1. Introduction

The experimental, historical, and theoretical literatures have identified a range of properties that allow a morphosyntactically singular noun phrase to antecede the pronouns they, them and their, what we refer to henceforth as singular they.Footnote 1 A recurring intuition expressed in much of this literature is that bound-variable singular they as in (1a) is more acceptable than a referential use (1b) for many speakers.

(1)

a. Every lawyer made their case successfully.

b. The lawyer made their case successfully.

This intuition has been confirmed by the most comprehensive experimental work to date on singular they, a large-scale acceptability judgment study by Conrod (Reference Conrod2019). Conrod asked participants (N=754) to rate singular they with different antecedent types (proper noun, generic and quantified) and collected several participant variables (age, gender, and transgender identity). Conrod found evidence of a change in progress: younger participants gave higher ratings to singular they with referential, proper-noun antecedents than older participants, whereas there was no such age effect for the acceptability of singular they with generic or quantified antecedents. Conrod (Reference Conrod2019) additionally found several complex interactions between age and gender, with non-binary and transgender participants generally rating referential they higher. A similar general advantage for bound-variable singular they has been found by Camilliere et al. (Reference Camilliere, Izes, Leventhal and Grodner2019). These studies illustrate a clear asymmetry: bound-variable singular they is widely rated as acceptable across speakers, while referential singular they shows greater variation.

Where things become yet more interesting is the interaction between gender and quantification. Not only is bound-variable singular they highly acceptable to all speakers, there is some evidence that this holds even with gendered antecedents, unlike referential singular they. The historical record contains attestations of singular they bound by gendered antecedents like man (2a) and sister (2b).Footnote 2

(2)

a. There's not a man I meet but doth salute me/As if I were their well-acquainted friend (Shakespeare, A Comedy of Errors, 1623)

b. Both sisters were uncomfortable enough. Each felt for the other, and of course for themselves[.] (Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 1813)

In the theoretical syntax literature (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2017, Konnelly and Cowper Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020), such cases are taken to be on par with non-gendered quantified singular they – that is, as grammatical for all English users.

We set out to investigate the interplay between antecedent gender and whether singular they is bound or referential, examining the consequences for the linguistic representation of singular they and for theories of the incremental processing of pronouns. We found that bound-variable singular they is indeed rated as more acceptable than referential singular they, even with gendered antecedents. However, in two self-paced reading studies we found that these differences in acceptability did not entirely translate to processing advantages: bound-variable singular they offered a processing advantage over referential singular they only with gendered antecedents. Otherwise, bound and referential singular they actually both showed processing disadvantages compared to she/he.

What is particularly interesting about these results is that the processor is differentially sensitive to gender depending on whether they is bound or referential. It has been shown that readers are sensitive to mismatches in the gender of a pronoun and available antecedents, even when there is just one antecedent available (Osterhout and Mobley Reference Osterhout and Mobley1995, Carreiras et al. Reference Carreiras, Garnham, Oakhill and Cain1996). When there is a mismatch, it registers as a processing difficulty, either because of a clash in features or because the pronoun is unheralded and the reader is required to accommodate a new referent that may not be readily available. The question is what features they has such that it will or will not trigger a mismatch.

We explore how different theories of the featural representation of they could account for the processing profile we find. Ultimately, none of these capture the full range of offline and online data we collected. We offer in the final section of this article an alternative formal analysis that distinguishes the way in which gender features are represented on quantified versus referential antecedents. We follow a view suggested in the semantics literature, and closely related to the proposal in Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020), that quantified antecedents invoke different representations than do referential antecedents. Both antecedents bear formal indices (indicated by numerals such as ![]() $[ 1 ] $) which are shared by co-referential and bound pronouns. However, indices are represented and interpreted differently for quantified phrases and referential phrases. In the case of quantified phrases, the index is parsed separately from the quantified phrase as a simple index (Heim and Kratzer Reference Heim and Kratzer1998) which we will argue optimally bears no gender features, even if the quantified noun phrase itself does. (For convenience we represent gender as the feature [GENDER

$[ 1 ] $) which are shared by co-referential and bound pronouns. However, indices are represented and interpreted differently for quantified phrases and referential phrases. In the case of quantified phrases, the index is parsed separately from the quantified phrase as a simple index (Heim and Kratzer Reference Heim and Kratzer1998) which we will argue optimally bears no gender features, even if the quantified noun phrase itself does. (For convenience we represent gender as the feature [GENDER![]() $] $ below.)

$] $ below.)

(3) Quantified antecedent index:

$[ $Every womangender,sg]

$[ $Every womangender,sg]  $[ $ 1

$[ $ 1  $[ $ did their

$[ $ did their $_1$ homework

$_1$ homework  $] ] $

$] ] $

In contrast, the index on a referential antecedent is parsed as part of the DP, bundled together with any number or gender features associated with the noun.

(4) Referential antecedent index:

$[ $The woman]1,gender,sg

$[ $The woman]1,gender,sg  $[ $ did their

$[ $ did their $_1$ homework

$_1$ homework  $] $

$] $

The idea is that when a pronoun retrieves a referential antecedent, it retrieves all the features in this bundle. We will argue this leads to a clash in a situation like (4) on the view that singular they bears (enriched) negative vales for gender ([-GENDER]) for some speakers. What is retrieved in bound variables, we suggest, is not the quantified noun phrase itself, but the gender-free index, and bearing no gender feature this does not mismatch with the features of they. This proposal has the advantage of holding constant the features of they, while at the same time allowing for the fact that they is differentially sensitive to gender depending on whether it is bound or referential. While we will ultimately remain uncommitted about how these formal representations are fully integrated in a theory of sentence processing, we think our contribution highlights the value of combining insights from the formal literature with those of processing theories.

2. Background

This section reviews the previous formal linguistic literature and processing studies on singular they that serve as background to the work presented here.

2.1 Singular they in the formal syntax-semantics literature

The use of singular they is undergoing a number of changes in present-day English. What remains invariable, it seems, is that bound-variable uses are readily accepted and have been for centuries. Furthermore, as noted above, there is some evidence that bound-variable singular they is possible with antecedents of any gender for even the most conservative speakers. We verify this in the acceptability studies reported below. Referential singular they, on the other hand, is subject to a great deal more variation and nuance. Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020) identify three stages in the expanding use of referential singular they. In stage 1, which is that of the most conservative speakers, referential singular they is used as an epicene pronoun as in (5).

(5) Shhh! The person on the phone with me has lost their voice.

In these scenarios the gender of the referent may be unknown or indeterminate (Bodine Reference Bodine1975, Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2017) or irrelevant to the communicative goals of the speaker (Moulton et al. Reference Moulton, Han, Block, Gendron and Nederveen2020). For stage 1 speakers, referential singular they is not possible with referents where a form expressing binary gender is both appropriate and known. Such speakers also do not allow singular they with antecedent nouns that are gendered (e.g., sister). In later stages, speakers use referential singular they with referents and antecedents of any gender.Footnote 3

A critical component of the analyses in Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020) as well as Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman2017) is that morphosyntactic features may be contrastive or non-contrastive. If a feature is contrastive in a system, then its absence implies the negation of that feature (or the property that feature represents). For stage 1 speakers, the morpho-syntactic gender features [MASC] and [FEM] are contrastive. Since singular they lacks both such features, it implies that gender is unknown or irrelevant. We will describe this as the epicene implicature. In later stages, with more innovative speakers, gender features become non-contrastive. The absence of a non-contrastive feature does not trigger the epicene implicature and so they becomes felicitous in a wider range of discourse contexts with a wider range of antecedent types.

What is of central importance to our studies is the difference between bound and referential singular they in the grammar of speakers for whom gender is contrastive. An adequate theory needs to ensure that gender is rendered non-contrastive on bound variables but remains contrastive on referential singular they for conservative speakers (assuming this is the correct description of the facts, which we do verify in Experiments 1a and 2a). Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman2017) follows Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) in postulating that bound pronouns may have a smaller structure than referential pronouns. In Bjorkman's (Reference Bjorkman2017) analysis, bound-variable singular they can exclude the projection (![]() $\phi$P) that houses gender features. We interpret Bjorkman's proposal in the following way: when

$\phi$P) that houses gender features. We interpret Bjorkman's proposal in the following way: when ![]() $\phi$P is itself entirely absent, the absence of a specific gender feature does not trigger the epicene implicature. Referential pronouns, in contrast, must include

$\phi$P is itself entirely absent, the absence of a specific gender feature does not trigger the epicene implicature. Referential pronouns, in contrast, must include ![]() $\phi$P; if no specific gender feature is present on

$\phi$P; if no specific gender feature is present on ![]() $\phi$P, then the epicene implicature arises. In a related proposal, Conrod (Reference Conrod2019) argues that bound pronouns, unlike referential pronouns, do not involve N movement to D, where gender features are located. Both approaches distinguish bound vs. referential singular they in terms of the structure of the pronoun itself.

$\phi$P, then the epicene implicature arises. In a related proposal, Conrod (Reference Conrod2019) argues that bound pronouns, unlike referential pronouns, do not involve N movement to D, where gender features are located. Both approaches distinguish bound vs. referential singular they in terms of the structure of the pronoun itself.

For Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020), the bound–referential contrast comes out of differences in the type of antecedent involved. They propose that the entire DP in a quantified antecedent need not inherit the gender features of its common noun restrictor, even if it bears contrastive gender features for Stage 1 English users. The entire DP of a referential antecedent, on the other hand, must bear the gender features of the head noun. Coupled with the additional requirement that “coreference requires that the features of the pronoun match those of its [entire DP] antecedent”, singular they will not be possible with a gendered referential antecedent but will be with a gendered quantifier antecedent.

In addition to gender features, the number feature of singular they needs to be addressed. From a morpho-syntactic point of view, singular they does not bear a singular feature (note that it always triggers subject-verb agreement appropriate for a notional plural: every/the person said they are/*is here). One possibility is that they, whether interpreted as singular or otherwise, never bears a singular feature (Sauerland et al. Reference Sauerland, Anderssen, Yatsushiro, Kepser and Reis2005). While number is not a dimension along which we manipulated the stimuli of the studies reported below, both for concreteness and to limit the hypothesis space, we follow Sauerland et al. in taking they to be inclusive of both plural and singular denotations and in never bearing a morphological or semantic singular feature.

In the next section we turn to psycholinguistic studies which examine the relationship between singular they and its antecedent in terms of processing difficulty. Here the precise featural make-up of they becomes crucial. We lay out various expectations for processing depending on assumptions about the linguistic representation of they. We review the existing evidence in light of these expectations, motivating the experiments to follow.

2.2 Modelling the processing of singular they

A number of studies have investigated whether the processor has difficulty when they retrieves either a singular antecedent or a gendered antecedent. Underlying these studies are assumptions about what features singular they does or does not carry in the first place, such that they would ever cause mismatches. As we saw in the last section, it is not trivial to identify what features they carries and this makes it difficult to make concrete processing predictions. In the following subsections, we outline predictions generated by two different approaches to the gender and number features of they and then measure them against the existing processing literature.

As for the crucial distinction between bound and referential they, pronouns in English do not carry features that identify them as bound or referential. Nonetheless, since bound-variable singular they is the one most widely available across speaker populations, even potentially with gendered antecedents, we might expect processing advantages for such cases. In fact, it has been proposed that for pronouns in general the processor prefers bound interpretations over referential ones (Grodzinsky and Reinhart Reference Grodzinsky and Reinhart1993), although there is no consensus (Frazier and Clifton Reference Frazier and Clifton2000, Carminati et al. Reference Carminati, Frazier and Rayner2002, Koornneef Reference Koornneef2008, Koornneef et al. Reference Koornneef, Avrutin, Wijnen, Reuland and Runner2011, Cunnings et al. Reference Cunnings, Patterson and Felser2014). Koornneef (Reference Koornneef2008) found that Dutch pronouns were more likely to retrieve quantified over referential antecedents. However, Cunnings et al. (Reference Cunnings, Patterson and Felser2014) report no such preferences for English, finding instead merely a preference for recency. The question for singular they is whether a quantified antecedent offers any advantage in incremental processing, over and above any potential advantages for bound pronouns generally. We discuss an ambiguity theory of bound versus referential they below that makes this a viable prediction.

2.2.1 Underspecification hypothesis

It has been repeatedly argued that the processing of they in all its uses is different from the processing of other pronouns, including singular he/she/it. In particular, there is some evidence that he/she/it pronouns place a more immediate pressure on the processor to find an antecedent and that they take more resources than they. Moxey et al. (Reference Moxey, Sanford, Sturt and Morrow2004) found earlier disruptions in the reading of she/he lacking a salient singular antecedent compared to they lacking a salient plural antecedent. They suggest that the processor does not as immediately need to resolve the antecedent of they “possibly because they can refer to a wider range of antecedent types than he/she can”. Using ERP methods, Filik et al. (Reference Filik, Sandford and Leuthold2008) found evidence of a cost for unheralded she/he but not for they. Sanford et al. (Reference Sanford, Filik, Emmott and Morrow2008) found that so-called institutional they, which needs no antecedent at all (in referring to implied agents) created no processing costs either. These authors suggest that they is an underspecified pronoun, and so will tolerate a wide range of antecedent types. These expectations are often couched in a shallow or good-enough processing model (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Bailey and Ferraro2002), where they would pose no immediate processing difficulty but might require greater resources in later processing (Moxey et al. Reference Moxey, Sanford, Sturt and Morrow2004).

If they is indeed underspecified, we may not expect the retrieval of singular or gendered antecedents to pose any processing difficulty, at least in early processing. Moreover, without specifying anything further regarding the difference between bound and referential pronouns (but see below) we do not expect a processing advantage for bound over referential they.

2.2.2 Enriched specification hypothesis

Another logical possibility is that they is specified in some way. We think that the theoretical literature makes some possibly testable predictions in light of the notion of contrastive features outlined in the last section. The absence of gender and number features on they may allow the processor to enrich the features of they to include the negative values of these features, that is, ![]() $[ $-SG

$[ $-SG![]() $] $ and

$] $ and ![]() $[ $-MASC

$[ $-MASC![]() $] $ and

$] $ and ![]() $[ $-FEM

$[ $-FEM![]() $] $. Such ‘enriched’ features would then clash with a singular antecedent or a gendered antecedent. We intend the enriched specification approach to be one in which the negative values are active as soon as the processor encounters the pronoun. (Rather than, say, one where the enrichment is delayed; in that case, we would have difficulty distinguishing this from the underspecification approach.) As with the underspecification approach, the enriched specification hypothesis is silent on the difference between bound and referential they.

$] $. Such ‘enriched’ features would then clash with a singular antecedent or a gendered antecedent. We intend the enriched specification approach to be one in which the negative values are active as soon as the processor encounters the pronoun. (Rather than, say, one where the enrichment is delayed; in that case, we would have difficulty distinguishing this from the underspecification approach.) As with the underspecification approach, the enriched specification hypothesis is silent on the difference between bound and referential they.

2.2.3 Referential vs. bound they: ambiguity hypothesis

The above two options concern the role of number and gender. In terms of the bound–referential dimension, we have seen formal theoretical proposals that potentially make interesting processing predictions. As noted above, both Conrod (Reference Conrod2019) and Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman2017) suggest that bound-variable singular they has a smaller, simpler structure than referential singular they. That means they is essentially ambiguous. Upon encountering they, readers may access the simplest representation, which is one that is predisposed toward finding a quantified antecedent.Footnote 4 In this case we might expect a processing advantage for bound singular they over referential singular they whether the antecedent is gendered or not.

While this particular framing of the ambiguity approach predicts an advantage for bound they, it does not make predictions about any interactions with gender or number. The two approaches to gender/number outlined above treat bound and referential singular they equally. There is a more complex option on the market that we think deserves consideration. One interpretation of the proposal in Bjorkman (Reference Bjorkman2017) is that only referential they is enriched with the negative values (since it carries the node that in principle could carry gender features) and hence only it will give rise to feature clashes with a gendered singular antecedent. Bound they, on the other hand, would not be enriched, and so would enjoy both an advantage with quantified antecedents and would show no clash with a gendered antecedent. Similar considerations hold for number.

The reports in the formal literature suggest we might find a processing profile consistent with the complex version of the ambiguity hypothesis outlined above: (i) overall that bound singular they has a processing advantage over referential singular they and (ii) that bound singular they has an advantage over referential singular they with gendered antecedents.

2.3 Previous studies on processing singular they

The experimental record concerning the processing of bound and referential singular they is mixed, in part because the extant studies ask rather separate questions and few make explicit assumptions about the featural content of they. Doherty and Conklin (Reference Doherty and Conklin2017) investigated the role of the gender stereo-typicality of antecedents, all referential. Participants in their study showed processing difficulty of they with gendered antecedents but no cost for non-gendered antecedents.

Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) investigated the impact of both gender and the quantificational status of the antecedent. They measured participants’ reading times for passages such as those in (6), where an indefinite antecedent was gender stereotyped (a truck driver, as in (6a)), non-gendered (a runner, as in (6b)) or was the bare quantifier anybody, as in (6c).

(6) Stimuli from Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997), Experiment 1

a. A truck driver should never drive when sleepy, even if he/she/they may be struggling to make a delivery on time

$\ldots$

$\ldots$b. A runner should eat lots of pasta the night before a race, even if he/she/they would rather have a steak

$\ldots$

$\ldots$c. Anybody who litters should be fined $50, even if he/she/they cannot see a trashcan nearby

$\ldots$

$\ldots$

In whole-sentence reading times, sentences containing they were read as fast as the sentences containing a pronoun congruent with the gender of the antecedent. With the bare quantifier anybody in (6c), they actually afforded a reading time advantage over he and she. In a second experiment, Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) tested referential gendered antecedents (that truck driver) and found that the sentences with they were read more slowly than those with the gender-matching singular pronoun, but with non-gendered referential antecedents (that runner) they was read as quickly as the singular gendered pronouns. Overall, the results suggest that they can resolve to both singular quantified antecedents and non-gendered, singular referential antecedents without apparent difficulty. This outcome is compatible with the underspecification hypothesis for number at least (although they did not compare singular and plural antecedents). Gender, however, appears to cause processing difficulties, but only for referential antecedents. As we saw, neither the underspecification nor the enriched specification hypotheses alone predict this interaction. The processing profile that emerges from these studies is potentially consonant with the complex ambiguity hypothesis we outlined above: bound singular they does not give rise to enriched features specifying negative gender values, unlike referential they, and so we do not expect a feature clash in the former.

Caution should be taken in interpreting Foertsch and Gernsbacher's studies. First, they do not directly compare referential vs. bound singular they with gendered antecedents in one study. Furthermore, Foertsch and Gernsbacher used a whole-sentence self-paced reading methodology, where each sentence was presented successively in its entirety, making it difficult to locate processing difficulty. One of the key contributions of our studies is to determine whether there is an interaction between gender and quantification in the processing of they in a single word-by-word self-paced reading study.

We have further reasons to expect that we might find such an interaction. Ackerman (Reference Ackerman2018) compared sentences employing themself with gendered and non-gendered antecedents, finding a processing advantage using eye-tracking while reading for both the gendered indefinite (a mechanic) and the bare indefinite (someone) compared to specific antecedents (i.e., proper names of different gender bias). Again, the results for gendered indefinites, which can be interpreted as quantificational, fit with the observations in the formal literature that gender interacts with the quantificational vs. referential status of the antecedent, suggesting that bound singular they is ‘genderless’ compared to referential singular they.

The studies cited above manipulated the gender of the antecedent. Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007) investigated the possible clash of number between they and a singular antecedent. They suggest that they is not initially tolerant of singular antecedents, but the singular antecedent can be subsequently “accommodated in some way” (Sanford and Filik Reference Sanford and Filik2007: 172). While tracking participants’ eye-movements, Sanford and Filik presented passages like (7) with singular someone or plural some people followed by either them or a singular her downstream.

(7) Stimuli from Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007)

Mr Jones was looking for the station. He saw [someone/some people] on the other side of the road, so he crossed over and asked [them/her] politely

$\ldots$

$\ldots$

Their eye-movement data revealed processing difficulties for they with a singular antecedent, suggesting that they initiates a search for plural antecedents and when the search fails, a cost is incurred. This outcome is compatible with a number of ideas concerning the number features of they, including the enriched feature theory elaborated above as long as we allow enriched features to be more defeasible than inherent ones.

One limitation of the experimental studies surveyed above should be emphasized: while suggestive of processing differences between referential and quantified singular they, none systemically control for the difference between bound-variable and referential singular they. All use indefinite antecedents, headed either by an indefinite article (a or some with a noun phrase complement), or a bare indefinite (someone or anybody). Indefinites have a notoriously wide range of interpretations, and debate has existed for decades as to whether they are quantificational, referential, or both (Kamp Reference Kamp, Groenendijk, Janssen and Stokhof1981, Heim Reference Heim1982). A quantificational indefinite is in English usually interpreted existentially and typically requires a licensor, such as negation or a modal. Fodor and Sag (Reference Fodor and Sag1982) argued that there are also referential uses of indefinites, and this position has reached consensus in the semantics literature, although there are debates about how the referential use arises and is modeled (Reinhart Reference Reinhart1997, Winter Reference Winter1997, Kratzer Reference Kratzer1998, Matthewson Reference Matthewson1999, Schwarzschild Reference Schwarzschild2002). In simple episodic sentences like (7), used in Sanford and Filik's (Reference Sanford and Filik2007) study and Doherty and Conklin's (Reference Doherty and Conklin2017) study, the indefinite could most naturally be interpreted as referential.Footnote 5 The stimuli in Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997), on the other hand, are most naturally interpreted with a quantificational interpretation for the indefinite, one in which existential force is interpreted with scope below the deontic modal: (6a) most naturally conveys that it is not compatible with the rules that there exist an x such that if x is a truck driver, x drives when sleepy. Similar remarks apply to the other stimuli in Foertsch and Gernsbacher's (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) Experiment 1. This raises the possibility that the differences between the results in Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) and Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007) are due not just to different methodology and antecedent type manipulation, but to differences between the effect that quantificational and referential antecedents may have on processing they. Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) did not directly compare referential and quantificational antecedents,Footnote 6 nor is it guaranteed that all the indefinites in their stimuli are quantificational, or unambiguously interpreted as such by participants.Footnote 7 Since Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007) did not test quantificational antecedents, we do not know whether their finding of a cost for they, using finer-grained methodologies than whole sentence reading time, would extend to quantificational and gendered antecedents.

In summary, the processing literature shows that, at least among the English speakers tested, non-gendered antecedents for singular they are more acceptable than gendered antecedents (Doherty and Conklin Reference Doherty and Conklin2017) and that non-gendered antecedents confer upon singular they a processing advantage (Foertsch and Gernsbacher Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997, Doherty and Conklin Reference Doherty and Conklin2017). The suggestive evidence in Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) is that these gender and bound-variable properties interact, such that a gendered antecedent has deleterious effects for referential but not for bound-variable singular they.

Stepping back, our goal is first, to determine whether this expectation is empirically borne out. Two offline experiments verify the intuitions reported in the syntax-semantics literature about the high acceptability of bound singular they with both gendered and non-gendered antecedents, in contrast to referential singular they. The self-paced reading experiments (one with non-gendered antecedents, the other with gendered antecedents) then sought to identify whether gender imposes processing difficulty differently for referential vs. bound singular they.

2.4 Ensuring bound-variable interpretations

Before turning to the experiments, it is important that we identify how our studies avoid the confounds posed by using an indefinite noun phrase antecedent as was done in the studies documented above. We chose instead to use the universal quantifier every in our studies, which is morphosyntactically singular. Universals like every are not without complications, since they can indirectly introduce a plural referent – often called the reference set or witness set (Nouwen Reference Nouwen2003, Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Filik and Moxey2009). They can take this plurality as its referent:

(8) Every person in the room said they were gathered for a nice meal.

They must denote a plurality in (8) since it serves as the argument of the predicate gather, which requires a plural subject (#The person gathered for a nice meal). Witness-set readings are hard to block. One strategy, following Rullmann (Reference Rullmann2003), involves contexts that force uniqueness at the level of atoms on the pronoun, as in (9).

(9) Everyone thinks that they are the smartest person in the world.

If they referred to the witness set (the set of people that form the restrictor of the quantifier), then (9) would attribute to each person the belief that all people are the smartest. This is not a felicitous interpretation for (9), and we take it that readers do not pursue such an analysis.

Our experimental stimuli were constructed along these lines in order to force a truly bound singular reading and to block a witness-set reading. For each trial we provide a context sentence that sets up the expectation that the relevant pronoun must refer to a singular atomic individual: in (10), we learn that only one person can win the race. The target sentence (10a), which contains the quantifier and the bound variable, also reinforces the singularity of the pronoun with a singular-enforcing definite description ‘the winner’ in advance of the critical pronoun with which it is identified in a copular relation. The critical pronoun is placed in a post-copula position in a specificational clause. The singular definite description in the pre-copula position (the winner in (10a)) is the inverse predicate (Heycock Reference Heycock1992, Moro Reference Moro1997, den Dikken Reference den Dikken2006) and forces the post-copula pronoun to be interpreted as singular.

(10) Context sentence: Only one runner could win the race.

a. Target sentence: Every runner thought that the winner would be them/him.

b. Target sentence: The tallest runner hoped that the winner would be them/him.

In the experiments we report below, we compare referential DPs (such as the tallest runner) as in (10b) to quantificational DPs as in (10a) anteceding them; in each case, we use a morphologically singular pronoun (him) as the baseline. Note that in the target sentence (10b), the referential antecedent the tallest runner contains the superlative adjective tallest, which makes it not minimally different from the quantificational antecedent every runner in (10a). This modification was necessary in order to facilitate a successful reference. A unique referent of the runner without the superlative modifier is not identifiable, as the given context implies that there is more than one runner.Footnote 8

We present results of both acceptability rating and self-paced reading experiments. The first experiment group (Experiment 1ab) uses non-gendered antecedents (e.g., runner). The second experiment group (Experiment 2ab) examines gendered antecedents (e.g., granddaughter).

3. Experiments 1

Experiment 1a tested the acceptability of singular they with non-gendered universally quantified phrases in comparison to non-gendered referential noun phrases. Experiment 1b tested the processing profile of singular they with these same two types of antecedents in a self-paced reading (SPR) study. We expected to verify that with truly quantificational antecedents bound singular they is more acceptable. If the ambiguity hypothesis holds we expect bound singular they to exhibit a processing advantage over referential singular they. Furthermore, given that previous literature found that singular they with non-gendered antecedents shows improved acceptability and faster processing times compared to gendered antecedents, any degradation in acceptability or difficulty in processing would be most naturally attributable to a sensitivity to number marking, that is, that they is less congruent with singular antecedents than he/she.

3.1 Experiment 1a

If singular they is sensitive to the grammatical number of the antecedent, then we should find sentences containing them with singular non-gendered antecedents to be less acceptable than sentences containing him with singular non-gendered antecedents. Moreover, if the number on the antecedent has a different effect in the acceptability of singular bound-variable them and singular referential them, then we should find an interaction between antecedent type (quantificational vs. referential) and pronoun type (them vs. him).

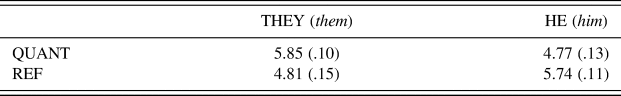

3.1.1 Materials

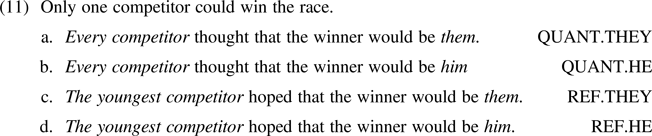

Twenty test item sets were constructed as in (11), where a non-gendered universal quantifier subject (QUANT) or a non-gendered referential subject (REF) appeared with a singular gendered pronoun him (HE) or them (THEY).Footnote 9 These subjects are intended to serve as the antecedent of the pronoun in each target sentence, and were all independently rated as being associated with low gender stereotypicality in Doherty and Conklin (Reference Doherty and Conklin2017). Each item set was thus created crossing two two-level factors, Antecedent (QUANT vs. REF) and Pronoun (THEY vs. HE). Each target sentence was presented with a context sentence as in (11) to further ensure that the relevant pronoun referred to a singular entity.Footnote 10

Thirty filler items such as (12) were also included. Each filler item was composed of two sentences: the first sentence contained a gender-stereotyped proper name and an expression such as alone to promote a coreferential interpretation for the subsequent pronoun; the second sentence contained they or a singular pronoun that matched the gender of the proper name.

(12)

a. Bob was coloring alone in the classroom. While choosing a crayon, he refused to pick a bright color.

b. Richard was sleeping alone in the bedroom. After waking up, they refused to make some breakfast.

It has been observed in the literature that for some English users (e.g., Stage 1 and 2 in Konnelly and Cowper's Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020 work) they cannot generally be used to refer to gendered singular proper nouns. In an experimental setting, Ackerman et al. (Reference Ackerman, Riches and Wallenberg2018) found they with gender-biased names to be distinctly marked (at least for some participants) when paired with referential they. We thus expect that our fillers with they will be rated much less acceptable than the ones with singular gendered pronouns.

3.1.2 Participants and Procedures

Thirty-six native English users were recruited online using Amazon Mechanical Turk and directed to the experiment on Ibex Farm (Drummond Reference Drummond2013). The age of the participants ranged from 24 to 65, with the mean age at 38. Participants self-reported to be native users of English by answering a survey question at the end of the experiment. Each participant received $1.50 as compensation for participation upon completion of the experiment.

The test items were distributed over four lists in a Latin-square design so that no participant saw any one item in more than one condition, but all filler items were seen by all participants. Each list contained 20 test items and 30 fillers which were displayed in a randomized order. Participants rated the acceptability of each target sentence from 1 (not acceptable) to 7 (acceptable).

3.1.3 Results

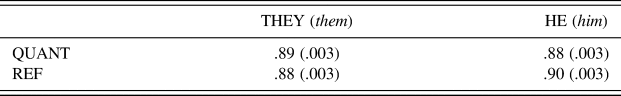

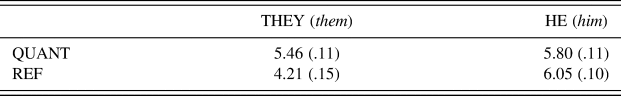

The mean ratings and standard errors by condition are provided in Table 1. Also, the distributions of mean ratings of participants and the mean ratings across participants by condition are shown in Figure 1. Each hollow dot represents a mean rating of a participant in a given condition, and each solid dot represents the mean rating across participants in a given condition.

Figure 1: Distributions of mean ratings of participants (hollow dots), and mean ratings across participants with standard errors (solid dots), Experiment 1a

Table 1: Mean ratings by condition (SE), Experiment 1a

We analyzed the ratings by means of a linear mixed-effects model in R (R Development Core Team, 2020). The lme4 package was used to fit the model (Bates Reference Bates2005), and the lmerTest package was used to obtain ![]() $p$-values (Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova and Brockho2014). In analyses of data obtained from all experiments reported in this paper, we first attempted to fit a maximal random-effects structure with random intercepts and random slopes for participants and items (Barr et al. Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). If that model did not converge, we fit a model just like the maximal model, but with the random correlation parameter for the interaction term removed for both participants and items. Moreover, the predictors in all analyses reported here were sum coded, with one of the levels coded as 1, and the other as –1.Footnote 11

$p$-values (Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova and Brockho2014). In analyses of data obtained from all experiments reported in this paper, we first attempted to fit a maximal random-effects structure with random intercepts and random slopes for participants and items (Barr et al. Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). If that model did not converge, we fit a model just like the maximal model, but with the random correlation parameter for the interaction term removed for both participants and items. Moreover, the predictors in all analyses reported here were sum coded, with one of the levels coded as 1, and the other as –1.Footnote 11

We fit a mixed model to the ratings with fixed factors of Antecedent (QUANT vs. REF) and Pronoun (THEY vs. HE).Footnote 12 We found an interaction between the two factors (Est = 0.51, ![]() $SE$ = 0.10,

$SE$ = 0.10, ![]() $t$ = 4.95,

$t$ = 4.95, ![]() $p$ < 0.001). We conducted planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment, and compared the ratings on the THEY sentences and the HE sentences in the two Antecedent conditions. According to the planned comparisons, this interaction was due to the fact that the THEY condition had higher ratings than the HE condition in sentences with quantified antecedents (by-participant:

$p$ < 0.001). We conducted planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment, and compared the ratings on the THEY sentences and the HE sentences in the two Antecedent conditions. According to the planned comparisons, this interaction was due to the fact that the THEY condition had higher ratings than the HE condition in sentences with quantified antecedents (by-participant: ![]() $p$ < 0.01, by-item:

$p$ < 0.01, by-item: ![]() $p$ < 0.001), while the reverse was the case in sentences with referential antecedents (by-participant:

$p$ < 0.001), while the reverse was the case in sentences with referential antecedents (by-participant: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 0.01, by-item:

$ = $ 0.01, by-item: ![]() $p$ < 0.001).

$p$ < 0.001).

3.1.4 Discussion

Our participants rated they sentences with non-gendered quantified antecedent phrases much higher than the ones with non-gendered referential antecedent phrases. This result indicates that our participants accepted them as a bound-variable pronoun anteceded by a non-gendered, universally quantified phrase. Participants in fact preferred them to the gendered, singular him as a bound variable. In contrast, singular gendered pronouns were preferred to them as referential pronouns. Note however that referential singular them was by no means unacceptable to our participants. Even though the sentences with referential singular they were rated lower than the ones with referential singular gendered pronouns, they were rated relatively high (4.80), as high as the sentences with bound singular gendered pronouns (4.77), which is a grammatically possible option.

Comparing the distribution of ratings in the THEY conditions (indicated with hollow dots in Figure 1), while only two participants had mean ratings below 4 in the QUANT.THEY condition, nine participants had mean ratings below 4 in the REF.THEY condition. Thus, more inter-speaker variation is attested in the REF.THEY condition. This finding is consistent with what is reported in Conrod (Reference Conrod2019) and Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020) that speakers range from those who reject the use of referential singular they to those who have absolutely no problem with it. Further, upon closer inspection of the data, two participants who had mean ratings below 4 in the REF.THEY condition also had mean ratings below 4 in the QUANT.THEY condition, and seven participants who had mean ratings below 4 in the REF.THEY condition had mean ratings above 4 in the QUANT.THEY condition. Thus, these participants who found singular they to be degraded with a referential antecedent found it to be more acceptable with a quantificational antecedent.

The validity of these results is supported by those of the filler sentences. The sentence pairs with they were rated much lower (2.95) than the ones with gender-matched singular pronouns (6.42). As with the they sentences with referential antecedents, there was variation in the acceptability of they sentences with proper-name antecedents among the participants, ranging from those who had very low mean acceptability ratings to those who had very high mean acceptability ratings. But more participants rated the they sentences with proper name antecedents below 4 (N=27), in comparison to the they sentences with non-gendered referential antecedents (N=9). While some participants who rated the non-gendered referential they sentences high also rated the proper name they sentences high, many did not. These results confirm the intuition and findings reported in the extant literature that while some users find proper name they sentences perfectly acceptable (Conrod Reference Conrod2019, Konnelly and Cowper Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020), for many users, singular they anteceded by gendered proper nouns is less acceptable than with referential DPs (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2017, Ackerman et al. Reference Ackerman, Riches and Wallenberg2018).

3.2 Experiment 1b

Since Experiment 1a showed that with non-gendered antecedents, referential and bound singular they were acceptable at different rates, we asked whether this difference appeared in online processing. The expectation is that referential singular they will show elevated reading times compared to bound-variable singular they (when measured against the baseline him). We should thus find an interaction between antecedent type (quantificational vs. referential) and pronoun type (them vs. him).

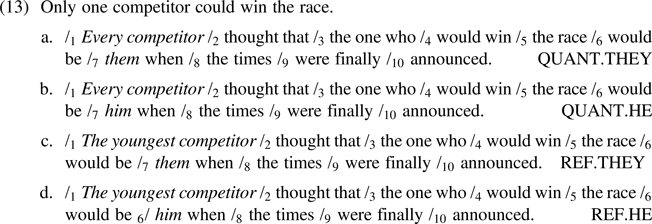

3.2.1 Materials

The materials were similar to the ones used in Experiment 1a, crossing two two-level factors, Antecedent (QUANT vs. REF) and Pronoun (THEY vs. HE), yielding four experimental conditions. The test sentences in Experiment 1b, however, were made to be longer so that the sentences do not end with the target region containing the critical pronoun. Also, the definite description in the embedded specificational clause began with the one who to ensure a singular interpretation of the post-copula pronoun. Excluding the context sentences, the target sentences were divided into ten regions, with region 1 containing the antecedent and region 7, the target region, containing the critical pronoun, as illustrated (13).Footnote 13

3.2.2 Participants and Procedures

194 native English users, who did not participate in Experiment 1a, were recruited online using Amazon Mechanical Turk and directed to the experiment on Ibex Farm. The age of the participants ranged from 20 to 74, with the mean age at 40. Participants self-reported to be native users of English by answering a survey question at the end of the experiment. Each participant received $1.50 as compensation upon completion of the experiment.

Twenty item sets like (13) were distributed over four lists in a Latin-square design. In addition, each list contained a set of 40 fillers. The sentences were presented on Ibex Farm in a uniquely generated random order for each participant, using the moving-window paradigm (Just et al. Reference Just, Carpenter and Woolley1982). After reading the context sentence, participants advanced to the next region by pressing on the space bar. No region could be displayed more than once. After each experimental sentence was read, a comprehension question was presented, which could be answered by pressing one key for ‘yes’ or another key for ‘no’. The comprehension questions tested participants’ understanding of the sentence, but not their interpretation of the critical pronoun. The comprehension question for the item in (13) is in (14).

(14) Was there going to be a winner of a race?

3.2.3 Results

Participants with low comprehension question response score (<50%) and extremely fast reading speed per region (<50ms) were excluded. This resulted in eliminating one participant from analysis due to a low comprehension question response score (36%), leaving 193 participants. Further, using the trimr package (Grange Reference Grange2015), reading times of a region that were 10 standard deviations above the mean were removed, in order to exclude extreme outliers from analysis. Altogether, this resulted in removing 0.5% of the observations from the data.

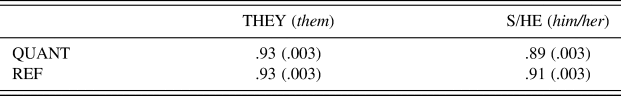

The grand mean comprehension question response score on test sentences was 89%. The mean proportions of correct responses for the comprehension questions are reported in Table 2. The comprehension questions tested participants’ attention to the overall sentence content, and the results show no impact of the manipulated factors on comprehension generally.

Table 2: Proportion of Correct Responses (SE), Experiment 1b

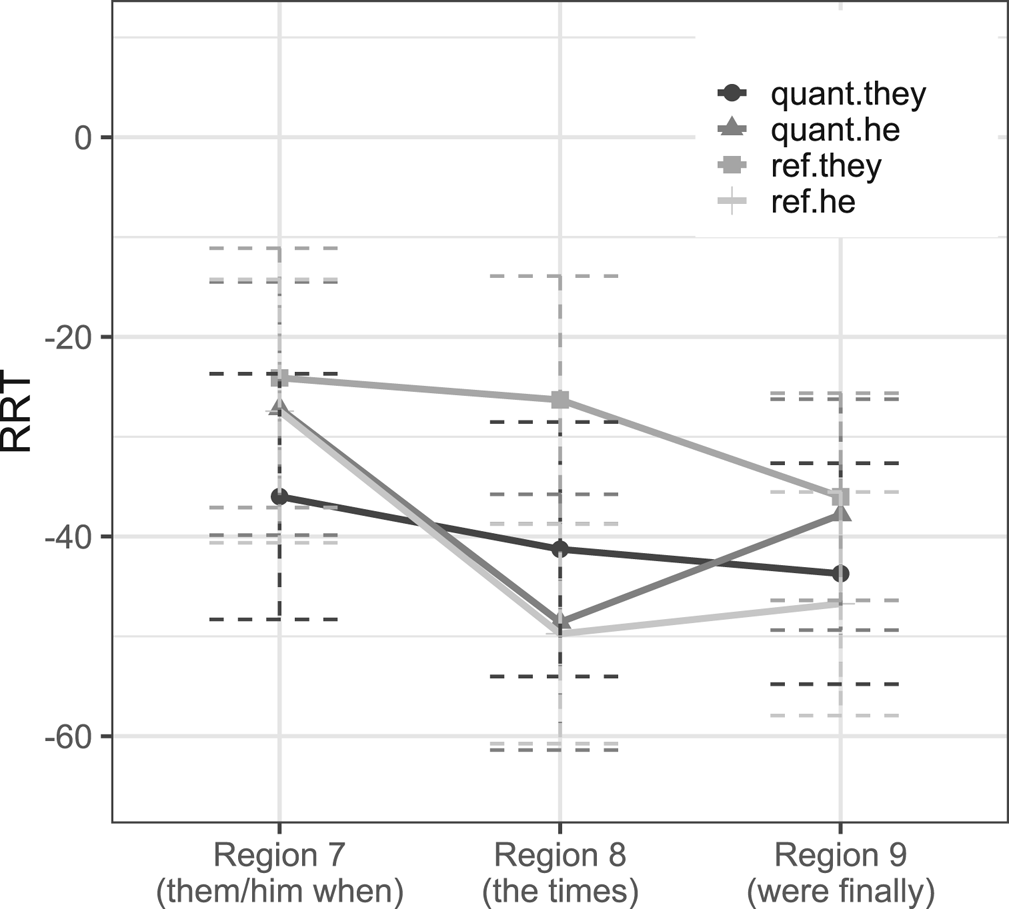

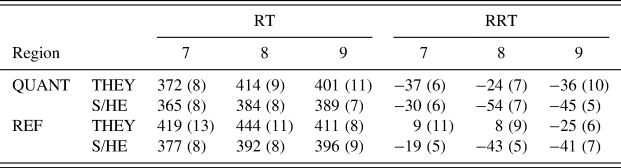

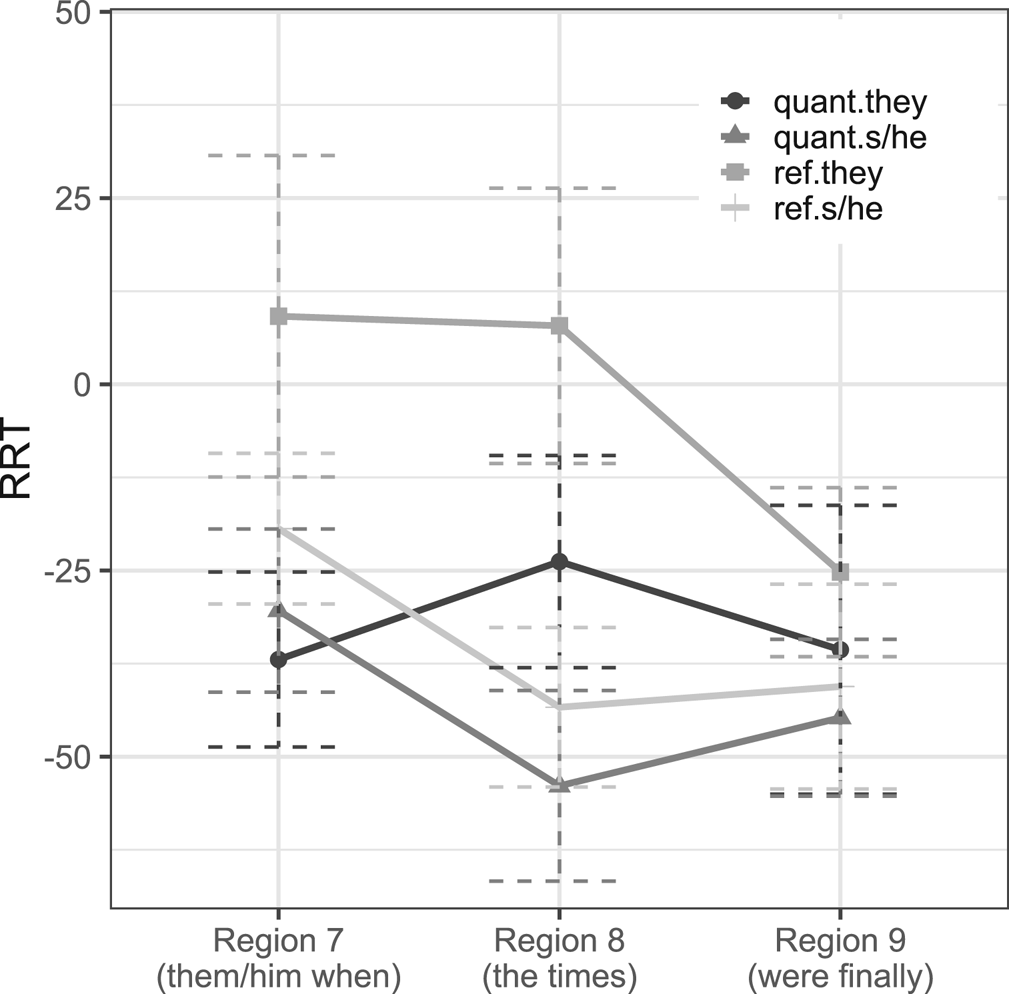

Mean raw reading times and mean residual reading times (RRTs) by condition for the regions of analysis are reported in Table 3. These represent reading times for all data, regardless of whether the comprehension question was answered correctly. The regions of analysis are Region 7 (the target region), Region 8 (the spillover region), and Region 9. We calculated RRTs using character length from the entire dataset (including fillers) to estimate the reading time for each region for each participant (Ferreira and Clifton Reference Ferreira and Clifton1986, Trueswell and Tanenhaus Reference Trueswell and Tanenhaus1994, Phillips Reference Phillips2006). The graph in Figure 2 summarizes mean RRTs by condition for the regions of analysis.

Figure 2. Mean RRTs and standard errors for the regions of analysis, Experiment 1b

Table 3: Mean Raw Reading Times (SE) and Mean RRTs (SE) in ms, Experiment 1b

We analyzed each region's RRTs with a mixed model, with a random-effects structure as described for Experiment 1a.Footnote 14

In analyzing the RRTs of region 7 (target region), we found no main effect or interaction. In region 8 (spillover region), the analysis showed a main effect of Pronoun (Est = 7.62, ![]() $SE$ = 3.25,

$SE$ = 3.25, ![]() $t$ = 2.34,

$t$ = 2.34, ![]() $p$ < 0.05), such that overall the THEY condition showed slower reading times than the HE condition. In region 9, the analysis did not reveal any effect.

$p$ < 0.05), such that overall the THEY condition showed slower reading times than the HE condition. In region 9, the analysis did not reveal any effect.

3.2.4 Discussion

Bound-variable and referential singular they did not differ in reading time measures, contrary to the differences found in acceptability. Moreover, bound singular they, like referential they, incurs a processing cost in the spillover region, revealed by the main effect of Pronoun that persisted across REF and QUANT conditions. This finding is important for several reasons. First, recall that Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) did not find slower reading times for sentences containing singular they and non-gendered referential antecedents. Their finding was called into question on methodological grounds by Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007), who showed that a finer-grained measure of processing difficulty – eye-tracking – does reveal a processing cost for singular they with non-gendered referential antecedents. As pointed out by a reviewer, the two studies are asking different questions. Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) are investigating gender processing, while Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007) are investigating number processing. The main conclusions of the two studies are therefore not necessarily mutually incompatible. Nonetheless, the results of our Experiment 1b show that self-paced reading is, like eye-tracking, sensitive enough to detect a processing cost. Second, these results demonstrate that even though bound singular they is preferred in offline judgments to he/him with non-gendered antecedents, it nonetheless poses a processing cost, one that appears to be overcome in reflective judgments without entailing reduced acceptability. But bound they and referential they have the same processing profile here. This does not bear out predictions we derived from the ambiguity hypothesis; namely, that the linguistically simpler bound they would be accessed first and pose no processing problems upon retrieving a quantified antecedent, while retrieving a referential antecedent might require re-analyzing the pronoun as referential. We return to the significance of the absence of such a finding in section 5.

4. Experiments 2

Experiment 2a investigated the acceptability of singular they with gendered quantificational and referential antecedents. As noted in footnote Footnote 2, by gendered we mean both nouns like grandson and woman and gender-stereotyped nouns like nurse and surgeon. As with Experiment 1a, Experiment 2a was an acceptability rating study, to confirm intuitions reported in the literature that gendered antecedents do not reduce the acceptability of bound singular they to the same extent, if at all, as they do for referential singular they. Experiment 2b was designed to compare the processing profile of singular they with quantified and referential gendered antecedents. The previous literature found that gendered antecedents generally reduce the processing ease of referential singular they (Foertsch and Gernsbacher Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997, Doherty and Conklin Reference Doherty and Conklin2017, Ackerman Reference Ackerman2018, Ackerman et al. Reference Ackerman, Riches and Wallenberg2018). Building on Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997), however, we expect that bound-variable singular they will not show this same sensitivity to gender, and will be read with less difficulty than referential singular they.

4.1 Experiment 2a

If the gender of the antecedent plays a role in the acceptability of singular they, then we should find sentences containing them with singular gendered antecedents to be less acceptable than sentences containing him/her with the same type of gendered antecedents. Moreover, if a gendered antecedent has a different effect in the acceptability of singular bound-variable them and singular referential them, then we should find an interaction between antecedent type (quantificational vs. referential) and pronoun type (them vs. him/her).

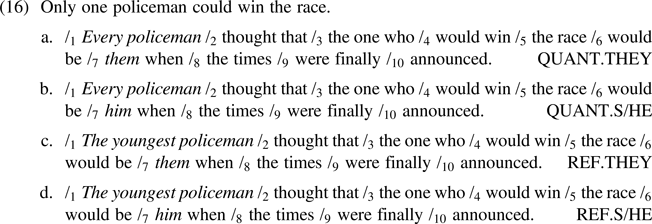

4.1.1 Materials

Twenty test items similar in form to the materials used in Experiment 1a were constructed as in (15). Like the items in Experiment 1a, the antecedent phrases were either quantified (QUANT) or referential (REF). In all cases, the nouns were gendered.Footnote 15 Half of the stimuli use antecedents associated with female gendered individuals and the other half with male gendered individuals. The pronoun was either them or whichever singular pronoun (him/her) was appropriate to the gender of the antecedent.

In addition, 30 filler items were included which were used in Experiment 1a.

4.1.2 Participants and Procedures

Thirty-seven native English users, who did not participate in Experiments 1a or 1b, completed the experiment online, receiving $1.50 for compensation. They were recruited using Amazon Mechanical Turk and redirected to the experiment on Ibex Farm. The age of the participants ranged from 23 to 59, with the mean age at 37. Participants self-reported to be native users of English by answering a survey question at the end of the experiment.

Twenty item sets as in (15) were distributed over four lists in a Latin-square design. In addition, each list contained the same set of 30 fillers.

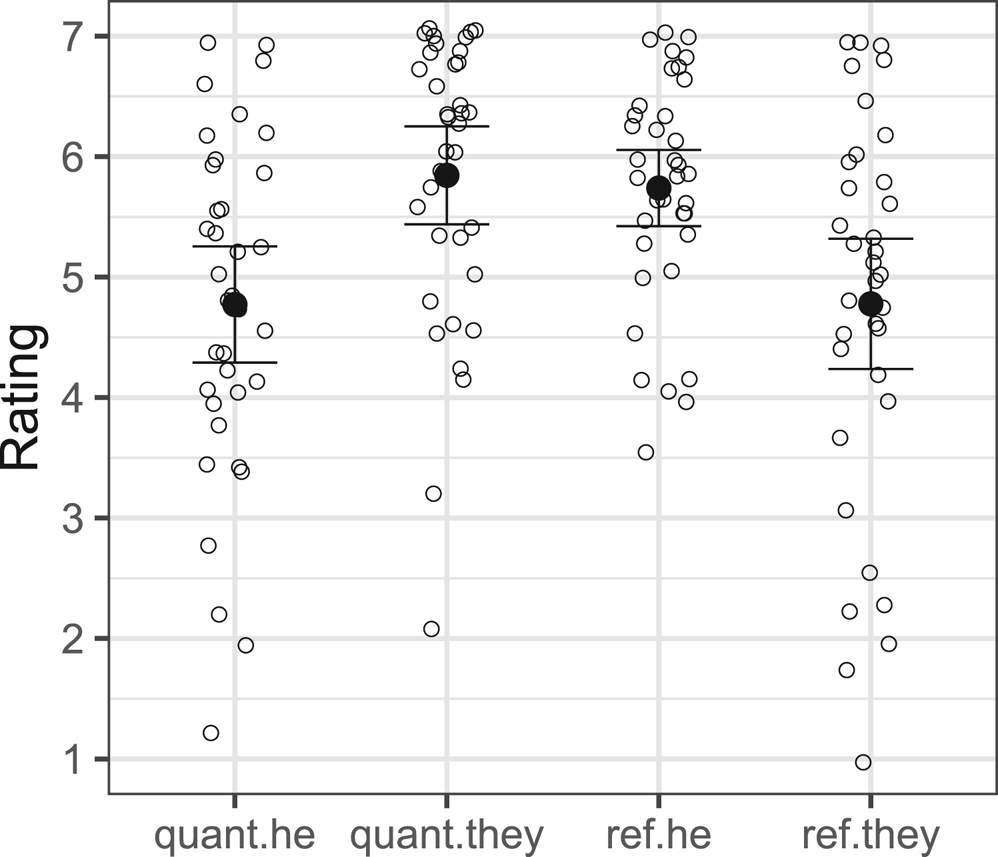

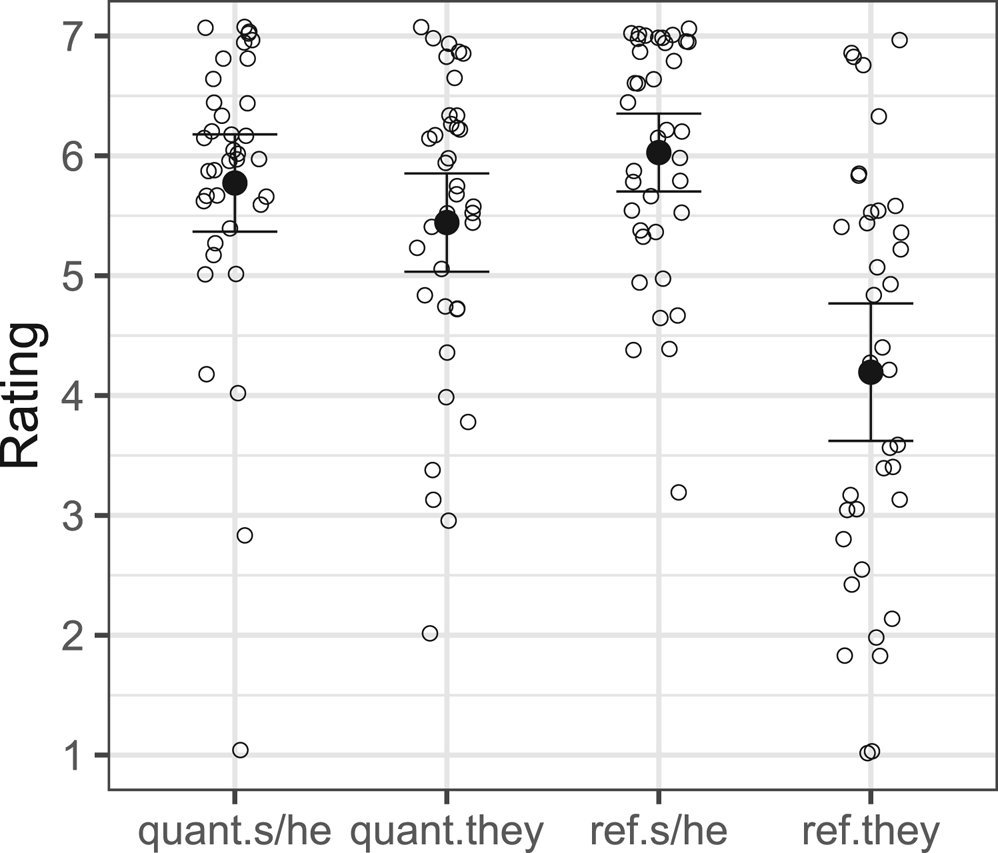

4.1.3 Results

The mean ratings and standard errors by condition are provided in Table 4. The distributions of mean ratings of participants and the mean ratings across participants by condition are shown in Figure 3. Each hollow dot represents a mean rating of a participant in a given condition, and each solid dot represents the mean rating across participants in a given condition.

Figure 3. Distributions of mean ratings of participants (hollow dots), and mean ratings across participants with standard errors (solid dots), Experiment 2a

Table 4: Mean ratings by condition (SE), Experiment 1b

We analyzed the mean ratings with a mixed model, with a random-effects structure as described for Experiment 1a.Footnote 16 We found a main effect of Pronoun (Est = −0.54, ![]() $SE$ = 0.10,

$SE$ = 0.10, ![]() $t$ = −5.37,

$t$ = −5.37, ![]() $p$ < 0.001) and a main effect of Antecedent (Est = 0.23,

$p$ < 0.001) and a main effect of Antecedent (Est = 0.23, ![]() $SE$ = 0.06,

$SE$ = 0.06, ![]() $t$ = 3.92,

$t$ = 3.92, ![]() $p$ < 0.001), such that overall the sentences with him/her (mean rating: 5.93) were rated higher than the ones with them (mean rating: 4.84), and the sentences with quantified antecedent phrases (mean rating: 5.63) were rated higher than the ones with referential antecedent phrases (mean rating: 5.13). Crucially, we found an interaction between the two factors (Est = 0.37,

$p$ < 0.001), such that overall the sentences with him/her (mean rating: 5.93) were rated higher than the ones with them (mean rating: 4.84), and the sentences with quantified antecedent phrases (mean rating: 5.63) were rated higher than the ones with referential antecedent phrases (mean rating: 5.13). Crucially, we found an interaction between the two factors (Est = 0.37, ![]() $SE$ = 0.05,

$SE$ = 0.05, ![]() $t$ = 7.70,

$t$ = 7.70, ![]() $p$ < 0.001). Planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment revealed that this interaction was due to the fact that for sentences in the REF condition, the them sentences were rated lower than the ones with singular gendered pronoun (by-participant:

$p$ < 0.001). Planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment revealed that this interaction was due to the fact that for sentences in the REF condition, the them sentences were rated lower than the ones with singular gendered pronoun (by-participant: ![]() $p$ < 0.001, by-item:

$p$ < 0.001, by-item: ![]() $p$ < 0.001), while in the QUANT condition, sentences with them were rated as high as the ones with a singular gendered pronoun (by-participant:

$p$ < 0.001), while in the QUANT condition, sentences with them were rated as high as the ones with a singular gendered pronoun (by-participant: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 1.00, by-item:

$ = $ 1.00, by-item: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 0.79).

$ = $ 0.79).

4.1.4 Discussion

The results of Experiment 2a are similar to those of Experiment 1a. The participants rated them sentences with gendered quantified antecedent phrases much higher than the ones with gendered referential antecedent phrases. Participants also rated sentences with singular gendered pronouns much higher than the ones with them in the REF condition. One notable difference, however, is that with gendered quantified antecedents, sentences with singular gendered pronouns were rated just as high as the ones with them, whereas they were rated lower than the sentences with them in Experiment 1a. Another difference is that the them sentences with referential antecedents in Experiment 2a (4.21) are numerically rated lower than the ones in Experiment 1a (4.81). We interpret this as a cumulative effect of number and gender on the acceptability of referential singular them: neither the number nor the gender of the antecedent is expressed by the pronoun. These results taken together suggest that gender plays a role only in the acceptability of referential singular they as expected, but it plays a different role for bound-variable singular they.

Comparing the distribution of ratings in the THEY conditions (indicated with hollow dots in Figure 3), five participants had mean ratings below 4 in the QUANT.THEY condition, and 17 participants had mean ratings below 4 in the REF.THEY condition. Thus, as in Experiment 1a, more inter-speaker variation is attested in the REF.THEY condition than in the QUANT.THEY condition in Experiment 2a, with speakers ranging from those who reject the use of referential singular they to those who accept it (Conrod Reference Conrod2019, Konnelly and Cowper Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020). Further, upon closer inspection of the data, while the same five participants had mean ratings below 4 in both the REF.THEY and the QUANT.THEY condition, 13 participants who had mean ratings below 4 in the REF.THEY condition had mean ratings above 4 in the QUANT.THEY condition. Thus, as with the results in Experiment 1a, many participants in Experiment 2a who found singular they to be degraded with a referential antecedent found it to be more acceptable with a quantificational antecedent.

The results for filler items were similar to Experiment 1a. The sentence pairs with they were rated much lower (3.69) than the ones with gender-matched singular pronouns (6.39). Looking at the they sentences more closely, there was a variation in the acceptability among the participants, with 15 participants having mean ratings above 4, and 22 participants below 4. As in Experiment 1a, while some participants who rated the gendered referential they sentences high also rated the proper-name they sentences high, many participants rated the proper-name they sentences lower than the gendered referential they sentences, resulting in lower mean rating for the proper-name they sentences (3.69) than the gendered referential they sentences (4.21). As in Experiment 1a, the filler results in Experiment 2a confirm the intuition and findings reported in the extant literature that for many speakers, singular they anteceded by gendered proper nouns is less acceptable than referential DPs (Bjorkman Reference Bjorkman2017, Ackerman et al. Reference Ackerman, Riches and Wallenberg2018), and at the same time, there are speakers who find no problem at all with proper-name they sentences (Conrod Reference Conrod2019, Konnelly and Cowper Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020).

4.2 Experiment 2b

While the offline acceptability of bound singular they with a gendered quantifier antecedent was high, particularly compared to referential they, the question arises whether this leads to any processing differences. If the gender of the antecedent plays a role in the processing of singular they, then we should find they/them with singular gendered antecedents to be more difficult to process (increase in reading time) than him/her with singular gendered antecedents. Moreover, if the gender of the antecedent has different effects on the processing of singular bound-variable them versus singular referential them, then we should find an interaction between antecedent type (quantificational vs. referential) and pronoun type (them vs. him/her).

4.2.1 Materials, Participants and Procedures

The materials were similar to the ones used in Experiment 1b, except that the antecedent noun phrases were gendered, as in (16). Just as in Experiment 1b, each item set represented four conditions, crossing two two-level factors, Antecedent (QUANT vs. REF) and Pronoun (THEY vs. S/HE).

Twenty item sets like (16) were created and distributed over four lists in a Latin-square design. In addition, each list contained a set of 40 fillers that were used in Experiment 1b. The sentences were presented in Ibex Farm, following the same procedure as Experiment 1b. 168 native English users, who did not participate in Experiments 1a, 1b, or 2a, were recruited online using Amazon Mechanical Turk and directed to the experiment on Ibex Farm. The age of the participants ranged from 25 to 72, with the mean age at 43. Each participant received $1.50 as compensation upon completion of the experiment.

4.2.2 Results

Just as in Experiment 1b, participants with low comprehension question response score (<50%) and extremely fast reading speed per region (<50ms) were excluded. This resulted in eliminating two participants: one was due to low comprehension question response score (47%) and another was due to extremely fast average reading speed per region (47ms). This left 166 participants for analysis. Reading times that were 10 standard deviations above the mean were also removed. This resulted in removing 1.2% of the observations from the data for analysis.

The grand mean comprehension-question response score on test sentences was 91%. The mean proportions of correct responses for the comprehension questions of the test items are given in Table 5.

Table 5: Proportion of Correct Responses (SE), Experiment 2b

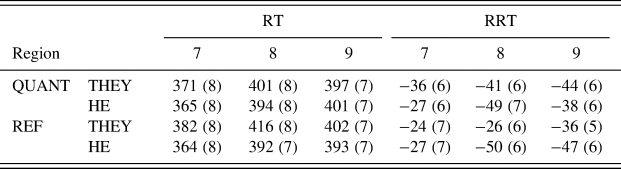

Mean raw reading times and mean RRTs by condition for the regions of analysis are reported in Table 6. These represent reading times for all data, whether the comprehension question was answered correctly or not.

Table 6: Mean Raw Reading Times (SE) and Mean RRTs (SE) in ms, Experiment 2b

The graph in Figure 4 summarizes mean RRTs by condition for the regions of analysis for all data.

Figure 4. Mean RRTs and standard errors for the regions of analysis, Experiment 2b

As in the analysis performed in Experiment 1b, here we analyzed each region's RRTs with a mixed model, with a random-effects structure as described for Experiment 1a.Footnote 17

In region 7 (target region), the analysis revealed a main effect of Antecedent (Est = −14.70, ![]() $SE$ = 4.41,

$SE$ = 4.41, ![]() $t$ = −3.34,

$t$ = −3.34, ![]() $p$ < 0.01) such that overall the sentences with quantificational antecedents (mean RRT: -34 ms, mean raw RT: 369 ms) had faster reading times than the ones with referential antecedents (mean RRT: -5 ms, mean raw RT: 398 ms). The analysis also revealed an interaction between Antecedent and Pronoun (Est = −9.06,

$p$ < 0.01) such that overall the sentences with quantificational antecedents (mean RRT: -34 ms, mean raw RT: 369 ms) had faster reading times than the ones with referential antecedents (mean RRT: -5 ms, mean raw RT: 398 ms). The analysis also revealed an interaction between Antecedent and Pronoun (Est = −9.06, ![]() $SE$ = 4.46,

$SE$ = 4.46, ![]() $t$ = −2.03,

$t$ = −2.03, ![]() $p$ < 0.05). According to the results of planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment, the interaction is due to the THEY condition having longer reading time than the S/HE condition with a referential antecedent (by-participant:

$p$ < 0.05). According to the results of planned comparisons using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment, the interaction is due to the THEY condition having longer reading time than the S/HE condition with a referential antecedent (by-participant: ![]() $p$ < 0.05, by-item:

$p$ < 0.05, by-item: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 0.05). In contrast, the two pronoun conditions showed similar reading times with a quantificational antecedent (by-participant:

$ = $ 0.05). In contrast, the two pronoun conditions showed similar reading times with a quantificational antecedent (by-participant: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 1.00, by-item:

$ = $ 1.00, by-item: ![]() $p$

$p$ ![]() $ = $ 1.00).

$ = $ 1.00).

In the analysis of RRTs in region 8 (spillover region), we found a main effect of Antecedent (Est = −9.66, ![]() $SE$ = 3.65,

$SE$ = 3.65, ![]() $t$ = −2.65,

$t$ = −2.65, ![]() $p$ < 0.01) and a main effect of Pronoun (Est = 20.39,

$p$ < 0.01) and a main effect of Pronoun (Est = 20.39, ![]() $SE$ = 4.39,

$SE$ = 4.39, ![]() $t$ = 4.65,

$t$ = 4.65, ![]() $p$ < 0.001). Overall, the referential condition (mean RRT: −18 ms, mean raw RT: 418 ms) had a longer reading time than the quantificational condition (mean RRT: −39, mean raw RT: 399 ms), and the THEY condition (mean RRT: −8 ms, mean raw RT: 429 ms) had a longer reading time than the S/HE condition (mean RRT: −49, mean raw RT: 388 ms). The analysis in region 9 did not reveal any effect.

$p$ < 0.001). Overall, the referential condition (mean RRT: −18 ms, mean raw RT: 418 ms) had a longer reading time than the quantificational condition (mean RRT: −39, mean raw RT: 399 ms), and the THEY condition (mean RRT: −8 ms, mean raw RT: 429 ms) had a longer reading time than the S/HE condition (mean RRT: −49, mean raw RT: 388 ms). The analysis in region 9 did not reveal any effect.

4.2.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 2b reveal a difference between quantificational and referential antecedents: with gendered antecedents referential singular they exhibits a processing difficulty in comparison to him/her, while bound singular they is processed just as easily as the singular gendered pronoun in the target region. This is the gender-quantifier interaction, presaged in the studies by Foertsch and Gernsbacher (Reference Foertsch and Gernsbacher1997) and Ackerman (Reference Ackerman2018). In the general discussion we turn to how to account for the differential sensitivity to gender by bound versus referential they, right at the point of encountering the pronoun.

In addition to the differences between bound and referential they, there was still a residual processing cost for both bound and referential singular they compared to the singular gendered pronouns. At the spillover region there was a main effect that penalized they across the board. Note that the same main effect of Pronoun was found in the spillover region of Experiment 1b with non-gendered antecedents. What we are seeing, then, is that even the highly acceptable bound singular they can exhibit a small processing cost in comparison to a singular gendered pronoun. It is possible that this is due to a consistent, if weak and temporary, cost for singular antecedents for they/them. This is consistent with a theory in which they cues a search for a non-singular antecedent, as on the feature enrichment hypothesis; the retrieved antecedent mismatches in number, thus registering as a slowdown.

5. General discussion of experiments

In terms of processing difficulty, we found differences between quantificational and referential singular they only with gendered antecedents. Otherwise, singular they exhibited a slowdown in the spillover region with both quantified and referential antecedents, both gendered and non-gendered. The latter finding is not expected on the underspecification hypothesis we laid out in section 2.2, which suggests they would readily tolerate singular antecedents. Instead, it is in line with Sanford and Filik (Reference Sanford and Filik2007), who suggest that they launches a search for a non-singular antecedent. This is what the enrichment hypothesis predicts when applied to both bound and referential they. The across-the-board spillover effect is not compatible with the ambiguity hypothesis. The way we spelled out that hypothesis predicted that bound-variable they is both more readily accessed and does not trigger enrichment of number and gender features. We would not have expected bound singular they to pose any processing difficulties, especially with non-gendered antecedents, contrary to fact.

Where we found a bound–referential difference in processing was in interaction with gender. This suggests that there is indeed a processing advantage for bound over referential singular they but it cannot be a wholesale advantage. This is consonant with the expectations of the ambiguity hypothesis only as long as number and gender are distinguished. This would require number to be enriched on bound-variable they (causing a number clash) but not gender (avoiding a gender clash). In principle such representations could be constructed, given a highly articulated syntax with separate projections housing number and gender. Nonetheless, we think divergences between the offline and online results speak against such a move. This move would require that feature enrichment be defeasible so that while a ![]() $[ $-SG

$[ $-SG![]() $] $ enriched feature triggers a clash, in reflective judgment it could be cancelled on bound they, but not on referential they, and allow only bound they to be highly acceptable with a singular antecedent. Whether that is itself a plausible process, we do not know, but it leaves unanswered why

$] $ enriched feature triggers a clash, in reflective judgment it could be cancelled on bound they, but not on referential they, and allow only bound they to be highly acceptable with a singular antecedent. Whether that is itself a plausible process, we do not know, but it leaves unanswered why ![]() $[ $-SG

$[ $-SG![]() $] $ would be defeasible only on bound they.

$] $ would be defeasible only on bound they.

Even if the ambiguity hypothesis can be re-engineered to account for the differential interaction of number and gender with referential versus quantified antecedents, it suffers from a more general failure in light of the processing results of Experiment 1b. The ambiguity hypothesis more generally hinges on the assumption that readers will pursue a bound interpretation before a referential one, and upon retrieving a referential antecedent, would require re-analysis. There is no hint of this in Experiment 1b: that is, we found no additional cost for referential they compared to bound-variable they. So while the ambiguity account is successful in offering a place to locate the bound–referential distinction, it is not successful in accounting for either the offline or online results. To summarize with respect to the processing hypotheses: neither the underspecification hypothesis nor the ambiguity hypothesis were borne out; the enriched specification hypothesis was borne out for number. In section 6, we offer an alternative formal representation for bound vs. referential singular they that can capture the interaction between gender and quantification.

An interesting outcome of the studies was that the offline results were in alignment with the online results in some cases but not others. The online results for referential singular they were directly reflected by the offline results. In the acceptability judgment task, we found that referential singular they is less acceptable than referential singular gendered pronouns with both gendered and non-gendered antecedents. In both cases they was processed more slowly than he/she. The offline and online results for bound singular they were not in such neat alignment. For bound singular they, we found a processing delay with both gendered and non-gendered antecedents in the spillover region, just as with referential singular they. However, unlike referential singular they, we did not find any processing delay with either gendered or non-gendered antecedents for bound singular they at the pronoun region. In the offline acceptability judgment task, we found that bound singular they is just as acceptable as bound singular gendered pronouns with gendered antecedents. With non-gendered antecedents, it was even more acceptable than singular gendered pronouns. These findings suggest that while the antecedents’ number incurs processing cost for bound singular they, just as for referential singular they, the gender of the antecedent does not. Nonetheless, it appears that this difficulty incurred by the antecedents’ number is quickly overcome, as reflected by the offline results.

This kind of mismatch between online processing cost and offline acceptability can be found elsewhere in the literature: it has been shown that while singular gendered pronouns (he or she) that mismatch in gender with gender stereotyped antecedents (the nurse or the surgeon) incur processing difficulty, they do not result in degraded acceptability (Kreiner et al. Reference Kreiner, Sturt and Garrod2008). On the other hand, singular gendered pronouns that mismatch in gender with gendered antecedents (the policeman, the granddaughter) not only incur processing difficulty but also degrade acceptability. These findings suggest that the gender evoked by stereotype may be temporary, only affecting online processing, but the gender evoked by lexical properties of the antecedent persists, affecting both the online processing and the offline acceptability judgments. In a similar vein, the processing and acceptability mismatch of singular they that we found can be taken to mean that number is temporarily evoked in processing singular they as a bound variable, but the initial processing difficulty is overcome in reflective judgments.

In summary, results of the four studies confirm that bound-variable singular they enjoys an advantage over referential singular they, but not a wholesale one. Rather, the picture is nuanced. In processing, bound and referential singular they both show disadvantages compared to singular pronouns – which we took to be a type of number clash. Only with gendered antecedents did the bound-variable singular they offer a processing advantage, suggesting an interaction between gender and quantification. We detailed how the ambiguity hypothesis, which predicted advantages for bound over referential singular they, was not fully successful in accounting for the full pattern of outcomes. We end this article with a theoretical re-appraisal of the formal representation of bound vs. referential they, and test it against the offline and online results.

6. A theoretical re-appraisal

The ambiguity hypothesis placed the distinction between bound and referential singular they on the pronoun. An alternative, already suggested by Konnelly and Cowper (Reference Konnelly and Cowper2020), is that the locus of that difference is in the antecedent itself. We would like to put a version of this approach on the table. This version deploys representations that involve binder indices at the syntax-semantic interface in the style of Kratzer (Reference Kratzer2009) and Sudo (Reference Sudo2012, Reference Sudo2014).