In 2019, the world’s top 10 theme parks received 521.2 million visits. 1 Many feature ever taller and faster roller coasters with the current record holders “Kingda Ka” at Six Flags Great Adventure reaching 456 feet tall and “Formula Rossa” at Ferrari World Abu Dhabi achieving 149 miles per hour. 2 Previous case reports of injuries associated with roller coasters have predominantly focused on catastrophic injuries such as internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections with cerebral infarctions as well as subarachnoid hemorrhages, but have largely overlooked new or worsening headaches and dizziness not associated with devastating injury. Reference Rutsch, Niesen, Meckel and Reinhard3-Reference Leitao, Mendonca, Iyer and Kao5

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3) defines headache attributed to trauma or injury to the head and/or neck by a new headache occurring for the first time in close temporal relation to trauma or injury to the head and/or neck and when a preexisting headache with the characteristics of a primary headache disorder becomes chronic or is made significantly worse in close temporal relation to trauma or injury. 6 Post-traumatic headaches most commonly present with a migrainous phenotype in 88% of respondents according to one study, with 91% of patients developing new headaches in the absence of a previous headache disorder. Reference Ashina, Eigenbrodt and Seifert7 It is also notable that although chronification in migraine is a process which may take years, persons with post-traumatic headache may develop chronic headaches rapidly, sometimes within weeks to months after injury. Reference Cohen, Plunkett and Wilkinson8

Therefore, given the sheer volume of people who ride roller coasters in a given year and that head or neck injuries can be a risk factor for chronic headaches, understanding non-catastrophic injuries as a result of roller coaster rides is important in allowing thrill seekers to safely engage in these activities. Reference Cho and Chu9 Our study examines a group of patients with new or worsening headache or dizziness after riding a roller coaster.

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 31 adults, approved by the Stanford Internal Review Board (IRB), for demographics, medical and headache history. Participants were evaluated by the outpatient Stanford Neurology Department providers between January 1, 2015 and May 16, 2022. Clinical documentation in the medical charts was obtained by individual neurology attendings during new and follow-up patient visits from direct patient interview. Written informed consent was waived by the IRB based on the exclusion of HIPAA identifiers. Charts were requested through the secure Stanford Research Repository Tool (STARR) software with the following inclusion criteria: age equal to or greater than 18, seen between January 1, 2015 and May 16,2022, evaluated under the electronic health record context “NEURO AT HOOVER,” where the term “roller coaster” or “rollercoaster” appeared in the chart. The initial search yielded 636 charts for review, which were then deidentified. Charts were individually reviewed and excluded if they did not meet inclusion criteria or if the use of “roller coaster” or “rollercoaster” was incidental. We identified 34 participants in this search. Three additional patients were then excluded, two with recurrent seizures and one with temporary loss of consciousness after roller coasters, given the focus on headache and dizziness for this review. This is the primary analysis of these data. Missing data included the unknown ethnicities of two patients and one unknown age at the time of roller coaster ride.

Descriptive statistics were calculated within Microsoft Excel including frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation.

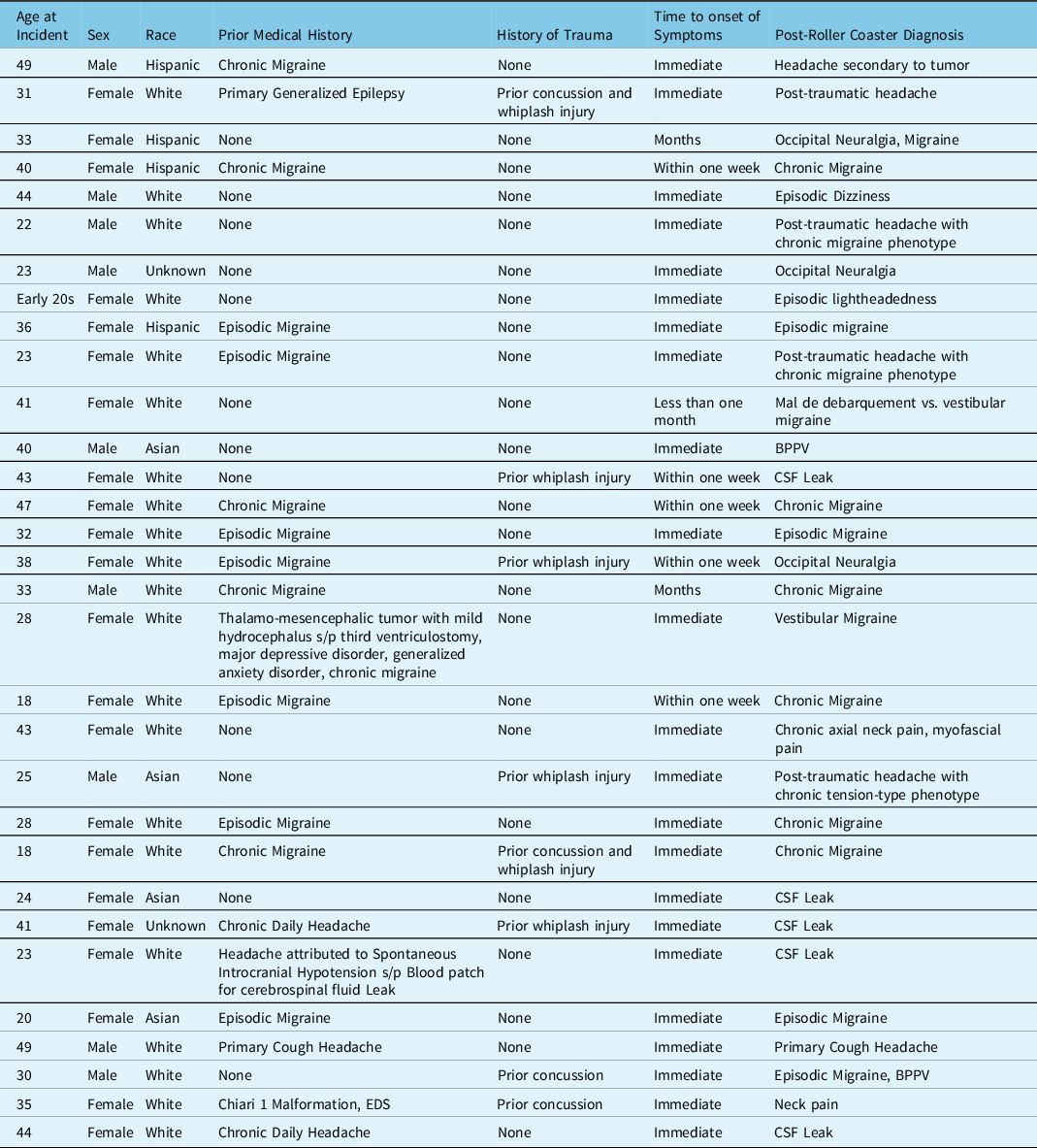

A summary of the 31 cases of new or worsening headache or dizziness after riding a roller coaster appears in Table 1. Our study population had an average age of 33.4 ± 9.4 years old and the majority were female, 22/31 (71%). Twenty-one (68%) were Caucasian and an additional four each (13%) were Asian or Hispanic with two (7%) not having a reported ethnicity.

Table 1: Summary of included cases of headache and dizziness after roller coaster rides.

An antecedent history of any headache was present in 17/31 (55%) and 13/31 (42%) had a history of migraine including either episodic migraine in 7/31 (23%) or chronic migraine in 6/31 (19%). One patient had a previous history of primary cough headache (1/31, 3%), and another patient had a history of headache attributed to spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to a cerebrospinal fluid leak that had been successfully treated with a blood patch (1/31, 3%). An additional two patients carried a diagnosis of chronic daily headache that had not been more specifically diagnosed and in whom a retrospective diagnosis could not be made with the information available in the chart. A prior history of concussion or whiplash was present in 8/31 (26%).

The primary presentations of headache after riding roller coasters included worsening headache in 11/31 (36%) and new onset headache in 8/31 (26%). Dizziness after roller coasters included new onset dizziness in 5/31 (16%) and worsening dizziness in 1/31 (3%). Two patients (7%) noted new neck pain.

Four additional patients (13%) reported roller coasters as a known exacerbating factor for their previously diagnosed migraine.

Time to onset of headache or dizziness was immediate in 23/31 (74%) and within one week in an additional five patients (5/31, 16%). Only 3/31 (10%) had onset after more than one week.

Of the 25 patients with new or worsening headache, 15/25 (60%) met ICHD-3 criteria for migraine including 8/25 (32%) who met criteria for chronic migraine. Notably, of these eight patients with chronic migraine, 4/8 (50%) previously had a diagnosis of chronic migraine, 3/8 (38%) had a history of episodic migraine, and only 1/8 (13%) had no history of migraine.

Of the 6/31 (19%) patients with new or worsening dizziness, 2/6 (33%) were diagnosed with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). The remaining four patients were reported to have episodic dizziness, and a more formal diagnosis was not made at the time and could not be made retrospectively.

Notably, 5/25 (20%) patients with new or worsening headache ultimately met ICHD-3 criteria for headache attributed to spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. Of these five patients, 2/5 (20%) had a history of chronic daily headache that was being evaluated for a more definitive diagnosis, and two others had no history of headache. One patient had a history of a CSF leak, successfully treated with a blood patch, that recurred after the roller coaster ride.

Given the large volume of people who enjoy roller coasters annually, we suspect that persistent headache and dizziness after roller coasters are relatively rare, with only 31 cases identified within the cases seen by the outpatient neurology department over seven years.

Previous reports of more severe injuries on roller coasters have attributed the damage to excessive peak G forces, a measure of acceleration; however, motor vehicle accident research has indicated that peak G forces are unlikely to cause these injuries as they are well under the maximum tolerated for humans given the brief intervals over which they are experienced. Reference Pfister, Chickola and Smith10

Certain trends in this small cohort were notable and warrant attention for specific patient demographics and future studies. Of the six patients with chronic migraine prior to riding a roller coaster, 4/6 experienced exacerbation of their migraine, one had new onset occipital neuralgia, and one had an exacerbation of their headaches which led to the discovery of a sphenoidal meningioma that was potentially contributing to their headache. It would consequently be reasonable to counsel patients with chronic migraine that roller coasters may lead to exacerbations of their headache. Additionally, roller coaster rides may not be recommended for patients with a history of CSF leak, have conditions known to predispose increased risk for CSF leak such as connective tissue diseases, or with chronic daily headaches who are being evaluated for CSF leaks. Caution may also be suggested to patients with a prior history of concussion or whiplash, as at least one of these was present in 8/31 patients.

Limitations of the study were mainly due to the location of the study and its small sample size. The San Francisco Bay Area is home to two modest sized amusement parks with notable roller coaster collections; however, neither of these is in close proximity to the Stanford Health Care Palo Alto campus. It is quite plausible that significantly more cases of new or worsening headache or dizziness would be found in studies conducted in closer proximity to those parks, or larger amusement parks hubs such as Southern California or Orlando. The number of cases seen was also likely limited by the Stanford Neurology department being a tertiary care center with a focus on complex or refractory cases and many cases may not have advanced past the patient’s primary care physician or local neurologist. Additionally, because of the small sample size and retrospective nature, the contribution of the number of roller coasters ridden or specific elements of the roller coasters such as speed, height of drops, acceleration, and inversions could not be evaluated.

Acknowledgments

We thank the providers of the Stanford Neurology Department who evaluated the patients during the study period.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

LSM and LS report no financial conflicts of interest.

Statement of Authorship

Study concept and design: LSM. Acquisition of data: LSM. Analysis and interpretation of data: LSM. Drafting of the manuscript: LSM, LS. Revising it for intellectual content: LSM, LS. Final approval of the completed manuscript: LSM, LS.