Introduction

From the beginning of the Hasanlu excavations in northwestern Iran in 1956, excavators recognized the eclectic nature of the material culture preserved in the destruction level of Period IVb (1050–800 bc).Footnote 1 The presence of imported objects, and of ‘foreign’ visual elements in locally produced objects, was immediately attributed to ‘Assyrianization’—defined here as the effects of the cultural hegemony of the Assyrian Empire,Footnote 2 centred about 300 km as the crow flies to the west of Hasanlu, a distance amplified by the Zagros Mountains. Believing that that local elites at Hasanlu were in the thrall of Assyrian visual culture, researchers asserted that elite artistic production was influenced by, or created in conscious emulation of, the monumental artistic production of Assyrian capitals. Accordingly, through ‘Assyrianization’, the local elite shared in the high status purportedly attributed to Assyrian culture at Hasanlu (e.g. Marcus Reference Marcus1989; Reference Marcus1996; Muscarella Reference Muscarella1980; Porada Reference Porada and Pope1965; Winter Reference Winter and Levine1977). This claim has been repeated so often that it has taken on the lustre of truth, rendering Hasanlu into an example par excellence of the phenomenon of Assyrian cultural dominance in the periphery (e.g. Gunter Reference Gunter2009, 49).

It is unquestionably the case that Hasanlu displays a mixed material culture before and during Period IVb. Artefacts found in the destroyed Period IVb citadel and contemporaneous burials provide evidence of the engagement of Hasanlu in broad networks of interaction. We are using the term ‘entanglements’ to describe these mixed archaeological materials in the particular sense defined by Phillipp Stockhammer (Reference Stockhammer2013, 16) as ‘the results of the creative processes triggered by intercultural encounters’.Footnote 3 This paper argues that the material entanglements present in the fusion of elements characterizing objects found at Hasanlu is not attributable to the passive reception or active imitation of hegemonic Assyrian culture, or that of any other neighbours (Figs. 1, 2). Rather, they are the material outcome of complex processes and relationships, a local response to particular pressures, in a specific social, cultural, and political context.

Figure 1. Aerial photograph and contour plan of Hasanlu, Iran. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Figure 2. Map of the region showing Hasanlu, Assyrian and Urartian capitals, and South Caucasian sites. Inset detail shows locations of ninth-century bc Urartian inscriptions. (Base map: Wikimedia Commons.)

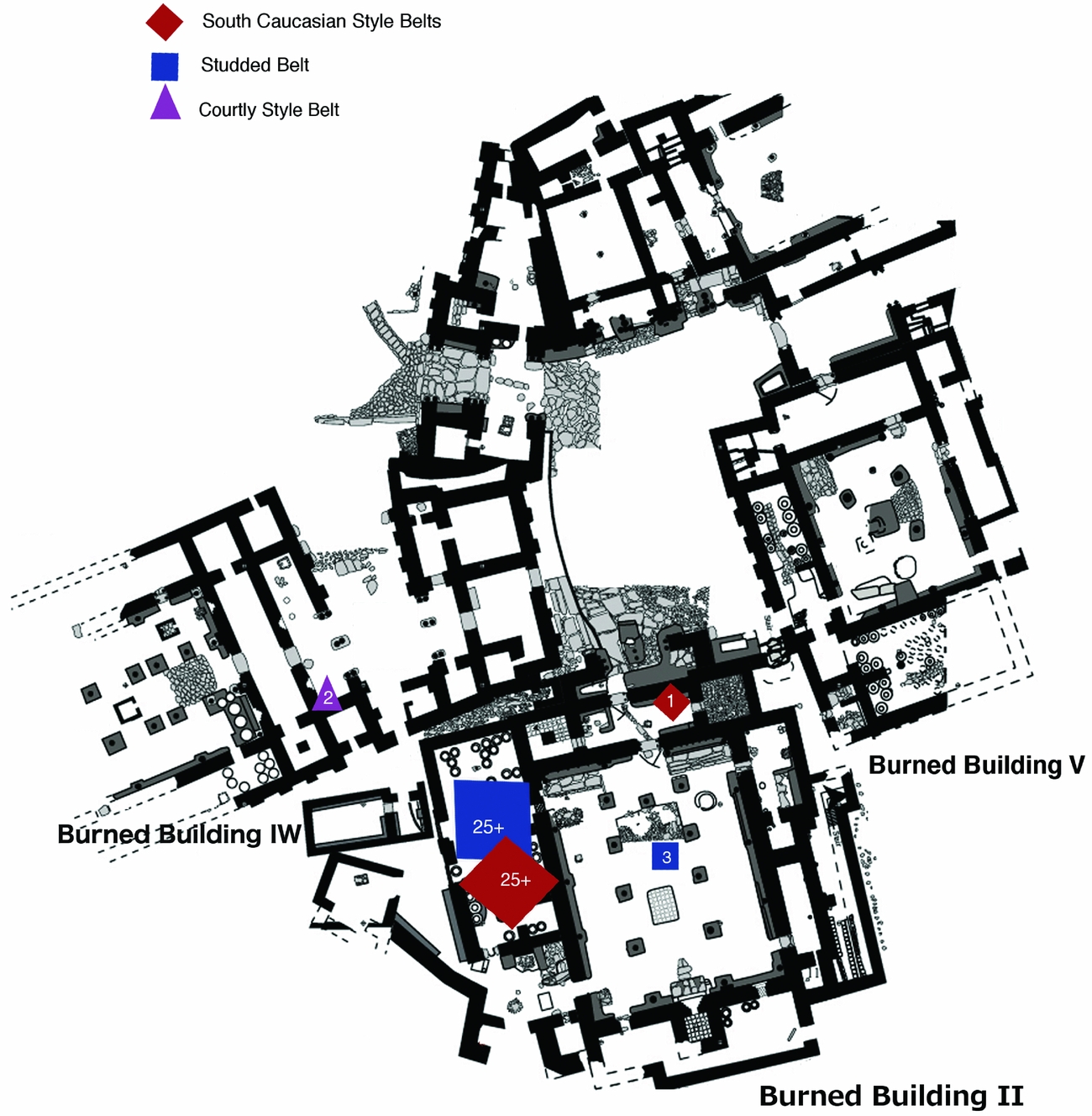

As a case study in mixed material culture, this paper analyses the use and transformation in Period IVb at Hasanlu of a South Caucasus artefact type originating hundreds of kilometres to the north: decorated sheet-metal belts. In three elite male burials and in structures on the citadel (Fig. 3), excavators uncovered fragments of nearly 100 examples of armoured belts articulated in styles ranging from the utilitarian and mass-produced to rarer, finely crafted exemplars. The geographical origins of the visual and technical elements of these belts serve as a starting point for the exploration of the materiality of intercultural interaction. This paper considers the utility of the concepts of ’hybridization’ and ‘heteroglossia’ in probing the transformative processes that take place in a local crucible where disparate visual elements, materials and ideas about the world react to and perturb each other, ultimately forging new social relationships and meanings.

Figure 3. Plan of the Period IVb (1050–800 bc) citadel at Hasanlu, Iran. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Beyond Assyria: Hasanlu in its regional context

In hindsight, it is not difficult to tease apart factors contributing to over-estimation of the role of Assyria and its material culture at Hasanlu. The excavators knew Assyrian materials well, and Assyria was widely viewed as the primary complex civilization in the region. In the midst of the Cold War, excavators at Hasanlu had limited knowledge of Soviet excavations in the southern Caucasus and the Caspian littoral, an enormous and disparate region now known to have enduring ties to northwestern Iran (e.g. Piller Reference Piller, Mehnert, Mehnert and Reinhold2012). This vast mountainous region encompasses parts of eastern Turkey, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and was home to fortress-based polities in the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages (Khatchadourian Reference Khatchadourian, Steadman and McMahon2011, 476; Smith Reference Smith2015, 154–83). In the century leading up to the destruction of Hasanlu, the area around Lake Van in eastern Turkey witnessed the maturation of the fortress-capitals of the kingdom of Urartu, a territorial state that would halt, temporarily, the expansion of Assyria in eastern Anatolia and Iran (Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Steadman and McMahon2011). The inability to recognize South Caucasian traits in the materials found at Hasanlu magnified the importance of the few recognizably Assyrian objects to narratives about cultural development and change. This factor, amplified by the (often implicit) application of world-systems theory to the relationship between highly complex and literate Assyria and smaller, unlettered Hasanlu encouraged excavators to construe a hierarchical relationship between Assyria and Hasanlu, whereby Hasanlu was the ‘periphery’ to Assyria's ‘core’ (Cifarelli in press a).

Axiomatically related to the paradigm which casts Hasanlu as peripheral to the Assyrian core is the pervasive, colonialist assumption that the seeping of sophisticated Assyrian culture into that of Hasanlu was both natural and inexorable due to the ‘desire to match the cultural status of the [Assyrian] center’ (Marcus Reference Marcus1996, 49).Footnote 4 This framework for understanding cultural contact and its products has been largely debunked in recent years, even in contexts that conform more closely than Hasanlu does to the model of a colonized subaltern.Footnote 5

Finally, the attribution of mixed materials to Assyrian hegemony stems from a particular art-historical approach that investigates objects produced through cultural contact by tracing visual elements to a point of geographical or chronological origin. Modes of transmission are then investigated, relationships between the origin points and sites of mixed cultural production posited, a phenomenon exemplified by claims that Assyrian objects found at Hasanlu were royal gifts (e.g. Muscarella Reference Muscarella1980, 148–9). This focus on discovery of origins carries with it the assumption that the ancient conception of the ‘shape and meaning of the surrounding world’ (Maran Reference Maran and Stockhammer2012, 62) mirrors that of the scholar. In the absence of evidence of a direct relationship between Assyria and Hasanlu, our scholarly identification of objects or visual elements as being Assyrian in origin does not allow us to conclude that the residents of Hasanlu would have viewed them as particularly ‘Assyrian’ or as connoting what we understand about Assyrian imperial hegemony.

Recent examinations of the archaeological record of Hasanlu show that the number of Assyrian objects at the site is small, and they are found almost exclusively in temple treasuries (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti, Cifarelli, MacGinnis, Greenfield and Wicke2016). Hasanlu was well beyond the periphery of the Assyrian Empire during Period IVb (1050–800 bc), and its artisans were not likely have had access to monumental Assyrian imagery of the mid–late ninth century. Recent analysis of the aspects of Hasanlu's visual culture formerly ascribed to emulatory ‘Assyrianization’ suggests that such similarities can be ascribed to a shared Bronze Age visual heritage accessible to artists across the Near East (Cifarelli in press a).

During Period IVb the network of fortress-based polities in the South Caucasus and northwestern Iran was becoming much denser, and by the ninth century bc the Lake Urmia region was in the throes of annexation and colonization by the burgeoning kingdom of Urartu in the northern highlands (Biscione Reference Biscione2009; Danti Reference Danti2014, 802–3; Kroll Reference Kroll2010, 21–2; Piller Reference Piller, Mehnert, Mehnert and Reinhold2012, 305–6). Rather than viewing the eclectic culture of Hasanlu IVb as demonstrating the conscious or unconscious desire of the local elite to bask in the reflected glory of Assyria or emulating the material culture of the South Caucasus,Footnote 6 we will examine its production in relation to local agents negotiating changing power structures and identities in the shadow of Urartu.

Hybrids, hybridization and heteroglossia

The archaeological record of the Period IVb burials and citadel contexts at Hasanlu displays varying degrees of material and social entanglements linking the site to a wide range of cultures, including Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran and the Caucasus. Evidence for cultural mixing ranges from the local use of ‘foreign’ objects, to locally fabricated ‘imitations’ of foreign object types, to the skilful and nuanced blending of diverse traits in individual objects. Each of these three categories of mixing appears within the corpus of armoured and decorated sheet-metal belts found at Hasanlu. Building upon earlier research that traced elements of objects from Hasanlu to their origin (e.g. Muscarella Reference Muscarella1980, 1–2; Winter Reference Winter and Levine1977, 375–7), and moving away from their implied unidirectional ‘acculturation/assimilation/emulation’ model, this paper applies the theoretical concepts of hybridization and heteroglossia to the task of considering the interdependence of different elements of Hasanlu's society and the role of objects in negotiating power dynamics.

At the heart of this discussion is an attempt to understand the ways in which human interactions produce mixed material culture, processes that have been described using a wide range of terms.Footnote 7The terms ‘hybrid’ and ‘hybridity’ are ultimately derived from the realm of biology, wherein a hybrid is the offspring of parents of different species or types. The quasi-scientific neutrality of this term, however, is belied by its historic application to racial mixing, particularly in the colonial contexts in which it has been used as a proxy for regressive notions of a purportedly dangerous ‘devolution’ in opposition to racial ‘purity’ (e.g. Jiménez Reference Jiménez2011; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Riva and Vella2006; Young Reference Young1995). The use of ‘hybrid’ to connote a cultural mixture still, to some degree, carries these derogatory, colonialist overtones, a sufficient reason to avoid it.

To refer to cultural mixtures as ‘hybrids’, moreover, implies that their constituent components are somehow culturally ‘pure’ or essential (Gilroy Reference Gilroy1993; Silliman Reference Silliman2015; Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2013; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Riva and Vella2006; Werbner Reference Werbner2001). This problem of essentialism is particularly sticky when considering archaeological materials, because the very ontology by which art historians and archaeologists define and discern the cultural attributes of artefacts—typological studies and taxonomic schemes—reifies the ‘purity’ and boundedness of cultural categories (Langin-Hooper Reference Langin-Hooper2013, 100–103). The concrete products of cultural interaction, deemed ‘hybrids’ because they defy easy categorization, are often broken down into ‘pure’ traits with particular origins (Maran Reference Maran and Stockhammer2012, 63–4). The elements that comprise ‘hybrids’, however, are not things with neat edges that we can study in isolation, their meanings immutably fixed to their ‘pure’ point of origin. Rather, as Stockhammer suggests, the terms ‘pure’ and ‘hybrid’ are conventions, useful primarily as points on opposing ends on a spectrum of entanglement (Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2013, 12–14).

When investigating the material products of cultural contact, it is reasonable to begin by asking what are the salient traits? And, where do they come from? The answers to these determinative questions, however, privilege the ‘hybrid products’ of cultural contact, without illuminating the emergent social meanings of these objects (Maran Reference Maran and Stockhammer2012, 59–60). Further interrogation of circumstances of production and use, probing how and why new forms have come into being, moves us toward recognition of the ‘underlying differential relationships between the various social and economic groups . . . and the associated power dynamics’ (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Riva and Vella2006, 143) that contribute to the cultural amalgamation. Through careful attention to the micro-contexts of their emergence, and the identities and viewpoints of the decision-making agents, we can begin to see the transformative processes of hybridization by which material forms are integrated in contact situations (Maran Reference Maran and Stockhammer2012; Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer and Stockhammer2012).

A framework for asking how and why is found in the early twentieth-century philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin's consideration of the hybridity of expressions or ‘utterances’. Bakhtin asserts that all cultural discourse—including material culture—is characterized by heteroglossia, the coexistence of multiple voices or viewpoints in a single act of expression, or hybrid utterance (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1992, 291). The meaning of this hybrid expression does ‘not simply derive from a fusing of disparate elements, each bearing its own fixed cultural meaning’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2001, 136). Rather, Bakhtin suggests that the particular processes involved in hybridization—the answers to the questions how and why—engender new meanings, even as they can evoke older ones.

Extending Bakhtin's notion of hybrid utterance, post-colonial humanist Homi Bhabha examines the impact of power inequalities among the disparate viewpoints contributing to hybrid cultural discourse in colonial contexts, directly challenging colonialist assumptions regarding the unilateral flow of culture from civilizing colonizers to the receptive subalterns. His conception of an ambiguous, ambivalent ‘third space’ for cultural production provides room for agency, creativity, and even defiance (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994). This understanding of hybridization describes the creation of new forms of material culture that participate in the construction of complex relationships between cultures. Our consideration of heteroglot material culture can thus illuminate ‘the subversive, counterhegemonic discourses inherent in mixed forms’ (Liebmann Reference Liebmann and Card2013, 40).

Bakhtin and his followers distinguish between instances of hybridization that are organic (i.e. unconscious), in which disparate elements are combined unintentionally, and those that are intentional (i.e. conscious), by which colliding viewpoints are deliberately contrasted or ‘set against each other dialogically’ (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1992; Werbner Reference Werbner2001, 136). If we consider unconscious and deliberate hybridization as points along a spectrum of mixed utterances, we can loosely map them onto degrees of intercultural entanglement or mixing evident in the archaeological record. Bakhtin's organic, unconscious hybridity correlates archaeologically to the presence of a ‘foreign’ object used in a new cultural context—the initial material interaction is not necessarily produced intentionally, but is nonetheless meaningful. The organic shift in meaning that occurs when even an unaltered object appears in a new cultural context is a form of hybridization characterized by Stockhammer as ‘relational entanglement’. Bakhtin's intentional, or conscious hybridization, on the other hand, correlates archaeologically to new forms that combine and contrast elements of the disparate cultures in contact, a phenomenon referred to by Stockhammer (Reference Stockhammer2013, 16–17) as ‘material entanglement.’ In order for this more conscious hybridization to take place, we do not need to assume that the local human creators were purposefully crafting the particular admixtures that contemporary scholars can detect in the material record. Nor do we presume, as the traditional acculturation models have, that the integration of exogenous visual culture into local production is a form of emulation that reinforces the hegemony of the point of origin. However, at the more deliberate end of the spectrum of material engagement, when hybridized forms are inserted into or replace the dominant cultural discourse, they provide an opportunity for ‘the audience to resolve its ambiguity’ about contact between cultures (Van Valkenburgh Reference Van Valkenburgh2013, 309), particularly in cases where one culture is perceived as posing an existential threat to the other. Understanding that hybridization is an ongoing process by which heteroglot, multivocal utterances can both express and resolve power differentials broadens the epistemological scope of our investigation. We can proceed from the identification of the origins of design, styles, and materials to interpreting their participation in the ‘active construction of identities on the ground in contact situations’ (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Riva and Vella2006, 139).

This post-colonialist approach to the interpretation of mixed forms has been applied productively to the study of material culture produced through encounters that conform in varying degrees to models of colonialism (Gosden Reference Gosden2004).Footnote 8 The fraught cultural encounter between Hasanlu and Urartu is colonialist in the broadest sense of word, operating within what Chris Gosden calls a ‘(partially) shared cultural milieu.’ In the early first millennium bc, Hasanlu and the emergent state of Urartu shared cultural attributes, and may not have viewed one another as entirely alien ‘Others.’ With their historical connections to the South Caucasus during the course of Period IVb, the residents of Hasanlu would have been alert to the coalescing of the Urartian kingdom in the highlands, and its development into a power that ended Assyrian raids into their neighbourhood. By the late ninth century bc, archaeological and historical evidence indicates that numerous sites near Hasanlu were under Urartian control (Danti Reference Danti2011, 14; Dyson & Muscarella Reference Dyson and Muscarella1989, 17; Kroll Reference Kroll2010, 21–2; Reference Kroll2013, 185). Throughout the course of Period IVb at Hasanlu (1050–800 bc), well in advance of historical manifestations of the emergence of the Urartian state, there is archaeological evidence at Hasanlu for an awareness of an impending external threat. The previous period (IVc) ended with the destruction of the citadel by fire that was likely military in origin. Throughout Period IVb, architectural shifts created a defensible core of monumental buildings, including the repurposing of structures at the heart of the citadel as stables (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli, Cunningham and Driessen2017a). The material culture of the Period IVb citadel skews towards militarism, and newly introduced military materials are markers for gender and status differentiation in the nearly 100 contemporary burials (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli2016; Reference Cifarelli, Cifarelli and Gawlinski2017b), burials that include a potential migrant warrior from the north (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015). Aggregated, these shifts suggest that throughout Period IVb—well before the state of Urartu manifests itself historically in inscriptions and fortresses—Hasanlu was alert to the immediate threat of political and military domination from the north. It is possible that the resistant and resilient nature of Hasanlu's response to the threat of Urartu precipitated its brutal destruction (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli, Cunningham and Driessen2017a).

Metal belts at Hasanlu: a case study in mixed material culture

Through an examination of the copper-alloy sheet-metal belts found at the site, we argue that hybridization in the visual culture at Hasanlu occurred as the site entered into an increasingly intense dialogue with northern entities emerging as the kingdom of Urartu. While the use of copper alloyFootnote 9 has a deep and lengthy local history, appearing in the early Bronze Age burials of Period VII (early third millennium bc), copper-alloy belts do not appear until Period IVb. Sheet-metal belts originated in the highlands to the north, where they occur with great frequency and in an astonishing variety of decorative styles in late Bronze and early Iron Age contexts (e.g. Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017). During Period IVb, belts appear in three burials, and fragments of dozens more were found on the citadel. Most of these belts occur in three decorative styles, each of which is represented in a single burial and a distinct citadel context. While all metal belts at Hasanlu are products of interactions between the residents of Hasanlu and their northern neighbours, these distinct classes of belts evince particular cultural mixtures created through different processes and degrees of hybridization, with consequent differences in semantic and social potential.

The history and distribution of copper-alloy belts in the northern highlands: the South Caucasus and Urartu between the thirteenth and seventh centuries bc

Excavated examples of armoured belts made of sheets of copper alloy and decorated in a broad array of styles, from simple embossed geometric decoration to elaborately incised figurativel scenes, first appear in an area stretching from Georgia's Black Sea coast, through North Ossetia in Russia, eastern Armenia and western Azerbaijan as early as the thirteenth century bc (Fig. 2). In this region, metal belts occur with such frequency that we cannot interpret them as elite items.Footnote 10 They appear slightly later in the Talesh region along the Caspian coast (Papuashvili Reference Papuashvili, Mehnert, Mehnert and Reinhold2012, 65–78) and in northern Iran (Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017, 10–12). The belts found at Hasanlu provide the only excavated attestation of their use in the Lake Urmia basin.Footnote 11 While in South Caucasian inhumations belts are generally found in situ at the waist, this is not the case at Hasanlu, where they are buried alongside, rather than on, the body.

Metal belts would also become an important component of Urartian material culture, the earliest (eighth century bc) examples found near the fortress of Erebuni in Armenia. This location for their occurrence is not coincidental—Urartians appear to have integrated metal belts into their material culture following the Urartian conquest of lands north of the Araxes River. Urartian sites have yielded, in addition to a small number of elegantly decorated figurative belts (e.g. Martirosjan Reference Martirosjan1964, pls. 25–27; Tasyürek Reference Tasyürek1975, fig. 18),Footnote 12 far larger quantities of simpler, more utilitarian styles (Barnett Reference Barnett1963, 161 & figs. 30–31), as well as South Caucasian belts of a type considered Proto-Urartian (Rubinson Reference Rubinson, Fahimi and Alizadeh2012b). In these Urartian contexts, as was the case at Hasanlu, belts are found near, but not on, bodies in burials (Rubinson Reference Rubinson and Kroll2012a). In Urartu, then, the indigenous South Caucasian convention for the crafting and wearing of decorated sheet-metal belts continues and expands, with the addition of new types decorated in the emergent style and iconography of the Urartian state assemblage (Zimansky Reference Zimansky1995).

Metal belts at Hasanlu: imports and innovations

The Hasanlu Expedition recorded approximately 94 sheet-metal strips identifiable as belts or fragments of belts. Of these, four strips (one of which is probably not a belt) were found in burials in the Outer Town area and 90 other examples in the destruction of the citadel. At 2–3 mm thick, roughly the same as armour scales found throughout the ancient Near East, they would have been able to provide some protection if worn in battle, particularly if backed by leather (Hulit Reference Hulit2002, 125–33). The area of the body that they could protect, although limited, is vital, and such belts are widely regarded as a form of military equipment (Rubinson Reference Rubinson and Kroll2012a,Reference Rubinson, Fahimi and Alizadehb). However, excavators did not find any of these belts or fragments at the waist of the local and enemy combatants who were crushed as the citadel buildings collapsed in the midst of a brutal battle, a likely moment for wearing armour.

Rather, on the citadel belts and fragments were found in store-rooms and treasuries. More than 70 belt fragments appear amidst the rich and diverse collections in the temple treasuries adjacent to the main hall of temple BBII, and more were discovered in the collapse of first-floor store-rooms into BBII's main hall. In elite residences BBIW and BBIII, belts had fallen from first-floor store-rooms along with masses of objects including metal and ceramic vessels, furniture and personal ornaments. The presence of the belts in temple and elite residential collections, combined with their absence from bodies engaged in battle, suggest that at Hasanlu these belts were not worn as battle armour, but were used as emblems of militarism, whether worn ceremonially, displayed, or given as offerings to a deity. Without suggesting a direct link, we note that this interpretation accords well with the Homeric zoster, an armoured belt connoting military prowess worn by warrior-kings (Bennett Reference Bennett1997, 67–102; Lee Reference Lee2015, 137–9), and which appear as votive objects at sanctuaries in the early Iron Age in Ionia and the Greek mainland (Bennett Reference Bennett1997, 46, 52). As in the case of the ‘shining’ belt that accompanied the aged warrior-king Nestor to the Trojan War (Iliad 1, 77–79) or resplendent championship belts awarded to prize-fighters since the nineteenth century of our era, these ostentatious displays have as much to do with swagger as they do with protection.

The copper-alloy belts found at Hasanlu demonstrate varying degrees of entanglement with South Caucasian material culture, and thus exemplify the differentiated integration of exogenous traits into, or hybridization of, local material practices at the site. Most of the belts from Hasanlu conform to three distinct styles of decoration: simple South Caucasian-style repoussé dots and lines, rows of hemispherical riveted studs, and a combination of finely incised surface detail with repoussé animals in high relief. Each of these three types is represented in one of the ‘Warrior Burials’, a class of elite Period IVb male burials featuring weapons and armour (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli2016; Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015),Footnote 13 and each appears to correspond to a particular type of citadel context. We turn to the exploration of these belt types, the individuals with whom they are associated, the semantic potential of their architectural contexts, the way they manifest varying degrees of hybridization, and their role in the construction of local identities.

A view from the burials

The Hasanlu ‘Warrior Burials’ in which excavators discovered these belts differ from earlier male burials at the site in their inclusion of quantities of armour and weapons—spear points and swords of copper-alloy, iron and bimetallic construction. They stand out, as well, among contemporary male burials, which contain less elaborate assemblages and fewer weapons (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli2016; Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015). Burial rituals and resulting assemblages, particularly the elements relating to the dress and appearance of the buried individuals, are opportunities for constructing and negotiating the social identity of the deceased (e.g. Arnold & Jeske Reference Arnold and Jeske2014; Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006; Sørensen Reference Sørensen and Nelson2007). The characteristics that distinguish these ‘Warrior Burials’ demonstrate the emergence in this period of the communal construction of a new, elite and distinct social category. ‘Warrior’, however, is only one of several sex-specific social categories that emerged amongst the Period IVb burials, providing evidence for heightened negotiation of social identities and relationships (Cifarelli Reference Cifarelli2016; Reference Cifarelli, Cunningham and Driessen2017a,b). In addition to sheet-metal belts, the presence of swords in burials SK107 & 105–106 is significant. Unlike knives, arrows or spears, swords were developed specifically for battle, used in a style of combat that takes place within an arm's length and requires lengthy training that can visibly modify the physique (Fontijn Reference Fontijn, Pearson and Thorpe2005, 145–7). Each of these male bodies, gleaming in bronze armour and bristling with iron and copper-alloy weapons, performed in death and perhaps in life a specifically masculine, militarized identity. The ‘warrior’ category was not monolithic. The identities of these ‘warriors’, as particularized by the use and modification of metal belts, were inflected, as we shall discuss, with varying types of interactions with the north.

SK107 (Operation LIe Burial 5): a South Caucasian belt

Burial SK107 is that of a mature adult male, with a belt coiled near the head, weapons and personal ornaments in bronze and iron, as well as ceramic vessels, and carnelian and shell beads at the neck (Fig. 4). Stratigraphic and artefactual evidence suggests that SK107 was among the earlier Iron II graves in the Outer Town (c. late eleventh–tenth century bc) (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015, 82, 108; Rubinson Reference Rubinson and Kroll2012a, 396). The repoussé decoration of the belt features three rows of small punched dots framing a rectangular field defined by a repoussé line, which in turn contains a single horizontal line of punched dots (Fig. 5).Footnote 14

Figure 4. Excavation drawing of Burial SK107 (Operation LI, Burial 5) and contents. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 5. Photograph and drawing of belt HAS59-262. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

This object is the earliest attestation at Hasanlu of a South Caucasian belt. It conforms to Manuel Castelluccia's ‘decorated bands’ subtype, characterized by a regular arrangement of repoussé lines and rows of dots.Footnote 15 Common throughout South Caucasia from the twelfth to the eighth century bc (Fig. 6) (Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017, 25–6), examples also appear at Marlik (Negahban Reference Negahban1996, 284) and later in Urartian contexts (Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017, 22; Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015, 105; Rubinson Reference Rubinson and Kroll2012a, 394). The style found in Burial SK107 is so similar in appearance and craftsmanship to examples from the South Caucasus that we believe it to have been created there.

Figure 6. South Caucasian ‘decorated bands’ style belts from Chagoula-Derre, Gantaidi, Samtavro, Leninakan and Tli. (After Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017.)

As an imported object used in a new setting, this belt exemplifies Stockhammer's relational entanglement. Our understanding of it as a manifestation of hybridization is complicated because this mortuary assemblage indicates that the individual in Burial SK107 may himself have been a South Caucasian ‘import’. Particular weapons link him to South Caucasian material culture and mortuary practices, as do dress elements. On his right arm above the elbow, excavators found a simple, heavy, iron penannular armlet (Fig. 4G), nearly identical to that found on the body of an Urartian soldier killed at Hasanlu as he attempted to loot the Gold Bowl and other valuable items from elite residence BBIW (Danti Reference Danti2014; Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015) (Fig. 7).Footnote 16 These armlets are rigid and their interior diameters small, suggesting that that they were placed on the arm in adolescence and ‘grown into’ (Cifarelli in press b). Dress items that cannot be removed are permanent body modifications, and intimately linked to the identity of the wearer (e.g. Derevenski Reference Derevenski2000, 38–9). In this case, the identity that is shared by the man interred in Burial SK107 and the fallen Urartian soldier is likely related to an origin in the South CaucasusFootnote 17.

Figure 7. Excavation drawings of armlets worn by (a) SK107 (HAS59-264); (b) SK493 (HAS64-287); (c) the enemy combatant SK37 (HAS58-468). (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

If this belt were entirely unique at Hasanlu, we could interpret it as a possession of the deceased, and as such, not necessarily integrated into the local material culture. However, fragments of approximately 25 South Caucasian style belts appear in the store-rooms of Period IVb temple BBII, the bulk of which have the same type of simple, embossed geometric decoration seen on the belt from SK107.Footnote 18 Given the direct ties between Hasanlu and the South Caucasus manifest in Burials SK107, in contrast to Assyria, there can be little doubt that to the residents of Hasanlu these objects were recognizably northern. Their introduction to the site and subsequent transformation into votive objects are not necessarily intentional acts of cultural integration. Rather, the repurposing of objects that were quotidian at their point of origin as votives at Hasanlu exemplifies Bakhtin's organic or unconscious hybridization, and demonstrates a shift in meaning. The heightened status accorded to these belts, rendering them suitable for dedication to the gods, could relate generally to their military connotations and their highland origin, or more specifically to their association with an ostentatiously buried individual whose body was marked as an outsider.

SK105-106 Operation LIe Burial 3: a belt in the Hasanlu vernacular

Stratified above Burial SK107, excavators uncovered a stone hypogeum containing two skeletons (SK105 and SK106) (Figs 8a, 8b). Another ‘Warrior Burial’, this grave was disturbed in antiquity, its skeletal remains partially disarticulated. It was nonetheless well equipped, and contained two sheet-metal strips coiled together, one an undecorated strip and the other a decorated belt (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015) (Fig. 9). The burial was also furnished with pottery, beads, an exceptionally worn cylinder seal with copper-alloy caps, copper-alloy and iron anklets, weapons and a number of copper-alloy drinking vessels of types that had served locally as markers of elite status since the Late Bronze Age (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015).

Figure 8a. Excavation drawings of Burial SK105. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 8b. Excavation drawings of Burial SK106. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 9. Drawing and excavation photographs (front and back) of fragments of belt HAS59-232. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

While the copper-alloy vessels link the deceased to established elite drinking practices at the site, others, like the belt (Fig. 9),Footnote 19 point northward, and the short sword is a type associated with South Caucasia and the Talesh (Thornton & Pigott Reference Thornton, Pigott and de Schauensee2011, 159). The rigid, knobbed, iron anklets (Fig. 10a) are a type found in Urartian burials at Iğdyr in the South Caucasus (Barnett Reference Barnett1963, fig. 32), as well as on the body of an Urartian killed at Hasanlu in BBIW (Fig. 10b). The occupant of this tomb participates in the South Caucasian-inflected, militaristic identity of the ‘Warrior Burial’ of SK107, and that of the invaders who destroyed the site.

Figure 10. Knobbed (ball) anklets from (a) Burial SK106 and (b) SK37 (iron), and (c) Igdyr (bronze). (After Reference BarnettBarnett 1963, fig. 32.)

Only one finished end of this belt is preserved. It measures 3 mm thick and 5.5 cm in height, with a total extant length of c. 60 cm. Like the belt in Burial SK107, it is decorated with horizontal rows of dots, but the dots on this belt are created by riveting evenly spaced, small (c. 7 mm diameter) hemispherical copper-alloy studs directly to the sheet-metal. Riveted studs are quite common at Hasanlu, decorating hundreds of objects on the citadel and in burials (e.g. de Schauensee Reference de Schauensee and de Schauensee2011b). Outside Hasanlu these studs are exceptionally rare (Rubinson Reference Rubinson, Fahimi and Alizadeh2012b).

While there are no known examples of belts with riveted decoration within the enormous corpus of South Caucasian and Urartian bronze belts, at Hasanlu excavators found fragments of approximately 30 such belts on the citadel, the majority of which were within the collections of the temple treasuries in BBII (Fig. 11). Made in Hasanlu, with Hasanlu-specific decoration, these belts demonstrate a different sort of entanglement between local and South Caucasian culture. The assemblages and contexts in which studded belts were found—in the temple treasuries among valuable dedications and a wealthy burial surrounded by objects that associate the deceased to both local and northern identity—suggest that belts themselves relate to elite status. The arrangement of studs on metal belts in simple rows was intended to replicate, in the local vernacular, the patterns of repoussé dots on imported South Caucasian belts. The resulting objects represent the conscious and clearly intentional hybridization of local (studded decoration) and non-local (sheet-metal belts) metal-working traditions. The notion of a locally produced imitation of a exogenous form, particularly when the origin of that form lies in the home of a powerful enemy, has traditionally been interpreted through the lens of either passive acculturation or active emulation; i.e. that such belts were produced under the influence of, and in order to imitate, warriors from the north. Such explanations assume a hierarchical relationship between the two contexts, and that the material engagements from which these local products emerge embrace and reify the hegemony of the ‘foreign’ point of origin. We assert, rather, that these local iterations of South Caucasian belts evoke the military power and potential threat of warriors to the north and, by translating these objects into the local material idiom, place that power in the service of local elites. The deliberate juxtaposition of elements inherent to these studded belts offers their makers and owners the shared opportunity to resist and signal resistance of subordination, and to negotiate a distinctly local militarized identity at Hasanlu.

Figure 11. Site plan showing loci of belts on citadel. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

SK493a Operation VIh Burial 3: an elite amalgamation

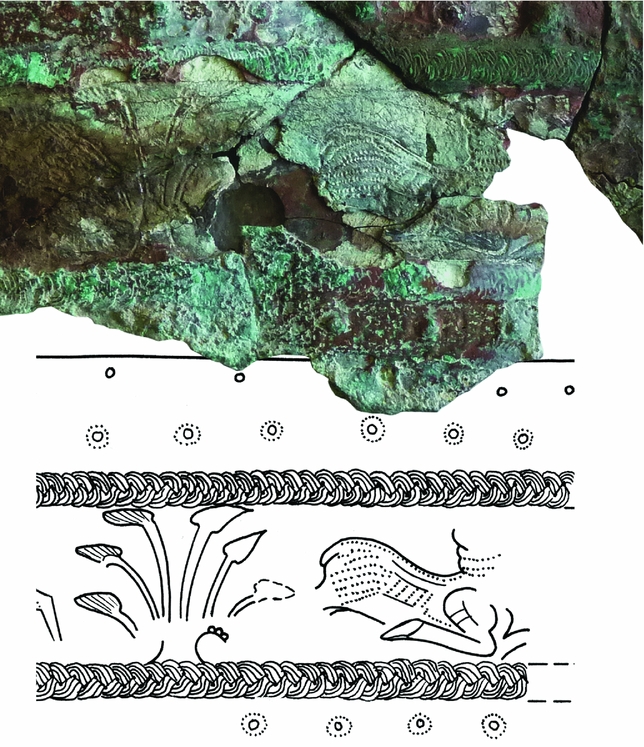

An example of the third Hasanlu belt type was excavated in 1964. Burial SK493a is a simple inhumation of an adult male whose grave goods are arguably the wealthiest among the Period IVb burials (Danti & Cifarelli Reference Danti and Cifarelli2015). It contains high-value objects including copper-alloy and iron weapons, elite metal drinking vessels, personal ornaments (Fig. 12) and an extraordinary incised and repoussé copper-alloy belt (Figs. 13–15) (de Schauensee Reference de Schauensee and Curtis1988, 52, figs. 36–37).Footnote 20 This belt is far more complexly constructed and elaborately decorated than those we have examined thus far. It features a long, horizontal strip with carefully incised figurative and abstract decoration, a large, circular medallion with repoussé animals that have protome heads and chased surface decoration, and a terminal formed by a tapering strip of incised copper-alloy sheet ending with a hook. The form of the belt—particularly the circular medallion and tapering, hooked terminal—is not paralleled within the corpus of South Caucasian or later Urartian belts.Footnote 21 As such, it is a unique, local object.

Figure 12. Excavation drawing of Burial SK493a (Operation VIh, Burial 5) and contents. (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 13. Excavation drawing of belt HAS64-288 (University Museum 65-31-726). (Courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 14. Belt medallion HAS64-288 (University Museum 65-31-726). (Photograph: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 15. Incised detail on HAS64-288, photo and drawing (University Museum 65-31-726). (Photograph and drawing: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

The horizontal strip that forms the body of the belt is incised with intricate double guilloche borders and rows of embossed dots between the guilloche and the edge of the metal strip. Tiny perforations at its edges allow for attachment to leather or fabric. In the central horizontal field is a register of incised palmettes alternating with groups formed by a palmette flanked by kneeling animals (Fig. 15). The same guilloche borders the medallion and is the sole decoration on the tapered terminal of the belt. On the terminal, three horizontal guilloche rows converge toward the hooked end, crossed at intervals by two vertical guilloches.

The bulk of the visual field on the medallion is dominated by two pairs of animals. Their bodies are rendered in low relief, and their heads protrude three-dimensionally from the sheet. Each pair includes a lion at the left extending one or two front legs toward a couchant hooved animal (Figs. 14, 15). Additional incised details on the surface of the medallion are perhaps obscured by corrosion.

Two additional belts of this type were found at Hasanlu in the collapsed first floor of the elite residence BBIW (Figs. 12, 16, 17).Footnote 22 BBIW, located close to the largest temple at the site (BBII) and at the heart of the monumental complex on Hasanlu's citadel, is the largest and most elaborately equipped residence at Hasanlu (e.g. Danti Reference Danti2013a, 19–22). The collection of objects stored on its first floor include the most celebrated finds at the site, the Gold Bowl (and the objects looted with it) and the Silver Beaker (e.g. Danti Reference Danti2014; Winter Reference Winter1989). BBIW—an elite residence with a large audience hall and the most valuable artefacts at the site—is an excellent candidate for a seat of power.

Figure 16. HAS58-450 (University Museum 59-4-113). (Photograph and drawing: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 17. HAS58 244 (University Museum 59-4-158). (Photograph and drawing: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

The chronological and geographical parallels for numerous aspects of the expertly wrought metal belt from Burial SK493a are not difficult to identify. The motif of animals flanking a palm or palmette is widespread in the ancient Near East, and the particular composition of the elements shown on this belt relates most closely to Assyrian and later Urartian examples (e.g. Barnett Reference Barnett1950, pl. viii; Bartl Reference Bartl2014, Tafel 27b; Layard Reference Layard1849, 295–6; Mallowan Reference Mallowan1966, fig. 37; Özğüç Reference Özğüç1966, fig. 14). The outlines of the recumbent animals and palmettes on the belt are incised with a dynamic and fluid linearity that recalls the naturalism of Middle Assyrian ivories, glyptic, and wall painting (Andrae Reference Andrae1923, pls. 2–3; Harper et al. Reference Harper, Klengel-Brandt, Aruz and Benzel1995, cat. nos. 45, 46, 51). However, the articulation of the internal contours and surfaces of the animal bodies using rows of tiny dots and hatch marks is more characteristic of decoration on artefacts found at Iranian sites such as Marlik (Negahban Reference Negahban1996, col. pls. XIII–XV), as well as representations of animals on belts in the South Caucasus (e.g. Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017, figs. 64–66).

The beautifully incised double guilloche that borders the belt is another visual element broadly distributed through the ancient Near East and eastern Mediterranean in the Bronze and early Iron Ages. It appears frequently on belts from South Caucasian sites, both by itself and bordering figurative and geometric decoration (Castelluccia Reference Castelluccia2017, 27–8). It borders the luxury metalwork from the cemetery at Marlik (Negahban Reference Negahban1996, col. pls. XI–XIII). Similarly, the concurrence on the medallion of several different metal-working techniques—repoussé high and low relief and incised lines and dots—is well attested in the precious metal vessels found in the cemetery at Marlik (Negahban Reference Negahban1996, col. pls. XI–XIII). Finally, the scene of lions juxtaposed with prey animals on the medallion exemplifies an iconographic motif not attested to in northern Iranian or South Caucasian imagery, but well known from the Syro-Mesopotamian and Elamite worlds (Root Reference Root and Collins2002, 202–3).

This belt shows the integration of a South Caucasian artefact type into Hasanlu's material culture, produced with a highly innovative combination of iconographic elements, decorative strategies and technologies which are traceable to points far from Hasanlu in Syro-Mesopotamia, the Caucasus and Iran. Although the ultimate origins of these characteristics are far flung, they share an important feature—they are well represented among the ‘foreign’ and heirloom objects collected and enclaved within the treasuries and storerooms of Hasanlu itself. These rooms were filled with thousands of luxury objects and curiosities, imported and locally made. The presence among these objects of inscribed and otherwise datable examples provides clear evidence that local elites had amassed and safeguarded this collection over generations (Cifarelli in press c).Footnote 23

Within these collections, for example, fragments (found in temple BBII) of incised, Assyrian-style ivory panels show fluidly drawn, lifelike renderings of recumbent animals flanking palm trees, in postures identical to those on the belt (Muscarella Reference Muscarella1980, 156–7, no. 290) (Fig. 18).Footnote 24 Features including naturalistically depicted animals and palm fronds with bulbous terminals appear on cylinder seals from BBII (Marcus Reference Marcus1996, nos. 78, 79) (Fig. 19). The guilloche that borders the belt appears as a design element on a number of objects from the site, including on the aforementioned Gold Bowl (Winter Reference Winter1989, 90) (Fig. 20), as well as in a simpler, less organic form on a number of the ivories found in the destruction of the Period IVb citadel (Fig. 21) (e.g. Muscarella Reference Muscarella1980, figs. 21–22, 40, 55a, 57). The dotted and hatched articulation of the surfaces and contours of the animals on the belt are present on the Hasanlu Gold Bowl as well.

Figure 18. Assyrian-style ivory HAS64-722 (University Museum 65-31-342). (Photograph: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 19. Cylinder and impression, ‘Middle Assyrian Stylistic Legacy’ HAS60-1027 (University Museum 61-4-21). (Photographs: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 20. Hasanlu Gold Bowl and detail, HAS58-469 (Tehran Museum 10712). (Photographs: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

Figure 21. Hasanlu Local-style ivory HAS70-409 (University Museum 71-23-165). (Photograph: courtesy of the Penn Museum.)

In sum, most ‘foreign’ elements of the belt buried with SK493a can be found within the eclectic collections in the temples and elite residences at Hasanlu itself. And as was the case for the hybridized South Caucasian belts found in the treasuries of BBII, the collected objects themselves have been subject to processes of hybridization. In the context of these important collections, exotics, heirlooms and locally made objects acquire new meanings replete with communal identity, memory and relationships, even as their varied origins are invoked.

While the art-historical and archaeological impulse, when confronted with ‘foreign intrusions’ into a mixed material culture, is to situate them within their communities of origin, we argue that these traits were not necessarily viewed in relation to distant and disparate points, even if we presume that Hasanlu residents were fully aware of them. Rather than demonstrating that artistic production at Hasanlu deliberately emulated purportedly more sophisticated Mesopotamian or Iranian artistic traditions, the eclecticism of the objects produced there can be explained through more emic, micro-contextual processes. We assert that elements that appear ‘foreign’ to a contemporary scholar were understood at Hasanlu as relating to significant, high-status local collections, the curation of which was an essential to the construction of communal identity. As material entanglements, these belts are more complex and nuanced than the utilitarian studded belts. Drawing upon the site's most precious and carefully guarded heritage, these belts intentionally produce a new and courtly visual discourse. The evident multivocality of these objects is deceptive, in a way, because these varied voices speak on behalf of the community of Hasanlu. Moreover, the presence of these belts in the most elite contexts at the site suggests that they operate within a particular network of relationships. Linked physically with local power structures at the site, their heteroglot nature is a means of asserting local identity and power to the residents of Hasanlu in the face of the Urartian threat. These belts participate in the ‘official’ discourse of resistance to Urartian annexation, simultaneously acknowledging the shared cultural milieu within which Urartu and Hasanlu operated, and asserting an independent, sophisticated, Hasanlu-specific identity that is not subordinate to Urartu.

Conclusion

These belts demonstrate the complexity of the relational and material entanglements at Hasanlu, the varying roles of heteroglot objects there, and the ways in which hybridization can express and negotiate power imbalances. South Caucasian-style belts appear to have been introduced early in Period IVb (c. 1050–800 bc), perhaps initially as the personal property of a migrant or migrants from the north. Their presence in temple treasuries demonstrates their transformation by the local population from ‘foreign’ but quotidian objects marking the bodies of potentially dangerous strangers to high-status items that contributed to the increasingly militarized identity of the elite in the community. Emerging slightly later, a permutation of this type of object crafted in the local metalworking vernacular, the studded belt, manifests a more conscious and intensive material interaction between Hasanlu and its northern neighbours. As relatively straightforward, utilitarian appropriations of the South Caucasian sheet-metal belt type, studded belts appear in contexts identical to those of South Caucasian ‘originals’—an elite male burial and temple treasuries. Their creation and use are not acts performed in simple, ineluctable emulation of northern military might. Studded belts manifest local agency at Hasanlu, the conscious choice to grapple with and incorporate aspects of the material culture of a threatening neighbour, at the same time neutralizing the external menace with an overlay of a familiar material argot. These heteroglot forms themselves defy the encroachment of the kingdom of Urartu, and their participation in an elite, militarized identity signals the social integration and even elevation of that defiance.

Finally, the rich decoration of the exceptionally wrought belts found in elite contexts of Burial SK493a and BBIW mines the visual lexicon of communal memory, identity and power embodied in the assemblage of treasures—local and imported, innovative and heirloom, familiar and exotic—collected in the temple repositories and displayed in elite residences. Rather than a simple borrowing of the splendour of distant lands, these belts speak in the rich, varied and ancient language of the heritage of Hasanlu itself, offering a non-cooperative utterance in defiance of potential annexation by the Urartian kingdom. This ‘courtly’ fusion of elegant attributes of the community's most precious possessions was, it seems, restricted to loci of temporal power at the site and appears as a resolute assertion of the autonomy and sovereignty of the local community and their elites.

Local artisans and patrons engaged in their own visual and material alchemy in the creation and use of these powerful belts. At Hasanlu, local agents consciously and expertly mixed and manipulated the elements of visual and material culture that were available to them, crafting complex and sophisticated objects in which present and past, near and far, familiar and threatening, are wrought together in the service of the elite at the site. As heteroglot expressions, these belts were used and produced in dialogue with South Caucasian, early Urartian material culture, in a time of increasing interaction with and threat of Urartian hegemony. Through these acts of intentional, conscious hybridization, the belt—a utilitarian emblem of South Caucasian and later Urartian militarism—is put to the task of constructing a specifically local, elite, temporal power at Hasanlu, surely an act of resistance to the very forces that threatened, and ultimately brought to an end, life at Hasanlu.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Michael Danti (ASOR) and Richard Zettler (University of Pennsylvania) for access to the Hasanlu Excavation archives and the materials in the University Museum, and for permission to publish these items, and Katherine Blanchard, Keeper of the Near East Section, for graciously facilitating our work. Authors Castelluccia and Dan are grateful to Prof. Adriano V. Rossi, President of ISMEO (International Association of Mediterranean Studies) for research support. Many people provided feedback on drafts of this paper, including Isabel Cifarelli, Amy Gansell, Stephanie Langin-Hooper, Karen Rubinson, Paul Sanchez, Priscilla Vitolo, Chiara Zecchi, and the three anonymous reviewers. We thank them for their wise counsel, and any mistakes remain our own.