CLINICIANS CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

It is unknown what crucial wellness activities and policies currently exists in Canadian academic emergency medicine programs.

What did this study ask?

What is the current state of wellness activities and policies in Canadian academic emergency medicine programs?

What did this study find?

This review found important work across the domains of formal wellness programs, scheduling, wellness measures, career transitions, and financial considerations.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Highlighting local strengths and weaknesses, this environmental scan can aid programs in determining areas to focus efforts.

INTRODUCTION

Fostering a culture of wellness in emergency medicine (EM) is a critical component to the delivery of high-quality clinical care. Wellness is an important protective factor that reduces physician burnout. In EM, where rates of burnout rank among the highest of all medical specialties, this is sorely needed.1–Reference Shanafelt, West and Sinsky3

Burnout is indiscriminate, impacting staff physicians, residents, medical students, patients, and hospitals.Reference Taher, Crawford, Koczerginski and Argintaru4–6 Specifically, burnout is associated with increased rates of depression, substance use, and suicidal ideation among physicians and residents.Reference Taher, Crawford, Koczerginski and Argintaru4,Reference Wallace, Lemaire and Ghali7–Reference Atkinson, Ducharme and Campbell9 Doctors and residents with burnout have higher rates of errorReference Taher, Crawford, Koczerginski and Argintaru4,6–Reference Patel, Sekhri, Bhimanadham, Imran and Hossain8,Reference Patel, Bachu, Adikey, Malik and Shah10 and lower patient satisfaction.6 Burnout and stress also impact the ability to perform challenging procedures.6 Finally, burnout increases physician turnover and absenteeism, lowers productivity, and increases desire to leave practice.6–Reference Patel, Sekhri, Bhimanadham, Imran and Hossain8,Reference Lee, Stewart and Brown11 At hospital and systems levels, these factors have important implications on the overall functioning of the workforce. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that both individual-focused and structural/organizational strategies can result in clinically meaningful reductions in burnout among physicians.Reference West, Dyrbye, Erwin and Shanafelt12

The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) Wellness Committee was formed in 2018 to advocate and promote personal and professional wellbeing in EM across Canada. In keeping with the Section mission surrounding physician and resident wellness, an environmental scan survey was conducted to establish a greater understanding of wellness activities and policies in Canadian academic EM programs. Academic sites were chosen as the initial area of focus as a proxy for broader functioning and for the impact these programs have upon the wellness of future physicians. Highlighting local strengths and weaknesses, this environmental scan serves as a pulse check on the status of wellness activities in academic EM departments across Canada. In addition, this scan forms the foundation for planning future wellness initiatives to address gaps in wellness programming nationally.

METHODS

An 89-question questionnaire was developed with a focus on the following themes related to wellness in EM: formal wellness programs and leadership opportunities, shift scheduling, daily and long-term wellness measures, career transitions, and financial considerations (online Supplemental Appendix). The development and design of survey questions was based on consensus among wellness leads. The questionnaire used a combination of questions including yes/no and numerical responses as well as areas to provide free-text clarification. The questionnaire was reviewed and pilot tested among members of the CAEP Wellness Committee Executive, and revised for clarity. The final questionnaire was distributed by means of email to designated department/division heads and/or clinician wellness leads (or equivalent program directors) across 17 academic programs in Canada. Nonresponding programs were contacted by the lead author (R.L.) per ethics protocol to confirm correct contact information, and to discuss/confirm the most appropriate individual to provide information if open to participation. The lead author (R.L.) contacted each individual site as required to review data with each wellness lead (or equivalent) in a series of telephone discussions where discrepancies existed, to ensure all questions were clearly answered. A variable response could be recorded by the responder. In academic centers where the survey was distributed to multiple hospitals due to size of program, answers that were discrepant (i.e., three hospitals said yes, two said no) a variable response was selected for the overall academic center. Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel® 2011 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) spreadsheet for analysis. Descriptive statistics including proportions, means, medians, and ranges were calculated. Data collection was complete.

RESULTS

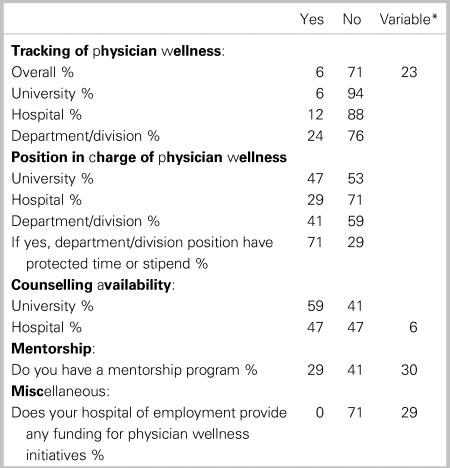

While formal wellness programs may exist in varying degrees across the 17 universities, most initiatives were found to exist only at local divisional or departmental levels. Only 37% of programs currently track physician wellness in any manner, primarily at the division level. Only 12% of all programs track wellness regularly and in a formal manner. There is a broad variability of established leadership positions that have been reserved for Physician wellness, existing across many levels (Table 1). Please note, academic programs were said to be variable in a selection if either some but not all hospitals within an academic center had a program, or within a hospital, some but not all consultants had a benefit based on their academic status.

Table 1. Environmental survey responses regarding formal programs/leadership (N = 17)

* Variable = either some but not all hospitals within an academic center had program, or within a hospital some but not all consultants had benefit based on academic status.

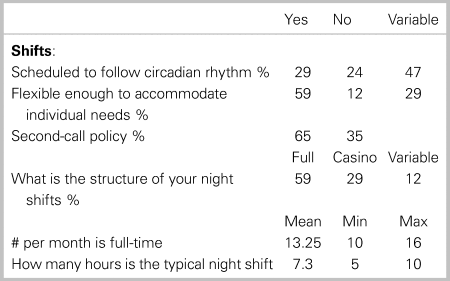

Shift work in EM affects provider well-being as it disrupts circadian rhythms.Reference Frank and Ovens13 Shift characteristics were found to vary tremendously across the 17 academic institutions. While most programs tried to account for circadian rhythms in shift scheduling, 7 of 17 (41%) did not do so. Despite this, there were many initiatives that appeared to meet not only the individual needs of doctors, but tried various techniques, such as casino shifting, and varying shift lengths (Table 2).

Table 2. Environmental survey responses regarding Shift Characteristics (N = 17)

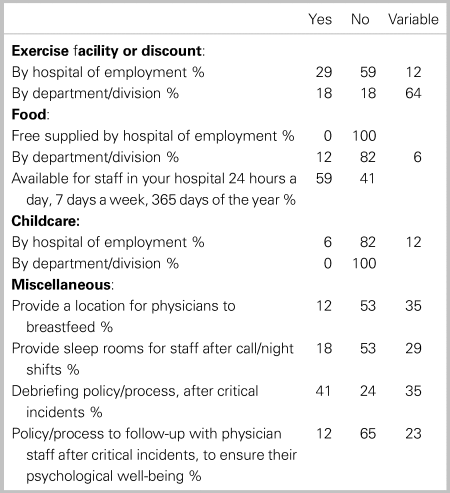

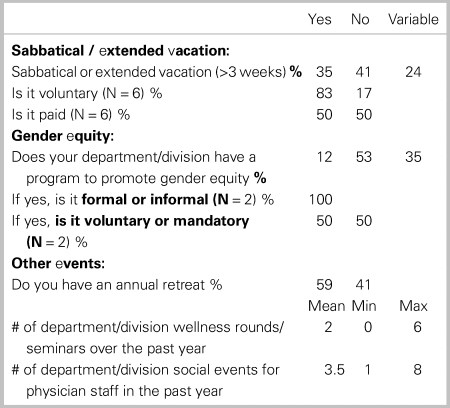

In terms of specific factors and programming related to the promotion of daily wellness, areas that had the greatest consistency of availability were food (59%), and any form of debriefing process after critical incidents (41%) Access to childcare, sleep rooms, and formal policies to follow-up with staff following critical incidents was found to be the most limited (Table 3). In regard to long-term wellness initiatives, 10 of 17 (59%) provide some form of sabbatical or extended vacation program, of which the majority are voluntary. Roughly 50% of departments reported having some form of gender equity program, and annual retreats (Table 4). Transitions are known to cause some the greatest periods of stress for physicians during their career.

Table 3. Environmental survey responses regarding programs for daily wellness (N = 17)

Table 4. Environmental survey responses regarding programs for long-term wellness (N = 17)

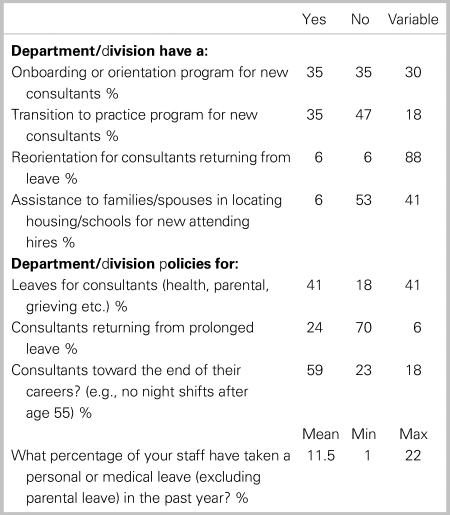

In regard to easing transitions, many programs have developed programs for the initiation of leaves (82%), or onboarding (64%). There is a significant amount of reorientation programming for clinicians returning from leave (94%) but almost all cite variable development of these programs (Table 5).

Table 5. Environmental survey responses regarding programs for easing transition (N = 17)

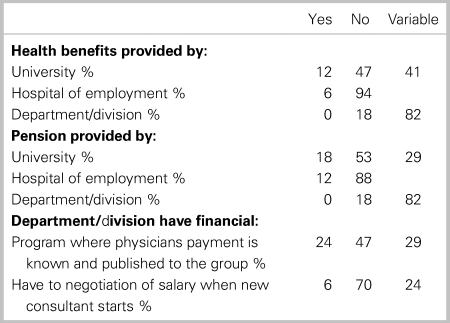

In regard to financial programs, many divisions cite variable support of health benefits (76%) and pensions (76%), with several depending on type of appointment and relationship to the university. There are some programs (53%) showing fiscal transparency (Table 6).

Table 6. Environmental survey responses regarding financial setup / benefits (N = 17)

DISCUSSION

This report is the first comprehensive review of wellness activities and programs within Canadian academic EM centers. Significant activity was found across all of the evaluated domains, including formal wellness programs and leadership opportunities, shift scheduling, daily and long-term wellness measures, career transitions, and financial considerations. The most striking finding was the variability and inconsistency of wellness program availability between and within centers. This likely reflects the nature of the rapidly evolving landscape of wellness in EM. The specific example of low numbers of breastfeeding spaces and policies for returns after leaves is particularly concerning. This report would suggest that a comprehensive survey within divisions/departments may lead to some opportunities to declare a set of minimum standards for programs to decrease variability between sites or academic versus clinical appointment.

We note three tangible positive findings that were evident from the survey. First, counselling was available at the university or hospital level in a large percentage of academic sites. This is critically important given recent research showing a large bias against seeking help among doctors surveyed by the Canadian Medical Association.Reference Simon and McFadden14 Furthermore, the College of Family Physicians and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada's accreditation standards mandate that academic EM residency programs establish and maintain means for resident physicians to access counselling services for support with stress, burnout, or crisis.Reference Taher, Hart and Dattani15–17 Despite this positive finding, there remains room for improvement as four academic centers did not have either hospital or university level support. Second, 77% of academic sites have some degree of departmental policies for physicians at the end of their careers. Given the large reliance on shift work, and the difficulties with adaptation to disruptions of circadian rhythm with aging, the progressive policies that most academic centers have adapted is encouraging. This is important as overall dissatisfaction has been shown to be a significant factor underlying intention to quit and early retirement.Reference Cydulka and Korte18–Reference Likourezos, Chalfin, Murphy, Sommer, Darcy and Davidson20 Likourezos et al. reported that emergency physicians who were dissatisfied with professional autonomy were more likely to seek a new position or exit the profession.Reference Likourezos, Chalfin, Murphy, Sommer, Darcy and Davidson20 Third, almost 60% of centers were found to hold an annual retreat. Although not much literature is available on the effect of retreats on wellness, they do provide a departmental/divisional forum for reflection and future goal setting, which is intrinsically tied to professional fulfillment and wellness.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement introduced the Triple Aim in 2008 as a framework that describes an approach to optimizing health system performance through: (1) improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction); (2) improving the health of populations; and (3) reducing the per capita cost of health care.Reference Berwick, Nolan and Whittington21 Currently, many institutes now pursue the “quadruple aim” in 2014 with institutions advocating for health care team wellness as a crucial fourth aim.Reference Bodenheimer and Sinsky22 Our survey suggests that, if this fourth aim is included in the framework, there is currently a significant gap in top-down support/structures. In fact, it is difficult to even measure the metric of wellness. In our survey, most wellness programs were at the division/department level, not at the hospital or university level. It appears we have a long way to go before the quadruple aim can become a meaningful reality.

Our study had a 100% response rate, indicating a comprehensive assessment of Canadian academic EM programs has been achieved. The survey assessed a broad range of infrastructure consistent with career sustainability and wellness. As in prior academic scans in EM, the data obtained from this survey can be the springboard to encourage further initiatives.

There are several limitations to our study. Many wellness issues are managed at the hospital level, e.g., shifts. Due to the surveys being carried out at the medical schools and not the 60+ academic hospitals in Canada, we do not have a complete picture. The survey was based on the report of local physician champions, who are likely to be the most aware of programming and, thus, may not reflect the general awareness of all departmental/division members. In addition, wellness initiatives may stem from university, hospital, or departmental/divisional programs, and particularly so in programs with multiple sites (e.g., British Columbia). Although we delineated the source of programming, the responses best reflect the wellness champions’ local situation, and it is possible that other hospitals or groups had differing initiatives that were not included here. Although we attempted to examine gender equity, this survey was not designed to examine diversity issues in general, which would be an opportunity for future research. Finally, we did not ask about the status of the local electronic medical record (EMR) system and supports for physicians in this regard.Reference Melnick, Dyrbye and Sinsky23

EM programs can use the results of this study as a framework to examine what systems are currently in place, determine their relative weaknesses and strengths, and set goals and priorities for development. National collaboration between EM programs to develop more comprehensive wellness programs may speed our specialty toward the Quadruple Aim goal. Our results may aid in discussions with hospitals, universities, and stakeholders to help gain support for these initiatives. The authors believe that the high priority areas for wellness initiatives are as follows: the development of a structured practice of critical incident debriefing; the provision of places to either sleep surrounding night shifts and/or spaces to breastfeed on shift; and the creation of programs to assist physicians with transitions, such as onboarding or returning to work following leave.

CONCLUSION

This research provides a comprehensive review of wellness programs at academic EM sites across Canada. We highlight important work across the domains of formal wellness programs and leadership opportunities, shift scheduling, daily and long-term wellness measures, career transitions, and financial considerations. Highlighting local strengths and weaknesses, individual centers can review where they stand in comparison to survey findings, and plan and advocate for future growth of wellness programs. This may also form the foundation for establishing future wellness initiatives to address gaps in wellness programming nationally.

Supplemental material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.408.

Acknowledgments

We particularly thank Shanna Scarrow from CAEP for logistical support. In addition, we are very grateful for the cooperation of emergency medicine leaders from each university: British Columbia (Jim Christenson), Alberta (Bill Sevcik), Calgary (Eddy Lang), Saskatchewan (James Stempian, Alison Turnquest), Manitoba (Alecs Chochinov), Northern Ontario (Gary Bota,), Western (Adam Dukelow), McMaster (M. Welsford), Toronto (Anil Chopra), Queens (David Messenger), Ottawa (Guy Hebert), McGill (Marc Afilalo, Sara Ahronheim), Montreal (Nathalie Cairefon), Laval (Xavier Huppe), Sherbrooke (Eric Lachance, Martin Basaillon), Dalhousie (David Petrie, Laurel Murphy), and Memorial (Michael Parsons).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.