The way in which the Madaba mosaic map and the ruins of the Byzantine structure were found, documented, and interpreted is crucial to understanding the differing views about the building's function and the map's meaning. The earliest reference to the discovery of a mosaic at the site appears in a letter that the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Nikodemos, received in 1884 from his representative in Madaba. It noted that a mosaic had been discovered by local Christians who were digging up the ruins of an ancient Byzantine structure in order to build a new church. The letter identified the Byzantine building as a church, explaining that the workers noticed the shape of a sanctuary in the remains. It was only in 1890 that Nikodemos’ successor Gerasimos commissioned the master-mason Athanasios Andreakis to inspect the floor mosaic and decide whether it should be kept in the new church. In fact, Andreakis paid little attention to preserving the mosaic map, which was fully revealed only once the new church of St George had already been built; according to a few testimonies, some damage to it occurred during the construction process. Kleopas Koikylides, the librarian of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate who came to Madaba in 1896, was the first to recognize the map's cultural and scientific significance. In 1897 he published the discovery, with Professor Georgios Arvanitakis from the Holy Cross School of Theology, who had been appointed by the Greek Patriarchate to measure and document the map.Footnote 1

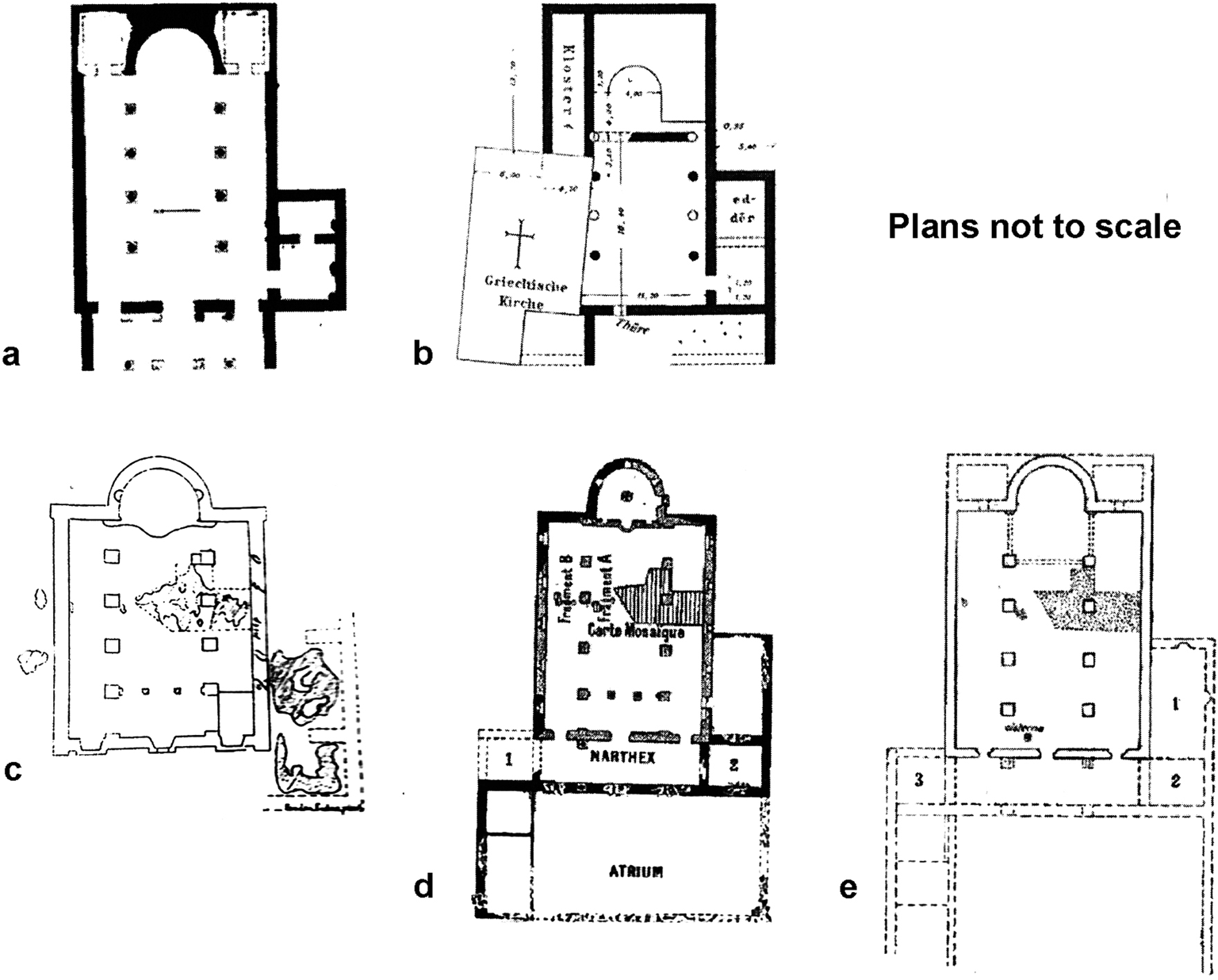

At that time, there was no doubt that the Byzantine building was a church, and between 1895 and 1899 five floor plans of the church were published: Frederick Bliss and Gottefried Schumacher published two different plans in 1895, shortly before the mosaic map was fully uncovered (Fig. 1a–b);Footnote 2 two other plans appeared in 1897 – one drawn by Georgius Arvanitakis for Koikylides’ publication, and a second published by Marie-Joseph Lagrange (Fig. 1c–d);Footnote 3 and a fifth plan was published by Giuseppe Manfredi in 1899 (Fig. 1e).Footnote 4 While these five plans differed in the shape of some architectural elements, they essentially reconstructed the same form of a church building composed of a nave with two aisles (separated from the nave by five-bay arcades), and with two side rooms projecting in the west end of the south aisle – a plan that basically echoed the floor plan of the newly built church of St George. The overlap between the two buildings was explicitly expressed in Lagrange's plan (Fig. 1d), the only one to distinguish between the Byzantine walls (coloured in black) and the nineteenth-century ones (marked by hatching). The observation that the two buildings overlapped was based on witnesses who noted that the two were identical in form, yet there were also witnesses who reported the opposite.Footnote 5 As Beatrice Leal has observed, the biggest discrepancies among the five plans relate to the eastern end of the building – discrepancies deriving from the fact that the eastern part of the Byzantine structure was covered in rubble when the plans were drawn – and as some of the Byzantine remains were removed during the construction of the new church and others covered by modern paving, it is impossible to verify the general shape of the Byzantine structure.Footnote 6

Fig. 1. a–e Five nineteenth-century plans of the building that housed the Madaba mosaic map: (a) from Bliss, ‘Narrative of an expedition’; (b) from Schumacher, ‘Madaba’; (c) from Koikylides, Ὁ ἐν Μαδηβᾷ μωσαϊκὸς; (d) from Lagrange, ‘La mosaïque géographique de Mâdaba’; (e) from Manfredi, ‘Piano generale delle antichità di Madaba’.

The mosaic map survived in four fragments. The main fragment (measuring about 10.5 x 5 m) depicts the area between the Jordan and the Nile (Fig. 2), and three small fragments include sites in the Upper Galilee and in the area of Lebanon: one represents the fortress of Agbaron (in the Upper Galilee), another contains a biblical phrase referring to the tribe of Zebulun as located next to Sidon (reflecting Gen. 49:13), and the third, which was lost at some point, represented the town of Sarepta (today Sarafand, located between Sidon and Tyre). The three plans that show the map within the Byzantine building – those of Koikylides/Arvanitakis, Lagrang, and Manfredi (Fig. 1c–e) – located the first three fragments in the places where they were incorporated in the new church: the main fragment is spread along the south end of the nave and the south aisle, the fragment of Agbaron is located in the nave's north section, and the Zebulon fragment is located in the north aisle, close to the building's north wall. The Koikylides/Arvanitakis plan seems to have also located the fourth fragment of Sarepta beyond the building's north wall, outside the church (Fig. 1c). It also shows three more mosaic fragments that were found outside the main building, locating them in what has been interpreted as the two side rooms outside the south aisle and in the equivalent area outside the north aisle (these three mosaic fragments depicted interlaced medallions, birds, and plants). Significantly, the Sarepta fragment and the fragment located close to the north wall of the north aisle provide an indication that the Byzantine building was wider than what has been reconstructed in the five floor plans, and, more significantly, that the complete mosaic map could not have fitted into the narrow church reconstructed in all of the plans (which reflect the measurements of the modern church of St George).

Fig. 2. The Madaba mosaic map, the main surviving fragment (including a small fragment that shows the town of Ashkelon), 10.5 x 5 m, sixth century (composite photograph by Eugenio Alliata; photograph courtesy of The Archive of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

The archeologist Michael Avi-Yonah, who in 1954 provided the first comprehensive analysis of the map,Footnote 7 proposed a revised floor plan that resolved the problem. Avi-Yonah accepted the observation that the Byzantine building was a church, and on the basis of some nineteenth-century testimonies and the three plans that showed the mosaic fragments, he reconstructed the church with a relatively wide transept, one that was broader than the nave and the aisles and could include the map's northernmost fragment of Sarepta (Fig. 3).Footnote 8 According to Avi-Yonah, together with the side rooms on both sides of the aisles, the width of the whole complex would have reached 30 metres – a width that accords more reasonably with the total extent of the map, which, according to Avi-Yonah's calculations, reached a minimum length of about 22 metres (more specifically: 24 m long by 6–7 m wide).Footnote 9 Avi-Yonah found a parallel for his reconstruction in the fifth-century basilica in Tabgha (known as the Church of the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes).Footnote 10

Fig. 3. A plan of the building that housed the Madaba mosaic map according to Michael Avi-Yonah (from Avi-Yonah, The Madaba Mosaic).

The Madaba map's site and scope: a renewed debate

In her recent reconsideration of the Madaba map, Beatrice Leal has pointed to the problematic situation implied by the five nineteenth-century plans and the unavoidable conclusion that the complete map could not have fitted into the narrow building. However, she ignores Avi-Yonah's plan, which resolves the issue: Avi-Yonah's research is mentioned in a note listing publications that reprinted the Koikylides/Arvanitakis plan,Footnote 11 while his own plan is just referred to as an ‘alternative plan’ to her own reconstruction in another note, without any discussion.Footnote 12 Leal has suggested a new reconstruction which, in fact, provides a solution similar to that offered by Avi-Yonah: ‘the map originally decorated a transverse hall at right angles to the nave of the current church’, and this hall measured about 25 metres (the measurement of 25 metres is given in her fig. 10, p. 135, which provides a reconstruction of the building).Footnote 13 The large measures of that hall and her observation that the mosaic map could not have fitted ‘iconographically’ into a church settingFootnote 14 lead her to propose that this hall might have served secular functions, either as a ‘residential audience hall’Footnote 15 or as a hall in a ‘public institutional structure’;Footnote 16 a hall for judicial hearings seems to her ‘a plausible context’.Footnote 17 Intriguingly, Leal observes that the nineteenth-century authors interpreted the Byzantine building as a church since this is what they were expecting to find, apparently because of their Christian backgrounds;Footnote 18 yet, on the basis of ‘Koikylides and Arvanitakis's belief that there were two phases to the building’,Footnote 19 she suggests that at some point during Late Antiquity the building was converted into a church. She does not explain why and when the change took place (her suggestion of both phases is shown in her fig. 10).Footnote 20

I have some doubts about Leal's interpretation. To begin with, I take issue with her argument about the ‘possible secular identifications’ of the hall in which the floor mosaic map was displayed.Footnote 21

Her claim that the hall might have served for legal hearings is based on three arguments. First, she asserts that ‘the associations between gates and justice documented in the Old Testament seem to have persisted well into the early Middle Ages in both East and West’; the location of the hall with the map just inside Madaba's northern gate, she claims, supports the argument for such activity there.Footnote 22 Second, ‘the sheer number of inscriptions on the Madaba floor – unprecedented in mosaics from domestic contexts – would be appropriate to a judicial setting’.Footnote 23 Third, she notes ‘the prominence given to the names and territories of the twelve tribes, which emphasizes the ownership and allotment of land’.Footnote 24 According to Leal, the definition of the boundaries and the borders between the tribal domains not only expresses ‘one of the most common points of civil legal disagreement’,Footnote 25 but the emphasis given to the names of the tribes on the map relates to broader concepts of law and judgment as given in the New Testament (where the tribes are associated with the twelve apostles and their role in the Last Judgment) and in some early Christian writings. In her words:

little is known of the interiors of late antique and early medieval courtrooms, but in eleventh-century Constantinople a hall used for judicial tribunals is recorded as having been decorated with a mural of the Last Judgment. It is possible to imagine that the mosaic map, which displays the allocated lands of the twelve tribes of Israel, fulfilled a comparable function as a historical example of heavenly justice enacted on earth.Footnote 26

This argument can be refuted on several counts.

As Leal herself notes, we don't really know what imagery decorated late antique courtrooms. Therefore, one may find the comparison she suggests – a mural depicting the Last Judgement in an eleventh-century judicial tribunal – insubstantial for arguing that the delineation of the tribal domains on the Madaba map stood for the Last Judgment, and (thus) that the building functioned as a judicial hall. Nonetheless, even if the delineation of the tribal domains on the map was intended to embody the concept of Heavenly justice as established in the New Testament, it inherently reflected a religious concept, and that means that it was also quite appropriate for a hall with a religious context. Moreover, the focus on the inscriptions relating to the boundaries and the tribes alone overlooks the comprehensive narrative constructed on the map by the range of inscriptions. As will be shown below, the six types of inscriptions constructed a complex religious narrative that not only suited a church building, but conveyed the same message as the biblical imagery used in early Christian churches.

In discussing the map, the understanding of its original appearance as a complete work must be taken into account. Different views have been expressed regarding the extent of the map in its complete state. Observers of the map at the time of its discovery (and before parts of it were destroyed during construction) testified to having read the toponyms ‘Smyrna’ and ‘Ephesus’.Footnote 27 Avi-Yonah rejects this testimony, doubting that ‘the villagers of Madaba in the eighties could decipher correctly the difficult writing of the map’,Footnote 28 and since Eusebius’ Onomasticon – an alphabetical gazetteer of places mentioned in the Scriptures, compiled by Eusebius (c. 260–c. 340) in about 293 and translated into Latin by Jerome in late fourth century – appears to have been the main literary source of the map, Avi-Yonah suggests that the original boundaries of the map followed that text, i.e., from Byblos, Hammat, and Damascus in the north to Mount Sinai and Thebes in the south.Footnote 29

Leal holds the opinion that the map included the region of Asia Minor.Footnote 30 She goes against Avi-Yonah and others’ dismissive attitude towards the ‘villagers of Madaba’, and on the basis of Arvanitakis’ testimony that those who saw the map immediately after its discovery ‘claimed that the whole floor of the church was covered by the mosaic map and included not only the whole of Palestine but also Syria, Egypt, Asia Minor, the islands of Cyprus, Crete and even the city of Rome’,Footnote 31 she suggests that the map presented the entire region of the Eastern Mediterranean with the town of Madaba – which was apparently marked on the part of the map that has not survived – in the exact centre (a reconstruction of such a map, depicting the area from Turkey to the Red Sea including the regions of Mesopotamia and Arabia, and the islands of Crete and Cyprus, appears in her fig. 11, p. 136). It should be noted, however, that Arvanitakis’ testimony, on which Leal's reconstruction is based, explicitly states that those who saw the map claimed that ‘the whole floor of the church’ was covered by the map.Footnote 32 Therefore, if we take this testimony as a reliable source for reconstructing the extent of the map, we should reconstruct it as covering the floor of the entire Byzantine building, not only its eastern part (as reconstructed by Leal and all others). I should also note that Leal quotes this very quotation, but omits the first words that refer to the entire floor of the church (in her words: ‘Altogether, viewers reported seeing “not only the whole of Palestine but also Syria, Egypt, Asia Minor, the islands of Cyprus, Crete and even the city of Rome” on the map’).Footnote 33 In Leal's words,

the extension of the map to include the topography and political centers of the entire region can be taken as further evidence of a nondevotional function for the mosaic. In the central area, it was the territorial divisions of the Holy Land, rather than its holiness, that were chosen for display.Footnote 34

As will be argued below, the territorial divisions of the Holy Land played a role in both the creator's strategy of conceptualizing Palestine as a sacred space and in the religious narrative that the map constructed. I believe that even if some towns in Asia Minor were presented on the map, they would have been depicted at the margins. Moreover, it seems to me that the area in which Leal's reconstruction (her fig. 11) depicts the region of Turkey is the very area where the Sarepta fragment – not marked in this reconstruction – should appear (yet it does appear in her other reconstruction, which shows the position of the map within the wide hall (her fig. 10a, at 135). Put differently, the location of the Sarepta fragment in relation to the hall's north wall – whether this hall was a transept of a church or a hall with secular functions – leaves no space for the huge area of Asia Minor and Syria (in point of fact, Leal's reconstruction of the four surviving fragments within the hall (her fig. 10a) tells the same story as Avi-Yonah's reconstruction (here, Fig. 3), which leaves no room for Asia Minor). Therefore, Avi-Yonah's suggestion remains persuasive: it seems logical to assume that even if the map presented some faraway locales from Asia Minor in its margins, it essentially intended to illustrate the area of biblical Palestine as outlined in the Onomasticon.

Without archaeological evidence to determine whether the Byzantine structure was a church or a secular hall, we are left with the mosaic's internal evidence to interpret its meaning. The question of the building's function remains unanswered.

A new medium: a map of a sacred land

The Madaba map also poses a challenge to scholars due to the fact that there are almost no surviving cartographical artefacts from Late Antiquity, while the surviving evidence suggests that the Madaba map was a new type of cartographical representation. Basing his argument mostly on textual sources, Jesse Simon identified two principal traditions in Roman cartography: the administrative formae of land surveyors, which presented local areas in a purely textual form, and pictorial representations of local provinces and the inhabited world (the Oikoumene), which probably took the form of wall paintings.Footnote 35 The illustration of Sicily in the Vergilius Vaticanus (Cod. Vat. lat. 3225, fol. 31v, dating to AD 420) – featuring Aeneas landing at Drepanum – seems to represent the second type in a small format.Footnote 36 Yet, the few surviving pictorial maps from Late Antiquity testify to a third type: the road map. Examples include a map that might show some part of Spain in the so-called Artemidorus papyrus (first century BC),Footnote 37 the Dura Europos map (Paris, BNF, Gr. Suppl. 1354, no. 5, early third century) that shows the coast of the Black Sea, and the Tabula Peutingeriana (Codex Vindobonensis 324), a twelfth-century copy of a fourth-century map depicting the route network of the Roman Empire.Footnote 38 This type of map seems to have served a variety of purposes: while the map in the Artemidorus papyrus was part of a composite work that presented the whole world, the Dura Europos map was perhaps painted on a shield of a soldier, and the Peutinger map might have been designed for propagandistic purpose and display in a throne room.Footnote 39

The Madaba map too was designed for public display, but it was a different type of representation. It provides a pictorial depiction of a land with no roads marked at all. Yet, although roads were not delineated, their presence is reflected in the selection of places that appear on the map. According to Avi-Yonah, many of these places were indeed located along the major roads of sixth-century Palestine. In light of this, Avi-Yonah concludes that the author of the Madaba map relied on a Roman road map.Footnote 40 This is a significant insight: it suggests that not only did the author of the Madaba map deliberately choose not to include the very feature that characterized Roman maps, but that he found this feature irrelevant to his own innovative map. On the other hand, what he did deem most relevant to his map were written inscriptions constructing a narrative for the land.

The link of the Madaba map to the Onomasticon has generated discussion regarding whether it reflects a lost ‘map’ of Judaea created by Eusebius to supplement his text.Footnote 41 It has also been suggested that the Madaba map was created on the basis of a lost map compiled specifically for pilgrims during the fifth century. Yoram Tsafrir, who developed this hypothesis, reconstructs both the content and appearance of this pictorial ‘lost map’, on the presumption that it was made in Latin and Greek versions and that copies were both used by pilgrims’ guides and bought by wealthy pilgrims as souvenirs.Footnote 42 The existence of a ‘pilgrims’ map’ at that time was uncontested and widely accepted.Footnote 43 However, since pictorial maps did not serve as a form of travel aid until the early modern period,Footnote 44 and more significantly, since we have no evidence that pilgrims actually carried maps, this suggestion must be rejected. Late antique (and later) itineraries were mostly in words alone (lists of places, stations and distances);Footnote 45 in the context of pilgrimage to Palestine, the Bordeaux pilgrim's account (AD 333) is a typical example of the genre of written itinerary.Footnote 46

The fact that the Madaba map was composed in the sixth century – when the consolidation of an idea of Palestine as sacred space had occurred and when a new type of iconography was developed to present the sacred topography of that land (as depicted on pilgrimage souvenirs) – suggests that this map was formulated out of the religious uniqueness of Palestine and was rooted in the religious uniqueness of that land.Footnote 47 That is to say that the Madaba map was not only a new type of cartographical medium – a regional map with no roads, as well as a map of a unique geographical entity, a sacred land – but also a new type of visual image, which can be considered to have belonged to the sixth-century innovative iconography of the loca sancta. Its four surviving fragments are enough to demonstrate the author's pictorial approach, as well as the very religious narrative that he constructed through a combination of topographical features and illustrative inscriptions.

Image and narrative

The landscape is evoked by the depiction of seas, rivers, streams, mountains, variety of settlements (towns, villages and fortresses) and holy places (marked by small edifices with red roofs that signify churches, Fig. 4), with an emphasis on Jerusalem, which is represented by the largest vignette on the surviving fragment. According to Avi-Yonah, Jerusalem was located at the exact centre of the map.Footnote 48 The inscription accompanying the vignette – ‘The Holy City Ierusa[lem]’ – underlines the city's sacred nature and uniqueness (it is the only place on the surviving fragments designated as holy), while the vignette itself is a product of a deliberate manipulation of the urban space: the Holy Sepulchre had been shifted south to be positioned exactly in the middle of the city, perpendicular to the cardo maximus, which has also been shifted to make a focus point with the church, exactly in the centre of the emblem; the Temple Mount is not depicted.Footnote 49 In essence, by highlighting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (through an authentic depiction) and by portraying the city filled with churches but with no reference to the Temple Mount, this emblem inherently characterizes Jerusalem as a Christian city and as the city of the Passion.Footnote 50 Notably, a variation of this vignette – which essentially conveys the same message – is found in another, later mosaic in the region, the mosaic of the eight-century Church of St Stephen at Umm ar-Rasas (in the Madaban diocese). Here too, Jerusalem is depicted as an encircled city in a bird's eye view, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is highlighted in the centre through a relatively large architectural symbol.Footnote 51

Fig. 4. Detail of the Madaba map, showing the holy places of Gilgal (‘Galgala’), Bethabara, and Bethagla next to the Jordan River.

The written element is the key to the religious narrative and message constructed on the Madaba map. Classifying the numerous inscriptions that appear on the map by the information they convey reveals the range of dimensions they evoke and add to the pictorial view, and is thus essential for understanding the map as a visual image and the narrative it constructs.Footnote 52 They can be categorized as follows:Footnote 53

(1) Toponyms. Most of the inscriptions contain bare toponyms; sometimes two or more toponyms are given to a certain place, yet sometimes it is emphasized that one of the toponyms is outdated (as, for example, ‘Aenon now Sapsaphas’ or ‘Bela also Segor now Zoora’).

(2) Holy places. The four surviving fragments identify fourteen of the holy places that they present (through architectural signs of churches) with toponyms. The following list represents them in two sections: the first includes holy places composed of tombs of saintly personages, and the second includes places associated with biblical events or personages (both sections are arranged in alphabetical order).

Tombs of saintly personages:

1. of Joseph

2. of Saint [Micah] (*the proximity of the inscription to Morashthi [mentioned in the next category, no. 5] implies that this inscription refers to the tomb of the prophet)

3. of Saint Zacharias

4. of the Egyptians (*three anonymous martyrs)Footnote 54

5. of Saint Victor (*an unidentified martyr)Footnote 55

Places associated with biblical events or figures:

6. Aceldama

7. [Arba] also the [Ter]ebinth. The Oak of Mamre

8. Bethabara of Saint John. The Baptism

9. Galgala also the twelve stones

10. Gethsemane

11. Here is Jacob's well

12. of Saint Elisha

13. of Saint Jonah

14. of Saint L[ot] (*the proximity of this reference to the Dead Sea implies its association with Lot and the narrative of Gen. 19)

(3) Biblical traditions. The surviving fragments include eleven inscriptions that associate specific places with biblical traditions. In alphabetical order, they read:

1. Ailamon where stood the moon in the time of Joshua the son of Nun one day

2. Desert where the Israelites were saved by the serpent of brass

3. Desert of Zin where were sent down the manna and the quails

4. Ephraim which is Ephraea there walked the Lord

5. Morashthi whence was Micah the prophet

6. Raphidim where came Amalek and fought with Israel

7. [of] Saint Philip. There they say was baptized Candaces the Eunuch (*marked by architectural sign of church building)

8. Rama. A voice was heard in Rama

9. Sarepta which is the long village there the child has been resuscitated that day

10. Shiloh there once the ark

11. Thamna here Judah sheared his sheep

(4) Tribes of Israel. Of the six surviving names, four are attached to phrases taken from three biblical chapters referring to the tribes – Jacob's blessing to his sons (Gen. 49), Moses’ blessing of the tribes (Deut. 33), and the Song of Deborah (Judg. 5):Footnote 56

1. Benjamin the Lord shall cover him and shall dwell between his shoulders

2. Zebulun shall dwell at the haven of the sea and his border shall be unto Zidon

3. Lot of Ephraim. Joseph, God shall bless thee with the blessing of the deep that lieth under, and again, blessed of the Lord be his land

4. Lot of Dan. Why did [Dan] remain in ships

(5) Milestones. Two references to milestones appear adjacent to Jerusalem, which seem to be explicit traces of the Roman road map the author used.Footnote 57

1. The fourth mile

2. The ninth mile

(6) Boundaries. Five inscriptions mark the boundaries of the land or of certain regions in both the Byzantine present and the biblical past.

1. Azmon city by the desert bordering Egypt and the going out of the sea (this inscription reflects the biblical description of the domain of the tribe of Judah as described in Josh. 16:3, but on the basis of the Onomasticon)Footnote 58

2. Beersheba now Beerossaba. Till which the border of Judea from the south from Dan near Paneas which bordered it from the north (the inscription refers to the boundaries of the promised land of the Old Testament [“from Dan to Beersheba,” e.g., 2 Sam. 3:10], but on the basis of the Onomasticon)Footnote 59

3. Border of Egypt and Palestine (the inscription refers to the borders of the Byzantine province of Palestina Prima)

4. East border of Judaea (this inscription derives from the Onomasticon [entry of Akrabim, 32], while “Judaea” means the land of Judaea as defined by Josephus)Footnote 60

5. Gerar. Royal city of the Philistines and border of the Canaanites from the south, there the slatus gerarticus (this inscription also reflects Eusebius’ words; slatus gerarticus was an administrative district of the Roman Byzantine period)Footnote 61

Though fragmentary, this list provides some insights. First, it reveals the crucial role played by the written component in inserting biblical content into the image. Second, it reflects the significance of the Old Testament in the image. Specifically, of the eleven biblical inscriptions (section 3), nine refer to episodes or personages from the Old Testament (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11), and of the fourteen labelled holy places that are marked on the surviving fragments (section 2), nine are associated with figures from the Old Testament (nos. 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14). The Old Testament environment is also constructed by the names of the tribes of Israel.

The biblical past was incorporated into the image also by a selection of pictorial symbols. Three of the holy places that are marked on the surviving fragments – the place where the Israelites crossed the Jordan and erected an altar of twelve stones (‘Galgala also the twelve stones’, section 2:9), the meeting place of Abraham and the three angels under the tree (‘[Arba] also the [Ter]ebinth. The Oak of Mamre’, 2:7), and the place where the apostle Philip baptized the Ethiopian ‘[of] Saint Philip. There they say was baptized Candaces the Eunuch’, 3:7 – are accompanied by symbols of stones, a tree, and a font (respectively): terrestrial features that embodied the biblical events in situ (as attested by the Onomasticon) and were translated into pictorial symbols evoking both the holy places and salvation history (Fig. 4).Footnote 62

Through these types of inscriptions and symbols the map not only ‘localized the holy’, to use Peter Brown's characterization of inscriptions on early martyr shrines in north Africa,Footnote 63 but created a condensed narrative for the land, with two apparent functions: to conceptualize the land as a sacred space and to convey a distilled religious message. In particular, through the manifestation of four types of localities – places of divine presence (on the surviving fragments: Ephraim and Shiloh, section 3: 4, 10); places of miracles (for example, the Desert of Zin and Sarepta, 3: 3, 9); places of the acts of biblical figures; and tombs of saintly personages – the map promotes the idea that the territory is a ‘trace’ of the sacred past and the place of the Revelation. Furthermore, by portraying Jerusalem as the city of the Passion, set among the domains of the Tribes of Israel and places associated with a variety of episodes from both Testaments, the map essentially expresses the theological idea of Fulfilment – the fulfilment of the Old Testament in the Passion of Christ. In other words, with its explicit Christian perspective – which is expressly conveyed in the vignette of Jerusalem – this map was an elaborated Christian visual image that urged one to view the land (and the scriptural references) through the lens of Christian theology and exegesis.Footnote 64

The Madaba map within early Christian religious art

In effect, with its typological narrative the Madaba map conveyed the very same message communicated by early Christian elaborated typological imagery (e.g. the fifth-century wooden doors of the church of Santa Sabina and the decorative programme of the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome), which juxtaposed scenes from both Testaments to illustrate ‘the continuity of divine planning, the harmony of the Testaments, and the salvational role of the Lord’, and which, in a sense, were visual commentaries on the Scriptures that enabled viewers to both comprehend and interpret them.Footnote 65 To use Jaś Elsner's words on the visual programme of the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, this arrangement was meant to reinterpret the Old Testament cycle ‘in terms of its fulfilment in the triumph of Christianity. It is not just that specific Old Testament themes prefigure the events from Christ's life, but that the whole narrative of Jewish history is presented as subservient to, completed in, the Incarnation’.Footnote 66 The Madaba map presents the very same fulfilment, but in topographical terms: it depicts Jerusalem as a purely Christian city set among a variety of Old Testament localities/events, while the central position of the Holy Sepulchre in the city vignette (and in the entire map) proclaims the fulfilment of the Old Testament in the Passion of Christ.

As an image that conceptualized Palestine as a sacred space and a physical manifestation of the sacred past, the Madaba map also corresponded with the sixth-century innovative iconography that figured on containers for sacred materials from the Holy Land. The surviving ones include some dozens of small pewter ampullae for oil and water (about 7 cm in height) and a wooden box (24 × 18.4 × 3 cm) that contains some stones and wood (the so-called ‘Sancta Sanctorum box’, Vatican, Museo Sacro, inv. 61883).Footnote 67 The interrelation between the map and this type of iconography lies in the strategy through which they conceptualize the Holy Land and the loca sancta, namely: by associating place with event and intimating that something from the sacred event could still be perceived at the holy place.

Specifically, the ampullae present a combination of visual depictions of sacred events and short captions referring to the depicted events; for instance, an ampulla of oil taken from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre depicts the Crucifixion and the women at the empty tomb on its two faces and bears an inscription that reads ‘The Lord is risen’. In this case, this combination of image and text essentially evokes the three past events that sanctified the place where the church was built (Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection), yet it also conceptualizes the place itself as a physical embodiment of these momentous events. The Madaba map suggests the very same conceptualization – of specific places and of the entire land – although through inscriptions and symbolic signs alone. There are ampullae that construct conceptual and spatial patterns similar to those found in the map. By showing scenes that are associated with different places – for example, an ampulla with the Adoration of the Magi on the obverse and a cycle of scenes including the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Baptism, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension on the reverse – the ampullae, like the map, did not simply concretize the absent past through a multi-episodic depiction, but suggested a ‘myth of completeness’.Footnote 68

The very same message is delivered by the Vatican wooden box using a combination of stones, labelled with inscriptions in Greek referring to their origins (the legible ones read: Bethlehem, Mount Zion, the Mount of Olives, and [the site of] the Resurrection), and a series of images that depicts five scenes from Christ's life on the inner side of the lid (Nativity, Baptism, Crucifixion, the women at the empty tomb, and Ascension).Footnote 69 The entire composition – labelled terrestrial relics and pictorial markers of certain events/sites, arranged in two adjacent framed rectangular spaces – conveys an emblematic reflection of the Holy Land through a selection of its most sacred places. We find here, as on the Madaba map, the formation of a spatial pattern through a careful selection of places – a spatial pattern capable of expressing the immanent sanctity of the topography of Palestine, of transmitting the faith in topographical terms, and of strengthening faith in God. It has been argued that the Vatican box's pictorial scenes were arranged as a chronological narrative in order to connect the user of the casket to the end of time, as it is the linear order that brings the distant (time and place) to the present of the user and allows one to ‘read his or her own time into a linear progression of the experience of elapsing time’.Footnote 70 The Madaba map provides the viewer with a non-linear narrative that leads one to the very same place. By presenting narrative pieces from both the Old and New Testaments alongside contemporary localities, the map produces a condensed but all-inclusive narrative that clearly concludes in the viewer's present. Yet by providing one with no roads to follow, the map encourages a spontaneous and contemplative movement along the narrative (including forward and backward) and a way to compose endless variations.

To conclude, the Madaba map was not simply a ‘map’, but rather an elaborate picture, a cultural product manifesting values of faith. By referring to an assortment of biblical episodes in relation to specific sites, the map localized the biblical past on earth, yet also embodied the principles of faith through the topography of Palestine. Through the representation of divine apparitions, miracles, and activities of saintly figures, this map was able to transmit a distilled religious message of unwavering trust in God, as well as the theological concept of Fulfilment. This map, therefore, was none other than a religious visual image.

The fact that this visual image was formulated in the sixth century – when Palestine had become a place of pilgrimage and its landscape had come to serve as a living geographical witness to the holy past – gives the raison d’être for the invention of the composition. In other words, the sacred nature of the land was the impetus behind the creation of this innovative map. In essence, the Madaba map – like the sixth-century Palestinian iconography of the holy places – was a means to conceptualize Palestine as a sacred space, a physical ‘trace’ of the sacred past.

Pnina Arad earned her PhD in visual studies from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Studying visual representations of the Holy Land, her recent publications include ‘Post-secular art for a post-secular age: stational installations of the Via Dolorosa in western cities’, Material Religion (2022), Christian Maps of the Holy Land: images and meanings (Brepols, 2020), ‘Landscape and iconicity: proskynetaria of the Holy Land from the Ottoman period’, The Art Bulletin (2018).