CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Pyogenic spinal infection diagnostic protocols commonly use C-reactive protein measurements to help inform decisions to obtain spinal imaging.

What did this study ask?

How sensitive were various C-reactive protein cut-offs for pyogenic spinal infection among emergency department adults with neck or back pain?

What did this study find?

Elevated C-reactive protein cut-off values from 10–30 mg/L were sensitive (90.4% to 100%) for pyogenic spinal infection.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

The use of C-reactive protein cut-off values above the upper limit of normal may safely decrease magnetic resonance imaging utilization for spinal infection.

INTRODUCTION

Pyogenic spinal infection includes spinal epidural abscess, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic facet joint, and paravertebral abscess.Reference Babic and Simpfendorfer1,Reference Hadjipavlou, Mader, Necessary and Muffoletto2 Clinicians frequently miss the diagnosis of pyogenic spinal infection on initial presentation.Reference Babic and Simpfendorfer1 Delays in diagnosis are associated with worse neurologic outcomes.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3 Cited reasons for diagnostic failure include that pyogenic spinal infection is an uncommon disease; spinal epidural abscess was present in 1 of every 255 patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with neck or back pain in one prospective study.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3 Another reason for diagnostic delay is the fact that clinical findings alone lack adequate sensitivity to identify pyogenic spinal infection among the many ED patients presenting with the common chief complaints of neck or back pain.4–Reference Moromizato, Harano, Oyakawa and Tokuda8

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute phase reactant, which may be used in conjunction with the history and physical exam to identify patients in need of advanced spinal imaging to evaluate for pyogenic spinal infection.Reference Babic and Simpfendorfer1,Reference Berbari, Kanj and Kowalski9–Reference Babic, Simpfendorfer and Berbari11 Published diagnostic cut-offs for CRP to prompt spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) range from 3 to 100 mg/L, but no particular threshold value has yet gained widespread acceptance.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3,Reference Berbari, Kanj and Kowalski9,Reference Jean, Irisson and Gras12,Reference Harris, Caesar, Davison, Phibbs and Than13 The most commonly cited CRP diagnostic cut-off in ED literature is any elevation beyond the upper limit of normal, commonly 3 mg/L.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3,Reference Alerhand, Wood, Long and Koyfman14 This diagnostic cut-off has high sensitivity for pyogenic spinal infection at the expense of lower specificity.Reference Jean, Irisson and Gras12 Providers face a difficult challenge of reducing missed diagnosis of pyogenic spinal infection without overutilizing MRI resources, as one ED study found that 93% of spinal MRI investigations for evaluation of spinal infection were negative.Reference El Sayed and Witting15 The optimal CRP threshold must then balance both the priorities of sensitivity and specificity.

The objective of this study was to describe the sensitivity of various CRP cut-off values in identifying ED patients requiring urgent spinal MRI evaluation for pyogenic spinal infection among adults presenting to the ED with neck or back pain concerning possible pyogenic spinal infection.

METHODS

Study design and time period

This secondary analysis of a single-centre, prospective cohort study included a convenience sample of adults (≥ 17 years old) presenting to the ED from January 2004 to August 2018 with neck or back pain in whom the ED provider had a clinical suspicion for pyogenic spinal infection. We enrolled a derivation cohort from January 2004 to March 2010 and a validation cohort from April 2010 to August 2018. The study setting was a Southwestern United States community ED with an annual census of approximately 50,000 patients during the investigation period. Treating ED providers, either physicians or physician assistants, contacted the principal investigator by phone upon recognizing the possibility of pyogenic spinal infection for patient enrolment. The principal investigator screened these patients for enrolment, performed focused history and physical examinations related to pyogenic spinal infection, and prospectively collected imaging, laboratory, and outcome data from the medical record. Enrolment depended upon the availability of the principal investigator. Enrolled patients received routine care at our institution. We did not blind providers to CRP results, which were used in clinical decision making as per usual care at our institution. We previously published additional details of enrolment procedures and variable definitions.Reference Davis, April, Mehta, Long and Shroyer16 We adhered to the Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies guidelines in our research design, reporting, and analysis.Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma and Bruns17

Population

Inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 17 years old) presenting to the ED with neck or back pain for possible pyogenic spinal infection to the emergency provider. Possible triggers for enrolment included, but were not limited to, the presence of published historical red flags, fever, neurologic deficits, multiple recent evaluations for neck or back pain, and recent spinal surgery or instrumentation.Reference Reihsaus, Waldbaur and Seeling7 The derivation phase included both patients with and without spinal infection, and the validation phase included only patients with pyogenic spinal infection. Focused history and physical examination by the principal investigator occurred prior to MRI results for nearly all subjects in the derivation phase. The validation phase used the same protocol for patient identification and principal investigator notification, but enrolment and bedside data collection occurred after the diagnosis of spinal infection. We excluded patients presenting to the ED less than 5 days after spinal surgery given a persistent elevation of inflammatory biomarkers during that period regardless of whether infection was present.Reference Rosahl, Gharabaghi, Zink and Samii18,Reference Cornett, Vincent, Crow and Hewlett19 We excluded patients diagnosed with tuberculous or fungal spinal infections to allow comparison of our data to other literature evaluating pyogenic spinal infection. We excluded patients with missing CRP data. The hospital institutional review board at Methodist Hospital System approved the study protocol, and all patients provided verbal consent as per the waiver for documentation of informed consent.

Diagnostic testing

CRP measurements were obtained using commercially available Dimension RXL Chemistry analyser (Dade Behring, Illinois, United States) from 2004 to 2013 and Dimension Vista 1500 AG autoanalyser (Siemens, Washington, D.C., United States) from 2013 to 2019. CRP measurements were reported in units of milligrams per litre. The lower reporting level of CRP at our institution coincided with our upper limit of normal. This value was 3.5 mg/L from 2004 to 2009 and 3.1 mg/L from 2009 to 2019.Reference Bruneel, Dehoux, Barnier and Boutten20 ED physicians did not routinely obtain an erythrocyte sedimentation rate to allow the reporting of this measurement.

Outcome measures

Pyogenic spinal infection included spinal epidural abscess, vertebral osteomyelitis, paravertebral abscess, and septic facet joint.Reference Hadjipavlou, Mader, Necessary and Muffoletto2 We defined pyogenic spinal infection as present if any of three criteria was met: 1) MRI evidence of pyogenic spinal infection per neuroradiologist report, 2) operative evidence of pyogenic spinal infection per operative report, or 3) culture on CT-guided aspiration consistent with pyogenic spinal infection. The use of multiple reference standards reflects the multiple diagnostic modalities used in clinical practice and provided the most accurate categorization of subjects. Two investigators evaluated each neuroradiologist MRI report and adjudicated whether the report indicated presence of pyogenic spinal infection. All patients analysed as negative for pyogenic spinal infection had either a negative spinal MRI or at least 6 months of follow-up through the medical record showing no evidence of pyogenic spinal infection or new neurologic deficits. We excluded patients without pyogenic spinal infection who did not have a spinal MRI or at least 6 months of follow-up in the medical record.

Data analysis

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort evaluating clinical characteristics predictive of spinal infection among adults presenting to the ED with neck or back pain. We derived a highly sensitive cut-off value for CRP by constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and calculating a value to maximize sensitivity with the highest possible specificity.Reference Douma, le Gal and Sohne21 We calculated diagnostic test characteristics for this derived cut-off, two cut-off values from pyogenic spinal infection literature, and a cut-off value maximizing both sensitivity and specificity. We validated the sensitivities of these diagnostic cut-off values in a separate cohort which contained only patients with pyogenic spinal infection present. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using STATA (Version 16, StataCorp, College Station, TX). A post hoc sample size calculation with 20% prevalence, 95% expected sensitivity, and CI width of 8% provided a sample size estimate of 143 subjects.Reference Buderer22

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

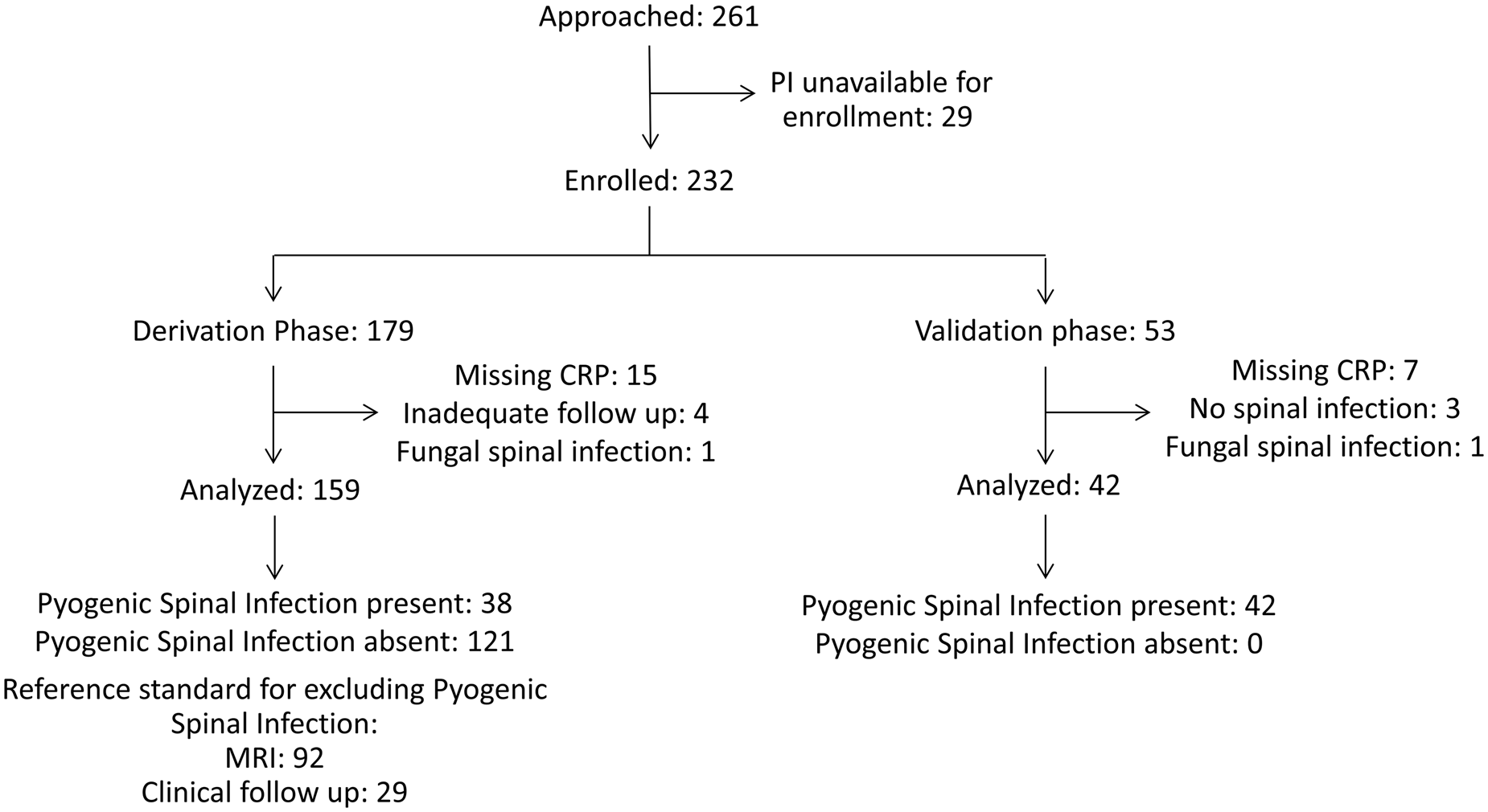

We enrolled 232 patients with 179 patients in the derivation phase and 53 patients in the validation phase. We excluded 31 patients from the analysis (Figure 1). The most common reason for exclusion was missing CRP data (n = 22). Thirty-eight of 159 analysed patients who enrolled between January 2004 and March 2010 in the derivation phase had pyogenic spinal infection, and 25 patients (15.7%) had spinal epidural abscess. The most common diagnosis among patients without pyogenic spinal infection was nonspecific back pain (52.2%), followed by non-spine diagnoses (10.7%), such as pneumonia or pyelonephritis (Table 1).

Figure 1. Patient flow diagram.

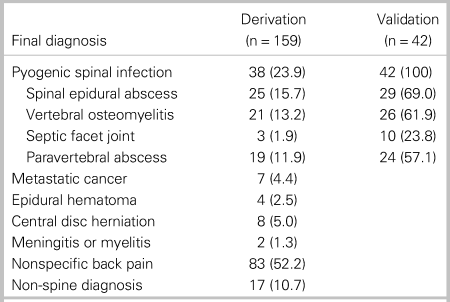

Table 1. Final diagnosis of 201 analysed patients

All data are presented as number (%).

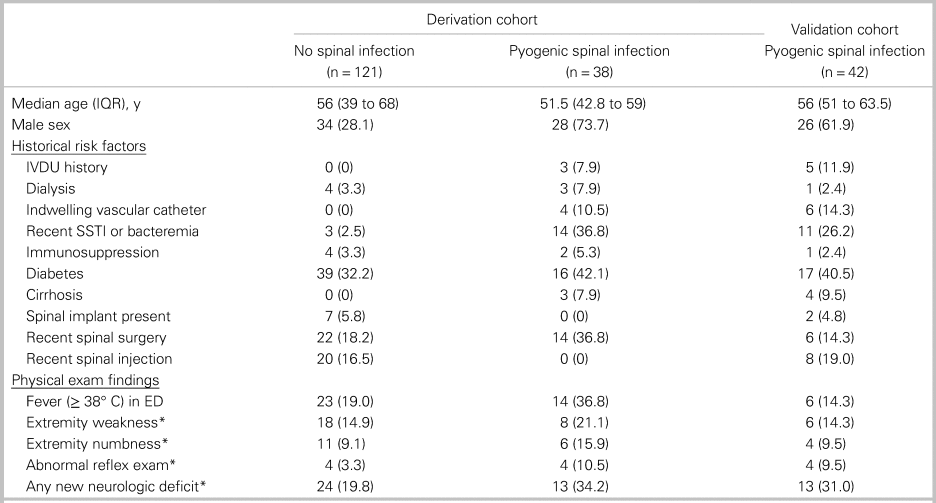

The median age was 55 years (interquartile range [IQR] 40 to 66) for the derivation cohort (n = 159) and 56 years (IQR 51 to 63.5) for the validation cohort (n = 42). In the derivation cohort, 39.0% of patients were male and 22.6% of patients had spinal surgery within the 90 days prior to enrolment (Table 2). Among patients with spinal infection, a minority had intravenous (IV) drug use history (7.9% in derivation and 11.9% in validation cohorts) or had fever at any time in the ED (36.8% in derivation and 14.3% in validation cohorts).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics

All data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

IQR = interquartile range; IVDU = intravenous drug use; SSTI = skin and soft tissue infection.

*Neurologic deficits were only counted as present if assessed to be acute by the principal investigator.

CRP findings

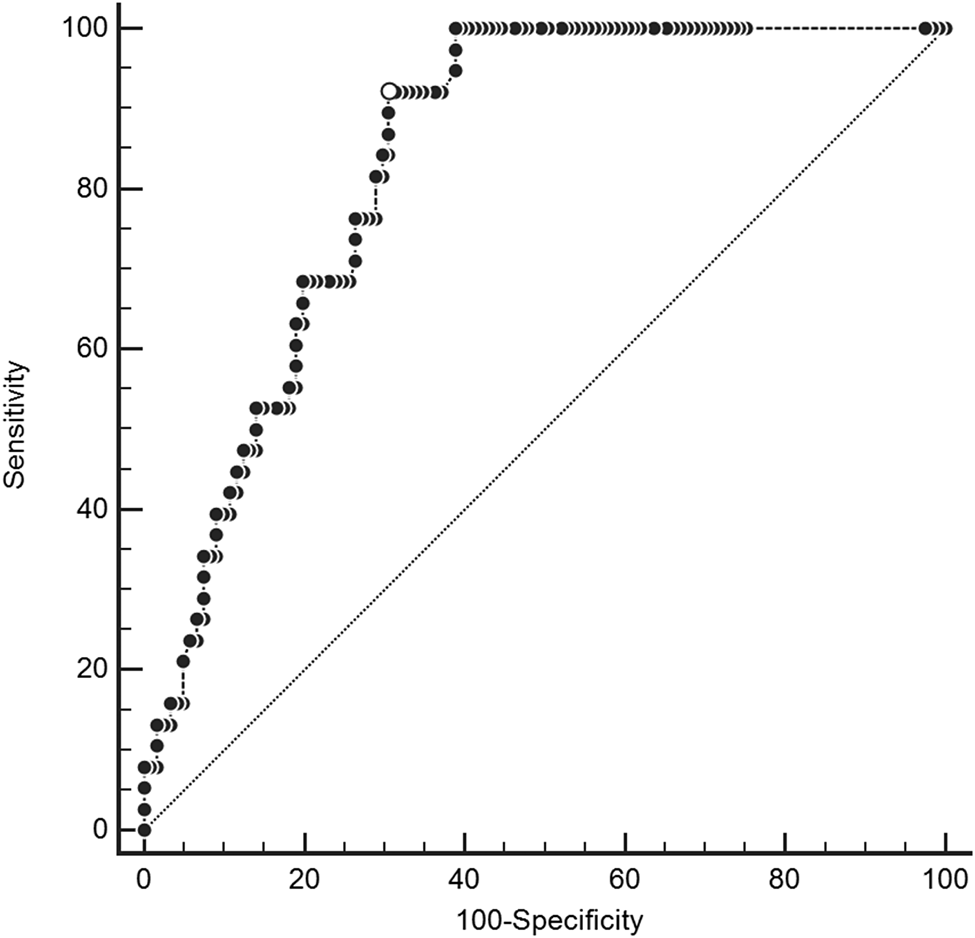

Median CRP values in the derivation cohort were 120.0 mg/L (IQR 67.7 to 172.5 mg/L) among patients with spinal infection versus 14.0 mg/L (IQR 3.8 to 78 mg/L) among patients without spinal infection. In the derivation cohort, the area under the ROC curve for CRP was 0.83 (Figure 2). Online Appendix Figure 1 shows the distribution of CRP values stratified by the presence of spinal infection in the derivation and validation cohorts.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic curve for C-reactive protein in derivation cohort.

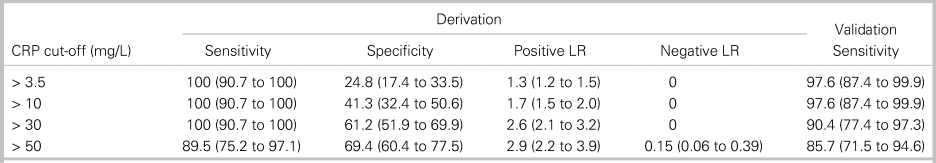

We analysed four diagnostic cut-offs for CRP (Table 3). The upper limit of normal (> 3.5 mg/L at our institution) and mildly elevated CRP (> 10 mg/L) are commonly cited cut-off values.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3,Reference Artenstein, Friderici and Holers23,Reference Bernard, Dinh and Ghout24 CRP > 30 mg/L was selected as a cut-off maximizing sensitivity with a rounded value of 10 times the upper limit of normal (3.1 mg/L) on many analysers. CRP > 50 mg/L was the rounded value of the cut-off maximizing both sensitivity and specificity. CRP > 30 mg/L had 100% sensitivity (95% CI, 90.7% to 100%) in the derivation cohort and 90.4% sensitivity (95% CI, 77.4% to 97.3%) in the validation cohort (see Table 3). Among the four patients with CRP ≤ 30 mg/L in the setting of spinal infection, two patients (50%) were on antibiotics at the time of ED arrival, and four patients (100%) had abnormal findings on neurologic examination. Online Appendix Figure 2 provides the sensitivity of CRP cut-offs from 3.5 mg/lLto 100 mg/L in the derivation and validation cohorts.

Table 3. Diagnostic characteristics of four cut-off values for C-reactive protein

All data are presented as percentage (95% CI).

LR = likelihood ratio.

Considering only pyogenic spinal infection diagnoses as a positive study, 92 patients in the derivation cohort had negative spinal MRI scans. The number of MRIs potentially avoided for each CRP cut-off value was 21 studies (22.8% of negative studies) for CRP > 3.5 mg/L, 38 studies (41.3%) for CRP > 10 mg/L, and 53 studies (57.6%) for CRP > 30 mg/L.

DISCUSSION

Current expert opinion for obtaining urgent or emergent spinal MRI evaluation for pyogenic spinal infection in ED patients relies on historical risk factors, physical exam findings, and inflammatory biomarkers, including CRP.Reference Edlow10,Reference Babic, Simpfendorfer and Berbari11,Reference Pope and Edlow25 The usual recommended cut-off value for CRP is the upper limit of normal, commonly > 3.1 mg/L.Reference Davis, Salazar, Chan and Vilke3 Elevated CRP cut-off values of > 10 mg/L and > 30 mg/L maintained 100% sensitivity in our derivation cohort of an adult ED population with a low prevalence of IV drug use. CRP > 30 mg/L lacked adequate sensitivity (90.4%) in the validation cohort; however, CRP should not be used in isolation to prompt spinal MRI for infection evaluation. All four patients with spinal infections and CRP < 30 mg/L had neurologic deficits on exam to prompt MRI. While spinal MRI may be indicated for emergent diagnoses other than pyogenic spinal infection and CRP should not be the sole diagnostic marker determining imaging decisions, use of 10 mg/L and 30 mg/L CRP cut-off values may have avoided up to 18.5% and 34.8% of negative MRI studies, respectively, in our derivation cohort compared with an upper limit of normal CRP cut-off.

Our findings are consistent with data from multiple recent studies that CRP concentrations in pyogenic spinal infection are usually elevated well beyond 3 mg/L. A recent prospective cohort of 88 patients with vertebral osteomyelitis had a mean CRP of 140 mg/L.Reference Jean, Irisson and Gras12 A randomized controlled trial of 351 patients with vertebral osteomyelitis had a mean CRP of 122 mg/L, and 90.6% of patients had CRP > 10 mg/L.Reference Bernard, Dinh and Ghout24 In contrast to the aforementioned studies, only 81.2% of patients had CRP > 3 mg/L in a retrospective cohort of 166 patients with spinal epidural abscess.Reference Artenstein, Friderici and Holers23 CRP may be less sensitive for pyogenic spinal infection associated with IV drug use, with one study finding a 71.6% sensitivity for CRP greater than the upper limit of normal.Reference Ziu, Dengler, Cordell and Bartanusz26

LIMITATIONS

Our study represents a convenience sample and is subject to spectrum bias by potentially missing patients with less severe disease and no diagnostic workup for spinal infection. The generalizability of our single-centre study to other settings is unknown, particularly in clinical settings with higher prevalence of IV drug use. The validation cohort included only positive cases, so we are unable to calculate specificity for this cohort. PI knowledge of MRI results is a possible source of bias for history and physical exam data in the validation cohort. We collected data over an extended period of time, so changing practice patterns, patient characteristics, or pathogen characteristics may have led to an evolution of the cohort over time. Specifically, advancements in MRI technology may have enabled a diagnosis of a less severe disease in later years of the study. Also, we had missing data for multiple clinically relevant variables to include duration of symptoms, recent visits for back pain, or recent antibiotic use. Our study may overestimate the sensitivity of CRP due to incorporation bias given the lack of provider blinding to CRP data. Mitigating factors for this potential source of bias included strict criteria for excluding spinal infection and lack of literature consensus for a specific CRP cut-off value during the study period.Reference Harris, Caesar, Davison, Phibbs and Than13 We lack sufficient erythrocyte sedimentation rate data to compare the diagnostic characteristics of erythrocyte sedimentation rate versus CRP.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Clinicians cannot use CRP indiscriminately or in isolation because many conditions cause elevated CRP.Reference Clyne and Olshaker27 Our study examined a patient population with clinical concern for pyogenic spinal infection, and the application of CRP in the broader population of back pain would decrease specificity. Multiple conditions, such as cirrhosis or recent use of antibiotics, are associated with decreased CRP concentrations.Reference Khan, Smith, Rao and Donaldson28–Reference Silvestre, Coelho and Póvoa30 Clinicians should consider use of lower CRP cut-off values in patients with these conditions. In our cohort, half of the patients with pyogenic spinal infection and relatively low CRP elevations (≤ 30 mg/L) were on antibiotics prior to arrival, and each patient had abnormalities on neurologic exam to prompt spinal imaging. Close attention to units is necessary when interpreting CRP reports both clinically and in the literature. While many laboratories report an upper limit of normal of 3.1 mg/L, other institutions report an upper limit of normal of 0.3 mg/dL. The recommendation to use a cut-off of 10 times the upper limit of normal can be easily and consistently applied in various clinical settings reporting different units. If externally validated in other ED settings, the use of elevated CRP cut-off values in conjunction with history and physical exam findings to trigger MRI may safely decrease MRI utilization in the ED diagnostic workup of pyogenic spinal infection.

RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

External validation of elevated CRP cut-off values of 10 mg/L and 30 mg/L should analyse test characteristics of these elevated cut-off values in other ED populations. Diagnostic algorithms incorporating these cut-off values should assess whether specificity can be improved while maintaining adequate sensitivity for pyogenic spinal infection.

CONCLUSION

CRP cut-off values above the upper limit of normal had high sensitivity for pyogenic spinal infection in this adult ED population with low prevalence of IV drug use. Clinicians should be cautious in applying elevated CRP cut-offs in patients with IV drug use or conditions associated with decreased CRP values, such as cirrhosis or recent antibiotic use. Elevated CRP cut-off values of > 10 mg/L and > 30 mg/L require validation in other settings.

Supplementary material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.402.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank providers with Greater San Antonio Emergency Physicians for identifying study subjects.

Competing interests:

None declared.

Disclaimers

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the 4th Infantry Division, the Fort Carson Post Command, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, and Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The views of the stated manufacturers are not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Air Force. No Federal endorsement of the stated manufacturers is intended. The voluntary, fully informed consent of the subjects used in this research was obtained as required by 32 CFR 219 and DODI 3216.02_AFI 40–402. This original contribution has not been published, it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder.