive) retirement

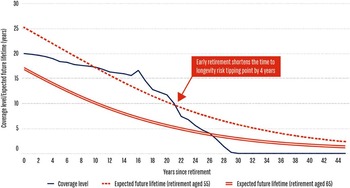

Figure 11 Early retirement increases the chances of outliving your money significantly

3.5.2. By examining the difference between the coverage ratio and expected future lifetime, we can look at the sufficiency of account-based retirement strategies for a variety of investment strategies. In our examples, we have started with a retirement account of around 12× final salary, and a replacement ratio of around 60%, as per the typical target levels in section 1. This gives a starting coverage level of 20× final salary. We acknowledge that this level of savings is relatively high compared to typical account balances at the present time. As DC systems mature, this savings gap is expected to narrow. As noted in section 1, the issue of savings sufficiency at point of retirement can only be dealt with in the accumulation stage, or by substantially delaying retirement.

3.5.3. Figures 6–11 compare the coverage ratio and expected lifetime. Where the coverage range median falls below the expected lifetime line, this can be thought of as the tipping point after which the odds of running out of money are against the retiree. Figure 6 demonstrates that, on this basis, cash alone is likely to be insufficient. After the median reaches the tipping point at age 81, the account is likely to be depleted after only a further 6–7 years. The result is the portfolio provides hardly any protection against the risk of living even slightly longer than expected.

3.5.4. Figure 7 assumes the account is fully invested in equity markets, and the variability in outcomes illustrated through the height of the bars. This study uses actual market data from the past 60 years as a basis, a period when equity markets have generally performed well over medium-long terms but also includes some severe market crashes. Although the intersection tipping point is far later than with cash, the impact of sequencing risk is shown in the lower tail of the ranges in the early years after retirement. Investing is path-dependent and it would be psychologically difficult to continue to pursue the full equity strategy having had a significant shock in those early years of retirement.

3.5.5. Figure 8 shows the impact of a more balanced investment strategy, in this case a 50/50 equity/bond mix. Both non-cash strategies have significant upside potential to reward the additional downside risk. Tolerances for this will vary between individuals, and we suggest that the more balanced portfolio gives a more comfortable set of potential results, when looking at progression of the coverage ratio.

3.5.6. Investment strategy is not the only variable involved. In Figures 9–11, we show the impact on the coverage-versus-lifetime progressions of:

-

a. taking a replacement ratio of 80% instead of 60% (Figure 9),

-

b. being significantly healthier than expected (Figure 10),

-

c. retiring at age 55 rather than 65 (Figure 11).

In Figure 9 it can be seen that increasing the regular withdrawals has the effect of reducing the starting coverage level from 20× to 15×. In some cases, exceptionally strong investment performance can make up the balance, but the median coverage levels are consistently below the expected future lifetime. The odds are tilted in favour of the portfolio expiring before the member. In Figure 10, the portfolio investment returns have not changed, but the expected future lifetime at each age is slightly higher. Since the retiree is healthier, there is a lower probability of death each year, and the intersection with the coverage ratio is therefore earlier in his lifetime. Figure 11 examines the impact of early retirement on the chances of outliving the retirement account. The analysis ignores the fact that, with 10 years’ less savings, the individual is less likely to have saved 12× final salary. Moreover, the significantly lower mortality experienced by a 55 years old, as compared to a 65 years old, has a huge impact on the chances of running out of money before dying.

3.5.7. Many studies, including by the Institute and Faculty Defined Ambition Working Party, highlighted that members have not saved enough for their retirement (Okunev, 2010). Given this shortfall in account sizes, and increasing life expectancy, members are likely to need growth assets for as long as possible because they cannot afford to be overly conservative with their investment approach. As shown in Figures 6–8, this continues to be true as people move into retirement, in order to improve the chances of their account lasting their lifetime.

3.6. Primary and Secondary Criteria Against Which to Evaluate Post-Retirement Solutions

3.6.1. We identify key criteria that individuals should use to judge the effectiveness of a post-retirement product and propose that these should be split into primary and secondary considerations. The primary criteria are arguably more important than the secondary criteria. It is also possible to consider primary criteria relating to “needs” and secondary criteria relating to “wants”.

3.6.2. Primary criteria (needs)

-

1. Reliable protection against longevity risk.

-

2. Stable, real investment returns, net of all fees and costs:

-

a. Investments that provide long-term growth.

-

b. Investments that do not exhibit significant interim losses, particularly when the account is at its largest.

-

-

3. Inflation protection:

-

a. Protection against rises in inflation of the goods and services required in retirement

-

b. Protection against spikes in inflation

-

-

4. Flexibility to adapt to changing requirements.

3.6.3. Secondary criteria (wants)

-

1. Predictability and dependability of the income stream.

-

2. Legacy benefits, such as residual value on early death.

-

3. Simplicity in implementation and communication of outcomes.

-

4. Adequacy of income stream affordable by the accumulated account.

3.6.4. Undoubtedly, a number of these factors conflict with each other (e.g. predictability versus flexibility) and it is difficult as a result to rank them in order of importance. As with many investment decisions for individuals, it is a balance of these factors that is most likely to be most effective.

4. Models of Post-retirement Provision

This is not a new problem, and various solutions have been implemented around the world. These can be classified into three main components, and hybrids thereof.

4.1. The Core Components

There are principally three models of post-retirement income provision which can be delivered inside a DC plan, or outside:

-

∙ Cash lump sum, with no conditions placed upon its use.

-

∙ Investment accounts that provide non-guaranteed income by making systematic withdrawals or from “natural” income. This type can also include:

-

o Post-retirement lifecycle/through retirement target date strategies/reverse target date funds (also called liquidation date funds).

-

o Programmed withdrawal strategies and managed pay-out funds.

-

-

∙ Longevity protection, including lifetime annuities, deferred annuities and risk pooling.

4.2. Hybrid or Combination Options

4.2.1. It is possible (and very common) to create solutions that blend these three components in order to retain their advantages and reduce the disadvantages. Examples of hybrid strategies are:

-

∙ Systematic/agreed withdrawals for a fixed period and a deferred annuity. This aims to provide a non-guaranteed variable amount until assets run out (or death) and an annuity that would pay a fixed amount from, say, age 80 or 85.

-

∙ Capital-protected products including Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefits (GMWB), that is, an annuity with an option to ensure that the original amount invested is the minimum amount that is paid out over the lifetime of the contract.

-

∙ Annuity and/or GMWB to pay for fixed living costs and a managed pay-out fund to cover variable expenses. This would provide an amount guaranteed for life and access to capital from the managed pay-out fund should the individual need it.

-

∙ Variable annuity products to provide a guaranteed income stream for life for a portion of the amount invested and also an increase (or decrease) in the capital amount through market movements.

4.2.2. While many of these hybrids provide more advantages than the single products outlined earlier, they also bring with them added complexity and often a lack of transparency in pricing.

4.2.3. The recent Financial System Inquiry report in Australia (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2014) recommended that a default post-retirement option (called a Comprehensive Income Product for Retirement) should have multiple features covering income, longevity protection and flexibility. A Which? report in the United Kingdom (Harrison & Blake, Reference Gigerenzer2014) also recommended that a post-retirement product to be used in auto-enrolment should incorporate similar features. In the United States, there has been little guidance regarding the design of a retirement income solution for a qualified retirement plan and this has caused some fiduciary risk concerns. However, a default post-retirement strategy does exist for qualified DC plans which specifies the required minimum distribution that must be drawn at age 70.5 – this has the features of being flexible and delaying income (United States Government Accountability Office, 2011) but does not provide longevity protection or a stable income stream.

4.2.4. Our analysis indicates that strategies that directly address the criteria individuals need and value in post-retirement would make more sense for retirees than the single products currently used in most countries. The questions remain about how and when the different component parts should be used to target these needs.

4.3. Comparing the Three Post-Retirement Components Against the Primary Criteria (Needs)

4.3.1.

-

1. Longevity protection – of the three options, the only one that provides longevity protection is an annuity. However, we note that in countries such as South Africa, where the average life expectancy is less than 60 years (World Bank, 2015), it is less financially prudent to lock up an individual’s retirement account into a strategy that provides longevity protection.

-

2. Stable real net returns:

-

a. Investments that provide growth net of fees – cash does not provide growth; annuities and investment accounts can provide growth. The most popular type of annuity purchased in post-retirement delivers fixed nominal payments and does not provide growth. Escalating market-linked annuities can provide inflation protection (further detailed below in point 3) but not necessarily in all cases. Individual accounts can be invested in a wide variety of different asset classes, some more likely to provide growth than others.

-

b. Protect against risk of significant capital losses – a reduction in the size of the account near the start of retirement can seriously impair an individual’s ability to live in the manner in which they had planned for a sustained period. Cash does not experience large losses in nominal terms. Fixed annuities are guaranteed so also do not experience large losses once purchased. Index/market/stock-linked annuities and individual accounts that invest high proportions in growth assets are more likely to suffer from large losses than those that do not.

-

-

3. Inflation protection:

-

a. Increases in the costs of goods and services needed in retirement – cash and fixed annuities do not provide protection against this. Inflation-linked annuities guarantee inflation protection. Individual accounts that invest heavily in growth assets may provide inflation protection over the longer term (Society of Actuaries, Reference Rocha, Vittas and Rudolph2011). It will likely require a combination of different growth assets and dynamic management to target the stable real returns required (Financial Services Institute of Australasia, 2015).

-

b. Shock increases in inflation – cash and fixed annuities also do not provide this type of protection. Index-linked annuities do provide this type of protection but it is often lagged. It is theoretically possible to have an individual account managed in a manner that dynamically moves between the different assets at different points in the inflation cycle but, in reality, most strategies are unprepared for sudden shocks to inflation.

-

-

4. Flexibility – the ability to access assets to manage unexpected increases in consumption (not related to inflation). Cash in hand provides the greatest flexibility in terms of meeting unanticipated spending needs (provided there is enough money in the bank to meet that need). With some account-based pensions systems, there is flexibility to increase the withdrawal amounts or access lump sums, sometimes on a means-tested basis. The traditional annuity market offers little flexibility, by its very definition. Contracts may have surrender values, but these tend to be impaired by punitive charges.

4.3.2. Figure 12 shows that, when comparing products against their primary criteria, cash lump sums are the weakest when judged against these criteria and that individual accounts, depending on the investment strategy underlying these accounts, are the strongest. It is also useful to note that annuities can be regarded as complementary to individual accounts and so it is possible to envision combining these into a solution to get the best of both for individuals.

Figure 12 How do the typical components fare on our primary criteria?

4.4. Comparing the Three Post-Retirement Components Against the Secondary Criteria (Wants)

4.4.1.

-

1. Predictability of income – fixed annuities, index-linked annuities and cash provide the most predictable income. Market-linked annuities and individual accounts are less predictable as their ability to make payments is dependent on the underlying assets.

-

2. Legacy benefits – cash and individual accounts offer good legacy benefits in case the retiree dies soon after starting to draw benefits. Annuities are generally the least attractive from this perspective unless spouse/dependant terms have been included in the contract. Even if this is the case, the benefit to the spouse is likely to be less than for the primary contract holder.

-

3. Simplicity – as previously discussed, it is often difficult to know what is going on inside an annuity. The fees are also less explicit than some other of the options considered above. Individual accounts in general are fairly transparent regarding the investments, especially in more regulated markets.

-

4. Adequacy – this relates to the amount that can be bought. Cash will appear poor on this measure as cash rates are extremely low in many countries in instant-access bank accounts. There are points in time when annuities look poor value for money due to low bond rates and there are times when equities within individual accounts seem expensive relative to history. At other times both of these can look attractive.

4.4.2. Figure 13 shows that when looking at how the components stack up against the secondary criteria, a lump sum payment appears to be the most attractive. From a political angle, the “crowd pleaser” is also the cash lump sum as it ticks more of the secondary/“want” criteria but this provides little to individuals in terms of sustainability and meeting inflation-related costs in old age.

Figure 13 A different story on the secondary criteria

4.5. Comparing Countries’ Post-Retirement Solutions Against the Primary Criteria

4.5.1. Figure 14 looks at the most popular method of DC retirement provision in each country and how they compare against the primary criteria outlined previously. It can be noted that none of the systems is able to tick all of the boxes. Systems that are primarily based on annuities/longevity protection often do not have growth and ones that offer the flexibility of investing in growth assets through individual accounts do not offer longevity protection.

Figure 14 No market satisfies all the criteria

4.5.2. If a country offers retirees a choice of options, this can be beneficial only if structured well and communicated clearly. For example, in Chile, retirees can choose between an annuity and a programmed withdrawal account – by considering their own circumstances and the prevailing market environment, the tools are arguably provided to meet all of the needs. However, this is at the expense of simplicity and only a relatively small proportion of retirees can make active decisions with these criteria in mind.

4.5.3. In all major DC markets, the post-retirement strategies comprise three basic components: lump sum, account-based withdrawals and annuitisation. By assessing first how the components stack up against the established requirements and then how selected markets’ systems fare, we identify a shortfall in the current provision. This is not unexpected – since very few markets are mature enough yet for DC savings to be a significant proportion of a typical individual’s total retirement benefits, limited attention has been paid to the issue so far. However, this is beginning to change, as the legacy from DB-to-DC switches in the 1990s and 2000s begins to impact new retirees; post-retirement strategies are increasingly at the forefront of individual, political and commercial minds.

5. Principles for a Successful Post-Retirement Solution

Our findings indicate that the ideal solution must go beyond being simply an investment portfolio. It must be an overall strategy for meeting retirees’ needs and, just as there is an accepted role for default arrangements in pre-retirement, it is time to install sensible principles for post-retirement.

5.1. The Use of Default Arrangements

5.1.1. In the accumulation stage, default arrangements typically mean a minimum contribution level and a specified investment strategy. When individuals are auto-enrolled into the plan and do not engage to make an investment decision, their contributions are allocated to this default strategy, typically selected by the plan sponsor to give exposure to a balanced investment portfolio creating long-term real returns.

5.1.2. These default strategies tend to be widely used, either because people do not engage or because they accept it as a good “recommendation” from the plan sponsor. Greater active involvement should be expected from individuals at the point of retirement, and consequently perhaps a post-retirement strategy has more of a guidance role or a “nudge” in the right direction rather than as protection for the unengaged. Bearing in mind the key risks previously analysed, it should manage individuals’ exposures to the key risks, as well as overcoming the behavioural problems of under-investing or over-spending.

5.1.3. As in pre-retirement, absolute compulsion to follow a certain route in post-retirement is not needed. Many people will be willing and able to choose their own path, in terms of investment strategy, income to target and use of insurance products. The principles we advocate provide guidance for those other retirees, who are more vulnerable to making inefficient choices.

5.2. What are the Features of a Successful Post-Retirement Solution?

5.2.1. Our research indicates that the most complete post-retirement solution for individuals should have as many “green lights” in the primary criteria box as possible. By focussing first on meeting the “needs” of retirees, rather than the popular, comfort-giving “wants”, this follows the same thinking as pre-retirement defaults: providing the most suitable route for the unengaged or the unsure.

5.2.2. As previously stated, no single product achieves these criteria, so a combination of components is required. Since the impact from the various risks changes as the retiree ages, the solution should focus on maximising risk-controlled growth opportunities in the early stages before adjusting to protect against longevity risk later on. This approach can result in retirees still having a choice at retirement both in relation to the type of investments and the type of longevity protection provided. Solutions could be “approved” as meeting a set of specific “needs” criteria.

5.2.3. Using our earlier starting assumptions of an individual at the point of retirement who has saved 12× final salary and aims for a 60% replacement ratio, escalating in line with inflation, the textbook strategy would be to buy an immediate escalating annuity to meet these income needs exactly, as shown in Figure 15. This would require the annuity to be priced at 5%, that is, the first payment is 5% of the purchase amount (5% of 12× salary equals 60% of salary, as per the targets outlined above). However, the current prices of immediate escalating annuities are much more expensive than this in many countries, due to low interest rates and improving longevity. In addition, with an annuity of this type, there is very little flexibility, making it difficult to deal with changing needs later in life.

Figure 15 If annuities were affordable

5.2.4. Given what we know about the changing risks with age, we can look at three other options:

-

a. Account-based income and deferred annuity (Figure 16).

-

b. Account-based income and buy annuity later (Figure 17).

-

c. Account-based income and immediate annuity (Figure 18).

Figure 16 Account-based income and deferred annuity

Figure 17 Delayed annuity purchase

Figure 18 Combined strategy from outset

5.2.5. Taking a closer look at these three ideas, the first involves splitting the account at the point of retirement into a lump sum for investment and buying a deferred annuity with the remainder. In the first example, as shown in Figure 16, 30% of the account was spent on the annuity, which would begin to pay-out on the retiree’s 80th birthday. Based on our analysis, and considering UK male longevity, we suggest that the age chosen for the deferred annuity to start should be around 80–85, as this is when longevity risk starts to dominate the other risks as shown earlier. The rates for deferred annuities are cheaper than immediate annuities since there is a delay (15 years in our example) before the first payment, during which time returns will compound up and some of the retirees will die. From the insurance company’s point of view, this allows greater investment freedom to pursue higher returns and experience gains from mortality risk pooling if they have priced the risks correctly. In this strategy, the risk is of the account-based element running out at some point. It is used to fund the first 15 years’ pension payments and then to “top-up” the annuity pay-out to the desired income level (60% replacement ratio) thereafter. The aggressiveness of the investment strategy and the prevailing market environment will dictate the timing of this eventual depletion of funds. In our back test analysis, using a balanced portfolio of 50% bonds and 50% equities, and actual historic market data, the median expiry age of the account is around 89 years.

5.2.6. The second strategy delays the purchase of the annuity, as shown in Figure 17. The entire account at retirement is invested and the required 60% replacement rate income is withdrawn over the first 15 years, then the balance remaining is used to purchase an immediate annuity. Since the retiree is then 80 years old, as opposed to 65, the available annuity rates would be more favourable. From the insurer’s point of view, there will be fewer pay-outs due to the lower expected future life expectancy. (Using standard UK mortality tables (Office for National Statistics, 2012), a 65-year-old can expect to live for around a further 17 years, whereas an 80-year-old typically has just over 7 years left.)

5.2.7. There are risks involved in this regarding the future annuity rates available 15 years after retirement. Economic and demographic conditions may have changed significantly by then, impacting annuity prices. Also, if the investment returns achieved in the first 15 years are lower than anticipated, the balance available at age 80 may be insufficient to buy an adequate annuity. Our real-life back test shows that at age 80, the median remaining account value could afford an annuity of around 82% of the target level of continuing the 60% replacement rate.

5.2.8. The third strategy is to combine account-based and annuity components together from the very start of retirement, essentially buying an annuity to cover a very basic income level and using the account to top this up to the required level, as illustrated in Figure 18. The annuity, in this case, could be level or escalating in line with inflation. This is similar to how State benefits dovetail with personal/corporate benefits in many markets. In Figure 18 it is shown as a level annuity, and therefore the top-up withdrawals taken from the remaining account will increase over time. The initial decision regarding what proportion of the savings to annuitise will likely be taken based on the available rates and what the retiree wants/needs as the basic income level (and how much is provided separately by the State, if any).

5.2.9. Depending on the investment strategy for the account and the market environment, there may come a point in time when the account runs out and the available income reverts back to the basic annuity level only. In reality, in around half of back test scenarios the account survives past age 90, although in 30% of cases, it has expired by age 85.

5.2.10. When evaluating our preferred strategy (account-based income and deferred annuity) against the primary and secondary criteria, Figures 19 and 20 show that this strategy meets more of the needs and wants that individuals have in post-retirement.

Figure 19 Blended solutions meet more of the needs of individuals in post-retirement

Figure 20 Blended solutions also meet more of their wants

5.2.11. These are simple examples, given as illustrations only. In practice, required withdrawals, investment strategy and annuitisation ages will vary based on individual circumstances and experience. Annuity rates will vary over time and successful commercial solutions are more likely to spread their purchase over time rather than using single premiums. Cultural and regulatory considerations will also influence the favoured strategies by jurisdiction.

5.2.12. Although those designing the default strategy should first be concerned with the primary criteria, strategy differentiation is more likely to come in the detail and added extras. For example, using annuities with survivor benefits, implementing guarantees at the account-based stage or providing annuity cash-out payments could all increase the solution’s appeal on the secondary criteria. Costs would be involved, and the extent to which the benefits outweigh these is a matter of individual preference.

5.3. Opting Out

5.3.1. The strategy would be designed to appeal to as high a proportion of people as possible, but cannot be ideal for everyone. This is why it should be optional, rather than a mandatory set of rules. This allows people to opt out in favour of a different approach of their own choice.

5.3.2. People should only be allowed to opt out if it is suitable for them to do so. This effectively “nudges” people in the right direction. Opting out requires a judgement about the circumstances in which someone should be allowed to opt out. In some markets, such as the United States, Singapore and Australia, one-to-one financial advice or guidance at retirement is encouraged – a similar framework could be adopted to ensure retirees have considered their options fully before opting out. Although perhaps an artificial construct, this creates a hurdle which will deter some people from opting out.

5.3.3. The State may ultimately bear the burden from those who opt out and subsequently deplete their savings too early, which makes this another politically sensitive matter. Given the varying needs and preferences of individuals, however, we believe that opting out should not be quantitatively means-tested. Open, realistic communication, combined with sensible alternative options is preferential to mandatory annuitisation.

5.4. The Global Solution to the Post-Retirement Problem

5.4.1. The move from DB to DC has transferred longevity and investment risks from the plan sponsor to the individual plan member. Without the actuarial cross-subsidies implied by pooling these risks, the danger of outliving one’s savings is significant. We need to find a better solution to this problem than an early grave.

5.4.2. The key risks to which an individual is exposed are inadequate savings, unexpected outcomes in investment, inflation and longevity as well as forced changes to consumption needs (e.g. healthcare). To manage these risks in a balanced and robust manner requires a hybrid strategy of individual investment accounts and insurance.

5.4.3. Faced with uncertainty and the availability of many choices, in the absence of good quality advice or guidance, retirees are likely to make sub-optimal decisions. Some have therefore argued for the creation of a post-retirement “default strategy”, as this can offer a better starting point for these decisions.

5.4.4. Having a single default fund in post-retirement is not the approach we advocate for a number of reasons:

-

1. Everyone’s circumstances will differ and so they should have the ability to select the appropriate individual investment fund and longevity protection that fits their needs.

-

2. Due to these differing circumstances, there is a risk that any one fund selected as a default will not be suitable for an individual and this may result in a mis-buying/mis-selling risk.

-

3. Financial literacy, while low in many markets, does appear to be improving in some (or at least a lot of money is invested in this area by governments and NGOs). Additionally people have more access to information than ever before and may be more willing and able to research and make investment decisions in future.

-

4. While choice is not always used well, it is certainly popular in a number of markets. To suggest that a default should be only one fund would reduce the attractiveness.

-

5. In practice it is difficult to see how one would get agreement on what should constitute a “default”.

5.4.5. Rather like building regulations that ensure physical constructions are built on a set of robust principles, we favour an approach that seeks to establish a set of principles which are the necessary conditions for good quality retirement solutions. In the United Kingdom there have been preliminary discussions about “Kitemarking” funds as suitable for retirees to manage the issue of newly available choice at retirement (the Kitemark is awarded to a product or service that has been tested independently to show that it meets suitable standards). This is synonymous with funds that are “QDIA-approved” (meaning default-approved) in the United States for pre-retirement. However, an over-arching solution is far broader than simply a fund or insurance product.

5.4.6. In conclusion, the ingredients for a successful solution will comprise the following components:

-

○ Stable, real investment returns, net of costs.

-

○ Reliable protection against longevity risk, later in life.

-

○ Flexibility to adapt to changing requirements.

-

○ Simplicity in implementation and communication of outcomes.

5.4.7. A successful solution will inevitably be a blend of investment and insurance components in a balanced manner. With lengthening life expectancies, we anticipate strategies will blend a growth and income account-based approach for the first 15–20 years after retirement with longevity protection engaging in later life.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Schroder Investment Management Ltd for the funding of this paper and to the following individuals for comments, edits and reviews: S. Bowles, T. Darnowski, D. Hindocha, K. Howard, S. Kalra, P. Marsden, D. Morris, A. Nanwani, A. Nilsson, G. Ralston, A. Toledo, C. Yong.

Disclaimer

The authors wish to express thanks to Schroder Investment Management and its employees for support in the production of this paper.

Appendix 1: Assumptions

Modelling assumptions:

For Figures 14–19 and 25 to 27, the following assumptions have been used:

Retiree assumptions

-

∙ Final salary=$50,000

-

∙ Replacement ratio=60%

-

∙ Savings as a multiple of final salary=12 times

-

∙ Retirement age=65 years old

-

∙ Annual withdrawal assumed as being taken at half way point in year.

-

∙ Mortality probabilities calculated from “UK Life Office Pensioners, males, Combined, lives” data.

Investment assumptions:

-

∙ Periods analysed=1952–2013

-

∙ Cash fund: 100% invested in US 3 million deposit rate. Proxies used US 3 million T-Bills and JPM US Cash 3 m

-

∙ Equity fund: 70% US equity, 30% global equity. Proxies used S&P500 and MSCI EAFE

-

∙ Balanced fund: 50% US equity, 50% US bonds. Proxies used S&P500, US Treasury 10y yield, Barclays US Aggregate

-

∙ Inflation: US CPI All Urban seasonally adjusted.