No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

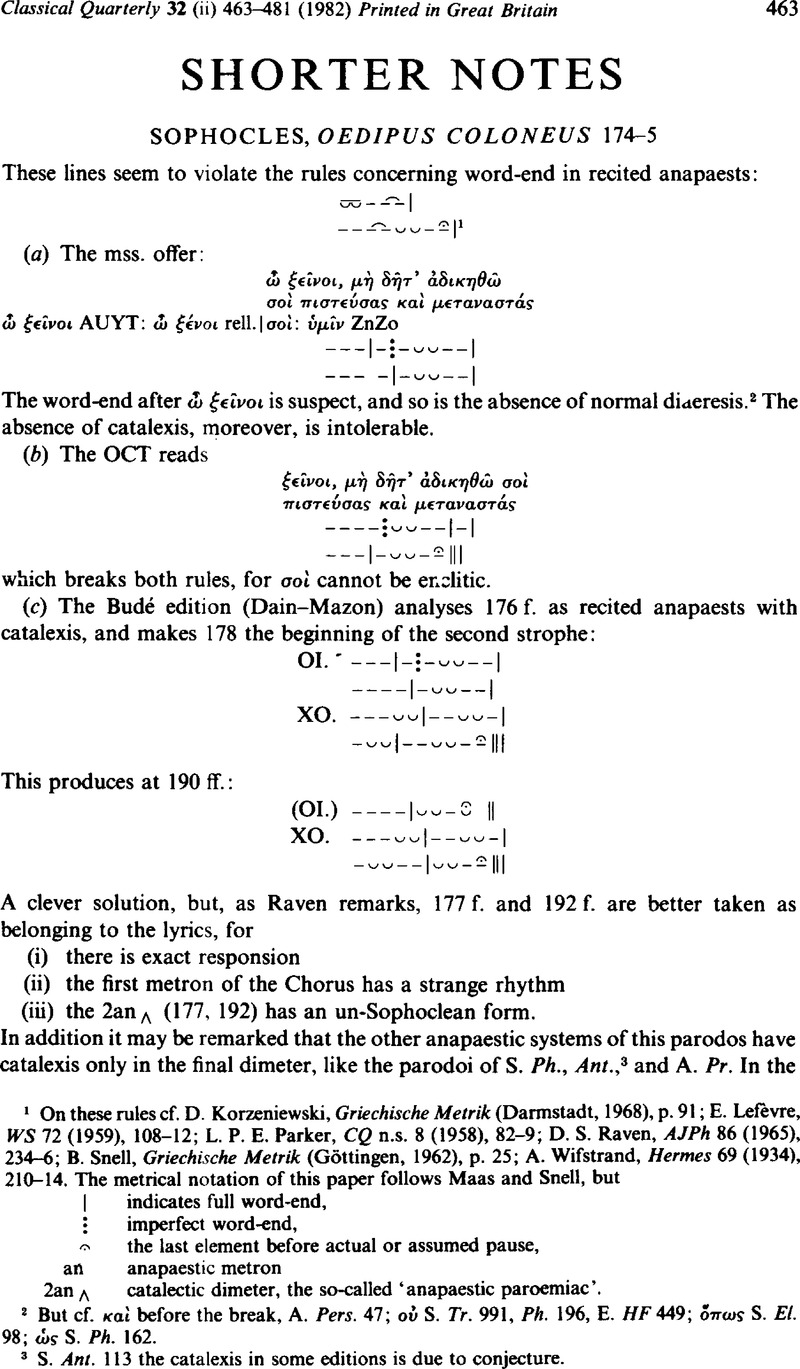

1 On these rules cf. Korzeniewski, D., Griechische Metrik (Darmstadt, 1968), p. 91;Google Scholar E. Lefevre, WS 72 (1959), 108–12; L. P. E. Parker, CQ n.s. 8 (1958), 82–9; D. S. Raven, AJPh 86 (1965), 234–6; Snell, B., Griechische Metrik (Göttingen, 1962), p. 25;Google ScholarWifstrand, A., Hermes 69 (1934), 210–14. The metrical notation of this paper follows Maas and Snell, butGoogle Scholar

2 But cf. κα⋯ before the break, A. Pers. 47; οὐ S. Tr. 991, Ph. 196, E. HF 449; ὅπως S. El. 98; ως S. Ph. 162.

3 S. Ant. 113 the catalexis in some editions is due to conjecture.

4 S. OC 188, hiatus without change of speaker, but with rhetorical pause, should not be emended. The same may be true of A. Pers. 18, but there is no justification for the phenomenon in S. Aj. 169. A. Ag. 794 f. has a lacuna. A. Ag. 1537 ἰὠ λ*** λ*** is exclamatory, therefore no example, since hiatus after exclamations is admissible everywhere. E. Hipp. 1377, Hec. 83, Ion 167, IT 125, 147, 231 are sung. Cf. this catalogue with Korzeniewski, p. 89. E. Or. 1302, Fr. 773. 68, and perhaps Supp. 277 are comparable dactylic examples.

5 S. Ph. 161 ἄπεστι QR is therefore metrically possible.

6 Fraenkel's reservation, RhM 72 (1917/18), 186 n. 1, seems not justified in view of the anapaestic parallels.

7 S. El. 88 f., 105 f., E. Ion 859–61 are by no means comparable, as those long anapaestic passages are not interrupted by lyrics.

8 cf. Wilamowitz, Griechische Verskunst, p. 348 n. 2.