CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about this topic?

Urine testing is commonly required for infants in the emergency department (ED). Bladder catheterization is often used for specimen collection.

What did this study ask?

How well does a bladder stimulation technique for urine collection perform among infants aged ≤ 90 days in the ED?

What did this study find?

We found the technique to be successful for urine collection in just over half of study subjects.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

This bladder stimulation technique is a reasonable first step approach to obtaining urine specimens for clinically stable young infants in the ED.

INTRODUCTION

Urine testing is a common investigation for young infants in the emergency department (ED). The standard of care for this age group remains bladder catheterization, despite its potential to cause pain, contamination, and iatrogenic urinary tract infections (UTIs).Reference Robinson, Finlay, Lang and Bortolussi1 Meanwhile noninvasive collection using a bagged technique carries too high a risk of contamination.Reference Tosif, Baker, Oakley, Donath and Babl2 A recent study by Herreros Fernández et al. describes a novel bladder stimulation technique to collect midstream urine and reports a high success rate in well-feeding, inpatient newborns.Reference Herreros Fernández, González Merino and Tagarro García3

Our objective was to examine this technique's performance among an ED-based population of infants ≤ 90 days old. This age range represents a high-risk period for infection in infants,Reference Cioffredi and Jhaveri4 for which ED physicians hold a lower threshold for performing urinalyses. To reflect a real-world application of the technique, we assessed its performance among infants with a wide range of clinical presentations and acuities and when performed by a large cohort of health care providers.

METHODS

Study design and setting

We prospectively enrolled a convenience cohort of infants presenting to the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) ED in Ottawa, Ontario, between March 2015 and January 2016. The CHEO Research Ethics Board approved this study. Written, informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT02381834).

Participants

Infants aged ≤ 90 days requiring urinalysis were eligible. Patients were excluded if critically ill (i.e., Pediatric Canadian Triage Acuity Scale Level 1), moderately to severely dehydrated, experiencing significant feeding issues (e.g., suspected pyloric stenosis), presenting with conditions for which the technique would be ill-advised (e.g., injury or infection over bladder stimulation site) or if previously enrolled.

Patient recruitment and data collection

ED staff assessed eligibility, obtained consent, and recorded data regarding feeding/fluid administration, success of urine collection, time required for protocol completion, and time elapsed from bladder stimulation onset to successful urine collection. Following protocol completion, parents/guardians rated their child's level of distress during the procedure. Caregivers and nurses/physicians performing the bladder stimulation attempt also completed a satisfaction survey.

Urine collection procedure

Two persons (including at least one study-trained nurse/physician) performed the procedure, while a third recorded time intervals between protocol steps. The protocol involved a combination of fluid administration and noninvasive bladder stimulation manoeuvres. Infants with no history of poor feeding were fed ad libitum. For infants that fed poorly, supplemental feeding with expressed breast milk or formula was encouraged. Infants with mild clinical dehydration and/or who failed oral feeding were, at the treating physician's discretion, given a 20-mL/kg intravenous (IV) bolus of 0.9% normal saline over 20 minutes. Approximately 20 minutes after feeding or IV fluid bolus, the infant's genitals were cleaned in sterile fashion using low dose (0.05%) chlorhexidine. Infants were then held under the axillae with their legs dangling in a standing-like position. A nurse or physician then began bladder stimulation by gently finger tapping on the lower abdomen just above the pubic symphysis at a frequency of 100 taps/minute. If unsuccessful after 30 seconds, the provider switched to stimulating the lower back in the lumbar paravertebral zones by lightly massaging in a circular motion using both thumbs for a maximum of 30 seconds. These manoeuvres were repeated in succession until voiding occurred or 5 minutes elapsed. Infants who failed to void or had unsuccessful midstream urine capture underwent bladder catheterization at the treating physician's discretion.

Training

Standardized training included a 5-minute demonstration video and 15-minute hands-on practice session led by the principal investigator (T.C.) or a nurse co-investigator (L.S., J.C., K.M.). The video could be reviewed before all stimulation attempts.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was successful midstream urine collection. Success was defined as collection of ≥ 1 mL urine (i.e., the minimum required for routine and microscopic urinalysis) within 5 minutes of bladder stimulation. Secondary outcomes included sample contamination, time for full protocol completion (minutes), bladder stimulation time required for successful urine collection (seconds), patient distress as perceived by parent/guardian using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS), and caregiver and nurse/physician satisfaction with the technique on a yes/no scale. Contamination was a priori conservatively defined as growth of two microorganisms or a single non-uropathogenic organism, irrespective of colony counts, which included urine cultures reported as “no significant growth.” Given the lack of consensus as to what threshold of colony-forming units (CFUs) should define a UTI in young infants,Reference Tzimenatos, Mahajan and Dayan5–Reference Kuppermann, Dayan and Levine7 pure growth of < 10 × 106 CFUs/L of uropathogenic organisms was also considered contamination.

Sample size

Herreros Fernández et al. reported success with their technique for 86.3% (69/80) of inpatient newborns.Reference Herreros Fernández, González Merino and Tagarro García3 Reintroducing 10 patients they excluded for “low oral intake” into their analysis cohort gives a real-world success rate of 76.7% (69/90). Because infants presenting to the ED often have low oral intake, and the technique was to be attempted by many ED staff, we anticipated a 50% success rate. A sample size of 150 infants was calculated to obtain a 95% confidence interval (CI) of ± 8%.

Statistical analysis

Our analysis included all patients in whom bladder stimulation was attempted and whose primary outcome data were complete. Proportions of patients with successful urine collection and with contaminated specimens were calculated with a 95% CI using the Wilson score method. As a subgroup analysis, we examined success and contamination by patient sex, and among males, by circumcision status. Wilson score CI for risk differences was similarly used. For all patients, Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for time to full protocol completion; unsuccessful attempts were considered censoring events. Time required for full protocol completion (i.e., from initiation of feeding) and bladder stimulation time required before successful midstream urine collection were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR). The mean and SD of the VAS reported by caregivers for patient distress was reported with a VAS < 30 mm considered minimal distress.Reference Collins, Moore and McQuay8 Yes/no statements of satisfaction were analyzed by tabulating affirmative responses and computing proportions.

Univariate logistic regression examined whether age, sex, poor feeding, or VAS score were predictors of successful urine collection. Poor feeding was determined by nursing assessment in conjunction with caregiver feedback of oral intake relative to baseline. Twenty participants (13.6%) were missing a VAS score; it was assumed to be missing at random and listwise deletion was used in analysis involving this predictor. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Variables deemed clinically relevant with a two-sided p-value < 0.1 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0.

RESULTS

Staff training

Thirty-six nurses and five physicians were trained in the technique. Overall, 60% (36/60) of the ED nurse workforce participated. Each nurse performed at least one stimulation attempt included in our analysis.

Participants

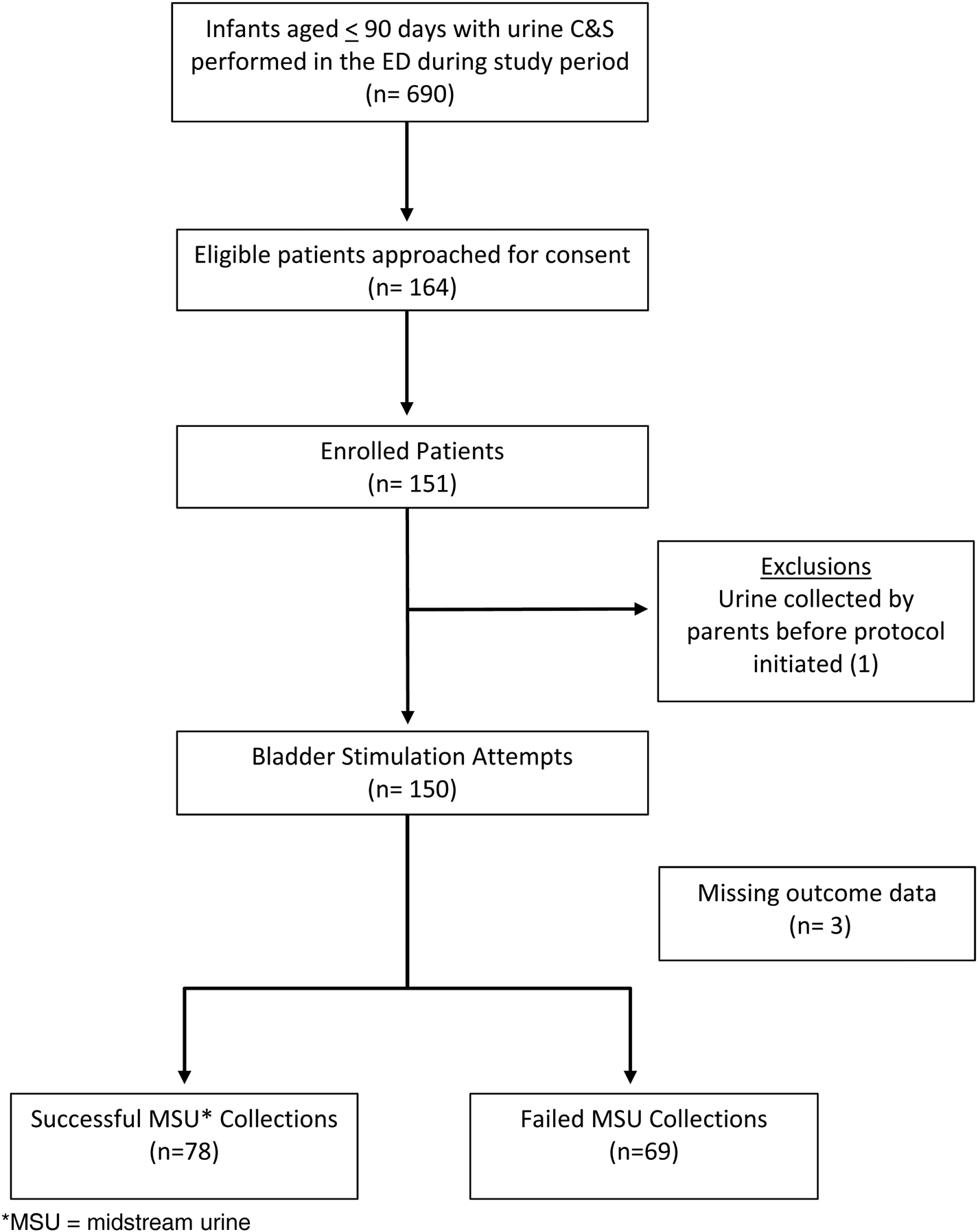

During the study period, trained clinical staff identified 164 eligible infants and approached their caregivers for consent. One hundred fifty-one infants were enrolled; one voided before the procedure and three had no primary outcome data recorded, leaving 147 infants who underwent bladder stimulation included in the analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 describes participants’ characteristics.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

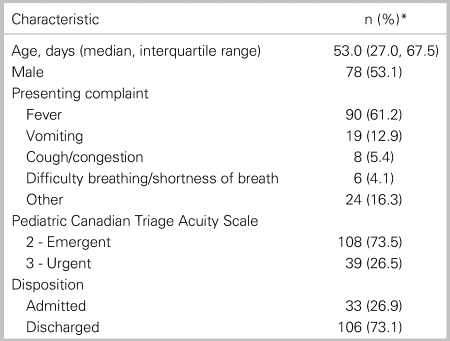

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study patients (n = 147)

* Unless otherwise indicated

Success of bladder stimulation procedure

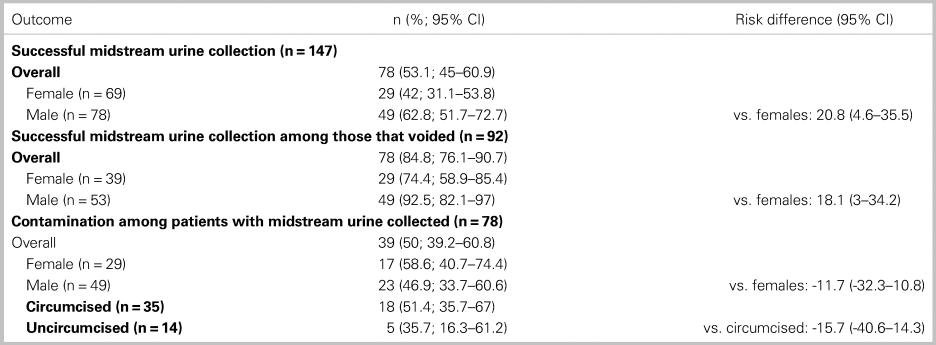

Ninety-two infants (62.6%; 92/147) voided with bladder stimulation; urine collection was successful in 78 of them (53.1%, 95% CI 45–60.9). A higher proportion of males had successful midstream urine collection than females (Table 2). Among the 14 infants who voided with unsuccessful midstream urine collection, 3 produced insufficient volume and for the remainder staff were unable to catch an adequate amount of urine.

Table 2. Success of midstream urine collection and risk of contamination

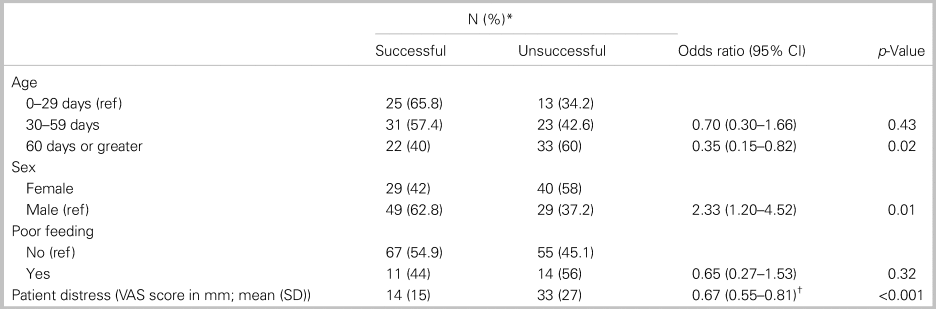

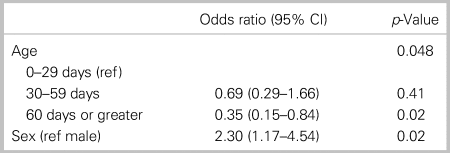

Age, sex, and VAS score were associated with successful midstream urine collection in the univariate analysis (Table 3). Age and sex were found to be significant predictors of success in the multivariate analysis (Table 4). VAS was not included in the multivariate analysis assuming clinicians would only consider variables that were measurable pre-procedure.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of factors associated with successful midstream urine collection

* Unless otherwise indicated.

† For each 10-mm increase in VAS score, the odds of a successful urine collection decreases by 33%.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with successful midstream urine collection

Risk of contamination with bladder stimulation technique

Among the 78 infants with successful urine collection, 39 (50%, 95% CI, 39.2–60.8%) had contaminated specimens. There was no difference in contamination by sex or circumcision status (Table 2). The majority (79.5% [31/39]; 95% CI, 64.4–89.2%) of contaminated specimens were reported as “no significant growth” or “growth of 3 or more organisms” and were, therefore, easily identifiable. Among the 58 infants discharged home after midstream urine collection, 3 were asked to return to the ED for repeat urinalysis due to clinician misinterpretation of urine culture results. Upon review, these samples were clearly contaminated (with very low colony counts of uropathogenic organisms or mixed growth of organisms, following normal urinalyses), and a repeat ED visit was unnecessary.

Bladder stimulation procedural details

For all study patients, the median time for full protocol completion was 32 minutes (IQR, 25–41 minutes). For the 78 infants with successful midstream urine collection, median bladder stimulation time was 45 seconds (IQR, 20–120 seconds). Parents/guardians reported a mean VAS score of 22 mm (SD 23.2 mm) for patient distress. The majority of caregivers (89.7%; 113/126) and health care providers (89.7%; 122/136) reported their experience with the technique as “positive” on the satisfaction survey.

Urinalysis and urine culture results for infants with successful bladder stimulation

Eight infants were diagnosed with UTIs during their ED visit. All had positive urinalyses (leucocyte esterase [LE] positive, nitrite positive, or pyuria with >5 white blood cells per high power field in centrifuged urine). Among these patients, those with a positive LE were strongly positive (≥ 2+). Cultures for these infants grew single uropathogenic organisms (six with >100 × 106 CFUs/L, one with 80 × 106 CFUs/L, and one with 90 × 106 CFUs/L). Three patients had urinalyses with trace LE reactivity only and none were diagnosed with UTIs during their ED visit; urine cultures showed no significant growth (n = 2) or were negative (n = 1). Two patients, a 3-day-old admitted for hyperbilirubinemia and a 70-day-old with fever managed as an outpatient, had negative urinalyses but both cultures were positive with single uropathogenic organisms at >100 × 106 CFUs/L. One patient, an 8-day-old admitted with fever, had a negative urinalysis with 60 × 106 CFUs/L of a single uropathogenic organism on culture.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of findings

Urine testing of young infants is a daily occurrence in the pediatric ED. Finding a safe, easy, and effective method for noninvasively collecting urine in this age group would be a huge step forward in the pursuit of an “ouchless” ED experience.Reference Kennedy and Luhmann9 We pragmatically tested this bladder stimulation technique by enrolling infants requiring urinalysis for a spectrum of clinical presentations and acuities. We also sought to determine how the technique performed when a large cohort of ED staff were trained and tasked with specimen collection, not just a few chosen “experts.” Ultimately, we found the technique to be successful in just over half of all infants. The protocol held greater success with eliciting voiding (62.6%), suggesting there are technical issues that require further optimization to improve specimen capture rates, particularly among females. Overall, the procedure was well tolerated with low reported levels of perceived distress. Caregivers and clinicians reported high levels of satisfaction with the technique.

Comparison to previous studies

Two recent studies examining this technique reported higher levels of success ranging from 78 to 86%; however, neither study used a strict criterion of 1 mL of urine captured in their definition of success.Reference Herreros, Tagarro, Garcia-Pose, Sanchez, Canete and Gili10,Reference Altuntas, Tayfur, Kocak, Razi and Akkurt11 Labrosse et al. studied this technique in an ED setting, enrolling infants up to 6 months old, but only five research personnel performed the procedure.Reference Labrosse, Levy, Autmizguine and Gravel12 Similarly, Tran et al. examined the technique in children up to 2 years old with four ED physicians performing the technique.Reference Tran, Fortier and Giovannini-Chami13 We had a significantly higher number of personnel performing the technique, yet our proportion of success was very similar to theirs (49% and 55.6%, respectively), suggesting that success is unlikely to be dependent on provider expertise. Our study is the first to demonstrate an influence of sex on success.

On a significant and somewhat surprising note, there is currently no international consensus on how best to define urine contamination. We chose a more conservative set of criteria (which are well established in the infectious diseases literatureReference Doern and Richardson14) as compared with the aforementioned studies. Of interest, Herreros et al. used identical criteria and yet had a significantly lower rate of contamination (5% v. 50%).Reference Herreros, Tagarro, Garcia-Pose, Sanchez, Canete and Gili10 This may be a result of the different cleaning materials used for sterilization (i.e., soap and water v. 0.05% chlorhexidine in our study).

A recent, large multi-center prospective study has demonstrated that a positive urinalysis has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of UTIs even among infants aged < 60 days.Reference Tzimenatos, Mahajan and Dayan5 While this study examined urine collected by catherization and suprapubic aspiration, another study comparing urine obtained by clean catch and catherization demonstrated no difference in the sensitivity or specificity of urinalysis for detecting UTIs between these two methods for febrile infants < 90 days old.Reference Herreros, Tagarro, Garcia-Pose, Sanchez, Canete and Gili15 In our study, no patient was incorrectly diagnosed with a UTI on the basis of a positive urinalysis from a midstream urine sample. While three patients with negative urinalyses from midstream urine samples had urine cultures that grew >50 × 106 CFUs/L of a uropathogenic organism, these patients may have had transient bacteruria. Such findings contribute to the ongoing debate in the literature regarding the interpretation of positive urine cultures in the setting of a negative urinalysis.Reference Tzimenatos, Mahajan and Dayan5,Reference Kuppermann, Dayan and Levine7,Reference Schroeder, Chang, Shen, Biondi and Greenhow16–Reference Wettergren and Jodal18

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

There are several strengths to our study. First, our study reflects clinical care in the real-world ED setting. We used liberal eligibility criteria to reflect the breadth of patient presentations and had a large cohort of health care providers participating. We are also the first to survey both caregivers and health care providers regarding their satisfaction with the procedure. Our study was performed in a single tertiary care pediatric ED, so the results may not be as generalizable to community or academic adult-centered EDs where less comfort may exist for performing procedures on infants. The high rate of contamination in midstream urine specimens could potentially lead to unnecessary antibiotic treatment if misinterpreted. Importantly, the overwhelming majority (79.5%) of contaminated specimens were easily identifiable (i.e., reported as “no significant growth” or “growth of 3 or more organisms”). This issue is unlikely to affect a patient's downstream clinical care in terms of requiring re-testing and/or clinical reassessment, especially given the increasing evidence that urinalysis is highly sensitive and specific for UTIs in young infants.Reference Tzimenatos, Mahajan and Dayan5,Reference Herreros, Tagarro, Garcia-Pose, Sanchez, Canete and Gili15,Reference Schroeder, Chang, Shen, Biondi and Greenhow16

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Given that urine collection was successful in over half of patients within 1 minute of bladder stimulation, and that the vast majority of contaminated specimens were easily identifiable with minimal impact on clinical care, we propose this technique as a reasonable first attempt at urine collection in clinically stable infants aged ≤ 90 days in the ED. The time required for this procedure's protocol and its use of ED resources seem feasible when compared with bladder catherization. The “Quick-Wee” method,Reference Kaufman, Fitzpatrick and Tosif19 another recently described clean catch technique, appears to require a similar amount of procedural time as the one we tested.

CONCLUSIONS

Our pragmatic, pediatric ED-based study found this bladder stimulation technique to be well tolerated, successful in midstream urine collection for approximately half of infants aged ≤ 90 days and associated with high levels of satisfaction among health care workers and caregivers alike.

Competing interests

None.

Financial support

The CHEO Research Institute provided peer reviewed grant funding of this project. The funding agency had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. Dr. Amy Plint is supported in part by a University of Ottawa Research Chair.