CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

There is variation among emergency department (ED) physician analgesic regimens for patients discharged with acute musculoskeletal fractures.

What did this study ask?

What proportion of patients presenting to the ED with acute fractures were discharged with an opioid prescription?

What did this study find?

This study found that just under one-third of patients were discharged with an opioid prescription, with variation in ranges prescribed.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

We recommend the standardization of ED opioid prescriptions to help with combatting the current opioid epidemic.

INTRODUCTION

Rates of opioid prescriptions have been increasing globally, with Canada having the second-highest rate.Reference Fischer, Jones and Rehm1 In the last decade, there has been a fourfold increase in opioid prescriptions and a twofold increase in opioid-related mortality.Reference Gomes, Mamdani, Paterson, Dhalia and Juurlink2 The majority of overdoses occur amongst the young population that has resulted in a threefold increase in years of life lost.Reference Gomes, Mamdani and Dhalla3 Furthermore, elderly patients present a challenge, as studies have shown increased rates of falls, fractures, and mortality.Reference Makris, Abrams, Gurland and Reid4

Acute musculoskeletal pain is a common presentation seen in the emergency department (ED). Finding an appropriate analgesic regimen is challenging, and there is often variation amongst ED physicians, even those within the same ED.Reference Barnett, Olenski and Jena5-Reference Hoppe, McStay, Sun and Capp7 Furthermore, studies have shown a positive correlation between ED opioid prescriptions and risk of long-term use.Reference Barnett, Olenski and Jena5,Reference Hoppe, Kim and Heard6,Reference Jeffery, Hooten and Hess8-Reference Butler, Ancona and Beauchamp10 Given the variability in prescription practices and adverse long-term effects, there has been a shift toward creating opioid prescription guidelines. Several studies have suggested that guidelines may be an effective tool to help standardize prescription practices.Reference Chacko, Greenstein, Ardolic and Berwald11-Reference Beaudoin, Janicki, Zhai and Choo13 However, there are currently no validated guidelines for acute musculoskeletal pain secondary to fractures, and variation continues to exist.

The objective of this study was to evaluate ED physician opioid prescription practices for patients presenting with acute fractures. We sought to investigate this by looking at the quantity and type of opioids prescribed for patients discharged from the ED with an acute fracture.

METHODS

Design

We performed a health records review. Starting from January 2016, we included a consecutive sample of 260 patients based on feasibility who were discharged from the ED with acute fractures and received an opioid prescription.

Setting

Health records were obtained from two EDs of a large tertiary care hospital with a combined annual patient volume of approximately 160,000. This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Population

Eligible participants were patients 18 years or older who had a diagnosis of an acute musculoskeletal fracture and were seen and discharged by an ED physician. Patients with fractures above the level of C7, admitted to hospital, and/or discharged by another service were excluded.

Data collection

Medications that contained morphine, codeine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and/or tramadol were included as opioids. In conjunction with The Ottawa Hospital Data Warehouse, a health records database was utilized to screen for fractures based on ICD-10 discharge diagnosis by the emergency physician. First, we screened for all pathologies involving the musculoskeletal system. Then, we only included cases with the term “fractures” and excluded cases that were admitted to the hospital. This generated a list of patients starting from January 2016 and included fractures of rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine; lumbar spine and pelvis; shoulder and upper arm; forearm; wrist and hand; femur; lower leg including ankle; foot excluding ankle; multiple body regions; and lower limb level unspecified (Appendix 1). We then searched for each patient's ED visit. We performed a chart review to collect data on patient demographics, triage assessments (CTAS score, pain score, and pain directive utilization), discharge diagnosis, past medical history, current pain medications, medications given during ED stay, medications given upon discharge, and a pain-related visit to ED one month after discharge (Appendix 2). Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) scores were recorded from 1 to 5, in which 1 represented the highest acuity, and 5 represented the lowest acuity. Pain scores were obtained from the nursing triage notes and were recorded from 0 to 10, in which 0 represented no pain and 10 represented severe pain. Data from pain directive utilization were obtained from a review of nursing notes. The pain directive is utilized by triage nurses when, based on their assessment, a patient required analgesia before assessment by an ED physician. Medications included in the directive were acetaminophen, naproxen, ibuprofen, and tramadol. Opioid prescriptions were analyzed, looking both at standard doses given and morphine equivalents, if applicable. These data were gathered upon review of the ED treatment record. The primary outcome was the amount and type of opioid prescribed upon discharge.

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses with SAS, version 9.4. We present continuous data as mean values with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate, and categorical data as frequencies with proportions. We compared patients who received an opioid prescription with those who did not. To determine between-group differences, we utilized Student's t-test (parametric values), Mann-Whitney test (non-parametric values), and χ2 (for categorical values). We then performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis and presented adjusted odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables with substantial missingness (pain score) and those that had fewer than five expected events (oxycodone use in ED, codeine use in ED) were excluded from the multivariable logistic regression analysis. A total of 803 patients were included in the multivariable analysis. CTAS scores were compared relative to CTAS 5, and fractures were compared with wrist and hand in the analysis as it was the most frequent fracture in this study. We used variance inflation factors with a cut-off of >2.5 to identify variables to rule out multicollinearity before analysis. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

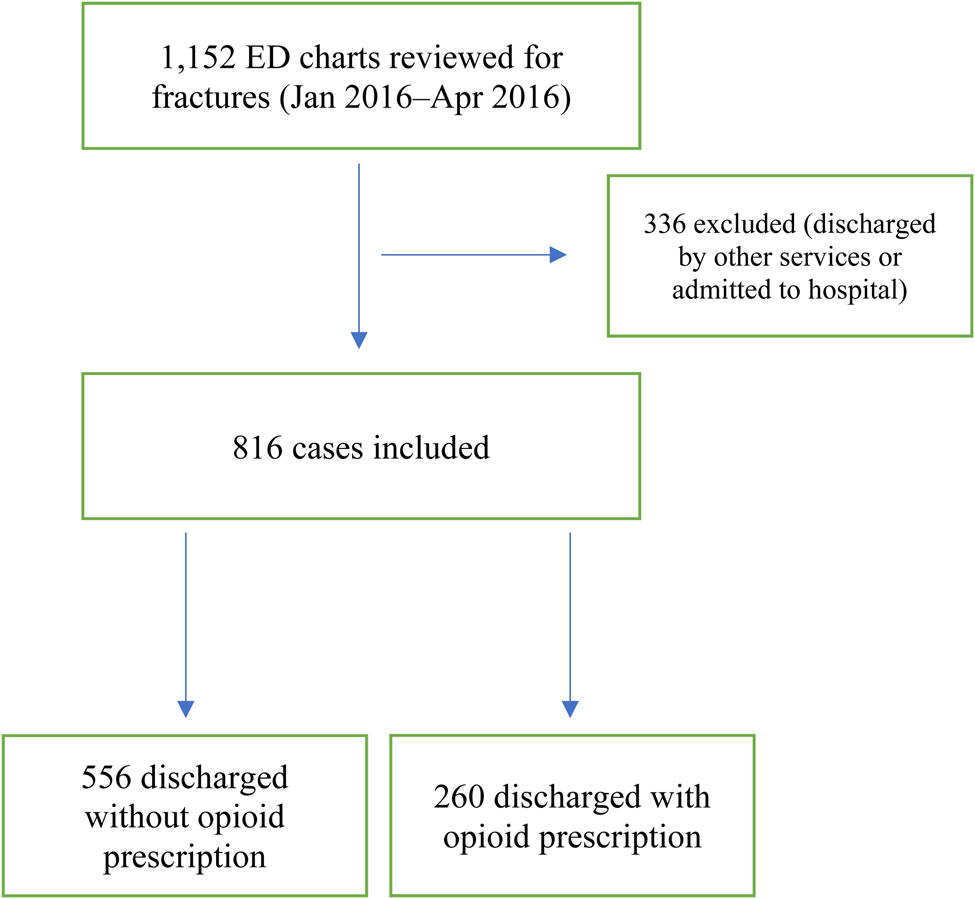

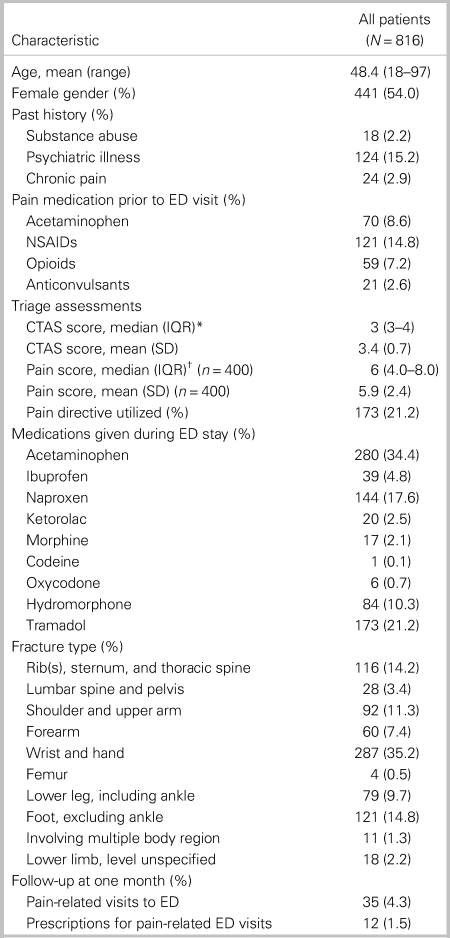

We reviewed 1,152 ED charts from January 1, 2016, to April 30, 2016. Overall, 336 cases were excluded, and 816 cases were included (Figure 1). The mean age was 48.4 years (range 18–97), and 54.0% of the patients were female. A past medical history of psychiatric illness (15.2%), chronic pain (2.9%), and substance abuse (2.2%) was seen in this set of patients. Overall, 7.2% of the patients were using an opioid prior to their ED visit (Table 1). The median CTAS score was 3 (IQR 3.0–4.0). The median pain score was 6 (IQR 4.0–8.0); however, only 51.3% of the patients had a documented pain score at triage. A pain directive was initiated at triage for 21.2% of the patients. The most common medications given during their ED visits were acetaminophen (34.4%), tramadol (21.2%), naproxen (17.6%), and hydromorphone (10.3%). The most common fracture types were the wrist and hand (35.2%); foot excluding ankle (14.8%); and rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine (14.2%). Overall, 4.3% of the patients returned to the ED for a pain-related visit, with 1.5% receiving an opioid prescription upon discharge for that visit.

Figure 1. Flow diagram.

Table 1. Patient characteristics

CTAS = Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ED = emergency department; IQR = interquartile range; NSAIDS = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD = standard deviation.

* CTAS score 1–5 (1 = highest acuity, 5 = lowest acuity)

† Pain score 0–10 (0 = least severe, 10 = most severe)

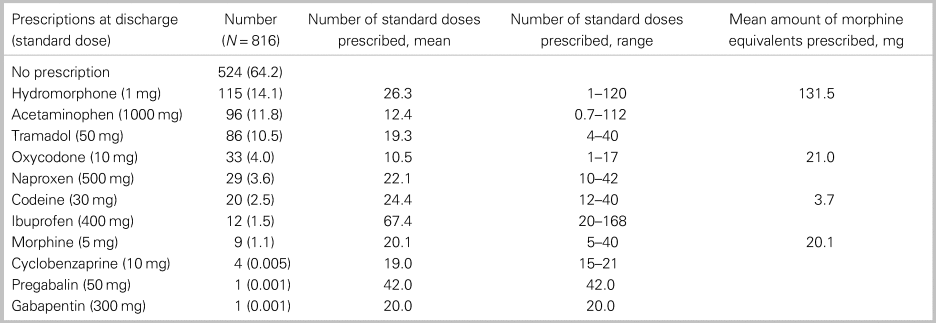

Prescriptions upon discharge are depicted in Table 2. The majority of patients (64.2%) did not receive a prescription upon discharge. Of the 260 patients (31.8%) who were prescribed opioids, hydromorphone was the most common, with 115 (14.1%) patients receiving a prescription. The mean standard dose of hydromorphone (1 mg) was 26.3 (range 1–120). One patient received 120 standard doses of hydromorphone (40 standard doses with two refills). The next most commonly prescribed opioid was tramadol (10.5%), with a mean standard dose (50 mg) of 19.3 (range 4–40). Two patients (0.002%) received neuropathic medications (pregabalin, gabapentin), and four patients (0.005%) received muscle relaxants upon discharge.

Table 2. Prescriptions upon discharge

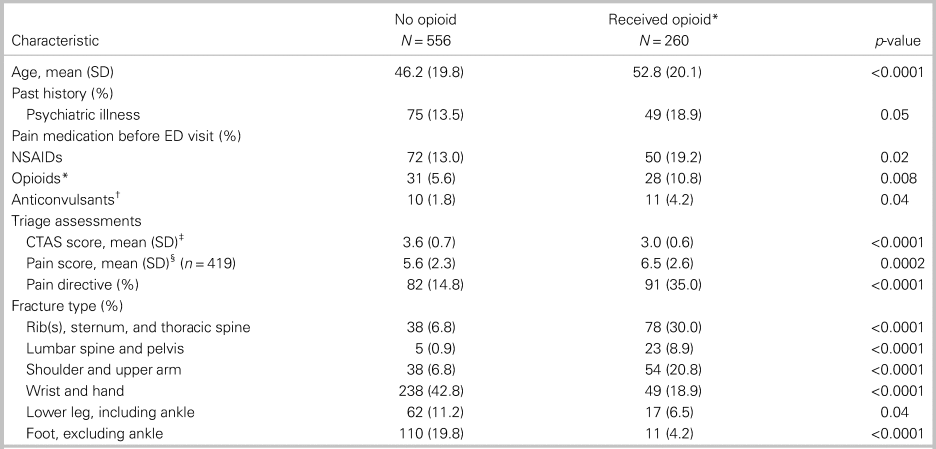

Table 3 presents a comparison of patients who received opioids versus those who did not. As for were associated with opioids being prescribed versus not being prescribed, patients of older age (52.8 v. 46.2 years, respectively; p < 0.0001), history of psychiatric illness (18.9% v. 13.5%, respectively; p = 0.05), history of opioid use (10.8% v. 5.6%, respectively; p = 0.008), lower CTAS score (0.6 v. 0.7, respectively; p < 0.0001), higher pain score (6.5 v. 5.6, respectively; p = 0.0002), and pain directive utilized at triage (35.0% v. 14.8%, respectively; p < 0.0001). Patients with fractures of rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine (30.0% v. 6.8%, respectively; p < 0.0001), lumbar spine and pelvis (8.9% v. 0.9%, respectively; p < 0.0001), and shoulder and upper arm (20.8% v. 6.8%, respectively; p < 0.0001) had a positive association with opioids being prescribed versus not being prescribed. Patients with fractures of the wrist and hand (42.8% v. 18.9%, respectively; p < 0.0001), lower leg including ankle (11.2% v. 6.5%, respectively; p = 0.04), and foot excluding ankle (19.8% v. 4.2%, respectively; p < 0.0001) were associated with opioids not being prescribed versus being prescribed.

Table 3. Significant univariate correlates of opioids prescribed at discharge

CTAS = Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ED = emergency department; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

* Opioids included hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, and codeine

† Anticonvulsants included: pregabalin, gabapentin

‡ CTAS score 1–5 (1 = highest acuity, 5 = lowest acuity)

§ Pain score 0–10 (0 = least severe, 10 = most severe)

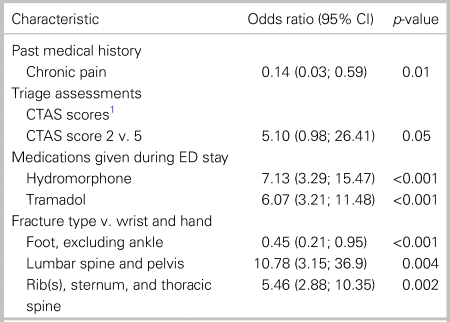

Table 4 depicts a multivariable analysis of 803 patients. Patients with hydromorphone (OR 7.13 [95% CI 3.29–15.47], p < 0.001), and tramadol (OR 6.07 [95% CI 3.21–11.48], p < 0.001) given during an ED stay were more likely to receive an opioid prescription upon discharge. Patients with lower CTAS scores had a significantly higher likelihood of opioids being prescribed, with the highest odds for CTAS 2 (OR 5.10 [95% CI 0.98–26.41, p = 0.05]). Fractures of the lumbar spine and pelvis (OR 10.78 [95% CI 3.15–36.90], p = 0.004) and rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine (OR 5.46 [95% CI 2.88–10.35], P = 0.002) also had a significantly higher likelihood of opioid prescriptions upon discharge. Fractures of the foot, excluding ankle (OR 0.45 [95% CI 0.21–0.95], p < 0.001) and a history of chronic pain (OR 0.14 [95% CI 0.03–0.59], p = 0.01), had a significantly lower likelihood of opioids being prescribed upon discharge.

Table 4. Significant multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with patient's prescribed opioids at discharge (N = 803)

CTAS = Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ED = emergency department; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

*CTAS score 1–5 (1 = highest acuity, 5 = lowest acuity); scores compared with CTAS 5

DISCUSSION

Interpretation

We sought to evaluate opioid prescription practices amongst ED physicians for patients discharged with acute musculoskeletal fractures. Overall, we found that only 260 (31.8%) patients received an opioid prescription. Hydromorphone was the most commonly prescribed opioid, with a wide range of standard doses prescribed. There was one patient who received a total of 120 standard doses of hydromorphone; however, this was a patient on chronic hydromorphone prior to the ED visit and had received two refills. There were no other prescriptions written with refills in this dataset. Interestingly, tramadol was the second most commonly prescribed opioid. Tramadol is included in our ED pain directive, and the high proportion of tramadol prescriptions may be a result of a patient receiving tramadol in the ED and subsequently discharged home with that same analgesic regimen. Despite the minority of patients receiving opioids, there were only 35 (4.3%) pain-related return visits to the ED in one month. Amongst those who returned for a pain-related visit, few received an opioid when discharged from that visit. Overall, few patients received muscle relaxants and neuropathic medications, which have limited evidence for use in the ED for acute fractures.Reference Friedman, Irizarry and Solorzano14 We also found that patients with a CTAS score of 2 had an OR of 5.10 for being prescribed an opioid upon discharge compared with patients with a CTAS score of 5. The lower CTAS scores may correlate with a higher likelihood of a painful fracture for which patients may benefit from a stronger analgesic regimen when discharged. A higher pain score was associated with opioids being prescribed in our bivariate analysis. However, only 51.3% of the patients had their pain score documented at triage, and, thus, the variable was not included in the multivariable model due to missingness. Furthermore, our multivariable analysis showed that the use of hydromorphone and tramadol in the ED significantly increased the likelihood of an opioid prescription upon discharge. It is likely that if these patients required opioids for analgesia during their ED stay that they were in substantial enough pain to require an opioid prescription upon discharge. Fractures of the lumbar spine and pelvis had the highest likelihood of an opioid prescription, followed by rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine. This may be because these fracture patterns benefit from a strong analgesic regimen to help decrease complications including pneumonia (as seen in rib fractures) and deconditioning.Reference Holcomb, McMullin, Kozar, Lygas and Moore15-Reference Brasel, Guse, Layde and Weigelt17

Previous studies

Previous studies have shown that there is variability in prescription practices amongst ED providers, even in those practising within the same ED.Reference Barnett, Olenski and Jena5-Reference Hoppe, McStay, Sun and Capp7 One suggestion shown to help standardize prescription practices is the creation of opioid prescription guidelines.Reference Chacko, Greenstein, Ardolic and Berwald11-Reference Beaudoin, Janicki, Zhai and Choo13 To date, there are no validated guidelines on opioid prescriptions for acute musculoskeletal fractures in the ED.

There is also a growing body of literature on the negative side effects of all opioids, including their addictive potential, respiratory depression, and fall risk.Reference Buckeridge, Huang and Hanley18-Reference Miller, Stürmer, Azrael, Levin and Solomon20 Tramadol, previously marketed as a weak opioid, has been shown to have similar addictive profiles as those of other opioids, an unfavourable side effect profile, and an increase in all-cause mortality.Reference Zeng, Dubreuil and LaRochelle21.Reference Chen, Chen and Knaggs22

Strengths and limitations

One strength of this study was the large, two-site sample of patients with well-defined patient data. This allowed us to capture a variety of injuries and analyze prescription patterns of over 130 staff and resident physicians. One limitation of this study is the lack of follow-up. As such, we are unable to discern the appropriateness of the analgesic plan. However, given that this study primarily sought to look for variability in the amount and type of opioid prescribed rather than the effectiveness of any given analgesic regimen, this can be looked at in future studies. Moreover, utilizing the ED record of treatment and nursing triage notes to collect data on psychiatric history, substance abuse, and chronic pain does not provide us information on the severity of those comorbidities. Furthermore, as we sought to obtain a consecutive sample of 260 patients discharged with opioid prescriptions, our study captured patients with fractures between January and April. This may introduce bias as different fractures are more prevalent depending on the season. However, this will likely not make a significant difference in the prescription patterns. Within our multivariable analysis, we excluded 13 patients (1.6%) because covariate values were missing. We do not believe these individuals with missing values are different in a way that would alter our conclusions. However, the risk of bias due to missing data cannot be ruled out. Lastly, although our data comes from two campuses of a large tertiary care centre, they exist within the same health network and city and, therefore, may be impacted by regional practices.

Implications

Our study shows that even amongst physicians within the same ED, variability exists in prescription practices for acute musculoskeletal fractures. One contributing factor may be the lack of prescription guidelines in this centre. Our study highlights the need for guidelines to be developed to help standardize practice patterns. Furthermore, our data show some factors associated with a higher likelihood of opioids prescribed, including a lower CTAS score, use of hydromorphone and tramadol during ED stay, and certain fracture types (lumbar spine and pelvis, rib(s), sternum, and thoracic spine). Currently, there is limited data showing these as causative factors. Moreover, tramadol was the second most commonly prescribed opioid, with 86 patients (10.5%) receiving this medication upon discharge. This may be a result of tramadol being marketed as a weak opioid with minimal side effects and being included in the pain directive. Although we did not specifically look at the adverse effects of tramadol, with recent studies showing the negative side effects of tramadol, it may be a medication ED physicians reconsider prescribing.

Future studies on opioid prescription practices may look at which factors result in a higher likelihood of opioids being prescribed. These factors may then help create guidelines to help standardize prescription practices amongst ED physicians. There is also a gap in research for whether analgesic regimens should include adjunctive opioids for musculoskeletal fractures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this health records review looking at ED physician opioid prescriptions for patients discharged with acute musculoskeletal fractures, we found that the majority of patients did not receive opioids. Of those patients who did, there was variation in the type and amount prescribed, with hydromorphone being the most commonly prescribed opioid in a wide range of standard doses. Moreover, few patients returned to the ED for a pain-related visit in one month. Ultimately, we recommend the standardization of opioid prescriptions amongst ED providers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Monica Taljaard for her help with the statistical analysis.

Supplementary material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.50.

Competing interests

None to report.