On 29 November 1963, the Daily Mail carried a headline: ‘Church Defied. RC Woman Doctor Sets Up Family Planning Clinic’.Footnote 1 The article continued:

tall, auburn-haired, and the mother of seven young children, the 36-year old doctor said: …“I am taking a stand on something we Catholics cannot sidestep any longer”.Footnote 2

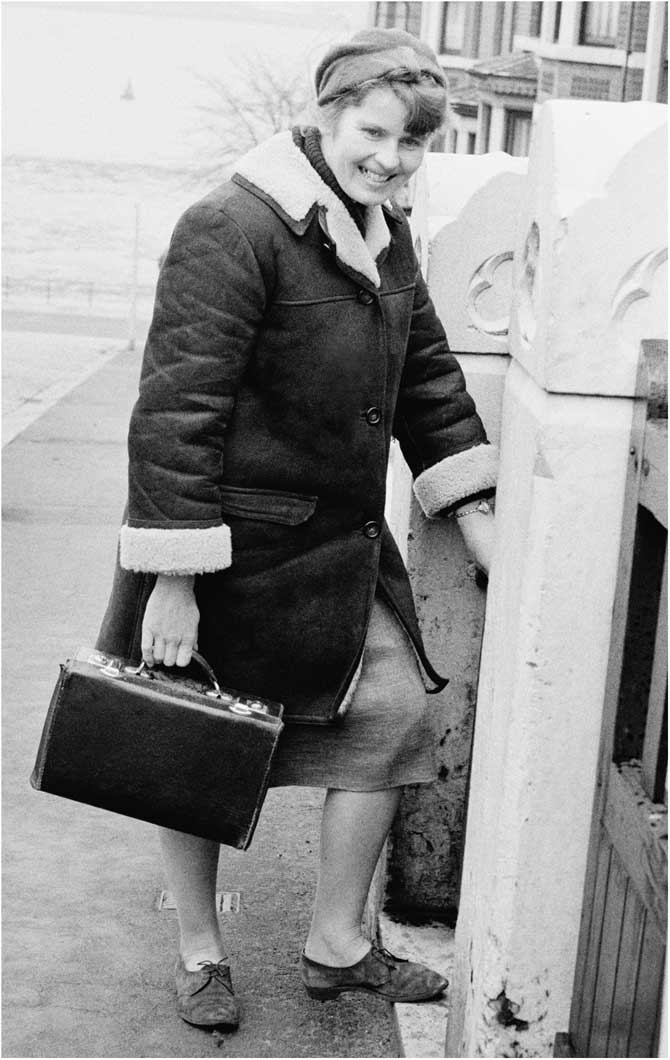

Dr Anne Bieżanek’s decision to open one of the first Catholic birth control clinics in the world in the front room of her home surgery in Wallasey, Merseyside, would continue to be headline news here,Footnote 3 and in the United States,Footnote 4 for the next twelve months (figure 1).

Figure 1 Dr Anne Bieżanek at the front gate of her home surgery, medical bag in hand. Note that this photo, and figure 2 were taken by the well-known ‘paparazzi’, Ray Bellisario. Permission granted by Getty Images.

Alongside this pioneering initiative, which she deemed a ‘Christian aid programme’,Footnote 5 Dr Bieżanek published a strident, 150-page justification of her actions and their implications. With international distribution through Pan books,Footnote 6 and Harper and Row in the US—while banned in IrelandFootnote 7 —it was entitled All Things New: The Declaration of Faith, referencing the eschatological, indeed apocalyptic promises of the Book of Revelation. In the appendix to the book, Dr Bieżanek printed anonymous extracts from some of the thousands of letters she had received from all over the world and one such read:

I hope I will live to see the day when a Higher Domestic Science paper will have a question on the role played by Dr Anne Bieżanek in liberalising the RC Church to birth control [and] its effects on raising the status of women and on family life in the latter half of the 20th century.Footnote 8

This non-Catholic female correspondent would be disappointed, perhaps, that this article constitutes the first extended treatment of Dr Bieżanek’s writings and work, and the part they played in anticipating broader debates about sexuality and contraceptive cultures in late twentieth century Britain. Yet in the English Catholic Church of the early 1960s, Dr Bieżanek’s transgressive writings and provocative actions made her notorious, and clerical commentators disparaged or hailed the force of her intervention within increasingly controversial debates about birth control and the ‘primary ends’ of marriage. For example Father Alban Byron SJ, writing in the Catholic Missionary Society’s journal, the Catholic Gazette, violently disagreed with almost all of Dr Bieżanek’s contentions but was forced to acknowledge, euphemistically, that All Things New ‘is the most extraordinary marriage book I have ever read.’Footnote 9 Much more positively, Canon Harold Drinkwater, a respected catechist and popular author in his own right,Footnote 10 praised the book for eschewing:

all those tactful euphemisms and soft-peddling, those delicate nuances and innuendos, those discreet circumlocutions, which so often oil the chariot wheels of truth and which those of us who write under constant censorship get so good at.Footnote 11

Writing a few months later in Search, he went further in claiming:

Let nobody imagine for a moment that the author is some kind of nagging eccentric or notoriety-seeker … Here is a book in the same category as Newman’s Apologia. … an agonia, on the mind of the Church of today, as it re-enacted itself in one lonely human soul.Footnote 12

As this article will explore, nor was there consensus amongst contemporary Catholic laity or clergy about Dr Bieżanek’s forthright articulation of the issues. Prompted to write to the Bishop of Shrewsbury by Dr Bieżanek’s public actions and the publication of All Things New, Father Joseph Howe of St Ann’s Cheadle deplored the ‘“open forum” of today, in which no longer were the secret and sacred things reserved for God alone’.Footnote 13 In fact, he attributed the catastrophic degeneration of moral standards to such public commentary, which he castigated as the writings of ‘querulous women [which] offend against taste’.Footnote 14

The increasingly frequent, indeed insistent written interventions made by Catholic women, and some men,Footnote 15 writing about ‘married love’ and birth control in the period after the Second World War is only now beginning to receive academic treatment in a British context.Footnote 16 More scholarly research has been undertaken within an American Catholic historiography considering, for example, the pioneering feminist efforts of Margaret Sanger through to Dr John Rock’s explosive bestseller The Time Has Come (1963).Footnote 17 Leslie Woodcock Tentler’s consummate explorations of shifting attitudes to and the adoption of contraception by American Catholic men and women have paved the way for comparable studies in other Anglo-European contexts.Footnote 18 This article takes up this emerging agenda within an English Catholic landscape, and seeks to excavate the theological and practical contributions of one British woman to a wholesale rethinking of the relationship between conscience and clerical authority in the years surrounding the Second Vatican Council.Footnote 19 As it illustrates, the birth control debates and the emergence of new contraceptive technologies were lightening rods for these broader social and theological issues.Footnote 20 As a case study, perhaps, of a ‘Catholic Marie Stopes’, it forms part of a larger, on-going project examining shifting discourses about love, marriage, sexual knowledge and contraceptive practices, and seeks to integrate the experiences of British Catholic laity and clergy so as to interrogate broader assumptions about chronology, agency and secularity charted by historians of gender and sexuality.Footnote 21 Building upon the insights of Callum Brown on the centrality of gender and biography in interpreting the religious changes of the sixties,Footnote 22 though coming to quite different conclusions about the timing and effects of these radical re-drawings of morality and theology, it seeks to evaluate the ways in which Dr Bieżanek—who presented herself as an ordinary, working-class Catholic ‘everywoman’—negotiated this shifting social, moral and religious terrain. It also draws upon recent revisionist work exploring the formative role played by religious discourses alongside, or in contrast to the secular social sciences in the publications of intellectuals and experts attempting to reformulate love, marriage and sex within a ‘modern’ age.Footnote 23 Using the writings and public activities of one ‘querulous’ woman to prize open broader debates about birth control well before the Humanae Vitae debacle in 1968, it makes an innovative intervention through demonstrating the contribution Catholicism made in the movement from puritanical reticence to public candour in post-war British sexual cultures.Footnote 24 It is argued that Dr Bieżanek’s private correspondence and public persona illustrate the ways in which the boundaries between the public and private, and spiritual and sexual politics were being increasingly re-negotiated by many Catholics through the 1950s and early 1960s. Understandings of the dictates of conscience, intimately intertwined with class, gender and the weakening societal premium placed upon deference and obedience to authority (represented by her husband, priest, Bishop and ultimately the Pope), are key motifs of Dr Bieżanek’s exceptional and sensational life story.

Behold the woman: Anne Bieżanek’s biography and her theology

When I interviewed Anne Bieżanek in her home in Wallasey, just a month before her death on 30 November 2010, she opened our conversation with a startling reference to Charles de Gaulle. In response to my querying her conversion to Catholicism in her late teens and the way she ‘crossed swords’ (as she put it) with the English Catholic Hierarchy, she responded:

I read something that was written about General de Gaulle—[that] he had a precocious sense of destiny. I said “oh yeah, that’s me, I have a precocious sense of destiny”. And, I sort of bored ahead, I was going to, I [don’t] know, I was going to be canonised or bust. Really serious stuff.Footnote 25

A cerebral intensity indeed characterized most of Dr Bieżanek’s life. Raised in a Quaker/Anglican household and educated at the progressive Dartington Hall School (and then Dollar Academy when her family moved to Scotland), her father, Ben Greene, was a British Labour Party politician and pacifist interned during World War II on account of his fascist associations.Footnote 26 Describing visits to her father in Brixton where he was imprisoned before his landmark civil liberties trial in 1941, Dr Bieżanek foregrounded his conscientious objection and self-consciously drew inspiration from this parental legacyFootnote 27 rather than the more illustrious careers of his cousins—author Graham Greene and former Director-General of the BBC, Hugh Carleton Greene. Critiquing Jeremy Lewis’ 2010 collective biography of the family,Footnote 28 which she characterized as ‘a huge book, all about these wretched Greenes’, she loyally objected:

I don’t think [he] does [my father] justice. I think he gives far too much space to Graham, who I’ve never had any use for. He’s not, I mean, what’s so great about Graham? I mean his novels were, I don’t know why people are so awed by him! Can’t see anything in his novels at all.Footnote 29

When I expressed surprise that she did not esteem what are often thought of as ‘quintessentially Catholic’ novels, pivoting on themes of sin, guilt and a tortured conscience,Footnote 30 it is to Graham’s fictionalization of his relationship with his wife that she turned. As Dr Bieżanek characterized the novelist: he was ‘an absolute fraud’ in portraying himself as ‘some poor Catholic whose wife won’t divorce him’ when she is convinced, through extended conversation with Vivian Greene, that it was rather the husband who strenuously resisted the end of the affair.Footnote 31 This prioritization of truth telling, of authenticity at whatever cost, an aversion to hypocrisy and a slight sense of persecution emerge as key leitmotifs and intellectual priorities in Dr Bieżanek’s own biography.

The bare facts of Anne Bieżanek’s life—though completely unknown today—were daily fare for a 1960s newspaper reading and television viewing public. From the completion of a medical degree at the University of Aberdeen and the commencement of her medical practice in psychiatry in 1951, alongside her early marriage age to Jan Bieżanek (a Polish émigré and former judges advocate, then merchant seaman), most explanations of her public activities in the early 1960s dwelt on the string of ten pregnancies and seven children in thirteen years which led her to question the Catholic Church’s reproductive teaching. She herself was complicit in this public-fashioning, presenting herself in the media as a respectable (but beleaguered) mother and professional woman, the victim of draconian and irrational dogma, which led inexorably to a questioning of the Church’s position and an inevitable confrontation with the Church authorities. These character outlines are fully sketched in her own book and inform all subsequent renderings—such as the brief discussion of her clinic in Bernard Asbell’s ‘biography’ of the pill and Lara Mark’s history of contraception.Footnote 32 Asbell’s representation of Dr Bieżanek as a ‘wild woman’, including his descriptions of her as ‘tall, handsome, and blond … intense [and with] a tongue like a whip’Footnote 33 was replicated—under the chapter heading ‘Rebel with a Cause’—in Christine Dawe’s recent biographical sketches of prominent Merseyside personalities.Footnote 34 In these portraits, constructions of femininity, maternity and celebrity are mobilised to situate Dr Bieżanek’s protest within the gendered landscape of sexual politics, and a 1960s assault on religious orthodoxy. Such framings are particularly prominent in the television reporting (and photographic representations) of her rebellious reception of Holy Communion at Westminster Cathedral in May 1964, which will be examined in more detail.

Dr Bieżanek’s biography ultimately escapes, however, such neat categorization. On the one hand, rhetorical modes common in women’s autobiographical writings are present,Footnote 35 such as her disclaimer of scholarly expertise and originality,Footnote 36 an appeal to emotional authenticity, and a relational (and classed) impulse to write in solidarity for other women ‘very few of whom were likely to be as well equipped as I in physical and educational resources.’Footnote 37 Her author’s note, on the opening pages, evoked the writing process at the family’s holiday cottage in Cornwall, with her seven children entertained by their grandmother to facilitate the necessary quietude and leisure. Directly addressing the reader, she disclaims:

do not look for polished writing or the well-turned phrase. This book simply pours forth under its own momentum, with every word coming straight from the heart.Footnote 38

And later on:

If I can help anyone with these reflections of mine then I am only too glad to do so, and it will help me to come to terms with the unspeakable bitterness and suffering I have myself endured on this matter….Footnote 39

Recalling Canon Drinkwater’s analogy with Newman, All Things New is a revealing spiritual autobiography and psychological portrait of its author. The opening chapter narrates the fervour and emotional intensity of her conversion, her naïve, romanticised attraction to war-torn Poland (and by extension to its national faith and refugees), and the desire to commit unequivocally and zealously to her new faith. Only against this backdrop is it possible to understand fully the agonized wrestling with conscience and Church teaching that underpinned her decision to take the pill on prescription in 1962 and then open a clinic for Catholic wives the following year. The book is also remarkable in its fearless and, at that time, profoundly counter-cultural discussion of mental illness—encompassing Dr Bieżanek’s work in psychiatric institutions throughout England in the 1950s and her encounter with patients tortured by religious ‘scruples’,Footnote 40 through to her own confession (omitted in other biographies) of her breakdown and self-committal to an Edinburgh mental hospital when pregnant with her sixth child.Footnote 41 In an ironic sense, and one that she herself might not have acknowledged, Dr Bieżanek’s autobiography might be incorporated into the tradition of mid-twentieth century Catholic novels in its interrogation of a culture of sin, guilt and the contortions of conscience.Footnote 42 Another Shade of Greene to add to the family album.

Yet the theological sophistication of Bieżanek’s book and its frank and revealing self-analysis marks it out from Graham Greene’s oeuvre. To this end, the second half of the book is a spiritual treatise which undertakes a scholarly but accessible reconceptualization of Catholic teachings on birth control through the lens of the Bible, the writings of St John of the Cross and popular Mariology. Taking her title from the final book of the New Testament,Footnote 43 apocalyptic strains and the conceptualization of the current crisis as ‘birth pangs’ of a new order infuse the writing. Within Dr Bieżanek’s rending of the ‘revolution’ unfolding,Footnote 44 there is a presentist, post-war democratic impulse to the analysis. The ideological fascism of the Nazis (and their treatment of Poland) is always in view,Footnote 45 and resistance to the ‘spiritual totalitarianism’ of the institutional Church,Footnote 46 alongside a rightly understood theology of women’s nature and married love free of past distortions, is presented as a just war or judgment day.Footnote 47 In an inclusive, cross-class rallying call, Dr Bieżanek acclaimed:

This is not a battle of kings and princes; this is the battle of the common folk and the little people. This is THEIR battle; the issue of their right to be themselves; the sources of the conflict are their own secret nightmares; the outcome is to be one that expresses the might of the living God within them.Footnote 48

It is, therefore, conceived as another ‘people’s war’ or further proof of the flourishing of a vibrant democratic culture in Britain, using salient language of the day.Footnote 49 Articulating a broader priority in post-war Catholic popular piety on an incarnational, this worldly, Christology of CAFOD rather than the cross,Footnote 50 Dr Bieżanek pithily framed these preoccupations, in language directly reminiscent of John Robinson’s contemporaneous best seller ‘Honest to God’,Footnote 51 through the birth control issue:

Few are any longer interested in heaven ‘up there’. All are hungering for the ‘living bread that came down from heaven.’ We want our heaven on earth, and why should we not?Footnote 52

Drawing upon newly-circulating pamphlets such as the Dominican Victor White’s God and the Unconscious (1952), Dr Bieżanek interwove Old Testament references to Israel’s suffering and exile, with reflections on the prophetic voice today in the ‘anathematized … coming under the care of psychiatrists’ or recognition of a ‘hypothetical Christ, hidden in my very real, “Baptist-like” patients.’Footnote 53 The voice crying in the wilderness, but with some expectation of the inauguration of a wider movement, is her characterization of her own near-messianic cri de coeur. In Dr Bieżanek’s explanatory schema, the mysticism of St John of the Cross—which she acknowledged fifty years later remained a source of spiritual sustenance—explained the present-day crisis in the Catholic Church.Footnote 54 As the counter-reformation Carmelite mystic affirmed, ‘to attain the supernatural knowledge, which is the daylight of heaven, the soul must [first] traverse this night.’Footnote 55 The acrimony and confusion surrounding the Church’s position on sex and contraception, particularised in its treatment of herself as a spokesperson for countless suffering Catholics should, she asserted, ‘be welcomed as a sign of great portent.’Footnote 56

The analytical framework that sustained Dr Bieżanek’s wholesale critique of traditional natural law ethics and its restatements (such as Pope Pius XI’s 1930 encyclical Casti Connubii) was her appeal to a very ‘high’ Mariology—indeed the controversial proposition intensely debated (and by November 1964 narrowly rejected at the Second Vatican Council) of Mary as Co-Redemptrix.Footnote 57 Seeing off what she saw as squeamish ecumenical qualms about Mary as a ‘barrier to reunion’ then fashionable in liberal Catholic circles by disparaging them as the concerns of ‘an “all boys together” kind of tea party’,Footnote 58 Dr Bieżanek urged Catholics to recognise the fragmentation of Christian truth at the Reformation and to embrace their safekeeping of a unique part of revelation history which ‘is giving to the woman, the mother of Christ, a status in the scheme of salvation equal to that of her son.’Footnote 59 As she asserted:

Christ’s work of redemption cannot be separated from the work of His mother, who under the providence of God literally made Christ’s advent possible, and translated it from a prophecy to a reality, by her willingness to fulfil the destiny that had been laid upon her.Footnote 60

Eschewing what she thought a facile (and conceptually problematic) identification of Mary as a mother like all Catholic mothers, Dr Bieżanek’s reasoning remained grounded in the theological implications to be drawn from the Nazareth story. The Church’s teaching on Mary’s perpetual virginity, alongside the incarnation narrative, led her to recognise:

in the matter of the conduct of her marital relationship it is clear that she has no specific message to give her spiritual children, for her marriage was unique. … But from her willingness to launch forth in a spiritual adventure of the first magnitude there are many conclusions to be drawn.Footnote 61

One telling conclusion, for the purposes of her current argument, was the implications flowing from Mary’s recognition as a ‘Second Eve’. Meshing popular Mariology to modern technology, she claimed:

the advent of oral contraception appears to me to be an event of as great a significance for mankind as was the expulsion from the Garden of Eden … The contraceptive pill has come to woman, as a heavenly reprieve from that primordial doom. It is my contention that this must be willed by God, and I say that the appearance of these drugs can be taken as a sign of God’s final pardon … [a] reprieve for the daughters of Eve … won for them by ‘the Second Eve’…Footnote 62

As this section of her treatise concluded, ‘it is through a knowledge of the Virgin Mary that Roman Catholic men will learn to honour all women, and bring the days of their neglect to an end’.Footnote 63 In the years that followed, particularly in the discussions surrounding the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control and hoped liberalization of the Church’s teaching (which were to be unequivocally dashed by Pope Paul VI’s encyclical), compassion, pragmatism and appeals to ‘secular’, rational and scientific reasoning were foregrounded.Footnote 64 Dr Bieżanek’s inventive, if ultimately unsuccessful contribution to this debate, was to try to offer a rhetoric of continuity, a mechanism to reconcile the accumulated (prohibitive) Church teaching with the undergirding authority of tradition and the sensus fidelium as a ‘source’ for Christian development. In her attempt to circumvent the polarization of the debate into factions (traditionalist and progressives) and the juxtaposition of obedience and conscience, All Things New offered an avenue through the impasse—a way ‘the whole hierarchical paraphernalia is going to survive the massive kick in the teeth it would receive if and when an official “about turn” is forced on it’.Footnote 65 Traditional hierarchies and unquestioning deference to authority did not, of course, survive the Catholic Church’s spiritual ’68—in common with the experience of other Western European institutions in this decade.Footnote 66 Nor did Dr Bieżanek’s embattled commitment to the Catholic Church endure into the 1970s, for in being rendered a non-communicant she felt she was ‘sort of ex-communicated by the back door you might say’.Footnote 67 Negotiating the personal implications of her stance with her husband, her local parish, her Diocesan Bishop and ultimately with the President of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, she eventually found a new spiritual home in Pentecostalism, homeopathy and biblical study facilitated by the Open Bible Ministries.Footnote 68 It is these relationships, and her correspondence in the early 1960s with these men in authority, which will now be examined.

‘Shouting from the rooftops’ about things done in sacred places: the letter and the spirit of the law

In her first epistle within an extensive correspondence that lasted over three years, Dr Bieżanek’s opening letter to the Bishop of ShrewsburyFootnote 69 on 13 February 1963 ran in the formulaic terms usually found within the confessional:

In the last 12 months I have run into difficulties in my married life that have compelled me to take extraordinary steps. Steps at variance with my conscience and the teaching of the Church. My reason for acting thus has been the protection of my own health and sanity and thereby the protection of the life of the family.Footnote 70

Implicit within this personal introduction and the outline of her spiritual and marital situation is Dr Bieżanek’s decision to commence taking the pill—which she dated very precisely to 25 May 1962Footnote 71 —and the consequences of this decision in her parish many months later when she was publicly refused Holy Communion at the altar rail. The escalation of this marital decision from a subject of conversation with her priest, to a matter made public at the altar rail and elevated to the Bishop’s correspondence tray, is illuminating of the ways in which Dr Bieżanek melded traditionalist conceptions about marriage (and unrestrained, brutish male sexuality)Footnote 72 with progressive and psychological-informed constructions of women’s sexual desire,Footnote 73 female agency and a marked anti-authoritarianism. For Dr Bieżanek, who fifty years later said that she didn’t feel any connection to feminismFootnote 74 yet referenced in print the ‘liberated feminist with her vote, her education, her legal rights and her dutch cap’,Footnote 75 the personal was indeed political or perhaps, more precisely, theological. The politicised arena in which Dr Bieżanek concentrated her reforming challenge, the social body that she sought to reconfigure with reference to her own embodied, experientially-framed insights, was what she identified as the Catholic Church’s misogynistic understandings of gender equality and sexual relations.

Reconstructing the chronology of events from a voluminous correspondence, the difficulties for all parties seem to have arisen in early 1962, when Dr Bieżanek confided her extreme difficulties negotiating her husband’s insistent and sometimes violent demands for unfettered sexual intimacy to her assistant parish priest, Father Gaskell.Footnote 76 Fearful of yet another pregnancy, but equally scared of the intense disruption to marital stability caused by sexual abstinence, she asked for an alternative line of conduct. Father Gaskell is reported, in All Things New, to have refused to help Dr Bieżanek separate from her husband and, moreover, to have advised that in taking the contraceptive pill she would be refused Confession and Communion.Footnote 77 Distressed by this impasse, his response to her question ‘What then am I to do?’ was ‘I do not know’.Footnote 78 Elsewhere in her letters to the Bishop, Dr Bieżanek acknowledged the pastoral care and support that Father Gaskell had offered—he ‘has always been very kind and generous in the help he has given me’Footnote 79 —alongside her appreciation for his own ‘extreme nervous discomfiture’ requiring ‘for his sake, as much as my own, that the matter … be taken further.’Footnote 80 This young priest’s difficulties in explaining and enforcing the Church’s teaching on contraceptive practice would be echoed in a number of high-profile cases of clerical dissent in the years that followed,Footnote 81 anticipating the so-called ‘northern rising’ of clergy in the Archdiocese of Liverpool who failed to toe the line on Humanae Vitae in 1968. In the heartland of traditional and resurgent Catholicism (and, intriguingly, the early twentieth-century birth control movement), working-class Catholics and their clergy were at the forefront of a revolt deemed one of the most intense in Western Europe.Footnote 82

In the months following May 1962, when Dr Bieżanek had started practising contraception, she reportedly refrained from receiving Holy Communion when attending Mass each week at her parish Church, St Alban’s. As she recounted in All Things New, this stance raised delicate questions from her children, and particularly her eldest daughter who had just started to receive Holy Communion.Footnote 83 Resolving to regularise her situation, she therefore wrote to the priest-in-charge, Canon George Higgins, announcing her ‘intention of receiving Holy Communion along with my daughter on December 8th [1962], the first anniversary of her First Holy Communion’. She concluded this letter by stating that despite Father Gaskell’s ruling that her ‘peculiarities … [prove] an absolute impediment to my reception of the Blessed Sacrament … I do not share his opinion and mean to carry on in spite of it’.Footnote 84 The letter closed by saying that Father Gaskell’s ‘misplaced sense of delicacy’ may have prohibited discussion of the circumstances of her case, but she now felt that she had to face the difficulties directly.Footnote 85 As she later reported on this course of events to her Bishop, she left the ‘way open for him to take any steps he thought right, to prevent or dissuade me.’Footnote 86 Dr Bieżanek’s letter did not receive an acknowledgment, and the following Sunday, she went to the communion rail, as she then did every Sunday following.

This appearance of equanimity and conformity—perhaps echoing the practice of more English Catholics than previously appreciated if the letters in the concluding pages of All Things New are any guideFootnote 87 —was ruptured by an announced parochial visit by Bishop Eric Graser in February 1963. At this time Dr Bieżanek communicated to Canon Higgins her desire to seek a private meeting with the Bishop—ostensibly to talk about his 1961 pastoral letter on the need for a moral crusade and, in a Mary Whitehouse vein,Footnote 88 the sexualizing effects of ‘degrading film and literature’ on ‘Catholic husbands’.Footnote 89 Fearing the consequences of such a meeting—and perhaps censure of his ‘turning a blind eye’ at the communion rail each week—Canon Higgins pre-emptively wrote to his Bishop on 13 February 1963. His summation of Dr Bieżanek and the parochial situation was as follows:

[She] is married to a Pole, a sailor, who is away on long trips. She herself is a doctor, a psychiatrist, and has spent one long period in a mental home as a patient. I have typed out and enclose part of a letter she wrote to Fr Gaskell. From its contents you will be able to judge her to some extent. There are other things which you ought to know but I find it difficult to put it down on paper, but I do hope that you will be very wary in whatever you decide to do. None of us here want to have anything to do with her.Footnote 90

The letter annexed was indeed a curious (and intimate) piece of correspondence written by Dr Bieżanek a month earlier which, in a mystical and metaphorical vein, claimed that Father Gaskell was the spiritual ‘father of [her] bastard child’—by which it is clear she meant her resolve to ‘stir something up’ and which ultimately was ‘delivered’ as her birth control clinic.Footnote 91 Canon Higgins’ reluctance to ‘put down on paper’ the intricacies of her marital difficulties is also in marked contrast to Dr Bieżanek’s own candour in correspondence and, as Adrian Bingham has explored, the increasing willingness generally of the British public to speak and read about sexuality in print.Footnote 92

Read without any background context, nor a sense of Dr Bieżanek’s rhetorical flourish, Canon Higgins’ intervention was clearly an attempt to discredit his parishioner’s approach and indeed cast aspersions on her sanity. Dr Bieżanek’s persistence in seeking an appointment with the Bishop drew a sharp letter from Canon Higgins, which he copied to the Bishop on 21 February 1963 with the covering note:

Please do not be perturbed by the apparent severity of this letter. … This woman has been told that she should not go to communion—she will not accept the teaching of the Church on a serious moral matter. She receives communion and we can do nothing, but that does not mean that I cannot show my abhorrence of her conduct in some way or another.Footnote 93

Expressed in specific form, here is another instance of clerical discomfort with the ‘writings’ and witness of ‘querulous women’, alongside assertions of powerlessness to enforce conformity with the Church’s official stance. Meanwhile Dr Bieżanek’s first letter to Eric Graser, which closed with assurances of her ‘most earnest determination to act correctly,’Footnote 94 had brought the matter squarely to the attention of the Bishop of Shrewsbury.

Bishop Graser proceeded to have a meeting with Dr Bieżanek during the course of his February parochial visitation, but rather than containing the situation, their conversation seems to have hardened the lines of opposition. Writing shortly thereafter on 25 February 1963, Dr Bieżanek thanked the Bishop for his time, courtesy and patience, but her placatory expressions of two weeks earlier had evaporated and been replaced by her own articulation of what ‘acting correctly’ and authentically might entail:

… I do not accept your self-appointed right to act as judge, jury and executioner in this matter, a matter that involves not only the stability of my home but the destiny of my immortal soul and those whom providence has appointed me to influence.

I do not think that you can afford to ignore me … warn your fellow bishops, as soon as possible, that the Church must needs look to her defences in this matter. The Catholic mother is the heart of the Church. That heart is exposed and has already been pierced. It now requires particular attention or it will stop and die.

If the bishops will not look to this, then I will do so myself on my own authority.

You suggest that there is something “unsporting” in my putting the parish clergy in the spot I have put them in. But this is no game. Everything is at stake.Footnote 95

Drawing upon longstanding Catholic rhetoric about the centrality of mothers to the inculcation of the faith and implicitly to devotion to Mary of the Sacred Heart, Dr Bieżanek’s diagnosis of the damage done to the Church through its stance on contraception resonates with the assessment of historians of the sixties who have interrogated the importance of women’s alienation to the wholesale religious crisis of the period.Footnote 96 Yet what is equally surprising is the insight this correspondence provides into the shifting and less hierarchical relationship evolving between priest and people in the lead up to the Second Vatican Council. Despite the anger and self-confident defiance of this letter, a regular—almost weekly—and intimate, indeed familiar correspondence continued between Bishop Graser and Dr Bieżanek. Its terms give a practical but highly unusual demonstration of the enactment of concepts such as the ‘primacy of conscience’, the ‘apostolate of the laity’ and the renegotiation of clerical authority during this decade. Within this remarkable exchange of letters we see the opposing struggles of two ‘devout’ Catholics attempting to negotiate diametrically contrasting positions within the landscape of increasingly unstable Church teachings.Footnote 97

Symptomatic of such struggles was a letter Dr Bieżanek wrote to her Bishop on 19 March 1963, in which she formally announced her intention to ‘gain a footing in Family Planning Circles’ while ‘reconcil[ing] my position as a practising Catholic with work of that kind’.Footnote 98 In a telling precursor to her theological Mariology in All Things New, she enclosed an essay intended as an ‘answer’ to the perceived contradiction between her Catholicism and the provision of contraception. Dedicated to St Joseph, the lengthy essay rehearsed the arguments that would later find their way into print. Starting from the premise that there are ‘two evils’, a universal preoccupation with sex alongside universal dread of its procreative consequences, her diagnosis was ‘a truly neurotic condition [expressed in] abnormal sexuality’.Footnote 99 Combining psychological analysis, with sociological insights on the wide recourse in marriages to ‘unnatural’, non-reproductive sexual acts (chiefly coitus interruptus and anal sex),Footnote 100 Dr Bieżanek takes as her lead ‘those spokesmen’ of the Church who piously diagnosed ‘recourse to the Virgin Mary’ for spiritual aid.Footnote 101 What follows is a schematic outline which would be later developed, with the historical Miriam of Nazareth held up as neither ‘model or guide’ not least because of St Joseph. Hailed as ‘certainly a marvel’ in his ‘profound respect for his spouse and self-effacement’,Footnote 102 she continued:

Mary’s virginity was in his keeping and he kept it … She had but one child and a husband who made no demands on her.Footnote 103

Developing out the dogma of Co-Redemptrix, alongside a low estimation of most men’s capacity for sexual restraint and selflessness,Footnote 104 she concluded her essay more trenchantly than her autobiography: ‘Men have had the running of the world until now and the world is all but lost. It will be saved again by women and through women.’Footnote 105 Without commenting on the essay’s admixture of theology and proto-feminism, Bishop Graser’s response three weeks later was short and direct: ‘The main thing on which your essays rests is the doctrine of Our Lady as Co-Redemptrix, however, and unfortunately this has been misunderstood.’Footnote 106 After critique of her assertions on the incarnation and atonement theology, he concluded ‘the essay rests on a false foundation, giving rise to mistaken conclusions … it would be inadvisable to distribute the essay since it would be misleading.’Footnote 107 Indeed, as Dr Bieżanek would herself come to realise,Footnote 108 in founding her vision of sex reform and female marital liberation (within discrete bounds, as she was a political and social conservative on other issues)Footnote 109 on an undefined teaching of the Church, her programme for reform and renewal remained captured within institutional logics and was scuppered, upon its birth, in a rapidly shifting theological scene.

The correspondence that Bishop and laywoman exchanged through the spring of 1963 mostly consisted of Dr Bieżanek updating ‘dear Eric’ on her Family Planning Training in Birkenhead and describing the Catholic women who came to her for help in fitting diaphragms without their husband’s knowledge. As she concluded in a letter in May:

Things that are done in sacred places are going to be shouted from the house-tops.

Do I need to add that you and Archbishop Heenan between you (and particularly the latter) are going to have a first class crisis on your hands?

Today is the Feast of the English Martyrs and I know what I am about. May I make this last appeal to you to meet me this month and discuss what is to be done for the best?Footnote 110

This appeal for mediation—which from the Bishop’s perspective probably meant greater discretion as well as desisting from opening the clinic—was unsuccessful. In a letter written in July, Dr Bieżanek opened with the statement ‘I know that to engage in a project of connivance with me would in fact be impossible, even if you wanted to. You will have to come out into the open, either for me or against me.’Footnote 111 In an emotional and evocative piece of writing that reads like the ‘95 theses’, she concluded:

So it will have to be the other thing: open war. … There is nothing personal in this, it is just the necessity of the situation. …

My declaration of war takes this form: I intend to run, from this house, a private clinic for the purpose of helping Catholics overcome their matrimonial problems. I do this on my own authority and stand between them and anything the clergy choose to say to them on the subject … I am not one little bit afraid of you or the machinery behind you. You will, all of you, break your teeth on me. … In order to get this over as quickly as possible, I wish you would advise me as to the minimum amount [sic] of public provocation I need to give you, to justify your public intervention.

A notice nailed to the Church door announcing the opening of such a clinic?Footnote 112

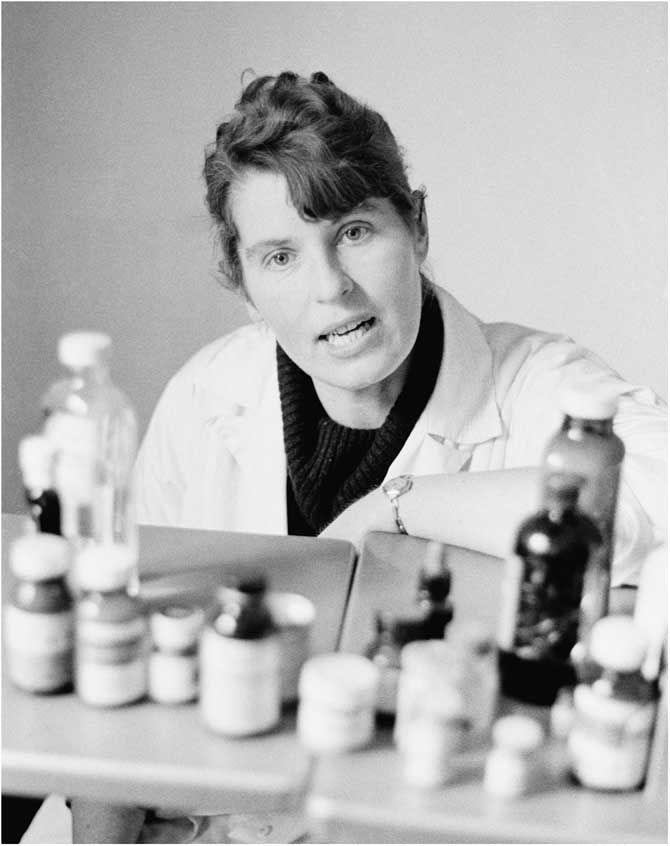

Even the opening of her clinic two months later in September, dedicated to Spanish mystic and healer St Martin de Porres and her reception of a stream of Catholic clients in the early months, did not itself openly constitute an ‘act of war’ (figure 2).

Figure 2 A confident, forthright Anne Bieżanek in her dispensary. Permission granted by Getty Images.

It was rather the report within November’s Daily Mail—with which this article opened—and a short interview on Granada TV’s ‘Scene at 6.30’, which prompted Canon Higgins publicly to refuse her Communion on 1 December 1963 with the loud, public statement ‘You don’t get it’.Footnote 113 In the weeks following, other parish priests similarly passed her over at the altar—Father McManus saying ‘pardon’ when doing so, and the Daily Mail reporting ‘crowds gathered around her when she left at the end of the service’, mostly to offer ‘support’ and ‘encouragement’.Footnote 114 These events were, however, the breaking point for her husband Jan—in All Things New she described his contentment with her contraceptive arrangements until ‘the public rebuff’, which he felt as a form of corporate shaming, branding her as a heretic, whore and sinner.Footnote 115 For Jan, as for Canon Higgins, it was the publicity—the airing in public of things that were ‘secret and sacred’—which elicited acts of outrage and vengeance. What also followed was a very public dissection,Footnote 116 an almost ‘kitchen-sink drama’ of their marital difficulties. The Daily Mail reported in January 1964 that ‘Husband drops Ultimatum on Clinic’,Footnote 117 only to be followed in May by ‘My marriage had broken up, says Birth Control doctor’.Footnote 118

Something of the same ‘keeping up appearances’ mentality was present in the Diocese’s position on the clinic and its proprietor, who were now firmly thrust into the media spotlight. In official correspondence to ‘my dear Mrs Bieżanek’, Bishop Graser reiterated the Church’s official line of retraction, repentance and restitution to make good the public scandal caused.Footnote 119 In correspondence exchanged in April 1964, following a suggestion that she could attend Mass and receive Communion in Churches in nearby Liverpool (which were not under Bishop Graser’s jurisdiction),Footnote 120 Dr Bieżanek expressed disquiet that it would be ‘wrong’ to ‘work a fiddle over territorial boundaries and take advantage of things that haven’t been said [publicly] by other Bishops’.Footnote 121 She concluded her correspondence by observing that: ‘it would involve me in what would amount to a conspiracy to treat you as an amiable lunatic … and dissimulate in order to protect [sympathetic] priests’ by putting the ‘letter of the law, on boundaries of authority, over the spirit.’Footnote 122 Implicit within her own phraseology, in its discussions of ‘lunacy’, is the ambiguity latent throughout the clerical correspondence and tabloid reports about Dr Bieżanek’s sanity, and whether her dramatic intransigence on this issue was vanity, mental instability or the prophetic voice of ‘Catholic modernity’. Speaking nearly fifty years later about a late evening conversation around April 1964 with the Bishop’s representative, Dr Bieżanek recalled:

He said: ‘No, we don’t want you closing, you mustn’t close your clinic’, [as] ‘we’d be accused of twisting your arm.’ And I said: ‘well, I sort of have a feeling you are, you know?’ And he said ‘well, you can’t possibly [close], no, no’. He said, he’d worked it out, he said the only think I could do … was that I … could go to Mass and seek Communion provided I wasn’t recognised. But if anybody told that priest ‘oh, there’s that woman’, they’d have to refuse me. … And I thought to myself, ‘do I want to be in communion with these guys? They’re absolute heretics, they’re ghastly! Ghastly’.Footnote 123

The body of Christ and women’s bodies: sexual politics in Westminster Cathedral

The duplicity and hypocrisy implicit in these clerically proffered, pragmatic solutions to her dilemma galvanized Dr Bieżanek’s last public and highly audacious gesture of defiance, which the New York Times described as ‘the most publicized and photographed mortal sin ever committed.’Footnote 124 Within the pages of All Things New, Dr Bieżanek described her earlier interactions with Archbishop Heenan through the 1950s, when he had charge of the See of Liverpool, which centred around her unsuccessful petitions for greater pastoral support for one of his priests under her psychiatric care.Footnote 125 In two colloquial pieces of correspondence to the Bishop of Shrewsbury in July 1963, she recounted a recent visit to Dr Heenan in Liverpool to discuss the soon-to-be-opened clinic and her bar from receiving Holy Communion. Describing a ‘more agreeable’ meeting than anticipated, alongside the Archbishop’s disclaimer of ‘jurisdiction over the whole of the North of England’,Footnote 126 Dr Bieżanek told Bishop Graser that ‘Dr Heenan [is] a bit jumpy’Footnote 127 and continued:

To understand that man on this subject you will have to realise that he knows a great deal more about me than I have every told you. He is in a jam and I don’t think he is certain of my new found benignity. Come to that, nor am I. It all depends on how I’m treated from now on. If I’m treated like a sensible person, the chances of me behaving like one are enormously increased.Footnote 128

It is against this backdrop of longstanding acquaintance and pre-existing enmityFootnote 129 that Dr Bieżanek wrote in February 1964 to Archbishop Heenan—now Archbishop of Westminster—to state the case for a public examination of the Church’s position on contraceptive practices. In plain terms she wrote:

It is my intention to force matters into the open in such a manner that others will have to share in thinking out a just solution; and such far reaching moral problems as are at present locked inside my own head (to my own considerable discomforture) should be presented for Universal Consideration.Footnote 130

Seeking to wash his hands of the matter by echoing his previous response that ‘my jurisdiction does not extend beyond the Diocese of Westminster’,Footnote 131 Dr Bieżanek’s responded wryly by ‘thanking him for [this] knowledge’ whilst throwing down the gauntlet: ‘Before May is out, I will have invaded your own diocese. May 31st may well see me presenting myself for Communion in your own Cathedral’.Footnote 132 As sex reformers before her had used public confrontations within ‘sacralised settings’—parliament, courtroom or Church—to publicise their cause, so too did Dr Bieżanek seek out a stage for this dramatic, climactic gesture.Footnote 133 Writing to the ever-tolerant Bishop Graser, Dr Bieżanek warned him to brace for the ‘hurricane’ of media publicity as she intended to ‘use all modern methods of communication to get the point across’.Footnote 134 As a postscript to the letter she added: ‘re John Carmel [Heenan], there is only one way of dealing with that boy and that is to thump him when he isn’t looking. He can take it alright—when it comes in that form.’Footnote 135

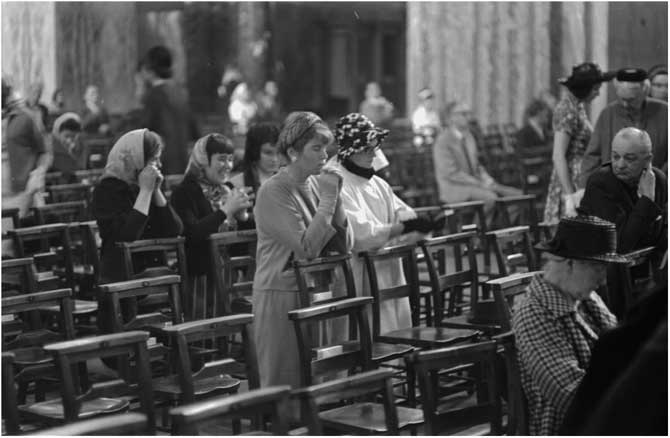

A generalized pre-emptive strike was issued by Archbishop Heenan, speaking for the entire Hierarchy of England and Wales on 7 May 1964, when he issued a pastoral directive reiterating that ‘contraception is not an open question’, whether by ‘pills’ or ‘contraceptive instruments’.Footnote 136 In this statement, the Bishops also condemned the doubts sown in the minds of the faithful ‘by imprudent statements questioning the competence of the Church in this particular question.’Footnote 137 Disquiet on these issues had been growing from multiple quarters, but Dr Bieżanek publically took up the fight three weeks later through her highly publicised (and photographed) reception of Holy Communion at Westminster Cathedral (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Confrontation in the Cathedral. Dr Bieżanek praying after receiving Holy Communion in Westminster Cathedral, Daily Express, 31 May 1964. Permission granted by Getty Images.

Having written to Archbishop Heenan to announce her intention to attend Mass and describing the clothes she would be wearing so as to be recognised—‘a blue coat and a blue hat’—she presented at the Communion rail on 31st May 1964. She had quite deliberately timed this attendance (and perhaps her wearing of blue), with the Feast of the Queenship of Mary and was given Communion by Canon Victor Gauzzelli. Archbishop Heenan was not present at the service. Speaking after Mass to the throng of reporters and television crews gathered outside the Cathedral, Dr Bieżanek accused Dr Heenan of being a ‘moral coward in not facing up frankly to my challenge’ and dismissed the Cathedral Authorities’ claims that they did not recognise her.Footnote 138 As she reasoned—‘a big fuss was made as I went into the cathedral, and … there were only a small number of people receiving Communion at the same time as myself. No mistake was possible.’Footnote 139 In her deliberately perverse interpretation of these events, her reception of the Blessed Sacrament was deemed a triumph and a sign that the unofficial head of the Catholic Church in England and Wales ‘now understands the dilemma of Catholics.’Footnote 140

Although she presented herself as a spokesperson for all Catholic women,Footnote 141 particularly those like herself who are ‘poor, in a straightforward way’ with a large Catholic family,Footnote 142 Dr Bieżanek’s activism did not enjoy the cross-class support of all Catholic laity. The Daily Mirror, for example, reported a small group of Catholics outside Westminster Cathedral who heckled her as she emerged from Communion, and in contrast to the saturated (and serious) reporting in the mainstream press, the Catholic newspapers did not widely cover the event. The Catholic Herald, similarly had run a hostile (and patronising) editorial in January 1964 entitled ‘The sad case of Dr Biezanek’Footnote 143 and on 5 June 1964 proffered a two paragraph factual piece under the banner ‘Dr Biezanek at Westminster’.Footnote 144 Meanwhile the more middle class, intellectual Tablet extraordinarily did not report on any of these happenings over six months, but ran theologically dense commentaries on the ambiguities of Church teachingFootnote 145 while merely carrying an advertisement for the book.Footnote 146 The Catholic Herald similarly tended to call upon CMAC doctors and educationalists such as Jack Dominion and Rosemary Haughton to write opinion pieces,Footnote 147 which they hoped would inform the impassioned and highly charged discussions of Catholics’ dilemmas in their correspondence columns.Footnote 148 In contrast, The Universe dodged discussion of the issue almost entirely—a stance endorsed by one correspondent (on behalf of Catholic parents) as this ‘delicate subject … is not suitable [for ventilation] in the columns of the most popular Catholic family newspaper.’Footnote 149 Dr Bieżanek’s media persona must therefore be placed in the broader context of a fascination within the secular press with radical and progressive claims of a ‘Church in crisis’.Footnote 150 As Sam Brewitt-Taylor has recently explored when analysing commentary on the Church of England, rhetorics of religious disintegration and sexual modernisation were not so much ‘discovered as invented’ in the early 1960s and Christians played a crucial role in the construction of this moral revolution.Footnote 151 There was, of course, also a sensationalist, gendered and anti-Catholic dimension to some of the reporting—a sense through most of the articles that the medieval mentality of Rome was being exposedFootnote 152 yet also a fascination with Dr Bieżanek and her candour, confidence and intractability which, as a commentator and former school colleague writing for the Family Planning magazine admitted, could be off-putting as it suggested her revelling in publicity.Footnote 153

Recalling these events herself from the distance of a lifetime, Dr Bieżanek felt shocked at her own audacity and summarized her early interventions in the birth control debate as the equivalent of the ‘little boy who’d shouted “the emperor has no clothes on”, you know, that’s really what happened.’Footnote 154 Dr Bieżanek’s refrain would be taken up in earnest, and monumentally amplified, four years later when many laymen and women, alongside some clergy, petitioned Rome and commandeered the media to voice their own disillusionment with the disjuncture between dogmatic teaching and ordinary, married practice. While her own cause célèbre was, as she admitted, a ‘nine day wonder’,Footnote 155 these confrontations in the press and the politicisation of the sacraments anticipated further confrontations in Churches across the country—wranglings in the confessional and a deluge of angry correspondence in letters’ pages following the leaked Majority Report and Paul VI’s encyclical.

Conclusion

In the opening pages to All Things New, Dr Bieżanek reflected on the public reaction to her clinic (and her highly-reported confrontation with the English Catholic Church) and rhetorically asked: ‘What is it that has prompted so many people to write to me, and to write in such moving and intimate terms, to me, a stranger?’Footnote 156 As an answer to this question in the pages that followed, she conjectured that it was ‘a revelation of a state of affairs that has always prevailed but has hitherto been nicely walled up behind the respectable façade of “Christian marriage”’.Footnote 157 In the letters reprinted, which themselves warrant an extended analysis, the voices of ordinary Catholics and, in particular, women who recounted the terrors of sex without contraception and the strains of multiple births are accessible, overcoming reticence and embarrassment. Congratulatory, colloquial, and often confessional, their tenor is exemplified in extracts such as: ‘you have made public a problem which has haunted women secretly for many a long year’Footnote 158 or ‘we use contraceptives and so do all my Catholic friends.’Footnote 159 Reminding the historian of sexuality of the letters penned by exhausted mothers and anguished husbands to another British sex reformer,Footnote 160 in the course of our conversations in Wallasey I asked Dr Bieżanek whether she had read Marie Stopes’ Married Love (1918), to which she responded ‘Yes, I did become, yeah, very impressed with it, very impressed with what they did.’Footnote 161 The distance travelled by British society and the English Catholic Church since Marie Stopes first set up her clinic in north London in 1921 and, technically, lost her libel suit against the Roman Catholic convert and medical practitioner, Dr Halliday Sutherland, is palpable.Footnote 162 Yet there are some surprising, counter-intuitive parallels which may be drawn, if All Things New is compared to Stopes’ A New Gospel to All Peoples—the latter inspired by a ‘prophetic dream’ in her garden in Leatherhead and delivered to the Anglican bishops at Lambeth in 1920 to persuade them of the divine sanction given to birth control.Footnote 163 Similarly, more comparisons emerge if viewed through the lens of the media and its capricious constructions of ‘femininity’, ‘professional status’ and ‘moral respectability’ projected onto the body of the female sex (or Church) reformerFootnote 164 —including the newspapers’ fixation with the fashion sense and copious auburn hair of Dr Stopes and Dr Bieżanek alike.Footnote 165

While it may tempting to view Dr Anne Bieżanek as a ‘Catholic Marie Stopes’, particularly in her fearless conviction and single-minded courage in tackling moral certitudes, Dr Bieżanek’s explicitly Catholic clinic in 1960s Wallasey dispensed the pill to her married co-religionists and ministered to a very different social and sexual landscape, including more developed cultures of sexual knowledge,Footnote 166 the near-contemporaneous establishment of the Brook Advisory Centre, the promotion of the ‘safe period’ through the Catholic Marriage Advisory Council,Footnote 167 and the longstanding infrastructure of the Family Planning movement. As Stephen Brooke has argued, ‘in the midst of the “secularization” of Britain, the Churches themselves became agents of permissiveness’Footnote 168 and the media clearly was another key player in conjuring and then sustaining a crisis of religion. Whether authored by John Robinson or Anne B-, newspapers conveyed a conviction of sexual modernity in the making.Footnote 169 This changed backdrop should also include a Church undertaking its own, perhaps belated, dialogue with a highly particularized construction of the ‘modern world’—an aggiornamento that would have consequences for the ways in which discourses and experiences of authority and the ‘primacy of conscience’ were refashioned in the years following the Second Vatican Council. And yet, the temptation to make comparisons with other British radicals and utopian sex reformers across the century remains. Recalling the support of local Liverpudlians when she again hit the headlines in 1993—this time for supplying cannabis (for therapeutic purposes) to her youngest, mentally ill daughterFootnote 170 —Dr Bieżanek’s son recounted that ‘people would ask how… mum was bearing up, and say “well, you know, we’ve always loved your mum ever since she gave the Pope a bloody nose!”’Footnote 171 So perhaps it is not a far stretch to situate Dr Bieżanek in a genealogy of those she celebrated in All Things New—single-minded, farsighted and slightly solipsistic mavericks on the fringe who sought to improve ‘women’s lot’ through female emancipation, the right to enter the professions, to own property and to exercise the vote.Footnote 172 Other querulous women, and some men too, who diagnosed the ‘birth pangs’ of a new social and spiritual order and were motivated by idealism but accused of iconoclasm.