Background

The global population is aging, and it is estimated that by 2050, those over age 60 will account for 22 per cent of the total population (World Health Organization, 2021a). Supporting this aging population is a global health imperative, as identified by the World Health Organization current “UN Decade of Healthy Ageing” (World Health Organization, 2021b). An often overlooked segment of the aging population is foreign-born, or immigrant, older adults (FBOAs), particularly those who are ethno-cultural or visible minorities in the receiving countries (Karl & Torres, Reference Karl and Torres2015). Globally, this subpopulation of immigrant older adults has experienced rapid growth in the last 30 years (Guruge, Birpreet, & Samuels-Dennis, Reference Guruge, Birpreet and Samuels-Dennis2015), and will continue to grow as the population ages and people increasingly live transnational lives (Karl & Torres, Reference Karl and Torres2015).

The concurrent trends of migration and an aging population are acutely felt in Canada. In 2015, Canada achieved a historical demographic shift in which the population over the age of 65 equaled and surpassed the population of children under the age of 15 (Statistics Canada, 2015). As the population ages, there will be increased demand for health care and an increased prevalence of age-related diseases (Gougeon, Johnson, & Morse, Reference Gougeon, Johnson and Morse2017). Canada’s population is also defined by its ethnic diversity. According to the 2016 Canadian Census, approximately 7,500,000, or more than 20 per cent of the population, are foreign-born (Statistics Canada, 2016a). Older adults are even more ethnically diverse than the general population, with approximately 30 per cent having immigrated to Canada at some point in their lives (Ng, Lai, Rudner, & Orpana, Reference Ng, Lai, Rudner and Orpana2012). Since the 1970s, immigrants to Canada have come from Asia in increasing numbers (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Lai, Rudner and Orpana2012). The native language(s) of this new population is often not one of the official languages of Canada: English and French. During the 2006 census, it was found that only 12 per cent of recent immigrants’ native language was an official language of Canada; more recent census data show that nearly one quarter of Canadians speak a mother tongue that is not one of the official languages (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Lai, Rudner and Orpana2012; Statistics Canada, 2016b).

Research has demonstrated that FBOAs in Canada have a higher prevalence of chronic conditions and poorer self-reported physical and mental health than their Canadian-born peers (De Maio, Reference De Maio2010; De Maio & Kemp, Reference De Maio and Kemp2010; Dunn & Dyck, Reference Dunn and Dyck2000; Guruge, Thomson, & Seifi, Reference Guruge, Thomson and Seifi2015; Wang, Guruge, & Montana, Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019); in the Canadian context there is extensive evidence supporting the “healthy immigrant effect”, whereby immigrants, over time, experience worse health outcomes than their Canadian-born peers, even if they arrived in the country with better health (De Maio & Kemp, Reference De Maio and Kemp2010; Dunn & Dyck, Reference Dunn and Dyck2000; Guruge, Thomson, & Seifi, Reference Guruge, Thomson and Seifi2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019).

For older adults, these health disparities are caused by a range of intersecting social determinants of health, and barriers to care, including literacy, language, culture, health beliefs, and spatial and structural inequalities (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019). Complexities of family circumstances, immigration status, and the health care system further compound these challenges (Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi, & Khamisa, Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013). Patients are concerned that their family physicians fail to understand their culture and that their concerns are not being heard because of language barriers (Ahmed, Lee, Shommu, Rumana, & Turin, Reference Ahmed, Lee, Shommu, Rumana and Turin2017).

In order to improve health outcomes and the quality of health care, it is widely suggested that the essential first step is to understand how individuals are experiencing their health care (Luxford, Reference Luxford2012; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2013; Robert & Cornwell, Reference Robert and Cornwell2013). Understanding and improving the patient’s experience of care has been recognized as a key element of health system improvement; patient experience is one of the three key health care system aims recognized in Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington’s (Reference Berwick, Nolan and Whittington2008) Triple Aim framework (and also in the Quadruple Aim framework proposed by Bodenheimer & Sinsky, Reference Bodenheimer and Sinsky2014) (Berwick et al., Reference Berwick, Nolan and Whittington2008; Bodenheimer & Sinsky, Reference Bodenheimer and Sinsky2014). The links between patient experience and patient safety and clinical effectiveness have been confirmed in systematic reviews of the literature from many health care settings (Doyle, Lennox, & Bell, Reference Doyle, Lennox and Bell2013). Additionally, the care experience of older patients, many of whom have multiple chronic illnesses, is often challenged by poor health system integration and lack of communication and coordination among health care providers (Gill et al., Reference Gill, Kuluski, Jaakkimainen, Naganathan, Upshur and Wodchis2014; Lafortune, Huson, Santi, & Stolee, Reference Lafortune, Huson, Santi and Stolee2015; Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Matthew-Maich, Fraser, Dufour, McAiney and Kaasalainen2017; Toscan, Manderson, Santi, & Stolee, Reference Toscan, Manderson, Santi and Stolee2013).

There is no single operating definition of the term “patient experience” (Wolf, Niederhauser, Marshburn, & LaVeia, Reference Wolf, Niederhauser, Marshburn and LaVeia2014). We draw on the inaugural issue of the Patient Experience Journal, which posits that:

…the patient experience reflects occurrences and events that happen independently and collectively across the continuum of care. Also, it is important to move beyond results from surveys, for example those that specifically capture concepts such as ‘patient satisfaction,’ because patient experience is more than satisfaction alone. Embedded within patient experience is a focus on individualized care and tailoring of services to meet patient needs and engage them as partners in their care. Next, the patient experience is strongly tied to patients’ expectations and whether they were positively realized (beyond clinical outcomes or health status). (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Niederhauser, Marshburn and LaVeia2014, p. 3)

A framework developed by Wickramage, Vearey, Zwi, Robinson, and Knipper (Reference Wickramage, Vearey, Zwi, Robinson and Knipper2018) describes the need to understand migrant populations and their unique experiences. Particularly, the article discusses focusing on two areas to advance research: “…exploring health issues across various migrant typologies, and improving our understanding of the interactions between migration and health” (Wickramage et al., Reference Wickramage, Vearey, Zwi, Robinson and Knipper2018). The authors reason that research must be developed in both areas to truly improve the larger understanding of international migration and health (Wickramage et al., Reference Wickramage, Vearey, Zwi, Robinson and Knipper2018).

The aim of this scoping review was to understand the patient experiences of FBOAs within the Canadian health care system. Other reviews in this area of inquiry (e.g., Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019) have also employed a scoping review approach to synthesize similar literature. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no scoping or systematic review of the patient experiences of FBOAs in Canada to date, although several authors have synthesized the barriers that immigrants (e.g., Kalich, Heinemann, & Ghahari, Reference Kalich, Heinemann and Ghahari2016), and older immigrants specifically (Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013; Lin, Reference Lin2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019) face when accessing care in Canada. It is well established that older adults confront unique challenges in navigating and interfacing with the Canadian health care system (Drouin, Walker, McNeil, Elliott, & Stolee, Reference Drouin, Walker, McNeil, Elliott and Stolee2015; Stolee, MacNeil, Elliott, Tong, & Kernoghan, Reference Stolee, MacNeil, Elliott, Tong and Kernoghan2020). Prior scoping reviews have consistently identified barriers to care for immigrants and FBOAs, including language barriers, barriers to information, cultural differences, and intersecting barriers related to gender, culture, and power structures experienced by immigrants (Kalich et al., Reference Kalich, Heinemann and Ghahari2016; Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013; Lin, Reference Lin2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019). What has not yet been reviewed are the patient experiences and patient engagement of FBOAs when receiving care. This review will explore the gap in this literature.

Methods

This review was completed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews, and followed the steps outlined in Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun and Levac2018). In performing this review, we sought to answer the question “What is known about patient experience of foreign-born older adults (60 years and older) residing in Canada?” Studies performed in English and French were included in the review, reflecting the national languages of Canada (McCullough, Reference McCullough2020). There were no restrictions on the year of publication.

Type of Participants

FBOAs of both sexes 60 years of age and older residing in Canada were included for review (Statistics Canada, 2020). The age criterion of 60 years and older was chosen to reflect the World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition of an older adult (World Health Organization, 2002). Participants arriving through all immigration streams (e.g., economic, family, refugee) were eligible for inclusion. We did not filter or search for specific ethnicities, or limit it by visible minority/racialized status.

Type of Studies

We included any studies performed in a health care setting that were published in a peer-reviewed journal. All forms of original research were eligible (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed-method, interventions). Health care settings for review were defined as settings where care, either preventive or curative, are provided, including: acute-care hospitals, long-term care facilities, primary care settings, urgent-care centers, outpatient clinics, home health care, and emergency medical services (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Patients whose primary focus was accessing mental health services were excluded, as this topic warrants its own study and has been reviewed in detail by Guruge, Thomson, & Seifi (Reference Guruge, Thomson and Seifi2015). Interactions with the health care system for cosmetic surgery, dental care, optometry, and alternative medicine were also excluded.

Type of Outcomes

The outcome of interest for this study was the patient experience of FBOAs in a Canadian health care setting. For this study, patient experience could include both self-reported experiences and/or a credible source reflecting on the patient experiences of FBOAs (e.g., family caregivers or primary care providers summarizing experiences).

Search Strategy

The selection of electronic databases and the search strategy were developed in conjunction with an information specialist librarian at the University of Waterloo. The following databases were searched regardless of year of publication to August 2020:

-

• MEDLINE® (via Ovid, 1946 to present)

-

• Excerpta Medica Database (Embase) (via Ovid, 1974 to present)

-

• Web of Science Core Collection (1976 to present)

-

• Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO Host, 1981 to present)

-

• Cochrane Central Library (via Cochrane Library, 1948 to present)

-

• Sociological Abstracts

Search Terms

To identify appropriate key words, in addition to medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, commonly used wording and phrases stated in related literature were utilized. The search strategy was first developed and run in MEDLINE; we then applied the same search strategy to the remaining databases.

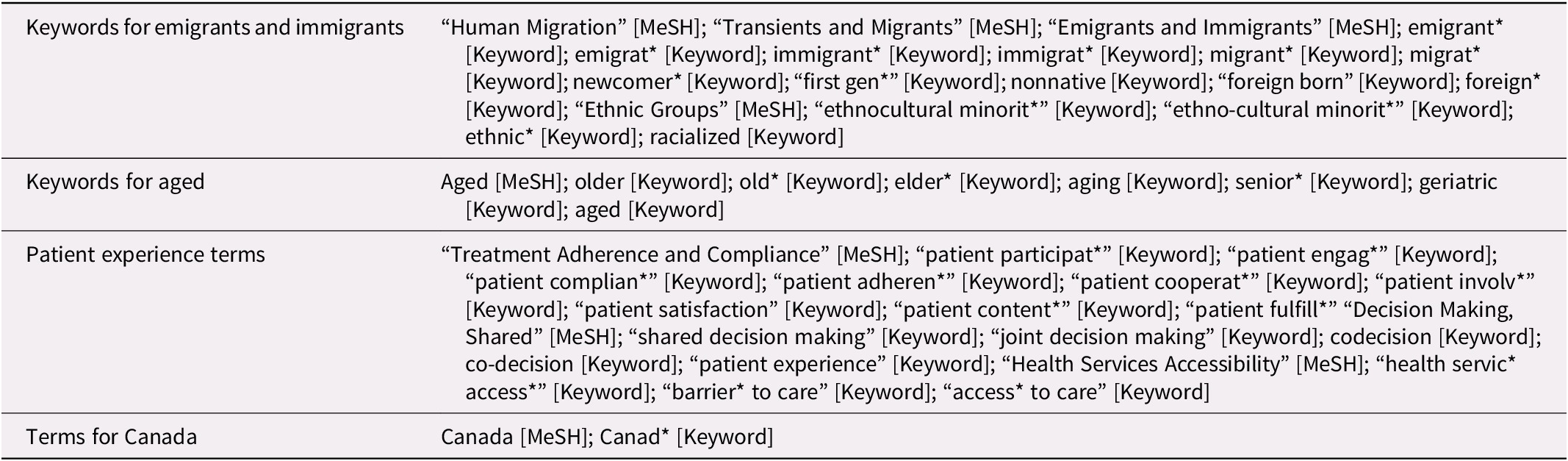

Keywords used for the study were related to Canadian ethnocultural minority older adults, foreign-born older adults, and their experiences with the health care system. We used terms related to ethnocultural minority older adults, in addition to foreign-born/immigration status, as many studies use keywords related to ethnicity, but not always to migration status. The keywords were combined using the Boolean operators OR and AND. The initial search strategy for MEDLINE is included in Table 1. Keywords and search terms were reviewed by a senior member in the team and a health sciences librarian, to add rigour to generated results.

Table 1. Medline search terms

Study Selection

After running searches through each database and removing duplicates, one reviewer screened titles and abstracts of studies to select potentially relevant studies. Once this was completed, the same reviewer then obtained and reviewed the full texts of the potentially relevant literature to include in the final analysis. This was a student lead review, with one student, the lead author, conducting the scoping review. The study selection process was aided with the use of Covidence review software (Veritas Health Innovation, n.d.). Senior members of the research team also reviewed the screening completed in Covidence, and the first and last authors, JW & CT, reviewed instances in which inclusion/exclusion was not clear.

Data Extraction

The same reviewer who completed the study selection also performed the data extraction. All co-authors created the data extraction template, which included: publication details (author(s), publication year, journal title), study design and methods (aim of study, inclusion and exclusion criteria of study participants, recruitment, analyses, limitations, underlying theory), participant characteristics (number of participants, age, sex, ethnicity, country of origin), details regarding focus of the study (e.g., intervention if there was an intervention, observations or specific population groups), outcomes/findings, and implications for the immigrant experience. Data were synthesized for presentation in this review and included: author(s), year, type of study, study objectives, study population, province, age, and key findings relevant to the research question guiding this review.

Data Synthesis

For this review, the province, type of study, type of intervention, population (age, background, gender, and health conditions) and key findings are synthesized and presented in a narrative format.

Results

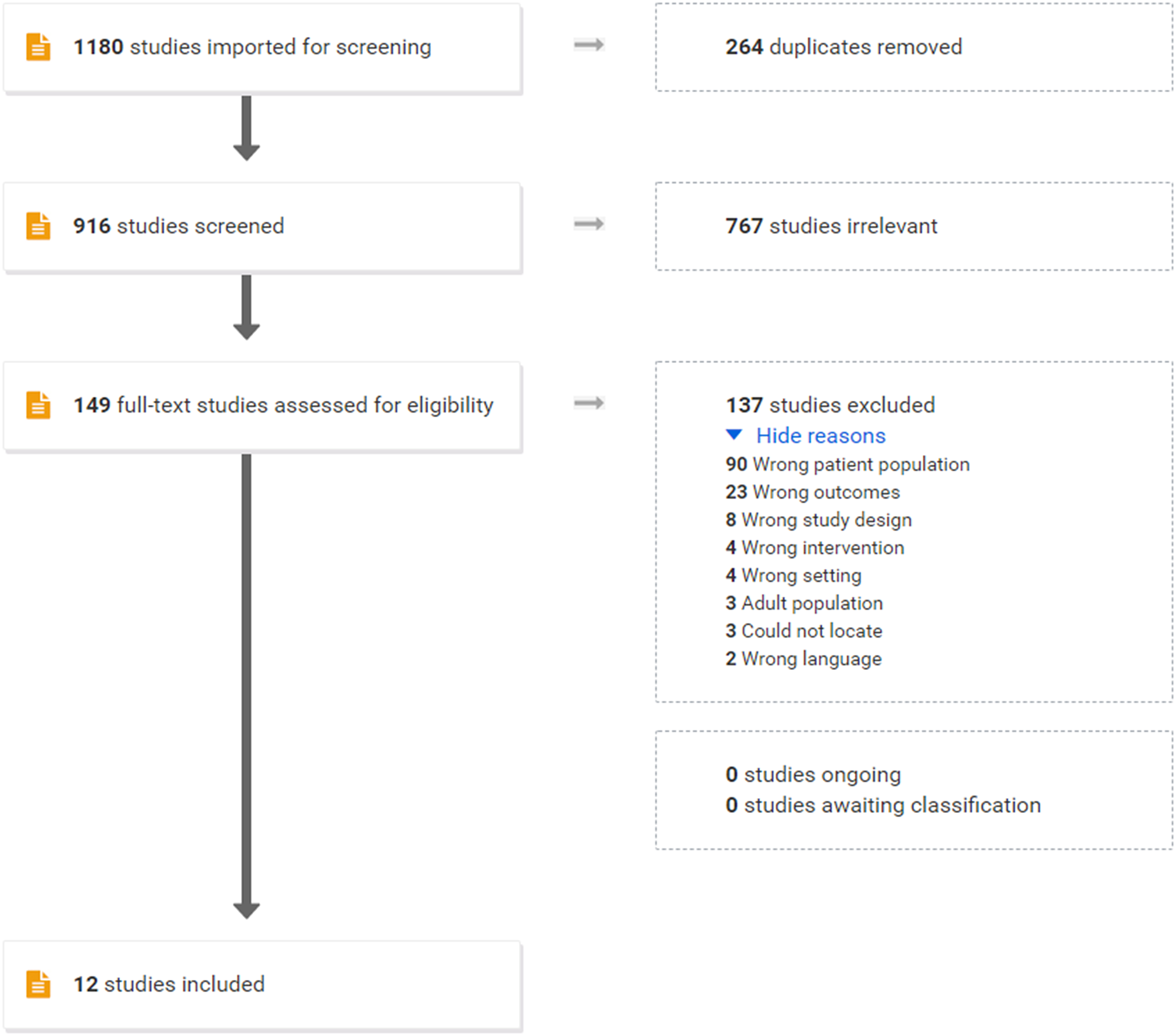

Once duplicates were removed from the initial searches, the reviewer had 916 articles to review at the title and abstract level. The reviewer then completed a full text-review of the 149 articles to ascertain relevance to the research question. Through the full-text review, we obtained 12 articles that were within the scope of this review and addressed the research question. Articles were then reviewed with a senior member on the team to add rigour to the results. The flow chart for study selection is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study selection flow chart.

Study Characteristics

A range of study populations was assessed in the selected articles. Most study populations (9 of 12) were located in 3 of the 10 Canadian provinces and territories (Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario). One study did not state its location and two studies were performed in multiple cities (King, LeBlanc, Sanguins, & Mather, Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a, Reference Lai and Chaub). There were no studies for the provinces of Saskatchewan, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, or the Territories.

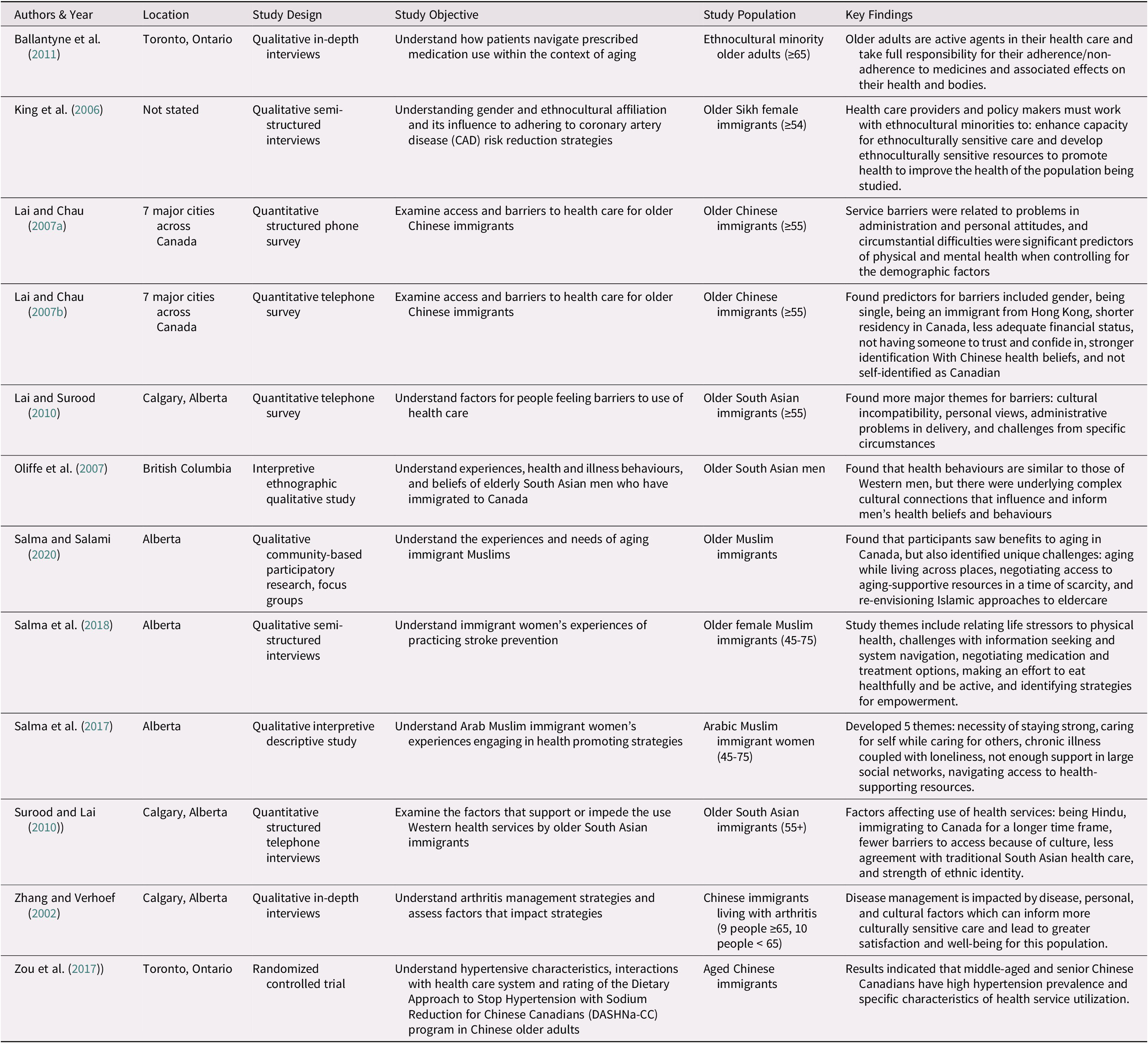

All studies that were included in this synthesis recruited FBOAs in Canada. Most of these participants had relocated to Canada from India and China. Three studies examined the experiences of South Asian FBOAs and four focused on Chinese (Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a, Reference Lai and Chaub; Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010; Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke, & Toor, Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Surood & Lai, Reference Surood and Lai2010; Zhang & Verhoef, Reference Zhang and Verhoef2002; Zou, Dennis, Lee, & Parry, Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017). Three articles examined the experiences of Muslim FBOAs and one article examined Sikh immigrants’ experiences (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie, & Keating, Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Salma, Keating, Ogilvie, & Hunter, Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020). Only one article examined FBOAs from a range of ethnic groups, and no studies examined the patient experiences of FBOAs who were from European or English-speaking countries of origin, such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia, (Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon, & Fisher, Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011). More information regarding the context of the populations reviewed can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of articles

Four studies focused on the barriers faced by specific genders. One study focused exclusively on older South Asian men’s experiences with health care, and three studies focused specifically on the experiences of women (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017, Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). The remaining eight included both men and women.

Seven of the 12 studies were qualitative, and the remaining 5 were mixed-methods or quantitative (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011; King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a, b; Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017, Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020; Surood & Lai, Reference Surood and Lai2010; Zhang & Verhoef, Reference Zhang and Verhoef2002; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017). None of the studies included the perspectives of health care providers or family members of the FBOAs; all were specifically about FBOAs’ first-hand experiences. For more information and summaries of each study, please see Table 2.

Synthesis of Studies

Many FBOAs emphasized that they appreciate the universal health care system in Canada, and that it allowed them to access care more freely than in their countries of origin (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020). However, there were also multiple barriers that prevented them from accessing care when or how they needed it. In our analysis, the discussion of patient experience was largely related to barriers to care. We have organized these barriers into five categories: communication barriers, lack of cultural integration in Canada, structural hurdles within the health care system, inadequate financial support, and intersecting barriers related to culture and gender. It is of note that studies generally emphasized areas for improvement, and there were limited discussions of patient experiences that were neutral or positive in nature.

Barriers

Communication

Effective communication is essential when providing or receiving health care. In these articles, however, it was evident that there have been gaps in communication and understanding for Canadian FBOAs trying to access health care services.

It was widely discussed that FBOAs faced significant challenges in communicating with their health care providers (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011; Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a, b; Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010). Each article discussed that FBOAs are daunted by the task of trying to understand and communicate their health care needs in the English language when it is not their native language. Although the majority could communicate in English (to varying degrees), many participants found it hard to understand and communicate health care needs to a physician. Patients would obtain an interpreter (often a family member) to ensure that they could understand and would be properly understood by their physician. Others would specifically find physicians who could speak their primary language. One study found that if patients could not find a physician who spoke their language, they would avoid seeking care, even if they had health conditions that needed attention (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007). Communication barriers meant that FBOA patients would not fully communicate their health concerns and would often not understand the instructions that their health care provider was giving (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006).

Another communication-related finding was that FBOAs are often unclear about the structure of the Canadian health care system. Canada’s universal health care system covers many, but not all, health-related expenses, such as medications or alternative therapies. Diagnostics not deemed mandatory may also require a fee (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020). Across these 12 studies, it was evident that many FBOAs did not fully understand what was covered under Canada’s health care system and what was not (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020). This resulted in tension with health care providers and lack of adherence to medical advice. One study found that participants believed that physicians would prescribe medications out of greed, assuming that they were receiving compensation from pharmaceutical companies (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007).

Lack of cultural integration in the Canadian health care system

As noted, the Canadian health care system currently does not cover many alternative therapies, although some individuals may have private insurance benefits to cover chiropractic care, acupuncture, massage therapy, and homeopathy (McFarland, Bigelow, Zani, Newsome, & Kaplan, Reference McFarland, Bigelow, Zani, Newsome and Kaplan2002). Treatments such as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and natural remedies are often an out-of-pocket expense (McFarland et al., Reference McFarland, Bigelow, Zani, Newsome and Kaplan2002). Many studies found this to be highly influential in determining how often FBOAs followed through with advice from health care providers. Participants believed that Western medicine is one, but not necessarily the best, option, and that treatments such as TCM should be explored in conjunction with or before Western medicine (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011). Also deterred by the cost of prescription medications, many would seek alternative medicines rather than go to the formal Canadian health care system for treatment (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011; Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a, b; McFarland et al., Reference McFarland, Bigelow, Zani, Newsome and Kaplan2002).

Two studies found that lifestyle instructions and guidance did not take into consideration FBOAs’ cultural context (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017). These studies found that although many FBOA participants wanted to improve their health, they often did not know how to take the instructions they were given and apply these to their own lives. For example, nutrition plans are often designed around a traditional Western diet, but participants did not know how to apply the guidance received to their non-Western diets (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017). Because of this barrier, many disregarded dietary information altogether (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017).

Structural hurdles within the health care system

Patient complaints regarding long wait times are common in Canada, and this was also true for FBOAs in the studies reviewed (Lafortune et al., Reference Lafortune, Huson, Santi and Stolee2015). Five of the 12 reviewed articles cited long wait times as a significant barrier to accessing the Canadian health care system (Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a; Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020; Surood & Lai, Reference Surood and Lai2010). These wait lists sometimes resulted in individuals losing trust in the Canadian health care system or turning to other avenues to gain the care that they needed. One study found that participants would return to their home countries and pay for surgeries and procedures rather than wait (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007).

Specific to older adults, it is well-documented that it can be challenging for patients to manage multiple chronic conditions when many Canadian health care providers limit appointments to short time frames and “one issue per appointment” (Clarke, Bennett, & Korotchenko, Reference Clarke, Bennett and Korotchenko2014). In Zhang and Verhoef’s study (Reference Zhang and Verhoef2002), participants reported feeling disinclined to access the health care system because of the limited time they were able to spend with their health care provider. Short appointment times for FBOAs also meant that they would rush through explaining their health issues and not ask questions if they did not understand (Zhang & Verhoef, Reference Zhang and Verhoef2002).

Inadequate financial support

Although Canada has a comprehensive health care system that does not require residents to pay out of pocket for many essential health care services (e.g., primary care visits, hospital stays), certain services such as prescriptions are not covered (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Mirza, Austin, Boon and Fisher2011; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Dennis, Lee and Parry2017). This has created a financial barrier and has also deterred some from seeking care. In response to this barrier, some participants obtain prescription medications from overseas (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007) or ration their medications to last longer (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017).

Participants across the studies also cited an overdependence on informal support networks (e.g., family and friends) as a barrier to care (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Lai & Chau, Reference Lai and Chau2007a; Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020; Surood & Lai, Reference Surood and Lai2010). Many FBOAs were hesitant to access health care for fear of burdening their families (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006). Some studies discussed how FBOAs must rely on family and friends for transportation but do not wish to trouble them, causing them to forego accessing health care (Lai & Surood, Reference Lai and Surood2010; Salma & Salami, Reference Salma and Salami2020). Other participants discussed wanting to be able to afford certain things like a healthy diet or exercise equipment, but pension incomes, both Canadian and/or international, were not sufficient to cover such expenses (Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018; Surood & Lai, Reference Surood and Lai2010).

Intersecting barriers related to culture and gender

The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity states that, “culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs” (UNESCO, 2006). Culture has the capacity to impact key aspects of an individual’s life and is an important consideration when understanding health. Cultural barriers were a common theme throughout the literature and frequently intersected with issues related to gender.

FBOAs had definitions of health and well-being that were distinct from those in a Western health care system (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). With different backgrounds and cultures come different definitions of one’s own health. For example, one study looking at older female Muslim immigrants found that the participants generally believed that their physical health was dictated by the life stressors that they were experiencing (Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). They described their health as being a result of great pains they had suffered (like taking care of a dying parent) and they believed that they might not have gotten sick if they had not experienced those hardships. They did not interpret their health as being a result of the progression of diseases that they had (Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). Another study looking at the experience of older South Asian men found that many of the participants believed that the deterioration of their health was almost exclusively tied to a lack of physical activity in older age, especially when contrasted with the physical demands of their youth (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007). This view of health did not capture other personal habits (e.g., smoking, diet) and biological factors that may predispose them to certain types of illnesses. Salma et al. (Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018) also found that participants did not understand the importance of preventive prescriptions and believed that an over-reliance on medications would do the body more harm than good; consequently, participants would periodically stop taking medication to “give their bodies a rest” (Salma et al., Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018).

Oliffe et al. (Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007) found that older South Asian men face unique barriers when accessing health care. The study found that the participants believed that their illnesses had to be life threatening before they thought it would be suitable to access health care (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007). The authors hypothesized that this was probably because in their countries of origin, participants had to pay out of pocket and travel significant distances to access health care. These participants therefore limited seeking health care to scenarios in which they perceived it to be urgent or necessary (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007).

Women also faced unique challenges when accessing health care. In multiple studies, research found that women felt obliged to put the needs of family members before their own, especially in times of family crisis (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017, Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). Another challenge that women faced was that many would rely on their husbands to make health care decisions for them, as this was understood to be a cultural norm (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006).

Limitations of the Studies Included

The studies included in this review, both individually and collectively, have limitations. First, there was limited primary research available in this field, meaning that some voices were more strongly represented in the literature; however, those voices may not represent the broader experiences of FBOAs. Indeed, most studies focused on the experiences of Chinese and South Asian older adults in Canada. This does not accurately reflect the diversity of older adults in Canada. From 2006 to 2011, the top 10 countries of origin for immigrants were the Philippines, China, India, the United States, Pakistan, the United Kingdom, Iran, South Korea, Colombia, and Mexico (Statistics Canada, 2011). The present literature does not reflect the current diversity in Canada and does not consider the immigrant experiences of non-racialized older adults (e.g., those who are white, but may not speak English or French). Some ethnocultural communities have not been considered in this body of literature, and the results presented here represent only a portion of all FBOAs’ experiences with the Canadian health care system. It is difficult to predict how the findings of this review might have been affected had there been greater diversity in the study populations reflected in available studies. The studies also fail to reflect geographic diversity, with most of the work concentrated in 3 of the 10 provinces, with data collection largely focused on urban areas. This is not likely to affect the outcomes of the study in a significant way. In 2018, 91 per cent of immigrants and refugees lived in Canada’s largest metropolitan centres (Government of Canada, 2018). The sum of literature available is not an accurate representation of the experiences of all FBOAs, and in fact only represents a small portion of FBOAs in Canada.

Discussion

Under the Canada Health Act, all Canadians, regardless of age or ethnicity, have access to health care without financial or other barriers (Government of Canada, 2020). Our review, however, has demonstrated that FBOAs are confronted with several barriers in accessing care, including communication barriers, lack of cultural integration in Canada, structural hurdles within the health care system, inadequate financial support, and intersecting barriers related to culture and gender. It is of note that studies generally emphasized areas for improvement, and there were limited discussions of patient experiences that were neutral or positive in nature. Although we sought to understand the patient experience of FBOAs (using search terms such as patient experience, patient engagement and patient activation), consistent to prior reviews, the studies that we found also emphasized barriers to care (Kalich et al., Reference Kalich, Heinemann and Ghahari2016; Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013; Lin, Reference Lin2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019). This highlights a gap in the available literature and emphasizes a need for further exploration of patient experience for FBOAs; as we know, understanding patient experience and engagement, in order to intervene as needed, has the potential to improve the quality and outcomes of health care (Luxford, Reference Luxford2012; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2013; Robert & Cornwell, Reference Robert and Cornwell2013). In many instances there is limited commentary on the patient experience, because participants across the studies are not accessing the health care system. This limited access (Luxford, Reference Luxford2012; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2013; Robert & Cornwell, Reference Robert and Cornwell2013) may limit knowledge on where and how the health care system is (or is not) meeting the needs of FBOAs. Further exploration of patient experience amongst FBOAs may also identify areas where improvements and interventions should be made. The impact of these barriers is compounded by the fact that FBOAs are more vulnerable to negative health transitions and poorer health status than their Canadian-born older adult peers and than younger cohorts of immigrants (Dunn & Dyck, Reference Dunn and Dyck2000; Guruge, Birpreet, & Samuels-Dennis, Reference Guruge, Birpreet and Samuels-Dennis2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019).

Implications for Research

To date, there is limited research specific to the patient experience of FBOAs. Our review is situated within a larger (but still limited) body of research examining foreign-born experience with the Canadian health care system, for immigrants of all ages (e.g., Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Shommu, Rumana, Barron, Wicklum and Turin2016; Kalich et al., Reference Kalich, Heinemann and Ghahari2016; Vang, Sigouin, Flenon, & Gagnon, Reference Vang, Sigouin, Flenon and Gagnon2016). Our review examined the patient experience and barriers specific to the older cohort of the immigration population, although it is important to note that the studies overwhelmingly focused on barriers, and not necessarily on patient experience.

Our findings are consistent with other research in this area: similarly to Wang et al.’s (Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019) review of older immigrants’ experiences with primary care, we too identified the importance of language and culture (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019); we also echo the findings of Khan and Kobayashi (Reference Khan and Kobayashi2015) in their analysis of health promotion uptake by older immigrants, who also emphasized the importance of system navigation and how diverse life experiences may influence when and how an FBOA accesses and experiences the health care system (Khan & Kobayashi, Reference Khan and Kobayashi2015).

Although this was briefly touched on in our review, future research should aim to address gaps in understanding gender roles for FBOAs, and how evolving cultural norms and life course experiences may impact older immigrants’ ability to access and receive care (Torres, Reference Torres2015). In an increasingly transnational world, additional insights would also be gained by engaging in an international review of older immigrants’ patient experiences, particularly the experiences of those who may be racialized or marginalized in their receiving country. More research into these areas would benefit these smaller and more vulnerable subsets of the population as well as paving the way for more equitable practices and policies. Sexual orientation and gender identity were not considered in the studies included in this review, and this merits future research

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Applied Research

This review serves as a reminder to health care practitioners, who are serving a growing and increasingly diverse patient population, that the FBOA patients they are serving arrive with a range of needs, far beyond the most obvious one of communication (see also Kalich et al., Reference Kalich, Heinemann and Ghahari2016). It is often suggested that a translator, translating family member/caregiver, and/or translated resources are sufficient to fill the gaps for immigrants engaging with the health care system. Our review reaffirms that this is not the case; FBOAs also require supports with system navigation, culturally competent resources, a more comprehensive basket of resources, and providers who understand how cultural and gendered norms can impact one’s ability or willingness to receive care (King et al., Reference King, LeBlanc, Sanguins and Mather2006; Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Grewal, Bottoroff, Luke and Toor2007; Salma et al., Reference Salma, Keating, Ogilvie and Hunter2017, Reference Salma, Hunter, Ogilvie and Keating2018). Future initiatives with FBOAs should not only discuss barriers to care, but should also endeavor to co-create mechanisms and solutions (e.g., co-designed resources drawing on the lived experience of FBOAs and care providers), to support patient experience in this population. In a post-COVID-19 era, with the explosion and greater acceptance of virtual care and online/remote modes of medical interpretation, there is also an opportunity to examine the potential, pitfalls, and appropriateness of virtual care and online/remote medical interpretation for FBOAs. We intend to pursue some of these aims in our future work.

Finally, we would add that this is not something that one health care provider can provide. Supporting the patient experience of FBOAs and meeting the health care needs of these older adults requires a community-oriented public health approach (Gómez-Batiste et al., Reference Gómez-Batiste, Martínez-Muñoz, Blay, Espinosa, Contel and Ledesma2012). Truly addressing the barriers that our review has identified will require input and investments from the broader community of service providers (e.g., social workers, pharmacists, translators, allied health professional), all levels of government, and community organizations (e.g., cultural groups, religious communities, and non-profit organizations).

Finally, we note that many of the barriers to care identified in our review are not specific to immigrants; it is well documented in Canadian gerontological and health services research that older adults of all ethnicities and countries of origin are grappling with issues related to long wait times, short “one issue” health care appointments; navigating complex and disjointed health care systems; limited coverage of health care expenses for items such as prescription drugs, hearing aids, and prescription eyewear; and insufficient home- and community-based care (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Bennett and Korotchenko2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Bacsu, Abeykoon, McIntosh, Jeffery and Novik2018; Lafortune et al., Reference Lafortune, Huson, Santi and Stolee2015; Morgan & Boothe, Reference Morgan and Boothe2016; Stolee et al., Reference Stolee, MacNeil, Elliott, Tong and Kernoghan2020). Improving care for older adults is an area of national concern, and one for which several Canadian advocacy and professional organizations are advocating (e.g., Armstrong & Cohen, Reference Armstrong and Cohen2020; Canadian Home Care Association, 2016; Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Our review demonstrates that in addition to the issues outlined, FBOAs’ patient experiences are further compounded by intersecting statuses of gender, culture, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and others (Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi and Khamisa2013; Lin, Reference Lin2021). In our failure to meet the needs of all older Canadians, we have further marginalized the health care of those who are especially vulnerable.

Limitations to this Review

One reviewer was used to select the research articles included. This may mean that the studies selected reflect the unique lens of the one reviewer rather than a more rigorous review by two reviewers.

Conclusion

This scoping review has demonstrated that the topic of FBOAs’ experiences with the Canadian health care system is particularly under-studied, with only 12 original research articles retrieved, none of which explicitly focused on patient experience, which was the aim of our research question and search terms. This suggests that very little is known about the patient experiences of FBOAs in receipt of care. Consistent with prior reviews, multiple themes were identified as barriers for FBOAs, including communication barriers, lack of cultural integration, structural hurdles within the health care system, inadequate financial support, and intersecting barriers related to culture and gender. Many sizeable and growing ethnic populations are also overlooked.

The findings of this review have the potential to inform policy makers and providers about avenues to improve patient experience in FBOAs and reduce the barriers that they face. We also note the need to move beyond descriptive studies, and toward action-oriented studies, such as intervention studies to improve the patient experience of FBOAs, and participatory action research with ethnocultural and immigrant communities to address the well-documented barriers. Policy implications of the findings include expanding formal supports available to FBOAs to meet unmet health care needs and reduce the burden on these individuals’ informal support systems and integrating alternative medicines to improve culturally relevant care.

Aligned with the Canadian Health Act, which assures equitable health care for all, it is both a practical and moral imperative to invest in the health of all Canadians, particularly those who are confronted with multiple barriers to accessing care (Canadian Home Care Association, 2016). Promoting the health of all individuals, including that of FBOAs, will assure a more inclusive and well nation for years to come.